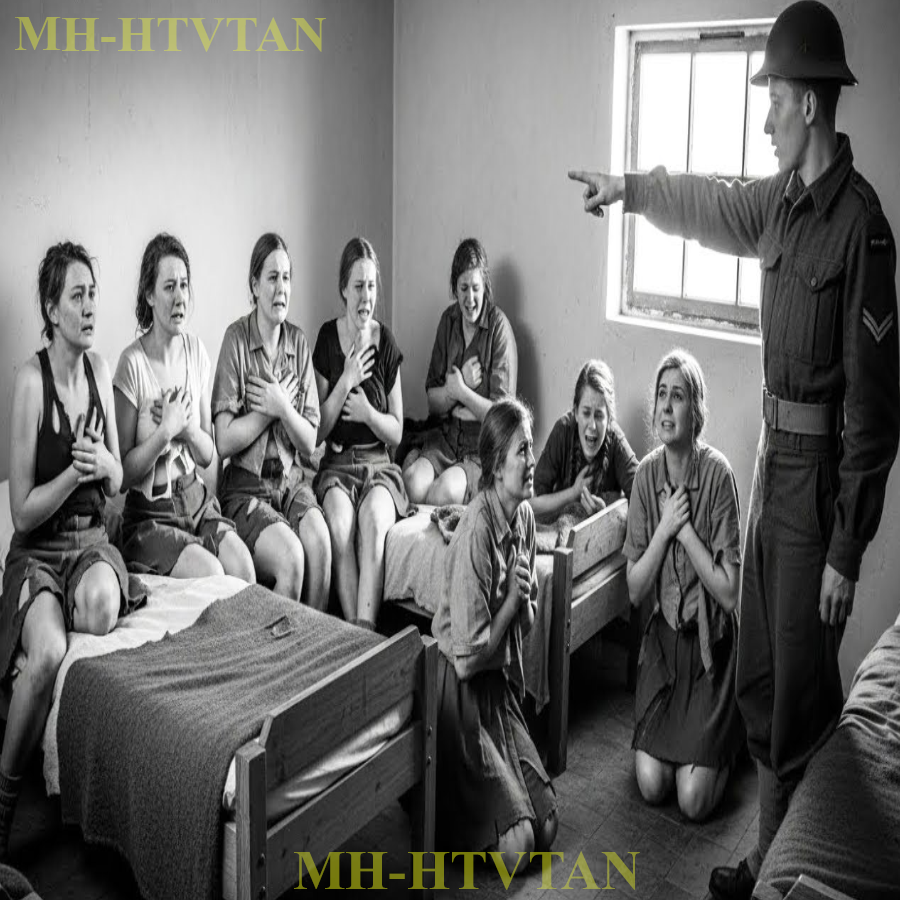

It was 1946, a transit camp in Norfolk, England. The command was simple yet terrifying. Sleep without your clothes. Six words that instantly stopped the breath of 200 German women. The British private, his face impassive under the cold January sun, didn’t need to repeat the instruction. They understood its gravity.

The air was frigid, the temperature hovering near freezing. The wooden barracks rire of stale fear and desperation. Hilda’s heart hammered against her ribs. She was 25, a radio operator captured only a week ago.

Her mind raced, remembering the grim warnings given by their superiors. When the enemy orders something strange at night, it’s never a kindness. But the young British guard, not much older than herself, wasn’t swaggering, and he wasn’t drunk. He was organizing cumbersome metal containers and lengths of pipe.

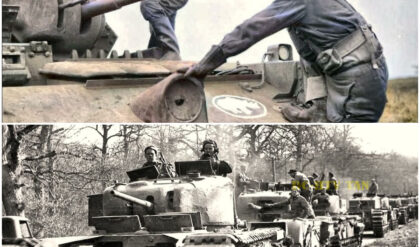

Equipment that looked industrial, systematic, chillingly similar to the descriptions of gas chambers whispered across the Eastern Front. 200 German women, prisoners of war, were housed here, their ages spanning from 18 to 45. Before their capture, 12 had been given small, lethal pills. Two had already used them, preferring a swift exit to the unknown fate awaiting them in enemy hands.

