What would you do if the only chance to save your family depended on the fragile hands of a child? In March of 1908, on the crowded streets of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a 9-year-old boy carried stacks of newspapers against his chest like they were treasures. But hidden in those same pages was a headline that would seal his fate.

An irony so cruel it remained invisible for nearly a century.

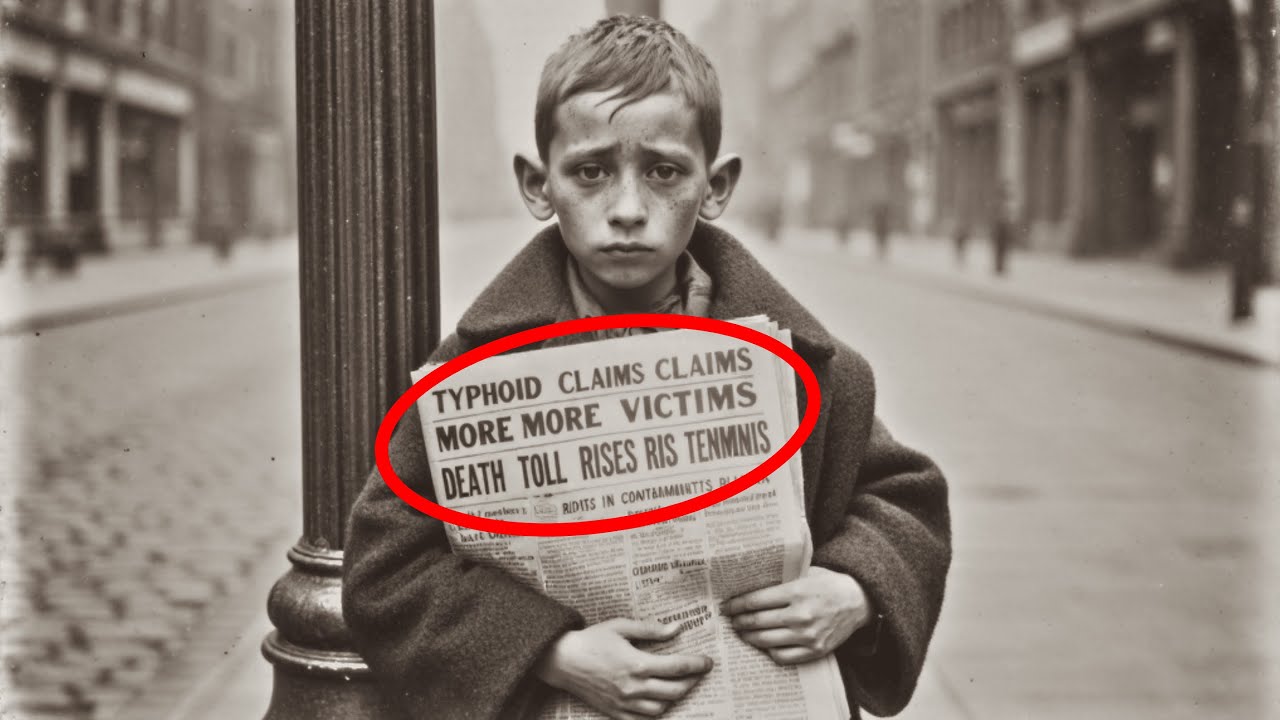

Stories like this remind us why memory matters. Your support helps keep these forgotten voices alive. Look at this photograph. Look closely at the boy holding those newspapers against his thin chest like they were made of gold. March 15th, 1908, corner of Bowie and Delansancy Street, Lower East Side of Manhattan. The photographer who took this image never asked the boy’s name.

Never knew that in exactly 11 days this child would be dead. And if you look carefully at the headline he’s holding, you’ll see the cruel irony that makes this story impossible to forget. Because that headline, the one pressed against his heart, already contained his death sentence.

