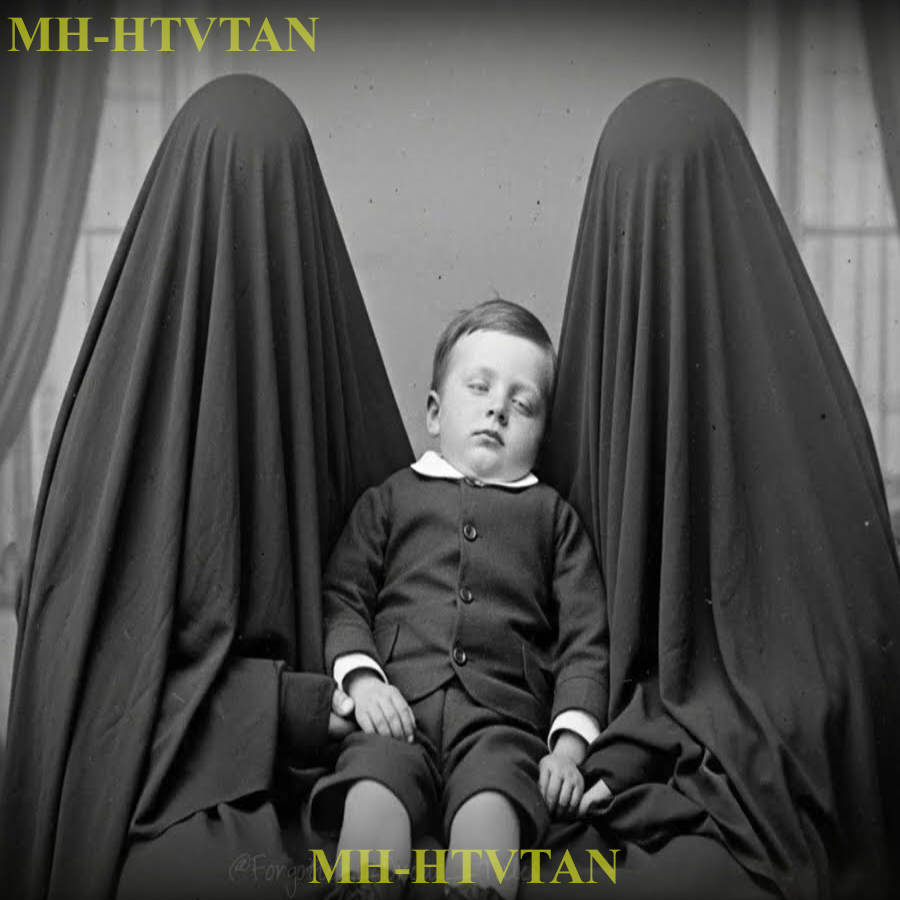

In 1893, another one of those morbid post-mortem photographs so common at the time was taken. A boy, elegantly dressed, seated between two veiled figures. But look more carefully. Notice the details. The hands of the women covered by black veils are positioned identically. The fabrics covering them are different.

One is French silk, the other common cotton. This is the story behind the most controversial photograph ever discovered in Victorian era archives. An image that remained hidden for more than a century and would reveal one of the most disturbing secrets ever kept by an American high society family. The year was 1893. The city of Milbrook in New York State was living its golden days.

Mansions rose majestically along the Hudson River, and among them, none was more imposing than the Witmore residence. Richard Whitmore had built his fortune in railroads, transforming himself into one of the most powerful men on the east coast. His wife, Emma Witmore, was known for her icy beauty and her almost obsessive devotion to the couple’s only son, little Oscar, just 3 years old.

But every fortune has its shadows, and the Witmore was darker than anyone could imagine. Florence Harlow had worked as a seamstress at the Whitmore mansion for 3 years. Young, of humble origins, but of a beauty that did not go unnoticed. She had arrived at the property with excellent references from her former employer in Boston.

What no one knew or pretended not to know was that Florence carried a secret that would forever change the destiny of everyone in that house. The records from that time are fragmented, but through diaries, letters, and court documents, it was possible to reconstruct the events that led to that fateful photograph. It all began in the spring of 1892 when Oscar Witmore became gravely ill.

The best doctors from New York were called, but none could diagnose the mysterious illness consuming the boy. He wasted away with each passing day, and Emma Whitmore grew desperate. It was then that something extraordinary happened. Florence Harlow, the simple seamstress, revealed she had knowledge of folk medicine.