The rest stood in calculating silence, wondering if tonight was the moment they should make their final choice. They will defile us,” whispered Anna, a 20-year-old former auxiliary. Clinging to the grim propaganda films that assured them the British were depraved conquerors. Private Davies, 24, a Londoner, now turned guard, carefully positioned the steam equipment.

More guards arrived, efficiently sealing the windows and installing the machinery outside the main entrance. They didn’t step inside. Why the elaborate setup? Margaret, 33, a skilled interpreter, translated Davey’s clipped words. The procedure begins at 2100 hours and will last for 7 hours. Follow all instructions precisely.

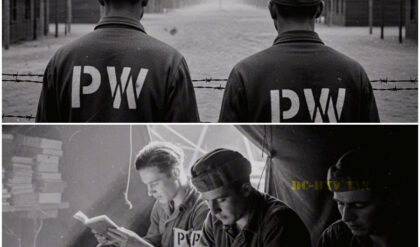

The barracks groaned under the strain of the cold. Each woman stood by her narrow cot. Some were frantically writing final notes. Others discreetly checked the hidden pockets where their unused pills were secured. Their uniforms, worn constantly for months, filthy, torn, and crawling with unnoticed life, were now neatly folded on the floor as commanded.

Hilda, a field medic, felt a cold, calm wash over her. She’d been psychologically prepared for this moment by her old commanding officer. “When they come for you, you know what to do.” The small dark pill remained tucked into the lining of her collar, quick, certain, and an honorable end. Davies checked the pressure gauges on the equipment.

A chemical laden steam began to hiss through the vents. The smell was sharp, acrid, disinfest. The British guards began backing away from the building, pulling on heavy rubber masks. “This is it,” Hilda thought. The guards moved with grim efficiency. No cruel jokes, no shared alcohol, no predatory looks. They were professional, cold, and systematic.

That was somehow infinitely worse than uncontrolled passion, which might end. Systems were relentless. Every woman braced for the inevitable. Die on her feet or submit to the assault. The folded uniforms looked less like clothing and more like white flags of surrender, like shrouds. But Margaret saw a detail that made her pause.

The British guards outside in the bitter cold were stripping too. Their own great coats and battle dress were being thrown into the same metal drums for the same treatment. Why would rapists delouse themselves? The guards finished their preparations and sealed the doors from the outside. The bolts slammed home.

Steam roared through the vents. The 7 hours began. The training echoed in every woman’s mind. The British abused, then they murder always. No exception. Your honor must not survive your body. Choose the pill. But the smell was all wrong. It wasn’t poison gas. It was DDT. Hilda knew that distinctive scent from hastily erected field hospitals on the Eastern Front.

Why were the British sanitizing their enemies? For what purpose? Ruth, 29, a former teacher, secretly clutching the empty space in her collar where her pill had been. The British had found and confiscated all the pills during a thorough intake search, calling them suicide contraband, as if the concept itself was foreign. 73 women were issued pills.

Only two used them. Families had been told their daughters died heroically in combat, never captured. The essential lie required for survival back home. The steam now filled the barracks, bringing with it the first real warmth any of them had felt in weeks, a heavy chemical fog. Through the moisture streaked windows, Margaret saw an impossible sight.

The British guards, shivering in their thin under uniforms in the January air, were tossing their entire kit into the metal drums. Private Davies was operating the equipment, exposed to the elements. Then she saw the evidence that changed everything. Lice, millions of them, dead, falling from the wooden walls, the ceiling, their own threadbear uniforms.

They had lived with the infestation for so long that the constant itching had become normal. The persistent fever a given, the weakness just another symptom of hunger. Anna unconsciously scratched the angry raised welts on her arms. They had blamed the cold, the nerves, the fear. It was parasites feeding, breeding, slowly killing.