His name was Tommy Sullivan, 9 years old. And in the next 30 minutes, I’m going to tell you why this photograph should have been evidence in a murder case that was never investigated. This story starts at 4:47 in the morning, 3 weeks before this photo was taken.

Tommy woke up to the sound of his mother coughing blood into a handkerchief she tried to hide under her pillow. The tenement room they shared with two other families was so cold that frost had formed on the inside of the windows. Tommy could see his breath in the air as he pulled on the same clothes he’d worn for the past 6 days. His shoes, when he had them, had holes that led in the slush from the streets.

But that morning, he was barefoot. He’d sold his shoes the week before to buy medicine for his mother. You see, Tommy Sullivan wasn’t supposed to be working at 9 years old. According to the New York State Factory Investigating Commission Records that wouldn’t be created until 1911, children under 14 weren’t legally allowed to work. But hunger doesn’t care about laws.

And when your father died in a construction accident building the Manhattan Bridge, when your mother was dying slowly from consumption, when the rent was 3 weeks overdue, a 9-year-old boy did what he had to do. Every morning, Tommy joined the army of news boys at Park Row, where all the major newspapers had their offices. The New York World, the Herald, the Tribune.

According to circulation records from Pulitzer’s World, newsboys bought papers for two cents and sold them for three. 1 cent profit per paper. On a good day selling 50 papers, Tommy could make 50 cents. Half a dollar to keep two people alive in a city that was eating its young. But here’s what the records from the Children’s Aid Society show that most people don’t know.

In 1908, there were over 10,000 news boys working the streets of Manhattan alone. 10,000 children, some as young as six, competing for the same corners, the same customers, the same chance at survival. And the city didn’t just allow it, the city depended on it. These children were the distribution system for information in the greatest city in America.

The morning of February 22nd changed everything. That’s when the first cases of typhoid fever appeared in the tenementss of the Lower East Side. The Department of Health records preserved today in the municipal archives show that by March 1st, there were already 347 confirmed cases. By March 15th, the day this photograph was taken, that number had risen to 1,47.

The headlines Tommy couldn’t read but shouted every day, were tracking the disease that was already inside his body. Because 3 days before this photo, Tommy had started feeling the fever. His mother noticed him shivering more than usual, but Tommy said it was just the cold. He couldn’t afford to be sick.

Being sick meant not working. Not working meant not eating. And worse, not working meant his mother wouldn’t get the medicine that kept her cough from getting worse. So Tommy did what 10,000 other news boys did every day. He lied. He pretended he was fine. He went to work.

The photographer who took this picture was probably documenting street life for one of the progressive reform magazines that were popular at the time. He saw a typical news boy, a perfect example of child labor in the progressive era. He didn’t see the fever burning at 102° behind those eyes. He didn’t see the boy who hadn’t eaten in two days because every scent went to his mother’s medicine.

He didn’t see that Tommy was holding those papers so tightly because his hands were shaking from chills. But if you know where to look in this photograph, you can see it all. The way he’s leaning slightly against the lamp post, using it to stay upright. The newspapers held high to hide how thin he’d become. And that headline visible if you look closely.

Typhoid outbreak spreads. City health board warns of contaminated water. Tommy couldn’t read those words. He just knew they sold papers. He shouted them over and over, his voice getting weaker each day, never knowing he was announcing his own fate. What happened in the next 11 days would be documented in exactly three places.

A single line in the Belleview Hospital admission records. A note in the diary of a nurse named Katherine O’Brien. And this photograph, which would sit undiscovered in an archive for 93 years, but I’m getting ahead of myself because to understand why Tommy’s death mattered, you need to understand what happened the night before this photo was taken, when Tommy made a decision that would save one life and end his own.

