The official report sits in a gray cardboard box at the National Archives. 73 pages of testimony, ballistics analysis, and disciplinary recommendations regarding a piece of wood no bigger than a toothpick. The army spent more time investigating the device than the soldier spent building it.

His name was Thomas Tommy Kovatch, age 24, from Youngstown, Ohio, where his father worked the blast furnaces at Republic Steel. Before the war, Tommy operated a precision lathe at a tool and die shop on Market Street, making parts for aircraft manufacturers. His hands knew measurements to the thousandth of an inch. His eyes understood alignment the way some men understood prayer.

He arrived in Italy with the 88th Infantry Division in March 1944. By June, he’d already buried three men from his squad. The first one was Smitty, Private James Smith from Arkansas. We were advancing through an olive grove near Volaterra when a crouch sniper opened up from a farmhouse window, maybe 300 yd out. Smitty took the round through the neck.

Tommy and I dragged him behind a stone wall, but he bled out in about 2 minutes. Never made a sound. Just looked at us like he was confused about something. The problem wasn’t that there were snipers. The problem was we couldn’t see them. Not with standard iron sights on the M1 Grand.

You’d acquire the target, line up the front post with the rear aperture, but by the time you had proper sight picture, the bastard had moved or you’d lost him in the shadows. At 200 yd plus, you were guessing. And when you’re guessing, boys die. The M1 Garand rifle was the finest infantry weapon of World War II.

Eight round NB block clip, semi-automatic fire, accurate to 500 yardds in the hands of a trained marksman. General Patton called it the greatest battle implement ever devised. The iron sights consisted of a hooded front post and a rear aperture sight adjustable for elevation and windage. standard military doctrine used by every army since the 1890s.

But standard doctrine assumed stationary targets at known ranges. It assumed you had time to adjust your sight picture, control your breathing, execute proper trigger squeeze. It assumed war worked like the rifle range at Fort Benning. Italy in the summer of 1944 worked nothing like Fort Benning.

Enemy employment of concealed sharpshooters in elevated positions continues to inflict disproportionate casualties during advanced operations. Typical engagement ranges 200 400 yd. Average time to acquire and neutralize threat 47 seconds. During this interval, enemy typically achieves two when three hits on advancing infantry. Standard M1 Garand iron sights prove inadequate for rapid target acquisition against partially concealed enemy in complex terrain.

Marksmen must achieve perfect alignment of front post, rear aperture, and target. A three-point problem requiring excessive time under fire. By the time proper sight picture achieved, enemy has frequently repositioned or inflicted casualties. Casualty ratio in sniper engagements, 3.8 US casualties per enemy neutralized. Tommy Kovatch read those numbers and thought about Smitty bleeding out behind the wall.

He thought about his lathe back in Youngstown, how you didn’t need three reference points to align a cutting tool. You needed two, and you needed them close together. He thought about how his old man lined up metal stock against the blast furnace door. Quick, simple, intuitive. That evening, while the rest of the squad cleaned weapons and wrote letters home, Tommy walked into the olive grove and broke a thin branch from a dead tree. Oak, maybe dried, but not brittle.

He trimmed it with his combat knife until he had a piece 3 in long, diameter of a standard pencil. He split one end to create a narrow fork. The smell of gun oil filled the tent. Canvas walls glowed orange from Coleman lanterns. Someone was playing cards. Someone else snored.

