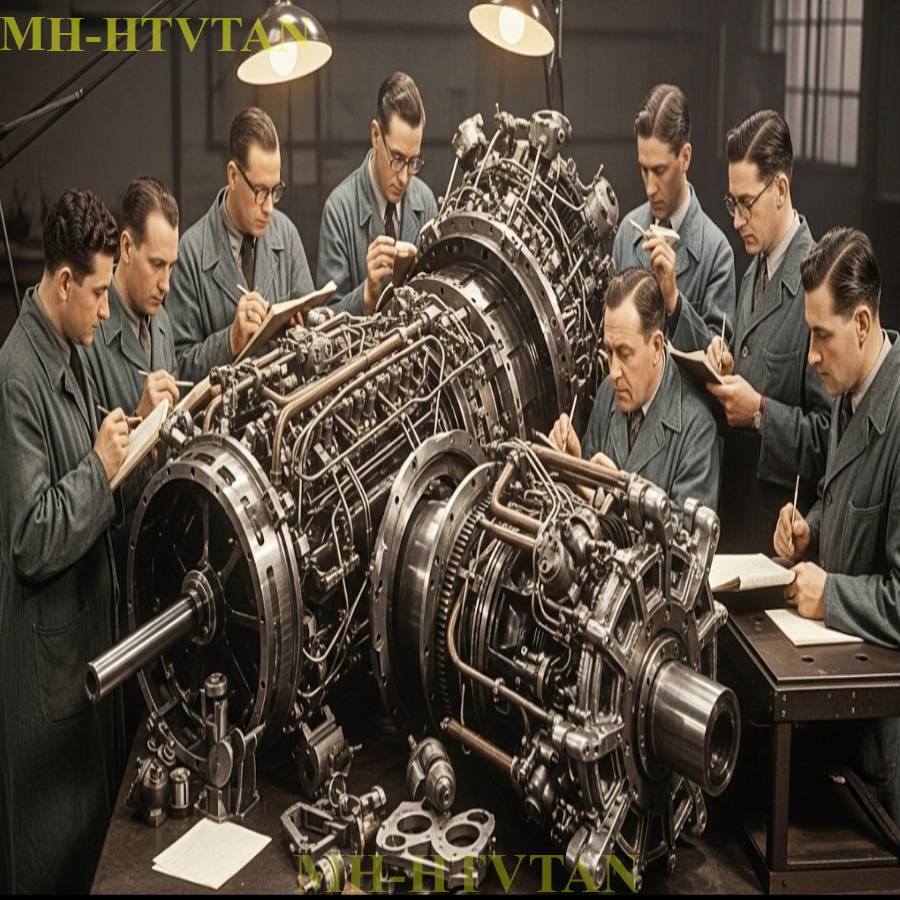

Berlin, late autumn 1940. Inside a narrow hanger at the Luftwafa’s technical office, a group of German engineers surrounded a wooden crate stamped with faded American markings. The air smelled of oil and cold metal. The crate had been seized in France, its contents, an American Liberty L12 aircraft engine, a relic from the previous war. As the crowbars split the crate open, the men burst into laughter.

This one of them sneered is what they call engineering. The Liberty engine looked crude compared to the precision machined Maybach HL 230 units powering German armor. Its cast iron cylinders bore rough edges. Its bolts seemed oversized and unevenly finished. The fuel lines were thick, almost agricultural. A tractor engine wearing a uniform, another joke rushing his hand across the dull metal.

For a moment the room was filled with the sound of superiority, the confident tone of men who believed they represented the pinnacle of mechanical civilization. They prided themselves on perfection, the tight tolerances of German pistons, the fine polish of crankshafts that glimmered under laboratory lights, the symphony of synchronized precision that defined every Maybach dameler or Junker’s product.

To these men, engineering was an art form. Every line on a blueprint carried the weight of cultural identity. They had grown up in workshops where tolerances were measured in microns, and errors meant disgrace. Across the table, a young technician lifted one of the Liberty’s pistons and frowned. Heavy, he muttered. And look at this connecting rod.

It’s forged, not machined. Primitive. Another engineer nodded. The Americans can’t even file a clean surface. Their philosophy must be if it fits it works. The laughter that followed was sharp and confident. They truly believed that such machines had no place in a modern war. The head of the examination team, Dr.

