Camp Concordia, Kansas, 1944. The train doors opened and Warner Hartman stepped into sunlight so bright it hurt. Behind him, 47 German soldiers shuffled onto a platform where American guards waited, rifles casual against their shoulders. The guards were joking with each other. One was eating a hamburger.

Wernern had expected barbed wire in brutality. Instead, across the yard, he saw women. American women in civilian clothes, carrying clipboards, walking freely among armed soldiers. His propaganda training had promised a nation mobilized for total war. This looked like a county fair. The boxars had carried them from the east coast for 3 days.

Wernern and his men paratroopers captured in Normandy had spent the journey braced for the worst. Cramped conditions, limited water, the uncertainty of what awaited at the journey’s end. Through the slats they had watched America scroll past, endless farmland, towns that showed no bomb damage, factories with smoke rising from chimneys, working at full capacity, cars on roads, trains hauling freight, the infrastructure of a nation utterly untouched by war.

It’s propaganda, Klaus Bower had whispered. a former Berlin clerk who’d been drafted in 1943. They’re showing us stage scenes, making us think they’re stronger than they are. But the scenes kept coming. Mile after mile of undamaged countryside. Wernern, who had seen Hamburg burning, Dresden reduced to ash, every German city scarred by bombing, couldn’t reconcile what he was seeing. If this was propaganda, it was remarkably thorough.

The train stopped at Concordia, a small Kansas town surrounded by wheat fields that stretched to horizons too wide to comprehend. The guards who opened the doors were young, maybe 20, relaxed in a way that suggested they’d done this many times. “Welcome to Kansas, boys,” one said in accented German. “You’ll be processed, fed, assigned barracks.

No trouble from you, no trouble from us. Fair enough. Wernern nodded, too stunned to speak. They were led into a processing building where American clerks, several of them women, sat behind desks with typewriters. One woman, maybe 30, with dark hair pinned up and lipstick the color of cherries, gestured Werner forward.

Name? She asked in German. Hartman. Wernern. Sergeant. She typed without looking up, her fingers quick and efficient on the keys. Age: 24. Captured where? Normandy. June 15th. She filled out forms with practiced ease, stamped documents, attached a photograph they’ taken of him at the coast. Then she handed him a card.

This is your prisoner identification. Don’t lose it. You’ll need it for meals, mail, work assignments. Next, Wernern stared at her, a woman doing clerical work in a military facility with male prisoners present. The propaganda had insisted American women were kept away from war, that the US lacked the moral strength to mobilize fully.

Yet here she sat, unmarried from the look of her bare ring finger, working directly with enemy soldiers without apparent concern. Next, she repeated, impatient now, Warner moved on, his mind struggling to process. The barracks were wooden, clean with 16 bunks to a room. Each bunk had a mattress, two blankets, a pillow. A foot locker sat at the end of each bed.

The windows had screens, but no bars. The door had no lock. “Where are the guards?” Klouse asked. Outside, another prisoner replied, a veteran named Otto, who’d been transferred from another camp. They patrol the perimeter, check in occasionally, but they don’t lock us in at night. We’re on an honor system.

Honor system? Wernern couldn’t comprehend it. We’re prisoners of war. Yeah. And where are you going to go? Otto gestured at the window. Kansas stretched in all directions, flat and endless. You wouldn’t make it 10 miles before some farmer called the authorities. Besides, the food’s better here than it was in the army.

Why would anyone run? That evening, they were taken to the messaul. Wernern expected thin soup, black bread, maybe some potatoes. What he got was a tray piled with beef stew, fresh bread with butter, green beans, apple pie, and coffee with cream and sugar. He sat at a long table and stared at the food around him.

Other prisoners were eating with single-minded focus, but Wormer couldn’t move. In his last year in the army, rations had dwindled to almost nothing. He had watched comrades grow thin, watched them fight over scraps, and now, as a prisoner, he had more food than he’d seen in months. Klouse sat beside him, tears running down his face, chewing bread with his eyes closed.

