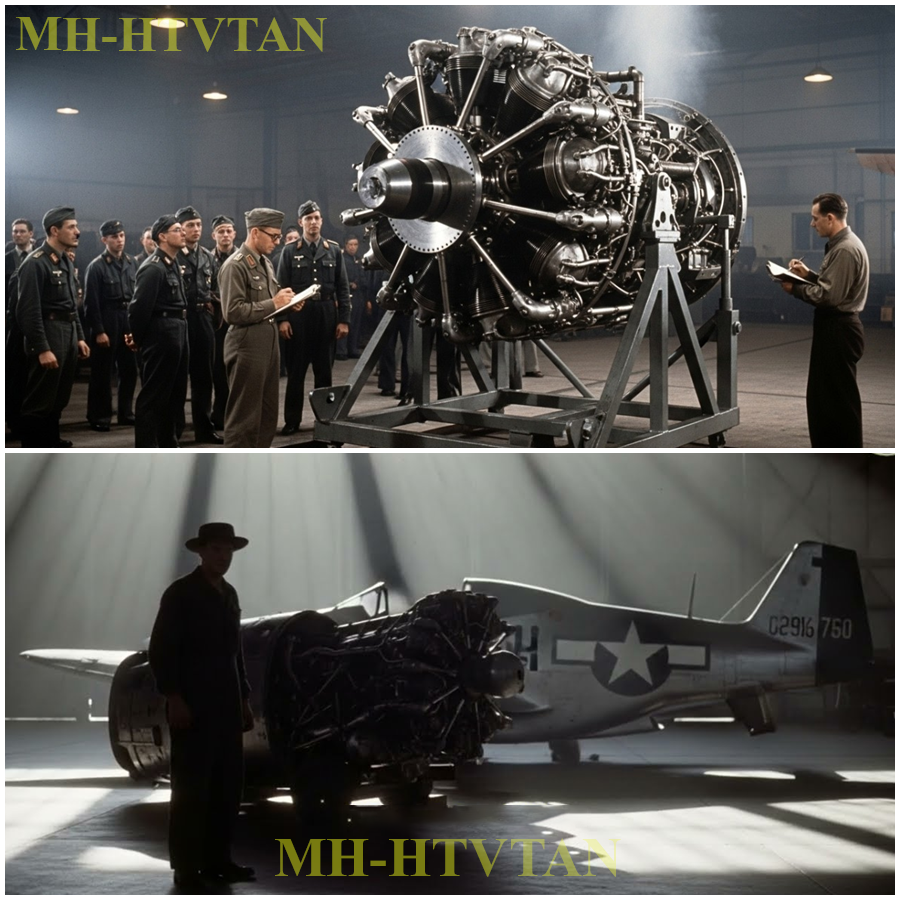

Summer 1944. Inside a hanger at Reklin, the Luftwaffa’s secret test center north of Berlin, a captured American fighter sat surrounded by men in gray coats. Its olive green skin was scarred by flack, but still gleamed under the overhead lights. Mechanics moved cautiously around the aircraft as if approaching a sleeping predator.

The letters stencled beneath the cockpit canopy read, “P51B Mustang.” Hans Fay, a senior test engineer with Dameler Benz, stepped onto the maintenance platform and ran his hand along the engine cowling. The metal was still warm. The fighter had been shot down only days earlier and delivered to Reclan nearly intact. Technicians had already drained the fuel, checked the oil lines, and confirmed the engine could still turn over. Fay motioned to start the test.

The propeller jerked, the starter winded, and a thunderous mechanical roar filled the hangar. The Merlin engine coughed, then settled into a deep, steady rhythm unlike anything the Germans had ever heard. The pitch rose to a shrill mechanical scream as the throttle opened a rising note that made tools rattle across the floor.

The sound was smooth, constant, and terrifyingly alive. Fay leaned close to the spinning blur of the propeller and said quietly, “St at we jet. It breathes like a jet.” Every man in the hanger stared at the tachometer as the needle climbed past the point where German engines usually began to choke. The Packard built Rolls-Royce Merlin 51650 kept accelerating perfectly balanced with no misfire, no drop in tone.

The gauges stayed in the green even as the air temperature rose. The sound was not the throaty growl of a piston engine fighting for air, but a clean rising whistle as if the aircraft itself were inhaling the atmosphere.

To the German engineers accustomed to the mechanical clatter of the Dameler Benz DB 605, it seemed unreal, almost supernatural. When the engine finally shut down, the hangar fell silent, except for the ticking of cooling metal. The engineers exchanged glances. They had seen captured Spitfires before even flown them. But this machine was different. It looked ordinary, yet the power they had just witnessed broke every expectation of what a piston engine could do at altitude. Fay opened his notebook and wrote a single line.

