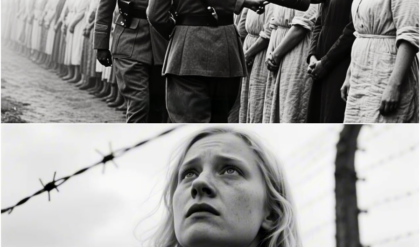

Cast out by her cruel, noble father for being too fat to marry, Livia is given to a slave as punishment. But what was meant to shame her becomes the first time she’s truly loved. Livia hit the stone floor hard, her elbows scraped raw, her knees jarred. The heavy oak doors slammed behind her with a finality that sounded like thunder in her chest.

She scrambled to sit upright, her long gown wrinkled and dusty, her curls trembling where they clung to her damp cheeks. The guards outside didn’t spare her a second glance. The punishment had been delivered. Their part was over. Inside the hall, Lord Cashin’s voice still echoed in her skull. You shame this family. Let him have you. Perhaps a few weeks of humiliation will teach you to eat like a lady and behave like one.

And that was it. No more arguing. No tears softened his heart. No pleading. Livia was no longer the noble daughter of Veilmont’s most powerful merchant. She was now property given away like something useless, something broken. Her vision stung as she looked up at the man standing across from her. He was barefoot.

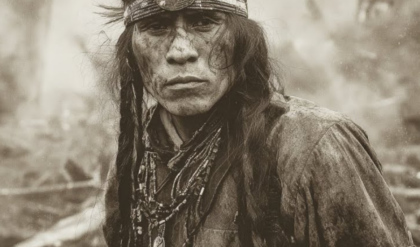

Dirt clung to his hands, and his shirt, if it could be called that, was tattered, hanging off his shoulders. The cuffs of his trousers were frayed, and a long scar ran down his forearm, visible even in the flickering lamplight of the servant quarters. But his eyes, they weren’t cruel. They weren’t mocking. They were stunned.

He stared at her like he didn’t know whether to help her or kneel. His name, she remembered faintly, was Celas’s, a stable hand turned slave bought from the mountains after a famine forced the poorer folk to trade sons for bread. She’d seen him only twice before, once when she was a child, peering from a carriage, and another time just last week when her father barked at him to shovel manure faster.

“Now somehow he was to be her keeper.” You don’t have to kneel,” she said, her voice shaking more than she liked. “They made it sound like I’m yours now.” He blinked slowly, like her words took a moment to settle. Then, with a faint crease in his brow, he stepped forward. Not close enough to frighten her, but near enough she could smell the hay on his skin and the warm earth on his breath. “I don’t want a gift,” he said finally, voice low and unsure.

I didn’t ask for this. Neither did I. They stood in silence, both watching the other as if expecting the ground to shift beneath them. Then Livia’s stomach growled loudly. She pressed her hand to it mortified, but Celas’s only turned toward the small hearth in the corner. Without a word, he grabbed a tin pot and filled it with water.

“I’ll make broth,” he said. She stared at him, confused. You’re not going to hurt me. He paused, then looked over his shoulder. Do you think I’m like your father? That silenced her. She lowered her gaze. No one had ever spoken of Lord Cash in that way. Not aloud. Not in front of her. But the quiet incas’s tone held no fear, only a kind of honest sorrow.

Like he’d seen too many men like her father, and had learned that the crulest punishments wore titles and gold. When the broth was ready, he handed her the warm cup and her hands shook as she held it. Livia didn’t speak as she drank. She wasn’t sure she could without crying, and he didn’t ask questions.

He simply sat cleaning tools by fire light, quietly humming some tune she didn’t know. That night, he gave her the cot and laid a blanket near the fireplace for himself. It was the first kindness she’d known in months. The next morning, Livia awoke to bird song and a cramp in her neck. She sat up too fast and regretted it immediately. Her back achd, her feet swollen, and her gown still smelled faintly of tears. Cela’s wasn’t in the room. Panic flared.

Had he told someone? Had he changed his mind? Would guards come take her back, back to that cold, marble prison of a home? But no. The door creaked open a moment later and Celas entered, arms full of firewood, face stre with morning sweat. “You’re awake,” he said simply. She nodded, brushing hair from her face. “I didn’t thank you for last night. You don’t have to.

” Still, something in his voice, something quiet and almost pained, made her wish she could. He laid out fresh bread and a few salted plums. Then to her surprise, he sat across from her like an equal. Livia blinked. You’re not afraid I’ll report you for sitting. He smirked faintly. You’re not noble anymore. That should have hurt, but it didn’t. Not when he said it like that.

Later, she offered to help sweep the barn. He looked at her in disbelief. You? Yes, me, she replied, rolling up her sleeves. I have hands, don’t I? She was clumsy, of course. She tripped over hay bales, shrieked when a mouse ran past, and once swung the broom so hard it hit the wall and snapped.

Celas tried to hold in his laugh, but he failed miserably, and the sound, his laughter, was warm like thunder filtered through sunshine. That evening, as they sat by the fire again, Livia asked the question that had been weighing on her all day. “Why haven’t you asked me anything?” He looked over, brow furrowed. Like what? Like what I did to be given away or what he told you or why I’m why I look the way I do.

Celas leaned back, stretching his long arms behind his head. I don’t care what he told me, and I’ve seen the way you look. There’s nothing wrong with it. She laughed bitter and short. You’re the only one who thinks so. I doubt that, but I’m not interested in everyone else. For a moment, the air between them was fragile, thick with something unspoken.

“You’re kind,” she whispered. “It’s dangerous being kind.” “Not as dangerous as being cruel,” he replied. Two days passed. Then three. By the fourth, the entire estate was a buzz. Rumors floated like mist. Some said Lord Cashion was hosting a banquet for foreign nobles.

