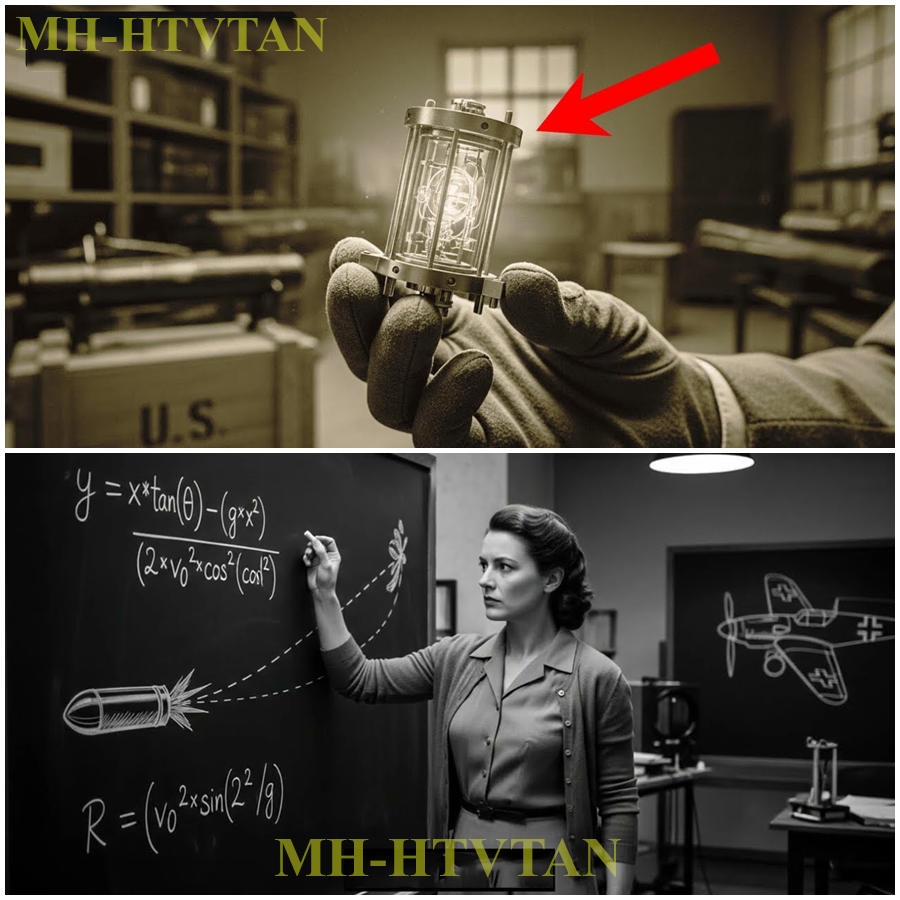

A metal crate arrived at a German test facility outside Berlin. The markings on the side were American. The crate had been taken from a shot down bomber. Inside was not a bomb, not a gun. It was something smaller, a gadget, as the German officers called it. They did not know the exact name. They only knew what it did.

where this gadget was used, German aircraft fell from the sky at distances where normal fuses should have failed. The crate was opened on a workbench. Engineers leaned in. They expected to find a new explosive or a clever piece of clockwork. What they found instead was a device that looked simple, almost ordinary. But when they understood how it worked, many of them reached the same quiet conclusion. Germany had already lost, and this gadget was only the proof.

The story began weeks earlier. Over a gray, cold landscape, a formation of American bombers was returning from a mission. Their targets had been rail lines and factories. German fighters had attacked. Flack batteries had fired. One B-24 had lagged behind. It trailed smoke. One engine was out.

German anti-aircraft crews watched. The bomber lost altitude. It tried to keep heading west. It failed. The aircraft crashed in a patchwork of fields and woods. Local soldiers and police reached it first. The wreck burned. Then it smoldered. The bodies were removed, the papers collected. A small team was sent to examine the remains.

They were interested in radios, in navigation gear, in anything new. One sergeant noticed something odd. Fragments of shells had torn through the bomber’s wings, and yet some of the flack bursts had been alarmingly close to the aircraft’s own altitude. He had heard rumors. Rumors of a new American fuse that could explode at the right distance without a direct hit.

