Japan. Late 1944. The war was turning against the empire. American carriers ruled seas where Japanese ships once felt invincible. B29 bombers had started appearing high above the clouds. Fuel was short. Steel was precious. Time felt thin. Inside a windowless concrete room at Kuret Naval Arsenal, a group of Japanese naval officers stood around a long table covered with a canvas sheet.

They were not young heroes from posters. They were older now, tired eyes, loose uniforms, faces marked by worry. At the head of the table stood Commander Ishiawa. He was a weapons specialist. He had spent his life believing in Japanese naval superiority. He believed in the long lance torpedo. He believed in night fighting tactics.

He believed in the spirit of the Imperial Navy. Now he believed in something else. He believed they were running out of advantages. The door opened. Two sailors carried in a wooden crate. It was scorched, water stained. On the side, burned into the wood, were English letters. The crate had been recovered from floating wreckage after a sea battle.

It had been lashed inside a damaged American gun turret. The sailors set it on the table with a dull thud. Some officers smirked. We risk ships and they send us a box. Tired laughter rolled around the room. Commander Ishiawa did not laugh. He had read the pilot reports. He had seen the new pattern of explosions around Japanese aircraft.

Something about American anti-aircraft fire had changed. It felt too accurate, too deadly. His hand rested on the crate. This, he said quietly, came from a gun that seemed far too precise. Our pilots say the shells now explored near them, not on them, not from a simple timer or impact. He nodded once. Open it.

The sailors pried the lid off with a crowbar. Nails squealled. Wood splintered. The top finally came free. Inside, wrapped in stained cloth and sawdust, was a single metal device. It did not look impressive. It was about the size of a cooking pot, cylindricical, heavy, flat mounting brackets on one side, no glass dial, no obvious timer wheel, no clockwork, just a stubby connector and stamped numbers.

Lieutenant Sato, the youngest officer, shook his head. “This is what your pilots fear?” he asked. “A little drum of American scrap metal.” Several men chuckled. To them, Japanese weapons were elegant and refined. “This looked plain and ugly.” “American industry,” one officer said. “Bute force, no finesse.” Commander Ishikall watched silently.

He turned toward the man in the corner, a short civilian with wireframe glasses and a stained lab coat. Dr. Tanab, electronic specialist. Doctor, Ishikawa said, “We need your judgment.” Tanab stepped forward. He was not impressed by uniforms. He was impressed by circuits. He ran his fingers along the casing, feeling seams and screws.

Careful, an officer warned. It might still be armed. He snorted softly. If it survived the turret explosion, seawater, and your recovery team, either it is very well designed or already very dead. He pointed to a faint ring of bolts. Open it here. Technicians clamped the device in a vice and began loosening the fasteners.

