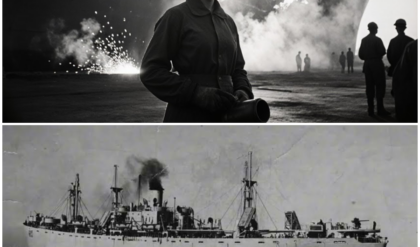

They expected junk. American shortcuts, disposable war machines built too fast to matter. But when German engineers pulled apart a captured Sherman, they didn’t find cheap shortcuts or sloppy welds, they found something worse. A secret Americans had built quietly. not to win the first battle, but to survive everyone after it.

And in that moment, Germany realized the war wasn’t just about guns and armor. It was about something far more dangerous. How fast America could build an army from scratch. The Sherman sat in a courtyard behind a captured repair depot. Its olive drab paint scarred by shrapnel, mud, and thyme. Not destroyed, not burned out, just stalled.

The German soldiers had dragged it there days earlier after an ambush caught an American armored column along a narrow road. Three American tanks burned. One didn’t. This one. The Germans expected minimal resistance inside the disabled machine, but they found something odd. Every crew member had bailed out alive.

A working tank abandoned voluntarily. It made no sense. They sent for a technical team, a mix of engineers, machinists, and students from an armament school. Not elite soldiers, not frontline heroes. Men with notebooks, pencils, and curiosity. The kind of men who believed wars were one with precision, not noise.

They studied German machines as if they were architecture. Beautiful, balanced, complex, demanding. To them, the Tiger wasn’t just a weapon. It was a sculpture with tracks. And now they stood in front of a Sherman, a tank their officers mocked as crude, cheap, mass-roduced garbage. One student muttered, “If it is a mannequin, it must be badly made.

” The lead engineer didn’t answer. They took notes. The welds were not elegant. The armor plates were not perfect. The angles were simple. Everything looked ordinary, not refined, not masterful, not German. One of the students smirked. It looks like they built it in a factory that makes stoves, another added. Or refrigerators, they laughed quietly.

But the older engineer didn’t. He saw something else. He saw design choices, deliberate, not lazy. He noted common bolt sizes, standardized access points, modular segments, easy removal panels, he whispered almost impressed, “This is not built to be perfect. This is” The engine compartment was secured with clamps and bolts.

Nothing exotic, nothing artistic, nothing German. Two men loosened the fasteners and swung the rear panels open. The smell hit instantly. Oil, fuel, metal, and long miles. Inside was not a masterpiece. Not a complex power plant with delicate tolerances. It was a radial engine like an aircraft engine, but adapted for a tank.

Simple, rugged, ugly, but powerful. One student gasped. They use aircraft engines. Another replied, confused. Why would anyone do that? The lead engineer nodded. Because they already build engines for airplanes and they can build thousands. A tank built from aviation parts to Germans who engineered custom components.

They expected to find cracks, warping, misalignment, signs of stress. They didn’t. Everything inside the Sherman looked serviceable, dirty, but functional. Worn, but not failing. The lead engineer ran a finger along a connecting rod and frowned. This didn’t break. It simply wore down. A student shrugged.

And why did they abandon it? The engineer smiled so they could fix it later. The students blinked. Fix it out here. He tapped the engine block lightly. A student wrote in his notebook, frustrated. It is not refined. It is lazy. The engineer shook his head. Not lazy. Practical. Germany built tanks like watches, precise, complex, delicate, beautiful.

America built tanks like tools, cheap, fast, repeatable, forgettable. The student asked, “But why would anyone want a forgettable tank?” The engineer looked him dead in the eyes. They pulled off ancillary components, expecting chaos. Instead, they found universal part codes, matching bolts, identical fittings, labeled wires.

The engineer froze. This is standardized. Standardization was the holy grail of manufacturing, the ability to mass-roduce reliable, identical components at industrial scale. Germany didn’t have it. They had craftsmanship, not uniformity. The engineer whispered, “They can build 10 engines while we build one.” A student interrupted.