How do they have this mucher whispered? Otto, at the end of the table, answered. Because they grow it. Kansas produces more wheat than all of Germany. The Midwest produces more cattle than we’ve ever had. They aren’t starving. They never were. Everything we were told about American weakness was a lie. Wernern took a bite of the stew.

The meat was tender, seasoned with herbs he didn’t recognize, vegetables cooked perfectly. He had to stop eating twice because his stomach, unused to such richness, threatened to rebel. After dinner, they were given an hour of free time before lights out. Some men played cards. Others wrote letters that would be censored and sent through the Red Cross.

Wernern walked to the edge of the compound and looked out at the Kansas landscape. The sun was setting, painting the sky orange and pink. The wheat field swayed in the evening breeze. Somewhere in the distance, a dog barked. It was peaceful, quiet, nothing like the war. A woman’s laughter carried across the yard from one of the administrative buildings. High and clear without fear.

Wernern thought about his sister back in Berlin, who hadn’t laughed in years, who flinched at loud noises, who slept in the cellar even when the bombers weren’t overhead. “Sergeant Hartman.” An American guard had approached, young with red hair and a Nebraska accent. “You settling in?” “Okay.

” “Yes,” Warner said carefully. “Good. You’ll get work assignments tomorrow. Probably farm labor or camp maintenance. pays 10 cents an hour in camp script. You can use it at the canteen for cigarettes, candy, that sort of thing. Any questions? The women, Wormer said, the words escaping before he could stop them.

Why are they here in a prisoner camp? The guard looked confused. Why wouldn’t they be? They’re clerks, translators, Red Cross workers. We need staff. They need jobs. What’s strange about that? In Germany, women don’t work in military facilities. Well, the guard said, “You’re not in Germany anymore.

” By the end of the first week, Wernner had been assigned to farm labor. Each morning, he and 20 other prisoners were driven in trucks to nearby farms where they helped with harvest. The farmers paid the military for the labor. The prisoners received their 10 cents an hour. The work was hard, but not cruel. The farmers treated them like hired hands, showed them how to operate equipment, shared water breaks, and sometimes lunch.

One farmer, a man in his 60s named Harold, spoke to Werner while they were mending a fence. You know much about farming. No, Wernern admitted. I worked in a bookstore before the war. A bookstore? Harold wiped sweat from his brow. What kind of books? All kinds. literature, history, technical manuals, whatever people wanted.

You miss it? Wernern was surprised by the question. Yes, very much. Harold nodded. War takes people from their lives. Turns them into things they never meant to be. I was in the first war. France saw things I’d rather forget. When it ended, I came back here, bought this farm, married my wife, put it all behind me.

You’ll do the same someday. If there’s anything left to go back to, there will be. Might not look like you remember, but there will be something. There always is. That evening, Warner visited the camp canteen for the first time. It was a small building stocked with items prisoners could purchase with their script. Cigarettes, chocolate bars, razor blades, soap, writing paper.

Behind the counter stood a woman in her 40s with graying hair and glasses. “What can I get you?” she asked in German. Wernern studied the shelves. Chocolate bars in colorful wrappers. American cigarettes in neat packs. Everything clean and organized and abundant. Chocolate, he said finally. And writing paper. She handed him both items. That’ll be 20 cents.

He gave her his script. She counted it carefully and smiled. You’re new. Just arrived last week. Yes. Where from originally? Hamburg. Her expression softened. My husband’s family came from Hamburg. In the 1880s. I’ve never been, but he used to tell me about it. Beautiful city. He said it was. Wernern said quietly. Before the bombing, she was quiet for a moment. War destroys beautiful things.

That’s what it does best. She handed him his change. I hope when you go back, you can help rebuild it. Wernern took his chocolate and paper back to the barracks. He sat on his bunk and opened the chocolate bar Hershey’s, the rapper said, and took a small bite. It was sweet, almost too sweet, nothing like the dark German chocolate he remembered, but it was real and abundant, and he could have more whenever he wanted.