Others whispered that he intended to marry off his youngest daughter next and that Livia had been disposed of to make space for the new match. Livia didn’t care. She helped muk stalls carried pales of water learned how to knead bread and silas never once treated her like she didn’t belong. One afternoon while she was dragging a bucket across the yard, she heard a whistle.

Looks like the pig ass escaped again. a voice jered. Livia froze. Three servant boys leaned by the stables, laughing. She even waddles like one. Before she could turn, Celas was already there. He didn’t shout. He didn’t strike them. He just stared long and hard. Say it again, he said. The boys fell silent. I said, Celas repeated. Say it again.

None of them did. They scattered like leaves in wind. He turned to her slowly. “Don’t listen to them,” he said. But her hands were already trembling. The bucket slipped, splashing water everywhere. As she stepped back, I need a moment. And she ran.

She didn’t stop until she was in the barn, hidden behind the bales, crying silently. Celas found her minutes later but didn’t speak. He simply sat beside her and waited. When the tears slowed, she whispered, “You can’t protect me from all of them.” “No,” he agreed. “But I can protect you from believing them.” That night, he cooked dinner for her.

He hummed again, and this time, she hummed along. By the end of the week, she noticed something new. The way he looked at her when she laughed. The way he always walked on the outside of the path, keeping her closer to the hedges. The way he’d remember how she liked her bread crisped or her tea with honey. And her own heart, how it fluttered now when he spoke.

She had been given to him as punishment, but it no longer felt like punishment. It felt safe, whole. It felt like she was becoming someone she didn’t hate, someone worthy of love, even if she didn’t yet know what that meant. Not truly, but she was going to find out because the world was about to test them both.

And it would begin at dawn when a letter arrived that would shake everything. The letter arrived in a wax sealed envelope the color of blood. A rider came at first light, galloping up the eastern road, his horse foaming at the mouth, breath fogging like smoke in the cold morning air.

Celas had seen messengers before, always stiffbacked, coldeyed men bearing bad news for someone, but this one wasn’t meant for the master of the house. No, this one asked for Celas by name. That alone was enough to turn heads. He met the man just outside the barn. Livia still inside kneading dough with flour up to her elbows. She didn’t hear the sharp exchange of voices, nor did she see the messenger shove the envelope into Celas’s hands and ride off without a backward glance. But she saw his face when he walked back in.

It was pale, blank. “I’ll be gone by noon,” he said simply, setting the letter down like it weighed 1,000b. I need to travel to the mountain provinces. What? Her hands still do forgotten. Why? He hesitated then handed her the letter. She turned it over in her hands then opened it. The handwriting was elegant, sharp to Celas of Orand. Your mother lies dying.

If you wish to see her again, come quickly. You were never truly forgotten. But if you wait too long, all that remains will be regret. Ezra. She read it twice, then a third time, the words blurred. You never told me you had family, she said softly. There wasn’t much to tell, he replied, already gathering his satchel. My father died in the famine, my mother. She must have survived longer than I thought.

Ezra was her brother, my uncle. You haven’t spoken to them in how long? Seven years, he glanced at her. since the day I was sold. The silence stretched. Livia stood frozen, hands still sticky with flower, heart pounding with something she couldn’t name. Fear, loss, or something worse. Something like being left behind before anything had truly begun.

You’re coming back, right? That gave him pause. He looked at her long and searching, then nodded once. Yes. But even as he said it, she saw the uncertainty in his eyes. The rest of that morning passed in silence. Livia helped pack his things. He didn’t have much. A worn book, an extra pair of boots, a carving knife, a wooden comb.

She tucked a small jar of honey into the bag when he wasn’t looking. “I don’t know if they have this where you’re going,” she said, pretending to busy herself with sweeping. He smiled. “Thank you. They walked together to the edge of the estate.

The old road curved down into the valley, and already the sunlight was beginning to burn through the morning mist. He looked taller today somehow. Or maybe it was just that she was seeing him clearly for the first time with the pain, the hope, the weight of memory all etched into his features. “Take this,” she said, pressing something into his palm.

It was a button from the sleeve of her old gown, the same one she wore the night her father cast her out. It wasn’t valuable, but it was hers. “I’ll sew it back on when you return,” she whispered. He closed his fingers around it slowly. Then, without warning, he leaned forward and kissed her forehead, soft, reverent. “I will come back,” he said, “no matter what I find there.

” And then he was gone. Three weeks passed. No letters, no word. Livia tried to keep busy. She cleaned stalls, fed the hens, taught herself to patch the holes in her apron. But every night when she curled up on that little cot by the fire, her hand wandered to the empty space on her sleeve where the button used to be. It was during the fourth week that everything changed.

She had just finished feeding the lambs when two men arrived on horseback. They wore the green sigil of House Veilmont, her father’s house, and their expressions were grim. “Lady Livia,” one of them said stiffly. “Lord Cashion request your presence at once.” She stared. “No.” The word came out harder than she meant.

“I’m not his daughter anymore.” He made that clear. “You misunderstand,” the second guard said. “He’s dying.” She blinked. What? He was thrown from his horse last week. Internal bleeding. The healers say he won’t live another day. He’s asked for you. Livia stood frozen. She thought she would feel nothing or maybe vindication, but instead her stomach turned to lead because no matter what he’d done, he was her father and he was dying.

The estate was exactly as she remembered, cold, enormous, empty of warmth. But the guards led her through without protest. Servants stared as she passed, some with pity, others with confusion. No one stopped her. She found him in the master chamber. He was pale, propped up by silk pillows, and barely breathing.

When his eyes flickered open and landed on her, they filled with tears. “Livia,” he rasped. You came. She didn’t move closer. Not yet. You summoned me. He winced. I was wrong about everything. She waited. I thought I thought if I punished you, I could fix you. But there was never anything broken was there. Livia’s hands trembled. No, there was. He looked away ashamed. I sent you to that boy as a lesson.

