January 3rd, 1943, 22,000 ft above Rabal Harbor, the B7 Flying Fortress shuddered as Japanese Zero Fighters tore through her aluminum skin like paper. Captain J. Zemer felt the control stick go slack in his hands. The instrument panel exploded in a shower of sparks and glass. Blood ran down his face, warm against the frozen cockpit air.

The number two engine erupted in flames. Then number three, black smoke poured into the cockpit, choking acrid, carrying the smell of burning rubber and melted wiring. Zeamer’s co-pilot slumped forward, unconscious. His flight suit soaked crimson. Through the windscreen, Zemer watched the ocean spinning closer, a blue green disc expanding beneath them.

He counted 17 separate wounds in his own body. The aircraft was dying. His crew was dying. And in that moment, as his vision began to tunnel and darken, Jay Zemer made a decision that would defy every law of physics, medicine, and probability. He refused to die. The Pacific War was a different kind of hell.

While Europe saw armies clash across fields and forests, the Pacific stretched across 7 million square miles of ocean, distances that made survival nearly impossible. A downed pilot in the English Channel might be rescued within hours. A downed pilot in the Pacific could drift for weeks, watching the horizon for help that would never come.

The B17 crews knew this. Every mission was a calculated risk measured in fuel range, fighter escorts, and the cold mathematics of distance over water. Jay Zmer understood these numbers better than most. Born in 1918 in Carile, Pennsylvania, he’d washed out of MIT’s engineering program before finding his calling in the Army Airore.

But Zemer carried a reputation. Other pilots called him reckless. Commanders called him insubordinate. He’d been transferred six times in 2 years. Always for the same reason, he volunteered for missions no sane pilot would accept. Reconnaissance flights deep into Japanese- held territory. photo runs over heavily defended harbors.

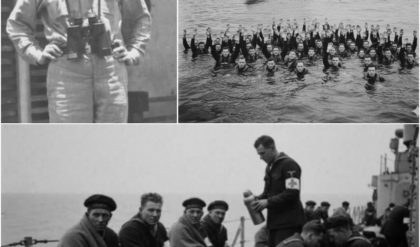

The kind of assignments where aircraft didn’t return. By January 1943, Zemer had assembled a crew as misfit as himself. They called themselves the eager Beaver Z1 men who’d been rejected, reassigned, or written off by the regular bomb groups. Joseph Cernowski, the Bombardier, had been deemed too old at 29. Ruby Johnston, the navigator, wore glasses thick as bottle bottoms.

Bud ths, the flight engineer, had failed his physical twice. Together, they’d scred a warweary B17E that other crews refused to fly. They named her old 666 after her tail number. The aircraft had been shot up so many times, her aluminum skin looked like Swiss cheese. Maintenance crews joked that she stayed in the air through stubbornness alone.

Zemer loved her. He spent weeks modifying old 666, installing extra machine guns in positions where regulations said guns couldn’t go. He added twin 50s in the nose, a pair of 30s in the waist. By the time he finished, the aircraft bristled with 19 guns more firepower than any B7 in the Pacific.

The modifications made her heavier, slower, harder to control. But Zemer had learned a fundamental truth about survival over the Solomon Islands. When you flew alone without fighter escort into airspace thick with Japanese zeros, only one thing mattered. You had to be able to shoot back. The mission brief came down on January 2nd, Bing Island.

The Japanese were building an airfield there, carving a runway out of the jungle to extend their defensive perimeter. Allied command needed photographs, detailed reconnaissance images of the construction, the defenses, the gun imp placements. Five aircraft had already attempted the run. None had returned. The intelligence value was critical.

The survival odds were catastrophic. Speemer volunteered before the briefing officer finished speaking. They took off at dawn on January 3rd. Old 666, heavy with fuel and ammunition. The flight north passed in tense silence. Below them, the Solomon Sea stretched endless and empty. A blue void broken only by occasional cloud shadows.

At 20,000 ft, the crew went on oxygen. The temperature dropped to 20 below zero. Ice crystals formed on the windscreen, delicate and deadly. Navigator Johnston called out way points voice calm despite knowing they were flying toward the most heavily defended target in the South Pacific. The Japanese had stationed over 40 zero fighters at Bingville, another 30 at nearby Bua.

Intelligence estimated at least 70 aircraft within intercept range. Standard doctrine called for fighter escort and a formation of at least six bombers. Zemer had one aircraft and no escort. The math was simple and brutal. Old 666 would have to photograph the entire island, maintain steady altitude and speed for the camera runs, okay, and survive whatever the Japanese threw at them.

Alone, they reached Bingville at 0820 hours. Bombardier Cernowski leaned over his Nordon bomb site, calling corrections as Zemer lined up the photo run. The island appeared peaceful from 22,000 ft green jungle, white beaches, the half-finish runway like a scar through the trees. Then the radio crackled. Boogies 11:00 high. Count 17. No, 20.

