At 0710 in the morning on a humid July day in 1943, the Lake City Ordinance Plant outside Independence, Missouri, was already shaking under the weight of its own machines. Rows of stamping presses, hammered brass into cartridge cups. Heat radiated from annealing furnaces, conveyor belts clattered.

The air carried a metallic smell mixed with oil and sweat. America needed ammunition at a scale no nation had ever attempted. Combat commanders in the Solomons reported burning through hundreds of thousands of rounds in a single week. Infantry units in Sicily demanded more.

Fighter squadrons over Europe emptied their 50 caliber belts so fast that ordinance officers joked it took more ammunition to keep a B7 in the air than to build one. The need was bottomless and the math was unforgiving. Washington estimated that to sustain simultaneous operations in the Pacific and the Mediterranean, the United States needed roughly 2.4 billion rounds every month.

Actual output at that moment was barely half. Inside the factory, 19-year-old Evelyn Carter pushed her cart of brass casings toward line four and tried not to think about the number. Workers whispered about it during coffee breaks. 200 combat reports said the same thing. Frontline units were rationing ammunition, not because of supply lines, but because America simply was not making enough.

Evelyn had started here only 12 weeks earlier, but even she understood the gravity. She watched supervisors frown at production charts pinned to clipboards. She overheard engineers muttering about bottlenecks. She noticed something else, too, something the foreman seemed almost afraid to admit. The most delicate part of the operation, the moment where raw casings had to be fed into alignment tracks before charging and crimping, was still done by human hands, working in a repetitive pattern that had not changed since 1918.

By 0720, a new shift had settled in. Six women gathered at the feeder table, arms moving in tight loops. Pick, place, slide, pick, place, slide. Three motions repeated thousands of times each hour. The plant hoped for 30,000 fed casings every hour on this line, but on most days it stalled at 23,000. The difference when scaled across the entire facility meant millions of missing rounds every 24 hours.

One broken fingernail, one slip, one jammed guide rail, and the entire sequence froze. Evelyn learned quickly that the real enemy inside a wartime plant was not sabotage or defective metal. It was seconds, lost seconds. At 0726, a guide rail snapped loose and a spill of casing scattered across the floor. Production stopped.

A red warning lamp flashed overhead. Supervisors sprinted in. Mechanics pushed carts. The women stepped back, wiping sweat from their foreheads. They knew the drill. Every stoppage meant recalibration. Every recalibration meant lost output. Somewhere in the Pacific, a Marine machine gun crew was firing faster than Lake City could replenish.

Evelyn knelt, gathering the spilled casings, and something odd tugged at her attention. The pattern of the women’s hands, the rhythm, the looping motion of wrists and shoulders. It was circular, predictable, mechanical in its own way. She hesitated watching the motion repeat as the workers resumed.

Pick place, slide, an orbit rather than a line. She should have returned to her cart. Instead, she found herself staring, trying to place the familiarity of the motion. It was on the tip of her mind, a memory from a high school history textbook or maybe a museum trip with her father.

A machine that spun to feed something faster than human hands could ever manage. She tried to shake the thought off. It was absurd. She was no engineer, just a teenager earning 80 cents an hour. And yet, the idea would not leave. A rotating pattern, multiple stations sharing the load, a circular platform that moved items from hand to hand, something that fed endlessly as long as the wheel kept turning.

At 0734, the line resumed at a crawl. Evelyn glanced up at the production clock and felt a tightening in her chest. Another 10 minutes lost, another chunk missing from the daily quota. Somewhere in Washington, a colonel would underline the number in red and call Lake City for explanations. She rose, dusted off her hands, and wheeled her cart down the aisle. But as she walked, the thought came back sharper this time.

A rotating system could eliminate the start stop rhythm of human motion. A wheel, not a line, a ring of feeders instead of a row. Efficiency gained not by forcing workers to move faster, but by letting the machine carry the motion for them. The shape formed in her mind so suddenly that she stopped in the middle of the aisle.

A wheel, a drum, a rotating star of loading slots, like a No, that was ridiculous. But it wasn’t. She remembered the name now. Gatling, the old multi-barreled gun from the Civil War that increased firing rate by rotating barrels instead of demanding one barrel cool down.

What if feeding ammunition worked the same way in reverse? What if rotation could solve the bottleneck that linear motion couldn’t? It was a foolish comparison, she told herself, and yet the idea pulsed with a strange clarity. As she pushed through the heat toward the rear of the factory, she felt the oddest sensation, not inspiration exactly, more like inevitability, as though the solution had been sitting in plain sight, and she had simply tripped over it.

And if she was right, even a modest improvement might ripple outward across the entire plant. A handful of seconds saved at each station. A handful multiplied by hundreds of workers scaled across 12 lines scaled across 24 hours. The numbers could climb quickly, maybe dangerously quickly.

