What happens when those trained to heal become casualties of war themselves? Spring 1945. Somewhere along the collapsing Western Front in Germany, the Third Reich’s final days were written not just in military defeat, but in the faces of exhausted medical personnel who had witnessed horrors beyond imagination.

Among the masses of retreating German forces were women in blood stained Red Cross uniforms. Nurses who had worked without rest, without adequate supplies, and without hope. When they finally encountered American troops, their words shocked even battleh hardened GIS. Please end our suffering. Not a plea for mercy, not a cry for help, but something far more heartbreaking.

A request born from months of starvation, exhaustion, and witnessing death on an industrial scale. What the American soldiers did next would challenge everything these German nurses had been told about their enemy. This is their story. By April 1945, the Vermacht was disintegrating across every front.

But behind the retreating combat units came something often forgotten by history. the massive medical infrastructure that had sustained Germany’s war machine for six brutal years. German military medical services, once considered among the most advanced in Europe, were collapsing under impossible strain. Field hospitals designed to treat hundreds now held thousands.

Medical trains that should have evacuated wounded to rear areas sat abandoned on bombed out rail lines. and the nurses many recruited from civilian hospitals or trained through the NS Fraenhaft, the Nazi Women’s League, found themselves trapped in a nightmare of their own. These weren’t hardened SS fanatics or devoted party members.

Most were young women, many barely 20 years old, who had answered a call to serve their nation’s wounded. They came from Munich and Hamburg, from small Bavarian villages and Prussian towns. Some had dreamed of peacetime nursing careers. Others had been pressured by local authorities to volunteer. Now in April 1945, they marched westward in groups of 30, 50, sometimes 100.

Their white uniforms, once pristine symbols of medical neutrality were now gray with dirt, spotted with old blood that wouldn’t wash out. Their red cross armbands were faded, barely visible. The strategic situation was catastrophic. American forces under General Eisenhower were driving deep into Germany from the west.

British and Canadian units pushed from the north. Soviet armies crushed German resistance in the east. The Reich was being torn apart from every direction. And caught in this maelstrom were Germany’s medical units ordered to retreat, to regroup, to somehow continue treating the endless stream of wounded pouring back from a front that no longer existed as a coherent line.

The nurse’s ordeal had begun weeks earlier as American armored divisions broke through German defenses in the Ruer Valley and swept eastward. Oberfeld Dadston Greater Hoffman, a senior medical officer with Ha Sanitates Dean Unit 247 recorded in her journal March 28th received orders to evacuate the field hospital at Fulder.

370 wounded, 12 trucks, half with no fuel, six nurses too ill to walk. What followed was a forced march that would last nearly 3 weeks. The nurses carried what they could. Rolled bandages stuffed in coat pockets. Precious vials of morphine hidden in their uniforms. Surgical instruments wrapped in whatever cloth they could find. But it was never enough.

Every few kilometers, they encountered more wounded German soldiers abandoned by retreating units lying in ditches or farmhouses begging for help. Nurse Anna Kle, just 22 years old, later testified, “We couldn’t turn away. Even though we had nothing to give them, we stopped. We cleaned wounds with water from streams.

We shared our bread until there was none left. We watched men die who could have been saved if we’d had even basic supplies. By April 10th, Hoffman’s unit had dwindled. Some nurses had been separated during Allied air attacks. Others had collapsed from exhaustion and been left behind with local families. The remaining 43 women continued westward following country roads to avoid the main highways now controlled by American armor.

The weather turned savage. Cold April rains turned roads to mud. The nurses marched in worn out boots, many with cardboard stuffed inside to cover holes in the soles. Their feet bled, blisters formed, burst, became infected. Still, they walked because stopping meant capture or death. Food became an obsession. The nurses hadn’t eaten a proper meal in 8 days.

They survived on whatever they could scavenge. Raw turnips from fields, wormy apples from abandoned orchards, once a dead horse they found by the roadside. Its meat carved away by desperate soldiers before them. Nurse Elizabeth Schneider remembered, “Our stomach stopped hurting after the fifth day. That was worse.

It meant our bodies were shutting down. Some of the younger girls couldn’t think straight anymore. They talked about food constantly. Their mothers cooking Christmas dinners from before the war. It was torture. By April the 18th, they heard American artillery in the distance. The distinctive crump crumpc crump of one fi a howitzers different from German guns.

