Bavaria, April 1945. Morning mist clung to the valley like smoke, turning pine forests into ghosts, obscuring the road where company B trudged forward through mud that sucked its boots. Lieutenant James Morrison heard at first a sound that did not belong in this landscape of war.

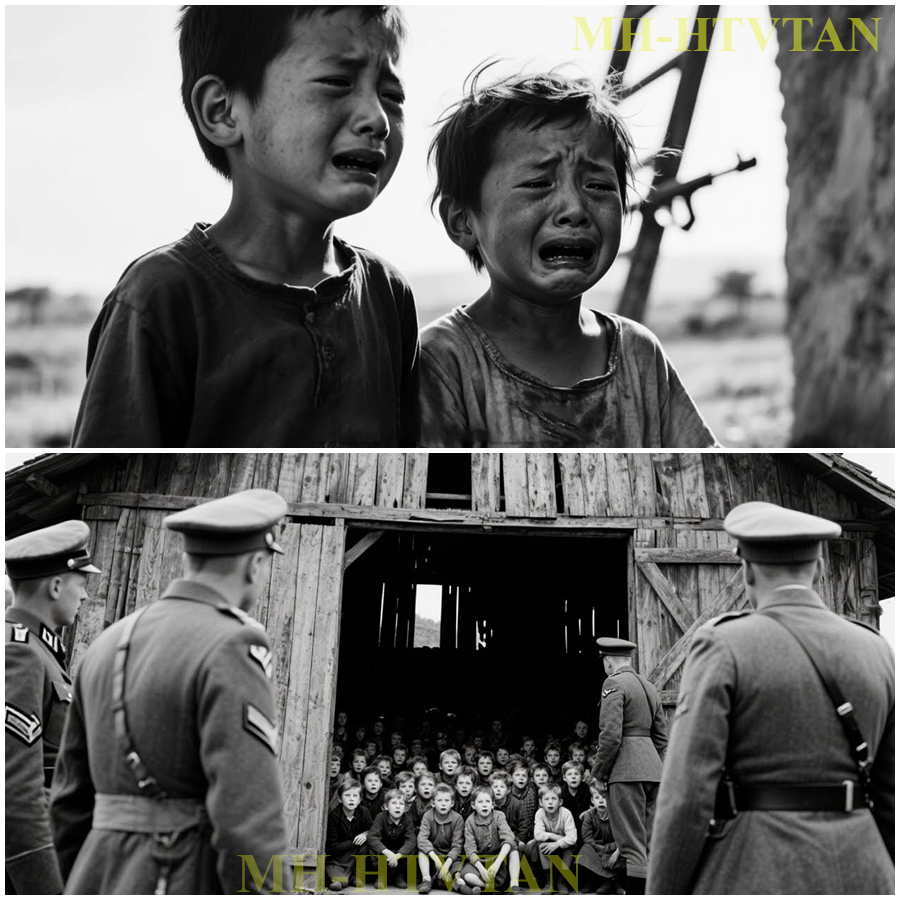

Not gunfire or engines, but something thinner, higher, children crying. His platoon stopped, rifles raised, listening to the April silence. The barn stood alone in the meadow, ancient woods silvered by weather, listening to one side like something too tired to stand. Inside, 200 German children huddled in darkness, waiting to die. What the Americans did next would challenge every assumption about enemies and innocence, about war and mercy, about what soldiers carried besides weapons. The advance through Bavaria had been slow, methodical, village by village. Company

B of the 45th Infantry Division moved through landscape that seemed untouched by time medieval. Church spires rising above stone houses, forests so thick they blocked sunlight, streams running clear over rocks worn smooth by centuries. But the war had been here. Evidence lay everywhere.

abandoned artillery pieces rusting in fields, craters where bombs had fallen, houses with walls blown out, exposing rooms like dollhouse cutaways, furniture still arranged, as if families might return any moment. Lieutenant Morrison was 24 years old from Oregon, a school teacher before the war.

He had landed at Solerno, fought through Rome, crossed the Rine, seen things that would wake him at night for decades. He knew how to read terrain, how to sense ambush, how to keep his men alive, but he did not know what to do with the sound of children crying in an abandoned barn. Sergeant Tom Carter moved beside him, rifle ready.

Carter was older, 32, a farmer from Iowa who had three children of his own back home. He looked at Morrison, waiting for orders. “Could be a trap,” Carter said quietly. Morrison nodded. They had found traps before buildings rigged with explosives. Civilians used as shields, desperate last stands by forces that knew they were losing. But the crying continued, thin and desperate.