They had never provided delousing, never mentioned the infestation, never cared. Through the dense steam, the British guards were now taking the shocking step of burning their own uniforms. Actual flames consuming their clothing. There was no rank, no distinction in the face of this threat. A parasite democracy. Lice did not check passports.

Gizella, 23, a former factory worker, had been delirious for 2 days, blaming hunger and the cold for the spreading rash on her chest. It was the early stage of typhus, an epidemic spreading unseen. The barracks temperature climbed, eventually hitting 35 C. Bodies that had forgotten warmth now remembered.

Muscles relaxing, fear struggling against physical relief. This doesn’t match the propaganda. This doesn’t match the warnings. Why treat enemies as human beings worthy of rescue? Ruth started to strip. Her uniform heavy with six months of wear, never washed, was an insult in hindsight. Pride and endurance masking simple stupidity.

Others followed slowly, their eyes suspicious. But the warmth and the chemicals were killing the true enemy they carried. The British guards were not watching them, not entering, not celebrating. They were freezing outside, destroying their own possessions. Then Margaret saw the full truth. A British medical officer, Dr. Harrington, 42, was holding up magnified photographs to the sealed window.

Lice, typhus bacteria. Death spread by a six-legged vector. The statistics were devastating. Over 90% of the P population was infested. Typhus carried a 20% mortality rate with a 14-day incubation period. By the time the first symptoms appeared, the epidemic was already widespread and unstoppable without immediate action.

We thought it was torture, whispered Hannalor, 27, a surgical nurse, as she pulled hundreds of dead lice from her hair. Each was a vector for disease. They had prioritized ideology and appearance over medicine. Never admitting that German personnel were dying more from lice than from Allied bullets, Harrington’s photographs showed the grim progression.

Fever, telltale rash, delirium, then death. He made sure every woman understood. This wasn’t punishment. It was a desperate act of salvation from a plague they were already carrying. The steam permeated every nook. DDT powder fell like heavy snow. The chemical sting in their nostrils was a minor pain against the realization that it was killing the things that had been silently weakening them, preparing them for the arrival of typhus.

The disinfectant worked systematically. Eggs in the seams, adult insects in the hair, larvi in the fabric. All were dying. The barracks floor turned black with a carpet of dead parasites. Generations of lice, an empire of disease being wiped out. Anna violently vomited, not from the chemicals, but from the realization.

Her weakness, her feverish confusion. It was the beginning of typhus growing stronger every day. The women stripped completely. Shame died in the face of survival. The lice had to die or they would. The equation was simple. Survival mathematics. The British knew this truth. Their own command had ignored it. Hilda’s medical training took over.

She instantly recognized the early symptoms everywhere. Jizzel’s fever, Ruth’s rash, Margaret’s confusion. Early typhus, treatable now, but fatal in a matter of days without intervention. The British guards stayed outside, freezing, burning everything they owned, including their dignity, but saving their enemies from an invisible death, a preventable plague, and the cold neglect of their own military.

7 hours of steam, 7 hours of chemicals, 7 hours of killing what was slowly killing the women. The guards worked through the night, racing the clock against the epidemic. Women unified by the common threat began to help each other. Checking backs, killing manually what the chemicals might miss.

Cooperation born from comprehension. Enemy helping the enemy survive a mutual non-political threat. But when morning finally broke, what they found neatly placed beside their cotss made many of them weep. Fresh uniforms deloused, pressed, and mended. Hilda touched the clean, surprisingly soft cotton. No lice, no blood, no six months of accumulated grime.

Someone had washed, pressed, and cared for the clothing of their enemies. Captain Wilson, 45, a camp administrator, shared the simple, staggering facts. The Geneva Convention, Article 27, mandates the protection of women, P’s dignity. Since the opening of the British camps, zero reported assaults. “We were the savages,” Ruth whispered, holding her freshly cleaned uniform.