Later, in the twisted metal of a Bombay rack, someone found something strange. A small aluminum cylinder, electrical contacts, glass components, no clockwork, no simple impact striker. It went into a bag, then into a crate with a note. Possible new fuse type. Send to Berlin. The crate reached a Luftvafa research center used for weapons analysis. Ober engineer Carl Fol stood over it.

He was in his 40s, thin, serious. Before the war, he had worked with radios and industrial electronics. He liked clean diagrams and clear numbers. He did not care for slogans. He did not repeat propaganda. His job was simple. Look at what the enemy builds. Understand it. Copy it if possible. Defeat it if not.

The label on the crate mentioned a bomber crash. Possible new fuse. American origin. Folk had seen many fuses, time fuses with clockwork, impact fuses with springs and needles. He opened the crate. Inside, wrapped in cloth, were several damaged pieces of bombs and shells. Among them, the small object from the bomber, bent, but recognizable. He placed it on a clean tray.

His assistant, Vber, watched. It looks ordinary, Vber said. Folk shook his head. In 1944, he replied, nothing that reaches Berlin in a crate marked urgent is ordinary. Before they could understand what was new, the team reviewed what was old. A normal artillery or flack fuse has a simple logic.

Either it explodes after a certain time using gears and springs or it explodes when it hits something using a mechanical impact trigger. Both methods have limits. Time fuses must be set before firing. If the estimate is wrong, the shell bursts too high, too low, or too far away. Impact fuses need a strike. If the shell passes near a plane but does not hit it, nothing happens. In theory, you can adjust for this with numbers, tables, training.

In practice, human error and chaotic conditions make precise timing difficult. By 1944, German flack crews were very experienced. But American reports suggested something else was happening. Shells were not just exploding near planes by luck. They were exploding near planes again and again at useful distances. Something was changing the rules.

Vog’s team began a careful disassembly. The device was already damaged from the crash. Parts were deformed, but the internal structure was mostly intact. They removed the outer casing. They placed each piece on a marked cloth. Weber frowned. I don’t see any gears, he said. Good, Voke replied. He picked up the largest fragment.

There was a small glass tube, tiny coils of wire, condensers, resistors. This is not a clock, he said. It is a circuit. Weber hesitated. electronic. Yes. Vote was quiet for a moment. Find me all previous reports, he said. Anything mentioning strange air bursts, anything mentioning fuses that do not behave like normal ones. Weber nodded and left.

Voke remained at the bench. He turned the small glass tube between his fingers. He recognized the pattern, high frequency, short pulses. He had seen similar designs in radar equipment. The thought formed slowly. The fuse did not wait for impact. It sensed proximity. If that was true, this was more than a fuse. It was a tiny disposable radar.

That same afternoon, Voke wrote on the board, he drew a gun, a shell, a plane. Underneath three words: time, impact, proximity. Time and impact were familiar columns. He left them blank. Under proximity, he wrote simple statements. Fuse reacts when target is near.

No direct hit required distance-based trigger using radio reflection. Another engineer entered. Her name was Anna Richter. She handled mathematics. Vog pointed at the board. If this is correct, he said, “Our anti-aircraft guns do not need perfect aim. They only need approximate solutions. The shell handles the last part. RTOR nodded slowly.

And if the shell can do that alone, she said, “Then every gun battery becomes more efficient. Fewer shells per aircraft, higher real kill rate.” She hesitated. “Is that what we are seeing?” Vog looked at the reports Vber had just brought in. graphs, intercepted messages, scattered notes from the front.

Yes, he said, on some fronts, especially against our V1 sights, their anti-aircraft fire has become far more accurate, suddenly without obvious new guns. He tapped the tray with a half disassembled edgit. I think we are looking at the reason. To test their hypothesis, the team built models on paper. They calculated distances. They modeled shell paths. RTOR ran through basic equations.

If a shell with this gadget flies near a plane, she said, “It can detonate when it detects reflected radio energy strong enough to indicate proximity.” She drew a curve. The shell does not ask will I hit. It asks am I close enough for fragments to matter. In combat, this changes many things.

A flack battery does not need a perfect solution to the firing problem. It only needs a good enough one. Shells that would once sail past a target and explode uselessly now burst close enough to throw metal through wings, engines, and crews. For pilots, this feels different. Instead of seeing random distant bursts, they see shells exploding in patterns that should not be so precise.