The sound of fear so pure cut through tactical thinking. Perimeter, Morrison ordered. Williams checked the barn. Careful. Private Eddie Williams approached slowly, rifle raised, moving with the careful deliberation of a man who had survived 11 months of combat by never assuming anything was safe.

He reached the barn door, pressed his ear against weathered wood, listened. The crying grew louder, punctuated by German voices, adult voices trying to soothe, to comfort, to maintain order in whatever chaos existed inside. Williams pushed the door open. Sunlight streamed into darkness, illuminating a scene that made him lower his rifle. Children, dozens of them.

Hundreds packed into the barn like livestock, sitting on hay bales, huddled against walls, held in the arms of women whose faces showed exhaustion, so complete it bordered on death. The children ranged from infants to teenagers, dressed in clothes that had once been fine, but now hung in tatters, faces stre with dirt and tears, eyes wide with terror. A woman stood, blocking the children with her body.

She was perhaps 40, tall and thin, wearing what had once been a teacher’s dress, now stained and torn. Her hands trembled, but her voice was steady. “Please,” she said in broken English. “Please, they are only children.” William stood frozen, his rifle hanging loose.

He had stormed beaches, cleared houses, fought through streets where enemies hid in every shadow. He had been trained to destroy resistance, to eliminate threats, to win. But this was not the enemy. This was 200 terrified children crying in a barn. He turned, called back to Morrison. Lieutenant, you need to see this. Morrison entered the barn slowly, letting his eyes adjust to the dimness.

The smell hit him first unwashed bodies, fierce, sweat, soiled clothing, and beneath it all the sweet rot of infection and illness. Children watched him with eyes that had seen too much, faces that carried the particular emptiness of those who had stopped believing in safety. Four women stood among the children, forming a protective barrier with their bodies. The one who had spoken stepped forward again.

I am Fruine Greta Schneider, she said, each English word carefully formed. Teacher, these are children from Cologne. We evacuate when the bombs come. We walk for weeks, many weeks. The others, a dot dot doppel, she trailed off, unable or unwilling to finish. Morrison holstered his pistol, raised his hands to show they were empty. I’m Lieutenant Morrison, United States Army. How many children? 207.

Greta said, “Ages 3 months to 14 years. We have no food for 3 days. Water.” Dot dot dot. She gestured to a few buckets that held maybe a few inches of muddy liquid. We find stream yesterday. Carter had entered behind Morrison, and now he moved through the barn, counting heads, assessing the situation with the practiced eye of a man who had raised livestock and children in equal measure. Some kids slept fitfully on hay piles.

Others sat in silent groups, too exhausted for tears. A few of the older ones held infants, rocking them with the mechanical persistence of those who had been doing it for days. Jesus Christ,” Carter whispered. Morrison turned to find Corporal Ramirez, the company medic, a man from New Mexico who had sewn up more wounds than he could count. “Get up here. Bring everything we have.

” The other teachers introduced themselves. “Frewine Hartman, a young woman barely 20, who taught music. Frine Ko, older, gay-haired, a mathematics instructor. and Frame Meyer, a widow who had taught literature before the war took her husband and both sons. They had been evacuating children from Cologne since March, moving them away from Hali bombing, away from advancing armies, searching for safety that did not exist.

The city was destroyed, Greta explained, sitting on a hay bale, while Morrison’s men began distributing cantens of water. First British bones, then American. The school, my school, it fell collapsed. We save the children, bring them out. The parents, they beg us, take them somewhere safe. So we walk first to Dresden. She paused, her face going still. Dresden was worse.

Morrison knew about Dresden. Everyone knew about Dresden. The firestorm that had consumed the city in February. temperatures so hot that people had been incinerated in basements where they hid. The entire company had heard reports seeing the aerial photographs. Estimates ranged from 25,000 to over a 100,000 dead, though no one knew for certain because there were not enough remains to count. “We leave before the fires,” Greta continued. “Take the children south.

We think maybe Bavaria will be safe. But everywhere we go, the war follows. Villages will not take us too many mouths, not enough food. Some places they chase us away with sticks. So we walk, always walking. Ramirez moved among the children, checking for immediate medical crisis. He found malnutrition, dehydration, lice, infected wounds, respiratory infections, and in three cases, symptoms that might be typhus or dysentery.

