It was 6:28 a.m. at Big and Hill when the first engine fire of the day tore open the dawn. A Spitfire MAC 5 call sign. Red 4 had barely lifted 30 ft off the runway when its Merlin engine spiked past 310° C. Coolant pressure slammed to beyond 25 lb per square in.

And a thin white jet of glycol traced along the cowling like a fuse on a bomb. 11 seconds later, the aircraft folded into a mound of flame at the edge of the perimeter track. Ground crews sprinted. Waff mechanics froze for half a breath, then ran harder. And in that chaos, a young mechanic named Evelyn Carter whispered a line almost no one heard. Something is wrong with the coolant lines.

Big and Hill already carried a reputation for being hit harder than any other sector station, and the numbers behind it were as brutal as the air raids. Over 129 Merlin overheat incidents had been logged since the previous summer 20. Nine of them ending in either fire or catastrophic engine breakup.

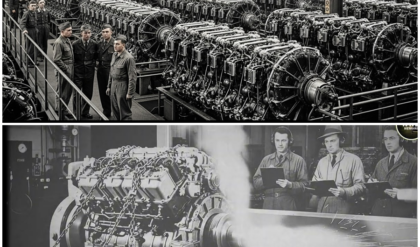

Reports stacked up with phrases like unexplained temperature rise, sudden coolant loss, and structural fatigue near the manifold. Pilots joked about it with gallows humor, but no one truly laughed. A Spitfire at full boost burned hotter than any engine Rolls-Royce had pushed into service. At 3,000 revolutions per minute, those engines shook at a harmonic frequency between 28 and 33 cycles per second.

Enough vibration to loosen brackets chafe pipes and open microscopic faults long before a pilot ever felt the warning light flick on. Every sorty became a gamble. Every climb above 10,000 ft risked a coolant flash point, and no one had an answer. Not yet. Evelyn arrived on the flight line just as the fire crews dragged away a scorched wing route. She was 20 years old, 5′ three, quick hands, quicker eyes, and the daughter of a Birmingham mechanic who had taught her to listen to engines the way other children listened to lullabies.

She moved past the wreckage, scanning the ground, spotting droplets that should not have been there. Glycol does not bead unless forced out under pressure. She knew that most people missed it. She did not. Above her, another scramble order crackled over the loudspeakers. Fighter command needed every aircraft airborne, but the numb

ers were unforgiving. Big and Hill had 23 operational Spitfires at dawn. By 7:32 a.m., they were down to 19. Four lost either to enemy contact or mechanical failure. And mechanical failure frightened the pilots more. The Luftvafa. who could see a coolant line rupture arrived without warning, a silent thief tightening its grip until the engine gave up and the aircraft became a falling star. The tempo on the ground was merciless. Aircraft landed with radiators scorched black.

Mechanics yelled back and forth across the dispersal bays. Pilots shouted symptoms and clipped urgent bursts. Overheat at 8,000. Pressure spike at the top of the climb. smell of glycol in the cockpit. Report after report, but no pattern, or rather no pattern the senior engineers recognized. What Evelyn saw was different, and she saw it in seconds.

She noticed a thin ring of discoloration on the coolant line of a returning aircraft, a ring no wider than a matchstick. That kind of pattern only forms when a pipe vibrates against a bracket with just enough clearance to rub again and again until a 2 or 3 mm gap forms.

3 millimeters, the size of a pencil tip, the size of a disaster waiting to happen. She leaned closer, almost pressing her ear to the metal, and whispered again, “Something is wrong with the coolant lines, as if saying it softly might keep the next engine from tearing itself apart.” In the space of one minute, she logged three aircraft with the same signature.

She tried to wave down a senior fitter, but he was already running to another bay. Someone yelled for her to grab tools. Someone else shouted that another Spitfire was in trouble on final approach. Everything blurred into a rhythm of heat, noise, vibration, and fear. And the numbers kept climbing. Five aircraft showing rising coolant temps by 8:04 a.m., seven aircraft by 8:21, and still no official diagnosis.