The British were following rules that Germany never acknowledged. Rules Germany violated every single day with its own prisoners. Each uniform showed repairs, buttons replaced, tears painstakingly mended, hours of work on enemy clothing by British hands. The cognitive dissonance was shattering. Enemies do not mend enemy clothes, except that they did.

The morning sun streamed through the windows, now cleaned of grime by the steam. The barracks felt transformed, habitable, even dignified. Anna reached into her pocket and found a small crinkly bar of chocolate. A British military ration, 2 ounces of pure sugar and fat. a fortune in a starving Germany. Others checked every woman, every single pocket.

Chocolate purchased from the guard’s personal rations. Some rappers bore the signature of Private Davis, others private Smith. They spent their wages, their own food, on their enemies. The women dressed slowly. The clean fabric felt alien, almost too generous for prisoners, too human for enemies. Some women wept as they put on underwear free of lice, a simple dignity, a forgotten sensation.

Wilson explained through Margaret, “Every prisoner received this treatment, male or female, officer or enlisted. The lice didn’t discriminate. Neither did Typhus. Neither did the British. But the tears flowed for a deeper reason. shame. They had believed the poison of propaganda over the clear evidence of their senses.

They had feared rape more than typhus. They had chosen death over trusting the British. They had almost died from the simple folly of pride. Gizella’s fever broke overnight. The dousing had halted the typhus progression. She would live, saved by the very enemies her own army had left to die from parasites. Ruth began to write frantically documenting the psychological warfare.

How do you process enemies who clean your clothes? Who shares chocolate? Who treats you with a basic humanity that your own command never offered? Who followed the international rules you were taught didn’t exist? The simple, clean, pressed uniform waiting on the cot was more than just fabric.

It was a symbol of restored dignity, of humanity returned, of everything propaganda swore was impossible. That’s when Hilda found something tucked into her uniform pocket that shouldn’t have been there. A chocolate bar with a small handwritten note, stay strong. D. 2 oz of chocolate. A week’s worth of German sugar if you could even find it.

The Allies produced billions of ration bars. billions. The number was incomprehensible to the starving German mind. Private Davies entered with a tray of steaming coffee. Real Brazilian beans, not the burnt grain or acorn substitute they’d subsisted on for years. The steam rose from the metal cups. He served his enemies like guests.

Men like to find humanity from the enemy. This paradox was destroying everything they had believed, everything they had prepared to die to prevent. Davis explained the true emergency. A massive typhus outbreak had struck the main men’s camp. Three dead, dozens critical, spreading exponentially. The women’s camp was the last, the most vulnerable, the most urgent priority.

The British had worked 20 straight hours, barracks to barracks, prisoner to prisoner, racing an epidemic that wasn’t even their fault. German lice on German prisoners. now a British responsibility. The chocolate melted on tongues unused to sweetness. The coffee burned throats unused to heat.

The kindness inflicted more pain than cruelty would have because cruelty merely confirmed the propaganda. Kindness demolished it entirely. Davies confirmed that the chocolate, coffee, soap, and cigarettes were bought with the guard’s personal wages, personal sacrifices for enemies who had expected assault and death, and instead received sugar.

Anna, the 19-year-old who had carried a cyanide capsule, now shared her chocolate with Jisella, still weak but alive, a measurable, irreversible transformation. The crinkling rapper, British milk chocolate, a symbol of industrial abundance, of winning, not just through destruction, but through production. Ruth documented every detail.

The cleaning, the delousing, the chocolate. Evidence that would not be believed back home. Families would not want to hear their enemies were humane. But at this moment, the chocolate dissolved barriers. The coffee bridged the trenches. Humanity transcended the colors of their uniforms. The guards were not monsters.

