At 0728 a.m. on a frozen morning in early January 1945, the artillery crews of the American 94th Infantry Division watched the tree line in front of them shutter as 14,000 German troops pushed through the fog. They had less than 1 minute to react. Not 60 seconds in theory, but an actual window closer to 53 seconds before the German advance smashed into their forward line. And the truth was brutal.

Before this day, before this moment, the American guns in this sector had a probability of kill so low it was essentially a rounding error. Traditional contact fuses meant you had to hit the target directly, not near it, not around it, directly.

At these ranges against moving troops in a blizzard, that meant one effective hit for every thousands of shells fired. In 1942, the combined American and British air defense forces routinely fired 2500 rounds to bring down a single enemy aircraft. That number is not a dramatic exaggeration. It is an official figure. And now these same principles, these same obsolete fuses were all that separated the American line from collapse.

Then the first shells detonated, not on the ground, but above it, 6 to 10 meters in the air, exactly where the fragments would shred the packed German formations. The explosions looked wrong. They sounded wrong. They burst in midair like invisible hands, snapping the sky open, and the German assault staggered.

In 15 minutes, the American battalion fired 200 rounds and shattered an attack that should have overrun them. The officers on the ground did not know it. The German commanders did not know it. Most of the United States Army did not know it. But this was the first large-scale battlefield use of an invention the military had treated as a fantasy only a few years earlier. A fuse that could sense when it was near a target.

A fuse that could turn a dumb artillery shell into something terrifyingly close to intelligent. A fuse built around electronics so fragile the Navy once believed the idea was impossible. A fuse that had been tested through more than 100,000 hours of laboratory work. And the key improvements that made it viable came from the hands of people the history books never mention.

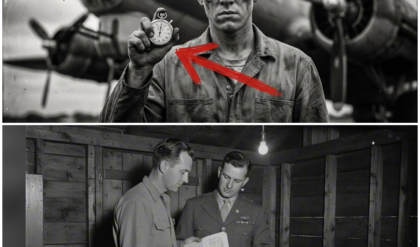

A young woman in a windowless workshop in Maryland had spent her nights soldering vacuum tubes no larger than a thimble. Tubes that had to survive 20,000 gs of acceleration the moment the shell left the barrel. tubes that had to measure distance in micros secondsonds while being slammed forward at the speed of sound.

She was not designing strategy. She was not standing on a battlefield. She was fixing microscopic flaws that made the difference between a shell that exploded harmlessly and a shell that destroyed an entire wave of attackers. And the astonishing thing is this. Without her and without the other women whose hands assembled, calibrated, tested, and retested the proximity fuse, the United States would not have possessed this weapon in time for the Ardens or London’s fight against the V1 or the Pacific campaign where kamicazi attacks nearly broke the fleet. But we start here in Belgium because the contrast is

so violent. Artillery that once killed almost nothing now performed with an effectiveness jump of nearly 900%. A weapon that had taken over 3,000 shots to down an aircraft now could do the same job in 50. Numbers like this hit the brain strangely. They feel wrong because they are too large.

Yet they are real. They are archived. They are measured in afteraction reports where officers admitted they did not understand what had happened that morning. They just knew the air above the German troops seemed to erupt with perfect timing. And here is the quiet twist. The woman who helped to make that timing possible was not on any battlefield. She never saw the Arden.