Hans Wulmer, a respected veteran of Daimler Benz, wrote in his notebook, material quality average. Design simplistic workmanship civilian level. To him, it was a short report. He expected the meeting to last an hour at most, enough to confirm that Germany had nothing to learn from American mass production.

Outside, the snow was beginning to fall over Berlin, muffling the distant hum of factories that produced engines measured in perfection not in numbers. But that night, as the technicians began to clean the Liberty surface for closer inspection, something unexpected caught Vulmer’s eye. The engine, though crude, showed remarkable consistency.

Every bolt head was identical. Every gasket matched perfectly. The spacing of components was not random. It was standardized. He measured the bore and stroke. The ratio was a perfect multiple of common metric tools. Yet the dimensions were expressed in inches. They’ve built it for machines, not for men, he whispered. The next morning, curiosity replaced arrogance.

They began disassembling the Liberty with methodical precision. Within hours, the pattern became undeniable. Interchangeable parts, repetitive geometry, threaded fittings designed to be replaced by anyone with a wrench. It was not the work of a master craftsman. It was the product of a philosophy that valued speed over beauty. Every part looks ugly, one technician muttered, but they fit without hand adjustment.

Wulmer ran his hand along the oil manifold, tracing its simple lines. Ugly, he agreed, but deliberate. For the first time, silence replaced laughter. Across the Atlantic, that same design philosophy had built an army. The Liberty Engine had not been conceived for museums, but for assembly lines. It was designed to be multiplied, not admired. The Germans didn’t know that yet.

To them, the Liberty was still a curiosity, an industrial fossil from a culture that misunderstood engineering. Yet even as they mocked it, they were touching the blueprint of America’s future, a system that turned imperfection into power. By evening, Dr. Wulmer’s notes began to shift in tone. He no longer wrote poor quality. Instead, he began marking efficient, uniform, reproducible.

He did not yet understand what those words would mean for Germany’s fate, but something inside him sensed the threat. The Liberty might not have been beautiful, but it was dangerous because it represented a different kind of genius, one that Germany had never needed to respect before. The men did not speak of it aloud, but the unease was spreading.

The laughter that had filled the hangar in the morning had vanished by nightfall, leaving only the ticking of cooling metal, and the quiet realization that perhaps behind the rough surfaces and crude castings, there was an intelligence they did not yet understand. If you’ve ever believed that true power comes only from perfection, type the number seven in the comments.

And if you disagree, if you think beauty belongs only to precision, then like this video, because this story is not about who built the prettiest machine, it’s about who built the one that could win a war. Detroit, Michigan, July 1917. The city shook with the rhythm of progress. Steam whistles, stamping, presses the clatter of steel on steel.

America had just entered the Great War, and Washington demanded an air force that did not yet exist. European powers had been building aircraft engines for years, refined, complex, meticulously handcrafted by engineers who treated every cylinder as a work of art. But the United States had nothing comparable.

What it did have was something far more powerful than craftsmanship, an industrial system capable of scaling any idea into infinity. When the army’s aviation section sent out its urgent telegram, an aircraft engine suitable for war use must be designed immediately. Two names surfaced. Jesse Vincent of Packard Motor Company and Elbert Hall of Hall. The challenge was insane.

They were asked to design a high-performance 12cylinder engine within 60 days. something that could match the best German and British designs, but could also be built by the tens of thousands. Vincent’s response was simple. We’ll make an engine that anyone can build.

The pair gathered a small team in a rented office above Packard’s test department. They tore through European blueprints comparing the Mercedes D3 and the Rolls-Royce Eagle and then did something heretical. By European standards, they simplified everything. No exotic alloys, no hand fitted bearings, no delicate tolerances that required master machinists.

The new engine would use standardized parts, interchangeable components, and simple geometry that could be mass- prodduced on ordinary lathes. It would run on mediocre fuel. It would start in the cold. It would be built not by engineers, but by factory workers. They called it the Liberty L12. 12 cylinders in a 45 degree V configuration each with a bore of 5 in and a stroke of seven displacing nearly 27 LERs.

It produced 400 horsepower at 1800 revolutions per minute numbers that stunned even its creators. But what made it revolutionary was not its power. It was the fact that every single dimension was designed for repeatability. A mechanic in Detroit could assemble it exactly the same way as one in Dayton or Long Island. Vincent’s guiding rule was brutally practical.