The women were not just victims. They were human beings sharing sugar and caffeine. Hilda made her decision. She was a trained nurse. The camp had wounded, British wounded, German wounded, and exhausted British nurses. She had the skills. They had the need. The equation was simple. 3 days later, her strength returned.

The lice gone, the typhus prevented, the chocolate, a memory. Hilda made a request that could have easily led to a bullet. Let me help. She pointed toward the medical tents, the chaotic scenes of triage. Major Cooper, 43, saw her medical insignia. He saw his own exhausted staff. He saw the arithmetic. 60 wounded, 12 nurses. Not enough.

He knew from captured files that 47 German PS were trained medical personnel. Hilda, surgical certification. Hannalor, trauma specialist. Ruth, training skills wasted in barracks desperately needed in the tents. Healing knows no flag. Hanalore immediately volunteered. A surgical nurse with three years on the Eastern Front.

She had treated wounded alongside German. Blood teaches equality. 31 women followed within minutes, hands raised. The debt of the chocolate, the gift of the dlousing, the humanity shown. It was time for repayment through service. Through healing. Cooper hesitated. Regulations, security, politics. But the wounded kept arriving. Young British boys bleeding.

German prisoners dying. Mathematics overrode politics. Need transcended nationalism. Within one week, all 47 were working, wearing British uniforms over their own, distinguished only by the international Red Cross armbands. The contradiction was visible. The necessity was obvious. Enemies treating enemies.

Healers healing. Hilda’s first patient was a 19-year-old British private from Yorkshire with a deep infected stomach wound, the kind she had treated hundreds of times. Her hands remembered, scalpel, forceps, sutures. Muscle memory transcended politics. The surgical light burned bright. Antiseptic was sharp in her nose.

Blood was the universal color of urgency. The British boy opened his eyes, saw a German nurse, and whispered a word. Thanks. An effort made. Anna trained as an assistant, too young for full nursing, but old enough to hold instruments, comfort the wounded, and translate pain. German words, British wounds, human suffering. Kooper watched, stunned.

These enemies worked harder than his own allies. Longer shifts, more careful, proving something to the British, to themselves, to the watching world. Healers transcend hatred. Margaret translated technical terms. Morphine dosages, infection protocols. Language barriers dissolved in medical urgency. Pain speaks all languages.

The German nurses worked 16-hour shifts voluntarily, unpaid beyond their rations, but restored to purpose. Not prisoners, not enemies, but nurses, healers, humans with skills saving humans. Ruth treated German prisoners alongside the British. No distinction in care. Blood is blood. Medicine is medicine.

The transformation was complete. Women who expected assault were now saving lives. Guards who could have been abused are now protected. Enemies had become colleagues. But when German officers began to arrive as PWs, the fragile structure was threatened. An officer named Verer saw Hilda treating a British soldier traitor.

The word was a vicious shard of shrapnel. Vera, 38, captured yesterday with 2,000 German officers still wearing the insignia, still clinging to final victory. The medical tent froze. Every German woman stopped. Every British guard tensed. Verer’s authority, even as a prisoner, radiating threat. The conditioning was deep.

Commands, others obey or die. After the war, we will settle accounts. Verer spat on the medical floor where German nurses saved British lives. He vowed retribution for those who chose healing over hatred. But every woman heard the threat. When the British left, when Germany rebuilt, lists would exist. Traitors would be punished.

Colonel Mitchell, 44, intervened immediately, physically stepping between Verer and the nurses. Geneva Convention. Sex separation is mandatory. The male PS were relocated instantly. Hilda never stopped suturing. British blood stopped flowing. German hands healed. The oath she took predated the Reich, predated Verer, predated the war.

Hypocrates over Hitler. Verer’s shouts about racial betrayal and coming punishment faded. But the threat lingered, a poison in the air. 2,000 German officers, zero, were allowed near the hospital. The British enforcement was absolute, protecting the German nurses from the German military. The irony was sharp.