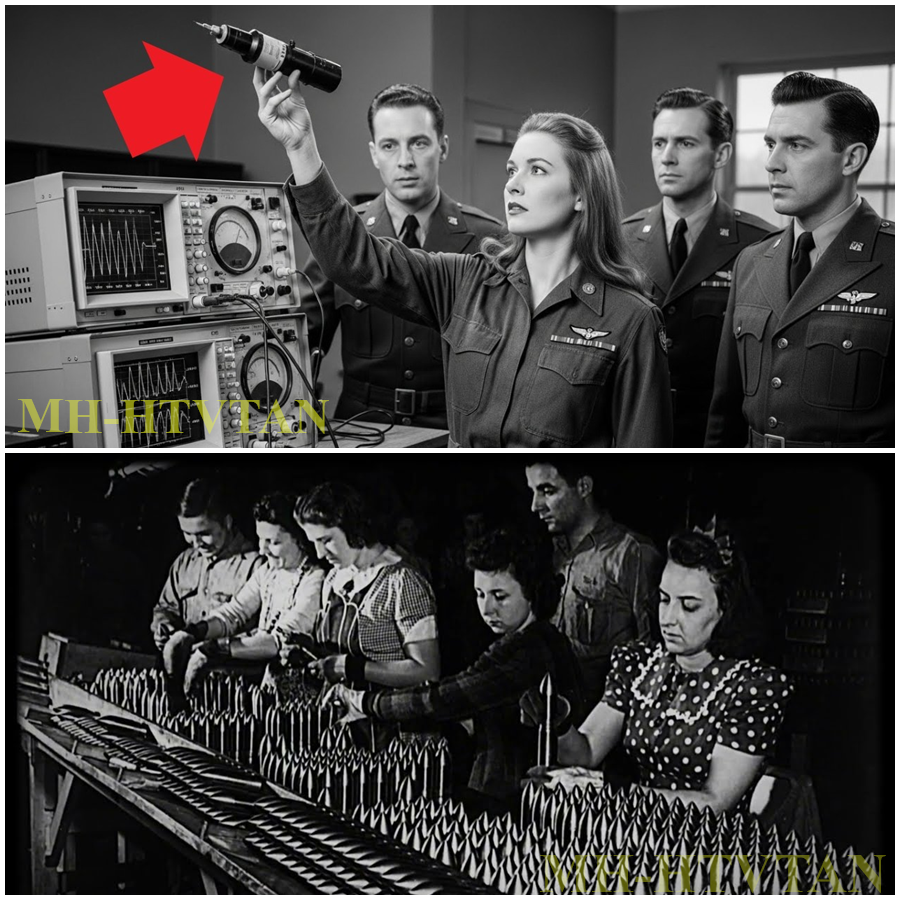

She never watched a single V1 explode in the dawn sky over London. She simply sat in a lab at 2:18 a.m. on a winter morning, studying a vibration trace on an oscilloscope, realizing that the internal coil of the fuse shifted less than 12th of a millimeter under shock.

and that tiny shift caused premature detonation. Her correction, an adjustment few people would have noticed, allowed the fuse to survive launch and arm itself at exactly the right moment. From the documents I have read, I believe this is one of the clearest examples of how modern war turns on details no larger than a grain of sand. No dramatic heroics, no last stands, just precision.

and the will of a woman refusing to accept a 1% failure rate because she understood that a 1% failure rate multiplied across millions of shells meant thousands of dead soldiers. If you believe a small technical detail can decide the fate of an entire battle, type the number seven in the comments. If you disagree, hit like instead. And before we continue, subscribe to the channel if you want more untold stories like this.

Before the proximity fuse existed, before anyone imagined a shell that could think the United States and Britain were losing a very specific kind of war, not on the ground where tanks clashed, not in the skies where fighters duled, but in the invisible space between gun barrels and their targets. A space where physics did not forgive mistakes.

The truth buried in reports from 1940 through 1942 is cold. anti-aircraft fire barely worked. In fact, when analysts calculated effectiveness across the entire Royal Air Force and American Coastal Commands, they found kill probabilities so low they bordered on statistical noise. One confirmed hit for every 2,000 to 3,000 shells fired that meant city’s fleet supply lines entire theaters of war were defended by weapons that were mathematically incapable of providing meaningful protection.

At 0850 a.m. on June 4th, 1942, during early Pacific operations, the USS Yorktown logged an incident where 59 rounds of 90 mm fire were directed at a bomber approaching from port. All 59 missed. Days later, the same bombardier in a captured report admitted he flew through American flack with almost no fear because detonation timing was consistently wrong by 30 to 40 m. It wasn’t that American gunners were unskilled.

