March 1943. Over the Mediterranean, a German ace lines up the kill. His wingman closes the trap. Between them, a lone American pilot in a battered P40. No altitude, no speed, no way out. Then he does something no one has ever seen before. Something the manuals never taught.

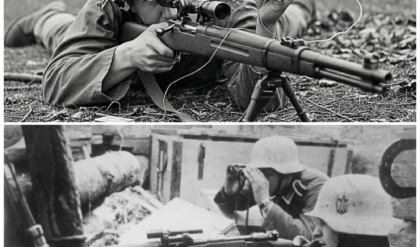

Something that will rewrite the rules of air combat forever. Spring 1943. The Mediterranean theater bleeds Allied pilots at a terrifying rate. German Mesosmmitz and Italian Machi fighters dominate the skies over North Africa and Sicily. Their pilots are veterans blooded over France and Russia, masters of energy tactics and vertical combat. They hunt in coordinated pairs, exploiting altitude and speed with surgical precision.

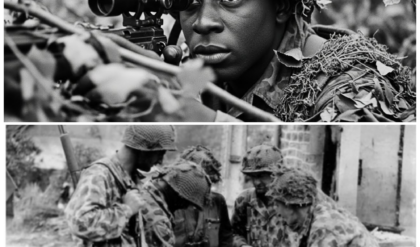

American pilots arrive in waves. Most are fresh from stateside training programs. Their log books thick with hours but thin with wisdom. They fly P40 Warhawks, tough aircraft, but outclassed in climb rate and ceiling. The math is brutal. In the first months of North African operations, Allied fighter losses exceed replacements.

Squadrons cycle through pilots like infantry through riflemen. The smell inside a P40 cockpit is engine oil and sweat. The Mediterranean sun turns the metal shell into an oven. Pilots wear leather jackets not for warmth, but to protect skin from burns when they touch the frame. The stick vibrates constantly.

The Allison engine roars 6 ft ahead, throwing heat and fumes back through the firewall. Visibility is limited. The long nose blocks the view forward. Combat becomes a frantic scan. Neck craning, eyes watering from strain and altitude. Tactical doctrine is clear. Maintain altitude. Never turn with an enemy fighter. Use speed to disengage. Fight in pairs. Protect each other. The rules are written in blood.

Refined over two years of European combat. They work. When pilots follow them, survival rates improve. When they deviate, they die. But doctrine assumes rough par. It assumes you can choose when to engage. Over the Mediterranean in early 1943, Allied fighters rarely have that luxury.

They fly escort missions for bombers, cargo planes, reconnaissance birds. They cannot run. They cannot choose. When German fighters bounce them from above, they absorb the first attack and try to survive long enough to scatter the enemy. Most do not. The vertical tactics of the Luftvafa are devastating. A Messmitt dives from 20,000 ft, builds speed to over 400 mph, closes to firing range in seconds. The P40 pilot sees him too late.

The cannon shells walk up the fuselage. Fire blooms. The aircraft tumbles, trailing smoke and pieces, and the sky moves on. Between missions, pilots sit in the shade of wing roots and talk in quiet voices. They compare notes. They sketch diagrams in the sand. They argue about deflection angles and energy states.

Some believe the solution is better equipment. Others want more training. A few think the war in the air is simply unwinable with what they have. All of them are exhausted. All of them have seen friends burn. Ground crews work through the night, patching bullet holes, replacing shattered canopies, scrubbing blood from seats.

They do not speak of what they clean. Mechanics develop superstitions. Some refuse to work on a plane that has lost two pilots. Others inscribe small symbols on engine cowlings prayers in grease pencil. Everyone knows the statistics. Everyone pretends they do not. In officers tents, intelligence summaries tally the losses. Graphs show kill ratios.

Reports recommend tactical adjustments. Commanders send cables requesting better aircraft, more fuel, longer training cycles. The replies are sympathetic but vague. Everyone is short of everything. The war is global. Resources flow where they are most needed. The Mediterranean is a secondary front. The pilots make do.