Begin full disassembly tomorrow. That night, over the hum of generators and the distant sound of air raid sirens, the technicians began removing the cowling panels. They worked methodically, photographing every part, tagging each bolt and bracket. The Merlin engine revealed a maze of pipes, ducts, and pressure lines that seemed to have no logical pattern.

Yet when they traced the airflow, they discovered a system designed not for elegance, but for endurance. It fed air to the engine in stages, cooling and compressing it, as if the machine were breathing in two separate lungs. It was in every sense an engine that shouldn’t exist, too powerful for its size, too light for its output, too reliable for its complexity.

In a report filed the next morning, FA wrote, “This engine maintained sea level power at over 9,000 m. Impossible.” But the data was there. Even on a static stand, the P-51’s heart behaved like something beyond the reach of conventional mechanics. The Germans, who prided themselves on precision, could not understand how such results came from what appeared to be rough American manufacturing. Every seam was riveted, not welded.

The finish was industrial, almost crude. Yet, it worked with a smoothness that mocked their obsession with perfection. Narration tone rises here. For years, the Luftwaffa believed its engineers understood every secret of piston propulsion. They measured efficiency by microns, calibrated tolerances by hand.

And then came this, an engine that rewrote the limits of altitude, endurance, and simplicity. The camera would linger on the drained Merlin block light glinting off the curved compressor housing. The voice would lower. What they found inside that engine would shatter the myth of German mechanical supremacy.

Before moving to part two, the narration closes with a direct challenge to the audience. Do you believe technology wins wars or is it still the human hand that decides victory? Comment number one if you believe innovation decides the outcome. Like this video if you believe courage matters more than machines. Because for the engineers of Reclan that question was no longer theoretical.

It was screaming in their ears from inside an American engine that breathed like a jet. In the years leading up to 1944, German engineers believed they had perfected the internal combustion engine. The Luftwaffa’s fighter squadrons flew on the backs of the Dameler Benz DB 601 and DB 605 mechanical masterpieces that seemed to embody the nation’s obsession with precision.

Each cylinder, each cam shaft, each fuel injector was built to the tolerance of a human hair. Pilots trusted them like heartbeats. And why shouldn’t they? These engines had carried mem across Poland, France, and the Soviet Union. They had outclimbed the hurricanes, outrun the Spitfires, and terrified the skies for five long years.

Inside the design offices of Stoutgart and Agsburg, there was an unspoken conviction German engineering could not be surpassed, only imitated. The DB 605’s direct fuel injection system was a marvel of craftsmanship. Its engineers could explain every pressure gradient, every degree of thermal expansion. Their work was the work of watch makers turned warriors.

To them, the idea that an American factory manned by unskilled laborers and production lines running day and night could produce a better engine was not just absurd, it was insulting. The arrogance was understandable. In 1941, the Luftvafa’s Messmid BF 109 climbed faster than anything the Allies had in the air.

The Jumo 211 that powered the J87 Stooka could run on contaminated fuel that would destroy most Allied engines. At low and medium altitudes, German engines were kings. Their precision paid off in responsiveness and efficiency. But hidden beneath that mastery was a flaw of philosophy. They were designed for perfection, not adaptation. The DB 605 delivered H475 horsepower at 18,000 ft.

Above $25,000, its power began to fade, strangled by thin air. The engineers knew it, and they accepted it. Combat was meant to happen below those heights, in the realm where their mechanical excellence dominated. But by 1943, the war had changed. American bombers were coming higher, heavier, and farther than anyone thought possible.

The B17s and B24s cruised above 27,000 ft wrapped in formations that blotted out the sun. German pilots could climb to meet them, but they couldn’t stay there. The engines gasped. The superchargers groaned. At those altitudes, the Luftvafa was fighting against physics itself. Then came the rumors. Reconnaissance reports from occupied France and the Netherlands described a new escort fighter, sleek silver, long-legged.

It flew with the bombers all the way to Germany and back again. At first, the Luftvafa dismissed the reports as propaganda. No piston engine could hold power that high. It wasn’t possible. But the wreckage told a different story. Crashed P-51s collected from Normandy and the Low Countries bore engines unlike anything German intelligence had cataloged. The captured technical reports baffled the analysts.

One memo dated February 1944 read, “American Pursuit aircraft maintained sea level performance at 9,000 m. Observation cannot be explained by known supercharger design.” The note was quietly dismissed. The analysts must have been mistaken. That denial was more than pride. It was faith. To German engineers, every improvement required refinement, not reinvention.