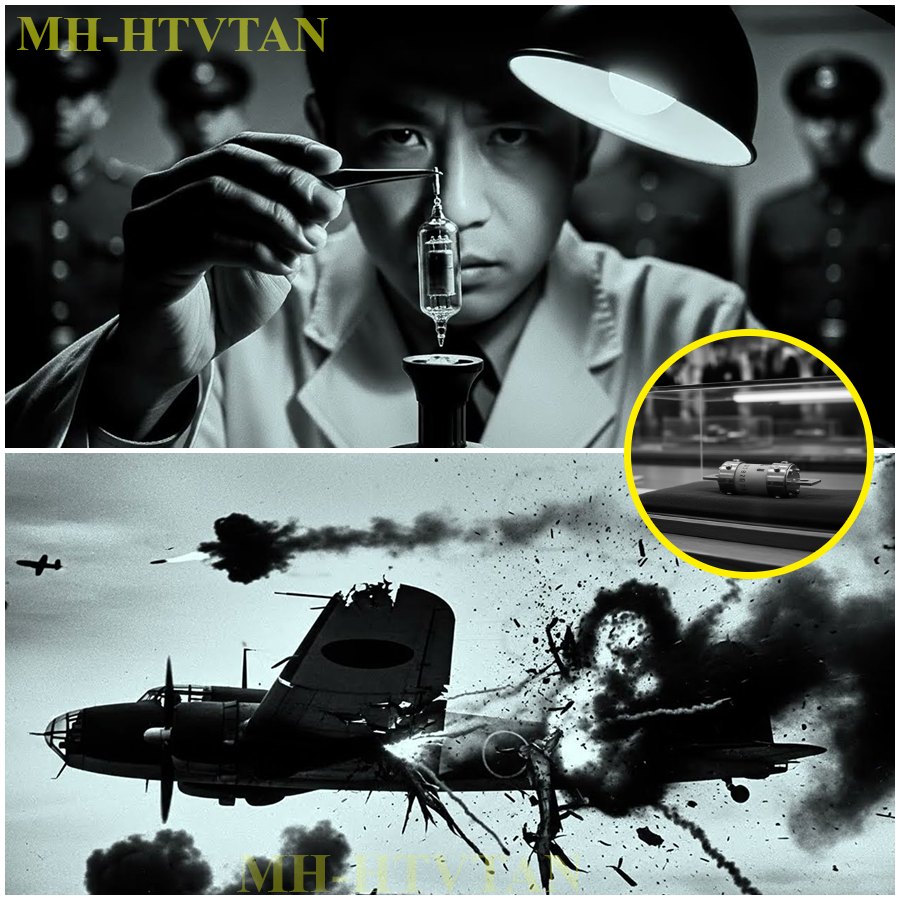

As they worked, Tanab noticed the bolts. They were perfectly made, standardized, machine accurate, not handmade, not experimental. This was made by the thousands, not as a testpiece, as a routine product. The last bolt came free. Carefully, they lifted off the outer shell. Inside, the officers expected heavy springs and gears. Instead, they saw something else.

coils of copper, condensers, tiny resistors, fine wires looping in careful patterns, and in the center, like a tiny glass jewel, a compact vacuum tube, electric, not clockwork, a fuse that was also a radio. The laughter stopped. The device now lay open like a dissected heart. No gears, no ticking springs, only coils, tiny parts, and that compact vacuum tube in the center. One older officer frowned.

This cannot survive firing from a gun, he said. The acceleration would crush it. Tonab shook his head slowly. That,” he replied, “is exactly what troubles me, because they clearly trusted it enough to put it inside real shells.” He gently lifted the vacuum tube with tweezers. It was small and rugged, more compact than the large, fragile tubes Japan used in radios.

“This is not a laboratory toy,” Tanabbe said. “This is production. This is industry. He set the tube back into place and traced the wiring to one of the coils. “This rope here,” he said. “Looks like an antenna.” Lieutenant Sato squinted. “A fuse with an antenna?” he asked. “That makes no sense. A shell travels too fast.” Tanabi’s eyes brightened.

“Exactly,” he said. And yet your pilots report shells exploding when they only pass near them, not just when they hit. He asked for a small test bench. Soon, a battered field radio, a power supply, and some wires were brought in. The technicians wired the device to a meter and a lamp instead of a detonator. “We will see if its sensing circuit is still alive,” Tanab explained.

He flipped the improvised power switch. For a moment, nothing. Then the meter needle twitched. A faint hum came from the coil. “It lives,” he whispered. “Bring me something metal,” he ordered. “A toolbox, a helmet, anything.” They brought a steel toolbox. “Move it slowly toward the device,” Tanabe told Sato.

Sato moved the box closer. The needle began to climb. “Stop,” Tanab said. The box hovered in the air. “Now pull it back.” Sat did. The needle dropped again. Closer. The needle rose. Farther it fell. Officers leaned in, faces tense. “This is not the timer,” Tanab said quietly. It is eliciter. As the shell flies, this device sends out a small radio signal.

When that signal reflects off something nearby, the echo changes the circuit. When the echo is strong enough, the fuse decides it is close enough and triggers the explosion. He looked around the room. In other words, gentlemen, the shell does not wait for a guess. It explodes when it feels that you are near. No one laughed.

Now, the lab test had proven the principle, but war is not fought on tables. Commander Ishiawa wanted proof in the real world. We must see what it does in flight, he said, even if we cannot copy it. Weeks later, at a coastal test range, a small group of officers stood on a concrete platform facing the sea. The air smelled of salt and old gunpowder.

Below, a test launcher was set up to fire inert shells over the water. On a nearby table set a copy of the American device. Dr. Tanab had built it with his team. Same size and shape, same kind of circuit, but no explosives. In place of a detonator, he explained, we have attached a flare and an indicator.

If the fuse decides it is close enough to a target, it will fire the flare. The target was a salvaged section of aircraft wing mounted upright on a metal frame. Ugly, bent, but made of real aircraft aluminum. The plan was simple. Fire the test shell past the wing. See if the fuse reacts when it comes near. The shell was loaded. The officers stepped back.

Fire, Ishikawa ordered. The launcher boomed. The shell shot into the gray sky. A dark blur. For a heartbeat, nothing. Then a flash of brilliant light blossomed just off the edge of the wing. Not on it, not far away, right where near became too near. Officers flinched. Someone swore. The range crew checked their instruments.

The shell did not hit the wing, a man shouted, but the flare went off at a distance where fragments would be lethal. Again, Ishikawa said, they fired a second shell. Same result. Another flare appeared close to the metal wing, timed by nothing human. Tanabe folded his arms. “Your pilots were telling the truth,” he said.