Klouse watched from the next bunk. Strange, isn’t it? Being treated like humans. The women especially, said, “They’re everywhere, working, talking to us, unafraid. How can they be unafraid?” Because they won, another prisoner said from across the room, a pilot named Friedrich, who’d been shot down over France. They won so thoroughly that they don’t need to fear us.

We’re not threats. We’re just defeated men far from home, eating their chocolate and picking their wheat. Warner thought about that through the evening and into the night. The humiliation wasn’t in the captivity. It was in the kindness, the ease with which America treated them well, as if it cost nothing, as if abundance was simply the natural state of things. By August, the camp had established routines.

Work in the mornings, meals at set times, evenings free for recreation. The Americans encouraged sports soccer for the prisoners, baseball for themselves, and on weekends the camp hosted matches. Wernern had never understood baseball. The rules seemed arbitrary. The slow pace punctuated by sudden action, but the American guards loved it.

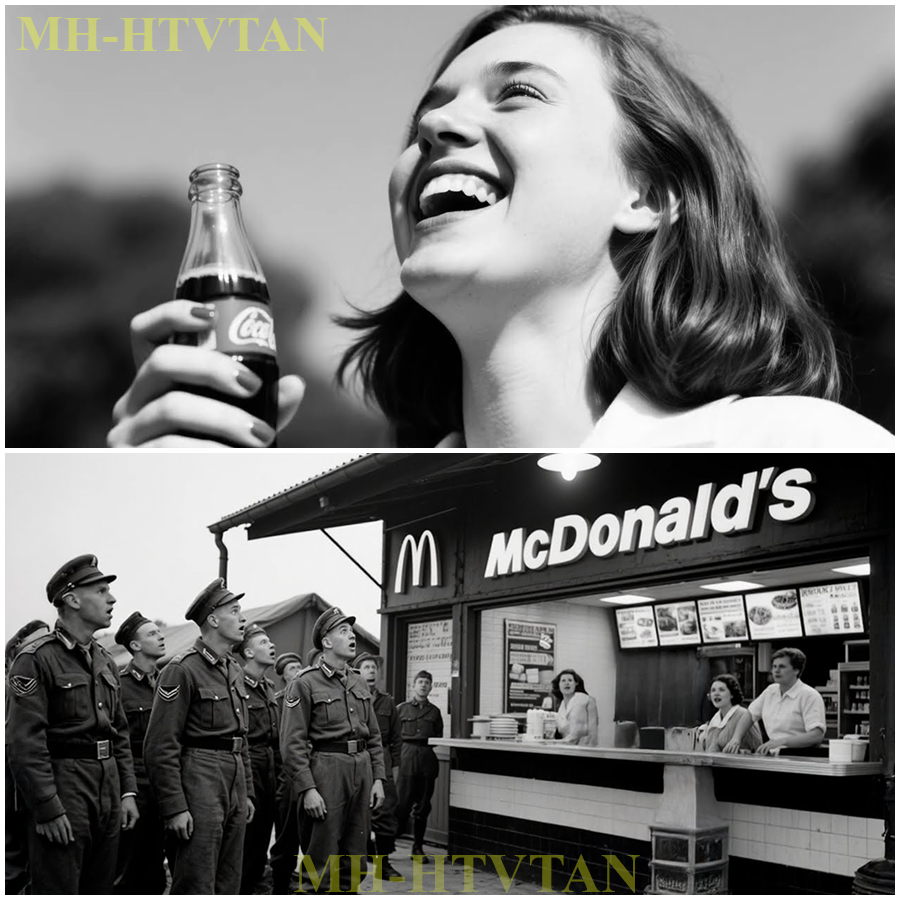

And on a Saturday in mid August, they organized a game between two military units stationed at the camp. Prisoners were allowed to watch from the sidelines. Wernern sat on the grass with Close and Otto trying to follow the action. American women sat nearby clerks and translators and Red Cross workers eating hot dogs and drinking Coca-Cola, cheering when something good happened.