It was that their fuses were identical in principle to the ones their fathers had used in 1918. A metallic cap designed to explode only on contact. And in a world where aircraft move faster than ever recorded, that idea collapsed. You could not rely on hits.

So the idea of a fuse that detonated when merely near a target became not simply desirable, but mandatory. And yet the scientific problem was cruel. A fuse small enough to fit into the nose of a 5-in diameter shell, robust enough to survive 20,000 gs and smart enough to detect a passing aircraft within micros seconds was, according to a senior Navy scientist in 1941, physically improbable. Those were his exact words, physically improbable.

But physically improbable did not matter because strategically impossible was worse. Britain was being attacked by YV1 flying bombs at more than 350 mph. Germany was preparing larger raids against London. In the Pacific, the United States lost more than 40 ships in the first half year alone.

And projections written that September warned that without advances in air defense technology, the fleet might not withstand another 12 months of highintensity kamicazi style operations. When I read those documents, the thing that strikes me is how desperate the tone becomes. The problem was not tactical. It was mathematical. You could fire more guns, train more crews, build more ammunition, and the kill rate would stay the same because the limiting factor was the fuse itself.

It was like trying to fight a modern war with 19th century timing. By mid 1942, military planners finally confronted the truth. The only path forward required electronics. Tiny vacuum tubes, miniature circuits carefully shielded coils components sensitive enough to detect reflected radio waves and durable enough to survive a launch shock that shattered most equipment on impact.

And the only workforce in the United States with hands steady enough to assemble and calibrate these components at the scale required was the rapidly expanding core of women technicians entering laboratories and production lines. Again, this part is rarely mentioned in summary histories, but internal correspondents from the Bureau of Ordinance makes clear that female precision workers consistently had lower assembly error rates on micro components.

They were not supplemental labor. They were the only feasible labor for the most delicate stages of proximity fuse production. This changes the narrative entirely. The war was not only running out of men, it was running out of time for old technologies. And the idea that the allies might lose critical battles because an artillery shell detonated too late or not at all is in my view one of the least appreciated strategic threats of the early 1940s.

So when the proximity fuse research effort began, it was not treated as a hopeful experiment. It was treated as a survival requirement, a last chance to drag anti-aircraft fire into the modern era. The stakes were so high that by November 1942, the Allies classified the project above even radar developments.

If captured, the Germans could reverse engineer it in months. If leaked, the entire advantage would disappear. It is in this context that the woman from section T stepped into her role. She wasn’t filling a vacancy. She was joining a fire brigade in a burning house. Every correction she made, every misaligned coil she fixed, every cracked tube she rejected, translated directly into the gap between thousands of shells that failed and a few hundred that might finally work.

And in the language of war, especially in the language of 1944 and 1945, that gap was the difference between a defended city and a destroyed one. If you agree that wars are often lost not by armies but by outdated technology type, the number seven in the comments. If you don’t agree, tap like instead and subscribe if you want more stories hidden behind the official version of World War II. By the time

she walked into the laboratory at 0640 a.m. on a gray winter morning in 1943, the project had already consumed millions of dollars, tens of thousands of man-h hours, and the patience of nearly every senior scientist supervising it. But none of that mattered to her. What mattered was the tray of unfinished fuses on her bench. Each one a tiny metal cylinder no longer than her thumb, each hiding an electronic heart that had to survive forces no living person had ever experienced.

Before she even removed her coat, she leaned over the inspection lamp, switched it on, and started checking the first vacuum tube. The lab was freezing. The heating system had failed again. She didn’t care. Most of the people on the project didn’t even know what the fuse actually did. She did, and that knowledge carried a weight.