But I see now he was the only one who ever deserved you. Her heart twisted. She stepped forward and sat beside the bed. I forgive you, she whispered. Not for your sake, for mine. His breathing slowed. Tell him thank you, he murmured. Celas’s a nod. Then with a final breath, Lord Cashin closed his eyes. The funeral was grand, lavish, expensive. Livia didn’t cry.

She returned to the barn that night alone again. And when she opened the door, her breath caught in her throat because there he was. Thela’s standing by the fire cloaked in snow. She ran, not delicately, not gracefully. She ran and threw herself into his arms. He caught her and held her. They didn’t speak for a long time. Finally, she pulled back, eyes shining.

“I thought you weren’t coming back.” “I said I would,” he replied. “I keep my promises.” “What happened?” He looked down at her, smile, faint, but real. “My mother passed before I arrived, but I buried her next to the old pine tree. Ezra gave me her journal. She never stopped praying for me. He touched her face, thumb brushing her cheek, and she wrote about you. Livia blanked me.

She dreamed of the girl I’d love someday. Said she’d be brave, kind, strong, and that I’d recognize her by the way she stood up to cruelty without losing her softness. Her eyes filled with tears. “I missed you,” she whispered. “I missed you more.” He took her hand and pulled something from his satchel. The button.

He placed it in her palm. Time to sew it back on. She laughed through her tears. I never stopped hoping. But the world had one more twist in store. That night, a letter arrived. Not from a friend, not from family, but from a noble house two counties over. To Lady Livia of Veilmont. We write to inform you that your late father owed a debt to our family. As his sole heir, you are now responsible.

Payment must be rendered, or we will collect in other ways.” The candle trembled in Livia’s hand as she read the letter a second time, then a third. The words blurred and blurred again until she finally blinked hard, heart thutting so loud she could barely hear Cela’s asking what was wrong. She handed him the paper.

He read it in silence, lips pressed in a tight line, shoulders straightening with each sentence. A debt, she asked. What debt? He never spoke of this. Celas looked up, eyes steady, but his voice was tight. It says your father owed them. That makes it real. Nobles don’t care if you knew or not. All they want is what’s owed or blood in place of it. She sank onto the stool, her legs too weak to stand.

How much do they want? He held the letter toward the candle light again, reading the fine print at the bottom. 2,000 in gold. The number sat between them like a stone dropped into deep water. Livia’s throat went dry. That’s impossible, he finished for her, for most people, especially for us.

Celas folded the letter, calm returning like a mask slipping into place. But Livia saw the storm in his jaw, the set of his shoulders. He wasn’t calm. He was calculating. “Then we run,” she said. “We pack what we need. We go before they arrive.” “But he didn’t move.” “No,” he said, voice lower. Now running makes us pray. They’ll find us eventually, and the farther we run, the worse it’ll be when they do. She stood again, trembling.

Then what do we do? Sila stared at the fire, hands flexing. We buy time. 3 days later, the writers arrived. Two men in black coats, one woman in red. Their horses were fresh, their boots polished, and their eyes lingered on the barn like it was something to be surveyed and filed away, not a place someone might live.

“The woman was the one who approached first.” “I am Lady Kayia Thorne,” she said without smiling. “I represent House Brierhelm, to whom your father owed a significant debt. We’ve come to collect.” Livia stepped forward. Sila stood just behind her, silent but solid as a wall. I received your letter, Livia said. We don’t have that kind of money. Lady Kalia raised a brow.

Then you should begin thinking creatively. Your father gave us collateral before he died. Property mostly, titles. But his final promise was sealed with something more valuable. Livia’s mouth went dry. What do you mean? Kalia’s gaze moved over her slowly, coldly. You sila stepped forward then, fury burning behind his eyes.

She’s not for sale. Lady Kalia’s expression didn’t change. That’s not for you to decide. Legally, she is the last surviving heir, which means the debt is hers. The terms are binding. We’re offering her a choice. Pay, serve, or surrender. Livia’s pulse roared in her ears. Serve it. Kayia’s lips twitched. You’ll live in our estate, attend to duties, cook clean, perhaps host gatherings for a term of 10 years, at which point the debt will be forgiven. Celas barked a hollow laugh.

And how many survive those 10 years? The woman didn’t answer. They were given two days to decide. Just two. Livia didn’t eat that night. She couldn’t. Her hands shook too much. Her thoughts wouldn’t stop circling the same thought her father had sold her once. And now in death he’d done it again.

Only this time there was no noble house behind her name. No wealth, no weight, just herself and the man beside her. Celas paced the barn after midnight, boots scuffing soft across the old planks. He looked toward her bed, watched her curled under the old quilt. He thought she was sleeping. she was.

I can’t let them take you, he said finally, as if she’d asked him something. She opened her eyes. And if I go willingly, he turned to face her. You won’t. You said we couldn’t run. Well find another way. What way? She said, voice rising. We have nothing, Celas. You have a name that used to mean something in the outer provinces.

And I have what? this barn, a dozen hens, an apron full of holes. He crossed the space between them in two strides. You have me. It came out fierce, fiercer than she expected. You have me, Livia, and I’ll stand between you and anyone who tries to take you. She blinked hard, then whispered, even if they kill you for it. He didn’t flinch.

I’d rather die standing than live without you. The next morning, Livia wrote a letter of her own. She folded it with shaking hands and pressed the wax seal down with the back of a spoon. Then she handed it to Celas’s. I want you to take this to the outpost near the trade road, she said. Give it to the courier there.

Tell him it’s for Lady Rosund of Hillville. Silas frowned. Who is she? My aunt. She left court years ago. She wanted nothing to do with my father, but if she’s alive, she might help. He looked down at the letter again. What did you tell her? Livia’s jaw trembled. The truth, all of it. He nodded slowly. I’ll leave tonight.

That night, Sila’s rode beneath a full moon. The road was quiet, dust rising behind his horse in long silver clouds. He reached the outpost before dawn, the courier there promised to deliver the letter within the week. But when Celas’s returned to the barn, Livia was gone.