What she did not know yet was how that small observation born in the middle of a jammed assembly line at 0726 would grow into a mechanism capable of doubling Lake City’s daily output. Or how its influence would stretch far beyond Missouri all the way to Normandy Saipan and the skies over Europe. For now all she had was a half-formed idea she barely understood.

But ideas, even fragile ones, shape wars more than we admit. Before we go further, I want to know what you think. If you believe, like I do, that the smallest observations often create the largest shifts in history, comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like. And if you want to see how this idea turns into a machine that changed America’s war output, subscribe so you don’t miss the next chapter. At 0800 hours, the plant whistle screamed again.

in a long metallic blast that rattled the sheet metal walls and signaled the official start of the dayshift. The night crew shuffled out with the holloweyed look of people who had moved brass oil and steel through their hands for 14 hours straight. The day crew moved in, stepping around the bins of warm casings that still emitted a copper smell.

A clipboard hung near the entrance with the morning numbers handwritten in pencil. units short. Again, the deficit looked small on paper. Tens of thousands of rounds, but scaled across 24 hours scaled across the coming invasions, scaled across two oceans. Those missing rounds turned into something far heavier.

Commanders in Europe were reporting firefights where American platoon nearly went black on ammunition. Marine machine gun crews at Munda burned through belts faster than transports could deliver them. The Army’s own quartermaster analysis predicted that if output didn’t rise by at least 20% by autumn, entire offensives might stall for lack of bullets, not tanks, not planes, bullets.

By 0807, the heat had climbed past what most offices would consider survivable. Lake City had been designed for production, not comfort. Long glass windows caught the morning sun and turned the place into a convection chamber. Furnaces warmed the annealing rooms. Steam rose from coolant baths.

Workers wore cotton headbands to keep sweat out of their eyes, but it didn’t help much. Supervisors carried pocket thermometers that routinely showed temperatures pushing 97°. The human body adapted out of necessity, not preference. No one complained. Complaining didn’t add brass to the belts. complaining didn’t move the war a minute closer to ending.

Evelyn pushed her cart toward the main floor and watched the rhythmic sway of moving belts, the endless rattle of trays feeding casings into crimping dyes. Between the noise, the vibration, and the motion, the plant felt alive, restless, almost predatory. America was fighting a war of distance, a war that demanded material over finesse, tonnage, over elegance.

To take a single island in the Pacific, gunners might fire half a million rounds. Destroyer escorts in the Atlantic burned thousands in a single night engagement. A flight of P47 Thunderbolts, those same aircraft that devoured 50 caliber ammunition during bomber escort missions could empty entire belts in mere seconds.

Multiply that by all the squadrons in England, North Africa, the Central Pacific, and the numbers curled upward like smoke. The math was merciless. The front line would always demand more than the factories could comfortably supply. At 0813, a foreman in a sweat darkened shirt unlocked a metal cabinet and pulled out the previous day’s production summary. The line graphs were brutal. Lake City had managed a monthly high of roughly 1.4 billion rounds.

But for the war planners in Washington, that wasn’t just insufficient. It was a crisis. Reports arriving from Sicily said that infantry companies were reducing training fire allotments because they feared they would not have enough for combat.

In the Solomons, platoon leaders wrote home asking families to petition representatives for more ammunition. It sounded absurd, almost melodramatic, but those letters existed. Evelyn had seen photocopies posted on the bulletin board as motivational reminders. A Marine sergeant had scribbled, “We’re running the guns hot enough to melt the jackets. Send more.

She paused near line six as an inspector checked casing dimensions with a micrometer. 12,000 of an inch too wide and the round jammed. 6 th000 too narrow and it failed pressure tests. Precision mattered and precision took time. Time America didn’t have. And yet Evelyn thought even precision wasn’t the real monster here. The real monster was throughput. 1,000 of anything was achievable. 1 million was a challenge. 1 billion per month was something else entirely.

By 0825, the morning briefing began. A lieutenant from the ordinance department read from a typed memo delivered straight from Washington. Consumption rates across all commands had risen by nearly 30%. Enemy resistance was intensifying. More artillery duels, more close-in firefights, more aerial intercepts. Ammunition was disappearing faster than wartime planners had predicted in 1942.

The numbers on the chart looked almost fictional. To support projected operations in Burma, Italy, the Marshals, and soon inevitably, France ordinance plants needed to raise output past 2.4 billion rounds monthly. The lieutenant did not sugarcoat the truth. Failure here meant failure everywhere else.

Evelyn listened, shoulders tensing as he continued. The margin between enough and catastrophe often came down to minutes. 10 minutes lost to a jammed conveyor might not seem disastrous inside the plant, but 10 minutes multiplied across 12 lines multiplied across two shifts multiplied across a 30-day cycle meant hundreds of thousands of rounds simply never existed. And hundreds of thousands mattered.