Her official role was ordinary quality control technician, a title as bland as a filing cabinet, but inside section Titles meant nothing. What mattered was precision. Her hands were steady, unnervingly steady. And that steadiness was why she had been pulled out of a factory line and placed here in a locked building guarded around the clock where windows were painted black and every scrap of paper had to be burned before leaving the facility.

The moment she arrived, a senior engineer placed four failed units in front of her and said quietly, “These detonated too early. Find out why.” She worked silently at first, sliding the jeweler’s loop over her eye, adjusting the bench lamp, rotating the fuse to catch the angle of the solder. The flaw was microscopic, a strain crack in a filament less than 120th of a millimeter long. Under normal circumstances, such a crack would mean nothing.

But under 20,000 gs, it became a death sentence. The filament snapped, voltage spiked, the circuit triggered prematurely, and the shell blew apart in the gun tube. One microscopic fracture multiplied across thousands of fuses meant dead gunners. She tightened her grip on the magnifier. This wasn’t theory. This wasn’t academic.

It was the lives of men she would never meet. Around 09:15 a.m., a junior officer rushed into the lab holding a report from the Aberdine proving ground. Another test had failed. A full batch of fuses detonated before arming. The room fell silent. She slowly removed her loop, took the report, and read it twice.

According to the test graph, the failure occurred exactly 6 milliseconds after launch. 6 milliseconds. That time slice stuck in her mind like a hook. She whispered it to herself six milliseconds, then sat back down at the bench and opened a fresh unit. While the oscilloscopes hummed, she ran a mental calculation that even she didn’t fully understand in words, only in instinct.

If a fuse needed 6 to 7 milliseconds to arm, then any internal vibration crossing a threshold during that window would ruin everything. Her job wasn’t to design the circuit. Her job was to eliminate the tiny betrayals of physics that caused it to collapse. As she lifted another vacuum tube, something clicked. The coil placement, not the coil itself, the distance between the coil and the inner wall of the fuse body.

A distance so small that a casual inspector would never see it, but she saw it. because she had spent months staring at these devices, memorizing the way metal reflected under the lamp, the way solder pulled when cooling unevenly, the way a tube felt when it was even slightly misaligned. I remember reading a declassified memorandum about this exact phase of the program.

And what struck me something the dry language of the document could not hide was how personal this work was, how human. The science was rigorous, yes, but the success depended on intuition sharpened by repetition. And in my view, this is the part our standard retellings always miss. The breakthrough didn’t come from a blackboard or a formula.

It came from a woman who understood the difference between almost correct and absolutely correct. Late that night at 2:17 a.m., she finally confirmed it. The coil had drifted during assembly because the supporting epoxy cured unevenly at low temperature. The fix was simple. Warm the epoxy. Test each alignment.

Rebuild the entire batch. When she delivered her report the next morning, the chief engineer didn’t say a word. He just stared at her notes, not at once, and quietly ordered 500 new units built under her revised procedure. If you believe stories like this show how wars are won not by glory, but by people who refuse to accept small errors, type the number seven in the comments.

If you don’t think such moments matter, tap like instead and subscribe for more episodes that reveal the hidden mechanics of history. By 0753 a.m. the next morning, the test range at the proving ground was already shaking from repeated firing. Shell after shell slammed into the cold air disappearing in seconds, each one carrying a fuse assembled under her revised procedure.

Engineers watched from behind armored glass. Some took notes. Others simply held their breath. They had seen too many failures over the past year to trust anything. And on the first shot, nothing changed. The shell detonated too early. A flash of white in the wrong place. A groan rolled through the observation room.

Second shot, same result. Third shot, premature detonation again. Someone swore under their breath. The chief engineer tightened his jaw. She didn’t react. She kept her eyes on the oscilloscope trace being printed in the adjacent booth. Only after the fifth shot did she lean closer. The spike was different, not fixed, not random

either, moving. At 08:22 a.m., she stepped out of the booth and requested the raw vibration logs. The officer on duty hesitated. No one ever asked for these. They were massive dents, nearly unreadable. But she took them, spread the sheets across the metal table, and traced a finger down each column. The shells weren’t failing for the same reason as before.