Anna, raised to fear the uniform, now saved the lives of the men Verer wished dead. Mitchell documented everything. Verer’s threats, names, and dates. Evidence for the future trials, for the women’s protection. History inverted. The British military protecting German women from the German military.

The medical tent returned to work, but it was changed. Every woman knew she had chosen a side. Healing over hatred, life over death, future over past. Some would pay for this choice. But tonight, wounds needed cleaning, lives needed saving. The war ended in 4 months. But for these women, the real battle had just begun. May 1945, the war ends.

Repatriation begins. The letters arrive. Their families reject them. Margaret’s husband writes three sentences. You lived. You helped the enemy. Do not return. 20 years of marriage ended in three sentences. The statistics were brutal. 34% of female PS were rejected by their families. Once 200 applied for Allied employment.

400 eventually immigrated to Britain and the Commonwealth. The mathematics of rejection. Better dead than dishonored, Anna’s mother wrote to her 19-year-old daughter, who had saved countless lives. Her family chose ideology over their daughter. Lieutenant Shaw, 30, processed the immigration papers. British hospitals needed nurses.

Sponsors were available. A future was possible for the German outcasts. Britain was taking what Germany discarded. Hilda’s brother declared her officially dead to their neighbors. Easier than explaining her survival. Ruth’s husband had remarried, thinking her dead. She was inconvenient. The rejections piled up daily.

Shaw’s stamps hit the documents, British visas, work permits, new identities. Each stamp rejected the rejection. Each signature was a fresh start. Hannal signed first. Germany offered shame. Britain offered work. Leaving the homeland that didn’t want her for the enemy that did. Anna needed a sponsor.

She was too young to go alone. A Methodist family in Yorkshire who had lost a son in Normandy agreed to take the German girl. Their loss became her grace. Some stayed behind, determined to face the hatred, to rebuild, to show Verer was wrong, to prove that survival wasn’t shameful. The barracks emptied. Women scattered across the globe. 20 years have passed.

Time softened memories. Shame transformed. 1965. Munich. Hilda returned to Germany wearing something utterly unexpected. British Red Cross insignia. She was 44, a British resident and a medical adviser teaching German nurses British techniques. The woman Germany rejected was now rebuilding German healthcare. Davies visited retired civilian clothes, gray hair.

He still brought chocolate, English chocolate bars. 20 years later, the same gesture. Humanity transcending time. Forgive me. Verer spoke from his hospital bed, dying of cancer, begging for mercy from the traitor. 400 former PS became British residents. 89 worked in Commonwealth Hospitals. 12 returned to help rebuild Germany.

The statistics of transformation. Hilda checked Verer’s charts. Professional and thorough. The oath she kept when he demanded betrayal. Verer’s skeletal hand reached out. Desperate ideology was meaningless against cancer. Anna wrote from Yorkshire, “Married, a teacher, three children.” The 19-year-old told to die was now teaching life, sending medical supplies to German orphanages, paying forward the chocolate and kindness.

Margaret was head nurse at this hospital, training younger women, teaching them that survival wasn’t shameful. The hospital ward held former, former, now patients, receiving care from the women they had condemned. Ruth still documented everything for history, for proof that humanity survived its own worst instincts. The stethoscope was cold against Verer’s chest. His heart was failing.

But Hilda held his hand. Traitor comforting. British resident helping German dying. The healer transcends everything. Davies and Hilda drank coffee. Real coffee. Just like 20 years ago. Enemy and prisoner. Then friends now connected by chocolate, by humanity, by choosing healing over hatred. The folded uniform now sits in a museum, a clean, pressed symbol of transformation, of dignity preserved, of enemies becoming human, of propaganda dying while people lived.

Six words terrified them. Sleep without your clothes tonight. What followed? Steam, not assault. Chocolate, not cruelty. Healing, not hatred. Proving that humanity survives, even humanity’s worst demands. If this story moved you, subscribe to the channel. There are many more real accounts like this.

Don’t miss the next one.