She prepared teas and pices that miraculously seemed to ease the boy’s suffering. Emma, in her gratitude, grew close to Florence in a way that exceeded the relationship between mistress and servant. The two women spent hours together in Oscar’s room, caring for him, watching over his restless sleep. But there was something Emma didn’t know.

Florence wasn’t just a seamstress with knowledge of medicinal herbs. She was in fact Oscar’s biological mother. The story went back 3 years when Richard Witmore on one of his business trips to Boston met a young florist named Florence. The romance was brief but intense. And when Florence discovered she was pregnant, Richard had already returned to New York and his life as a married man.

Desperate and without resources, Florence gave birth to a healthy boy in a charity hospital. What happened next remains shrouded in mystery, but hospital documents indicate the baby was declared dead a few days after birth. Coincidentally, at this same time, Emma Witmore, who had been trying unsuccessfully to get pregnant for years, miraculously appeared with a newborn son.

High society whispered, but Richard Whitmore was too powerful to be questioned. Florence spent years searching for any clue about her son. When she finally discovered the truth, she devised a meticulous plan. She changed her name, created false references, and secured employment precisely in the house where her son lived.

For 3 years, she watched him grow, memorizing every gesture, every smile, every word. It was daily torture, but it was the only way to be near him. Oscar’s illness in 1892 almost destroyed her disguise. Seeing her son at death’s door awakened in her a maternal instinct she could no longer contain. The remedies she prepared were her own mother’s recipes passed down through generations, and they worked because she knew the boy’s constitution better than any doctor. It was her blood after all.

Emma Witmore, in her innocence, never suspected. On the contrary, she developed a genuine affection for Florence, even confessing to her her deepest fears. The two women, united by love for the same boy, created a strange and powerful bond. Florence knew it was wrong that she was living a lie, but she couldn’t walk away.

The summer of 1893 brought a miraculous recovery for Oscar. The boy returned to running through the gardens, laughing, playing. Emma credited the recovery to Florence’s care and insisted she become the boy’s official governness. Richard Whitmore, always absent on his business trips, agreed without question. It was then that fate intervened cruy.

On September 15th, 1893, Oscar was playing near the property’s lake when he slipped and hit his head on a rock. The accident was witnessed by a gardener who ran to help him, but it was too late. The boy died in Emma’s arms, who had run when she heard the screams. The mourning that befell the Witmore mansion was devastating.

Emma entered a catatonic state, refusing to accept her son’s death. Florence, destroyed by grief, almost revealed her secret several times. Richard Whitmore, hastily called from a trip to Chicago, arrived in time for the funeral. It was then that the unthinkable happened. The night before the funeral, Emma sought out Florence in her quarters.

Her mental state was clearly altered by grief. With glazed eyes and a trembling voice, she said something that froze Florence’s blood. I know who you are. I always knew. The confrontation that followed was only partially recorded in a letter Florence wrote but never sent. Discovered decades later among her belongings. In it, Florence describes how Emma revealed she had discovered the truth months earlier through a letter forgotten by Richard on his desk.

But instead of anger, Emma felt a strange gratitude. Florence had saved Oscar, had loved the boy as much as she did. They were in a way both his mothers. Emma then made a disturbing proposal. She wanted one last photograph with Oscar, but not a common photograph. She wanted both of them to be present. The two mothers united one last time before the son they shared.

But there was one condition. Their faces must be covered. We’re not what matters, Emma said. It’s him. It always was him. The photo session took place at dawn on the day of the funeral. The photographer, a discreet man named E. Morrison, known for his work with postmortem portraits, was generously paid not to ask questions.

Oscar was carefully prepared, dressed in his best suit, the same one he wore at Christmas parties. His hands were positioned naturally on his lap, and a slight smile was fixed on his lips through the morttery techniques of the time. Emma and Florence covered themselves with black veils. Emma wore her wedding veil dyed black, made of the finest French silk.

Florence covered herself with a simple cotton veil, the only one she possessed. They sat one on each side of Oscar, their morning hands lightly touching the boy’s shoulders. The exposure lasted an interminable 15 minutes. During that time, neither woman moved or spoke. The only sound in the improvised studio was the ticking of the clock and the muffled breathing under the veils.

When it finally ended, the photographer handed the plate to Emma and left quickly, disturbed by what he had witnessed. Oscar Whitmore’s funeral was an event that shook Milbrook society. Hundreds of people attended to pay their respects. Emma remained strangely serene throughout the entire ceremony, which many attributed to shock.

Florence remained among the servants, crying silently. That same night, Emma sought out Richard in his study. Witnesses reported hearing screams and the sound of objects being broken. The next morning, Richard Whitmore announced that he and Emma would travel immediately to Europe for an indefinite period. The mansion would be closed and all employees dismissed with generous severance packages.