They were firefights won or lost, hills taken or abandoned, lives protected or spent. She caught herself imagining what a single percentage point of efficiency might look like at scale. A 1% improvement meant roughly 14 million additional rounds per month. A 5% improvement meant 70 million. Numbers so large they barely made sense.

Yet the war ran on them. Logistics officers in the Pacific measured battles not in miles gained, but in tonnage delivered. Aerial commanders calculated sorties by gallons of fuel and belts of ammunition. Behind every frontline success was the quiet hum of places like Lake City places where 19year-olds like her pushed carts of brass under ceilings that dripped with condensation.

At 0833, the briefing ended, and the workers scattered back to their stations. Evelyn hesitated, feeling something she couldn’t quite name, responsibility, maybe, or the faint pressure of a realization forming just outside her awareness. She wasn’t an engineer or a scientist. She had no authority, no title. But she did have eyes. She had noticed patterns others hadn’t.

She kept replaying the looping motion of the feeders from earlier that morning. that circular rhythm, that forgotten memory of a rotating gun mechanism. She felt it again, the sense that the difference between shortage and surplus might not be a matter of heroic breakthroughs, but of the smallest, simplest shift in process.

Before moving on, I want to hear your perspective. If you believe, as I do, that wars are shaped more by production numbers than battlefield tactics, comment the number seven. If you disagree, hit like and stay with this story because the moment where Evelyn’s observation turns into something real is coming and it changes everything.

At 0911 that morning after the briefing dissolved into the usual thunder of machinery, Evelyn stood beside line 4 again and felt the strange insistence of the idea that had been tugging at her since dawn. It pressed at her like a half-remembered dream, something obvious and ridiculous at the same time. The line was running but limping the worker’s motions precise yet strained.

Six pairs of hands repeating the same circular path. The same choreography of fatigue reached lift set withdraw over and over. A loop disguised as a line. She watched for several seconds without blinking, letting the rhythm imprint itself. Then her breath caught. Not because she understood the solution fully, but because she suddenly saw the shape. A wheel, a rotating carrier.

A principle that had existed for nearly 80 years, yet no one here seemed to notice. At 0914, an inspector walked by muttering about throughput again. A missed quota yesterday, another looming today. No one asked why the numbers always lagged. No one questioned whether the bottleneck was built into the process itself.

They simply tried harder. More hands, longer shifts, more pressure. Evelyn wiped her palms on her apron and felt a small pulse of defiance. Trying harder wasn’t going to get Lake City from 1.4 billion rounds to 2 billion per month. Doing the same thing faster didn’t change the math. Changing the motion might.

She slipped away from the line when the foreman turned his back and walked toward a scrap bin near the east wall. It was filled with broken pallets, bent metal brackets, discarded wooden slats, and a dozen objects whose purpose had been forgotten. She picked through the pile, feeling the coarse grain of old pine boards, the rough ends of cut dowels, the cold rim of a discarded bearing ring.

She didn’t know exactly what she needed, but she knew she needed something circular, something that could turn without binding, something that could carry weight but not collapse under vibration. The moment she touched the bearing ring, still oily despite months of neglect, she felt a spark of recognition. A wheel needed a heart. This could be it.

At 0923, she ducked behind a stack of crates near the maintenance shed and began assembling a rough outline on the concrete floor. She arranged three wooden slats in a triangle, then six in a star, then eight. She tested how the slats might rotate around the bearing ring, trying to visualize ammunition casings sitting in small recesses along the edges.

Her fingers trembled from the absurdity of the attempt. She wasn’t supposed to be here. She wasn’t supposed to be inventing anything. She wasn’t even supposed to be away from the feeder station. But the urgency of the idea overpowered any concern for protocol. Time was bleeding away, and so were rounds. She had felt the weight of that deficit all morning.

At 0931, a mechanic emerged from the maintenance shed and froze when he saw her kneeling on the floor with a ring and stray lumber arranged in a strange geometric pattern. He raised an eyebrow. She blurted out what an explanation that even she didn’t fully understand. A conveyor that rotated, a circular motion that redistributed load, a pattern inspired by a multi-barreled gun whose name escaped her at that moment. The mechanic listened, skeptical but amused.

Then he surprised her. He didn’t laugh. Instead, he asked quietly, “What problem are you actually trying to solve?” And when she answered throughput, he nodded. Throughput was a language everyone at Lake City spoke. At 0937, she tried rotating the improvised star by hand. It wobbled. The slats were uneven. The bearing ring slipped free. It didn’t matter. The purpose of the exercise wasn’t to build the final version.