Their culture of precision made them masters of the detail and prisoners of it. Their factories, already strained by bombing, could not mass-produce complexity at scale. Each DB 605 was handtuned, adjusted by craftsmen who understood its every vibration. Across the ocean, Packard and Pratt and Whitney were doing something unimaginable, building engines that didn’t need to be tuned at all.

By 1943, the Americans were producing more engines each month than Germany could in a year. The Luftwaffa’s belief in artisal perfection had become a strategic liability. The United States believed in reliability through repetition, in power through production. Every engine that rolled off an American assembly line was not an individual work of art.

It was one cell in a living machine identical to thousands of others, ready to be replaced, repaired, or improved overnight. Inside the engineering community of Germany, whispers began to spread. Pilots returning from combat described enemy fighters that climbed as if pulled by invisible hands. See for ly and kind of they said they lose no power in meeting rooms filled with cigarette smoke and frustration.

Project leaders at Dameler Benz and Junkers began to argue over priorities. Should they pursue high alitude superchargers or jet propulsion or even steel from captured designs? But resources were collapsing and the war economy was breaking down. No one could afford to think 10 months ahead. They were fighting week to week.

And yet in their pride, they still believed they understood engines better than anyone else on Earth. When news arrived that a nearly intact American P-51 had been recovered near Ludvig Hoffen, the order was immediate. Send it to Reclan and find out what the Americans had done. That decision would lead to one of the most humbling discoveries in modern engineering.

A moment when German precision met American pragmatism and lost. The narration slows. They thought they had reached the limit of the piston engine. What they were about to uncover was proof that the limit had already been broken and not by them. Now the voice turns to the audience. If you believe that arrogance was Germany’s real weakness, comment number one. If you think the Allies simply built more, not better, like this video.

Because before the P-51 arrived at Ricklin, the Luftwafa believed perfection was invincible. They were about to learn how wrong that belief could be. On the morning of June the 13th, 1944, a column of German military trucks moved slowly through the countryside south of Ludvig Hoffen. In the open truck bed wrapped under a scorched tarpollen, lay the most valuable wreck the Luftvafa had seen in months.

The P-51B Mustang serial number 4312101 had been brought down by flack the previous afternoon while escorting a formation of B7s. The pilot, Lieutenant Charles Bailey of the 354th Fighter Group, had bailed out and been captured alive. His aircraft, remarkably, had not exploded or burned. The engine was intact, the fuselage largely unbroken.

To the men guarding it, it was just another downed enemy plane. To the engineers waiting at Reclan, it was a miracle. By the time the convoy reached the testing grounds 2 days later, the Mustang already had a file number object 512. Two mechanics watched as the truck backed into hangar 5.

The doors shut behind it, sealing the room in half darkness. Inside, the air smelled of oil and wet metal. Colonel Wolf Gang Teal, chief of flight testing, paced around the aircraft in silence. The silver skin was dented, but not shattered. The canopy glass had spiderweb cracks. The tires were still inflated. Every bullet hole was carefully marked in chalk.

To the machine felt more alive than dead. Orders came swiftly. No dismantling until every measurement was recorded. A team of engineers, draftsmen, and photographers assembled around the aircraft. They mapped its dimensions, traced the curvature of the wings, documented every rivet line. Nothing about the Mustang’s shape seemed remarkable. Its fuselage was slender.

Its wings were elliptical, and its surfaces showed none of the ornate craftsmanship found on German aircraft. But beneath the skin lay something the Luftwafa had never built a power plant that could make this shape climb to 40,000 ft and fight all the way there. The first step was to remove the propeller and engine cowling.

Technicians loosened the bolts and slid away the panels, revealing a dense labyrinthine structure of tubing and castings. Fuel lines wound like veins. The supercharger casing, massive and gleaming, sat deep in the belly. On the data plate, one word drew every eye. Packard. Not Rolls-Royce, not British, American.

A factory in Detroit had built this engine and it looked nothing like the handpished DB 605s that the Germans considered state-of-the-art. Hans Fay was among the first to inspect it. He traced the air ducts with a gloved finger, following their improbable route down the fuselage into an intercooler back up again through a second compressor stage and then into the cylinders. It made no aesthetic sense.

German engines were compact, integrated, tidy. This was chaotic, overbuilt, industrial. But the more they studied it, the more the chaos revealed its purpose. The airflow path was long because it was cooled twice. The second supercharger stage created a pressure environment unheard of for a piston engine.

Fay realized with a kind of reluctant admiration that the Mustang didn’t fight the thin air, it ignored it. A few days later, the Luftwaffa command sent a team of metallurgists to examine the alloys. They discovered lightweight magnesium components in the compressor and a nickel chromium blend in the turbine wheel that resisted heat far beyond German tolerances.