But none were dying. Not yet. The teachers had somehow kept them alive through weeks of displacement, starvation, and exposure. How? Morrison asked quietly, watching Fula and Hartman comfort a crying infant. How did you keep them alive? Greta looked at him with eyes that held something beyond exhaustion.

Because we promised the parents, when they give us their children, they make us promise. Keep them safe. Bring them home when the war ends. So we promise, and a promise, dot dot dot. She searched for words. A promise is all we have left. Morrison stood outside the barn, smoking a cigarette he did not want, trying to think through options that felt like choosing between bad and worse.

The tactical situation was clear company B was advancing east, pushing toward Munich, following orders that had been written by generals who calculated war in terms of objectives achieved and territories secured. 200 German children did not appear in those calculations. Carter joined him, accepting a cigarette. What are we going to do, Lieutenant Morrison exhaled smoke toward gray sky? Protocol says we reported up the chain. Wait for instructions from regiment.

How long will that take? Could be hours. Could be days. Morrison looked back at the barn. Those kids don’t have days. Private Williams approached carrying a clipboard. Did a count, sir. 207 children, like the teacher said, we gave them all the water we could spare, distributed some rations. Ramirez says at least a dozen need medical attention soon, maybe three or four critically.

Morrison nodded, making calculations. The company had field rations for 3 days, medical supplies for minor wounds and common ailments. They were not equipped to care for 200 starving, sick children. But leaving them was not an option. Could not be an option. What about the rest of the advance? Williams asked. That was the question.

Company B had orders secure the next village, establish a defensive position, wait for armor support before pushing toward Munich. Delays meant the entire battalion schedule would be affected. Resources diverted. plans changed and wars were won by following plans, by maintaining momentum, by not letting sympathy interfere with objectives.

Morrison thought of his classroom back in Oregon, the students he had taught before the war. 12year-olds learning geography, struggling with long division, passing notes when they thought he was not looking, children being children, blessed with the ordinary cruelty and kindness of youth untouched by war. He dropped the cigarette, grounded out with his boot. “We’re taking them with us,” Carer raised an eyebrow.

“Sir, we’re taking them with us,” Morrison repeated louder now, his voice carrying the edge of decision made. “All of them? The teachers, too. We’ll radio regiment explain the situation, but we’re not waiting for permission. Those kids need food, water, and medical care now. We’ll bring them to the next village, set up a temporary facility, get them stabilized.

A captain’s not going to like this, Carter said. But he was already smiling, the expression of a man who had hoped his lieutenant would make exactly this decision. A captain can court marshall me if he wants, Morrison said. But I’m not leaving children to die in a barn. They moved out at noon. a column that bore no resemblance to any military formation Morrison had ever commanded.

Soldiers carried children who were too weak to walk. Jeeps were loaded with the youngest. Infants and toddlers piled carefully among ammunition crates and radio equipment. The teachers walked alongside trying to maintain order, singing German songs to keep spirits up, to distract from hunger and exhaustion.

The Americans shared their rations, chocolate bars from Krations, crackers, canned peaches that were divided with mathematical precision to stretch as far as possible. Some soldiers gave away their entire day’s food, figuring they could eat later, and children needed it more.

Private Johnson, a mechanic from Detroit who never talked about having kids, carried a three-year-old girl on his shoulders for six miles. Whispering to her in English, she did not understand, but found comforting anyway. Sergeant Carter walked beside Greta Schneider, helping her navigate the muddy road.

She limped feet wrapped in cloth that had once been a skirt worn through to bleeding, but she did not complain. “Why are you doing this?” she asked. We are German enemy. Carter shifted the pack on his shoulders. My youngest is four back in Iowa. Little girl named Sarah. He paused, remembering, “If the war came to Iowa, if she was scared and hungry and hiding in a barn, I’d hope someone would help her. Even if they were the enemy.

” Greta said nothing, but tears carved lines through the dirt on her face. The column moved slowly, stopping frequently for rest, for water, for children who could not continue. Some of the older kids helped the younger ones, carrying siblings or neighbors, acting as shepherds to flocks of frightened lambs. An 11-year-old boy named Hans appointed himself translator.

His English learned from a grandfather who had lived in America before the first war. He moved between soldiers and children, explaining needs, facilitating communication, trying to maintain dignity in circumstances that had stripped away nearly everything else. By midafternoon, they reached the village of Burkeling.