One woman, younger than the others, maybe 22, sat close enough that Worer could hear her explaining the game to her companion. See, he’s trying to steal second base. If he makes it before the throw, he’s safe. If not, he’s out. Her companion, an older woman with gray hair, nodded. “Seems like a lot of running for very little gain.

” “That’s baseball,” the younger woman laughed. Wernern found himself watching them more than the game. The ease of their conversation, a casual way they sat in public, legs crossed, eating food without fear of shortage. The younger woman’s fingernails were painted red, red, as if she had time and resources for such things. while the world burned.

Sergeant Harkman, an American officer had approached a captain with a friendly face. You play soccer a little, Wernner admitted. Before the war, we’re organizing a match next week. Prisoners versus guards. Friendly competition. You interested? Wernern hesitated. Is that dot dot allowed? The captain looked confused.

Why wouldn’t it be? It’s just soccer. In Germany, guards don’t play sports with prisoners. Well, the captain said, echoing the young guard from Worer’s first week. You’re not in Germany anymore. So, you in or not? Yes, Warner said. I’m in. The soccer match became a camp event. Prisoners trained in the evenings. Americans did the same.

The women helped organize it, setting up goals, marking boundaries, arranging for refreshments. A younger woman, Wernern, had noticed turned out to be named Mary, a Red Cross worker from Ohio, who spoke decent German. She approached Werner before the match. “Good luck today. I hear you’re quite good.

I’m very rusty,” Wernern said in English, then surprised at himself for trying. Mary smiled. Your English is good. I studied in school before everything. What did you want to be before the war? A teacher. Literature. That’s nice. Important. She paused. My brother’s in Europe fighting. I think about him every day wondering if he’s safe, if he’s scared.

I look at you guys here and I try to remember that you’re someone’s brother, too. that you wanted to be teachers and farmers and bookstore owners, that the war took you from your lives just like it took him from ours. Wernern didn’t know what to say. The humanity in her voice was too much, too direct, too honest.

Anyway, Mary said, suddenly shy. Good luck today. The match was competitive. The prisoners won 3 to2 in a game that saw both sides playing hard but fair. When it ended, the Americans shook hands with the Germans, clapped them on the shoulders, congratulated them on good plays.

That evening at dinner, the mood in the mess hall was lighter than Werner had seen it. Men were laughing, replaying goals, arguing about calls. The American guards joined in the manter, teasing their own team’s goalkeeper. “We were robbed,” one guard said in German, grinning. That second goal was offside. It was clean. Klaus shot back, also grinning. You just have a terrible defense.

Watching this, Herner felt something crack inside him. Not break. Exactly. More like thaw. The propaganda had prepared him for cruelty, deprivation, humiliation. It had unprepared him for this, for being treated like a human being by people who had every reason to hate him. In September, prisoners were allowed to write home.

The letters would be censored, but the Red Cross had established reliable mail routes, and most letters eventually reached their destinations. Wernern sat with blank paper for an hour before he could begin. What did he write? How did he explain this? His family was in bombed out Hamburg, probably hungry, definitely scared, living under occupation or worse.

and he was in Kansas eating beef stew and playing soccer and being treated with more dignity than he’d descen in his last year in the German army. Finally, he wrote, “Dear mother and father, I am alive and safe. The Americans have treated us well. We have food, shelter, work. I am healthy. Please do not worry about me. Kansas is very flat. The sky goes on forever.

I work on farms and am learning about wheat. The people here are kind even though we are enemies. I do not understand it, but I am grateful. I think about you every day. I hope you are safe. I hope the house still stands. I hope we can be together again when this is over.