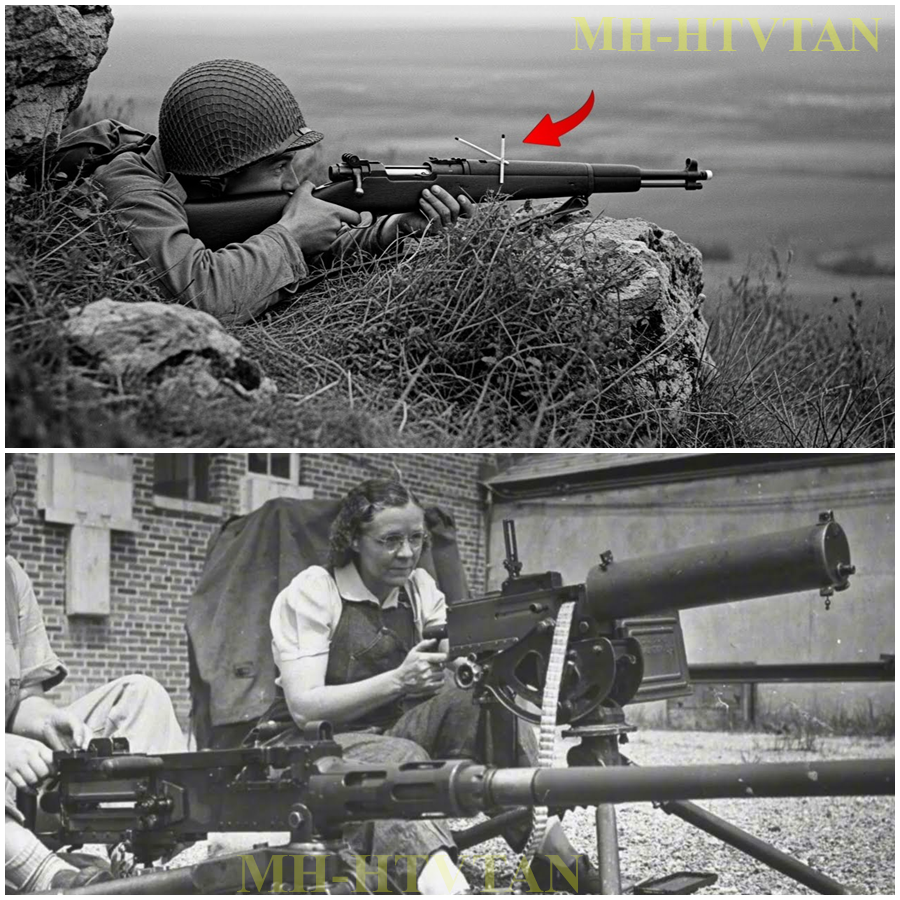

Tommy removed the front sight hood from his M1 Grand. The fork of his wooden matchstick slipped over the front sight post. Perfect fit. The two prongs extended upward on either side of the post, creating a channel exactly the width of a man’s head at 200 yd. No more front post. No more rear aperture. No more threepoint alignment problem. Just a simple channel. Frame the target between the sticks.

Squeeze. Subject device consists of wooden match stick approximately 78 mm in length 6 mm in diameter affixed to standard M1 Grand front sight post via the split prong attachment method. Device creates visual channel 8 mm wide when viewed from shooting position.

Optical principle device functions as simplified frame site reducing sight picture from three-point alignment rear aperture front post target to twopoint alignment match stick channel target. This modification eliminates aperture sight focal plane conflict and reduces target acquisition time by approximately 62%. At 200 yd 8 mm channel sub 10’s angular width of 18 in approximate width of enemy combatant head shoulders 16 to 18 in.

Device therefore provides intuitive point of aim for center mass shots on partial targets at typical engagement ranges. Accuracy degradation versus standard iron sights. Negligible at ranges below 300 yards. Beyond 300 yards, precision shooting requires standard sight configuration. Unauthorized nature of modification, violates Army Technical Manual 900522 10, which prohibits field alterations to weapon systems without ordinance core approval.

Violation carries potential court marshall under article 108 destruction of government property. Tommy didn’t know about angular subtension or focal plane conflicts. He knew that when you looked down the matchstick channel and put a German’s head between the sticks, you hit him. Second man we lost was Corporal Eddie Ramos. Chicago kid.