To them, the sky begins to look less like random danger and more like a thinking enemy. Once the basic concept was clear, the next question was obvious. Can we copy it? Someone asked. In theory, yes. The physics was not new. Germany had its own radar, its own highfrequency research. The problem was not knowledge. It was capacity. Voke looked again at the tiny components, miniature valves, delicate coils, carefully made glass.

Each fuse was a small radio set designed to be thrown away after a single use. To make such devices in large numbers, you needed factories that could produce millions of precise parts and then pack them into shells by the thousands. You needed reliable electricity, stable supply of materials, and large-scale electronics industry that could afford to treat complex circuits like cheap items.

In 1944, Germany did not have that freedom. RTOR said it first. We are struggling, she said, to keep our existing radar and radio network supplied. We do not have enough vacuum tubes for everything we already use. She gestured at the fuse. To us, this is a small marvel. To them, it is ammunition.

A week later, Vog wrote his formal report. The tone was restrained, technical, dry. He described the internal structure, the electronic principle, the likely operating frequency. He explained how such a fuse would improve anti-aircraft fire. He mentioned its likely role in defending against Germany’s own flying bombs.

At the end, in a short paragraph, he added something else. He noted that while the basic idea could be reproduced, the large-scale manufacturer of such devices would require an industrial base capable of producing precision electronic components in quantities far beyond our current capacity. He closed the folder. Vber read the summary.

So they have this now, he said. Yes, Voke replied. And we do not. We might build a few. We might test them, but we will not build hundreds of thousands. Vber nodded slowly. And if they can, Vult looked at the bench at the small broken gadget in front of him.

Then he said quietly, “They’re fighting this war on a scale we cannot reach.” He did not raise his voice. He did not make a dramatic statement. He simply filed the report and went back to work. But in his own mind, he had already accepted what the gadget meant. Germany had not lost because of this one device. It had lost because it was now clear what the other side could afford to throw away.

The first people to feel the difference were not engineers. They were pilots. Oberloit n Marcus Han flew a fighter on the Western Front. He had attacked bombers since 1943. He knew flack. Flack had a rhythm. You learned it. Shells burst too high, too low, too far off. You flew through gaps. You trusted timing. If the bursts lagged, you dove. If they walked toward you, you turned early.

In late 1944, something changed. On a mission toward the Low Countries, his squadron climbed through a familiar band of anti-aircraft fire. Only this time, the bursts felt different. They were not random. They crowded him. They followed the bombers more closely than before.

After the mission in the debriefing hut, another pilot spoke first. “Flack is getting better,” he said. “Too good.” Han shook his head. “Not better,” he replied. “Smarter.” “They did not know why. They only knew that the air around the American formations was becoming a more precise kind of dangerous. Later, when rumors of new fuses spread, some pilots dismissed them.

Others, after watching a bomber vanish in a tight ring of bursts, suspected that the rumors were true. The first people to feel the difference were not engineers. They were pilots. Oberlot Marcus Han flew a fighter on the Western Front. He had attacked bombers since 1943. He knew Flack. Flack had a rhythm. You learned it. Shells burst too high, too low, too far off. You flew through gaps.

You trusted timing. If the bursts lagged, you dove. If they walked toward you, you turned early. In late 1944, something changed. On a mission toward the Low Countries, his squadron climbed through a familiar band of anti-aircraft fire. Only this time, the bursts felt different. They were not random.

They crowded him. They followed the bombers more closely than before. After the mission in the debriefing hut, another pilot spoke first. “Flack is getting better,” he said. “Too good.” Han shook his head. “Not better,” he replied. “Smarter.” They did not know why.

They only knew that the air around the American formations was becoming a more precise kind of dangerous. Later, when rumors of new fuses spread, some pilots dismissed them. Others, after watching a bomber vanish in a tight ring of bursts, suspected that the rumors were true. Back in Germany, Voke received translated fragments of enemy press and reports.

Some were official, some came from intercepted broadcasts. He read accounts of improved anti-aircraft effectiveness. He saw references to radio fuses and clever shells. The phrase proximity fuse began to appear in their own internal summaries. He added these notes to his file. The pattern was clear enough. Germany had built clever devices, too.

rocket fighters, guided bombs, advanced tanks. But each new design was a strain. Factories had to be retoled, workers retrained, supplies diverted. Every new system felt like a special effort against a shrinking budget. By contrast, the proximity fuse was simply being added to a weapon the Allies already used in enormous numbers. Same guns, new shells, better effect.

