Picture this. It’s September 11th, 1985. A quiet 62-year-old man with graying hair and weathered hands walks into the offices of the US Immigration and Naturalization Service in Burbank, California. To anyone watching, he looks like thousands of other senior citizens going about their daily business in Reagan’s America.

But this man carried a secret so extraordinary, so unbelievable that when he finally spoke the truth, it would make headlines across the world and force America to rewrite the final chapter of World War II. His hands trembled, not from age, but from the weight of four decades of deception as he approached the government cler behind the counter.

“My name is Gayorg Gartner,” he said in accented English that had softened over the years. I am a German prisoner of war and I have been hiding in America since 1945. The cler looked up from her paperwork, certain she had misheard. World War II had ended 40 years ago. Every German prisoner had been shipped home decades earlier.

The files were closed. The camps dismantled, the war a fading memory. Yet here stood a man claiming to be the last German soldier on American soil. And what he was about to reveal would prove that truth is indeed stranger than fiction. Stay with me because this story will challenge everything you think you know about courage, identity, and what it truly means to choose your country.

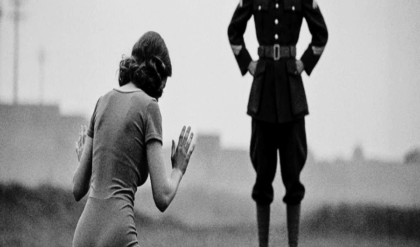

To understand Gayorg Gartner’s incredible decision, we must first travel back to the scorching deserts of North Africa in 1943. The war wasn’t going well for Germany. RML’s Africa Corps, once the pride of the Vermacht, was in full retreat as Allied forces closed in from all sides. Gayog Peter Gadner was just 21 years old, barely more than a boy, when he found himself trapped with his unit near Tunisia.

Like so many young Germans of his generation, he’d been swept into wars machinery before he was old enough to understand its true cost. The propaganda had promised glory and quick victory. Instead, he found himself thousands of miles from home, fighting a losing battle in a desert that felt like the surface of another planet.

The end came suddenly. Allied artillery pounded German positions for hours before British and American forces overwhelmed what remained of their defenses. Gartner, wounded by shrapnel and separated from his unit, crawled behind a destroyed tank and waited for death. Instead, he found capture. British soldiers, their uniforms dusty and faces grim with war’s exhaustion.

Found him semic-conscious among the wreckage. But instead of the bullet he expected, they gave him water. Instead of brutal interrogation, they provided medical care for his wounds. It was Gner’s first glimpse of something that would shape the rest of his extraordinary life. The possibility that enemies could be human.

Like thousands of other German prisoners, Gner was loaded onto ships and transported across the Atlantic to America. The journey took weeks, sailing through yubotinfested waters, past the very submarines that had once been commanded by his countrymen. The irony was not lost on him. America in 1943 was a fortress of democracy.

Its factories humming with wartime production. Its citizens united behind a cause they believed was just. For Gayorg Gertner, sailing into New York Harbor and seeing the Statue of Liberty for the first time, it was like entering another world entirely. Gner’s destination was Camp Demming, New Mexico, one of hundreds of prisoner of war camps scattered across the American landscape.

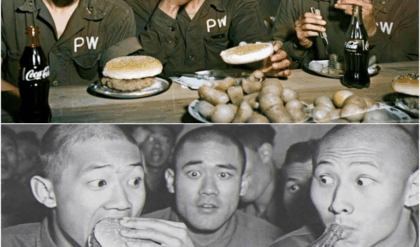

The US military was housing over 400,000 German prisoners by 1943, more than any other nation in history. But these weren’t the concentration camps or gulags that prisoners might have expected. Camp Demming, like most American P facilities, operated under strict adherence to the Geneva Convention. Prisoners received three meals a day, medical care, recreational activities, and work assignments that paid actual wages.

For most of Gertner’s fellow prisoners, the camp represented an unexpected reprieve from the brutality of war. They could play soccer, write letters home, even attend classes taught by American instructors. Some prisoners later said their time in American camps was the best period of their lives. But Gayorg Gertner was different.

While his comrades settled into the rhythm of camp life, Gertner spent his time studying, not English or American history, but escape routes. He watched the guards, memorized their routines, and cataloged every weakness in the camp’s security. The high desert of New Mexico stretched endlessly beyond the barbed wire.

Most prisoners saw only emptiness and death in that landscape. Gner saw possibility. He began preparing with the methodical precision that had made German soldiers famous. He saved scraps of civilian clothing traded from work details outside the camp. He hoarded small amounts of money earned from the camp’s work programs.