The sound grew closer each day. On the 19th, they passed through a town obliterated by Allied bombing. Not a single building stood intact. In the ruins, they found a makeshift German aid station. Five wounded soldiers and one medic, out of morphine, out of bandages, out of hope. The medic, an older man named Klouse, told them, “The Americans are maybe 10 km west, maybe less.

They’re moving fast. If you keep going this way, you’ll run right into them.” Hoffman faced an impossible decision. Turn east back toward the Soviet advance, head north where British forces were reported, or continue west toward the Americans. She chose west. The Americans, she told her nurses, might at least follow the Geneva Convention.

None of them knew what to expect. Nazi propaganda had spent years painting the Allies as ruthless, particularly toward women. Some nurses had heard rumors of mass arrests of German medical personnel being executed as war criminals. Others whispered about concentration camps, though none could have known then that the Americans had just liberated Bukinvald 10 days earlier.

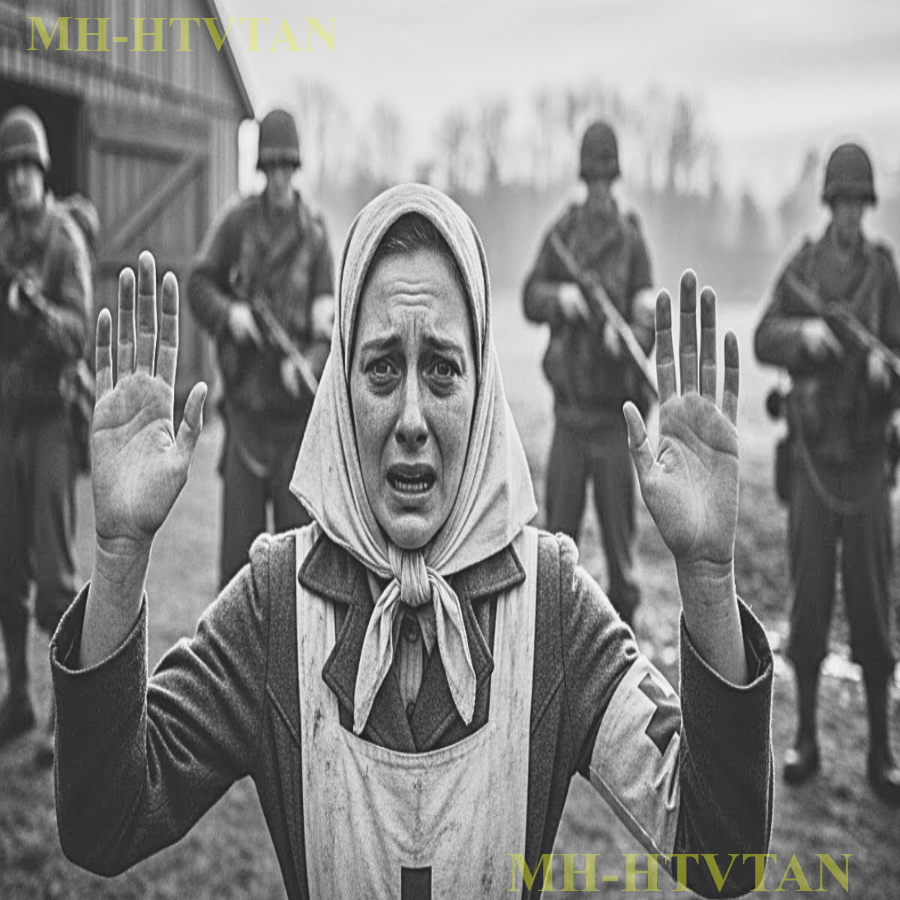

Their fury at what they’d found still raw. On April 20th, Adolf Hitler’s 56th birthday, though none of the nurses cared anymore, they encountered their first American patrol. It happened at dawn near a village called Eisenac, 17 km southwest of Bad Herszfeld. The 43 nurses had spent the night in a barn. They hadn’t slept, hadn’t dared to.

Through cracks in the walls, they watched American vehicles pass on the road. Jeeps, trucks, Sherman tanks, their white stars clearly visible even in darkness. As pink light spread across the sky, they heard engines stop, voices speaking English, boots on gravel. Nurse Hoffman stood first. “Stay here,” she told the others. “I’ll speak to them.

” But when she pushed open the barn door, she found 20 American soldiers already surrounding the building, rifles raised. For a long moment, nobody moved. Then Hoffman raised her hands slowly and in broken English said, “We are nurses, Red Cross. We surrender.” The American sergeant, a man named Thomas Martinez from the First Infantry Division, 16th Infantry Regiment, later wrote in a letter home.