If it can’t be made fast, it won’t be made at all. Threads were standardized to existing automotive sizes. The connecting rods were forged rather than machined cutting production time by 70%. The crank case used straight cuts instead of curves, easier for milling machines to reproduce. Even the cam shaft timing gears were positioned so that unskilled workers could align them by eye.

Nothing about it was elegant, and that was the point. Within 43 days, the first prototype ran on a dynamometer. Newspapers called it the fastest birth in industrial history. Within 63 days, Liberty engines were roaring on the test stands of Packard and Ford.

And when the army inspected the design, they saw more than a machine. and they saw a manufacturing system in blueprint form. The War Department ordered 22000 units before the first one had even been delivered. Factories across the nation retoled overnight. Packard, Lincoln, Buick, and Ford shared identical jigs and gauges. Every drawing used the same reference standards.

For the first time, American industry was unified by measurement itself. Men and women who had never seen an aircraft built engines by the thousands because they didn’t need to understand every bolt. They just needed to follow the pattern. In less than a year, 2478 Liberty engines were produced. Compare that with Germany’s process.

At the same time, the Mercedes D3 took master craftsmen months to assemble. Only a few hundred could be made each year. The Liberty’s parts could be stamped, forged, and assembled by anyone trained for a week. A mechanic from Kansas could install a cylinder block built in Ohio, attach pistons from Illinois, and fit a carburetor from California, and it would all work perfectly.

The Germans called this mechanical barbarism. The Americans called it progress. By late 1918, Liberty engines powered the DH4 bomber, the Handley Page 0400s. the De Havland night reconnaissance planes and dozens of experimental tanks and boats. For the first time, the US military had a single universal power plant that could fit air, land, and sea platforms.

It was not beautiful. It leaked oil. It rattled. But it ran always. The engine became a symbol of a new kind of warfare, industrial warfare. The Liberty’s real achievement was not that it flew. It taught machines how to make machines. Every production line, every gauge, every training manual born from the Liberty program became the foundation of American mass production through the 1920s and 1930s.

When Henry Ford later said, “The real miracle is not what we build, but how fast we can build it.” He was speaking in the shadow of the Liberty engine. Decades later, when those same German engineers in Berlin dismantled their captured liberty, they were looking at a time capsule, a design created before they ever imagined mechanized war on such a scale. They saw a philosophy in metal form.

Build it once, build it everywhere, build it forever. If you believe that genius isn’t about perfection, but about scalability, type the number seven in the comments. If you think art still belongs above efficiency, then presslike instead. Because in 1917, America didn’t just design an engine.

It designed a way of thinking that would change how wars and worlds were built. Berlin, early winter 1940. The captured Liberty engine lay on a steel workbench beneath a canopy of cold light. Frost glazed the windows of the Luftvafa technical office, and the air smelled of kerosene and solder. The morning began with confidence, another routine examination of foreign scrap, another chance to confirm the superiority of German craftsmanship.

But as the hours passed and each layer of metal peeled away, the room grew quieter. Dr. Hans Wulmer stood at the head of the table clipboard in hand, while his assistants loosened the cylinder heads with socket wrenches. Careful, he muttered, not out of reverence, but curiosity. As the bolts came free, they noted something strange. Every bolt was the same size, every washer identical.

The pattern was deliberate. One assistant measured the thread pitch, expecting irregularities. Instead, he found uniformity so consistent that it could only mean one thing. These parts had been mass- prodduced with the same tooling. They designed it to be built by numbers, he whispered. The head mechanic, a veteran of the Maybach plant, examined the pistons.

Forged, not machined, he said with mild contempt. Crude, but strong. He checked the weight of each piston and blinked. They were all identical to within a fraction of a gram. Impossible, he said quietly. Not with this many pieces. Wulmer leaned closer, his eyes narrowing behind wire rim glasses. Impossible, he repeated, but not with arrogance, with wonder.

They removed the oil pump next. It was oversized and rough, its gears cut in wide tolerances. One technician scoffed, “They must lose pressure at every revolution. Yet, when they examined the oil passages, they discovered something unexpected. The clearances were deliberate, wide enough to prevent clogging from dirty fuel simple enough to be machined by the thousands.