6 months before that photograph was taken, Tommy Sullivan learned the first rule of being a news boy. Territory is everything. The corner of Bowery and Delansancy wasn’t just a street corner. It was survival. And it belonged to Big Mike Brennan, a 15-year-old who ran the news boys in the Lower East Side like a general runs an army

. Until the morning Big Mike found Tommy there at 4:00 a.m., already selling papers to the workers heading to the factories. What Big Mike didn’t know was that Tommy had been sleeping in the alley behind that corner for three nights. His mother’s coughing had gotten so bad that their neighbors in the tenement had threatened to call the health inspectors.

If the inspectors came, they’d see that Margaret Sullivan was dying of consumption. They’d take her to the sanitarium on North Brother Island and everyone knew that nobody came back from North Brother Island. So Tommy made a deal with their landlord, Mr. Kowalsski.

He’d work off the back rent by cleaning the building’s coal furnace every night and running errands during the day. In exchange, Kowalsski wouldn’t report them to the authorities, but the deal meant Tommy had to make more money, which meant he needed a better corner, which meant challenging Big Mike Brennan. The fight lasted exactly 30 seconds. Big Mike knocked Tommy down with one punch, took his papers, and told him never to come back. But something strange happened then.

As Tommy was picking himself up, blood running from his nose onto yesterday’s unsold papers, an older gentleman in a wool coat stopped to watch. This was James Morrison, according to a receipt that would later be found in Tommy’s pocket. Morrison was a clerk at the Immigrant Savings Bank on Chamber Street. Every morning, he bought his paper from whoever was selling at that corner.

Morrison did something that morning that would change everything. He bought all of Tommy’s bloodstained papers, all 50 of them. Then he said something that Tommy would remember until his last day. A boy who gets up after being knocked down is worth investing in.

From that day forward, every Friday, Morrison would buy 10 papers from Tommy and pay for them with a silver dollar. $1 for papers worth 30. It was charity disguised as commerce, the only kind of charity a proud 9-year-old Irish boy could accept. But I need to take you back further to understand who Tommy really was. Immigration records from Ellis Island show that Patrick and Margaret Sullivan arrived from County Cork in 1897.

Patrick found work immediately on the construction of the Manhattan Bridge. According to the bridge company’s accident reports, he fell from a quesanon on November 3rd, 1905. Tommy was 6 years old. The company paid Margaret Sullivan $25 in death benefits. that was supposed to last them the rest of their lives. Margaret tried everything. She took in washing until the lie destroyed her hands.

She swed peacework until her eyes gave out in the dim tenement light. But consumption is a patient killer. It takes its time. By 1907, she couldn’t work anymore. That’s when Tommy stopped going to school. The truency officers came twice. Both times Tommy hid in the coal bin until they left. He couldn’t read or write, but he could count money.

And money was the only education that mattered when your mother was dying. The news boys of 1908 had their own society, their own rules, their own justice. Lewis Hine, the photographer who would later document child labor across America, wrote in his notes that these boys were old men in children’s bodies. They had to be.

The streets of New York didn’t care that you were 9 years old. The other news boys certainly didn’t. There was Joey Matias, a year younger than Tommy, who’d lost three fingers to frostbite the previous winter, but still sold papers with his good hand.

There was Irish Tim, who wasn’t Irish at all, but claimed to be because Irish newsboys sold more papers to Irish customers. There was Silent Sam, who hadn’t spoken since watching his parents die in the tenement fire of 1907. These boys taught Tommy the real curriculum of the streets. How to spot a mark who’d pay extra for a paper. How to make change quickly so customers couldn’t cheat you.

How to shout headlines in a way that sounded urgent even when the news was days old. How to hide your money in different pockets so if you got robbed, you didn’t lose everything. How to stand in just the right spot where the wind from the subway grates would warm you but not blow away your papers. But the most important thing they taught him was about the sickness.

Every news boy knew about the sickness. It came in waves. Chalera in summer, influenza in fall, typhoid in spring, tuberculosis all year round. The Department of Health statistics show that in 1908, one in four children in the Lower East Side died before their 10th birthday. The news boys knew these statistics without knowing the numbers.