There was no note, no sign of struggle, just her empty bed, the folded quilt, the soft scent of rosemary on the pillow. Cela stood in the doorway, heart turning to stone. He checked the ground. tracks. A wagon no more than 2 hours old. He mounted again without hesitation, followed the prince east toward the woods, and found them by the stream.

Lady Kalia, her men, and Livia sitting stiff in the back of the carriage, her hands bound at the wrists. She didn’t see him at first, but he saw her, and he drew his axe. They didn’t hear him until he was close, too close. The first guard turned just in time to see the blade coming. Celas didn’t miss. The second reached for his pistol, but Celas was faster.

He tackled him from the side, knocked him cold with a headbutt, and rose bleeding but unbroken. Lady Kalia backed away, horror etched into her perfect features. You fool, she agreed to come. Celas wiped blood from his temple. She didn’t agree to chains. He stepped forward. “You’ll ride back to your master,” he said, voice like gravel.

“And you’ll tell him that the debt died with Lord Cashion. If you try to collect it again, I’ll bury the whole house myself.” Kayia stared at him, then at Livia, then without another word, she turned and fled. Cela’s cut her bindings. Her wrists were bruised. She looked up at him, ashamed. I thought I could end it. I thought if I gave myself up, you’d be safe.

He took her face in both hands. You’re not mine to give away, but I’ll die before I let them take you. She broke then, fell into him, and this time he held her without hesitation. Two days passed, then four, then a week, and just as the worry began to rise again, a letter arrived, this time on parchment soft as velvet, sealed in silver wax.

To Lady Livia of Veilmont, from Lady Rosund of Hillville. Dearest niece, I have waited many years for this day. The moment your father cast you out, I vowed that if ever you called, I would come. My carriage will arrive within the fortnight. Do nothing. Rest. Prepare. You are not alone anymore. And you shall never be again. Livia read it aloud three times.

Then she looked at Cela’s and for the first time in weeks, maybe years, she smiled without fear. But even as hope rose in her chest, she felt a chill down her spine. Because in the shadow of the hills, a figure watched them. And it wasn’t Lady Kalia. It was a man in white. And he was smiling. The man in white leaned on the post fence just beyond the wild grasses, his coat crisp, his boots without a single scuff. He held no weapon, smiled with a serenity that made Celas’s skin crawl.

That was the thing about him. He looked too clean, too untouched, as if dirt dared not clinging to his hem. Livia didn’t see him at first. She was brushing the mayor outside the barn, her letter from Lady Rosamund folded neatly in her apron. She hummed under her breath, soft and strange for her, something gentle born of hope. It had been days since she dared sing anything at all.

When she did finally glance up, her hands froze midstroke. The curric slipped and thudded to the earth. “Seeilas,” she whispered, but it wasn’t loud enough. “The man in white raised one hand slowly, palm out. His smile didn’t reach his eyes. He didn’t blink.” “Afternoon, miss.” Celas stepped from the barn in the same moment, straw clinging to his sleeves. He spotted the man instantly. Livia didn’t need to explain.

Cela’s voice dropped like thunder. Turn around and walk back the way you came. The man did not move. You’re the one who took out Brierhelm’s collectors, he said, voice light pleasant. That took some fire. I’ll admit I’ve seen plenty fold by now. You didn’t.

Cela stepped forward, closing the space between them slowly. His axe was not in his hands, but the way he moved, balanced, grounded, warned of what would follow if pushed. I said, “Walk away.” The man chuckled once slow. “Oh, I’m not with Brierhelm anymore. Not in any official sense, anyway. You might say I handle Overflow. They don’t like to get their hands dirty.” Celaz’s eyes narrowed.

“Then go tell them the debt was a lie, and they’re never getting her.” “Oh, I believe you,” the man said, still smiling. “But I think you misunderstand what this is.” He reached into his coat slowly and pulled out a small black card. On it was a seal Livia didn’t recognize. Two ravens circling an iron gate. He didn’t hand it to her. Just let it catch the wind and drop at her feet.

You were never the debt, Lady Livia, he said softly. You were the wager. Livia’s breath caught. What? Celas moved closer, now nearly face to face with the stranger. She was wagered in a game, he growled. The man’s smile widened. A high one, a desperate one. Lord Cashion lost much in his final years.

Property, power, reputation. But even in his fall, he found clever ways to place one last bet. You. Livia felt her knees tremble, but she didn’t fall. The man bowed mockingly. You’ve become valuable, my lady. Not because of who you are, but because of who wants you now. Celas took a single step forward. The man didn’t flinch.

Tell your master, Celas said, voice low. He can come for her himself. The man grinned wider. He will. Then he turned and walked into the grass, coat fluttering, boots silent. They watched until the white vanished among the yellow stalks. Then neither of them spoke for a long time. That night Livia didn’t sleep.

The barn was warm, the wind soft, but the air in her chest would not calm. She stared at the ceiling as the stars shifted slowly through the gaps in the beams. She’d almost allowed herself to believe it was over, that they had won. But this this was a game her father had started long ago, a game she didn’t understand.

And now she was a piece on some board no one had ever shown her. Sila sat nearby, sharpening his axe. Every scrape against the stone echoed like a heartbeat. Rhythmic, unchanging, comforting in its own way. “Do you think he’ll really come?” she asked softly. “Seeas didn’t pause.” “He’s already here somewhere.

Men like that send others to announce the storm. Then they wait for lightning.” Livia closed her eyes. I’m not worth it. The axe stopped midstroke. She opened her eyes again, sensing the air had shifted. Celas was watching her. Don’t you ever say that again. His voice was firm, quiet, but iron underneath. I’ve seen the world twist men like your father. I’ve seen them treat love like a coin, a daughter like a title deed.