And then a small town pilot with a quiet draw and a habit of sketching in notebooks starts asking questions no one else thinks to ask. If this history matters to you, tap like and subscribe. His name is Lance Wade. Born in a small Texas town, raised on stories of barntormers and air mail routes. He learns to fly in his teens, trading work for lessons at a dusty airirstrip outside Bris.

No money, no connections, just an obsession with the mechanics of flight. He reads everything he can find. textbooks on aerodynamics, manuals on engine performance, articles about racing pilots and their modifications. Wade is not a natural. He is methodical. He approaches flying the way a machinist approaches a lathe with patience and precision. He does not trust instinct. He trusts math.

He keeps a log book not just of hours but of conditions, wind speed, temperature, aircraft weight, fuel load. He notes how each variable changes performance. He develops a sense for the edges of an aircraft’s envelope, the margins where control begins to soften and physics takes over. When war breaks out in Europe, Wade tries to enlist in the Army Airore.

He is rejected. Poor eyesight. Correctable, but the standards are strict. He tries again. Rejected again. Frustrated, he hears about a British program recruiting American pilots. The Royal Air Force is desperate. Their standards are lower. Wade volunteers.

In late 1940, he sails for England, one of dozens of Americans who will fly for the RAF before the United States enters the war. Training is abbreviated. The British need pilots in the air, not in classrooms. Wade is assigned to a fighter squadron, then another, then shipped to North Africa in early 1942. He flies hurricanes first, then P40s when American aircraft begin arriving in theater.

His squadron mates are a mix of nationalities, British, South African, Australian, Rhodesian, American. They call themselves the desert air force. They are tired and understaffed and constantly outnumbered. Wade does not stand out at first. He is quiet, polite, unassuming. He does not boast or tell stories in the mess tent. After missions, he disappears to his tent and writes not letters, notes.

He sketches the geometry of dog fights from memory, drawing arcs and vectors, estimating speeds and angles. He is trying to understand something that eludes most pilots. The pure physics of air combat. Most pilots think in terms of maneuvers. Break left, split S, Chandel. Wade thinks in terms of energy states, potential energy, kinetic energy, the conversion of altitude into speed, the cost of turning in terms of velocity bled away. He begins to see patterns that others miss.

He realizes that doctrine is not wrong but incomplete. It teaches what to do but not why. It does not explain the underlying mechanics. He starts experimenting. small things at first. Adjusting his throttle settings during climbs to find optimal rates. Testing how much he can tighten a turn before the aircraft shutters into a stall.

Pushing the limits in training flights alone where mistakes will not cost a wingman’s life. His ground crew notices the wear on his aircraft. Tires scuffed from hard landings. Paint scraped from wing tips. The crew chief asks if everything is all right. Wade says he is learning the airplane.

The crew chief does not ask again. WDE’s squadron leader is a by the book officer, a veteran of the Battle of Britain. He values discipline and formation integrity. He does not encourage freelancing. When Wade begins asking technical questions during briefings, the leader answers curtly. Doctrine exists for a reason. Pilots who deviate die. The discussion ends there. But Wade keeps thinking.

He cannot shake a growing conviction that something fundamental is being missed. The P40 is slower than a messmitt. It climbs worse. It cannot outrun or outclimb the enemy. Doctrine says to avoid turning fights. But what if that is exactly wrong? What if the one place the P40 has an advantage is the place no one is looking? He knows the numbers.

A P40 can sustain a tighter turning radius than a messes at certain speeds. It has a lower wing loading, better low-speed handling. In a flat grinding turn, it might outturn the German fighter, but doctrine says never to try. Turning bleeds speed. A slow aircraft is a dead aircraft. Every manual agrees.

Every instructor teaches it. Every combat report reinforces it. Wade starts to wonder if everyone is wrong. The problem is not new. Since 1940, Allied pilots have faced faster, better climbing German fighters. The Spitfire solved the issue through performance par. The P40 does not have that option. It is a pre-war design optimized for ground attack and lowaltitude work.