These weren’t exotic metals. They were production materials perfected through industrial consistency. The Americans hadn’t built a better engine by invention, but by iteration. Thousands of identical parts produced with almost machine-like reliability. The discovery was quietly devastating. The engineers decided to test the power plant.

They mounted the Merlin on a static stand outside the hanger, connected the fuel lines, and started it under controlled conditions. The roar filled the valley. At 25,000 ft of simulated altitude, the instruments read full power 1 695 horsepower. No loss, no detonation, no hesitation. The data stunned the observers. The DB 605 lost nearly 40% of its rated power at that height. The Merlin did not lose a single fraction.

Inside the test log book, the German recorder hesitated before writing the results. He crossed out unmug impossible and replaced it with bistatic confirmed. That single word meant the Luftwafa had just seen proof that the Americans had solved the problem of high altitude flight while Germany was still trying to design its way out of gravity. By July, the P-51 had been completely disassembled.

Every component was weighed, measured, and photographed. Engineers cataloged over 20,000 parts. Yet the more they studied, the less they understood. The Mustang’s construction philosophy contradicted everything they had been taught. Instead of perfection, there was tolerance. Instead of delicate balance, there was brute stability.

Even the rivet spacing was irregular by German standards, but somehow the structure was stronger. FaZe report concluded with a line that circulated quietly through the engineering divisions. It is not a machine of genius. It is a machine of purpose. That sentence would haunt many who read it. The narrator’s tone would narrow. Here, calm and deliberate.

What the Germans didn’t know was that the Mustang was not designed for beauty, nor for speed alone. It was designed for altitude, range, and replaceability, the three things a total war demanded. And then the voice turns outward, challenging the viewer. If you believe the Germans were the victims of their own obsession with perfection, comment number one.

If you think the Americans simply got lucky with one design, like this video. Because as the engineers at Reclan pulled apart the P-51 piece by piece, they weren’t just examining an engine. They were dissecting the idea of what progress meant. The test cell at Wland roared to life again in late July 1944.

Outside the Merlin Packard Vite 1650 sat chained to its static mount exhaust stacks aimed toward a concrete wall blackened by repeated runs. The sound was not merely mechanical. It was elemental, a pressure that vibrated through the bones. Inside the control room, a halfozen engineers leaned over instrument panels, watching needles climb past the limits of familiarity.

Hans Fay adjusted his headset, listening to the rising pitch. At 3,000 revolutions per minute, the tone sharpened a shriek layered with an undertone like thunder. The barometric compensator fed false altitude into the carburetor intake, simulating flight at 25,000 ft.

On every German engine they had ever tested that point marked decline fuel mixture, faltering boost, pressure, collapsing horsepower, bleeding away into thin air. But this time, the instruments refused to obey the old laws. The boost gauge held steady. The manifold pressure actually rose. Temperature readings stabilized. The engine didn’t gasp for air. It demanded more.

Face stared at the data in disbelief. He leaned into the microphone. Increase boost by 10%. The technician complied. The wine deepened into a tone that was almost musical, a steady crescendo with no tremor, no vibration. The British had called it the Merlin. The Americans building it under license had turned it into something else entirely.

The Packard Feeb 1657 wasn’t simply a copy of Rolls-Royce craftsmanship. It was an evolution of it. The heart of the miracle lay behind the engine block in a massive snail-shaped assembly of aluminum and steel. It was the two-stage two-speed supercharger, an air compressing heart, that made the Merlin behave like a breathing organism rather than a machine.

In most engines, a single supercharger stage compressed incoming air before combustion. At higher altitudes, that air grew thin and the compressor lost its bite. The Merlin used two. The first stage grabbed the air. The second crushed it further, then forced it through an intercooler where temperature dropped before being inhaled by the cylinders.

The result was a consistent pressurized feed as if the engine carried its own atmosphere wherever it flew. To the German engineers, it felt like sorcery. Their own DB 605 and Jumo 213 used mechanical superchargers that required perfect calibration. The slightest misalignment caused detonation heat or loss of power. The American design tolerated imperfection.

The air ducts were wide, the materials coarse, the system self-regulating. Instead of precision, it relied on resilience. A centrifugal clutch automatically shifted between high and low blower speeds depending on altitude. No pilot input, no engineer adjustment. It was an intelligent mechanism in an age before electronics.

Fay dismantled the supercharger housing and set the impeller on the table. The blades curved like a turbines, each one balanced but not polished. The Germans used machined steel. The Americans used cast aluminum lighter and easier to make. Fay noted the part number stamped crudely on the hub Packard Motor Co. Detroit m.