The pump could fail halfway and still feed enough oil to keep the engine running. It was an act of brutal pragmatism. Do you see? Wulmer set his voice low. It’s not built to last forever. It’s built to survive neglect. He ordered the carburetor disassembled. Inside the jets were simple brass cones. No polishing, no delicate adjustments. Each component could be swapped with another without recalibration.

The Americans don’t tune engines. An assistant muttered. They manufacture them like rifles. On a nearby table, another engineer traced the shape of the intake manifold. It’s asymmetrical, he said. Unbalanced flow yet. The performance data shows stability. Wulmer nodded. They sacrificed elegance for production speed. The air doesn’t flow perfectly, but it flows fast enough.

By noon, the engine was a pile of parts pistons in neat rows. Crankcase halves opened like a metal anatomy lesson valves and gears arranged across the floor. It looked like a crime scene of industrial logic. The Germans circled in silence taking notes. They realized that the Liberty had been designed with one goal to minimize decision-making on the factory floor. There was no room for interpretation, no requirement for genius.

Any worker anywhere could build it with the same result. Wulmer dictated his observations while a stenographer typed beside him. Material moderate grade steel cast iron cylinders finish rough but consistent assembly modular with standardized bolts throughout. Design intent simplification for mass manufacturer. He paused then added a line that would haunt him for years.

This engine is the product of a civilization that values quantity as quality. Late in the afternoon, they reassembled part of the crankshaft to test balance. Even without fine adjustments, it rotated smoothly. The Germans exchanged uneasy glances. In their world, such precision required hours of manual fitting.

Here, it appeared effortlessly baked into the process. The American designers had engineered tolerances into the system itself, trusting repetition over artisanship. They’ve removed the craftsman from the equation, Wulmer said softly. They’ve made perfection unnecessary. A young engineer named Friedrich Keller studied the cooling system.

These fins, he said, running his hand along the block aren’t optimized for air flow. They’re just adequate. He sounded almost offended, but when he measured the heat distribution, the results were astonishingly even. Adequate, it turned out, was more than enough.

As dusk settled, they mounted the disassembled Liberty on a stand and connected a test crank motor. The ignition system was archaic magneto sparks instead of electronic precision, but it fired immediately. The engine coughed, spat black smoke, and settled into a deep rhythmic growl. The noise was coarse, mechanical, unrefined, but steady. It shook the workshop with a primitive energy that felt less like machinery and more like instinct.

One of the engineers covered his ears. It sounds like a tractor, he complained. Wulmer didn’t respond. He watched the gauges instead. Stable oil pressure, even temperature, consistent timing. The engine refused to die. They let it run for 40 minutes. It didn’t overheat. It didn’t falter. It simply roared defiant and alive.

When they finally shut it down, the air was thick with the smell of exhaust and humility. That night, Wulmer sat at his desk reviewing his notes. The phrases that once filled his reports, primitive, inelegant, unsuitable, had been replaced by new words, robust, reliable, standardized. He realized that this engine, this artifact of another era, represented something he had dismissed his entire career, the genius of the ordinary.

The Liberty did not need perfection. It needed to exist by the thousands. In his final line that evening, he wrote, “We have built machines to honor our engineers. They have built engines to honor their soldiers.” He underlined it twice. If you believe that the real genius of war lies not in invention, but in replication, type the number seven in the comments.

If you think craftsmanship still outweighs production press like because when those German engineers took apart the Liberty, they weren’t just studying an engine. They were dismantling the myth of their own superiority. Detroit, 1918. The war in Europe was devouring machines faster than any factory could build them. France was begging for engines. Britain was exhausted. But in America, something unprecedented was taking shape. A temple of production that would never sleep.

At the corner of Wyoming Avenue and Fordson Road, just west of the River Rouge, the Ford Liberty engine plant stretched into the horizon like an industrial cathedral. It was a mile long, lined with glass skylights echoing with the rhythmic pulse of machines. 5,000 men and women worked in three shifts 24 hours a day.

Their world was noise rivets, hammering pistons, slamming steel, groaning under hydraulic presses. The Liberty engine had been designed for them. No special tools, no custom craftsmanship, just precision through repetition. Every worker knew a single task by heart. One drilled bolt, one gasket line, one torque measurement, and then passed the part down the line.

The result was a miracle of synchronization. Every 30 minutes, another 12cylinder heart rolled off the assembly line, destined for a tank, a bomber, or a boat. Henry Ford himself visited often, walking the floor with his hands behind his back, watching the choreography of motion. He didn’t speak much.