Against modern fighters, it is overmatched. Losses mount. By mid 1943, some P40 squadrons report 50% turnover every two months. New pilots arrive, fly a handful of missions, and disappear. The veterans grow holloweyed. They stop learning names. They stop attending memorial services. There are too many. Tactical adjustments are attempted.

Squadrons try flying in larger formations for mutual support. It helps, but only marginally. The Luftwaffa adapts, using altitude and surprise to split formations before they can respond. Some units experiment with defensive circles, each pilot covering the tail of the plane ahead. It works against single attackers but collapses under coordinated assault.

Engineers propose modifications. Armor plating is added. Self-sealing fuel tanks become standard. Gun sites are upgraded. None of it changes the fundamental equation. The P40 is still slower. The enemy still dictates the terms of engagement. Allied pilots still die at unacceptable rates.

Training programs expand, but results are mixed. Pilots learn aerobatics, formation, flying, gunnery. They practice dive attacks and slashing passes, but training happens in safe skies at medium altitudes without fear. Combat happens in chaos, in three dimensions, with death measured in seconds. The gap between classroom and cockpit is unbridgegable.

Some pilots break under the strain. They develop tremors, insomnia, sudden rages. Flight surgeons ground them quietly. Others grow reckless, taking suicidal risks, eager to end the waiting. A few simply refuse to fly. Courts marshall are rare. Everyone understands.

The question is not why some men break, but why more do not. And through it all, the doctrine remains unchanged. Maintain speed. Avoid turning. Disengage when possible. The rules are carved in stone because no one has found a better answer. No one has proven an alternative. The cost of experimentation is death, and death is already too common. But Wade cannot stop thinking about energy.

He lies awake in his tent, listening to the wind snap the canvas, running equations in his head. He knows a turn costs speed, but speed can be regained. A tight turn imposes G forces, but the human body can endure G’s. A slow aircraft is vulnerable, but only if the enemy can bring guns to bear, and if the turning radius is tight enough, the enemy cannot.

He begins to visualize a maneuver. It forms slowly across weeks of thought and sketches. A hard descending turn initiated at the moment of attack. Not a gentle break. Not a standard defensive spiral. Something more violent. A full deflection pull. Maximum G bleeding speed deliberately to tighten the radius. The goal is not to escape. The goal is to reverse the geometry.

To turn inside the attacker’s ark, to make the enemy overshoot, it requires perfect timing. Too early and the attacker adjusts. Too late and the cannon shells arrive first. It requires trusting the aircraft at the edge of a stall. It requires ignoring every instinct that screams to keep speed, to run, to survive by fleeing. It is the opposite of doctrine.

It is suicide unless it works. Wade has no way to test it safely. Training flights do not simulate an attacker diving at 400 mph. No friendly pilot will press a mock attack that close. The only way to know is to try it in combat. And if he is wrong, he will not get a second chance. He thinks about telling his squadron leader.

He drafts the explanation in his mind, but he already knows the response. Doctrine exists for a reason. Pilots who deviate die. He would be ordered to stop. He would be grounded for his own safety. The idea would die with him. So he says nothing. He files the maneuver away. A theoretical answer to an impossible problem. He continues flying standard missions. He follows the rules.

He survives and he waits for the moment when survival will not be enough. March 1943. Wade is flying escort for a transport run over the Mediterranean. His flight consists of four P40s strung out in a loose formation scanning the sky. The transport lumbers below, heavy and slow. The mission is routine.

The radio chatter is sparse. Then the call comes. Bandits high. 2:00 diving. Wade looks up and sees them. Two messes in a classic bounce. Sunlight glinting off their canopies. They are fast. They are committed. And they have chosen Wade as their target. His wingman breaks left. The other two P40s scatter.