It looked industrial, almost vulgar, yet the tolerances were perfect. The impeller spun freely with no measurable wobble. He examined the intercooler, two rectangular heat exchangers positioned behind the supercharger. Coolant lines circulated glycol through the cores, dissipating heat before the compressed air reached the cylinders.

That simple step solved the ancient enemy of high alitude power pre-ignition. German engines relying on single stage designs always faced overheating under sustained boost. The Merlin’s twin hearts of aluminum kept it breathing cool and clean mile after mile, hour after hour. The data from the tests stunned everyone.

At simulated altitudes above 30,000 ft, the Merlin still delivered more than 1,600 horsepower, almost its full sea level rating. The DB 605, at the same height, could barely manage $1,000. And yet, the Merlin weighed nearly the same. The secret wasn’t more metal. It was smarter air. In the Rland briefing room, engineers debated endlessly over the findings. One officer insisted the readings were false, that the gauges were miscalibrated. Fay shook his head.

We checked them three times. He said, “The air is thinner, but the engine does not care. It breathes like a jet.” The phrase spread through the facility. It breathes like a jet. At the time, Germany’s first jet fighter, the MI262 was still in limited production, plagued by unreliable turbines that burned out after 20 hours. The irony was bitter.

Their enemy had built a piston engine that emulated jet behavior while their own jets could barely stay aloft. Fay’s final test was the one that convinced everyone. He connected a strooscopic tachometer to the impeller shaft set to record its rotational speed. At full boost, the second stage impeller spun at 25,000 revolutions per minute.

At that rate, the tips of the blades approached transonic velocity. The air entering the manifold reached pressures equivalent to 61 in of mercury, nearly double what the DB 605 could safely handle. The sound alone told the story. A piercing scream layered over the deep pulse of the cylinders and acoustic blend halfway between piston thunder and turbine wine.

When the test ended, the engineers stepped outside into the cool evening air. The hanger smelled of hot oil and ozone. Fay stood by the still cooling engine and realized something he couldn’t put into his report. This was not an aircraft engine in the old sense. It was an industrial organism engineered for mass replication, not for individuality.

The Americans had found a way to turn life itself into production. He dictated his notes into the recorder, “The construction is crude but effective. The concept supercharger with intercooler is beyond our capacity for volume manufacture. The results are conclusive. The Americans have made altitude irrelevant.

His voice trailed off around him. The war was collapsing. The Luftwaffa’s airfields were under constant attack. Factories were burning. Yet the data was undeniable. At 30,000 ft, the Merlin gave the Americans command of the sky. The narrator’s tone shifts to reflective calm. For the men at Reclan, it was not just an engineering defeat. It was an existential one.

The P-51’s engine proved that perfection was no longer the path to victory. Adaptability was. Visuals fade to archival film of American production lines. Women in overalls tightening bolts on engines identical to the one tested at Recklin. Thousands of them. Rows of V1650s mounted on test stands. Flames bursting from exhausts in synchronized rhythm.

Narration continues. Each one of these engines was identical. Each breathed with the same measured fury. Each could take the fight to the edge of the stratosphere and bring its pilot home again. The closing moment of this section would return to the hangar at Recklin Nightfall, settling through the open doors.

Fay closes his notebook, extinguishes the lamp, and looks back once more at the dark silhouette of the engine. We build art, he murmured to a colleague. They build power. Then the narration turns outward addressing the viewer directly. If you believe that raw intelligence beats beauty, comment number one. If you think perfection is still worth chasing, even in defeat, like this video, because what the Germans discovered in that hanger wasn’t just an engine that defied altitude.

It was the moment they realized the war of ideas had already been lost. By August 1944, the results from Reckland had spread through Germany’s remaining aviation circles like a whispered confession. Everyone had seen the numbers. Everyone knew the truth. The Americans had done something that the Reef’s most gifted engineers could not. They had made power reproducible. Still, no one wanted to believe that a solution so crude looking could be so far ahead.

In the halls of Dameler Ben’s Junkers and BMW meetings stretched long into the night as engineers tried to design their way back into relevance. At Desau, the Junker’s motor in Vera received a classified order replicate the American twin stage supercharger system using the Yumo 213E engine as a base.

The request came directly from the RLM Reichs Luftvart Ministerium, the Air Ministry. The objective was clear. develop an altitude compensating system comparable to the Packard VI 1650. In other words, copy the engine that breathed like a jet. They began with enthusiasm. The first drawings were produced in early September.