It was a small place, maybe 300 residents, clustered around a church with a copper green steeple. White flags hung from windows, the universal signal of surrender of communities that wanted the war to pass them by without destroying what remained. Morrison ordered a halt. Carter, take second squad. Secure the village. Make sure there’s no resistance. I want the church if it’s available, the town square if not.

Somewhere we can gather these kids, get them organized. The village surrendered without incident. The local burgermeister, an elderly man named Harris Schaefer, who spoke passible English, met them at the church steps. He looked at the children filling the square, at the American soldiers carrying toddlers, at the German teachers weeping with relief. “We have no food,” he said, spreading his hands.

“The army took everything. We barely feed ourselves.” Morrison stepped close, his voice low and hard. Then you’ll find some because these children are staying here tonight and they’re going to eat. And if I find out you’ve been hoarding supplies while kids starve, I’ll burn every barn in this village until I find what you’re hiding.

Schaefer pald the church basement, some potatoes, flour, a few chickens. We were saving. Get it. Now the church basement became a makeshift field hospital. Nessall and orphanage combined. Ramirez set up a medical station in one corner, treating the worst cases first infections that needed draining, wounds that needed cleaning, fevers that required monitoring.

The village women, initially reluctant, were conscripted by Schaefer to help prepare food. They made potato soup in quantities that would have fed the village for a week, stretching it with water and flour to feed 200 children. The meal was simple, thin broth with chunks of potato, bread so hard it needed soaking, but the children ate like it was a feast.

Some vomited afterward, their stomachs unable to handle solid food after days of starvation. Others ate slowly, carefully, making every bite last. The youngest fell asleep with bread still clutched in their hands. Morrison sat with Greta Schneider on the church steps, watching sunset paint the sky in shades of orange and purple. Somewhere to the east, artillery rumbled the war, continuing without them, indifferent to this small act of mercy. “What will happen to them?” Greta asked.

Morrison did not have an answer. “We’ll get them stable. Contact refugee services. Try to find their families. if they have families left. Many do not. Brea’s voice was flat, stating fact without emotion. The bombing, the fighting, Cologne is rubble. Dresden is rubble. Hamburg, Berlin, all rubble.

The children, they talk about homes that do not exist anymore. Parents who dot dot dot. She stopped, unable to continue. Morrison thought about his own parents in Oregon, safe in a country that had never been bombed, where children still went to school and played baseball and worried about homework instead of starvation. The distance between those worlds seemed too great to comprehend.

We were told you would be monsters, Greta said quietly. The propaganda, it said Americans were savages who would destroy Germany, who hated us, who wanted only revenge. I believed it at first, but then I see your soldiers giving their food to children who sang songs about their destruction. I see men carrying enemy babies because they cannot walk.

And I think maybe the propaganda lied about many things. Inside the church, someone was singing. One of the American soldiers, a kid from Tennessee with a voice like honey, had started a folk song. Some of the German children were humming along, not knowing the words, but catching the melody. Music that bridged the gap between languages, between enemies, between the world that was ending and whatever came next.

My brother died in France, Morrison said, surprising himself. Normandy, June 6th. I got the telegram 3 days before I shipped out. He paused, finding words for something he had not spoken about since learning the news. I hated Germans. Every single one. Wanted them all to pay for taking my brother.

And then I landed in Italy and I saw German prisoners. Just kids, most of them scared and hungry and crying for their mothers. And I realized they were just like my brother. Just kids who got caught in something bigger than themselves. Greta reached out, touched his hand briefly. I am sorry about your brother. Morrison nodded, throat tight. War makes us all liars.

We tell ourselves stories about good and evil, about us and them, because those stories make it easier to do what we have to do. But then you find children in a barn, and the stories stop working. They sat in silence as night fell, watching stars emerge in a sky that showed no evidence of the hell unfolding below it. Morning brought problems.

Regiment had received Morrison Ezreport and responded with orders that were clear and unambiguous company B would resume its advance immediately. The German children were to be turned over to local civilian authorities and processed as displaced persons according to military government protocols.

Morrison was specifically ordered not to delay the advance for humanitarian concerns that were the responsibility of military government units following behind combat troops. Morrison read the orders twice, then crumpled the paper and threw it in the fire. Sir, Carter asked carefully. We’re not leaving them. Regiment was pretty clear. I don’t care what Regiment said. Morrison stood, pacing the small room in the village in where they had set up temporary headquarters.

We’re 3 days from Munich. The war is almost over. Everyone knows it. I am not going to spend the last days of this war abandoning children because some colonel in a clean uniform says it is not our responsibility. Carter smiled. So, we’re going rogue. We’re exercising tactical discretion. That’s a new name for insubordination. Cork marshall me if you want, but help me first.