He didn’t have to. The factory spoke for him. Cranes glided over rows of Liberty engines, each identical each, numbered, each, ready for war. The philosophy was simple. remove thinking from the process. The machines would think instead. By February 1918, Packard, Lincoln, Buick, and Ford were all producing Liberty engines from identical blueprints.

Each company used the same jigs, the same gauges, the same measurement standards. It was the first time in history that rival manufacturers shared not competition, but synchronization. A connecting rod made in Detroit fit perfectly into a crank case from Philadelphia. An oil pump cast in Cleveland could bolt flawlessly onto a block forged in Chicago. The Liberty was no longer just an engine.

It was a language of manufacturing spoken across a continent. Women joined the lines in growing numbers. They assembled pistons, riveted engine mounts, and inspected cylinder heads under harsh white light. Many had never touched a machine before the war. Now they were building engines that would power entire divisions. “We don’t make parts,” one worker told a reporter.

“We make history one wrench at a time.” Outside the plant rail, cars lined up day and night. Each flatbed carried 10 completed engines wrapped in oiled canvas bound for ports in New York and Norfolk. The trains left every 6 hours, their whistles echoing through the Michigan cold. To Europe’s engineers, the numbers seemed impossible to Ford’s workers. It was just another Tuesday.

By the end of the war, 2478 Liberty engines had been built. Never before had such power been produced in such numbers. The cost per unit fell by 40% after just 6 months. Failures in testing dropped by half. The Liberty became not just a weapon of war, but a proof of concept that America’s real strength was not ingenuity, but multiplication. Across the Atlantic, the Germans were still building engines by hand. The Maybach HL 230.

The pride of their engineering was assembled by master machinists who could craft a piston to perfection, but could build only a few dozen a month. Each one took over 1400 man-h hours. In Detroit, a Liberty engine took less than 100. The numbers told a brutal story. Where Germany built one engine, America built 20.

Where the Luftwaffa relied on artisans, America relied on foremen and floor workers. Where Europe designed machines to last forever, America designed them to be replaced tomorrow. In 1919, an internal Ford memo summarized the philosophy that had driven the Liberty’s success perfection waste time. Time wins wars. That same line would be quoted two decades later when another American factory Willow Run would produce one B-24 bomber every 55 minutes. The Liberty had written the first chapter in that book.

For engineers like Jesse Vincent, the Liberty was never about beauty. If you looked for grace, he said later, you missed the point. We weren’t building sculpture. We were building survival. His words echoed through the decades. From the roar of P47 Thunderbolts to the rumble of Sherman tanks.

The DNA of the Liberty engine simplicity, repeatability, and standardization ran through all of them. Inside the Ford plant quality inspectors recorded statistics that bordered on the unbelievable. 96% of all Liberty engines passed final testing without major defect. The remaining 4% were repaired onsite, often within a day. Engines left the plant with serial plates reading built for liberty, built to last.

They weren’t exaggerating. Many continued running into the 1930s powering boats, trucks, even race cars. The real revolution, however, wasn’t mechanical. It was philosophical. Before the Liberty engineers were artists after it, they were system architects. Production lines replaced workshops. Blueprints replaced intuition. Measurement replaced pride.

The Liberty engine had proved that genius could be industrialized. By the time the Great War ended, American industry had changed forever. The same factories that once built cars, could now build aircraft tanks, and anything in between. The United States had learned that the true weapon of war wasn’t the machine itself. It was the capacity to build more of it.

When the Germans captured a Liberty 20 years later, they weren’t just examining an antique. They were holding the seed of their own defeat. The philosophy behind that clumsy old engine had evolved into something unstoppable production lines that could outbuild any enemy on Earth. In his Berlin notebook, Dr. Hans Wulmer would later write, “We built machines that required men. They built machines that replaced them.

” He wasn’t mocking anymore. He was describing the truth. If you believe that the real miracle of the 20th century wasn’t invention, but production, type the number seven in the comments. And if you think the world still belongs to those who can build faster than anyone else, then subscribe.

Because the story of the Liberty engine doesn’t end in 1918. It begins there in the milelong factory that never slept. Berlin, January 1941. The sky above the Templehoff hangers was the color of gunmetal, the kind of winter gray that swallowed sound. Inside the Luftvafa technical office, the Liberty engine sat fully assembled once more, gleaming dully beneath fluorescent lamps.