It was to confirm the principal rotational transfer instead of linear transfer, a wheel instead of a conveyor belt, multiple feeders instead of one. Each rotation delivering a fresh set of casings to the alignment channels without forcing human hands into the tight, repetitive, wrist destroying pattern that caused jams.

She measured the approximate diameter with her forearm, 26 in, maybe 28, big enough to carry three trays at once, small enough to fit on the existing framework. At 0942, she went to the small drafting table near the supervisor’s office and drew the rough design with a stub of dull pencil, a central ring, a rotating plate, peripheral slots angled to cradle casings, a mechanical linkage connecting the rotation to the existing conveyor belt motor.

She didn’t know the torque requirements or the exact alignment specs, but she knew the most important variable frequency. If the wheel rotated nine times per minute, each revolution could feed roughly 1,000 casings. Multiply by 60 minutes and the line could exceed 60,000 units per hour. Multiply by four wheels per line and the number ballooned again.

Evelyn blinked, startled by her own calculations. Even modest accuracy would produce gains that supervisors had been begging for since spring. At 0950, the foreman found her and demanded an explanation for why she wasn’t at her station.

She held the paper up her voice, trembling as she explained the concept, a rotating feeder like a gatling gun, but inverted. The foreman stared at her, then at the sketch, then back at her with a look she couldn’t decipher. He didn’t dismiss her. He didn’t scold her. He simply said they would test the model during lunch break, not because he believed it would work, but because desperation had a way of opening doors that were usually sealed shut.

At 0958, she returned to her line hands, shaking mind racing. The machine noise seemed louder now, the rhythm of the feeders more urgent, more fragile. She watched the workers move through their loops and felt a surreal moment of distance as though she were seeing the process through different eyes. She wasn’t imagining the bottleneck anymore. She was diagnosing it.

Even if her wheel failed, even if the mechanics laughed her out of the building, even if the plant reverted to old habits, she had crossed an invisible threshold. Once you see the inefficiency in a system, you cannot unsee it. Before moving on, I want your take on something that historians rarely discuss. Innovation in wartime doesn’t always come from engineers with advanced degrees.

It often comes from people who know the rhythm of a problem better than anyone else. If you agree that familiarity breeds invention, comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like. And if you want to see what happens the first time this crude handbuilt wheel is tested, subscribe so you don’t miss the next part. At 11:22, under the sour smell of coolant and brass dust, the maintenance crew cleared a narrow space beside line two for the test. They did not shut the line down.

No one would dare risk the quota for an experiment dreamed up by a 19-year-old with a sketch on scrap paper. They simply carved out a pocket of floor where a small wooden mockup could spin without injuring anyone if it shattered. A half circle of workers gathered some curious, some skeptical, all exhausted. The foreman glanced at his watch.

The test had exactly 3 minutes, not 4, not 5. Lunch break wasn’t until 12, and the war did not pause to indulge ideas. At 11:23, Evelyn set the crude wooden wheel onto a temporary spindle the mechanic had bolted to a bench. The wheel wobbled before it even turned. The slats were uneven, the bearing ring too loose, but it did not matter.

This was not a prototype. This was proof of motion. The mechanic attached a small belt from a discarded motor. He flicked the switch. The wheel jerked, hesitated, then spun with a trembling, jittery rhythm. Evelyn placed three casings into the shallow recesses she had carved with a pocketk knife. The wheel rotated. One casing fell correctly into the alignment channel. Another bounced out.

The third shot across the bench and clattered onto the concrete floor, spinning like a doomed coin. The workers burst into laughter. Not cruel, just tired, just honest. The wheel was too light, too fast, too uneven. It scattered metal like a toddler tossing marbles. The foreman shook his head and restarted the stopwatch. 2 minutes left.

Evelyn swallowed hard cheeks burning. She adjusted the recesses with her thumb. She slowed the motor by tightening the belt. The second rotation delivered one casing properly and one half jammed. The third bounced out entirely. A pattern was emerging, but not the one she had hoped for. The idea wasn’t wrong.

The build was. And even as failure loomed, she understood that this this moment was where most ideas died, not because they were impossible. Because the first attempt embarrassed the creator. At 11:25, the foreman said time was up. But something unexpected happened. The mechanic who had helped her earlier stepped forward and said, “Wait, one more rotation.

” The foreman let the clock run. The mechanic steadied the wheel with both hands, adjusting the tension, lowering the speed until the rotation resembled the slow, methodical sweep of a lighthouse beam. Evelyn placed three more casings. The wheel turned. One casing fed cleanly. The second slid halfway, but corrected itself at the guide lip. The third wobbled, but fell exactly where it needed to.