But what they discarded, that’s where God begins his work, not theirs, his tears burned behind her eyes. Then why does it still hurt? He set the axe down, walked over, and knelt beside her bed. Because love costs, he whispered, even when it’s real, maybe especially then.

She turned toward him, tears spilling over. He didn’t kiss her. He just held her hand. And for once she didn’t feel broken, just held. Three days passed without a sign of the man in white or anyone else. And then Lady Rossund arrived. The carriage was not grand, but it was polished, tasteful, elegant in its restraint, pulled by two white horses.

Rosamund herself stepped out not in a gown, but in sturdy riding leathers. Her hair was stre with silver, her back straight as a sword, and her presence filled the barnyard before she said a word. She took one look at Livia, then opened her arms. It was not the hug Livia expected. It was not gentle.

It was fierce, like someone trying to squeeze all the years they’d missed into a single moment. “My poor girl,” Rosamund whispered into her hair. “I’m sorry. I should have come sooner. I should have come when you were born. Livia wept openly in her arms. Sila stood back unsure until Rosamon turned and appraised him. You’re the one who saved her. Sila’s shifted his stance. I just didn’t let them take her.

Rosamon’s eyes softened. That’s more than most men ever do. That evening they dined under the stars. Rosamon spoke of the northern province where she lived, quiet and far from court, a place where the old rules barely reached, a sanctuary. Livia listened with hungry ears, hearts slowly mending with each story, each promise of safety. But she noticed something. Celas wasn’t eating. He was watching the woods.

“Something’s wrong,” he said after the meal low enough only she could hear. “What is it?” He stood slowly, too quiet. Rosamon rose too, instantly alert. And then they heard it. The horses screamed. They ran to the edge of the trees. The carriage was burning. Both horses gone. A body lay crumpled in the dirt.

One of Rosamon’s guards. Livia froze. Celas moved without pause, dragging the guard from the flames, but it was too late. Smoke poured into the night, choking the stars. Rosamon’s face turned to stone. “They waited,” she said breathless. “They were watching us.” Silas turned, blood on his hands. “This was Brierhelm.

This was cleaner, faster.” Rosamund nodded once. “I know who it is.” Livia stepped forward. Who? Rosamund looked her dead in the eye. The house of Holland. The name meant nothing to Livia. But Celas swore under his breath. Rosamund continued, “Your father’s greatest rival. He ruined them at court publicly in a wager over inheritance lines.

He made them beg for mercy. That card, the one with the ravens?” Livia nodded. That’s their mark. They’ve been waiting to make him pay, and now they’ll do it through you. Celaz’s voice was a snarl. Then we kill them first. But Rosamon looked tired suddenly. They don’t play fair, and they don’t play clean. They use men like that one in white. Hunters, strategists.

They’ll wear you down before you ever see their master’s face. Livia looked between them. Then what do we do? Rosamon’s answer was quiet. We make you disappear. The plan was simple. Rosamon would head north as a decoy. Leave obvious trails. Livia and Celas would take a side path through the old river roots.

Long dried but still walkable. No carriage, no horses, just them. The moment they passed the last rise of the hill, they would be ghosts. It nearly worked. But just before nightfall, Livia heard a sound in the rocks ahead. Not wind, not water, a whisper. And when Cela’s turned to check it, the ground gave way beneath them both.

Livia screamed as the earth cracked. Cela’s grabbed her arm, tried to pull her back, but the old trail betrayed them. Sand collapsed in an avalanche and they tumbled into darkness. Rock and dust swallowing them whole. They landed hard. Celas groaned.

Livia lay still and above them a silhouette stood at the edge of the pit. White coat gleaming, smiling down like a fox over a trap. “Well,” the man said calmly, “I do love when they make it interesting.” The light from above was dim, a golden haze through the drifting dust. Livia’s ribs achd with each breath, and somewhere near her right shoulder, something burned sharp and deep. She couldn’t move.

Sila’s groaned beside her, half buried beneath crumbled stones and brittle branches. He shoved debris off his chest and reached for her immediately, crawling toward her even before he checked his own injuries. “Livia,” he gasped. are you? I can’t move, she said, voice tight. He pressed a palm to her shoulder, gently wincing as she flinched.

You’re hurt, but not broken. That’s good. That’s Thank God. High above, the man in white stood unmoving at the lip of the ravine, hands clasped behind his back. “Don’t worry,” he called, voice echoing too clear. “It’s not deep enough to kill. That wouldn’t be much of an ending, would it?” Sila stood, rage rising in his chest like smoke through dry kindling.

I’ll climb up there, he shouted, and I’ll show you what an ending looks like. The man only smiled wider. I know you will. That’s why I brought company. He stepped aside. Two more men appeared at the edge, rough, muscled, dressed in black. Not Brierhelm’s thugs. These were trained, calculating.

One of them held a rifle. The other held a lantern, lowering it slowly into the ravine by a rope. “We won’t shoot,” the man in white said sweetly. “Not yet. The Hollands have no interest in blood. Not if you return the wager willingly. You’ve proven your medal truly, but the girl belongs to them now.” Celaz’s grip clenched. “She doesn’t belong to anyone.” Above them, the man in white shrugged.

“Suit yourself.” He turned and vanished from the ledge, his echo trailing after him like a ghost. The two blackclad men remained, watching, waiting. Cela’s turned back to Livia. Her face was pale, but her eyes were clear. “We need to move,” she said through gritted teeth.

“I can carry you,” he answered, already kneeling beside her. “No,” she caught his sleeve. “They want us to rush. That’s their mistake. We wait until they lose patience. Celas looked back at the top. The men hadn’t moved. He nodded slowly. All right, then. We wait. Night fell. The stars came out. Still the men above didn’t leave. But neither did they act.

Livia rested against a slab of broken rock. The pain dulled slightly by the herbs Celas had crushed between stones and pressed into her shoulder. He sat beside her, silent, knife in hand, cutting notches into the wall. “What are you doing?” she asked. “Counting?” he muttered.