“But ours is better.” The engineer by noon, the courtyard was silent. No jokes, no mocking, just mechanical inspection and the uncomfortable truth building in their minds. America had not beaten Germany with superior tanks. They had beaten Germany with superior logistics. A system that could build faster, ship faster, repair faster, supply faster.

A system Germany couldn’t match. The Sherman wasn’t a masterpiece. It didn’t need to be. It just needed to exist in overwhelming quantity tomorrow and the next day and the one after that. The engineers stepped away from the engine. By late afternoon, the courtyard had turned into a workshop. Tools scattered, panels removed, pencils worn dull.

The engineers weren’t laughing anymore. A young technician named Olrich finally snapped. This is ridiculous. Just because they build more doesn’t mean they build better. A senior machinist shook his head slowly. War does not ask for better. War asks for enough. Olrich slammed his notebook shut. Then why do we spend months designing the perfect tank? The older man stared at the Sherman’s open engine bay. Because we built for victory.

They built for exhaust. They inspected deeper. Carburetors, cooling lines, ignition harnesses, everything was accessible. Not elegant, not hidden behind armor or sealed compartments. One technician frowned. It is as if they want soldiers to fix it. The engineer nodded. They do. Another scoffed. Our tanks can only be repaired by specialists.

The engineer took a long breath. which is why so many of ours are left to rot when they break. Silence. It wasn’t that German tanks were weak. They weren’t. The Tiger could kill anything. The Panther was a masterpiece. But both had a flaw. One of the students found a folded maintenance card wedged behind a radio mount.

A small checklist covered in grease. He read it aloud. Daily inspection. oil level, water level, spark plugs, belts, cooling fan. He frowned. This looks like aircraft maintenance. The engineer nodded. It is. Another asked. Simple enough for soldiers? Yes. Fast enough for war? Yes. They stared at the card. something so unassuming, so basic.

By now, most engineers were convinced, but one man refused. His name was Krueger, an ambitious, fiercely nationalistic mechanical officer. He had arrived late, wearing a spotless uniform, expecting to deliver criticism, not learn anything. He scalled, “Our tanks are superior. This is trash.” The lead engineer didn’t argue.

He simply pointed around the courtyard. Three destroyed American tanks burned to skeletons, but dozens more were already reported moving again on neighboring roads. Krueger held his ground. They tooured deeper into the engine bay and found something strange. The distributor, the pump assembly, the ignition wiring, every component had a code stamped on it.

Not part numbers like German machines, but interchangeable identifiers. The engineer lifted one piece into the light. This isn’t designed for this tank. It is designed for any tank. Eyes widened. America wasn’t building tanks. America was building systems. A pipeline of parts that could slot into anything, anywhere, anytime.

A student whispered, “How many spares do they have?” The engineer exhaled. A siren wailed in the distance. Not an air raid, a logistics alarm. British artillery had hit a bridge. Supply convoys rerouted. Delays everywhere. Krueger muttered. Our tanks will have to wait. The engineer nodded. That is our war. Germany waited. Germany repaired.

Germany perfected. America replaced. America resupplied. America flooded. Not with brilliance, but with volume. The lead engineer looked at the disassembled components on the ground, the parts laid out like organ pieces. This tank is not powerful. It is sustainable. The word landed heavy. Sustainable. Germany had designed a Ferrari for a world where you needed forklifts.

America designed forklifts. By dusk, the courtyard smelled of fuel and dust. Rain threatened. Wind whipped loose papers. The men were tired. But they all understood something critical. America wasn’t winning because their tanks were beautiful or invincible or deadly. America was winning because their tanks refused to disappear.

Not because they couldn’t be destroyed, but because they could be rebuilt faster than they died. A student whispered, almost afraid. How do you win against that? Rain finally came. Not a storm, just a steady, cold drizzle that soaked tools, uniforms, and pages of notes. The men worked under lanterns and canvas tarps.

Steel glistened, oil pulled in puddles. The courtyard smelled like a burnedout factory. They hadn’t expected to stay this long, but the Sherman wouldn’t stop revealing surprises. The lead engineer wiped water from his glasses and stared at the engine bay, not with contempt anymore, but with respect.