They formulated a plan. Company B would officially resume its advance, but at a slower pace, allowing time to organize transportation for the children. Morrison would request additional medical supplies from division, citing combat casualties rather than civilian refugees.

They would come vehicles from the village farm trucks, civilian automobiles, anything with wheels to transport those too weak to walk. The teachers would continue supervising the children, maintaining order, providing the continuity of care that had kept them alive this far.

By midm morning, they had assembled a convoy that looked like a refugee column from some earlier, more primitive war. Trucks loaded with children, soldiers walking alongside, teachers organizing singing games to keep spirits up during the journey. The village donated what supplies it could blankets, a few medical items, some food, partly out of genuine charity, and partly out of fear that the Americans would take more if they refused.

The advance continued south toward Munich through landscape that bore increasing evidence of war’s conclusion. White flags everywhere. Abandoned military equipment. Soldiers who surrendered before shots were fired. They passed through villages that had been bombed, houses where walls had collapsed, but photographs still hung on remaining fragments.

Family portraits watching the ruins of Germany’s ambitions. At each stop, Morrison requested additional supplies. At each checkpoint, he explained the situation to officers who had the authority to order him back into formation. Some threatened court marshal. Others looked at the children and found excuses to let him continue. A captain from Chicago requisitioned six field ambulances that were technically assigned elsewhere.

A major from Boston arranged for a field kitchen to accidentally deliver rations to the wrong coordinates. Small acts of rebellion. Individual officers choosing mercy over regulations. Private Williams, keeping records in his careful accountant’s handwriting, documented everything. for the court marshal,” he said with gallows humor. “You’re going to need good documentation.” But he smiled when he said it.

And at night, he taught German children how to play cards, penttoing rules when language failed, laughing at the universal humor of bad hands and worse bluffs. News traveled slowly in 1945, but it traveled. A journalist embedded with division headquarters heard about Morrison’s unauthorized refugee convoy and smelled the story.

He arrived with a camera, a notepad, and a skepticism born from covering three years of combat that had taught him to doubt official narratives. His name was Robert Chun, son of Chinese immigrants, a reporter for the Associated Press who had landed at Normandy with the first wave and survived by being too busy taking notes to think about dying.

He found Morrison in a village square supervising distribution of soup to 200 children while his men maintained perimeter security and pretended this was normal military operations. Lieutenant Morrison, I’m with the AP. I heard you’ve got quite a situation here. Morrison looked up from a little girl he was helping eat. Exhaustion making him too tired for subtrafuge. We found children in a barn.

We’re trying not to let them die. That’s the situation. Shawn pulled out his notepad. Mind if I ask some questions? What followed became one of the most widely published stories of the war’s final days? Chun interviewed Morrison, Carter, the teachers, even some of the children through translators. He photographed soldiers sharing chocolate with enemy children.

German teachers weeping with gratitude, a three-year-old girl asleep in the arms of an American sergeant who had three daughters back in Iowa. The story ran in newspapers across America under the headline, “Humanity among the ruins. American G is save 200 German children. It described the barn, the march, Morrison’s decision to disobey orders rather than abandon children. It quoted Greta Schneider.

They fed our children before they fed themselves. They carried our babies though they had every reason to hate us. This is what we were never told about Americans. The article reached Camp Hearn, Texas, where German prisoners of war worked on farms and read American newspapers in their barracks.

It reached New York, where Morrison’s parents wept with pride and terror. It reached the Pentagon, where generals debated whether to court marshall an officer who had violated orders to save enemy children. But mostly it reached American living rooms where families gathered around radios and read newspapers over breakfast, learning about their boys overseas, doing something that transcended military objectives.

In an era dominated by stories of destruction and death by photographs of cities reduced to rubble and casualty lists that grew longer every day. Here was something different. A story about saving instead of destroying, about mercy instead of revenge. Letters began arriving at division headquarters, thousands of them, from parents who had sons overseas.

From teachers who recognized Greta Schneider’s courage, from Americans who wanted to believe their country stood for something beyond just winning wars. One letter came from a woman in Oregon who wrote, “My son died at Normandy. If he could see what Lieutenant Morrison did, he would be proud. I am proud.

This is what we’re fighting for. Not just to defeat evil, but to prove we’re better than it. The convoy reached the outskirts of Munich in late April as the city prepared to surrender. The war was ending not with dramatic last stands, but with exhausted collapse like a boxer who had taken too many hits and could no longer raise his arms to defend himself.