“The Americans of no longer aiming only at aircraft. They are filling volumes of sky with shells that explode when they come near something solid.” He looked out over the water. Any plane that flies through that space, he added quietly, flies into a trap it cannot see. The officers understood now. This was not just better aim.

This was a new way of thinking about flack itself. The sky was no longer random danger. It was being programmed by a small, ugly American device that Japan had once laughed at. Far from the test range, a Japanese fighter pilot named Lieutenant Nakajima learned about the device the hard way. At first, he thought the stories were exaggerations, squadron rumors, magic American shells, explosions that knew where you were.

He had flown under flack before. You could weave between bursts, trust your instincts, hope your luck held. But on an escort mission for dive bombers attacking an American task force, he saw something different. As they approached the fleet, the sky erupted, not random, not scattered.

The bursts came in lines, steps of fire. Nakajima watched a pattern of explosions appear in front of his path, as if the guns had guessed where he was going. He yanked his fighter off course. The next cluster of bursts appeared where he turned. His cockpit shook from the blast waves. Shrapnau rattled against his wings. Ahead of him, a bomber flew into one of those invisible zones.

The shell did not hit it directly. The explosion went off nearby. The bomber’s wings suddenly shredded as if carved by invisible blades. The aircraft rolled, burned, and fell. Back on the ground, pilot spoke in low, tense voices. The flock is different. It explodes when you are close, not when the clock says so.

It feels like the sky is learning us. Later, an intelligence briefing confirmed it. An officer laid a sketch of the American fuse on the table. This, he said, is inside many of their shells now. It does not wait for a timer. It listens for your aircraft and explodes when the distance is right. A pilot whispered. So the shell is thinking.

No, the officer replied. Not thinking, just obeying its design faster than any human can. For Nakajima, the message was clear. His skill still mattered. His courage still mattered. But somewhere inside each American shell, a small device was now making its own deadly decision based only on distance. Back at a mored naval ship near Kuray, Commander Ishiawa sat in a wardroom with Captain Kobayashi and an army liaison officer.

On the table between them lay a folder filled with reports, pilot testimonies, gun crew notes, burst pattern diagrams that now looked chillingly similar to the test range results. Kobayashi rubbed his eyes. For years, he said, we trained our gunners to create patterns, dense walls of fire. We knew it was imprecise, but we trusted volume.

He tapped the papers. Now the Americans do something else. They do not fire at points. They fire at areas. Shells explode when they are near you, not when a clock guesses. The army officer looked at Ishiawa. “Your specialists say we cannot copy this,” he asked. Ishiawa answered honestly.

“We can understand it,” he said. “Dr. Tanab has mapped the principle. It is a tiny radio. It listens for its own echo.” He spread his hands. But to produce thousands, rugged enough for firing, sealed against shock and moisture, requires an industrial base we no longer have. We lack copper. We lack factories. We lack time. Kobayashi gave a bitter half smile.

In other words, he said, to match it, we would need to be the United States. Silence settled. Finally, the army officer asked, “Then what do we tell our pilots and captains that they are helpless?” “No,” Ishiawa said firmly. “We tell them the truth. The enemy has improved his guns. Flying straight and steady into that fire is suicide.

” Now, he leaned forward. “We cannot outbuild this device,” he said. But we can change tactics. Lower altitude, different angles, night attacks, anything that forces the Americans to guess instead of feeding perfect approaches to their fuses. Kobayashi exhaled. So we ask our men to fight like ghosts, he said quietly.

Not like the heroes we promised them they would be. It was a painful admission. The old ideal of pure spirit versus pure metal had cracked because a small American device was quietly making courage alone no longer enough. The war ended not with one last great battle for Commander Shikawa, but with a radio broadcast.

The Emperor’s voice, words of surrender. Endure the unendurable. Japan lay in ruins. In some forgotten cabinet at Kuray, an American device sat on a shelf, tagged and stored among many other defeated ideas. Months later, under Allied occupation, a group of Japanese engineers and officers were summoned to a technical meeting in Tokyo.

The room was now under Allied control. American guards at the doors, bright electric lights, English charts on the walls. Major Collins, an American officer, stood at the front. Through an interpreter, he spoke calmly. “We have been instructed to show you certain wartime technologies,” he said. “The hope is that understanding them will prevent future misunderstandings.

” He pulled a cloth from the nearest object on the table. There it was, a complete proximity fuse intact. Next to it, a neat cross-section showing every part inside. Coils, condensers, vacuum tube, all arranged with precise care. Japanese engineers leaned in. Dr. Tonab stepped forward, eyes fixed on the device.

What you recovered during the war was likely damaged, Collins explained. This is the fuse as we produced it. He pointed to a wall chart. Peak output, he said, reached about 1 and a half million units per month. The interpreter repeated the number. The Japanese officers went silent. They had struggled to protect a few crucial tubes.