At first, I thought they were soldiers trying to trick us, but then I saw their faces. I’ve seen a lot in this war, but I’d never seen people look that broken. The other nurses emerged from the barn, hands raised. Some were crying, others stared at the ground, unable to meet the Americans eyes. Several trembled visibly from fear, from exhaustion, from starvation.

That’s when one of the younger nurses, barely 19 years old, spoke. Her voice was hoarse, barely above a whisper. Please end our suffering. The American soldiers didn’t understand at first, but the girl’s meaning was clear in her expression. She wasn’t asking for mercy. She was asking for it to be over. The hunger, the fear, the endless march.

She had reached a point beyond hope. Another nurse collapsed to her knees, repeating in German, “Bitter, bitter. Please.” Sergeant Martinez lowered his rifle. He turned to his medic, Corporal James Wright. “Jesus Christ, Jim, look at them.” Wright moved forward slowly, his hands visible, his Red Cross armband prominent on his sleeve.

He approached the nearest nurse, Elizabeth Schneider, and asked quietly, “Are you wounded? Does anyone need help?” Schneider stared at him, uncomprehending. This wasn’t what she’d expected. No shouting, no threats, just concern. Can you walk? Wright asked again, speaking slowly. One by one, the American soldiers lowered their weapons.

What they’d found wasn’t an enemy. It was a group of starving women who had simply run out of strength. Martinez radioed back to his company headquarters. We’ve got 40 plus German medical personnel, female. They’re in bad shape. Request immediate medical evacuation. But the nurses didn’t understand what was happening. Years of propaganda had taught them that capture meant punishment, humiliation, possibly worse.

Some of the women clung to each other, certain they were about to be separated and interrogated. Instead, an American soldier offered one of them his canteen. “Water,” he said simply, pantoiming drinking. The nurse hesitated, looked to Hoffman, who nodded. She drank and the water, clean, cold, plentiful, made her cry. Within minutes, more American vehicles arrived.

A medical jeep pulled up and an army doctor, Captain Robert Sullivan, jumped out. He took one look at the nurses and immediately began issuing orders. Get these women to the aid station now and somebody find them food. Nothing heavy. Their stomachs won’t handle it. Soup, bread, water.

As the nurses were loaded into trucks, many couldn’t process what was happening. They’d braced for anger, for punishment, for the consequences of their nation’s actions. Instead, they found soldiers asking if they needed blankets if anyone had injuries that needed immediate attention. One nurse whispered to Hoffman, “Why are they being kind to us?” Hoffman had no answer.

The American Forward Aid Station was located in a commandeered German school building 3 km west. When the trucks arrived, medical personnel were already preparing to receive the nurses. What happened next would stay with these women for the rest of their lives. Captain Sullivan had ordered his staff to prepare hot stew.

Nothing fancy, just beef, potatoes, and carrots in a thin broth. Proper military rations. But to women who had survived on raw turnips and dirty water, it was a feast. The nurses were brought inside, assigned to classrooms that had been converted to treatment areas, clean beds with actual mattresses, blankets, and in the corner of each room, tables stacked with medical supplies these women hadn’t seen in months.

Fresh bandages, sterile instruments, bottles of penicellin, morphine, cyretes still in their packaging, surgical gloves, antiseptic, everything organized, labeled abundant. Nurse Kle stood frozen in the doorway, staring. She later wrote, “I thought I was hallucinating. For months, we’d been reusing bandages, boiling instruments in dirty water, rationing morphine by the drop.

And here, here was more medical equipment than our entire field hospital had possessed at the start of the war. An American nurse, Lieutenant Mary O’ Connor, approached her gently. “You can sit down. You’re safe now.” “Safe?” Kle whispered in German. “The word felt foreign.” In another room, nurses were being examined by American doctors.

Most were severely malnourished, their weight dangerously low. Many had untreated infections from those bleeding feet. Several showed signs of severe exhaustion bordering on collapse. One doctor checked Schneider’s pulse and blood pressure, then shook his head grimly, “How long since you’ve eaten?” Through a German-speaking American translator, a Jewish refugee from Berlin who had fled in 1938 and joined the US Army, Schneijder answered, “8 days, maybe nine, I’m not sure anymore.

” Then came the moment that broke the last of their resistance. American soldiers brought in pots of hot stew and loaves of bread. Real bread freshly baked by a mobile field kitchen. The smell alone made several nurses start crying. But when the food was placed before them, many wouldn’t touch it.