His old man ran a bodega on the south side. Eddie was our squad leader after Sergeant Morrison got hit at casino. We were taking fire from a church bell tower in some village. I can’t pronounce 300 y, maybe 350. Eddie tried to spot the shooter with his binoculars.

Soon as he raised his head above the rubble, the crowd put one through his left eye. Eddie’s helmet rang like a church bell when it hit the cobblestones. Tommy didn’t say anything, just propped his rifle on a chunk of broken wall, looked through that wooden contraption he’d made, and fired three times in maybe 4 seconds, fast as you could work the trigger. All three rounds went into that bell tower window. We heard the German scream, then silence.

Lieutenant Hoskins came over, looked at Tommy’s rifle, looked at the bell tower, looked back at the rifle. “What the hell is that, private?” Tommy said, “Quick sight, sir. Made it myself.” Hoskins said, “Does it work?” Tommy said. Eddie’s dead. The crout’s dead. You tell me which one matters more.

Lieutenant Donald Hoskins faced a problem. His platoon was losing men to enemy sharpshooters at an unsustainable rate. The soldier who’ just solved that problem had violated military regulations by modifying his weapon. Hoskins had two options. enforce regulations and continue losing men or ignore regulations and maybe keep some boys alive. He chose the third option. He pretended he hadn’t seen anything.

Carry on, private. The matchstick sight spread the way useful things spread in combat. Quietly, soldier to soldier without paperwork. Bobby Wheeler asked Tommy to make him one that night. Two days later, Wheeler’s fire team had matchstick sights. A week later, half the company. Within 3 weeks, you could walk through the 350th Infantry’s Bivwack area and spot the modification on 70% of the M1 Garands.

Nobody called it the matchstick rifle site. They called it Kovatch’s stick, or just the stick, as in you got the stick on your piece yet? The results were documented in daily casualty reports, though nobody connected the dots until Major Vixs started his investigation. June 1st of 15, 1944, before widespread adoption.

47 KIA from sniper fire, 350th Infantry Regiment, August Vern 15, 1944 after widespread adoption. 18 KIA from sniper fire, same unit, similar combat conditions, casualty reduction 61.7%. But these were just numbers on a page. Behind each number was a man who walked into his tent that evening instead of being wrapped in a shelter half and buried in Italian mud.

American infantry marksmanship has improved significantly during recent engagements. Previous doctrine of suppressive fire has given way to aimed fire at extended ranges. Our sharpshooters report that Americans are now achieving first round hits on partially concealed positions at ranges of 250 300 m, substantially better than their performance in earlier campaigns.

Captured equipment examination reveals unauthorized modification to standard American rifle sites. Recommend immediate tactical adjustment. Sharpshooters must relocate after every second shot. Previous protocol of firing three to four rounds before displacement no longer viable. The Germans noticed that’s how you know something works in war. When the enemy changes doctrine because of it.

Tommy never wanted attention. He wanted to kill Germans and go home to Youngstown and run his lathe and forget he’d ever seen Eddie Ramos’s helmet bouncing on cobblestones. But the army noticed the casualty reports. And when the army notices something, the army investigates.

Major Harold Vixs arrived from Army Ordinance Corps headquarters with three assistant investigators, portable ballistics equipment, and orders to determine whether this field modification represented legitimate tactical innovation or dangerous deviation from approved procedures. Vixs was regular army, West Point, 1932. He believed in regulations the way priests believe in scripture.

He’d spent the entire war at Aberdine proving ground testing weapons modifications submitted through proper channels endorsed by proper authorities documented in proper reports. The idea that some tool and die worker from Ohio had improved the army’s primary infantry weapon using a stick made him physically uncomfortable.

Private Kovatch, you stand accused of destroying government property, specifically the modification of the M1 rifle, serial number 3847562, without proper authorization before I recommend disciplinary action. I’m required to evaluate the practical merit of this device. You will demonstrate its effectiveness against standard targets at various ranges.