White flags appeared on buildings. Soldiers abandoned weapons in the streets. Civilians emerged from basement where they had hidden for weeks, blinking in sunlight that revealed the ruins of what had been one of Germany’s most beautiful cities. Morrison established a temporary facility in a partially destroyed school building.

Military government units had finally caught up with the advance, bringing doctors, supplies, and bureaucrats who specialized in displaced persons. The children were registered, photographed, given medical examinations, and entered into databases that would attempt to reunite families torn apart by war.

Some parents were found. A mother from Cologne who had been searching for her two sons for 6 weeks. A father who had survived the war working in a factory and spent every day since searching refugee camps. These reunions were moments of joy so pure they seemed almost obscene against the backdrop of destruction families whole again. Children crying in their parents’ arms.

Proof that some things could be salvaged from the wreckage. But most had no one. Parents dead in bombing raids or lost somewhere in the chaos of Germany’s collapse or simply vanished into the fog of war that swallowed entire populations. These children became wards of military government, assigned to orphanages being established across occupied Germany.

Numbers and ledgers that tracked the cost of war in ways that casualty figures never captured. Greta Schneider stayed with the children, working with American authorities to ensure they received proper care. She had kept them alive for weeks through pure will, and she could not abandon them now just because the war was over. She worked 18-hour days translating, organizing, advocating for children who had no one else to speak for them.

Morrison found her one evening in the school courtyard, sitting on rubble that had once been a wall, looking at sunset that painted the ruins of Munich in shades of gold. “We did it,” he said, sitting beside her. “They’re safe.” “Safe?” Greta repeated, tasting the word. “What is safe? They are alive. Yes, they have food, shelter, doctors, but safe. She gestured at the destroyed city. Their homes are gone. Their parents are gone.

The world they knew is gone. We kept them alive to inherit ruins. Morrison had no response. She was right. They had saved the children from immediate death, but what came after remained uncertain. Germany would be occupied for years. divided, rebuilt by conquerors who would shape it according to their own visions.

These children would grow up in a world defined by defeat, by shame, by the long shadow of crimes committed in their nation’s name. But they will grow up, Greta said, reading his thoughts. Because of you, because American soldiers carried enemy children, though they had no obligation to do so. that matters maybe more than we understand now. 3 weeks later, Morrison received orders to return to division headquarters.

The war in Europe was officially over Germany and surrendered on May 8th, 1945. Celebrations had erupted across America. Soldiers danced in the streets of Paris and London. But in the ruins of Bavaria, the victory felt hollow, overshadowed by the magnitude of destruction.

At headquarters, Morrison was informed that charges had been filed against him for disobeying orders, delaying his unit’s advance and commandeering military resources for unauthorized purposes. A court marshal would be convened, and he would face potential dishonorable discharge and imprisonment. He sat in the waiting room outside the colonel’s office, exhausted beyond caring about consequences. If they court marshaled him, so be it.

He had saved 200 children. Whatever came next seemed trivial by comparison. The door opened. Lieutenant Morrison, the colonel will see you. Morrison entered, snapped to attention. Colonel Brennan sat behind a desk covered in paperwork. A man in his 50s, who had commanded men since the first war, who had seen enough combat to understand the difference between regulations and right action.

At ease, Lieutenant Brennan gestured to a chair. Sit down, Morrison sat, waiting. Brennan shuffled papers, reading reports that Morrison recognized, his own action reports, statements from soldiers in Company B, testimony from German teachers, copies of Chun’s newspaper article. Finally, the colonel looked up. You disobeyed direct orders.

Do you understand that? Yes, sir. You delayed your unit’s advance, disrupted regiment’s operational timeline, and commandeered military resources without authorization. Yes, sir. You also, Brennan continued, his voice shifting slightly, saved 200 children who would have died if you had followed protocol. You did something decent in a war that hasn’t had much decency.

and you embarrassed every bureaucrat who wanted to court marshall you because the press made you a hero and they look like villains. Morrison said nothing, unsure where this was leading, Brennan opened a folder, pulled out a single sheet of paper. This is a letter from General Eisenhower’s office. Apparently, he read Chun’s article.

A general specifically requested that no charges be filed against you. He wrote, and I quote, “In a war defined by destruction, we need more men like Lieutenant Morrison, who remember that winning means something beyond just defeating the enemy.” He slid the paper across the desk. Morrison read it, barely processing the words. “The charges are dropped.