Its aluminum skin bore scratches from countless inspections, its bolts slightly worn from repetition. Around it stood 12 engineers, all veterans of Germany’s most advanced mechanical projects. The laughter that had once filled this room months earlier was gone. Dr. Hans Vulmer ran a hand over the cold casing, tracing the stamped words, “Packard Motorco Detroit.

” He whispered them slowly, almost reverently, as if they belong to another civilization. “Ready ignition,” he said at last. A mechanic connected the fuel lines, checked the magneto switch, and gave a silent nod. Wulmer turned the key. The Liberty coughed once, then erupted into a deep throaty roar that rolled through the hanger like thunder.

The sound was brutal, nothing like the refined hum of a Dameler Benz DB 6001 or or the tuned precision of a Junker’s Jumo. This was raw, uneven, almost primitive. But as the minutes passed, the Liberty kept running. Its exhaust turned from black to gray, its vibration smoothed into rhythm, and its gauges stayed steady. Oil pressure constant, temperature stable.

Every needle pointed where it should. Wulmer leaned close to the control panel and whispered, “It’s alive.” They increased the throttle. The Liberty howled, shaking the floor, blowing sheets of frost from the windows. 2100 revolutions, someone shouted. The engine didn’t falter. Another 10 minutes passed, then 20. Still steady.

The noise was deafening, but beneath it lay something eerie consistency. Even as the heat rose, and the air thickened with fumes, the Liberty refused to quit. One of the younger engineers, Keller, shouted over the roar, “It shouldn’t be this smooth. The tolerances are too wide.” Vulmer raised an eyebrow. and yet it runs better than ours when misaligned. Keller hesitated, staring at the spinning crankshaft.

How Volulmer didn’t answer. He knew how. The Americans had designed the Liberty to survive error, to endure imperfection. It was an engine that forgave its makers. When they finally shut it down after 45 minutes, the hanger filled with a ringing silence that felt heavier than the noise itself. The smell of oil lingered in the air, warm and metallic.

A mechanic wiped his hands on a rag, shaking his head. “Hair, doctor,” he said quietly. “This engine is 20 years old.” Wulmer nodded. “And yet it works as if built yesterday.” He walked slowly around the test stand, eyes tracing every line of the engine. “Do you know what this means?” he asked. No one answered. “It means we’ve been fighting the wrong war.” He gestured toward the engine. We design for excellence.

They design for endurance. We demand precision from every man. They demand simplicity from the design itself. When we fail, it’s because a craftsman makes an error. When they fail, it’s because the machine finally gives up. That is the difference between pride and power. Keller frowned.

But such crude methods, it feels unworthy of engineers. WMER looked at him for a long moment, his expression unreadable. unworthy,” he said quietly. “Tell that away of the thousands of these engines that powered their planes, their tanks, their ships all at once. Tell that to the factories that can replace what they lose before the day ends.

” He paused, lowering his voice. “They have built victory,” Keller, we have built pride. For a long time, no one spoke. The men stared at the Liberty, still warm, a faint trace of steam rising from its manifold. It looked almost alive, breathing in oil and exhaling heat steady and tireless. Wulmer scribbled in his notebook his handwriting uneven from fatigue. Engine runs beyond predicted tolerance.

Maintenance minimal. Simplicity equals reliability. No evidence of precision failure. He underlined the final sentence three times. Outside snow began to fall over Berlin again. The sound of distant anti-aircraft drills echoed from the city outskirts.

The war had not yet turned against Germany, but the first cracks were visible to those who looked closely enough. Wulmer looked down at the Liberty and felt something he had not expected envy, not for its performance, but for the philosophy it represented. They build as if time itself were a weapon, he murmured. Later that night, he sat alone in his office, the Liberty steady rhythm still echoing in his ears.

He thought of the endless reports from American factories, the statistics, the speed, the numbers that once seemed impossible. He remembered his own youth drawing blueprints for engines that took years to perfect machines that could only be built by the most skilled hands in Europe. And now he realized skill was no longer the ultimate currency. Scale was.