A small ripple of surprise moved through the circle of workers. It wasn’t success, not yet, but it was motion that made sense. Motion that could be refined. At 11:26, the foreman cut power. The crowd dispersed. The moment ended. The line roared on, drowning the faint echo of Evelyn’s heartbeat. She helped sweep up the spilled casings, but her mind was far away, racing through variables she barely understood.

depth of recess, angle of approach, damping material, rotational frequency. She felt the strange high of failure that carries instruction, not discouragement. Yet, when she returned to her cart, her hands trembled. The embarrassment lingered. She imagined supervisors mocking her. She imagined engineers dismissing the idea with a single sentence.

If it were useful, someone would have built it already. At 11:35, an older woman from line 4 approached her quietly, the same woman who had patted her shoulder earlier. She said nothing at first. She simply set a casing into Evelyn’s hand and pointed at the faint dent along its rim. “You see that?” she asked. “That’s from fatigue.” “Repetition does that.

” “To metal, to people.” She looked toward the wooden wheel, still sitting crooked on the bench. Anything that reduces that repetition is worth trying. Evelyn nodded, too stunned to speak. She had expected ridicule. She had not expected encouragement. At 11:42, Evelyn slipped away again with her sketch. She sat beside the empty loading dock and began redrawing the design.

Deeper recesses, rubber lining for grip, a weight ring to stabilize rotation, a metal spindle instead of wood. She recalculated the revolutions per minute. She wrote numbers in the margins, crossing them out, rewriting them. Every assumption bent and warped as she tried to imagine a device rugged enough to survive Lake City’s relentless vibration. And then something shifted.

She added a second wheel beside the first, then a third, a staggered rotation, a synchronized triple feed, a system that could act like a mechanical heartbeat. one wheel feeding casings while another reloaded itself. Continuous motion instead of stop start drudgery. Her pulse quickened.

The idea was evolving, expanding into something with weight and teeth. At 11:58, the lunch whistle blew. Workers flooded toward the cafeteria. Evelyn stood stretched her aching legs and stared once again at the factory floor. The lines moved with their usual halting rhythm. The bottleneck remained, and yet she sensed the tiniest tilt in the air. The mechanic had seen possibility.

The older woman had seen necessity. The foreman hadn’t rejected her outright. Failure had not killed the idea. It had revealed its weak points. She walked back toward line two, passing the wooden wheel. It looked pitiful now, fragile and uneven, but she felt a flicker of respect for it. The first draft of anything is a ghost. It exists only to be replaced by its stronger descendant.

Before we move on, I want your reaction. Do you think the first failure of an idea matters less than the courage to refine it? If you agree, comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like. And stay with me because the next stage is where the wheel stops being a sketch and becomes a machine that changes an entire factory.

At 12:47, long after most workers had returned from lunch, and the heat inside the plant had crept back into the unbearable range, the foreman called Evelyn to the supervisor’s platform overlooking the main assembly hall. She climbed the metal stairs with the uneasy feeling of someone expecting reprimand, not recognition.

Below her, the plant roared with its usual chaos. Presses hammering brass into cups, cooling fans, screaming over the furnaces, belts, clattering under the weight of half-finished rounds. But on the platform stood three people who did not belong to the routine of Lake City, a procurement officer from the ordinance department, a plant engineer with grease still on his sleeves, and the mechanic who had helped her steady the shaky wooden wheel. All three were staring at her sketch spread out across the supervisor’s desk and weighted down with

brass casings. At 12:49, the engineer asked her to explain the concept again. She tried stumbling at first, then finding her rhythm. Rotational feed reduced manual transfer, a system that redistributes work stored across a circular motion rather than a linear one. She pointed to her revised drawing with hands that trembled from equal parts fear and adrenaline.

The engineer listened without interrupting, which unnerved her even more. When she finished, he tapped the margin where she had added a second wheel. He asked why. She answered honestly because one wheel could feed continuously only if the next one was already reloading itself. A staggered rotation meant no empty cycles, no pauses, no dead time.

At 12:54, he exchanged a quick glance with the procurement officer, then asked for production numbers, not the plant’s numbers, hers, the one she had scribbled in pencil. She braced for dismissal. Instead, he nodded slowly. Her math was not exact, but it wasn’t fantasy, either.

If a full system ran at nine revolutions per minute with six slots per wheel, and if three wheels were synchronized, the theoretical throughput, approached 100,000 casings per hour. The engineer’s voice flattened into something she had never heard from him before, something like respect, not belief, not yet, but respect for the logic.

Even flawed logic can reveal a path worth testing. At 1300 hours, the procurement officer made a decision Evelyn would only understand fully months later. He authorized the maintenance crew to build a steel prototype during the night shift. Not a production version, just a test rig, something that could spin without disintegrating, something strong enough to hold real ammunition casings without scattering them across the floor.

