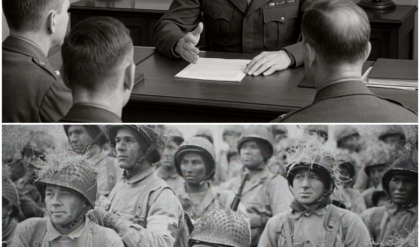

By the winter of 1944, thousands of African-American soldiers were scattered across the battlefields of Europe. Most served in segregated units, drivers, engineers, and labor battalions, rarely allowed near the front lines. Yet, as the Allies pushed deeper into Germany, chaos blurred those boundaries.

Some black troops were captured in mixed formations or after ambushes, thrown into P camps that had never seen men of color before. German guards raised under Nazi racial doctrine often didn’t know what to make of them. Propaganda had painted American soldiers as racially inferior. Yet here they were disciplined, resilient, and wearing the same uniform as white officers.

That contradiction created confusion and sometimes a dangerous curiosity. Inside the barbed wire, survival depended on silence and routine. 5 minutes. Prisoners were expected to obey, eat little, and endure the cold. But for a handful of black PS who spoke or understood German from school, family, or time spent in Europe before the war, their knowledge became both a weapon and a risk.

They could overhear the guards conversations, sense the tension between Nazi ranks or predict when punishments were coming. Some used it to warn fellow prisoners, others to quietly earn favors. Extra bread, a blanket, a few minutes of trust. But the moment they revealed that ability, everything changed. To the guards, a black man speaking fluent German defied every stereotype the regime had drilled into them. Some reacted with respect, others with humiliation or violence.

Either way, the illusion of superiority cracked, if only for a moment. The walls of language that divided capttor and captive had shifted. But what came next would depend on which side of that understanding they stood. For the Vermuck and Luftvafa guards, captivity followed its own set of unspoken rules. Most had never seen African-Americans before.

They’d been taught through propaganda films and classroom indoctrination that the United States was a chaotic, mixed nation, weakened by race. When these same soldiers found educated, fluent English speakers in uniform, they already felt the first crack in that belief. But when a black prisoner replied in perfect German, the illusion shattered completely.

Accounts from Red Cross reports and postwar testimonies describe scenes of stunned silence in the camps. Some guards asked how they had learned the language. Others searched for tricks, assuming the man was mocking them or pretending, but fluency is hard to fake. A few German officers even carried brief conversations. intrigued by these prisoners who could quote Gerta or sing German folk songs they’d learned in school back home for men like Private Leon Thompson and the real soldiers his story represents that fluency offered a thin edge of safety they could sometimes ease tension predict searches or understand camp

gossip about Allied advances yet it also brought danger speaking German too well could draw the attention of Gestapo officers or SS patrols who saw such intelligence as defiance. Many black PS described being moved to separate compounds, interrogated longer or accused of espionage simply because they knew too much.

Still, others found unexpected moments of humanity, a guard who quietly slipped food, or one who whispered that the war would soon end. Inside those fences, language became more than words. It was survival, identity, and quiet rebellion against a system built on ignorance. angles, perspectives. Every P camp in Germany had its own rhythm. Fear, boredom, and the slow erosion of hope.

But when a black American prisoner spoke fluent German, that rhythm broke. For fellow PS, it was astonishing. In a world defined by rank and race, here was someone who could suddenly read the enemy’s tone, sense their doubts, and sometimes change the mood of a room with a single phrase. To many of the white American captives, it was the first time they’d seen their black comrades hold unexpected power.

These were men who back home couldn’t sit in the same cafes or attend the same schools. Yet in a German camp, their knowledge gave them authority. Some guards treated them differently, not as inferiors, but as men who could understand. That shift didn’t erase racism, but it blurred it long enough for truth to slip through. From the German perspective, it was unnerving.