“Days?” “No reasons,” she turned to him, confused. “Reasons for what?” “He didn’t meet her eyes. to stay alive. Livia was silent for a moment, then. How many so far? She’s glanced at the wall. 22. She swallowed. And me? He hesitated. You’re at least 15 of them. They didn’t speak again for a while. By morning, the watchers were gone. But they’d left something behind. A rope ladder.

dangling halfway into the ravine. It was a trap, obvious, but it was also a chance. Silas tested it carefully. It held. “I’ll climb first,” he told her. “Then pull you up after. No mistakes.” She nodded. But as his boots reached the halfway point, Livia heard something new. “Movement. Not above. Below.

” She turned and saw the figures emerging from the shadows. Three of them, not soldiers, women, dirty, ragged, thin as bone, and trembling like leaves in wind. They stared at Livia as if seeing a ghost. Then one of them whispered, “You’re the one.” Livia backed against the wall, “What?” Another woman stepped closer, her hair shorn unevenly, face stre with soot. Your Lord Cashin’s daughter, the one they all wanted, the one they couldn’t sell.

Celas froze halfway up the ladder. Livia’s breath caught. How do you know that? The woman looked up at her, eyes glassy with tears. Because we were the ones they sold instead. The old cavern stretched far beyond the pit, deeper than either of them had guessed. Beneath the ravine lay tunnels, ancient, forgotten, used once for mining and now for darker trades.

The women led them through these slowly, their lanterns flickering against stone walls carved by hands long dead. There were others down here, a dozen at least, all women, all silent, until Livia arrived. Then they began to speak, not to her, about her. She was the one her father refused to show. She was the wager they promised to the winner.

She was the prize. Livia sank to her knees. “No,” she whispered. “I didn’t know. I swear I didn’t. We believe you, the first woman said softly. You were just a piece to them like the rest of us. Sila stood nearby, fists clenched. How long have you been here? The woman didn’t answer. She only raised one arm and showed the brand on her wrist. A circle of ravens.

The House of Holland keeps their promises, she said bitterly. even the cruel ones. Sila stayed near Livia that night. The caverns were cold but dry, safe in a way the outside world hadn’t been in days. Livia lay awake, listening to the breathing of the others, wondering how many of them had been children when they were taken, wondering how many were still waiting to be saved.

Celas touched her shoulder gently. She winced. Sorry, he murmured. I’m all right. No, you’re not. They looked at each other in the dark. He hesitated, then asked, “If I asked you to come north with me after this is over, would you?” Her breath caught. “Why?” “Because I don’t want you to disappear,” he said quietly.

“I want you to live.” She zurged his vase. Do you mean that? I mean every word. And then he did something. he hadn’t dared before. He reached up, touched her cheek, and kissed her, not roughly, not like a man claiming a prize, but like someone grateful to have found something he never thought he’d deserve. When they parted, her tears were silent, and he held her until morning.

At dawn, the women gathered. They were ready not just to escape, but to fight. They had been broken, but now they had a leader, Livia. They watched her as she stood beside Cela’s, arms still in a sling, hair braided down her back by one of the girls who had whispered prayers into her shoulder through the night. “I can’t promise we’ll win,” she told them.

“But I swear I will never let them take another one of us again. The women raised their fists, even those who could barely walk, and they followed her. The escape began in the tunnels. Sila scouted ahead. Livia stayed in the center, but they didn’t get far. The tunnel forked near the exit, and standing in the narrow passage was the man in white.

alone, unarmed, smiling, touching, he said, voice echoing. But you should have taken the ladder. Livia stepped forward. You use women like dice in your games. You destroy them for sport. The man blinked slowly. No, I don’t destroy them. He stepped closer. I collect them.

And from the shadows behind him, more men appeared. 10, 12, maybe more. All dressed the same, all expressionless, weapons drawn. Livia turned to Cela’s. He drew his axe, and without another word, he charged. The crash of metal against bone echoed like a thunderclap. Celas met the first man with the full weight of his shoulder and ax, cleaving the narrow tunnel into chaos. He didn’t wait for orders or signals. He fought like a storm breaking loose.

Every motion born of rage, purpose, and years of grief stacked in silence. Behind him, the line of women huddled, but they did not cower. Livia stood among them, barely steady on her feet, her right arm still bound, her breath shallow. But her eyes stayed fixed on Cela’s. And then she stepped forward. Push, she cried. They’re only men.

Her voice, broken and bruised as it was, rang against the stones like a bell. The women moved not back but forward. Some held sharpened iron bars. Some held rocks. Some held nothing but the memory of their stolen dignity, but together they surged. The first line of guards staggered beneath the weight of fury. One woman leapt at top a man’s back and dug her teeth into his neck.

Another drove a stick into the back of a knee. Blood slicked the stone floor, but no one stopped. Not even Livia. She moved forward through the crush, caught a falling man’s blade before it clattered and swung wide with her uninjured arm. A guard cried out. She did not hesitate. Pain blurred her vision, but she didn’t fall. She couldn’t. Not now. Not when this mattered. Celas grabbed her wrist.

Livia, go back. I won’t. You’ll die then. Let it be for something. The tunnel trembled underfoot. Explosions. No footsteps. From behind. Livia turned. Her stomach dropped. More men. Not guards. Soldiers. House. Holland had sent its private army. They filled the tunnels like locusts. Faceless, armored, and silent. The survivors were trapped.

Celas pushed Livia behind him. There’s too many. The women back together, shields of flesh and bone. They had come so far. And then a tremor, not footsteps. Something deeper. The wall to the left of the soldiers cracked, split, and shattered. Through the dust, a figure emerged, broad hooded, bare-chested, muscled like a horse, and not alone. 510.