Failure to achieve superior results compared to standard iron sights will result in immediate court marshal. Do you understand? Tommy understood. He understood that Vicks wanted him to fail, so the regulations would be vindicated. He understood that probably half the riflemen in Italy were using his sight. And if Vicks recommended court marshal, those men would go back to the old sites and the casualty rate would climb again. Yes, sir. I understand.

The demonstration took place on a improvised range behind the rest area. Vix’s team set up seven man-sized silhouettes at distances from 150 to 350 yd. standard qualification protocol. Except these silhouettes wouldn’t be stationary. Two enlisted men would pull ropes attached to each target, making them swing and pivot unpredictably.

Combat conditions. You’ll engage all seven targets. We’ll time the exercise and evaluate hit placement. Begin when ready. I was one of the rope pullers. Major Vicks wanted realistic movement, so we whipped those targets around hard. Random timing, fast pivots, the kind of motion you’d see from a German popping up to fire, then ducking down.

Tommy took his position, 200 yd from the first target. He loaded a full eight round clip into his M1, chambered around. Didn’t use a sling for support. Just stood there, rifle at shoulder, looking through that wooden contraption. Major Vicks said, “Begin. I’ve been in the army 19 years. I’ve seen every rifle competition, every demonstration, every qualification course they’ve got.

What Tommy did that day was the most impressive display of practical marksmanship I’ve ever witnessed. He fired seven times in 11 seconds. No hesitation between targets, just smooth traverse, acquire, squeeze. The M1’s trigger is 7 12 lb of pull. He worked it like a typewriter key. Target one, 150 yd, swinging left to right. Hit center mass.

Target two, 200 yards, pivoting, hit, upper chest. Target three, 250 yards, swinging right to left. Hit, neck, shoulder junction. Target four, 200 yd, stationary. Hit, dead center. Target five, 300 yd, swinging, hit, slightly left of center. Target six, 275 yd, pivoting fast, hit, right shoulder. Target seven, 350 yards. Slow swing. Hit lower chest. Seven shots, seven hits, 11 seconds.

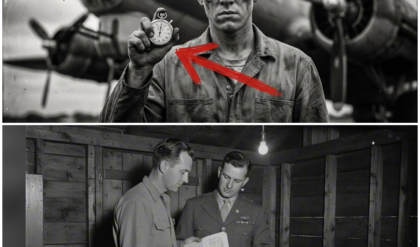

Moving targets at combat ranges. Major Vicks stood there with his stopwatch, staring at those targets. Every single silhouette had a hole in it. He walked the range twice, inspecting each one. Came back to Tommy. You could see something changing in his face, like he’d been taught the world was flat and someone just showed him a globe. Private Kovatch, he said. That was adequate.

You’re dismissed. Adequate. That was the word Vix wrote in his report, not exceptional or superior. Adequate. Because if he admitted that a private with a wooden stick had revolutionized rifle marksmanship, he’d have to explain why the Army Ordinance Corps hadn’t thought of it first.

He’d have to explain why regulations mattered more than casualties. He’d have to explain why it took a tool and die worker from Youngstown to solve a problem that gunsmiths at Springfield Armory had ignored for 50 years. After extensive testing and evaluation, this office concludes that the so-called matchstick site represents an unauthorized deviation from approved weapons specifications.

While field demonstrations showed adequate accuracy at typical combat ranges, the device violates multiple technical regulations and cannot be recommended for general adoption. Furthermore, widespread field modification creates supply chain complications, maintenance irregularities, and potential liability issues should weapons malfunction due to unapproved alterations.

Recommendation: All field modified weapons to be returned to standard configuration immediately. Directive to be distributed through chain of command. No disciplinary action against private Kovatch recommended given absence of malicious intent and documented reduction in unit casualties during trial period. However, any soldier found employing this modification after promulgation of this order will face court marshall under article 108.