The misalignment she corrected was no longer the issue. Something else had emerged. a resonance pattern just after launch. A secondary vibration spike at 2.1 milliseconds, strong enough to destabilize the arming circuit. She closed her eyes. That was the missing variable. A phenomenon buried so deep in the process that most teams had shrugged and blamed manufacturing defects.

The chief engineer approached. “Is this another coil issue?” She shook her head. “No,” she said quietly. It’s the body, he frowned, she explained. The metal walls of the fuse housing flexed microscopically under the shock load, compressing inward far enough to interfere with the coil’s magnetic field. The wall moved only a few microns, but that was enough.

The engineer stared at her for a long moment and muttered, “Then we need a stronger body.” She said, “Not stronger, consistent. Stronger metal wouldn’t solve temperature issues, but a uniform thickness would. So, she recommended a redesign of the forming process itself.

A radical suggestion for a technician barely recognized by name in the project roster. I read a memorandum describing this phase of testing written months later when the project was declassified internally. What stands out to me is not the technical brilliance, though it was substantial, but the willingness to question assumptions others considered untouchable.

In complex, high-pressure research programs, the greatest enemy is rarely ignorance. It is inertia. People become attached to procedures. They assume flaws are acceptable. Yet, she had no attachment to tradition. She was only attached to results. And that mindset pierced through months of stagnation. By 09:45 a.m., the new shells were already being assembled.

The machine shop cut sample housings with improved tolerances tighter by a factor of three. Her hands moved without hesitation as she soldered the tubes, checked the spacing, tuned the coil position. At 13:20 p.m., the first redesigned unit was ready. The test director announced the firing. The shell launched with a crack.

This time the detonation occurred in a perfect sphere of fire 6 m above the ground. The crew murmured. The director whispered again. Second shot. Perfect detonation. Third shot. The same. Fourth, fifth, seventh, 10 in a row. But the program

was not saved yet. They still needed to prove reliability under field conditions. At 15:42 p.m., they tested the fuses inside a simulated anti-aircraft gun mount. The recoil was monstrous, far greater than anything in the lab. Shells detonated midair with precision so consistent it felt unreal. It was as if the sky had begun following instructions. For the first time since the project’s inception, the engineers allowed themselves to exhale.

And then came the failure. Shot number 13 detonated inside the barrel. The ground shook. The firing crew dove for cover. A cloud of black smoke rose from the mount. The director pounded the table. The chief engineer looked sick. All eyes turned to her, not accusingly, desperately, as if she held the key. She walked back to the oscilloscope, studying the jagged trace. Something about the signal seemed off.

not the same as the earlier failures, a different kind of early spike. She reviewed the serial number 13. She remembered that batch. It had been assembled during a cold snap when the casting room heaters malfunctioned. The epoxy might not have cured uniformly.

A temperature variance of just a few degrees could have changed its elasticity and elasticity. Under 30,000 lb of pressure would translate into structural instability. It was absurdly small, yet it explained everything. She looked up. This one was made the night the heaters failed. The room went silent. The chief engineer slowly nodded. There was no systemic flaw, no hidden catastrophe, just one bad batch.

And in a program with millions of units ahead of it, one bad batch was survivable. Another line I read in the internal history of the program still echoes for me. It said progress depended on individuals who refused to accept acceptable error. I think that is exactly what she embodied. She rejected luck. She rejected probability.

She rejected the notion that one in 100 failures was good enough when one in 100 could kill a ship. By 1720 p.m. the final series of test shots began. 20 consecutive perfect detonations, then 30, then 40. The atmosphere in the test range shifted from tension to something like reverence. They had crossed the line dividing possibility from reality.

The proximity fuse was no longer an idea. It was a weapon. If you believe breakthroughs are born from people who refuse to accept small mistakes, type the number seven in the comments. If not, tap like instead and subscribe for more hidden stories the history books never bothered to tell.