A test model that could answer the question no one wanted to ask aloud. Could a 19-year-old factory worker actually solve the bottleneck that had haunted Lake City for over a year? At 1308, the rumor reached the assembly floor. Workers leaned over machines to whisper. Supervisors exchanged clipped sentences. The idea of a rotating conveyor was not entirely new.

Factories had experimented with partial rotations before, but a multi-wheel synchronized feed was something else, something untested, something improbable, something that, if it worked, might just push Lake City toward the impossible quota, Washington demanded. The women on line four gave Evelyn quick glances that mixed pride with worry. Pride that someone from the line had gotten this far.

Worry that failure would come down harder on a girl than on an engineer. At 1316, the plant engineer met with line supervisors. He unrolled the blueprint Evelyn had drawn and translated it into engineering language, stabilized central spindle, weighted perimeter ring, rubberlined recesses for noise and vibration suppression, incremental feed into existing alignment channels, gear reduction to control rotational speed.

The supervisors stared, trying to picture the motion. One finally asked the question they were all thinking. What if it jams? The engineer answered with a sentence that stuck in Evelyn’s memory for years. If it jams, we fix it. If it works, we rewrite the rule book. At 13:27, as if to underline the urgency, line six choked again, a jammed guide rail.

A halfozen workers swarmed in, clearing the obstruction, losing another 7 minutes. 7 minutes meant nearly 4,000 casings lost. 4,000 rounds meant entire rifle platoon hollowed out during training or combat. And so the idea of trying something, anything new, began to shift from curiosity to necessity. At 1332, the mechanic handed Evelyn a scrap of steel plate.

He told her the prototype would be built tonight, but if she had adjustments to the design, she needed to make them now. He wasn’t patronizing her. He was inviting her into the process. She took the steel and the newfound responsibility simultaneously feeling the weight of both. She revised the angle of the recesses, deepened the curvature, adjusted the alignment lip. She could not calculate engineering tolerances, but she understood the physics of human motion and how the current system exhausted the workers. The design didn’t need to be perfect.

It needed to relieve that exhaustion. Throughput wasn’t just numbers. Throughput was endurance. At 13:45, the procurement officer called headquarters. A short call, a simple message, a potential improvement in feeder efficiency under evaluation. No mention of who suggested it. No mention of the girl who spent her breaks sketching rotational diagrams on packing paper.

That anonymity might have frustrated someone older, but for Evelyn it felt like protection. Failure would not ruin her name. Success would perhaps reveal it. At 1352, the foreman gathered the workers and gave them an unusual instruction. For the rest of the shift, observe your hands. Observe the rhythm.

Observe the fatigue. He did not explain why. He did not mention the wheel, but he understood something crucial. Innovation lands hardest on those expected to use it. If the workers saw the flaw in the old system, they would embrace the new one without a fight. By 1400 hours, the shift settled into its usual grind, but something intangible had changed. Possibility had entered the building.

A shift supervisor whispered that if this thing worked, it might shave 10 minutes off every hour. Another said it might double output. A mechanic said nothing, but checked the alignment channels with more care than usual. Evelyn watched it all in stunned silence, realizing that an idea born in a moment of spilled casings had now become momentum, and momentum had a way of altering entire landscapes.

Before we move to the prototypes first real trial, I want to hear from you. Do you believe that big war-changing innovations often come from people who were never supposed to innovate at all? If yes, comment the number seven. If not, tap like and stay with this story because the night shift is about to turn sketches into steel and steel into something far more dangerous than anyone expected.

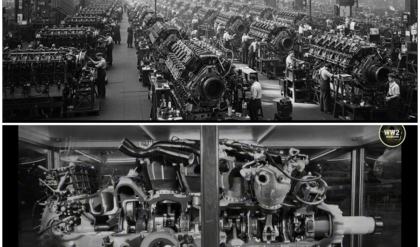

At 1940 that night, long after the dayshift had vanished into the Missouri darkness, the maintenance bay behind line two glowed under harsh white lamps. Sparks showered from welding torches. Steel rang under hammers. The first real prototype, no wood, no wobble, no guesswork took shape on a heavy workbench that smelled of oil and heat.

The night crew had seen countless projects come and go. Most of them minor adjustments, most forgotten within a week, but this one felt different. Not because they believed it would work, because they believed they had run out of alternatives. Production had plateaued.

Washington had stopped asking for improvement and started demanding it. At 1948, the mechanic carefully lowered the new wheel onto a hardened spindle machined only an hour earlier. The plate was nearly 28 in across cut from/4in steel with a stabilizing ring welded around the outer edge. Each slot was lined with rubber scavenged from vehicle tires to absorb vibration. The wheel was heavier than expected, heavy enough that one man could barely lift it without losing his grip.