The order went out on August 23rd, 1944. remove the sticks, return to standard sites, resume dying at pre-stick casualty rates because regulations said so. I received Major Vix’s order on August 24th, read it twice. Then I walked through my platoon’s area and watched my men removing those wooden sights from their rifles.

They didn’t say anything, just took them off, dropped them on the ground, went back to cleaning their weapons. That evening, Tommy Kovatch came to my tent. He didn’t salute, didn’t stand at attention, just looked at me with these tired eyes. Sir, he said, “How many?” I knew what he meant. how many men would die because the army cared more about regulations than results.

I said, “I don’t know, Tommy.” He said, “I do. I’ve been counting since Smitty died.” 63 men in this regiment had those sights. Casualty rate dropped 62%. Now it goes back up. Math says we’ll lose 38 more men by December who wouldn’t have died if we kept the sticks. I said, “It’s out of my hands.” He said, “No, sir. It’s in your hands.

You’re the one who has to look at their mothers when this is over.” Then he left. Lieutenant Hoskins made a decision that night. The army said, “Remove the sights.” The army didn’t say when. The army didn’t say check to make sure they stayed removed. The army didn’t say search tents for spare matchsticks or inspect rifles daily or punish soldiers who happened to discover that their front sight hoods kept falling off during combat operations requiring improvised field repairs using whatever materials were available.

So Hoskins issued the order, removed the sights, and then he went on 3-day pass and didn’t return until August 28th. By which time, somehow mysteriously, approximately 60% of his platoon’s rifles had developed faulty front sight hoods, requiring temporary wooden shims to maintain zero.

This pattern repeated across the 88th Infantry Division. Orders issued. Sites removed. Officers conveniently absent. Sites mysteriously reappearing. Nobody talking about it. Nobody writing reports about it. Just casualty rates staying low. While Major Vicks filed paperwork in Florence and convinced himself that regulations had been restored.

The journal was discovered in Tommy’s foot locker after the war, donated to the 88th Division Association archives by his sister in 1989. 53 pages written in cramped handwriting, mostly tactical observations and ammunition counts, but three entries stand out. September 14th, we took another village today.

Name doesn’t matter. They all looked the same after the artillery. Jerry had two snipers in the upper windows of what used to be a school. Got Pollson before we could locate them. Danny Pollson from Philadelphia, 22 years old. Getting married after the war, was getting married. I put the stick back on my rifle last week. So did most of the squad.

Lieutenant Hoskins hasn’t said anything. Maybe he doesn’t notice. Maybe he notices and doesn’t care. Either way, I got both snipers. Put five rounds through those windows in about 6 seconds. Both krauts dropped. Pollson’s still dead. But maybe the next guy lives because I didn’t follow orders. I can live with that. Court marshall can’t live with another Eddie Ramos.

Despite Major Vix’s directive, the matchstick site remained in widespread use throughout the 350th Infantry Regiment until the end of the war. Officers stopped reporting it. Inspectors stopped looking for it. The unofficial policy became, “Don’t ask, don’t tell, don’t die unnecessarily.” The results speak through statistics. September November 1944.

- KIA from sniper fire stick in widespread illegal use. Projected casualties without modification based on June pre-stick rates. 58 KIA lives saved by unofficial continuation of banned modification. 36 men. These 36 soldiers went home to Cleveland and Boston and San Diego and Chicago.

They got married, had children, worked jobs, lived lives. All because officers ignored orders and soldiers broke regulations and nobody cared more about paperwork than people. The army never officially adopted the matchstick site. Never incorporated it into training manuals. Never issued it through supply channels. never acknowledged that a tool and die worker from Youngstown had solved in one evening a problem that professional weapons designers had failed to address for half a century.

Do I regret my recommendation? That’s a complicated question. At the time, I believed I was upholding necessary standards. The military runs on regulations. Without them, you have chaos. But I’ve had 40 years to think about it. 40 years to read the casualty reports. 40 years to calculate how many men might have survived if id recommended adoption instead of prohibition. The number keeps me awake sometimes. Private Kovatch was right. I was wrong.