He closed his eyes and imagined an army of factories stretching beyond the horizon, each one building engines like this by the thousands. He could almost hear the rhythm of their pistons merging into one colossal heartbeat. That he thought was the sound of a nation that could not be stopped.

Before leaving, he tore a sheet from his notebook and wrote one final line. Perfection is fragile. Simplicity survives. He placed it inside a folder labeled captured Allied engines Liberty L12 and locked it in his drawer. If you believe that real power lies in the ability to endure rather than the desire to impress, type the number seven in the comments.

And if you think perfection without resilience is nothing but vanity presslike. Because on that cold January night, deep inside a Berlin hanger, a room full of German engineers finally understood that beauty had lost and endurance had won. The Liberty engine was not just an artifact of the past. It was a prophecy cast in steel. What those German engineers discovered on their workbench in 1941 was more than a machine.

It was a doctrine, a blueprint for how America would fight and win an industrial war. Every valve, every bolt, every crude casting was a line in a philosophy that valued endurance over elegance and multiplication over mastery. The Liberty had been designed to prove a single truth, a nation that could build faster than its enemies could think would always prevail.

Across the ocean, that philosophy had already evolved into a weapon of terrifying efficiency. By 1943, Detroit’s factories were producing tanks, bombers, and engines in quantities that defied imagination. The Liberty’s descendants were everywhere. The right R2,600 in the B-25, Mitchell, the Pratt, and Whitney R2000, 800 in the P47 Thunderbolt. The Ford GAAA V8 in the Sherman tank.

Each of these engines carried the same genetic code, standardized, overbuilt, and simple enough to be repaired in a muddy field by a 19-year-old mechanic. German intelligence reports from 1943 struggled to comprehend it. The Americans, one analyst wrote, manufacture engines as if they were bullets.

They do not value the machine. They value the production of it. The phrase would later be quoted in Allied propaganda films, but it had begun as an expression of disbelief. To European engineers, the Liberty’s philosophy was madness, a rejection of art and precision. To the Americans, it was liberation.

The irony was that the Liberty engine strength lay not in being perfect, but in being good enough everywhere. It didn’t need to be finely tuned to run in North Africa or the Pacific or the frozen tundra of Alaska. It didn’t demand elite fuel or expert maintenance. Its clearances were wide enough to forgive sand and cold its valves robust enough to survive overheating its timing, simple enough to be reset with basic tools.

The same design that the Germans had mocked as agricultural became the foundation for global mobility. By the middle of World War II, that idea had matured into an entire ecosystem. American factories no longer built individual engines. They built families of engines that shared the same components, the same threads, the same layout.

A worker trained on one could assemble any of them. Logistics officers didn’t need bespoke parts. They needed quantity. And quantity became strategy. When the first waves of Sherman tanks rolled across Europe, their engines came from automobile plants that had been converted in months, not years. When the B17s and B24s filled the skies, they burned fuel pumped by refineries synchronized with engine production schedules written in Detroit. It was the Liberty philosophy made real.

The battlefield begins at the factory. Germany’s factories by contrast remained temples of craftsmanship. Each Maybach, each Dameler Benz engine required trained hands, precise tools, and time. When those factories were bombed, the loss could not be replaced. America, however, could lose a 100 plants and still meet its quotas. Its strength was not in any one engine.

It was in the ability to build the next one. The engineers who had examined the Liberty eventually realized this truth too late. They had been proud of their artistry, their precision, their ability to make every machine unique. But uniqueness is a weakness in war.

Wulmer wrote in his postwar notes, “We mistook excellence for advantage. The Americans mistook simplicity for weakness. We were both wrong. What the Liberty represented was not the death of craftsmanship, but its evolution. It was engineering stripped of ego, industrialized humility, the understanding that the best design is not the one that dazzles, but the one that endures. And that was America’s secret. It wasn’t intelligence. It wasn’t resources.

It was faith in systems, in people, in the idea that a nation could build its way out of defeat. From the Liberty’s crude pistons to the B29’s pressurized cockpit, the same principle guided everything. Reliability is the highest form of genius. By 1945, when the war ended, the Liberty’s descendants had powered half the Allied victory. But the real legacy wasn’t the metal. It was the mindset.

Even as Germany’s factories lay in ruins, American production lines were still running, still making still, proving that the simplest machine can outlast the most beautiful one. If you believe that history favors those who build for endurance, type the number seven in the comments.