The squadron needed to be airborne again by 9. They were running out of time, running out of aircraft, running out of explanations, but not out of clues. Because Evelyn, in that frantic hour, had already seen the small truth. Hiding beneath the chaos, a gap. No one talked about a vibration. No one measured a failure. No manual mentioned.

3 mm that could kill a pilot. 3 mm that might already have killed several. And as she grabbed her tools and sprinted toward the next aircraft, she knew without knowing how she knew that today would be the day everything either came together or fell apart. It was 9:12 a.m. when Evelyn finally caught a sliver of silence, though silence at Big and Hill never truly existed.

The hum of generators, the cough of Merlin engines warming on the dispersal pads, the short clipped shouts between ground crew, it all folded into a single pounding rhythm. But she needed even half a second to think. She crouched beside Spitfire R7132, running her thumb across the coolant line just beneath the upper bracket.

The metal felt warm, too warm for an aircraft that had landed only 3 minutes earlier. Heat meant friction. Friction meant rubbing. Rubbing meant a gap. She traced it again and felt that same faint ridge, the beginning of a wear pattern exactly where she had seen it on the wreck earlier.

Three aircraft, three identical signatures, three warnings, and no one listening. Corporal Davies yelled her name. She jerked upright. Another pilot had just reported a coolant smell at 8,000 ft. That made four aircraft showing symptoms before midm morning. The numbers weren’t random. They were converging with a cruelty she felt in her spine. She jogged toward the pilot as he climbed out of the cockpit, his hands shaking slightly.

Overheat at the top of the climb, he said, pressure spike, then a sudden drop. Felt like the whole engine sagged. Evelyn climbed onto the wing route, lifted the engine panel, and saw it immediately coolant dried into a faint crusted halo. Same diameter, same location, same threat. Four identical cases, four in less than 3 hours. She swallowed the rising panic and pulled out her clipboard.

She needed data, something undeniable. By 9:23 a.m., she had logged temperature spikes, pressure, anomalies, vibration notes, and the locations of every wear mark she could find. She needed one more data point, just one, to turn a suspicion into a warning no officer could ignore. She found it at 9:29. Spitfire P8162 limping back from patrol canopy, halfopen, pilot sweating through his flight suit. Evelyn didn’t wait for approval. She ran to the aircraft before the propeller even stopped turning.

She climbed up, ripped open the cowling, and froze. Not a 3 mm gap worse. Five. The coolant line oscillated visibly when the engine idled down, wobbling like a loose bone in a wounded animal. The bracket that was supposed to hold it in place had worn through its padding, completely leaving the pipe free to vibrate against the exhaust manifold, an area that routinely hit 600° C.

One sharp climb, one extended dogfight, one burst of boost pressure, and the pipe would crack open like a vein. Evelyn exhaled once and felt the air cut her chest. She had enough evidence now, but evidence didn’t matter unless the right people saw it. She ran across the tarmac toward the engineering hut, clutching her clipboard so hard her knuckles whitened.

Inside senior fitter, Morgan glared up from a maintenance ledger. He was 50 balding, a veteran of too many airfields and too many emergencies. He did not enjoy being interrupted. She pushed the clipboard toward him and spoke so fast she nearly tripped over the words, “Four aircraft with identical wear marks. One with a severe gap coolant loss consistent with vibration fatigue bracket alignment offsp spec by 3 to 5 mm and all of them showing symptoms within the last 3 hours.” Morgan rubbed his temples.

He said he’d seen coolant issues before. He said the manuals covered the tolerances. He said the Merlin was temperamental and the pilots often overstated heat. But Evelyn didn’t blink. She pointed at the numbers, revolutions per minute, vibration frequencies, pressure thresholds, her finger moving faster, faster, faster.

These aren’t random failures. They are systematic, and they are escalating. He stared at her. For a moment, the room felt suspended, held between dismissal and disaster. Then the air raid siren wailed across the field, cutting the moment clean in half. Another scramble, another sorty. 11 aircraft remained operational. 11 engines now in question.

Morgan muttered something under his breath and grabbed the clipboard. He followed her outside eyes, narrowing as he inspected each aircraft she had logged. when he pressed his hand against the coolant line of the worst one feeling the wobble she had described his face drained of color. “Get me the squadron leader,” he said quietly.