Wade is alone. The Messor Schmidts split. One high, one low. A vertical pinser. Standard tactic. No escape. WDE’s hand tightens on the stick. His mind goes quiet. The fear is there, but distant. He is calculating. Speed, angle, closure rate, time. The leader attacks first, diving from above.

Wade sees the muzzle flashes. Tracers arc toward him, lazy and bright. He has perhaps two seconds. His training tells him to dive, to run, to use gravity to build speed. His instinct tells him the same. Every fiber of his body wants to push the stick forward and flee. Wade pulls back instead hard. Full elevator. The stick comes into his lap. The nose pitches up.

The horizon spins. The G forces slam him into his seat. Blood drains from his head. His vision tunnels. The engine shrieks. The wings flex. The aircraft shutters on the edge of a stall and the world rotates. The messes flashes past too fast, too committed. It cannot turn inside WDE’s ark.

It overshoots, nose high, energy bleeding as the pilot tries to reacquire. Wade rolls out, still slow, still vulnerable, but no longer in the line of fire. He has reversed the attack. The hunter has become the hunted. The second Messor Schmidt is still diving. Wade has no speed. He cannot run. He pulls again. Same maneuver, same violence.

The aircraft bucks and groans. The stall warning rattles. His vision grays. He holds the turn. The second messes overshoots. Wade rolls wings level. Both attackers are ahead of him now, climbing, trying to regain position. Wade is slow. He is low, but he is alive. The messes do not press the attack.

They climb away, unwilling to descend again into the same trap. Wade lets them go. He has no fuel to pursue. He has no speed to catch them. He turns back toward the transport, his hands trembling on the stick, his heart hammering. He has just done something that should have killed him, and it worked. He lands in silence.

His ground crew inspects the aircraft. No damage, no hits. WDE climbs out, legs unsteady. The crew chief asks if he saw action. Wade nods. He does not elaborate. He walks to his tent and sits on the edge of his cot. He pulls out his notebook. He sketches the encounter from memory. Every angle, every second.

He writes a single word at the bottom of the page, repeatable. But the squadron leader does not see it that way. Wade files a combat report. The leader reads it, frowns, and calls Wade into his tent. He asks Wade to explain the maneuver. Wade tries. He talks about turning radius, about energy exchange, about geometry. The leader listens with growing frustration.

He tells Wade he got lucky. He tells him the maneuver is reckless. He tells him not to try it again. Doctrine exists for a reason. Pilots who deviate die. Wade says nothing. He salutes. He leaves. He knows what he experienced. He knows it was not luck. But he also knows he cannot convince anyone with words. He needs proof. He needs repetition. He needs other pilots to see it work.

So he keeps flying and he keeps waiting. April 1943. Another mission, another bounce. This time Wade is ready. The moment the messes commits, Wade pulls. The same violent turn, the same edge of stall arc, the same overshoot. This time, Wade has enough speed remaining to reverse again.

He pulls into a climbing turn, tracking the Messersmidt as it tries to escape. He fires. Tracers converge. The messes trails smoke. Wade does not follow. He turns back to the formation. Another encounter. Another survival. May 1943. A third engagement. This time WDE’s wingman sees the maneuver. After they land, the wingman asks how Wade did it. Wade explains slowly, carefully.

He draws diagrams in the sand. He talks about timing, about when to initiate the pull. The wingman listens. The next mission when they are attacked, the wingman tries it. He overshoots his first attempt, pulling too early, but he survives. On the next engagement, he gets the timing right. He forces an overshoot. He lives. Word spreads. Other pilots ask questions.

Wade begins informal briefings, sketching on scraps of paper, demonstrating with his hands. Some pilots are skeptical. Others are desperate enough to try anything. Gradually, quietly, the maneuver begins to circulate through the squadron. It has no official name. Pilots call it WDE’s turn. Some call it the last ditch break.

A few call it suicide with a chance. The squadron leader hears about it. He is furious. He calls Wade in again. He threatens to ground him. Wade listens calmly. Then he asks a simple question. How many pilots have survived using the maneuver? The leader does not have an answer. Wade provides one, seven pilots, eight engagements, no losses.