In one meeting, a younger officer tried to simplify the discussion. If this fuse is so effective, he said, why not just build a lot of them ourselves? The answer was not emotional. It was numerical. RTOR showed a table. She listed German tube production. She listed radar demands. radio demands, night fighter needs. Then she added a new row.

Fuses, she wrote under it the number required to arm a serious fraction of their flax shells. The numbers did not fit. They could divert tubes from radar, from communications, from existing weapons, but then other systems would fail. They could try to expand factories by late 1944 under bombing, under fuel shortages.

This was not a realistic plan. The Allies had a different baseline. Their electronics industry was large. Their factories were far from enemy bombers. For them, giving each gun dozens of tiny radios was expensive, but possible. For Germany, it was close to impossible without sacrificing other critical systems. The idea could be copied on paper.

The scale could not. In one meeting, a younger officer tried to simplify the discussion. If this fuse is so effective, he said, why not just build a lot of them ourselves? The answer was not emotional. It was numerical. RTOR showed a table. She listed German tube production.

She listed radar demands, radio demands, night fighter needs. Then she added a new row. Fuses, she wrote under it the number required to arm a serious fraction of their flax shells. The numbers did not fit. They could divert tubes from radar, from communications, from existing weapons, but then other systems would fail. They could try to expand factories.

By late 1944, under bombing, under fuel shortages, this was not a realistic plan. The Allies had a different baseline. Their electronics industry was large. Their factories were far from enemy bombers. For them, giving each gun dozens of tiny radios was expensive, but possible.

For Germany, it was close to impossible without sacrificing other critical systems. The idea could be copied on paper. The scale could not. One evening, after most staff had gone, Voke remained in the lab. The disassembled gadget lay in front of him. He had reconstructed part of the circuit. It still looked delicate.

It still looked wasteful by German standards. He turned off the bench light and sat in the half dark. The device meant that the enemy could pack radar principles into something meant to die after a fraction of a second. In his world, radar sets were heavy, important, protected.

Here, the same kind of technology was cheap enough to throw away by the thousands. He understood what that implied. This was not just about better shells. It was about what each side could afford to treat as ordinary. V was not allowed to write openly about defeat. His task was to analyze, not to comment on strategy or politics, but people still talk in corridors, over coffee, in short walks between buildings. In one such moment, Wayabber asked a quiet question.

Do you think he said that this device will win them the war? Vog chose his words carefully. No, he said no single device does that. He paused. But it shows the direction in which the war is already leaning. We use our advanced work to create rare weapons for chosen units. They use theirs to improve weapons for everyone. Vber did not answer. He did not need to.

Both men understood what that meant. In early 1945, Han flew another mission. This time, there were fewer aircraft on his side. Fuel shortages, losses, maintenance delays. He climbed anyway. Below him, he saw more contrails than he wanted to count. American bombers, fighters.

An air war his country could no longer match plane for plane. As they approached the expected flack zone, the formations tightened as usual. Anti-aircraft fire rose to meet them. Now more than ever, Han noticed how often shells burst at just the right distance around the American groups. He did not know about the lab work in Berlin. He did not know about circuit diagrams and production tables.

He only knew that the enemy had found some way to make the sky itself more hostile to any fast, light aircraft trying to get close. He survived that mission. Many did not. To him, the war felt less like a contest of individual machines and more like a slow, steady tilt of the whole environment in the enemy’s favor.

By the time Voke’s report reached higher levels, events on the ground and in the air were already moving faster than paperwork. Cities were burning, fronts were collapsing, units were retreating. In such a context, one more technical warning was easy to file and forget. But if anyone read it carefully, they would have seen a quiet pattern.

The report did not say, “We have lost.” It said in effect, “They can now do routinely what we can only do in special cases, if at all.” That sentence in different words could have been applied to many other systems by 1945. Tanks, trucks, radios, ships, aircraft. The gadget from the bomber was simply a small, precise example of a larger truth. Spring 1945.

The research center did not fall with a dramatic assault. It faded. Staff stopped coming every day. Supplies ran out. Sirens sounded more often. Eventually, someone locked the doors. Files stayed in their cabinets. The disassembled gadget sat in a small box on a shelf. Vog was called to help with lastditch projects. Then he was told to go home.