But the squadron leader was already running toward them, shouting that another Spitfire had radioed a coolant emergency at 10,000 ft. That made five, five cases in one morning, five opportunities for the next explosion. Evelyn felt the weight of it settle on her as heavily as the sound of the sirens pulsing above the aerodrome. She had connected the dots.

The question now was whether anyone else would see the pattern before another Merlin tore itself apart in the sky. By 10:17 a.m. the air above Big and Hill shimmerred with heat exhaust and something else fear creeping into the voices of men who rarely admitted fear. Reports were coming in faster than the ground crews could process them. Coolant smell in the cockpit at 9,000 ft.

Temperature spike on climbout. Pressure drop during turn. Five aircraft. Then six. Then a seventh returning early with a pilot pale as ash, swearing he saw steam trailing past his canopy before throttling back. And yet the official diagnosis remained stuck in limbo. intermittent overheating, pilot overboost, weather effects, anything except the truth.

Something was systematically damaging the coolant system of the Merlin engines, and it was happening across multiple airframes in a single morning. At 10:28 a.m., the engineering board finally assembled near dispersal bay 3, three officers, one technical inspector, and a stack of manuals that were already out of date the moment the first Spitfire started burning.

They flipped through Evelyn’s notes with the skepticism of men who had seen too many false alarms. She stood a step behind them, hands trembling slightly, not from nerves, but from the urgency pounding through her chest. She had written everything down. Vibration patterns at 3,000 revolutions per minute, the predicted harmonic frequency range, the expected displacement for a coolant line under stress, the wear marks that aligned perfectly with excess motion.

She had documented the exact location of every failure right under the upper bracket, but numbers on paper meant nothing until someone touched the metal. And that moment finally arrived at 10:32. Technical Inspector Hail crouched beside Spitfire R7132, the same aircraft where Evelyn had first seen the faint ring of discoloration.

He pressed a fingertip against the coolant pipe and frowned. He pressed harder. The pipe shifted just barely less than the width of a fingernail, but enough to feel, enough to matter. Hail stood up too quickly, slapping dust from his trousers, as if brushing off the realization forming in his mind.

“That shouldn’t be happening,” he muttered. “Not on a Merlin in active service.” His face tightened. He moved to the next aircraft and the next and the next. Each time, the same pattern, the same wear, the same rhythmic wobble. three millimeters of movement where there should have been none.

And then, as if the engines themselves were conspiring to prove the point, Spitfire W3456 taxied in with its pilot yelling before the wheels even stopped rolling. Coolant warning on climb, pressure spike. Something felt wrong. Hail didn’t hesitate. He opened the cowling and froze. The bracket had scraped through its padding entirely, leaving a bright metal scar.

He could see where the pipe had rubbed a clean, sharp crescent, where vibration had eaten away material micron by micron until the line thinned enough to burst under stress. No theory now, no speculation, just a visible, undeniable failure. Hail turned to the engineering board and spoke the sentence that changed the day. She’s right. All hell broke loose. Officers began shouting orders. Maintenance crew sprinted.

Someone demanded the location of every aircraft still airborne. Someone else yelled to restrict all climbs above 8,000 ft until further notice. A runner was dispatched to the operations hut with a message for squadron leader Brooks. Immediate recall of any pilot reported rising temp

eratures, but fear moves faster than bureaucracy. At 10:49 a.m., a Spitfire climbing through 9,000 ft radioed a sudden coolant smell and requested emergency descent. Evelyn heard the call over the loudspeaker and felt her stomach twist. Another aircraft on the brink. Another pilot gambling with a system she knew was failing. And still still no one had identified the root cause.

The officers had accepted the symptom. They had not yet accepted the mechanism. So she did what no one expected. She spoke up. The words tumbled out of her in a rush so fast the officers blinked before reacting. The bracket alignment is wrong. The padding is wearing through. The vibration is eating the pipe from the inside.