That weight mattered. In this plant, vibration killed ideas faster than heat. A device that rattled itself apart wouldn’t last 10 minutes on the line. At 1954, the engineer arrived. Coat thrown over his shoulders, clipboard tucked under his arm. He inspected the prototype with the expression of someone trying not to hope too soon.

He adjusted the angle of one recess with a file wiped metal dust from the spindle, then motioned to Evelyn. She stepped forward reluctantly, feeling the eyes of the night crew turned toward her. She wasn’t supposed to be here past her shift. She wasn’t supposed to witness any of this.

Yet here she was, pulled back by the gravity of an idea that had refused to leave her alone since early morning. At 2003, the engineer checked the gear reduction assembly connected to an old motor salvaged from a conveyor line. If the rotation was too fast, the casings would fly too slow and the system would be pointless. He adjusted the tension rod, then stepped back.

Ready, he said quietly. The mechanic flipped the switch. The motor growled. The wheel shuttered once, then began turning in a smooth, steady arc, not perfect, but controlled. A low hum, not a rattling death rattle. The crew exchanged a look. It was working, or at least not failing instantly. At 2006, the first test began. 20 casings placed into the recesses. The wheel rotated.

The casing stayed put. One by one, they reached the feed lip and dropped into the alignment chute exactly as intended. The first 10 fell cleanly. The next few bounced slightly but landed where they needed to. One jammed momentarily, then right at itself. Only one fell outside the chute entirely.

That ratio 19 to1 did not sound revolutionary, but compared to the chaos of the wooden mockup earlier that day, it was staggering. At 2009, the engineer timed the cycle. If this wheel were installed on a line, if it ran continuously, if the feed rate scaled even modestly, the throughput could rise from 23,000 casings per hour to more than 50,000 on a single station.

Multiply that across the line, multiply that across the plant, multiply that across the war. He did the math three times each time with slower breathing. War planners talked about divisions and fleets. But here on this concrete floor, the war reduced itself to casings per hour, rounds per shift, minutes saved, bottlenecks erased.

At 2013, something unexpected happened. A supervisor from the night shift, a man known for mocking anything new, placed his coffee mug on the bench, folded his arms, and simply said, “Again.” They repeated the test and again and again. Different speeds, different quantities, different angles. The wheel behaved consistently, almost stubbornly. It wanted to work.

Even when it faltered, it revealed how to fix the flaw. A deeper recess here, a smoother lip there. No invention arrives fully formed. It fights its way into the world. This one was fighting to stay. At 2027, the engineer ran a stress test. He loaded the wheel with 30 casings, then 40, then 48.

The wheel groaned, the spindle flexed, the rubber lining squealled under pressure, but the system held. Not pretty, not elegant, but functional in the brutal, unforgiving language of wartime manufacturing. Lake City did not need beauty. It needed volume. It needed endurance. It needed something that could turn brass into firepower without bleeding seconds.

At 2032, Evelyn stepped back, barely breathing. She felt something rising in her chest. Not pride exactly, but a quiet astonishment that the idea had survived the day. It was no longer a sketch, no longer a wobbling wooden wheel. It was steel now, weight you could feel, a motion you could trust. And the room sensed it, too. Workers stood a little straighter.

The mechanic wiped his hands on a rag and said nothing, which was as close to praise as anyone would hear from him. Even the engineer’s face, usually locked in fatigue, softened. At 2038, the wheels spun for the final test of the night. 50 casings, continuous rotation. The chute receiving them at a steady, almost hypnotic rhythm.

The sound was different, less like a factory struggling, more like a system breathing evenly for the first time. The engineer exhaled. The mechanic nodded. Evelyn closed her eyes for a second. This wasn’t victory. It wasn’t even success. But it was direction and direction in a war factory was everything. Numbers could rise from here. Production could climb. Quotas could be met.

And somewhere months later, on a beach or a ridgeeline or a jungle trail, a soldier would fire a weapon loaded with ammunition that existed because of this moment. Before we go further, I want your perspective. Do you believe technological breakthroughs are built from hundreds of tiny corrections rather than single moments of genius? If yes, comment the number seven.

If not, taplike. And stay with me because when this wheel is installed on a live line, Lake City’s entire world tilts. At 0650 the next morning, the plant whistle screamed over the parking lot as sunlight cut through the haze above the smoke stacks.

Workers streamed in, unaware that a piece of steel assembled overnight was about to tilt their entire world. Supervisors spoke in clipped tones. Mechanics carried toolboxes with unusual urgency. And at the center of line two, stood the new rotating feeder, bolted into place, polished only enough to keep sharp edges from cutting hands. It looked crude, heavy, overbuilt.