They’re everywhere. The Zeros came in waves, diving from the sun, their guns winking orange fire. The sound was catastrophic, a roar that drowned thought that turned the aircraft into a drum beaten by hammers. Bullet holes stitched across the wings, the plexiglass nose shattered. Cerninoski kept calling photo corrections, even as 20 mm cannon shells exploded around him.

Zemer held the aircraft steady, level, giving the cameras time to capture every detail of the airfield below. 20 seconds, 30. An eternity measured in heartbeats and tracer rounds. Then the first engine died. Number two, quit with a grinding shriek. The propeller windmilling uselessly. Zemer fought the controls as old 666 yacht hard to the left.

He trimmed the rudder, compensated with throttle, kept her level. The cameras kept clicking. Through the intercom came the staccato bark of machine guns. His crew fighting back, burning through ammunition at a rate that would empty the reserves in minutes. But the zeros kept coming.

They’d never seen a bomber this heavily armed. They’d never encountered a crew that refused to break formation and run. Cernowski took the first hit. A 20 mm shell exploded in the nose. Shrapnel tearing through his abdomen, nearly severing his arm. He slumped over the bombsite unconscious. Ruby Johnston, the navigator, pulled him back, applying pressure to wounds that wouldn’t stop bleeding.

Cernoski opened his eyes, pushed Johnston away, crawled back to his gun, and kept firing. His blood pulled on the nose deck, freezing in the altitude’s bitter cold. The second engine died. Then the oxygen system failed. Zemer felt his lungs burning, his vision narrowing to a gray tunnel. He nosed old 666 into a shallow dive, trading altitude for speed, descending toward thicker air.

The Zeros followed, sensing victory, moving in for the kill. At 15,000 ft, Zemer leveled off. His co-pilot, Lieutenant Britain, was unconscious, bleeding from multiple wounds. The flight engineer reported fires in the Bombay. The radio operator was dead, and still the Zeros came. A cannon shell punched through the windscreen, exploding between the pilot seats.

Shrapnel tore into Zemer’s legs, his arms, his chest. He counted the impacts five, six, seven separate wounds. Blood soaked his flight suit. His hands slipped on the controls. Through the shattered windscreen, he saw a zero positioning for a head-on attack. Its guns lined up perfectly with the cockpit. Zemer couldn’t move fast enough, couldn’t maneuver, could only watch as the Japanese pilot opened fire.

The rounds walked across old 666’s nose, chewing through aluminum, severing control cables. One bullet entered Zemer’s left side just below the ribs. Another shattered his right arm. Kay felt his body shutting down. Systems failing like the aircraft around him. Aane was distant now, replaced by a spreading numbness.

He knew what that meant. Shock, blood loss, the beginning of the end. The B7 wallowed, barely controllable. Her two remaining engines screaming below them. The ocean waited, empty, infinite, 700 miles from the nearest Allied base. The mathematics were clear. Old 666 couldn’t maintain altitude on two engines. The fuel wouldn’t last.

The crew couldn’t bail out. They were too low, too far from land, too badly wounded. Zemer did the calculation in his head, his engineer’s mind still working even as his body failed. They had perhaps 10 minutes before the aircraft fell from the sky. 10 minutes to make peace with death. But Cernoski hadn’t quit.

Bleeding out on the nose, nearly unconscious. He was still firing his guns, still tracking targets, still protecting the aircraft. Zemer could hear him over the intercom, his voice weak but steady. I got one. Another one breaking right. Engaging. The man was dying and he was giving target corrections. In that moment, Zemer understood.

Survival wasn’t about mathematics, was about refusing to accept the inevitable. Was about holding the controls when every nerve screamed to let go. He pushed the throttles forward, coaxing more speed from the two remaining engines. The aircraft shuddered, threatening to tear apart. Oil streamed from number one engine, coating the wing in black film.

Number four was overheating. The cylinder head temperature climbing into the red. Zemer didn’t care. He aimed old 666’s nose at the horizon and held it there. 700 m. They would fly every inch or they would fall into the sea trying. The Zeros made one final pass. By then, old 666 had descended to 8,000 ft, low enough that the Japanese fighters had to worry about their own fuel.

They came in from a stern, guns blazing, determined to finish the kill. Okay. Zimmer’s gunners met them with everything left in the ammunition boxes. The B7 shook with the recoil of 19 machine guns firing simultaneously. Tracers filled the air. cues. One zero exploded, cartwheeling into the sea. Another broke off trailing smoke.

And then, as suddenly as they’d appeared, the Japanese fighters were gone. Fuel exhausted, ammunition spent. Satisfied that the bomber would never make it home. Silence settled over old 666. A silence more terrible than the battle. Now there was only the labored drone of two engines. The whistle of wind through bullet holes, the ragged breathing of wounded men.