Then dozens more appeared, men and women in rough cloth, bearing torches and crude weapons, and they all bore the same mark on their arms, a burned X over a chain. Former slaves, the mines had awakened. The newcomers didn’t pause to explain. They fell upon the soldiers like thunder, breaking their line with sheer weight. The tunnel screamed under the battle.

Livia felt Celas’s grab her hand. Run, he said. They didn’t argue. The deeper caverns opened wide, old train tunnels from when the mine had been alive. Now they ran in darkness, damp with forgotten water and echoing with voices of the dead. Livia clutched Celas’s hand as they led the escape, weaving past rotted beams and collapsing stairwells. Every so often, another girl grabbed her arm and asked what to do.

Livia didn’t know, but she answered anyway. Keep going. Don’t stop. Behind them, the battle roared. The man in white was still alive. Somewhere she felt it. They surfaced just before dawn. The tunnel’s exit broke through the side of a rocky cliff east of the Holland estate. Wind whipped across the plains.

The horizon bled red. They emerged into a different world. Freedom. The survivors, 27 in all, collapsed in the brush. Some wept, some laughed. Cela stood covered in blood, one hand on his knee. Livia sat beside him. They didn’t speak. Not yet. A soft voice broke the silence. Is it over? A girl, 13 at most, hair shorn, arms scarred.

Livia looked at her. No, she whispered, but it’s beginning. They didn’t go far. They set up camp near a stream. Sila said there’d be shade by midday and they’d need water. He built fires, gathered food. Livia tended wounds with what little she remembered from her mother’s nurse.

For two days they hid and healed, but on the third day smoke rose on the horizon. Not fire, dust, writers. Cela saw it first. We don’t have time. He turned to Livia. They’ll come for you again. She shook her head. No. He gripped her shoulder. You don’t understand. You’re not just a daughter anymore. You’re a symbol now. They’ll send more.

They’ll burn this land down to find you. I’m not leaving these girls. They’ll die. Then I’ll die with them. He stared at her. Then took a long breath. Then I guess I stay too. She looked away, blinking hard. Why? He reached out slowly, touched her chin. Because you make me believe again. In what? In love. That night the riders came but they didn’t come as raiders. They came in silence.

Black horses, black clothes, the holland crest on their lapels. The man in white at their head. He didn’t smile now. He stopped his horse 10 paces from the fire light. Daughter of Cashion. He said, you have something that belongs to us. Livia stood slowly. I belong to no one. The man’s lip curled. You were wagered.

I was not asked. He looked to Celas’s. You think she loves you? You’re a slave, a mongrel, a toy she used to find her spine. Silas didn’t blink. I don’t care what you think. I’m not speaking to you. The man’s voice sharpened. I’m speaking to her. He rode closer. I know your father, Olivia. I know what he did. I know how he wept when you refused to marry. How he begged me to fix you.

He didn’t give you to me because he hated you. He gave you to me because he couldn’t bear to look at what he made. Livia’s jaw clenched. Good. Then he doesn’t have to see me now. The man raised his hand. The writers drew pistols. Last chance, he said. Livia stepped forward. Do it. He blinked.

She tore her shaw from her shoulders. Underneath the mark burned across her skin. Scars left by the tunnels, the fire, the lash. You made this, she said. So come finish it. Silence. Then a crack. One of the writers flinched. Not from her, from behind. Then another. The man turned. Figures moved behind the trees.

Dozens, then hundreds, farmers, ranchers, slaves, freed men, all armed, all silent at their center. An old man with a Bible in one hand and a rifle in the other. He raised it, spoke only one line. She is not alone. The Holland writers fled not because they feared a fight, but because for the first time they feared losing it.

They vanished into the night and no one followed. Livia collapsed against Celas’s chest. He held her and whispered, “It’s done.” She looked up, “No.” He blinked. “We haven’t danced yet.” And in the fire light with survivors watching, she leaned forward and kissed him again. They called it the river camp.

A scatter of tents and makeshift cabins now dotted the glade near the stream where Celas and Livia had led the girls after the escape. It wasn’t much, but to those who’d known only chains and windowless walls, it was heaven. And to Livia, it felt more like home than any parlor or hall she’d grown up in. She stirred a pot of beans while three of the younger girls gathered firewood nearby. One of them, quieteyed Bess, had begun laughing again.

Another Sarah could finally look men in the eye without trembling. Some of them still cried at night or flinched at raised voices or clung to each other when shadows grew long, but they were mending slowly together. Livia’s arm was healing. The cuts on her face had scabbed over. But inside, something deeper stirred.

A part of her that once hid behind polished mirrors and corseted pride had unraveled. In its place bloomed something quieter, stronger. She had stopped hating herself. and Silas. He stayed close, not hovering, not pushing, just there, chopping wood, fixing roofs, sitting beside her when she watched the sunset.

He’d lost so much, but he never complained, even when he coughed blood behind the shed at night, even when his shoulders trembled beneath the weight of all he refused to speak. Livia noticed, but she didn’t press. Not yet. He always returned to her. like the moon to tide. The camp had visitors now. Families from nearby valleys, widows and ranchers, former slaves who brought news of uprisings from the south. People were listening. Some even stayed.

A man with a gray beard who’d lost both sons to Holland soldiers brought them crates of flour. A oneeyed girl arrived with a rifle and asked if she could learn to guard the eastern ridge. They weren’t an army, but they were no longer afraid. Word spread that House Holland had gone quiet.

Some claimed Cashion himself had fallen ill. Others whispered he’d taken his own life. None of it mattered to Livia. Not anymore. One night, under a sky fat with stars, Cela stood by the riverbank, his reflection flickering. Livia found him there barefoot in the grass, a bottle of water in one hand and silence in the other.

Can’t sleep, she asked. He shook his head. I keep hearing them. The girls? No, the ones I couldn’t save from before. She stepped closer. You did save them. I didn’t save you. You did? Celas turned, eyes rimmed in quiet ache. No, you saved yourself. She moved beside him. And you saved me after. He looked down. She touched his chest. I used to think I was cursed, she said.