Nazi racial ideology depended on certainty, on a strict hierarchy where language and intellect were proof of worth. A black man speaking fluent German challenged that foundation. It left some guards angry, others embarrassed, and a few quietly questioning what they’d been taught. In rare cases recorded after the war, German officers admitted that these encounters made them uncomfortable in ways the front lines never had. It was as if the war had turned upside down, one recalled.

The prisoner could see us clearly, and we no longer understood ourselves. For the prisoners, that clarity came at a cost. Knowledge brought suspicion. Understanding the language of their capttors meant hearing every insult, every plan, every threat, and staying silent through it all. Angles, perspectives. Not every story ended with understanding.

Some of the most haunting accounts came from those who learned that knowing too much could turn survival into peril. A few guards saw linguistic intelligence as insolence, a challenge to the authority that kept their fragile world intact. For them, a black man speaking fluent German wasn’t impressive. It was threatening. Private Thompson’s experience mirrors many such encounters.

One afternoon, when he corrected a guard’s translation of an English phrase, the camp fell silent. The guard’s face hardened. Within hours, Thompson was transferred to a smaller compound under questioning. Interrogators wanted to know where he’d learned German, who had taught him, and whether he was trained by US intelligence.

To them, it seemed impossible that an African-Amean could speak their language without hidden motives. For others, the experience was quieter, but just as revealing. Some guards began to confide small things. complaints about food shortages, fear of Allied bombing raids, or even worries about their families back home.

In those moments, the war’s racial walls cracked. Two men, supposed enemies, found themselves talking like human beings caught in the same storm. In Red Cross inspection notes, there are rare mentions of colored prisoners who understood German well and could converse politely. These details were often overlooked, buried in bureaucratic language, but they offer glimpses of connection that defied ideology.

To speak the enemy’s tongue was to see the war from both sides, to witness cruelty and empathy tangled together. For black PS, it became a mirror, showing them not just the prejudice of their captives, but also the uncomfortable reflection of the country they fought for. Climax turning point. The turning point came when the camps began to fracture under the weight of Germany’s collapsing front. By late 1944 and early 1945, Allied bombers roared overhead almost daily.

And news of Soviet advances trickled even into the most remote prison compounds. Guards grew tense, food grew scarce, and discipline began to crack. For prisoners like Leon Thompson, that chaos changed everything. One night, as sirens wailed and search lights swept across the snow, he overheard two guards whispering near the barracks door.

They spoke in hurried, frightened German, planning to abandon their posts if the allies drew closer. They mentioned roots, trucks, and a secret cash of supplies. Thompson understood every word. By dawn, he told a British officer in the next hut. Carefully, quietly, one know what he’d heard. Within days, that information spread through the camp and prisoners began preparing for what might come.

A hasty evacuation or an opportunity to escape. When the guards realized their words had been understood, panic set in. Thompson was pulled out for questioning again, but this time the interrogators weren’t angry. That mean they were afraid. They wanted to know what else he’d overheard, how many prisoners spoke German, whether rumors about an Allied breakthrough were true. The balance of fear had shifted.

The same man they once mocked now held the one thing they needed most, information. For the first time, Thompson felt the strange inversion of power that language can create in war. The guards who once ordered him around now spoke softly, careful not to reveal too much, and in their eyes he saw something new. Not hatred, not respect, but quiet uncertainty.

Shall I continue with climax turning point? Days later, the camp erupted in confusion. Allied tanks were rumored to be less than 30 km away, and the guard’s authority was crumbling. Orders changed by the hour. Some prisoners were marched out under threat of fire. Others hid in cellars waiting for liberation. Amid the chaos, Thompson’s understanding of German became more than a survival tool.

It became the difference between life and death. He heard a young sergeant shout that the SS planned to shoot problem prisoners before fleeing. The words weren’t meant for foreigners, but Thompson understood them and acted fast. “Whisper by whisper,” he warned the others, guiding them toward the far end of the compound where the guards rarely patrolled.