Zemer’s co-pilot regained consciousness long enough to see the damage, then passed out again. The navigator reported their position still over open water 500 m from base. The fuel gauges read nearly empty. And in the nose, Joseph Cernowski finally stopped moving. He’d bled out at his gun, having fired his weapon until the moment his heart quit beating.

Zemer flew on. His vision dimmed. His hands barely responded to commands. Blood loss was pulling him toward unconsciousness. And he knew if he closed his eyes, he would never open them again. So he talked to himself, to his crew, to the aircraft. Stay with me. 666. Keep flying, girl. We’re going home. The bomber responded like a living thing.

Her engines rattling but running. Her battered frame holding together through sheer impossibility. At 14:30 hours, the navigator called out a landmark, Guadal Canal. The island appeared on the horizon like a miracle. Green hills emerging from blue ocean. But old 666 was nearly finished. Number one engine seized completely.

The propeller frozen. Number four was burning oil at a catastrophic rate, maybe 10 minutes from failure. The hydraulics were dead. No landing gear. No brakes, no flaps. Zemer would have to bring her in on her belly at whatever speed the dying engines could maintain. He radioed the tower, told them to clear the runway, told them to have ambulances ready. His voice was barely a whisper.

The medics listening on the ground would later say they couldn’t understand how a man that badly wounded was still conscious, still flying, still making rational decisions. Zemer lined up on the runway, fighting controls that barely responded. The aircraft was vibrating so badly that instruments were shaking loose from the panel.

Two miles out, one mile, old 666 dropped like a stone. Zemer pulled back on the yolk with strength he didn’t have. The bomber’s nose lifted, her tail settled, and then she struck the runway in a shower of sparks and grinding metal, sliding forward on her belly, engines tearing loose, wings buckling. She skidded 800 ft before finally lurching to a stop.

Medics raced toward the wreckage. Firefighters sprayed foam on the burning engines and from the cockpit, barely conscious, bleeding from 17 different wounds, Jay Zemer released the controls and let himself fall. They carried him out on a stretcher. The doctors who examined him couldn’t believe he was alive. 17 wounds, massive blood loss, shrapnel in his lungs, his liver, his intestines.

He should have been dead over Buganville. should have been dead over the ocean. Should have been dead when the aircraft hit the runway. But he’d refused. Simply refused. As if death were a suggestion he could ignore. Five of old 666’s crew were wounded. One had died at his post. They’d brought back the photographs perfect detailed images of the Japanese airfield that would enable the Allied offensive.

More than that, they’d proven something the Japanese hadn’t believed possible. that an American bomber could penetrate their strongest defenses, absorb punishment that should have destroyed it, and return home through sheer determination. Jay Zemer spent 9 months in the hospital, multiple surgeries, infections, complications that nearly killed him twice.

He would walk with a limp for the rest of his life. But he did walk. He did live. And on October 18th, 1943, he stood in a ceremony at the White House as President Roosevelt placed the Medal of Honor around his neck. Joseph Sernowski received the same medal postumously. No B7 crew before or since has earned two medals of honor on a single mission.

The Pacific War would continue for two more years. Old 666 never flew again. her airframe too damaged, her structure too compromised. But her crew’s story spread through the bomber squadrons like wildfire. They talked about the misfit pilot who wouldn’t quit. The bomber deer who fired his guns while bleeding to death. The aircraft that stayed in the air through physics defying damage became a legend that sustained men on other impossible missions.

A reminder that survival wasn’t about the odds. It was about the refusal to surrender. Today, if you visit the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas, you can see Jay Zemer’s Medal of Honor. You can read the mission report, the dry military language that somehow fails to capture what happened that day above the Solomon Sea.

You can see photographs of old 666. Her fuselage so perforated that mechanics counted over 187 bullet holes. You can try to imagine flying that aircraft 700 m, bleeding, dying, refusing to accept the inevitable, but you can’t fully understand it because what Jay Zemer and his crew accomplished exists beyond rational explanation. They flew into airspace where survival was statistically impossible.

They completed their mission while being torn apart by enemy fire. They brought their aircraft home when every system indicated it should have fallen from the sky. They did all this not because they were superhuman, but because they were simply unwilling to quit. The mathematics said they should have died.

The wounds said they should have died. The damage, the distance, the enemy fire, all of it pointed toward the same inevitable conclusion. But mathematics couldn’t account for the human will. For the pilot who kept flying because his crew needed him. For the bombardier who kept shooting because his friends depended on him.

For the navigator, the engineer, the gunners, all of them wounded. All of them terrified. All of them refusing to give up. That’s the real story of old 666. Not the aircraft, not the mission, but the moment when men looked at impossible odds and decided those odds didn’t matter. when they fell from 20,000 ft and simply refused to die.

And that refusal, that stubborn, inexplicable human refusal to accept defeat remains the only force in history that mathematics has never been able to calculate.