$40 that would have to last indefinitely. Most importantly, he studied English with an intensity that surprised his fellow prisoners. Why do you work so hard to learn their language? One prisoner asked him. Gartner’s answer was prophetic. Because I may need to speak it for a very long time. By the summer of 1945, with the war clearly ending and repatriation looming, Gertner knew his time was running out.

He had no desire to return to a Germany that lay in ruins, occupied by foreign armies. The Nazis, who had sent him to war as a teenager, held no claim on his loyalty. America, ironically, had treated him better as a prisoner than Germany had treated him as a citizen. The plan he devised was audacious in its simplicity and terrifying in its complexity.

He would not just escape. He would disappear entirely, transforming himself from Gayorg Gartner, German prisoner, into someone new, someone American. September 10th, 1945. The war in Europe had been over for 4 months. Japan would surrender in just days. Most German prisoners were already being processed for repatriation.

Loaded onto ships that would carry them back to an uncertain future in occupied Germany. Gayorgn knew his turn was coming soon. It was now or never. September 10th was a night like any other at Camp Deming. Guards conducted their routine patrols. Search lights swept the compound and prisoners settled into their barracks for what most assumed would be just another night of captivity.

But Gatner had been planning this moment for months. He had studied the guard rotations so thoroughly he could predict their movements to the minute. He knew exactly where the fence was weakest, where the shadows fell darkest, and when he would have the longest window of opportunity. At 2:17 a.m., when the guard post was between shifts and the search light was focused on the opposite side of the camp, Gatner put his plan into action.

He slipped out of his barracks through a window he had carefully loosened over weeks. Moving like a shadow, he reached the fence where he had been slowly cutting wire strands with a tool fashioned from a spoon handle. The New Mexico desert was brutally cold at night, a shocking contrast to the blazing heat of the day.

Gertner wore every piece of civilian clothing he had managed to acquire, knowing that his prison uniform would mark him as an escapee to anyone who saw him. He crawled through the gap in the fence. For the first time in over 2 years, Gayorg Gertner was free. But freedom in the middle of the New Mexico desert was a relative concept.

He was hundreds of miles from any major city with minimal supplies and a thick German accent that would immediately identify him as foreign. The smart move would have been to head south toward Mexico, where border security was less stringent and a man could disappear more easily. Instead, Gatner did something that would have shocked his captives.

He walked north, deeper into America. The first 24 hours were the most dangerous of his life. When guards discovered his absence during morning roll call, they launched a massive manhunt. Blood hounds tracked his scent for miles. Local sheriff’s departments were alerted. The FBI joined the search.

Radio broadcasts warned civilians to be on the lookout for a dangerous escaped prisoner. But Guatner had vanished into the vastness of the American landscape like smoke in the wind. And what nobody realized was that the escaped prisoner had no intention of leaving the country. In a twist that would have been unthinkable to his pursuers.

Gayorgn was not fleeing America. He was embracing it. Somewhere in Colorado’s mountains, Gayorg Gartner ceased to exist and Dennis F. Wilds was born. Using forged papers created with materials stolen from prison camp and English skills developed through intensive study, Gertner became Dennis Wilds, a drifter from the South whose records were lost in wartime chaos.

His first job, washing dishes in a Denver diner. The owner, who’d lost her son in the Pacific, was impressed by Dennis’s work ethic. Lots of folks from the South talk funny, she told employees. At least this one works hard. Gatner threw himself into becoming Dennis with military precision. He studied American customs through movies, learned accents via radio, absorbed history through newspapers.

But the most remarkable transformation was psychological. As months passed, Gartner found himself genuinely caring about American current events, following baseball scores with real interest, developing political opinions as an American. By 1950, Gayorg Girtner had become Dennis Wilds in ways deeper than false papers. thinking, dreaming, feeling American.

Then something completed his transformation. He fell in love. Her name was Mary, a waitress where Dennis worked as cook. Independent, optimistic, refreshingly direct. They dated from 1951, and for the first time since his escape, Gertner was truly happy. Mary knew Dennis as quiet, and hardworking with a charming accent.

She never questioned his vague background explanations, accepting his reluctance as evidence of a difficult childhood. For three years, Gner experienced American family life. He helped Mary’s daughter with homework, taught her to ride a bicycle, attended parent teacher conferences proudly. They celebrated Thanksgiving, Christmas, 4th of July with genuine enthusiasm.

The relationship ultimately ended over ordinary incompatibilities. Mary wanted marriage and children. Dennis, knowing any official scrutiny could destroy everything, couldn’t commit to marriage’s legal entanglements. When they parted in 1954, Mary said, “You’re a good man, Dennis. I wish you weren’t so afraid of settling down.

If only she’d known what he was really afraid of.” For the next quarter century, Dennis Wilds lived one of the most extraordinary double lives in American history. He worked steadily, moving from job to job and state to state, always careful never to stay in one place long enough to attract unwanted attention, but long enough to establish the references and work history that would support his false identity.