They knew because every few weeks another boy would stop showing up at Park Row. By March 1st, the typhoid outbreak had become front page news. The board of health blamed contaminated water from the Croin reservoir. The newspapers blamed the immigrants in their overcrowded tenementss. The rich blamed the poor for living in squalor. But the truth documented in the health inspector reports that wouldn’t be released until 1909 was simpler.

The city had known about the contaminated water for months. They just hadn’t thought it worth fixing until it threatened to spread beyond the slums. Tommy sold those headlines every day. Typhoid crisis worsens. Health board demands action. Death toll rises in tenementss. He memorized the sounds of the words without understanding their meaning. He just knew that fear sold papers.

And in March of 1908, fear was the only thing selling faster than newspapers. But 3 days before the photograph was taken, something happened that changed the mathematics of Tommy’s survival. His mother’s cough had turned into something worse. The blood she’d been hiding was now impossible to conceal. She needed medicine that cost more than Tommy could make in a week.

And that’s when Tommy made a decision that would have consequences he couldn’t imagine. He decided to work through his own fever that had started that morning to push his body beyond what a 9-year-old body could take to sell more papers than he’d ever sold before.

What Tommy didn’t know was that his fever wasn’t from the cold or exhaustion. The typhoid bacteria had been in his system for over a week, picked up from the same contaminated water that was killing dozens across the Lower East Side. Every customer he touched, every coin he handled, every paper he delivered was spreading the disease.

He had become exactly what the headlines warned about, a carrier of the very plague he was announcing to the world. March 12th, 1908, 3 days before the photograph, Tommy woke up at 3:30 a.m. with his undershirt soaked in sweat. The fever had started, but in the darkness of the tenement room, with four other families breathing in the same stale air, Tommy convinced himself it was just the closeness of too many bodies in too small a space.

He had to convince himself because that morning he’d made a promise to Joey Matias, the 8-year-old news boy with the missing fingers, that he’d help him learn the morning roots. You have to understand something about the economics of desperation. Tommy had discovered that if he got to Park Row by 4:00 a.m.

instead of 5:00 a.m., he could buy the previous evening’s leftover editions for half a cent instead of 2 cents. These papers were a day old, but most customers didn’t check the date if you shouted the headlines with enough urgency. On a good morning, he could buy a 100 old papers for 50, sell them for 3 each, and make $2.50 50 cents profit, more money than his father had made in a day building the Manhattan Bridge.

But that morning, standing in line at Park Row, Tommy felt the ground tilt beneath his feet. The fever was climbing. His hands shook as he counted out his 50 cents. Money he’d saved by not eating for 2 days. The circulation manager, a man named Patrick Donnelly, according to the newspaper employment records, noticed Tommy swaying. “You sick, boy?” Donnelly asked. “No, sir,” Tommy lied. “Just cold.

” Donnie had seen too many news boys collapse on the job to be fooled. But he also knew that sending a boy home without papers was a death sentence of a different kind. So, he did what passed for kindness in 1908. He gave Tommy an extra 20 papers for free. “Don’t collapse until you sell them,” he said. Tommy took the papers and headed to his corner. But big Mike Brennan was already there with three other older boys.

The corner of Bowery and Delansancy was prime territory where the workers from the garment factories passed on their way to work. On a normal day, Tommy would have found another corner. But this wasn’t a normal day. His mother needed medicine. Joey needed training. And Tommy needed to sell every one of those 120 papers.

What happened next was witnessed by Mrs. Sarah Goldstein, who ran the kosher bakery on the corner. Years later, she would tell her grandson about the Irish boy who stood up to Big Mike Brennan while burning with fever. Tommy didn’t fight. He didn’t argue. He simply started selling papers right next to Big Mike, matching him shout for shout, headline for headline.