I don’t know what I’m coming home to or what kind of Germany will be left, but I promise you, I will come home. I will help rebuild. I will teach again if schools still exist. I will not let the war make me forget what I was before. Your son Werner. He sealed the letter knowing the sensors would read it, hoping it would reach Hamburg, wondering what his parents would make of it.

Around him, other prisoners were writing similar letters. Klouse wrote to his wife describing the food in detail because he knew she would want to know he wasn’t starving. Otto wrote to his mother, carefully avoiding any mention of how good the conditions were, not wanting her to feel worse about her own suffering.

Friedrich, the pilot, wrote nothing. “They’re all dead,” he said flatly. “My family was in Berlin. The bombing, there’s no one left to write to.” Wernern wanted to offer comfort, but had none to give. The war had stolen so much that even imprisonment in a kind place couldn’t restore it. By October, the camp canteen had expanded. More products appeared on the shelves.

Razors, toothpaste, magazines in German, even small radios prisoners could purchase. The woman who ran it, whose name was Helen, explained that as prisoners earned more script, demand had increased. “You boys are good workers,” she said to Wernner. one afternoon. The farmers love you. Say you work harder than most of the local help. We’re trying to earn privileges, Warner said.

Honestly, smart. Helen restocked a shelf with chocolate bars. Though between you and me, I think you’d be treated well regardless. That’s just how we do things here. Why? The question escaped before Werner could stop it. Why treat enemies well? Helen paused, considering.

Because you’re not really enemies, are you? You’re soldiers who followed orders. Same as our boys. The enemy is whoever started all this. Whoever decided war was the answer. But you, you’re just a young man who wanted to run a bookstore. That’s not an enemy. That’s just someone who got caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

She went back to stocking shelves, leaving Wernern to process her words. That week, something new appeared at the canteen. Hamburgers. Not fresh, but canned meat patties that could be heated and served on buns. Helen offered them once a week on Saturdays for 25 cents each. The first Saturday this was available, Wernner bought one. The meat was processed. The bun was soft white bread. The whole thing was garnished with mustard and a pickle.

It was nothing like German food, nothing refined or traditional. It was pure American efficiency fast, cheap, abundant. It was also delicious. Klouse ate his in four bites, then bought another. I can’t believe we’re eating like this. As prisoners, the propaganda said they were weak, Friedrich said quietly, eating more slowly.

said their materialism made them soft, that they couldn’t sustain a real war. But look at this. They feed us better than our own army fed us. They have so much they can afford to be generous with enemies. That’s not weakness. That strength we never understood. Wernern thought about the women again. The way they worked alongside men without fear.

The way they dressed nicely, wore lipstick and nail polish, maintained their individuality even in the middle of war. The propaganda had called this decadence moral decay. But maybe Wernern thought it was just confidence. The confidence of a nation so secure, so abundant that it didn’t need to control every aspect of life to maintain power. November brought cold and the first snow.

The prisoners were issued winter coats, gloves, boots, quality items, not threadbear or makeshift, but actual functional winter gear. Wernern’s coat was wool lined with flannel, warmer than anything he’d owned in the German army. Work shifted to indoor tasks.

Some prisoners were assigned to camp maintenance, others to workshops where they repaired equipment or made furniture. Wernern was assigned to the library, helping catalog and shelf books. The library was Helen’s idea. She had argued that prisoners needed mental stimulation, that boredom bred trouble. The camp commander agreed, and now there was a small room with 200 books, half in German, half in English, and several German language newspapers and magazines.

Wernern spent his days organizing books and his evenings reading them. German classics, Gerta, Schiller, Hina, American novels in translation, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald. He read about American literature, American history, trying to understand the country that had defeated his. Mary, the Red Cross worker, often visited the library. She was helping prisoners who wanted to improve their English, teaching informal classes twice a week.

You should join, she told Warner. Your English is already good, but you could get better. Why would I need better English? For after the war, when you go home and rebuild, knowing English will help. Trade, diplomacy, whatever comes next. Languages are bridges. Wernern considered this. The idea of after the war had seemed impossibly distant, but now with Germany clearly losing, it was becoming real.