He was a ski instructor in Colorado, charming tourists from around the world with his mysterious European accent and his carefully edited stories of travels that were versions of his real experiences. Wealthy visitors tipped him generously and invited him to parties in their mountain homes, never suspecting they were socializing with a fugitive from one of America’s most intensive manhunts.

He repaired televisions in California during the golden age of that industry. His precise German engineering training serving him well in the emerging world of electronics. Customers praised Dennis Wilds for his meticulous work and honest prices. Some became friends, inviting him to barbecues and family gatherings where he played the role of the friendly bachelor neighbor.

He tended gardens for wealthy families in Nevada, finding peace in nurturing growing things after years of destruction. His employers trusted him with keys to their homes, with their children, with their most valuable possessions. They had no idea they were entrusting their security to a man who was technically still an enemy combatant from a war most people preferred to forget.

Throughout it all, Dennis Wilds was liked and respected by his fellow Americans. He was the kind of neighbor who would lend you tools, help you move furniture, or watch your house while you were on vacation. He paid his taxes faithfully, never missed a day of work unless he was genuinely ill, and had never been arrested for anything more serious than a traffic violation.

But the secret ated him like acid. Every fourth of July felt like a betrayal. But to which country? Every time he pledged allegiance to the American flag, he wondered if he was committing treason. But treason to whom? Germany, which had conscripted him as a teenager to fight a war he never believed in, or America, which had treated him better as a prisoner than his homeland had treated him as a citizen.

The paranoia was constant but manageable. When police officers pulled him over for minor traffic violations, his heart would race, but his carefully maintained papers always passed inspection. The FBI manhunt for Gayorg Gertner had long since gone cold, filed away as just another unsolved case from a war that was rapidly becoming ancient history.

By the 1970s, Gertner had been free longer than he had been a prisoner. America had changed dramatically around him. the civil rights movement, Vietnam, Watergate, the counterculture, and he had experienced it all as an insider, not as a foreign observer. He had watched the moon landing with tears of pride in his eyes.

He had mourned the assassination of President Kennedy as deeply as any American. He had lived through every triumph and tragedy of the American experience for three decades. He was more American than many Americans. The problem was that none of it was legally real. By the early 1980s, Gorg Gardner was entering his 60s. His accent had faded.

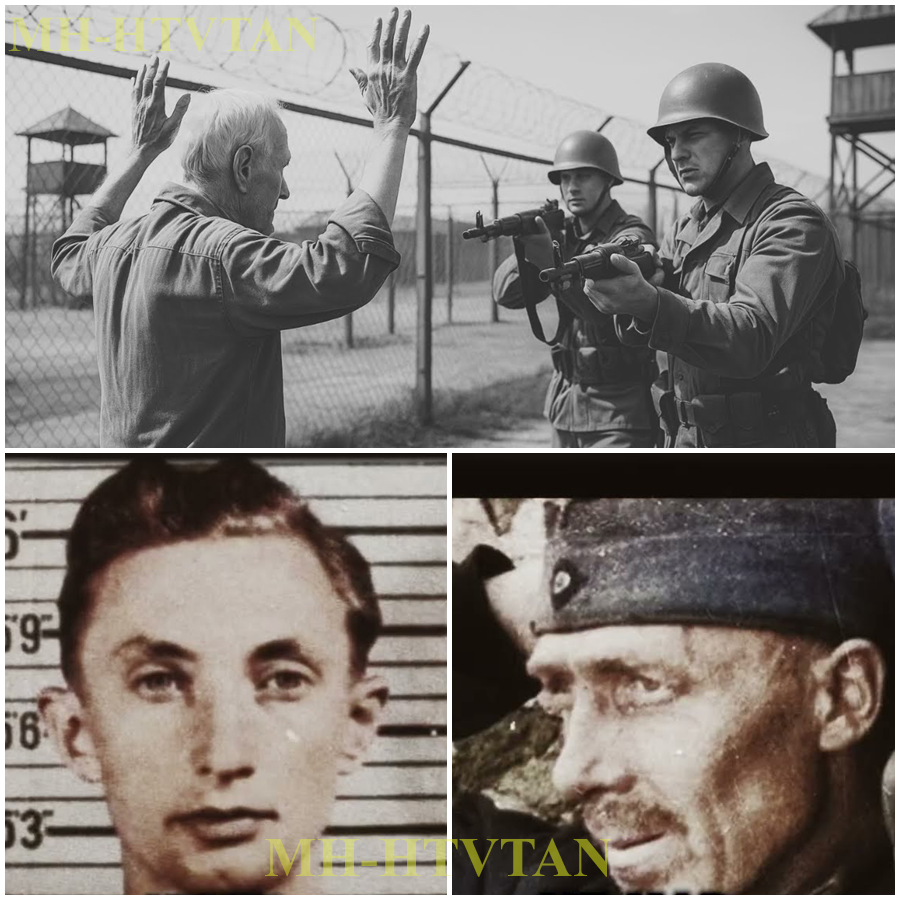

His German grown rusty. Sometimes he struggled remembering German words while English came naturally. In 1983, something sent him into weeks of panic. A magazine article about Wu Ps mentioned, “Gayorg Gartner escaped from Camp Deming, New Mexico in 1945, still at large. Reading his real name in print was like seeing a ghost.