We We can’t, one nurse stammered. We’re prisoners. We don’t deserve. You’re hungry, Corporal Wright interrupted. That’s all that matters. Eat. Still, several nurses hesitated, conditioned by months of propaganda and fear. Some tried to hide pieces of bread in their pockets or under their cotss, certain this was all they’d receive.

Lieutenant O’Conor noticed and knelt beside one of them. You don’t need to hide the food, she said through the translator. There’s more. As much as you need that sentence, there’s more. Shattered something inside these women. Nurse after nurse broke down. Some sobbed while eating their first real meal in over a week. Others ate mechanically, tears streaming down their faces, unable to process the combination of relief, guilt, and sheer disbelief.

One older nurse, a woman named Margaret, who had worked in a Munich hospital before the war, looked at Captain Sullivan, and asked through the translator, “Why are you treating us like this? We’re the enemy.” Sullivan paused, considering his answer carefully. You’re nurses, he finally said, you took care of wounded soldiers. That’s not a crime.

That’s what medical personnel do. But we’re German, Margaret insisted. And your human beings, Sullivan replied. That comes first. Over the following 3 days, the 43 nurses remained at the American Aid Station, receiving medical treatment and regaining their strength. The transformation was remarkable. Their faces filled out.

The hollow look in their eyes gradually faded. They slept, truly slept, for the first time in weeks, without fear of air raids or sudden orders to evacuate. American medics were surprised to discover how skilled many of these nurses were. Despite the horrific conditions they’d worked under, they knew their craft. Some had performed emergency surgeries under artillery fire.

Others had improvised treatments when supplies ran out. In return, the German nurses were stunned by the sheer abundance of American military medicine. One nurse watching an American doctor casually discard a used syringe rather than boiling it for reuse, gasped. You throw them away after one use. We have more,” the doctor shrugged.

“We had nothing,” she whispered. “How did we ever think we could win this war?” On April 26th, the nurses were transferred to a larger P processing center at Bad Niheim. But unlike combat prisoners, they weren’t held under harsh condition. They were housed in a former German military hospital, given access to proper sanitation, regular meals, and medical care.

Interviews were conducted, not interrogations, but administrative processing. Where were you from? What unit did you serve with? Did you witness any war crimes? Most of the nurses were released within 6 weeks classified as non-combatant medical personnel. They were given papers, travel permits, and directions to refugee processing centers where they could begin searching for surviving family members.

Uberfeld Hoffman returned to her home in Stoutgart to find her neighborhood destroyed by Allied bombing. Her parents had died in 1944. Her brother, a Vermachar soldier, was missing on the Eastern Front. Nurse Kle went back to Keel and eventually resumed her nursing career working in civilian hospitals for the next 40 years.

In a 1982 interview, she reflected, “Those American soldiers saved my life, not just physically, but they reminded me that humanity could still exist even in war.” I’d almost forgotten that. Nurse Schneijder immigrated to the United States in 1953, married a former American GI she met through a refugee aid program, and lived in Pennsylvania until her death in 1998.

She kept a small American flag on her mantle, a quiet tribute to the soldiers who showed her mercy when she expected none. Not all the stories had happy endings. Several nurses never recovered from what they’d witnessed. Some struggled with what we now call PTSD. Others couldn’t reconcile their service to a regime they’d come to understand as evil.

But in that barn near Isizenac on that cold April morning in 1945, 43 women learned something that propaganda had tried to erase. That even in humanity’s darkest moments, compassion could still exist. The American soldiers who found them, men like Sergeant Martinez and Corporal Wright, never considered what they did as heroic. They were simply doing what they’d been trained to do, treat all wounded and sick, regardless of uniform.

But to those German nurses, starving and terrified and certain they’d reached their end, that simple act of human kindness changed everything. Years later, Margaret, the older nurse from Munich, wrote a letter to the First Infantry Division’s Veterans Association. You gave us food when we were hungry.

You gave us water when we were thirsty. You treated us like human beings when we’d forgotten we still were. For that, I will be grateful until my last breath. The Geneva Convention mandates that medical personnel must be treated humanely. But what happened that April morning went beyond legal obligations.

It was a choice, a decision by tired American soldiers to see suffering human beings rather than enemy combatants. In the vast narrative of World War II, this story is barely a footnote. No medals were awarded for it. No official commendations were issued. It was simply one moment of decency in a war defined by atrocity. But for 43 German nurses who’d begged for their suffering to end, it was everything.