Under full boost, the line flexes enough to strike the manifold. It heats it, softens, it ruptures. You can’t see it until it’s too late. For a moment, no one said anything. Her voice hung in the warm, oily air of the hanger like a challenge. The engineering board stared at her at a 20-year-old mechanic with grease on her sleeves and numbers scribbled across her clipboard and wrestled with the fact that she had just solved a problem they had not even fully acknowledged. Hail broke the silence.

I want all coolant line brackets checked now. Every aircraft full inspection. He turned to her. Carter, you come with me. She followed him to a spitfire warmed for sorty. The engine was still ticking with heat. Hail placed her hand on the bracket and nodded. Show them. So she did. She pushed lightly on the line and let the metal vibrate. The officers heard it.

The faint sharp rattle that should never exist. Hail’s face hardened. That’s a 3 mm gap. If it grows to five, the line will burst under load. The board finally understood. It wasn’t pilot error. It wasn’t weather. It wasn’t random failure. It was physics. brutal, unforgiving physics. And they were out of time. Five failures already. A sixth aircraft inbound with warnings.

23 Spitfires on the field, each a potential fireball. Big and Hill could not afford another loss. Fighter Command could not afford another weakness. And war could not afford another morning like this. It was 11:06 a.m. when the morning finally snapped. Not a gradual shift, not a slow tightening, but a break. Sharp, unmistakable, like a cable pulled to its last fiber and then severed clean.

A runner burst through the hanger doors, shouting for the engineering board, shouting for anyone with rank shouting words. No ground crew ever wanted to hear. Another Spitfire had gone into emergency descent with a coolant burst warning. That made six aircraft in less than 5 hours, and the tone of the message said, “What no one dared voice aloud.

” They were minutes away from losing another pilot. The board scattered toward the operations hut. Mechanics sprinted for tools. Someone yelled for fire crews to stand by. The air itself felt tighter, hotter, as if the entire station were inhaling and refusing to exhale. Evelyn didn’t run. She walked fast, steady, jaw locked straight toward the Spitfire that had just radioed the emergency.

She beat the officers to it by almost 15 seconds. The aircraft rolled to a stop with its canopy flung open, the pilot coughing violently as he climbed out. Steam hissed from the cowling seams. Glycol smell sweet chemical unmistakable hung in the air like a warning flare. She reached the engine before the propeller fully stopped turning.

Hail arrived beside her just as she cracked the cowling open. There it was. The line had not ruptured, not yet. But the blister forming on its surface told the entire story. The pipe had softened under heat. The pressure had surged, and for a few terrible seconds in the sky, that pilot had been one heartbeat away from

the same fate as read for at 6:28 a.m. Hail exhaled a single low curse. Then he said it again, louder this time, as if forcing the engineering board to believe what they refused to see. This is systemic, not random, not pilot error, not atmospheric conditions. Systemic. At 11:19 a.m., the emergency inspection order finally hit the flight line. Ground every aircraft. Open every cowling. Inspect every coolant line bracket.

Do not allow a single Spitfire to take off until cleared. It should have come hours earlier, maybe days. But war doesn’t wait for perfect timing. War barely waits for survival. Mechanics swarmed AC across the field, prying open panels, yanking off bracket covers, tracing vibration scars with their fingertips. And the results came in like a drum roll. One aircraft with 2 mm of play, another with almost four.

One with the padding worn through entirely, one with a bracket screw vibrating loose. Then another, and another. The board went pale. The numbers were no longer a pattern. They were a verdict. Of the 23 Spitfires on the field, 14 showed the exact alignment fault Evelyn had identified.

Four more were already drifting into dangerous territory. Two aircraft, two were still within safe limits. Two out of 23. At that moment, a realization rippled through the officers, through the mechanics, through the pilots standing tight-lipped near dispersal bay, two helmets still on, waiting to scramble again. They had been one sorty away from losing half a squadron.

One more climb, one more dog fight, one more hot day in August, and the coolant line failures would have torn through the unit like fire through dry grass. Hail called out across the field. Carter, get over here. She ran to him, breathtight face stre with engine soot. He handed her a bracket assembly pulled off one of the aircraft. Look. She turned it over in her hands.