No one would have guessed it might change the trajectory of a factory producing more ammunition than any other plant on the continent. At 0705, the foreman gathered the morning crew. He didn’t give a speech. He simply pointed to the machine and said, “We start slow. If it fails, we shut it down. If it works, you’ll feel it before you see it.

” That sentence hung in the air. Workers stepped closer. Some hopeful, some deeply skeptical. Machines in this place failed all the time. The heat warped metal. The vibration tore bolts loose. Dust infiltrated everything. But the foreman’s tone carried something unusual. Curiosity instead of resignation. At 0711, the engineer opened the motor housing and verified the gear reduction setting.

9 revolutions per minute. No more, no less. Then he nodded at the mechanic. Power. The switch snapped. The feeder wheel stirred, rotated, steadied, and began its slow heartbeat. Not the frantic spin of the wooden mockup, not the trembling imbalance of last night’s first build. A steady, deliberate motion. The workers leaned in.

One fed the first casings onto the recesses. The wheel carried them forward, and then something remarkable happened. Instead of a handful of casings being aligned one by one, the wheel delivered an entire cluster with a rhythm that felt almost unnatural for this plant. No jam, no hesitation, no stop, start stutter.

At 0713, the line ran its first full minute under the new system. The typical feed rate was under 500 casings per minute on this station. That morning, the counter ticked past 700, then 740, then 783. Not perfect, but unmistakable. The increase wasn’t theoretical anymore. It was audible. The alignment channels rattled faster.

The worker’s hands moved with less strain. The entire line seemed to exhale as if someone had loosened a knot in its spine. The foreman didn’t smile, but his eyes narrowed the way a man’s eyes narrow when he realizes a problem he has fought for a year may have just met its match. At 0721, they tested again with a larger batch. The wheel took the load without complaint. Rubber lining absorbed vibration.

Weighted rim stabilized rotation. Casings fell with metronomic consistency that no one could have predicted from a girl’s sketch 12 hours earlier. Supervisors hustled over scribbling numbers. Workers exchanged glances that mixed relief with disbelief. They were used to machines disappointing them. They were not used to machines making their lives easier.

At 0730, Evelyn watched from the side, feeling almost detached from the scene, as if she were watching someone else’s invention take its first steps. She saw things the others didn’t. the slight drift in the wheels axis, the momentary wobble when it hit certain slots, the tiny delay when the chute accumulated too many casings. She mentally logged each flaw. Improvement wasn’t optional.

The war did not reward almost, but for the first time she allowed herself a single slow breath. It worked. Not perfectly, not beautifully, but undeniably. At 0738, the plant engineer pulled her aside and asked the question she had not expected so soon. Could it scale? Could this single wheel become four? Could four become 12? Could the entire line be converted without halting production? She answered honestly, “Yes, but not without redesigning the spindle mounts and strengthening the stabilization ring and reshaping the recess curves.” She

spoke with a clarity that startled even her. The engineer scribbled notes, nodding faster than she could talk. He had seen plenty of promising ideas die under the weight of realworld constraints, but this time, for reasons he could not yet articulate, he believed they were standing on the threshold of something that deserved more than skepticism.

At 0744, as if summoned by fate, the production counter hit an impossible number. A full hour’s worth of output reached a threshold Lake City had never achieved at this hour. 80,000 casings. The workers froze for a moment, staring at the counter as if it were lying. Then the room erupted, not in cheers. This was a war plant after all, but in a kind of stunned electric silence.

A silence that meant everyone understood they had just crossed into new territory. At 0750, the superintendent arrived, pulled straight from his office by the foreman’s urgent call. He studied the wheel, the numbers, the motion of the line, the absence of jams. He looked at Evelyn. The question on his face was the same one the engineer had asked earlier.

Can it scale? And behind that, a second question he did not say aloud. How many lives will this save? By 0800 hours, the wheel had run long enough to prove itself. The superintendent authorized immediate fabrication of three additional units. A full-scale redesign of line two. A phased conversion of the remaining lines if results held for 72 hours.

A memo went to Washington noting an experimental increase in feeder efficiency. No names, no credit, just numbers. The only language wartime bureaucracy trusted. Evelyn descended the platform, feeling the vibration of the floor through her boots. She passed workers who offered small nods, the understated approval of people who recognized when something had shifted beneath their feet.

She moved past the machines, past the bins of casings, past the rows of belts, and felt slowly, tentatively that she belonged here in a way she hadn’t understood yesterday. Not because she had solved a problem fully, but because she had dared to see it clearly. Before we close this chapter, I want your perspective.

Do you believe that wars are won not only by armies, but by factories that learn to think differently? If yes, comment the number seven. If you disagree, tap like. And if you want to see what happens when this innovation spreads through Lake City and pushes American output into territory, no enemy believe possible, subscribe so you don’t miss the conclusion. him.