This tank wasn’t trying to impress him. It was trying to survive him. One machinist called out, “Sir, you should see this.” He pointed to a jagged section of armor where a shell had struck and failed to penetrate. Embedded in the armor was a removable panel bolted, not welded, into the hall. The engineer frowned.

“Why is this section shaped differently?” The machinist shrugged. It’s like they designed it to be replaced. Krueger overheard and scoffed. A clerk arrived breathless, delivering a typed report from German field units. The engineer skimmed it quickly. It contained data on tank losses, repair times, recovery operations, spare stock levels.

He rubbed his forehead. A tiger disabled on the eastern front. Transport required. 7 days to extract. 21 days to repair. Zero spare engines available. Factory backlogged. Fuel priority. The next day, two officers from higher command arrived. Clean uniforms, polished boots, the kind of men who wrote reports, not wrenched bolts.

They reviewed notes, photos, diagrams. One officer said, “Your findings suggest their machines are inferior.” The engineer raised an eyebrow. “Inferior? No.” The officer stiffened. “Then why do they break so often?” The engineer replied, “Be after the officers left,” Krueger smirked. “This will fix our report,” one machinist muttered.

It will fix nothing in the field. The courtyard went silent again. Truth wasn’t enough. Truth had to be acceptable. Germany didn’t lose because they lacked intelligence. They lost because they refused to adapt. The engineers stared at the tank. By nightfall, the engine components lay spread across sheets of canvas.

The Germans expected at least one catastrophic flaw, a fatal weakness, something that proved American tanks were rushed junk. They found wear. They found dirt. They found heat damage, but not failure. One machinist said quietly, “This engine died slowly, not violently.” The engineer nodded because it was used to its limit.

Another asked why a engineer told his students, “The tiger is a cathedral. The panther is a masterpiece.” He tapped the Sherman’s greasy, ugly engine block. This is a hammer. Krueger sneered. Hammers build nothing glamorous. The engineer replied, “Hammers build empires.” Krueger looked away. A runner arrived with new intelligence. American factories increasing tank output. Rail networks optimized.

Spare engines stockpiled. The final line. Even destroyed Shermans are salvaged for parts. Nothing wasted. One technician whispered. “They recycle tanks.” The engineer nodded. “Everything gets a second life.” Krueger scoffed. “We build things to last.” The engineer stared at him hard. They build things to return. When the night was nearly over, the lead engineer gathered his men.

Rain fell, lanterns flickered, mud swallowed footprints. He said, “American tanks are not strong individually. They are strong collectively. No single shareman wins a battle. A hundred sharemans do.” The students listened uneasy. He continued, “Germany built the best machines. America built the best system.” And then the most painful sentence of all. War favors this system.

He looked at the rain stopped just before dawn. The courtyard was silent except for the clink of tools being packed away. Men moved slowly, exhausted, heavy with thoughts they could not speak. The lead engineer gathered his notes, diagrams, and photographs, not as trophies, but as evidence of something that should have changed doctrine, something that would not.

When he entered the command building to submit his findings, the officer who had visited the night before stood waiting. Your report, the officer said calmly, needs to emphasize American weakness, not American strength. The engineer stared at him. Strength is all we found. The officer smiled coldly, then rewrite it. The engineer clenched his jaw.

If we present only what you want, our doctrine will never adapt. The officer stepped close. Germany does not adapt. Germany leads. The engineer whispered. Germany will lose. For a moment, time stood still. The officer did not slap him. He did not shout. He simply said, “You will destroy any notes that suggest otherwise.

” Orders were orders. Truth was irrelevant. Victory was ideology, not logistics. The engineer walked out without speaking. He felt no pride in obedience, only fatigue. When he returned to the courtyard, the others were preparing to reassemble the Sherman, not to test it, but to hide what they had learned.

A command had been issued. Tank must be stripped, photographed for propaganda, then destroyed. destroyed. Not studied, not replicated, not learned from, destroyed. One machinist muttered, “So no one can see what we saw.” The engineer nodded, “No one who matters.” As they worked, the morning sun broke through the clouds, illuminating the tank’s open hull like a stage.