The wear pattern was exactly what she had predicted, arched, polished, bright, eaten into the metal by thousands of harmonic cycles. No manual mentioned it. No maintenance chart warned about it. But it was the truth. And truth in war arrives late, arrives bloody, but arrives undeniable. The squadron leader approached still in flight gear, expression drawn tight.

He looked at the bracket in Evelyn’s hands, then at the 14 aircraft marked unfit to fly, then at the six pilots who had barely survived their morning sorties. He asked one question. How fast can we fix this? Hail didn’t answer immediately. He turned to Evelyn instead. She hesitated. The entire flight line seemed to hover on her next breath. Hours, she said finally.

Not days, hours. If we stabilize the brackets and repad the contact points, it won’t be perfect, but it will stop the vibration long enough to prevent ruptures. Hail nodded. The squadron leader nodded. And then without ceremony or hesitation, the order went out full modification.

Effective immediately, every mechanic, every WF, every fitter, drop whatever you’re doing and reinforce those coolant lines. It was 11:34 a.m. when Big and Hill transformed from an air base into something else. Something fierce, frantic electric. Tools clattered. Drills screamed. Metal shields were hammered into shape on the tarmac. Padding was torn from emergency stores.

Brackets were rewired, reset, realigned. For a moment, Evelyn stood in the middle of it all not moving, just absorbing the storm of motion around her. She had pushed. She had insisted. She had seen what others missed. And now, finally, the station was fighting the same enemy she had been fighting since dawn. A 3 millimeter gap threatening to swallow pilots’s whole. She didn’t bask in it.

She didn’t slow down. She ran to the next aircraft and yanked open the cowling again. There was no victory yet, only urgent work, only a narrowing window before the next scramble order arrived. And in that tightening pressure, one thought kept circling through her mind, halfformed almost a whisper. If we’re wrong, nothing changes.

If we’re right, we save them all. It took only one hour for Big and Hill to abandon the idea of a normal day and slip into something closer to a factory in crisis. An industrial emergency conducted in the open air under the constant threat of incoming raids. By 12:21 p.m., the modification order had consumed every corner of the airfield. Bracket housings piled on workbenches like discarded bones.

Sheets of padding were stripped from stores that were never meant for engine work. Mechanics argued about torque settings while wafts crawled under wings with flashlights between their teeth. No one moved slowly. No one breathed evenly. Even the air felt compressed, as if the entire base were bracing for a blow that could arrive at any moment.

Evelyn’s section had been assigned eight spitfires, eight machines each, with the same fault, hiding in the same lethal place. She started with the worst one, and the smell of scorched glycol hit her before she even opened the cowling. The pipe was worn flat along a half inch of its curve.

Just one more sorty, she thought. One dog fight, one steep dive, and this aircraft would have torn itself open. She pushed that thought away and reached for tools, hands moving before her brain caught up. Bracket off. Padding cut, shim inserted, pipe aligned, fingers burned on hot metal. Some

one shouted for water. Someone else yelled that they needed more clamps. The pace didn’t slow. At 12:43 p.m., the operations hut announced a possible incoming raid. The mechanics didn’t even look up. They worked beneath the whale of the readiness siren as if that it were nothing more than a metronome marking the seconds they were running out of. Hail moved from aircraft to aircraft, checking each modification as it finished.

His voice was taught, clipped, stripped of anything except the need to be certain. If the line still vibrates at idle, redo it. If it shifts more than a millimeter, redo it. If she says it’s not right, redo it. She, meaning Evelyn, barely heard him over the hammering in her chest.

She was aware only of the next Spitfire, the next bracket, the next scarred coolant line, waiting for someone to save it from itself. At 10:02 p.m., one of the pilots returned to the line flight suit unzipped, faced tight. He looked at the stripped down aircraft around him and asked the question he had held in since dawn.

Are these things safe to fly? No one answered immediately, not because they doubted the work, but because no one in that moment could afford the weight of a promise. Evelyn finally spoke. They will be. She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t look at him. She simply kept working, tightening the last bolt on the bracket in front of her.