” Rein said, “You’re officially reprimanded for insubordination, which goes in your file and means nothing. You’re also being recommended for accommodation, though that’s still working through channels. He paused, a slight smile crossing his face. Off the record, you did good, Lieutenant.

You did the right thing when the right thing was hard. That’s what officers are supposed to do, even when regulations say otherwise. Morrison felt something release in his chest. Tension he had been carrying for weeks. Thank you, sir. Don’t thank me. Thank the 200 kids who are alive because you gave a damn.

Brennan stood, offering his hand. War’s over in Europe. You’ll ship back to the States in a few months. Get discharged. Go back to being a teacher or whatever you were before. But remember this, what you did mattered. Not because it changed the outcome of the war, but because it changed the outcome for those kids. That’s worth more than any medal.

Morrison returned to Oregon in August 1945. Arriving home to a ticker tape parade he did not want an attention that made him uncomfortable. He tried to explain that he had just done what anyone would do, that his men deserved credit, that the German teachers were the real heroes for keeping children alive through weeks of displacement.

But America wanted heroes who saved children instead of just killing enemies. Chun’s article had been reprinted in hundreds of newspapers. Radio programs had dramatized the story. Hollywood had inquired about film rights. Morrison, who just wanted to return to his classroom and forget about war, found himself giving speeches, attending ceremonies, answering questions for reporters who wanted to know what he had felt when he found the children. He never found good answers.

The truth was too complex, too bound up with loss and anger and the grinding exhaustion of war. He had saved those children partly from compassion and partly from guilt guilt about his brother’s death, about the Germans he had killed, about the part he had played in a war that destroyed entire cities. Saving 200 children did not balance those scales.

But it was something, a moment of creation in a landscape of destruction. The German teachers were offered passage to America immigrants sponsored by churches and community groups that wanted to help. Greta Schneider accepted, arriving in New York in September 1945. She settled in a small town in Pennsylvania, taught German language at a local high school and spent her evenings writing letters to former students scattered across occupied Germany. She kept in contact with Morrison.

They exchanged letters for decades, birthday cards, and Christmas greetings, and occasional longer correspondence about how the children were fairing. Many had been adopted, finding new families in the ruins of the old. Others had been reunited with surviving relatives. A few had vanished into the chaos of postwar Europe, their fates unknown.

Hans, the 11-year-old translator, eventually immigrated to America in 1952. He became an engineer, married an American girl, raised four children, who never had to hide in barns or walk for weeks searching for safety. He named his first daughter Greta. Some of the children never recovered.

Years in orphanages, in foster homes, carrying trauma that shaped their entire lives. They became alcoholics or criminals or simply broken people who could not find their way in a world that had taken everything from them. The barn, the march, Morrison’s mercy. These things had saved their lives, but could not heal the damage that war had inflicted.

But others thrived. They became doctors, teachers, businessmen, artists. They built families, raised children, contributed to the Germany that rose from ruins. And when they told their children about the war, they spoke of American soldiers who had found them in a barn and chosen mercy over convenience, who had carried them to safety, though regulations said they should not.

In 1985, 40 years after the wars end, a reunion was organized. Someone no one remembered exactly who had the idea to gather the survivors, the children who had been saved, the soldiers who had saved them. Television coverage was arranged. German penned. American officials attended, making speeches about reconciliation and the enduring bonds between former enemies.

Morrison flew to Germany, now an old man of 64, retired from teaching, living quietly in Oregon with his wife and grandchildren. He had not thought about the barn in years, had trained himself not to think about it, because thinking about it meant thinking about the war, and he had spent decades trying to forget the war.

But he went to Germany because some of the children wanted to thank him, because Greta Schneider, now 85 and frail, had written asking him to come, because 40 years was enough time that maybe he could face it without the old grief overwhelming him. The reunion took place in Munich in a convention center built where the school had stood.

200 people attended the children who are now middle-aged adults, the soldiers who are now grandfathers, German and American mixed together, speaking in English and German, and the universal language of shared experience. Morrison found himself surrounded by strangers who embraced him, who cried on his shoulder, who introduced children and grandchildren and said, “This is the man who saved my life.

” A woman in her 40s, she had been 3 years old in the barn, gave him a photograph. It showed a little girl asleep in the arms of an American soldier. The photo was torn and faded, but the image was clear. “That’s me,” she said. “And that’s Sergeant Carter.