And if you think the true revolution of the 20th century wasn’t technological, but industrial, then like this video. Because the liberty’s secret wasn’t horsepower. It was the realization that the power to build again and again is the ultimate weapon. Berlin spring of 1946. The war was over. And so was the world that had once believed perfection could win it.

The Luftvafa technical office was a shell of cracked concrete and twisted steel. Through its shattered windows, weeds grew where engines once roared. Among the ruins, an old man moved slowly, his left hand trembling as he carried a small folder marked with fading ink. Captured Allied engines, Liberty L12. His name was Dr. Hans Wulmer.

He walked past the wreckage of his old laboratory, where the Liberty engine had once stood, like an intruder from another world. Now only the rusted stand remained, its bolts empty, its floor still stained with a ghost of burned oil. He knelt beside it, brushing away dust. The air smelled of damp concrete and the faint memory of fuel. He opened the folder carefully, the paper brittle and yellowed with time.

Inside were his notes written in the precise hand of a man who once believed numbers could explain everything. Material moderate grade B steel finish rough but consistent design intent simplification for mass manufacturer. He read the words aloud and almost smiled. He remembered the laughter of that first day in 1940, the arrogance, the jokes, the certainty that German engineering ruled the world.

He could still hear his own voice mocking the crude American design, calling it a farmer’s engine in a soldier’s body. And then he remembered the moment when the Liberty had come alive, when its roar had drowned their pride. That sound had haunted him ever since. Wulmer turned the page and found a single line underlined three times.

We have built machines to honor our engineers. They have built engines to honor their soldiers. He stared at it for a long time. The words no longer felt like analysis. They felt like confession. He reached into his coat pocket and took out a small metal fragment. The corner of a Liberty identification plate scorched and bent.

He had kept it through the bombing through the collapse of the Reich, through the years of hunger and silence. For him it was not a trophy. It was a reminder. The Liberty engine had not been perfect. It had leaked, rattled, and looked unfinished. But it had run and kept running long after the factories that mocked it had turned to ash. Outside, American trucks rumbled through the ruined streets, carrying crates of food and machinery.

The conquerors were rebuilding what they had destroyed, not out of cruelty, but out of capacity. Wulmer watched them pass their engines, steady and unremarkable, and he felt a strange mix of admiration and sorrow. The sound of those engines was the same rhythm he had heard years ago on the test stand, the heartbeat of a philosophy that had outlived his own. He began writing on a fresh sheet of paper.

His hand shook, but the words came easily now. The Liberty engine was not our enemy. It was our mirror. It showed us what we refuse to see, that perfection belongs to peace, not to war. We built masterpieces that died young. They built machines that refused to die. He paused, letting the ink dry. The silence in the room was absolute.

For a moment, he imagined the Liberty running again, its deep growl echoing through the hangar, steady and defiant. In that sound, he could hear the truth. America had not won by making better engines. It had won by making engines that anyone could build anywhere forever. He wrote one final paragraph slowly and deliberately.

If war has a lesson for engineers, it is this complexity is vanity. Strength lies in what endures not in what impresses. The Americans understood that first. We learned it last. He placed the page on top of the old reports, closed the folder, and sealed it with a strip of worn tape. On the cover, he added one more line in trembling handwriting. Perfection is fragile. Simplicity survives.

When he stood to leave, he looked around the room one last time. The sunlight caught the dust in the air, turning it golden. He whispered into the emptiness. They built engines to win wars. We built ours to win admiration. His voice broke slightly, and the world does not remember the admired. It remembers the victorious. He walked to the doorway, paused, and looked back once more.

The Liberty Stand stood like a gravestone. For a moment, he bowed his head, not to an enemy, but to an idea. Then he turned and disappeared into the fading light of postwar Berlin. As the narrator’s voice returns, the screen would fade to black. In 1917, the Liberty Engine was born in haste. In 1945, it was vindicated in fire.

It began as an experiment in mass production. It ended as a lesson for every engineer who ever believed perfection could conquer time. The faint echo of an engine starts up again rough, uneven, alive. The Liberty was never built to be beautiful. It was built to never stop.

If you believe that true greatness is not found in perfection, but in persistence, type the number seven in the comments. And if you want to keep hearing the forgotten stories of machines that changed history, subscribe to this channel because sometimes the loudest victories in war are whispered by engines that refuse to I