The Americans had turned them into ammunition by the million. Collins continued, “Some of our own officers laughed at the idea at first,” he said. “A fuse that could listen in flight sounded ridiculous.” He gave a small smile. “They stopped laughing when they saw it work.” Tanabe nodded slowly. in our labs,” he said quietly.

Some of our officers laughed too. They saw only a dull metal can and called it crude, American, ugly. He looked at Collins. Then we opened it, he said. “No anger, only respect and the taste of a hard lesson learned. Too late.” Two decades later, Japan was rebuilding as a modern nation. Factories ran at full speed. Students filled universities. The war was now history.

In a university lecture hall in Tokyo, Professor Tonab stood at the chalkboard. On the desk beside him sat a glass case with a small metal cylinder inside, a cutaway proximity fuse mounted on velvet. During the war, he told his students, Japan believed courage and a few superior weapons would be enough. He drew a torpedo and a fighter on the board.

“We had some excellent machines,” he said. “But our enemy had something different, a system that could build millions of clever devices faster than we could understand even one.” He pointed to the fuse in the case. This, he said, is one of those devices. He explained it in simple terms. A tiny radio inside a shell. It sends out a signal.

When that signal reflects off an airplane and grows strong, the fuse decides to explode. A student raised his hand. Sensei, did we know about this during the war? He asked. Yes, Tonab replied. We captured pieces. one nearly intact unit. Some officers laughed. A few of us understood what it meant. He sighed. But we could not become a country that could build it in time.

We lacked the factories, the resources, the stability. He wrote one more word on the board. Underestimation. Remember this, he told them. When you see a small ordinarylooking device, do not assume it is simple. Our officers once laughed at this fuse. He looked down at it. Now he finished. I make my students look at it so they never make that mistake again.

Across the ocean in America, an old engineer named Arthur Levy sat at his kitchen table holding a proximity fuse in his hands. He had worked on them during the war, not as a soldier, but in a guarded lab full of test equipment. He had never seen a Japanese pilot, never heard flack from below. He had only seen waveforms on screens and coils on workbenches.

His grandson stared at the device. “It’s so small,” the boy said. Arthur smiled. A lot of important things are,” he replied. He explained in simple words, “We built these to help our guns hit faster planes. Before this, our shells wasted most shots. With this, they exploded near the enemy instead of hoping for a perfect hit.

” He rubbed his thumb along the metal. Back then, we thought mostly about our own boys on ships, he said. We didn’t see the faces on the other side of the ocean. Years after the war, at a joint technical conference, Arthur had met a Japanese engineer. The man had bowed slightly and said, “We studied your fuses.

Our pilot thought your shells were just lucky. Then we saw these and we knew it was not luck,” he had added quietly. “Some of our officers laughed when they first saw one. We did not laugh after we opened it.” Now at his kitchen table, Arthur closed the case around the fuse. “Wars are not always decided by big things,” he told his grandson.

Sometimes they are decided by something small humming where no one can see it doing its job a million times over. He looked at the boy and by whether people who see it first, he said, laugh at it or try to understand it. Years later, in a quiet war museum in Japan, a woman named Kaio stood in front of a small glass case.

Her father had flown missions in the last year of the war. He rarely spoke about them. When he did, he mentioned American shells that seemed to know where we were. Inside the glass, Kyo saw metal fragments and a cutaway proximity fuse. The plaque read in Japanese and English, US proximity fuse, radio-based detonation when near aircraft, mass- prodduced in the millions, increased Allied anti-aircraft effectiveness.

Next to the case was an old black and white photo. Japanese officers and engineers stood around a table bent over an opened fuse. Their faces were serious. No one was laughing. A quote on the wall caught her eye. It was from a former Japanese officer. When we first saw the American device, some of us laughed.

It looked like a dull little box. We believed no box could defeat Japanese spirit. Then we opened it and understood their factories were fighting us, too. Another quote from an American historian read, “The proximity fuse was not as famous as the atomic bomb or the rocket, but it quietly changed the geometry of the sky.

It showed that after a point, courage alone could not defeat smart weapons backed by industry.” Kyo thought of her father’s words. He had said once, “We were not beaten only by bombs and ships. We were beaten by how many clever things they could hide inside every weapon, and by how late we understood that. She looked at the small fuse one last time. It made no sound. It did not move.

But once thousands like it had filled the air over oceans and islands, listening for wings. When people say Japan laughed at the American device until they opened it, they are not just talking about one fuse in one room. They are talking about a bigger lesson. Never underestimate what you do not yet understand.

Never assume courage can ignore technology. And never forget that sometimes the most dangerous thing in a war is the small object everyone laughed at until it quietly changed the rules.