There would be an after. He would survive to see it, and Mary was right. English might matter. He joined her classes. Twice a week, he and 10 other prisoners sat in the library while Mary taught them American idioms, corrected their pronunciation, explained cultural references that didn’t translate.

Why do Americans say break a leg for good luck? Klaus asked. That makes no sense. Mary laughed. Theater superstition. Saying good luck is bad luck, so you say the opposite. Your culture is very strange, Klaus said. But he was smiling. During one class, Mary brought in American music magazines.

Part of learning English is understanding American culture, and a big part of that is music. She showed them pictures of big band leaders, jazz clubs, singers with names like Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby. Wernern studied the images of American nightife, people dancing, laughing, living despite the war. “Do people really still do this?” he asked. “Go to clubs and dance while there’s a war?” “Of course,” Mary said. “Life doesn’t stop because there’s fighting.

People still work, fall in love, get married, have babies, go to movies and dances. That’s what we’re fighting for, isn’t it? The right to keep living normal lives. Warner thought about Hamburg, about Berlin, about German cities where normal life had ceased to exist, where people lived in sellers, fled from bombing, scavenged for food. The contrast was devastating. December brought an announcement.

The camp would celebrate Christmas. Prisoners could decorate their barracks. There would be a special meal. Packages from home would be distributed if any had arrived through the Red Cross. The women of the Red Cross organized the event. Mary and Helen and a dozen others spent weeks planning, acquiring materials, coordinating with the camp administration. They set up a Christmas tree in the mess hall.

A real tree 8 ft tall decorated with lights and handmade ornaments. Warner watched them work with growing bewilderment. These American women whose country was at war with his were preparing a Christmas celebration for German prisoners. The cognitive dissonance was almost painful. On Christmas Eve, the mess hall was transformed. The tree glowed with lights.

Tables were decorated with pine branches and candles. The smell of roasting turkey filled the air. The meal was extraordinary. Turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes with gravy, cranberry sauce, rolls with butter, green beans, pumpkin pie with whipped cream, coffee and cider, chocolate. Warner sat with his usual group, but no one spoke.

They were too overwhelmed. Around them, American guards and camp staff moved through the room, wishing prisoners merry Christmas, shaking hands, treating them like guests rather than captives. Mary approached Worner’s table with a small package. This came for you. Through the Red Cross, Wernern’s hands trembled as he opened it.

Inside, a letter from his mother, a photograph of his family’s house, damaged, but still standing, and a hand knitted scarf. The letter was brief. His mother’s handwriting shaky. Wernern, we are alive. The house was hit but not destroyed. Your father is working in rubble clearance. Your sister is safe. We think of you everyday. Please take care of yourself.

Come home when you can. We will rebuild together. Love, mother. Wernern held the scarf, trying not to cry. around him. Other prisoners were opening their own packages, reading their own letters, confronting the reality of what waited for them at home. Helen stood at the front of the room and called for attention. “I want to say something,” she said in careful German.

“I know this is complicated for all of you, being here, being treated well while your families suffer. But please know that we don’t celebrate your suffering. We celebrate the hope that one day wars will end, that people can go home, that enemies can become just people again. She raised her glass to peace. To going home, to rebuilding, the room echoed to peace.

Wernern drank, tasting cider that was too sweet. Feeling tears he couldn’t stop. The paradox was too much. He was a prisoner being celebrated by his capttors. He was fed while his family starved. He was warm while German cities froze. Later in the barracks, Klouse said what they were all thinking.

How do we go home after this? How do we tell them what it was like here? We don’t, Friedrich said flatly. They won’t believe it anyway. They’ll think we’re making it up, trying to make ourselves feel better about being captured. or they’ll hate us for it, Otto added. For being treated well while they suffered. Worer thought about Mary teaching English.