German draftsmen measured the ratios from the Wrestling Reports impeller diameters, pressure stages, intercooler flow rates, and tried to fit them into the Jumo’s tighter crank case. But each improvement led to another problem. The Jumo’s supercharger gears couldn’t handle the rotational speed of the American system. The bearings overheated at high altitude.

The magnesium alloy available in Germany was impure corroding within hours of exposure to compressor heat. On September 17th, engineers conducted the first test of their E2 Versuk prototype. The engine started cleanly boosted for 12 seconds and then detonated in a flash of orange. The impeller shattered. Fragments tore through the test cell wall. Two technicians were injured. The official cause metallurgical fatigue.

The unofficial one, desperation. Hans Fay, who had overseen the Reclan trials, was summoned to inspect the wreckage. He found scorched shards of compressor blade embedded in the concrete. His report was restrained almost surgical failure due to material quality. German alloys insufficient for sustained boost above 1.

6 6 ATA reproduction not feasible without chromium nickel composition equal to American standard in plain terms they didn’t have the metal the war had starved them of the very elements nickel cobalt malibdinum that the Packard engine consumed by the ton while struggled with chemistry Dameler Benz fought physics their engineers tried to graft a second supercharger onto the DB 605’s rear casing creating a two-stage variant known internally as the DB 605L. It worked on paper.

In practice, it required a redesign of the entire oil system cooling system and reduction gearbox. Production would take 9 months. Germany didn’t have 9 weeks. Allied bombers were reducing cities to dust faster than blueprints could be printed. At Stoutgart, one frustrated engineer compared their efforts to rebuilding a cathedral during an air raid. He wasn’t far off.

The factories that had once been temples of precision were now scarred ruins. Skilled machinists were dead or conscripted. Electricity failed without warning. Each new attempt to replicate the Merlin ended not in progress, but in smoke. The failure went deeper than material shortages. It was philosophical. The Americans had designed their engine backward from production to purpose. Every bolt, gasket, and duct was standardized.

Each part could be built by a dozen subcontractors and fit perfectly when assembled. The Germans still worked in the old artisan tradition where each engine was a unique creation tuned by hand, adjusted by ear. There was no room for imperfection and thus no margin for speed.

One report from Dameler Benz dated October 2nd captured the despair in numbers. To build one DB 605 required an average of 2100 man hours. A single Packard Merlin required 450. That difference wasn’t just efficiency. It was victory measured in time. The RLM tried to push development forward regardless.

A memo to Junkers requested simplified supercharger prototypes using alternative impeller designs. The engineers complied, fabricating units from soft steel and even recycled aircraft scrap. The compressors lasted less than 2 minutes before seizing. Meanwhile, American factories in Detroit and Chicago were producing 400 new Merlin every day.

Their assembly lines glowed through the night, powered by unbroken supply chains and a workforce that never stopped. The same women riveting engines at Packard were assembling B24s at Willow Run, creating an industrial ecosystem the Reich could only dream of. Each time a German engineer blew up a prototype, 10 new Mustangs took flight somewhere over Europe. Fay summarized the futility in his last technical note.

Before the wars end, replication not possible under current conditions. The design is understandable, but the system supporting it does not exist here. That final line was the essence of defeat. They could grasp the idea, but not the infrastructure. The genius of the Packard Merlin wasn’t in its blueprint. It was in the nation that built it. The narrator’s tone here turns almost eligic.

Germany’s engineers had discovered the secret of the Mustang’s heart, but not the soul of the country that made it. What they lacked wasn’t intelligence. It was abundance. Cinematically, this section would fade between scenes. A German test stand exploding in sparks. An American factory line roaring with hundreds of identical engines.

Two worlds separated not by design, but by capacity. By December 1944, the Luftwaffa’s engine division stopped all attempts to copy the Merlin. The Mi262 jet was now their last hope, though its Yumo 004 engines burned out in hours. Fay was transferred to an underground lab outside Munich to evaluate captured Allied technology. When asked if the Merlin design could be repurposed for a German fighter, he replied simply, “Even if we could build one, they would build a thousand.” The narrator’s voice softens to reflection.

For every problem Germany tried to solve with precision, America solved with production. The war of invention had become a war of iteration, and only one side had the rhythm to sustain it. Then, as always, the story turns to the audience.

If you believe that innovation without industry is just a dream comment number one, if you think the Germans could have matched the Americans given more time, like this video, because at Reclan, in the months that followed, every attempt to copy the engine that breathed like a jet ended the same way in smoke, silence, and realization.