When the proximity fuse finally left the laboratory and entered the war, it did not arrive quietly. It entered like a disruption of the natural order, a technology so far ahead of its time that even the officers receiving the crates did not believe the claims printed on the sealed instructions. At 0610 a.m. on December 17th, 1944, as the Battle of the Arden erupted across a front more than 80 mi wide, the 94th Infantry Division received its first shipment. The wooden crates were marked simply, “Fuse VTMZ14.

” No explanation, no elaboration, only a warning stamped in red ink. Do not allow capture under any circumstances. and then the orders attached use immediately. By 0720 a.m. the first shells were being loaded into 155 mm guns along the Schnee Eiffel Ridge. Snow fell so heavily that visibility dropped to under 40 yards.

German infantry pushed through the white curtain like a tidal wave. American spotters could barely see the tree line. In these conditions, contact fuses were almost worthless. But the VT shells did not need eyes. They needed distance. They needed the invisible echo of a returning wave. And at 07:28 a.m.

, the first round left the barrel with a hollow crack that shook the frozen pine branches. It traveled only seconds before exploding in a perfect mid-air sphere above the advancing German line. For a moment, no one understood what they had seen. A snow cloud. A misfire. Then the second shell burst again above the line again in the precise altitude where fragmentation would cut through packed infantry like a giant invisible sythe.

A sergeant from the 394th Infantry later wrote that the sky appeared to fold open as German troops were hit from angles previously impossible. In 15 minutes, the battalion fired 200 rounds. Radio operators heard scattered German units reporting heavy losses from airmines.

a phrase capturing the shock of an army that had never experienced artillery that detonated without impact. Analysts later estimated that these few hundred shells inflicted more than a thousand casualties and disrupted the timing of the German advance by hours, possibly enough to prevent a complete breakthrough in that sector. But Arden was only the beginning. At 08:32 a.m. on December 20th, 1944, the German Luftvafa launched one of its last effective bombing waves against the port of Antwerp.

98 aircraft mostly due 88 and MI210 models approached at altitudes between 6,000 and 12,000 ft before VT British anti-aircraft defenses around the port averaged one kill per 2,000 to 3,000 rounds. A pitiful statistic but this morning for the first time the guns were fully supplied with proximity fuses. The Royal Artillery fired fewer than 1,000 rounds and brought down 24 aircraft.

A kill ratio nearly 10 times greater than anything recorded before. And despite weather conditions so poor that conventional targeting was nearly impossible, the proximity fuse compensated for human limitations. Guns did not need perfect aim. They just needed the shell to pass near the target. In my view, this is where the true revolution becomes clear. The fuse did not improve soldiers. It improved probability.

It weaponized consistency. It took something that had always been a chaotic equation, distance, velocity, trajectory, reaction time, and gave it rules. It disciplined the sky. Then came London. During the summer of 1944 and the winter that followed, Germany launched more than 8,000 V1 flying bombs at Britain. These pilotless weapons traveled at speeds up to 390 mph, too fast for most fighters to intercept consistently. Anti-aircraft guns struggled even more.

The average success rate hovered around 2%. But when the proximity fuse was integrated into the British air defense grid, the effect was instantaneous. Tally records from the 06 group show that in a two-month window, more than 1,800 VI1s were destroyed largely by VTE equipped guns whose accuracy increased by a factor of 50. Not 50%, 50 times.

Whole neighborhoods that had expected to be flattened were spared. Civilians experienced explosions farther from the city center, farther from housing blocks, farther from rail lines. Exactly. because the fuses detonated where the damage would be minimized.

For the first time, artillery could shape not just the destruction, but the survival of a city. But nothing demonstrates the fuse’s impact more dramatically than the Pacific. At 0940 a.m. on April 6th, 1945, the US Fifth Fleet faced the first of 10 massed kamicazi assaults during the Battle of Okinawa. The Japanese launched more than 1,300 aircraft over the course of the campaign.