Not about regulations in general. We need those. But about knowing when to break them. about understanding that the purpose of regulations is to preserve life. And when regulations prevent that purpose, they become obstacles rather than tools. I wrote letters to three mothers after the war.

Women whose sons died in Italy in September 1944. Sniper casualties. I didn’t tell them that their boys might have lived if id put effectiveness over orthodoxy, but I thought about it every time I signed my name. Tommy survived the war. Came home to Youngstown in December 1945, put his uniform in a closet, and never wore it again.

Returned to his job at the Tool and Dye shop on Market Street, married Rose Petrachelli in 1947. had three daughters, worked the same lathe for 37 years until the plant closed in 1982. He never talked about Italy, never joined the VFW, never attended reunions. When his daughters asked about the war, he’d say, “I did my job and came home. That’s all there is to it.

” But in his workshop in the basement, among the calipers and micrometers and drill bits, he kept a 3-in piece of oak wood in a small wooden box. No label, no explanation, just the stick. His daughter, Jennifer, found it after he died in 1994. She didn’t know what it was until she contacted the 88th Division Association and described it.

A veteran named Vincent Delgado called her back. That’s your father’s sight. Delgato said, “That little piece of wood saved my life. Saved a lot of lives. Your dad never told you. He never told us anything.” That’s because the men who really do something important in war are usually the ones who don’t talk about it afterward. the ones who make it home and just want to forget.

Your father was one of the good ones. The matchstick site never entered official military doctrine, but the principle behind it, simplifying sight picture for rapid target acquisition, influenced post-war optics development. Red dot sites, holographic sites, reflex sites, all solve the same problem Tommy identified in 1944. Frame the target squeeze.

The difference is that modern optical sites cost hundreds of dollars and require military contracts and procurement processes and years of development. Tommy’s solution cost nothing and took 20 minutes to make with a knife and a stick. The story of Tommy Kovage and his forbidden rifle site isn’t really about rifles or sights.

It’s about the eternal tension between innovation and regulation between the soldier in the field who sees the problem and the bureaucrat in the office who enforces the rules. Every modern military faces this tension. New doctrine takes years to implement while combat situations evolve weekly. Soldiers improvise solutions. Regulations prohibit improvisation. People die while committees debate.

The match stick site proves that sometimes the best military technology isn’t developed in laboratories or proving grounds. Sometimes it comes from a tool and die worker who knows how to align metal stock, who’s buried three friends, who cares more about bringing his squad home than about following regulations written by people who’ve never smelled guns smoke or heard a bullet crack past their head.

The men who survived because of Tommy’s stick went home and lived full lives. They became fathers and teachers and engineers and shopkeepers. Their children grew up. Their grandchildren were born. All because one soldier looked at a failed system, broke the rules, and made something better with his hands. That’s not military history. That’s human history.

That’s the story worth remembering. The next time someone tells you that regulations exist for a reason and exceptions create chaos, remember Tommy Kovage. Remember that 36 men came home because officers looked the other way and soldiers kept using a banned device. Remember that sometimes the right thing to do is the forbidden thing.

History isn’t made by people who follow orders. It’s made by people who follow their conscience and accept the consequences. If this story moved you, share it. Tell it to someone who needs to hear that doing the right thing sometimes means breaking the rules. Tell it to someone who works in an organization so bound by regulations that effectiveness dies while paperwork multiplies.

And if you’re the person making the rules, remember Major Vicks. Remember that he spent 40 years regretting his decision, remember that regulations serve people, not the other way around. Tommy Kovatch never wanted recognition, but his story deserves to be told. Share this video. Leave a comment about someone you know who broke the rules for the right reasons.

Hit subscribe if you want more stories about the forgotten heroes who changed history with nothing but courage and a piece of wood. Because that’s all it takes sometimes.