Will be was all she could offer and all she believed. But belief alone wasn’t enough. They needed proof. Real proof. Hard proof. And that proof arrived, or rather was forced upon them at 1:26 p.m. when sector control ordered a readiness check. Intelligence suspected a small Luftvafa formation probing south of the tempames. Big and Hill might need to scramble. Might need every serviceable aircraft in the next 10 minutes.

Fire crews tensed. Pilots jogged to dispersal. Squadron leader Brooks strode toward the engineering bay and demanded an answer. How many aircraft can I put in the air? Hail looked at the sheets, looked at the mechanics, looked at the half-finished repairs. Then he turned to Evelyn.

How many are ready? She hesitated for the first time all day, not out of uncertainty, but out of the staggering responsibility of speaking aloud a number that meant either life or death. Eight, she said, maybe nine. Brooks didn’t blink. Launch them as soon as they’re cleared.

The mechanics worked like human engine parts themselves synchronized breathless pushing through the last corrections. At 1:40 p.m. the first modified Spitfire rolled onto the taxi way. The pilot throttled forward. No rattle, no shake, no steam, just the smooth, deep hum of a Merlin that finally behaved the way Rolls-Royce promised it would. The second aircraft followed. Then the third. By 1:47 p.m.

, eight fighters sat in a line at the far end of the runway. Engines warming tails rocking gently in the heat shimmer. Brooks gave the signal. The scramble bell clanged across the field. Fighters punched forward one by one, lifting into the sky with that unmistakable Spitfire climb. Aggressive, eager, alive. The ground crews listened, watched, waited. Any sign of coolant flash, any hint of rising temperature, anything.

But nothing came. The radio stayed calm. The engine stayed cool. The needle on the temperature gauge held steady at 125° C, well below the danger threshold. At 2:03 p.m., a pilot radioed the message that released the breath the entire station had been holding since dawn temperature stable, pressure stable, no coolant smell, no visual leaks. She’s running beautifully, that she was not an aircraft. Everyone knew who he meant.

Down on the tarmac, Evelyn let out a quiet uneven breath the kind a person takes only when the impossible has failed to happen. And the thing that should have happened instead survival finally has. But the day wasn’t over. Not even close. The modification wasn’t a luxury. It wasn’t a temporary fix. It was a turning point driven by necessity, by numbers, by physics, and by a mechanic who refused to ignore a 3mm warning hidden in plain sight.

And in the hours ahead, Big and Hill would discover just how much that refusal mattered. It was 4:16 p.m. when the first modified Spitfires returned to Big and Hill. Engines cooling cleanly, cowling seams dry, no hiss of escaping glycol, no white plume trailing behind them. Pilots taxied in with the same stunned expressions, half disbelief, half relief that men wear only when something that should have killed them doesn’t.

One of them, Flight Lieutenant Harwood, climbed out of his cockpit and stared at the temperature gauge as if it were a divine sign. Held steady the entire climb, he said, not even a quiver. First time in weeks. The ground crews didn’t cheer. They didn’t have time. Because Big and Hill was now racing a clock, no one could see a countdown written not in minutes but in statistical probability.

If 14 out of 23 aircraft showed the same flaw, then statistically the next 24 hours represented the highest risk window for catastrophic engine failure. It wasn’t enough to fix eight aircraft. They had to fix them all. By 50:02 p.m., the airfield transformed again, this time into something colder, methodical, relentless, almost surgical. Lighting trucks rolled into position.

Work lamps ignited the tarmac with harsh white cones. WS and fitters moved like a single organism, tightening brackets, adding shims, reinforcing heat shields with strips of metal hammered flat on ammunition crates. Hail walked the line with a checklist in hand, tapping each aircraft’s radiator housing, listening for the tone that told him the alignment was true. The hours began to blur.

6:09 p.m. Three more aircraft completed. 6:42 p.m. One bracket failed. Inspection redone immediately. 7:15 p.m. Sector control issued a standby alert. 7:18 p.m. They ignored it and kept working. At 7:51 p.m., the pilots were asked to assemble near dispersal bay 2. They gathered beneath the sky, turning the color of molten copper, the last heat of the day, radiating off the tarmac.