When Germany surrendered, many such places were visited by new uniforms. Allied investigation teams arrived with lists. They looked for radar sets, rocket plans, jet engines. They seized documents. Some reports were boxed and shipped. Others were copied and left.

It is possible that Vult’s report on the fuse ended up in one of those crates. If so, it joined thousands of pages of similar material from across the Reich. Together, they told a long, complicated story about brilliant ideas and shrinking resources. On the Allied side, the Fuse story was kept quiet during the war. Security rules were strict.

Guns crews were told not to disassemble shells. Pilots were told little beyond the guns are better now. After 1945, details began to emerge. Engineers published memoirs. Declassified reports described the design, the testing, the production.

Readers learned that entire factories had been dedicated to the tiny devices. They learned that each fuse had to survive extreme acceleration when fired, yet still function in the air. They also learned that tens of millions of such fuses had been built. In these accounts, the tone was often proud. The device was presented as one of the small decisive innovations of the war.

For the Allies, the proximity fuse became a successful example of applied science. For engineers like Voke, it had felt very different. To them, the object was not just clever. It was a signal. It signaled that the enemy could link laboratories to mass production in a way Germany increasingly could not. When later historians wrote about the fuse, they often focused on its performance.

how many aircraft it helped bring down, how many rockets it helped destroy. Those numbers matter, but the smaller, quieter moment remains the one in the lab in 1944. A team takes apart a device and realizes we could build this in small numbers. They can build it as standard ammunition. At that point, the gadget becomes less a weapon and more a measurement.

A measurement of industrial depth of distance between two systems. What happened to the people in this story after the war is easier to guess than to prove. Someone like folk would likely have been interviewed by Allied officers. His skills were too valuable to ignore. He might have been asked to explain German radar, missile controls, communications networks.

Later, he could have worked in civilian electronics, radio, television, industrial controls. The same mind that had taken apart a fuse to see how it worked could help design new systems for a shattered economy. RTOR with her mathematics could have found work in education or technical planning.

On the other side, people like Sergeant Ward returned to civilian life. For them, the fuse was one detail in a larger memory of long hours, cold nights, and incoming engines in the dark. Most never saw the inside of the gadgets they fired. They only saw the results. If you step back, this gadget story sounds similar to another pattern we have seen in this same war.

German engineers opened captured tanks. They found no miraculous armor, no secret super metal. They found a design optimized for production, maintenance, and replacement. The real secret was not in one plate or one component, but in the way everything was arranged for scale. The fuse case is similar. The core idea could exist anywhere.

The key difference was who could afford to make it commonplace. Once again, the most important feature was not raw performance in a single test. It was repeatability in thousands of real situations. It is tempting to look for single magic weapons that decide wars. In popular stories, these are bombs, planes, tanks, or secret codes.

In reality, victory and defeat usually grow from slower, less visible trends. The proximity fuse fits both patterns. To the crews who used it, it felt like a dramatic change. More hits, more protection. To the engineers who analyzed it from the wrong side of the front line, it felt like confirmation of an uncomfortable truth. Their country was running out of ways to turn new ideas into mass-roduced tools fast enough.

By the time the gadget reached them, the deeper loss had already happened. Today you can see examples of these fuses in museums. They sit behind glass labeled with dates and technical terms. Visitors pass by. They read a sentence or two. First mass produced proximity fuse. Helped defend cities. Improved anti-aircraft fire. The object itself is not large.

It fits in a hand. It has no obvious drama. No noise, no motion. But if you know what it represents, you can read it as more than a piece of old equipment. You can read it as a sign of what kind of war the world had entered. A war where physics, industry, and logistics tied together so tightly that even a single shell could carry a little piece of a vast system inside it.

The title of this story says that Germany realized they had already lost. That realization did not happen in one dramatic shout or one broken meeting. It happened in moments like the one in that lab. An engineer turns a small glass tube in his fingers. He sees not only what it is, but what it implies.

He sees factories he will never visit, production lines he will never match. He writes a careful report. He does not use the word defeat. He does not have to. The device speaks for him. It says, “If your enemy can afford to use this as a disposable part of ordinary ammunition, then the war is being fought on terms you cannot change with courage or cleverness alone.

” By the time Germany captured that US gadget, the underlying imbalance was already in place. The fuse did not cause that imbalance. It revealed it. And sometimes seeing the truth clearly is its own kind of final blow.