I carried this my whole life, reminding myself that mercy exists even in the darkest times. Hans found him, now a successful engineer with grown children, speaking English with only a slight accent. Lieutenant Morrison, I have wanted to thank you for 40 years. They embraced two old men who had once been a soldier and a child, connected by circumstances that defied easy categorization.

Not friends, not family, but something else. Survivors of the same trauma, participants in the same moment of grace. Greta Schneider gave a speech. She spoke about the barn, about the march, about American soldiers who had violated regulations because regulations conflicted with decency.

She spoke about letters she had received over the years from former students, about lives saved and families built and contributions made to a world that almost killed them. “We tell our children that war is evil,” she said, her voice carrying through the hall with the authority of a lifetime’s teaching. “And it is. But war also reveals what humans are capable of when pushed to extremes.

Sometimes that revelation is terrible cruelty beyond imagination, destruction without mercy. But sometimes it is beautiful soldiers carrying enemy babies. Men sharing their last rations with children who sang songs about their destruction. A lieutenant who risked court marshal because he could not abandon the crying he heard in a barn. She looked directly at Morrison. You saved us.

Not just our lives, though. That would be enough. You saved something more important. Our faith that humans could be good even when everything pushed them toward evil. That matters. 40 years later, 60 years later, 100 years later, it will still matter. The barn still stands. Or what remains of it. The roof has collapsed.

The walls lean at angles that defy gravity. and vegetation has reclaimed the interior where children once huddled in darkness waiting to die. A plaque was installed in 1995, marking the site as historically significant, explaining in German and English what happened there in April 1945.

Tourists visit occasionally, mostly Germans who want to understand their history. Americans tracing family members who served in the 45th Infantry Division. They stand in the meadow looking at ruins trying to imagine what it was like. The crying children. The American lieutenant making a choice that violated regulations but honored something more fundamental. The march south through a landscape of defeat and destruction. Soldiers and children mixed together.

Enemies transformed into protectors. Morrison died in 1998 at home in Oregon surrounded by family. His obituary mentioned his service in World War II, his decades teaching high school, his devotion to his wife of 53 years. It included a paragraph about the barn, the children, the decision that made him briefly famous.

His family donated his papers to the National World War II Museum, including letters from Greta Schneider, photographs from the reunion, and a small notebook where he had written decades earlier. Regulations exist to serve humanity, not replace it. We save the children because that’s what humans do when regulations fail. The children now grandparents themselves. Some greatgrandparents carry the memory forward.

They tell their descendants about the barn, about American soldiers who chose mercy when vengeance would have been easier. They show photographs, read letters, pass on stories that grow richer with each retelling. In schools across Germany and America, teachers use the story as a lesson about moral courage, about the choices individuals make when systems fail.

They show Chun’s photograph soldiers carrying children, German teachers weeping with relief, a little girl asleep in Sergeant Carter’s arms. They ask students, “What would you have done? Would you have followed orders or followed conscience?” Most students say they would have done what Morrison did.

But most students have never faced that choice, have never heard children crying in a barn while regulations demanded they march on. It is easy to choose mercy and theory, harder when careers and lives hang in the balance. But Morrison chose. And because he chose, 200 children lived. Because he chose, families were rebuilt. Because he chose, the world received a small measure of grace in a war that had very little grace to spare.

The barn collapsed further in 2010, finally surrendering to weather and time. But the plaque remains, and people still visit, still stand in the meadow, remembering what happened there. Some leave flowers, others just stand in silence, contemplating the strange alchemy that transformed enemies into family. They created bonds stronger than nationality or ideology.

War reveals humans at their worst and at their best, often simultaneously. It creates situations where a single decision can echo across generations, where a lieutenant says choice to disobey orders can save 200 lives and reshape how we understand mercy in the midst of destruction. Morrison never considered himself a hero. He insisted until his death that he had just done what anyone would do, that his men deserved credit, that the German teachers were the real heroes. But history remembers him differently.

History remembers the barn, the crying, the choice to violate regulations because regulations conflicted with something more fundamental than military efficiency. In the end, that is what we remember from wars. Not the battles won or territories secured, but the moments when individuals chose decency over convenience, mercy over revenge, humanity over regulations.

These moments do not change the outcome of wars. They change something more important. They change what wars mean, what we carry forward from devastation. 200 children, one barn, a lieutenant who heard crying and could not walk away. That is the story. That is what followed.

And 40 years later, 80 years later, as long as people remember, it still amazes.