By the spring of 1944, the sky over Europe had become an equation. It was written in speed, altitude, and horsepower. And for the first time in the war, the variables no longer favored Germany. The Luftvafa’s fighters, once kings of the air, were now gasping for oxygen in battles they could no longer reach. On March 6th, 1944, the United States 8th Air Force launched its first daylight bombing raid on Berlin.

Nearly 700 B7s and B-24s rose from English airfields before dawn, escorted by more than 800 fighters. Among them were the new P-51B Mustangs powered by the Packard Merlin, the same engine that had left the engineers at Reclan speechless. As the bombers climbed through 30,000 ft, the fighters stayed with them. That simple fact, those three words stayed with them, changed the course of the war.

Before the Mustang bombers had always flown alone over Germany, Spitfires P38s and Thunderbolts could protect them only partway turning back when fuel ran dry. The Luftvafa would wait beyond their range, then strike with impunity. That strategy died the moment the first P-51 crossed the Rine without turning around.

When German radar screens lit up that morning, operators assumed the escorts would peel away. They didn’t. At 27,000 ft over Magnabberg, the first wave of Faula Wolf 190s rose to meet the bombers. Their climb was steady at first, but thin air quickly robbed their engines of strength. The DB 605s that powered the Messers began to falter above 26,000 ft, producing little more than a,000 horsepower. The Mustangs, by contrast, held nearly full power.

In cockpit recordings from that day, an American pilot’s voice crackles through the radio, still pulling 61 in at $29,000. She’s breathing fine. The Merlin didn’t gasp. It inhaled. The German formation dissolved under the first attack. The Mustangs dove like falling stars. 850 caliber guns pouring fire into the 190s, struggling to climb.

Within minutes, 12 German fighters were down. For the bombers, it was the first mission to Berlin, where the escorts arrived with them and left with them. Of the 600 bombers dispatched, only 69 were lost a number unthinkably low compared to the massacres of 1943. In the operations room of Luft Fla Reich, the reports arrived one after another.

Enemy single seaters at 30,000 ft cannot engage above 26. fuel exhausted during pursuit. Each line read like a death sentence. The Luftwaffa had spent years mastering the tactics of dog fighting, energy management, and precision gunnery. None of it mattered when their engines couldn’t breathe. By May 1944, Allied intelligence began counting German losses with mathematical precision.

From March to August, the Luftvafa lost more than 2,200 fighter aircraft, nearly half of its operational strength. The cause was not just superior numbers, but superior altitude. P-51s dominated the thin air where no German piston engine could survive.

A British intelligence officer summarized it bluntly in a report to London, “Their engines die before our pilots do.” The Merlin’s advantage was measurable and merciless. At 30,000 ft, a P-51 maintained 437 mph. A BF 109G barely managed 360. That 70-mi gap turned combat into execution. German pilots tried to dive to escape, but the Mustang’s airframe, clean and balanced, followed with ease. In every direction, speedrange endurance, the equation favored the Americans.

On June 29th, 1944, Lufafa ace Johanna Steinhoff wrote in his log book, “After surviving another failed interception, we cannot reach them. Our planes fight against air itself. Above 8,000 m, we are ghosts chasing ghosts. For every Mustang in the sky, there was an invisible network behind it. refineries, factories, convoys, and workers who built fueled and maintained a system of endless replacement.

When a P-51 returned with engine damage, its Merlin was swapped within hours. When a messmitt limped home, it waited weeks for a single replacement part. Industrial tempo had become tactical power. The narration would tighten here. The Luftwaffa fought like swordsmen in a world that had moved on to rifles. They still believed in the duel. The Americans believed in the supply chain.

Cinematically, the scene would intercut between dog fights over Germany and assembly lines in Detroit. Each Mustang engine rolling out identical to the one before it. The precision of mass production mirrored the precision of aerial combat. By late summer, the Luftwaffa began rationing fuel. Pilots trained for only 30 minutes before being sent into battle.

The once-feared Yageshwatter units JG26, JG11, JG-54 were down to half their strength. Every sorty risked annihilation. The P-51s ruled the stratosphere, escorting bombers by day, hunting by dusk, sweeping airfields by dawn. Even Adolf Gand, the Luftvafa’s general of fighters, admitted in a post-war interview, “From the moment the Mustang appeared, we had lost control of the air. It was the perfect machine at the perfect time.” The numbers confirmed it.

In 1944 alone, P-51s destroyed more than 4900 enemy aircraft in air combat, the highest single-year total of any fighter in history. And beneath every victory lay the same quiet secret and engine that refused to lose power when the world grew thin. At Reclan, Hans Feay received the combat data with quiet resignation. He had predicted it.