It did not look like a trophy. It looked like a warning. Krueger approached the engineer quietly. For once, he did not look angry. He just looked tired. You really believe this simple thing helped them win? The engineer didn’t hesitate. Yes. Krueger stared at the disassembled parts. But it’s ugly, primitive, unrefined.

The engineer nodded. So is war. Krueger looked away. What about pride, craftsmanship, excellence? The engineer answered, “War does not reward excellence. War rewards endurance.” For the first time, Krueger had no argument, not because he agreed, but because he had no evidence left to deny it. They reassembled the Sherman piece by piece, sealing away the secrets they had uncovered, not to respect it, but to erase it.

One machinist muttered, “So no one can see what we saw?” The engineer nodded. “No one who matters.” As they worked, the morning sun broke through the clouds, illuminating the tank’s open hall like a stage. It did not look like a trophy. It looked like a warning. Krueger approached the engineer quietly. For once, he did not look angry.

He just looked tired. You really believe this simple thing helped them win? The engineer didn’t hesitate. Yes. Krueger stared at the disassembled parts, but it’s ugly, primitive, unrefined. The engineer nodded. So is war. Krueger looked away. What about pride, craftsmanship, excellence? The engineer answered, “War does not reward excellence.

War rewards endurance.” For the first time, Krueger had no argument, not because he agreed, but because he had no evidence left to deny it. They reassembled the Sherman piece by piece, sealing away the secrets they had uncovered, not to respect it, but to erase it. One machinist muttered, “So no one can see what we saw?” The engineer nodded, “No one who matters.

” As they worked, the morning sun broke through the clouds, illuminating the tank’s open hull like a stage. It did not look like a trophy. It looked like a warning. Krueger approached the engineer quietly. For once, he did not look angry. He just looked tired. You really believe this simple thing helped them win? The engineer didn’t hesitate. Yes.

The engineer wound slept for several days before the end of the war when he coordinated the advance of Germany’s armored divisions toward Prague. In Germany’s last feutal hope for a separate peace with the West, one of the last German tanks lasted only 20 minutes before being destroyed by an American javelin.

The German crew died without firing a shot. He stepped back from the tank and addressed his team, not as a commander, not as an academic, but as a man who had spent his life believing in perfection. Germany built machines that reflected who we wanted to be. Brilliant, precise, majestic. America built machines that reflected what war demanded. Cheap, fast, repable.

He gestured to the Sherman. This tank is not great because of what it can do once. It is great because of what it can do again. He paused, eyes weary. War does not measure quality. War measures availability. Not excellence, but persistence. Silence. The men listened, not because they were ordered to, but because they needed to understand.

A soldier ran in from the road, breathless. Mud on boots, rifle still wet from the night. Report: Enemy armor cighted to the west. American column Sherman type. Krueger frowned. How many? The soldier swallowed. Too many to count. The courtyard went still. Not because the enemy was coming, but because the enemy was coming again.

A machine replaced, crew replaced, unit replaced, a system replenished. War did not favor lions. War favored swarms. The lead engineer whispered, “There is the secret in motion.” Before they set charges to destroy the tank, the engineer placed his hand on the cold armor one final time. Not affection, not admiration, but acknowledgment.

This was not a masterpiece. It was not elegant. It was not something to be remembered. It was something that refused to disappear. He said quietly to no one in particular. We built for glory. They built for survival. Then louder. And survival wins wars. The charge is designated at noon. Not a dramatic explosion, not fire, not shrapnel in the air, just a dull thud as the hull buckled in on itself.

a factory product collapsing into scrap. The engineers watched silently. No cheers, no soldiers, no propaganda photographers, just men who had learned something dangerous and were now forced to forget it. Krueger muttered, “It feels wrong.” The engineer nodded. Truth often does. Weeks later, when Germany struggled to field tanks and America landed hundreds on distant shores, the engineer thought back to the Sherman.

Not its cannon, not its armor, not its engine, but its philosophy. a machine that demanded nothing except the chance to fight again tomorrow. He wrote in a private notebook, “War is not won by those who build the best things. War is won by those who build the most things that work.” And he ended with a final line.

The Sherman did not win because it was perfect. It won because it was enough.