About Helen organizing Christmas, about American women working without fear in a military facility. About hamburgers and chocolate and soccer matches. We tell the truth, he said finally. Not to make ourselves feel better, but because it’s important. Because whoever builds the next Germany needs to understand what we learned here. That strength doesn’t require cruelty.

That abundance doesn’t mean weakness. That treating people with dignity isn’t a luxury. It’s a choice. And America chose it, even with enemies. By March 1945, the war’s end was visible on the horizon. Radio broadcasts brought news of Germany’s collapse, cities falling, armies retreating, leadership in chaos. In the camp, the mood shifted.

The prisoners knew they would go home eventually, but to what? Wernern continued his routines. Work in the library, English classes with Mary, occasional farm labor when needed. But his mind was elsewhere, calculating the ruin waiting in Hamburg, wondering if his family was still alive, trying to imagine rebuilding from nothing.

One afternoon, Mary found him in the library staring at a map of Germany, thinking about home, trying to remember what it looked like before she sat beside him. My brother came home last month from France. He was injured, sent back. He said, “The destruction over there is beyond anything we can imagine. Cities that don’t exist anymore.

People living in ruins. That’s what I’m going back to.” “Yes,” she said quietly. “But you’re going back with something most people won’t have. You’ve seen how another country does things, how abundance can create generosity instead of greed, how strength can coexist with kindness. That knowledge is valuable.

Or it will make me a pariah, someone who lived well while others suffered. Maybe, but I don’t think so. I think people will be too busy surviving to worry about that. And when they’re ready to rebuild, they’ll need people who remember that there are different ways to organize a society. Better ways, Warner looked at her.

Why do you care about what happens to Germany after? Because Mary said slowly, “The war taught us that what happens anywhere eventually affects everywhere. Germany falling apart after the last war led to this war. If we want peace to last, we have to help rebuild. Not out of charity, but out of self-interest. A stable, prosperous Germany benefits everyone.” She stood up.

You’re a teacher, Wernner. When you go home, teach. Teach the next generation what you learned here. That might matter more than you think. May 8th, 1945. Germany surrendered. The news spread through Camp Concordia like wildfire. Prisoners gathered around radios, listening to broadcasts in German and English, trying to process that it was finally over. Wernern felt nothing.

Not relief, not grief, not joy, just numbness. The war that had consumed 5 years of his life was done and he didn’t know how to feel about it. The camp administration announced that repatriation would begin in phases. Younger prisoners, those with families waiting, would go first. Others would stay until transportation could be arranged and conditions in Germany stabilized enough to receive them.

Wernern was in the second group. He would leave in June. The final weeks were strange. Work continued, but without purpose now. Men moved through their routines mechanically, thinking about home, dreading home, trying to prepare for what awaited. On Warner’s last day, Helen called into the canteen. I wanted to give you something.

She handed him a package, several chocolate bars, some cigarettes, soap, and a small book. An English German dictionary for the rebuilding, she said. The chocolate and cigarettes will be worth more than money in Germany right now. The soap will help you stay clean, and the dictionary will help you keep learning. Thank you, Mner managed. Don’t thank me. Just remember what you saw here. Remember that people can be kind.

When you’re home and everything is hard and it seems like the world is nothing but cruelty, remember Kansas. Remember that kindness is possible. Mary organized a farewell for the English class students. She brought cookies, real cookies, with chocolate chips and made coffee. They sat in the library one last time, these German prisoners and their American teacher.

I want you all to know, Mary said, that teaching you has been one of the most important things I’ve done during this war. You were enemies when you arrived, but you’re not enemies now. You’re just people I hope will go home and help build a better Germany. A Germany that doesn’t need wars. Klouse raised his coffee cup. To Mary, to Helen.

To all the American women who showed us that strength and kindness can coexist. They drank to that. The next morning, Wernern and 40 other prisoners boarded a train heading east. They would go to a processing center in New York, then board ships for Europe. The journey home had begun.