In his final wartime report, he wrote, “Operational experience confirms laboratory findings. At 9,000 m, the V1650 retains nearly complete efficiency. German aircraft cannot engage at equivalent altitude. The last line was both technical and poetic. They have conquered the sky by learning to breathe where we cannot.

The narrator’s voice would lower here, reflective and final. The Luftwaffa had entered the war, believing that superior pilots and superior machines could decide victory. But by 1944, it wasn’t bravery that ruled the sky. It was airflow metallurgy and the relentless rhythm of factories thousands of miles away.

As the section closes, the viewer sees archival footage of contrails crossing above Germany. White lines etched against the blue mile high handwriting of defeat. Then the call to audience returns, anchoring the human question inside the technical story. If you believe that wars are won not by heroes but by the hands of those who build comment number one.

If you still believe courage could have changed the outcome like this video. Because when the Mustangs escorted the bombers over Berlin, it wasn’t just a battle for airspace. It was a demonstration that the side that could breathe higher, longer, and faster would decide the fate of the world below. The war ended not with an explosion but with silence.

The skies that once trembled with the roar of Merlin engines now carried only the wind. In the ruins of Germany, factories that had built meers and junkers stood hollow. Their machine tools stripped away or melted for scrap.

The reckland test center once the cathedral of Luftwaffa engineering was reduced to rubble and ash. Amid the collapse, a few surviving engineers were quietly approached by the victors. Men like Hans Fi, who had once dissected the captured P-51, now found themselves working for the same nation whose machines had destroyed theirs.

In 1946, Fay was flown to the United States under Operation Paperclip, not as a prisoner, but as an asset. The Americans wanted knowledge, data, and minds that understood the frontiers of piston and jet propulsion. He arrived at Wrightfield in Ohio carrying a single briefcase of notes and one haunting question. How had America done it? When he first walked through the hangers, the answer stared back at him.

Rows of engines identical to the one he had tested at Reclan, lined up like soldiers, each one ready, each one alive. He was later assigned as a consultant for North American Aviation in Englewood, California, the very company that had built the Mustang. There, among the noise of peace time production, he met the men who had designed it.

They were not professors or theoreticians. They were practical engineers, welders, machinists, and former race car builders. They spoke of balance sheets, tolerance margins, and supply chains more often than of aerodynamics. To Fay, it was like stepping into a different civilization, one where genius was measured not in precision, but in repeatability.

One afternoon in 1948, during an engine test at the facility, Fay was invited to watch a restored Packard built Merlin V1650 startup. The technicians treated it like an old friend. When the propeller spun and the first coughs of ignition turned to a rising scream, Fay closed his eyes. The sound was exactly as he remembered, the same clean, unbroken tone that had once filled the hangar at Recklin.

He realized he no longer heard defeat in it. He heard continuity. The engine had outlived the war, outlived the nations that built it, and now powered aircraft meant only for air shows and training. He kept a private notebook during those years later found among his papers. On one yellowed page he had written, “Perfection is fragile.

Production is immortal.” Beneath it another line. The American victory was not born in a laboratory. It was born in the rhythm of machines. The narrator’s voice would soften here, turning from the personal to the universal. The Merlin and the Messesmidt were both products of genius, but one was designed to be perfect once, the other to be perfect a thousand times. The difference was philosophy.

The Germans worshiped the craftsman’s hand. The Americans trusted the facto’s pulse. As decades passed, the surviving Mustangs became relics of a vanished world. Yet the lessons they carried endured in every jet turbine and every industrial process that followed. The war had forced humanity to choose between the art of making and the art of multiplying. The nations that mastered both shaped the century.

In 1963, Hansfi visited the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. There, under polished lights hung a fully restored P-51D Mustang. its propeller glinting like a silver compass frozen in time. The placard beneath it read, “Powered by a Packard-built Rolls-Royce Merlin 1695 horsepower service ceiling, 41900 ft.” Fay stood in silence for a long time.

When a curator approached, he smiled faintly and said, “I know this sound. I once thought it was the enemy. It was actually the future.” The narration closes on his reflection, bridging the war and its moral echo. The men who built the P-51 and those who tried to copy it were driven by the same dream to conquer the limits of flight.

But only one side understood that simplicity multiplied becomes strength. Then, as the camera lingers on the restored mustang’s nose, art gleaming beneath museum lights, the voice addresses the audience one final time. If you believe that progress is born from collaboration, not competition, comment number one.

If you believe that every machine carries the story of its maker, like this video. Because the war between the Merlin and the Mesishmmit was never just a contest of engines. It was a contest of philosophies. And the one that breathed longer, higher, and wider still echoes every time a piston engine turns over somewhere in the silence of peace.