That I was born wrong. That my size, my face, my softness made me undeserving. You’re not soft, he murmured. She smiled. Yes, I am, but I’m not weak. He took her hand. then dropped the bottle and reached for something in his coat. A necklace, the locket, the same one she’d seen once dangling from a chain around his neck before the first night he held her. He placed it in her palm.

She opened it. Inside a photo creased and faded, a girl smiling. “My sister,” he said before they took her. Livia blinked back tears. She looks like you. She was the only one who called me by my name. Not boy, not mule, just Cela’s. She’d be proud of you. He said nothing then. I don’t know how to do this.

What love? Livia leaned forward. Then we’ll learn together. And she kissed him. This time it was slow, not frantic, not desperate, just safe, full of something old and new all at once. The next day, three girls went missing. At dawn, Sarah came running to the camp barefoot and breathless.

Riders, she panted, took them from the creek, two men in black. Celas’s jaw clenched. Livia stood up. Which way? North toward the mesa. Celas didn’t hesitate. I’ll go. I’m coming too. Livia said. No, you can’t stop me. I’m not trying to stop you. I’m trying to keep you. I’m not something to keep. He met her eyes. And smiled. Then let’s bring them home.

They found the trail by noon. Horse tracks bootprints. One of the girls ribbons caught on a branch. They rode together, silent. The wind stung Livia’s cheeks and her muscles burned from riding, but her eyes never wavered. Every mile was a prayer, every hoof beat a promise. They reached the mesa by dusk.

Smoke rose from a cave at the base. The entrance was guarded. Two men, lean, armed, and dressed in black coats. They bore no crest. mercenaries likely sent to recapture what Holland could no longer control through fear. Silas signaled Livia to stay back. She didn’t. Instead, she circled wide, quiet as dusk.

By the time he charged the front, she was already behind them. One of the guards fell fast, Celas’s fist breaking his jaw clean. The second turned, and Livia swung the rock she’d found. He crumpled together. They entered the cave. The girls were inside, tied but unharmed. They wept when they saw her. Livia ran forward, untying knots with shaking fingers.

One whispered, “I knew you’d come.” Livia held her tight. “We always will.” They didn’t return to River Camp that night. They stopped in a clearing, made a fire, and sat together. Cela’s, Livia, and the girls beneath the stars. “Why do they still want us?” Sarah asked. Cela stared into the flames.

“Because they built their world on our backs, and they know what happens when we stop kneeling.” Livia looked at the sky. “We’ll keep going.” Cuz nodded. “But we need to think bigger.” The next morning, Livia stood on a hilltop as the camp stirred awake below. Celas came to stand beside her. We have land. We have people, but we need a future. She glanced at him.

You thinking what I’m thinking? He smirked. Probably not. She turned fully. A school? He blinked. What for girls? For anyone. teach them to read, to ride, to speak without fear. He watched her. You’re not who you were. She shook her head. No, and I’m never going back. He reached into his pocket. Pulled out something small. A ring.

Not gold, not silver, just leather, woundtight around a stone. I wanted to give you this the day we escaped, he said. But I was afraid. She smiled. I’m not. And he slid it onto her finger. The chapel was half finished by the time the first snowfall came. The girls helped paint.

The younger one sang, and Livia stood before the fireplace, chalk in hand, writing the motto she’d chosen. Love not owned. Celas’s passed behind her, holding nails in his teeth. She paused. What? He chuckled. You spelled loved wrong. She gasped. He grinned. She tackled him into the hay. That winter, House Holland collapsed. Cashion disappeared. His estates were seized.

And the new governor, a black man from the southern provinces, wrote a letter to Livby personally. It said only, “Let me know what you need.” By spring, the school had 20 children. By summer, they were building a second chapel. And every night, Celas and Livia walked by the river, fingers laced, no longer ashamed, no longer hiding. One evening, Bess approached with a question. “Are you married?” she asked.

Celas’s glanced at Livia. She raised a brow. Well, he turned to Bess. I suppose not yet. The girl frowned. Why not? Livia knelt. Because love isn’t about a dress or a ring. It’s about staying even when it’s hard. And we’ve done that. Best grinned. Then you’re already married. And she skipped off. Celas looked down.

You think that’s true? Livia nodded. Feels like it. He kissed her forehead. Then let’s keep it that way. The sun dipped low behind the cottonwoods, casting gold over the chapel’s whitewashed walls. Livia stood in the doorway, apron dusted with flower, hands resting on her full belly.

The girls had been squealing all morning, half over her cooking, half because she and Celas had finally made it official, with vows spoken not before judges or nobles, but in the presence of the very children they once saved. Celas emerged from the barn, wiping sweat from his brow, his shirt loose at the collar, the same leather ring still snug around his finger. When he saw her standing there, a smile pulled slow and easy across his face like sunlight easing over land once scorched. “You all right?” he asked.

She nodded, brushing hair from her eyes. “She kicked again.” He walked up, laid a hand gently on her stomach. “She’s strong like her father.” He chuckled low and warm. “No, like her mother.” They stood that way as the wind rustled the chapel bell. In the fields beyond, girls chased fireflies, their laughter dancing through the air.

In the schoolhouse, chalkboards waited. On the hill, rows of vegetables sprouted from once barren dirt. All of it born from broken beginnings. Livia leaned into him. I used to think no one would ever see me. Not really. That I was too big, too strange, too much. Sila’s kissed her temple. You were never too much. The world was too small. She closed her eyes.

Thank you for choosing me. He held her tighter. Thank you for saving me. Behind them, the door creaked open and Sarah called. Supper’s ready. Livia smiled. Come on, husband. Sila’s grinned. And together, hand in hand, they stepped into the home they’d built. Not from stone or status, but from something far stronger. Love. The end.