As the train pulled away from Camp Concordia, Wernern watched through the window as Kansas disappeared. The flat land, the endless sky, the town where he had learned that everything he’d been taught about America was wrong. Helen and Mary stood on the platform, waving. Wernern waved back, knowing he would never see them again, knowing he would remember them forever.

Warner Hartman returned to Hamburg in July 1945. The city was rubble. His family’s house stood but was barely livable. His father was thin, his mother exhausted, his sister traumatized by years of bonding. But they were alive. And Wernern had cigarettes and chocolate to trade for food and building materials. He started teaching again in 1947 in a makeshift school in a partially repaired building.

His students were children who had known nothing but war, who associated authority with cruelty, who had been taught that might made right. Wernern taught them literature. He taught them English, and he told them about Kansas. I was a prisoner, he would say, but I was treated with dignity.

The Americans had every reason to be cruel, but they chose kindness instead. They fed us well, housed us decently, taught us skills, treated us like humans. Not because they were weak, but because they were strong. Strong enough to be generous. Some students didn’t believe him. How could enemies be kind? It didn’t match what they’d been taught.

But Wormer persisted. He showed them the dictionary Helen had given him. He taught them phrases Mary had taught him. He described hamburgers and baseball and American women working without fear. This is what I want you to understand. He would tell them.

Germany lost because we were weaker, yes, but also because we built our strength on cruelty. And cruelty is expensive. It requires constant enforcement. Kindness is cheaper. It builds loyalty freely given. America understood that. We didn’t. That’s why they won. By the 1950s, Wernern was teaching at a proper school in a rebuilt building.

His students went on to become teachers themselves, business people, politicians, the generation that would rebuild Germany into something new. In 1962, he received a letter from Mary. She had married, had children, was still working with the Red Cross. She had seen his name in a German newspaper, an article about innovative teaching methods in Hamburg.

I always knew you’d be a good teacher, she wrote. I hope Kansas served you well. I hope you’re passing on what you learned there. The world needs more people who remember that kindness is possible. Worner wrote back a long letter describing his work, his students, his life in rebuilt Hamburg. He thanked her for treating him like a human when he was an enemy.

He told her that her lessons had reached hundreds of students now, that the ripples of her kindness were spreading through a generation. He never heard back. But years later, he learned that Mary had died in 1964, cancer, far too young. In her obituary, her children mentioned that she had spent the war working with prisoners, that she had believed in rehabilitation and education, that she had lived her values even when they were unpopular.

Wernern kept teaching until 1978 when he retired. By then, Germany was prosperous, democratic, integrated into Europe. The generation he had taught was leading the country. And they remembered his lessons about Kansas, about kindness, about choosing to be generous from a position of strength. The camp at Concordia was dismantled in 1946.

The buildings torn down, the land returned to farming. Nothing remains now, but memories and a small historical marker on Route 81. noting that prisoners of war once lived there, worked there, learned there that abundance need not breed cruelty. Helen died in 1971, Mary in 1964, Wormer in 1983, but the lessons survived, passed through classrooms in Hamburg, written in memoirs and letters, remembered by a generation that rebuilt Germany from ruins, guided partly by the memory of enemies who chose to be kind.

Kansas 1,944 1,945 Flatland under enormous sky American women working without fear. Hamburgers in a prison canteen. English classes in a makeshift library. Soccer matches between guards and prisoners. Christmas celebrations for enemies. Small things, local things. Just one camp among hundreds. just a few dozen prisoners among millions.

But small lessons repeated enough eventually reshape the world. And sometimes the strongest weapon isn’t violence. It’s the simple choice to treat enemies like humans. Even when you don’t have to, especially when you don’t have to. The war ended. The prisoners went home. The lessons remained. And in classrooms across Germany for decades after, students learned that strength and kindness weren’t opposites. They were partners.

That lesson came from Kansas. From women who worked without fear. From hamburgers in a canteen. From the simple revolutionary act of treating defeated enemies like people who would one day need to rebuild a better world.