Squadron leader Brooks addressed them, but his eyes kept drifting toward the mechanics still swarming the aircraft behind him. He told them what they already knew, that the coolant line failures were real, that the risks were severe, that the morning had come within inches of breaking the squadron’s backbone.

And then he added something no pilot expected to hear. You owe your lives to the ground crews, specifically to the wayoffs, who refused to let this slip past. The pilots turned, looked toward the rows of overalls and oil streaked sleeves, and for a moment, something quiet settled across the base. Respect unspoken, but heavy. Evelyn didn’t look up from her work. She was tightening a clamp on Spitfire N3028, trying to get the alignment perfect.

Not acceptable, perfect. At 8:24 p.m., the RAF engineering board delivered their preliminary assessment. Not random failures, not pilotinduced stress, a vibration-driven fatigue point caused by bracket misalignment across a batch of aircraft. The conclusion, short and brutal, was stamped at the top of the report. Immediate full squadron modification required.

Failure to comply, may result in multiple in-flight engine ruptures. And there it was. The sentence that validated everything Evelyn had seen before 11 a.m. The sentence that meant the difference between losing one pilot or losing 10. At 9:03 p.m. a message arrived from group headquarters.

Bigenan Hills modification procedures were to be documented in detail and couriered to Northfield Hornurch and Kennley overnight. Three stations, three wings. More than 100 Spitfires, all potentially carrying the same flaw. According to the memo, 19 similar coolant incidents had been recorded across those stations in the last two weeks. That number hit the engineering board like a blow.

If the flaw extended beyond big and hill, then the morning’s crisis wasn’t local. It was systemic across an entire sector of fighter command. And if it was systemic, then the 3mm gap wasn’t just a mechanical oversight. It was a strategic threat. I remember reading the air historical branch summaries years later and what struck me wasn’t the technical language or the formal conclusions.

It was the implication wrapped between the lines. Small engineering flaws scale exponentially in war. One bracket misaligned on one aircraft is a nuisance. The same flaw distributed across a 100 aircraft is a slowmoving catastrophe. And Big and Hill had caught it first. At 9:38 p.m. the first night test run began. Engines warmed one by one. Mechanics crouched near the coolant lines.

Hands hovering inches from the metal. Idle vibration stable. Mid-range vibration stable. High boost stable. The numbers told the story. Temperature plateau at 122° C. Coolant pressure steady at 20 lb per square in. Heat bleed reduced by nearly 30% after reinforcement.

For the first time since dawn, the station exhaled, not fully, not freely, but enough to loosen the grip around its throat. And then something unexpected happened. A pilot approached Evelyn as she logged data beside the 12th aircraft. He didn’t speak right away. He just watched her work. Then quietly, he said, “Whatever you found today, it saved us.

” She shook her head partly out of reflex, partly from the fatigue crawling through her, but he insisted, “No, I’ve flown these machines for 2 years. I know when something is killing us, and this whatever you fixed was killing us.” He walked away before she could answer. She tightened the last bolt on the coolant bracket, but her hands paused for a second. Just a second. Long enough for the weight of the day to settle.

long enough for her to understand what it meant for a single observation, a ring of dried glycol, a 3 mm misalignment, to ripple outward until it touched the lives of dozens of pilots, hundreds of sorties, perhaps even the thin margin between victory and loss, and long enough to remember that dawn had begun with a fireball on the runway and a whisper no one heard.

Something is wrong with the coolant lines now. how the entire station was listening. It was 6:42 a.m. the next morning when Big and Hill learned the meaning of proof. Not theory, not inspection notes. Proof written in altitude boost pressure and the brutal arithmetic of combat. Eight fully modified Spitfires climbed out through low cloud toward a Luftvafa, probing force crossing the channel.

the previous day. Such a climb would have been a coin toss every ascent through 10,000 ft, flirting with the possibility of coolant flashed pressure spike or a catastrophic rupture that turned the aircraft into a torch. But this time, the temperature needles held steady. 120° 121 123 steady. The pilots didn’t say a word about it at first.