The numbers speak. The leader dismisses him without further comment, but he does not issue the grounding order. June 1943, a larger engagement. A German fighter grouper bounces an entire Allied squadron, 12 P40s against 20 Messids. The radio erupts with calls. Pilots scatter. The sky fills with tracers and smoke.

Wade pulls his maneuver twice, forcing overshoots, staying alive around him. Other pilots do the same. The Luftwaffer, accustomed to easy kills, suddenly faces targets that refuse to cooperate. Attacks that should succeed fail. Firing solutions that should be simple evaporate. Confusion spreads. The engagement lasts 8 minutes. When it ends, three P40s are lost, but nine return.

In previous engagements of similar size, losses averaged 50%. This time 75% survive. The math is undeniable. Something has changed. Afteraction reports reach higher command. Intelligence officers take note. A flight instructor is sent to interview Wade. The instructor is skeptical. He asks Wade to demonstrate. Wade takes him up in a two seat trainer.

He simulates the maneuver at altitude, slow and controlled. The instructor experiences the G’s, the buffet of the stall, the violence of the pull. He lands pale and quiet. He files a report recommending further evaluation. A formal test program is initiated. Pilots volunteer to act as attackers and defenders. Wade teaches the maneuver in structured sessions. Engineers measure the turning radius, the G- loads, the speed loss.

They confirm what Wade intuited. At specific speeds, the P40 can outturn a messes by a significant margin. The cost is speed, but the gain is survival. Doctrine is quietly updated. No official announcement, no public reversal, but the training syllabus is modified.

New pilots are taught the defensive break as a last resort tactic. Instructors emphasize timing and aircraft control. The maneuver is paired with situational awareness, ensuring pilots know when to use it and when to flee. It is not a replacement for sound tactics. It is an additional tool, a final option. By summer 1943, the maneuver has spread beyond Wade’s squadron. Pilots across the Mediterranean theater are using it.

Some modify it, adding rolls or vertical components. Others combine it with other tactics, using the break to set up counterattacks. The Luftvafa begins to adapt, becoming more cautious in their attacks, wary of overshooting, but caution slows them. It disrupts their aggression, and that alone saves lives. WDE’s personal tally grows.

By August, he is credited with eight confirmed kills. Not through aggression, through survival. Through turning a defensive maneuver into an offensive opportunity. He is promoted. He is given a flight to command. He continues flying. He continues teaching. He does not seek recognition. He seeks results. By late 1943, Allied air superiority over the Mediterranean begins to shift.

It is not due to one factor. New aircraft arrive. P-51 Mustangs Spitfire Mark 9. Pilot training improves. Logistics strengthen. But in the crucial months of mid 1943, when the balance hung on a knife’s edge, one maneuver made a measurable difference.

Statistical analysis conducted after the war shows that P40 loss rates in the Mediterranean dropped by 18% between April and August 1943. Intelligence reports from captured Luftvafa pilots mention Allied fighters using unexpected defensive tactics. German training manuals are updated to warn against overcommitting to attacks on P40s. The ripple is subtle but real. More than numbers, the maneuver changes mindset. Allied pilots stop seeing themselves as victims.

They stop accepting inferiority as inevitable. They learn that even outmatched aircraft can fight back, that physics and courage can compensate for performance gaps. Morale improves. Confidence grows. Pilots fly more aggressively knowing they have an option if an engagement turns bad.

Wade himself becomes a quiet legend. He is not flashy. He does not seek fame, but pilots talk about him. They repeat stories of the small town Texan who rewrote the rules. Some of the stories are exaggerated. Most are not. By the end of 1943, Wade has flown over 200 combat missions. He has 13 confirmed kills. He has never lost a wingman.

In January 1944, Wade is transferred to a P-47 Thunderbolt squadron. The P-47 is a brute, a heavy fighter with power and armor. It does not need WDE’s maneuver. It overpowers opponents. But Wade continues to fly with the same methodical precision. He continues to teach. He continues to think about energy and geometry.