Typhoid spreads through Lower East Side. Mayor promises investigation. Death toll reaches hundreds. Big Mike could have destroyed Tommy. Should have by the laws of the street. But something in the younger boy’s desperation stayed his hand. Maybe it was the way Tommy’s voice cracked on the word death. Maybe it was the fever bright shine in his eyes.

Or maybe Big Mike recognized something he’d seen in too many news boys before. The look of someone selling papers on borrowed time. By noon, Tommy had sold 60 papers. his fever was now 103°, though he had no way of knowing that. He just knew that the street kept swimming in and out of focus, that his throat felt like he’d swallowed broken glass, that every shout for headlines took more effort than the last.

But he kept selling because at 12:30 he had an appointment to keep. Mr. Morrison always bought his afternoon paper at 12:30. He was precise about it, and Tommy had learned to be there at the corner of Chambers and Broadway, papers ready. But that day, Tommy could barely stand. He leaned against the lamp post, the same one that would appear in the photograph 3 days later, and waited.

Morrison appeared exactly on time, but instead of buying his usual paper, he looked at Tommy for a long moment. Then he did something extraordinary. He bought all of Tommy’s remaining papers, 60 papers, and he paid with a $5 gold piece. “You’re sick,” Morrison said. “It wasn’t a question.” “My mother’s sicker,” Tommy replied. Morrison reached into his pocket and pulled out a business card.

“On it was the address of a doctor on Houston Street.” “Dr. Abraham Goldberg,” Morrison said. “Tell him I sent you. He’ll see your mother for free.” Tommy took the card, though he couldn’t read what it said, but he memorized the street name Morrison told him. Houston Street, five blocks from their tenement. Five blocks that might as well have been 5 mi with his fever climbing toward 104.

That afternoon, Tommy did something that would have consequences he couldn’t foresee. Instead of going home, instead of resting, instead of seeing the doctor himself, he took the $5 and went to the pharmacy on Orchard Street. The pharmacist, whose ledger would later show the transaction, sold Tommy a bottle of codine cough syrup for his mother and a small vial of ldnum for the pain. Together, they cost $4.70.

With his remaining 30, Tommy bought something he’d been saving for since December. A pair of children’s shoes from the secondhand store. Not for himself, for Joey Matias, whose remaining toes were turning black from frostbite. The store receipt found years later in the archives of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum shows the purchase.

One pair child’s boots sized small, 30 cents, paid in full. Tommy gave Joey the shoes that evening at the News Boy’s lodging house on Dwayne Street. The Children’s Aid Society ran the lodging house where news boys could get a bed for 6 cents a night and a meal for 4 cents.

Tommy couldn’t afford to stay there, but he knew Joey sometimes slept in the reading room when he had nowhere else to go. Joey tried to refuse the shoes. Pride was sometimes all these boys had left. But Tommy insisted, using logic that made sense only to children who’d learned arithmetic through poverty. You need feet to sell papers.

No feet. No papers. No papers. No money. Take the shoes. That night, Tommy made it home with the medicine for his mother. Margaret Sullivan was too weak to question where her 9-year-old son had gotten such expensive medicine.

She just held him while he shook with fever chills, singing the Irish lullabibis she’d sung when he was small. She didn’t know that her son’s temperature was approaching 105. She didn’t know that typhoid fever had already begun attacking his intestines, causing the internal bleeding that would soon become unstoppable. But Tommy knew something was terribly wrong. In his fever delirium that night, he kept seeing headlines floating in the darkness of their tenement room.

Headlines he couldn’t read but somehow understood. Boy dies selling news of death. Mother’s medicine costs son’s life. Typhoid takes another news boy. March 13th. 2 days before the photograph. Tommy’s fever broke just before dawn, dropping to 101. In typhoid cases, this is called the false recovery. The patient feels suddenly better, even energetic.

It’s the body’s last attempt at normal function before the final collapse. Tommy interpreted it as a sign that he was getting better. He had to get better because he’d promised Joey he’d teach him the roots because his mother needed her medicine. Because Mr. Morrison expected him at 12:30.