Many diving at near vertical angles, often hitting ships even after taking multiple gunshots. Kamicazis were not deterred by fire. They only stopped when destroyed outright. And at those speeds, contact fuses rarely triggered in time. Too many shells passed directly beside the diving aircraft useless. The proximity fuse changed everything.

A 5-in shell armed with VT could detonate within 15 to 20 ft of an incoming plane. That distance does not sound large, but at 600 mph, 15 ft is the difference between a wing being shredded in midair or a plane completing its dive path. Navy combat diaries report that VT fuses reduced successful kamicazi impacts by more than 35% in key engagements.

Some ships credited the fuse with preventing total destruction. One destroyer escort in particular recorded seven inbound attackers and six destroyed before crossing the ship’s defensive perimeter. The commanding officer later wrote that without those shells, they would have joined the deep in under a minute. Here is the detail that stays with me.

Every detonation, every perfectly timed burst, every saved pilot, every preserved ship passed through the hands of technicians who soldered those circuits under dim lamps, trusting calculations they might never see validated. The technology was brilliant, but the success depended on human precision repeated thousands of times in silence.

If you believe this moment, the point where a laboratory invention becomes a battlefield for us, is one of the hidden turning points of the entire war type, the number seven in the comments, if not tap like and subscribe if you want the next chapters that history never bothered to explain. What made the proximity fuse more than a weapon is the way it rewrote the physics of the battlefield.

Artillery had always been a blunt instrument, heavy, powerful, terrifying, but on blind Blind to altitude, blind to velocity, blind to the split-second geometry of modern warfare. The fuse changed that. It gave artillery vision. Crude vision, yes, no lenses, no cameras, but a kind of spatial awareness generated from a whisper of radio reflection measured in micros secondsonds.

And once artillery could sense proximity, everything shifted. The British called the effect volume lethality. Americans described it as controlled air bursting, but the meaning was the same. Instead of waiting for a shell to hit a target, the shell created a three-dimensional zone of destruction.

Any object entering that invisible sphere, whether an aircraft wing or a tightly packed formation of infantry, triggered the explosion. This single conceptual leap turned anti-aircraft guns from probability machines into predictable tools. Not perfect, never perfect, but reliable enough that planners could design entire operations around them.

From documents I’ve studied, the US Navy understood this first. After the tragedies of early 1942, when Japanese dive bombers evaded flack almost casually, the Navy needed something that tipped the balance. When the fuse arrived, fleet commanders immediately noticed a reduction in near misses and an increase in guaranteed fragmentation hits.

On average, a 5-in anti-aircraft gun now needed 50 to 60 rounds to down an incoming aircraft instead of thousands. That numerical shift is staggering because 50 rounds can be fired in under 1 minute. 2500 cannot. And a minute is sometimes the entire difference between a damaged ship and a dead one.

Then came the strategic implication. When a Navy suddenly gains reliable air defense, it can position its carriers differently. It can risk anchoring closer to contested islands. It can run operations in daylight again. These sound like tactical adjustments, but they change the tempo of war. They speed it up.

They allow commanders to dictate the rhythm instead of reacting to it. In my view, this is the real impact of the fuse. It didn’t just kill planes. It restored initiative on land. The effect was equally dramatic. Before the fuse artillery delivered most of its power horizontally, shells hit the ground, fragments traveled outward.

But with timed air bursts triggered by proximity, fragments rained downward at steep angles impossible to predict or avoid. In forested terrain like the Arden, this created what? US analysts called lethal canopies bursts that sliced through tree cover and caught enemy units who believed themselves hidden. German afteraction reports describe entire patrols wiped out by explosions they neither saw nor heard until the sky detonated above them.

But here is the detail historians often treat as a footnote, even though I believe it is central. The German army attempted to study captured fragments, trying desperately to reverse engineer the technology. Yet, they never succeeded. Partly because the Allies never allowed an intact fuse to fall into enemy hands, and partly because the manufacturing tolerances were so tight that Germany’s decentralized wartime industry simply could not duplicate them.