He is studying bomber escort tactics, looking for inefficiencies. When his aircraft suffers engine failure on a routine flight, he crashes on takeoff. He is killed instantly. He is 28 years old. The news spreads quietly through the squadrons. Pilots who knew him attend a service in a dusty field outside Naples. There is no ceremony. A chaplain says a few words. A bugler plays taps.

The war moves on. WDE’s name appears in casualty lists, one more among thousands. There is no medal, no official commenation, no mention of the maneuver that saved dozens of lives. But the maneuver survives. It becomes part of the unofficial cannon of fighter tactics passed pilot to pilot, squadron to squadron. After the war, aviation historians begin documenting combat innovations.

WDE’s defensive break is analyzed in technical journals. Test pilots recreate it in modern aircraft. It becomes a case study in energy management, a lesson in how to fight from disadvantage. In the 1950s, the maneuver is formalized in US Air Force training as a high G defensive break.

It is taught to jet pilots facing faster misalarmed adversaries. The principles remain unchanged. Sacrifice speed to tighten radius force and overshoot reverse the geometry. The names of those who use it are recorded. The name of the man who invented it is mostly forgotten. Today, fighter pilots around the world learn variations of WDE’s maneuver.

It appears in training doctrine under different names, stripped of its origin story. The physics are well understood now. Computers model turning performance. Simulators replicate the G forces, but the core insight remains WDs. That survival sometimes requires doing the opposite of what instinct and training demand. Lance Wade’s grave is in a military cemetery in Italy. Few visitors stop.

There is no statue, no plaque explaining his contribution. The historical record is sparse. A handful of combat reports, a few paragraphs in unit histories, scattered mentions in memoirs of pilots who flew with him. The full scope of his impact was never documented because he died before the war ended and because the men he saved scattered to other squadrons, other theaters, other lives. But physics does not forget.

The equations he understood still govern flight. The principles he demonstrated still apply. In the archives, his sketches remain precise diagrams of arcs and vectors, a quiet testament to a mind that saw past doctrine to deeper truth. War is often remembered through grand strategies and decisive battles, through generals and politicians, through the sweep of armies and the clash of fleets.

But wars are also shaped by individual moments of clarity, by a pilot alone in a cockpit calculating angles while death dives toward him, by the choice to trust logic over fear, to test an idea that everyone else dismissed. Wade did not seek to be a hero. He sought to solve a problem. He approached air combat the way he approached everything, methodically, patiently, with respect for the underlying mechanics. He did not invent courage. He did not discover some secret weapon.

He simply looked at the same situation everyone else faced and asked a different question. Not how to run faster, but how to turn tighter. Not how to avoid the fight, but how to survive it. The lesson is not that one man changed the war. The lesson is that one man thinking clearly under pressure found a margin of advantage that others missed.

And that margin multiplied across hundreds of engagements across dozens of pilots became the difference between loss and survival, between despair and hope. between a doctrine that accepted defeat and a tactic that demanded something better. Wade’s story is a reminder that innovation does not always come from laboratories or high commands.

Sometimes it comes from the edge of a stall, from a pilot willing to trust his calculations more than his fear. from a quiet voice asking uncomfortable questions. From the stubborn belief that there must be another way, and the courage to prove it when no one else will. The skies over the Mediterranean are peaceful now. The wreckage has long been cleared. The air bases are silent or repurposed.

The men who flew and fought there are nearly all gone. But the principles remain encoded in training manuals passed through generations of pilots who will never know the name of the small town Texan who first pulled that desperate defiant turn. Some legacies are carved in stone. Others are written in the physics of survival, in the unspoken knowledge that when the world compresses to seconds and tracers, there is always one more option, one more calculation, one more chance to turn inside the enemy’s ark and prove that disadvantage is not destiny. That logic and courage combined

can reshape the geometry of war itself. Wade did not live to see the end, but his idea did.