Florence Harlow disappeared that same night. Some say they saw her at the train station. Others swear she was seen entering a carriage bound for an unknown destination. Her room in the mansion was found completely empty except for a single white rose on the bed, the same variety she had cultivated in her flower shop in Boston years before.

The photograph also disappeared. Emma had promised to give Florence a copy, but after the argument with Richard, no one saw it again. It was speculated that Richard, upon discovering the truth about the photo session, had destroyed the image in his fury. The Witors never returned to Milbrook. The mansion remained abandoned for decades, becoming the source of local legends.

In 1920, a fire of unknown origin destroyed much of the mansion. The few objects saved were auctioned off to pay outstanding debts. Among them, there was no photograph. Richard Whitmore died in 1907 in a sanatorium in Switzerland, victim of tertiary syphilis. Emma lived until 1923, spending her last years in a convent in France.

She never spoke again after leaving America, communicating only through written notes. In her room at the convent, the nuns found hundreds of these notes, all containing the same phrase, “I forgive.” As for Florence Harlo, her fate remained a mystery for decades. until in 1952, an elderly woman named Sister Mary Florence died in an orphanage in San Francisco.

Among her few belongings, they found old letters and a diary detailing an extraordinary story. She had dedicated her life to caring for orphan children, trying perhaps to atone for a guilt that was never truly hers. The story could have ended there, another secret buried with its protagonists. But in 1995, something extraordinary happened.

Christy’s auction house in London announced the sale of a collection of Victorian photographs belonging to the estate of an anonymous collector. Among the pieces was an image that immediately caught the attention of specialists. It was the photograph of Oscar with the two veiled women.

The photograph’s provenence was nebulous. The collector had acquired it at a flea market in Paris in the 70s without any documentation, but technical analysis confirmed its authenticity and dating. Even more intriguing were the inscriptions on the back made in two different handwritings. Our angel forever ours. Ew. Forgive me, my love. FH.

The discovery caused a sensation in the world of historical photography. Researchers rushed to investigate the story behind the image. It was then that Florence’s diaries were connected to the photograph and the complete truth finally emerged. But there was still one last mystery. How had the photograph survived and reached Paris? The answer came through a letter discovered in the archives of the convent where Emma spent her last years.

The letter written by a nun named Sister Margarite described how Emma on her deathbed had given her a small package with specific instructions. The package should be sent to an address in San Francisco, the same address as the orphanage where Florence lived under her religious name. Sister Margarite fulfilled Emma’s wish, but the package arrived 3 days after Florence’s death.

The nuns at the orphanage, not knowing what to do with it, stored it with other unclaimed belongings. Decades later, during a cleanup, the package was sold along with other items to a local thrift store. From there, it began its journey around the world until it reached the hands of the French collector.

The photograph was sold at auction to an anonymous buyer for £92,000. Attempts to track down the buyer were fruitless. Some speculate it may be a distant descendant of the Witmores or the Harlows. Others believe the photo returned to the hands of whoever should have always possessed it. The impact of the discovery went beyond the world of collectors.

Historians revised their interpretations of the hidden mother portraits of the Victorian era. Traditionally, it was believed that the veiled figures in these photos were assistants trying to keep children still during the long exposures. Oscar’s photograph suggested a much more complex and emotional reality. Dr. Margaret Thornton, a Victorian photography specialist at Oxford University, published an impactful study on the case.

She argued that many similar portraits could hide equally dramatic stories. The Victorian era was obsessed with death and mourning, she wrote, but also with secrets and appearances. This photograph is a window into a world where love, loss, and deception coexisted in ways we are only beginning to understand. Technical analysis of the photograph revealed even more disturbing details.

Using modern technology, it was possible to examine areas that the naked eye cannot perceive. Under Emma’s veil, it’s possible to discern the outline of a face marked by tears. Florence’s veil shows marks that appear to be blood, possibly from where she bit her lips to contain her sobs during the long exposure. Even more intriguing is Oscar’s position.

While most post-mortem portraits of the era show the dead in rigid and artificial poses, Oscar appears natural, almost alive, his smile, in particular defies the conventions of morttery photography. Specialists debate whether this was the result of exceptional technique by the photographer or if there is something more inexplicable in the image.

Some observers report feeling an unsettling presence when looking at the photograph for too long. There are reports of people who claim to see movement under the veils or perceive subtle changes in Oscar’s expression. Skeptics attribute this to the power of suggestion and the disturbing nature of the image, but the reports persist.