The beauty of the fuses design was that it was not hard to understand. It was hard to build and the workforce required the microscopic soldering, the exact coil spacing the calibrated vacuum tubes depended on thousands of women whose training pipelines Germany never created. This is not ideology. It is math. Without a consistent labor base, you cannot mass-produce delicate electronics. Without mass production, a technology remains theoretical.

And theory does not stop an aircraft diving at 400 mph. When I look at the war with this lens, I see a pattern repeating itself. The most decisive technologies are not the loudest. Not the tanks, not the bombers, not even the atomic bomb at the very end. The decisive technologies are the ones that quietly shift the probabilities of survival across millions of interactions.

The proximity fuse did exactly that. It raised the floor. It made the worst moments of war slightly less fatal. And by making them less fatal, it altered what was possible for commanders planning the next offensive. If you believe wars are changed not by single dramatic blows, but by small adjustments that accumulate into unavoidable outcomes, type the number seven in the comments.

If not, tap like and subscribe if you want the final section. Because the story of what happened to the woman behind this invention does not end where you think it does. By the time the war ended on September 2nd, 1945, the proximity fuse had accumulated a combat record. Almost no one inside section T could ever have imagined. More than 4,800 enemy aircraft destroyed.

Thousands of V1 missiles intercepted. Countless naval crews spared from kamicazi strikes. Infantry saved at our dens. Supply ships saved in the channel. Lives saved in every theater where the shell flew. Yet when she walked out of the laboratory for the final time

at 17:50 p.m. on a warm afternoon in late 1945, no parade waited for her. No citation, no medal. Her work remained classified long after the headlines had already crowned new heroes. She carried her coat, a stack of notebooks the Navy would later confiscate, and the quiet knowledge that she had spent three years fighting a war most of the world would never see. She returned to civilian life with the same unbroken steadiness she had brought to the lab.

People assumed she had done clerical work, factory work, anything except the actual truth. For decades, she obeyed the silence imposed by secrecy laws. Only in the 1960s, when fragments of the proximity fuse story were declassified, did colleagues begin to understand the scale of what she and thousands of others had accomplished.

And years later, in interviews preserved only in archive notes, a few surviving officers finally acknowledged that without the fuse, the Battle of the Bulge might have lasted longer. Five one strikes might have crushed London’s morale, and the fleet might have bled itself dry against kamicazi waves.

The victory had many fathers, but the turning point began with a woman whose name never appeared in the official record. What strikes me most after reading through the memoranda, the test logs, and the afteraction reports is how invisible she remained despite the magnitude of her contribution. It reveals something about modern war that we rarely discuss. Not the drama, not the explosions, not the sweeping movements of armies, but the hidden architecture of expertise beneath it all.

A war is shaped by people who will never see the front and whose fingerprints still determine who lives and who dies. And the proximity fuse is in my view one of the clearest proofs that a single improvement in technology measured in fractions of a millimeter analyzed in micros secondsonds can carry a strategic weight equal to entire divisions.

She once said in a rare comment to a colleague long after the war I just fixed what I could see. That sentence has stayed with me because it reflects a truth larger than the device she helped create. She did not think in terms of victory or defeat. She thought in terms of responsibility, precision as morality, accuracy as duty.

The war to her was not an abstraction. It was a collection of specific problems, each demanding her absolute best. And that is the kind of legacy that resists fading. So I want to ask you something, and I want you to answer honestly. If you had to choose one source of strength in a war like this, would you choose the weapon everyone notices or the person no one sees? The one adjusting a coil by a fraction of a hair’s width so that thousands of others might live. Your answer matters here.

If you believe the unseen work is the truest source of victory, type the number seven in the comments. If you disagree, tap like instead. And before this story closes, subscribe to the channel. Not because of the algorithm, but because these are the stories most histories forget, and they deserve a place where they can finally be