The past he’d worked to escape was still following him. He obsessed over one terrifying question. What would happen if he told the truth? The America of 1985 wasn’t the America of 1945. The Cold War made Soviets the enemy, not Germans. West Germany was a trusted NATO ally. The idea that one elderly man who’d lived peacefully for four decades would be treated as dangerous seemed absurd.

What finally tipped the balance wasn’t fear of discovery, but something profound. The desire to die as himself. At 62, Gayorg Gartner wanted to spend his remaining years as who he really was, not who he’d pretended to be. September 11th, 1985, Gayorg Gartner woke up and made the most incredible decision of his extraordinary life. He was going to surrender.

Not because he’d been discovered, not because he was dying, but because after four decades as Dennis Wilds, he wanted his remaining years as Gayorg Gertner. The walk to the immigration office felt endless. Every step brought back memories. Crawling through the fence, his first American meal as free man. Mary’s laughter, watching the moon landing.

Decades of close calls. At the building entrance, he paused. This was his last chance to turn back, continue the lie that had become his truth. Once he spoke those rehearsed words, there’d be no going back. Gayorgn walked through those doors. My name is Gayorgnner. I am a German prisoner of war, and I have been hiding in America since 1945.

The words hung in the air like a confession that could reshape history. America’s reaction to Gayorg Gertner’s voluntary surrender was unlike anything expected, most of all by Gertner himself. Instead of outrage, the response was overwhelmingly sympathetic. Within hours, the story had leaked to press and by evening Gayorg Gertner was leading every major news network.

But he wasn’t portrayed as a dangerous fugitive, instead as a human interest story. an old man whose incredible journey from enemy soldier to productive American citizen challenged every assumption about loyalty and identity. Editorial writers called him the most honest man in America. Veterans groups expressed admiration for his surrender courage.

Talk shows competed for interviews, treating him more like celebrity than criminal. Federal prosecutors found that while Guyadner had technically committed crimes, escape, immigration violations, identity fraud, he’d committed no crimes during his 40 years of freedom. Given his age, voluntary surrender, and exemplary behavior as Dennis WS, they recommended minimal punishment.

The American public began seeing Gertner not as an enemy combatant who evaded justice, but as an American success story. Here was a man who’d chosen America even when that choice required living as criminal. He’d paid taxes, held jobs, contributed to society for four decades. Letters of support poured in nationwide.

Americans offered jobs, home visits, money. Marriage proposals arrived from women charmed by his romantic transformation story. Gayorgn spent only months in minimum security detention while officials decided what to do with this unprecedented case. He received thousands of supportive letters from Americans. Hollywood producers offered story rights.

Publishers competed for memoirs. Television networks wanted exclusive interviews. But Gner handled fame with quiet dignity, giving few carefully chosen interviews while emphasizing gratitude to America and regret for deception. In early 1986, immigration officials made a surprising decision. Gayorg Girtner was granted permission to remain in the United States as legal resident with a path to full citizenship.

At 63, after 40 years of living as criminal, Gayorg Girtner was finally free, not just from prison bars, but from deception’s prison he’d built around himself. The irony was profound. America’s most wanted escaped prisoner became America’s most celebrated voluntary surrender. After release, Gayorg Girtner lived quietly, working as maintenance man and declining most interviews.

The man who’d lived 40 years under false identity now preferred anonymity under his real name. He never married, never returned to Germany. America had been his home longer than Germany ever was. Gayorg Getner died peacefully in 2013 at age 90 in a California veterans hospital receiving full military honors not as German soldier but as man who served his adopted country through choosing to live productively within it for 60 years.

Gail Gertner’s story challenges every assumption about loyalty, identity, and redemption. He was an enemy soldier who became more American than many Americans. A criminal whose only crime was wanting to be free. His voluntary surrender remains one of the most extraordinary acts of moral courage in American immigration history.

He gave up guaranteed freedom to gain something more valuable, the right to live as his authentic self. Sometimes the most incredible thing a person can do is tell the truth, even when it takes 40 years to find the courage. And sometimes the truth really can set you