In 2010, a documentary about the photograph was produced by the BBC. During filming, the crew managed to locate distant descendants of both the Whites and the Harlows. Sarah Whitmore Collins, great great granddaughter of one of Richard’s cousins, described how the story had been a family secret for generations.

My great-grandmother used to say there was a curse on the family. She reported that the sin of the fathers had been paid with the blood of the innocent. On the Harlow side, the story was equally somber. Michael Harlow, whose great great-grandfather was Florence’s brother, revealed that the family had changed their name several times over the years, trying to escape the stigma.

Florence was a forbidden name in our family, he said. But my grandmother on her deathbed told me the truth. She said Florence wasn’t a villain, but a victim of her time and circumstances. The documentary also brought to light new documents, including medical records suggesting that Oscar’s death might not have been accidental.

There were inconsistencies in the coroner’s report, and witnesses from that time gave contradictory testimony about the events of that fateful day. Some suggested that Emma, in her fragile mental state, might have had something to do with the accident. Others pointed to Florence, arguing that guilt and despair might have driven her to an unthinkable act.

The truth, as so often happens with the past, remains elusive. What we know for certain is that three lives were destroyed by a tangle of lies, unrequited love, and cruel social conventions. The photograph remains as the only visual testimony of this drama, an image that captures not just three figures, but all the complexity and tragedy of the human condition.

Today, the photograph’s whereabouts are again unknown. The anonymous buyer from 1995 never publicly exhibited it again. There are rumors that it’s in a private collection in Switzerland. Others say it was destroyed for being considered cursed. Reproductions of the image circulate on the internet, but specialists say they don’t capture the true disturbing essence of the original photograph.

What makes this story even more fascinating is how it reflects the obsessions and hypocrisies of the Victorian era. In a time when child deaths were tragically common, post-mortem photography served as a way to preserve the memory of loved ones. But Oscar’s photo transcends this memorial function. It is a document of a divided love, of stolen motherhood, of secrets that destroyed lives.

Contemporary researchers who analyze the case from a psychological perspective suggest the complexity of the emotions involved. Emma, unable to bear a child, accepted another woman’s son as her own. When she discovered the truth instead of anger, she felt an even deeper connection with Florence.

Both had loved Oscar completely. Both had suffered for him. In their shared pain, they found a distorted form of communion. Florence, in turn, lived years of self-imposed torture. Seeing her son daily without being able to acknowledge him, loving him only from a distance, must have been indescribable agony.

Her sacrifice was motivated by love, but the price was her own sanity and identity. Richard Witmore, the great absent one in the photograph, perhaps carries the greatest guilt. His selfishness and cowardice created the situation that led to the tragedy. Documents suggest he knew of Florence’s presence in the house long before Emma discovered it, but chose to ignore it, hoping the problem would resolve itself.

The photograph, in its disturbing beauty, captures an impossible moment. Two mothers, one son, united by death. It is an image that shouldn’t exist that violates all social and moral conventions of the time. But it exists, and in its existence, it forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about love, loss, and the extraordinary lengths the human heart can go to.

Paranormal scholars have their own interpretation of the photograph. They point to the numerous anomalies in the image, shadows that don’t correspond to the lighting, inexplicable reflections in Oscar’s eyes, indistinct shapes in the background that weren’t present in the studio. Some mediums claim the photograph is a portal.

That the souls of the three figures remain trapped in that eternal moment. Whatever the truth, the photograph of Oscar Whitmore and his two veiled mothers remains one of the most enigmatic and disturbing images ever captured. It reminds us that the past is not a safe and orderly place, but a territory full of shadows, secrets, and stories that challenge our understanding.

In an era where millions of photos are taken daily and instantly forgotten, this single image from 1893 continues to haunt, to intrigue, to move. It speaks to us of a time when a photograph was a solemn event. When capturing an image was capturing a piece of the soul. The next time you come across an old photograph in a dusty album or an antique store, stop and observe carefully.

Behind those faces frozen in time, there may be stories as extraordinary as that of Oscar, Emma, and Florence. stories of love and loss, of secrets and sacrifices, waiting only for someone to discover them. And perhaps somewhere in some forgotten attic or private vault, there exist other photographs like this one. Images that capture impossible moments, forbidden emotions, hidden truths.

The Victorian era, with all its obsession with propriety and appearances, was also an era of volcanic passions repressed under layers of social convention. And that’s why this photograph is not just a record of mourning. It’s a mirror, a somber reminder that beneath the appearances of civility and wealth, there have always been hearts in conflict, forbidden loves, and guilt that time could never erase.