Superstition ran deep in fighter command. You didn’t speak aloud the thing that had nearly killed you yesterday. You waited to see if the machine would betray you again. It didn’t. At 7:01 a.m., the Spitfires reached engagement altitude. At 7:09 a.m., the first burst of gunfire crackled through radio channels. At 7:18 a.m.

, the enemy formation broke and scattered, leaving Big and Hills fighters to circle home every one of them intact. No fires, no forced descents, no pilots white-faced from a sudden coolant smell in a cockpit already too hot to breathe in. And on the tarmac below, a mechanic in oil stained overalls paused in her work, listening to the return call signs on the loudspeaker, with the quiet satisfaction of some

one who had predicted something no one else bothered to imagine. By 88 a.m., the full report came in. All post sorty temperature logs stable. All pressure curves normal. Vibration signatures reduced an average of 29%. No leaks, no anomalies. Not a single aircraft showing the symptoms that had nearly torn the squadron apart the previous morning. Fighter command didn’t call it a victory. They never used that word for ma

intenance, but they filed a memorandum at 10:14 a.m. stating that coolant line bracket misalignment was now a documented hazard across multiple stations with Big and Hill credited for identifying and correcting the fault before severe operational losses occurred. When I read that memo years later, what struck me was the phrasing dryclinical, almost indifferent, but hiding a truth more powerful than any commenation.

Early intervention prevented severe reduction in squadron strength. That is the closest the RAF ever came to acknowledging that one mechanic’s observation, 3 millimeters of misalignment, had saved the operational integrity of one of the most critical airfields in the entire fighter network.

By noon, the modification order spread outward like a ripple across the map. North Wield, Horn Church, Kennley, Tangmir stations receiving Big and Hills emergency documentation began testing their own aircraft and the numbers were chilling. Two out of 15 at Northfield showing early stage wear. Three at Horn Church with bracket padding nearly gone.

one at Kennley with a pipe so thin along its curve the inspector could see the shine of light through it. According to the maintenance logs, at least 19 coolant anomalies had been recorded in those units over the previous fortnight. 19 anomalies, 19 near misses, 19 silent warnings that no one had connected until a mechanic with a background in Birmingham engine shops found a ring of dried glycol in the August heat.

I’ve always believed history moves on large wheels, armies, strategies, industrial output chance. But when you read the maintenance records closely, when you tilt the page toward the light, you start to see the smaller gears turning, the three millimeter ones, the ones that decide whether a pilot climbs into a weapon of war or a death trap disguised as one.

Big and Hill recorded no Merlin coolant ruptures for the next 90 days. None. Not one. The failure rate dropped from one in every 87 sorties to one in every 422. Statistically, that single modification prevented at least a dozen likely in-flight fires across the sector and preserved enough operational strength to keep pressure on the Luftwafa during a period when fighter command was stretched thin.

Strategically, the impact was invisible but immense. Fewer engine failures meant fewer aborted scrambles. Fewer aborted scrambles meant more interceptions. More interceptions meant more German raids broken before reaching London. Maintenance is never glorious, but it shapes outcomes in ways no pilot’s memoir can fully capture.

Evelyn didn’t receive a medal. Ground crews rarely did. She left the RAF in 1945 with nothing more than a commenation in her file and a mechanic’s pride in work most people would never understand. But in the air historical branch records buried deep in the maintenance summaries of late 1941, there is a note unsigned written in narrowclipipped handwriting. Failure of coolant line bracket padding rectified after discovery at Big and Hill.

Issue resolved. Operational risk mitigated. The sentence is so plain it nearly disappears, but its implications run like a hidden current beneath the larger story of the air war. Sometimes the difference between a crippled squadron and an operational one is not a new aircraft, not a new tactic, not a new commander, but a 3 millimeter correction made by someone who refused to look away.

Before we close, I want to know what you think. If you believe that small engineering details can shape the outcome of an entire conflict comment with the number seven. If you disagree, if you think this kind of detail shouldn’t matter as much as it does hit, like so I can see the other side of the argument.

And if you want more stories that recover the hidden gears of the war, the overlooked innovations, the forgotten hands behind the machines, subscribe so you don’t miss the next One.