When trucks finally rolled through the gates that night, only a handful of Germans remained to oversee the evacuation. Thompson stayed silent as the column moved into the woods. He caught fragments of panicked German talk of surrender of Americans nearby of no point in fighting anymore. When gunfire broke out from the distance, the guards scattered. The prisoners ran.

By morning, they stumbled upon a forward Allied patrol. Exhausted, half starved, but alive. Thompson tried to explain what had happened, but his voice trembled. He had lived weeks hearing the enemy’s secrets, knowing that a single word in the wrong moment could end him. When liberation came, many PS cheered. Thompson simply stood still, listening to the foreign language that had haunted him for months, now spoken freely, without fear.

In that quiet moment, he understood something larger than survival, that the war had taught. When the camps were finally liberated in the spring of 1945, the stories of black prisoners barely made it into the reports. The focus was on troop numbers, medical needs, and the horror of what had been found. Yet behind those statistics were men like Leon Thompson, men who had lived through two wars at once. One against the enemy and one against the prejudice of their own army.

For months after liberation, they were processed, deloused, and questioned. American officers stunned to find black PS among the survivors often asked the same thing. How did you end up here? The idea that African-Ameans had fought, been captured, and survived in Europe contradicted the segregated image the military still clung to.

Some soldiers spoke about their treatment, how German guards had mocked them, but also how their fluency in the language had sometimes saved their lives. A few mentioned conversations that had stayed with them. A guard admitting he no longer believed in Nazi ideology. Another whispering that Hitler’s Germany was doomed.

For the first time, these men had seen the myth of racial superiority crumble from both sides. Yet, when they returned home, that understanding met a different kind of wall. Many disembarked their transport ships to find the same Jim Crow laws waiting for them, the same colored signs, the same restrictions. Their ability to speak German, their experience as PS, even their acts of quiet resistance were rarely mentioned in military history. But among themselves, they remembered.

In letters and small reunions years later, they spoke of how language had once turned captivity into control and fear into strategy. Decades later, a few of those men began sharing their memories in interviews and veterans projects. Their stories were soft-spoken without bitterness, but filled with moments that rewrote what captivity had meant.

One recalled teaching a guard simple English phrases in exchange for scraps of bread. Another described translating a German broadcast for other PS, helping them realize that the war might soon end. Each story carried the same undercurrent. That language had been their quiet defiance. It wasn’t rebellion in the open. It was survival through understanding. They had turned what the enemy saw as weakness into something powerful.

Awareness, foresight, dignity. Historians who later studied these accounts noticed a pattern. Guards who interacted with multilingual black PS often displayed a kind of confusion, even restraint. It wasn’t compassion, but rather the shock of confronting a reality that Nazi ideology had denied, that intelligence and courage existed beyond race.

For a brief time behind barbed wire, that realization unsettled the hierarchy the regime had built its power on. Yet the American military rarely acknowledged these encounters. The records remain thin, the details scattered across personal memoirs and Red Cross archives. Still the echoes persist in family stories and museum exhibits and in the eyes of those few who lived long enough to tell them. For men like Leon Thompson, it was never about revenge or pride.

It was about being seen, about knowing that in the darkest hours of captivity, the human voice itself became an act of resistance. And in that small space between words, history shifted and quietly permanently. History often remembers battles and generals, but not the quiet intelligence of survival. The story of black PS who spoke fluent German isn’t just about language.

It’s about perception, dignity, and the fragile bridge between enemies who suddenly saw each other as human. In those frozen camps where silence could mean safety, words became both shield and weapon. Understanding the enemy’s tongue exposed cruelty, but also revealed fear. It proved that power built on ignorance could crumble with a single conversation.

When the war ended, those men returned to a divided America, carrying a truth few wanted to hear. That humanity can’t be measured by race or uniform. And that empathy, once learned in the hardest places, never fully leaves. Their voices, once whispered behind barbed wire, remain proof that even in captivity, understanding is its own kind of freedom.