That morning, for the first time in his life, Tommy did something he’d never done before. He stole, not money, not food. He stole a newspaper. Specifically, he stole a fresh morning edition and spent an hour in the alley trying to decode the marks on the page. He recognized some letters from the signs around the neighborhood. T for typhoid, D for death, M for mayor.

He couldn’t read the sentences, but he was starting to understand that these marks meant something, that they were more than just sounds to shout. By afternoon, Tommy had sold 90 papers, his best day ever. But the effort had cost him. The fever was climbing again. His vision was blurring, and something worse was happening. He’d started coughing up blood, just like his mother.

But unlike his mother’s consumption blood, which was red and frothy, Tommy’s blood was dark, almost black. A sign that the typhoid had perforated his intestines. Still, he kept selling. Typhoid outbreak worsens. Health board emergency meeting. Contaminated water source found. The irony would have been unbearable if Tommy could have read the words.

The contaminated water source was the public pump on Hester Street, where Tommy filled his cup every morning. where all the news boys gathered before heading to Park Row, where the typhoid bacteria had been multiplying for weeks. That evening, Tommy made it home with another dollar for his mother’s medicine.

But Margaret Sullivan wasn’t fooled by her son’s false energy. She felt his forehead burning again with fever. She saw the dark stains on his shirt where he tried to hide the blood. She knew with the instinct every mother has that her child was dying. March 15th, 1908, 6:47 a.m. The morning of the photograph, Tommy Sullivan stood at the corner of Bowie and Delansancy, holding 150 newspapers against his chest, his body burning with a fever of 105°. He’d been standing there since 4:00 a.m.

when the darkness still held the city, and the only sounds were the milk wagons and the harsh coughs from the tenement windows above. His mother had begged him to stay home. She’d held his burning face in her cold hands and wept.

But Tommy had pulled away with a gentleness that broke her heart and said, “Just one more day, Ma. Mr. Morrison needs his paper.” The truth was simpler and more terrible. They had no food, no coal for heat, and the medicine Tommy had bought 3 days ago was almost gone. One more day of selling papers meant one more day of his mother having what she needed. He didn’t tell her that he’d been coughing up black blood since midnight.

He didn’t tell her that the world kept sliding sideways, that standing required every ounce of will he possessed. He didn’t tell her that he knew, with the strange clarity that comes with fever, that this would be his last day selling papers. At 7:15 a.m., something extraordinary happened.

Big Mike Brennan appeared at the corner not to fight, not to claim territory. He walked up to Tommy, looked at the smaller boy, swaying on his feet, and did something that violated every rule of the news boy hierarchy. He put his hand on Tommy’s shoulder to steady him. “You’re dying, ain’t you?” Big Mike said. Tommy didn’t deny it. Couldn’t.

The blood he just coughed into his sleeve was answer enough. You got family?” Big Mike asked. “My ma,” Tommy whispered. Big Mike nodded. Then he did something that would never be recorded in any official document, but would be remembered by every news boy who witnessed it. He took off his own coat, the thick wool coat that marked him as the king of the Lower East Side news, and wrapped it around Tommy’s shoulders.

“Sell your papers,” Big Mike said. I’ll watch your back. For the next 3 hours, Big Mike Brennan stood guard while Tommy Sullivan, dying on his feet, sold newspapers. Every time Tommy’s voice failed, Big Mike would shout the headlines. Every time Tommy swayed, Big Mike would steady him without making it obvious.

It was the closest thing to kindness the streets could offer, delivered in the only language the streets understood. At 10:30 a.m., the photographer appeared. Nobody knew his name then. The archives would later identify him as Jacob Ree’s assistant, one of the progressive reformers documenting child labor in New York.

He was looking for the perfect image to accompany an article about news boys. What he found was Tommy Sullivan standing against a lamp post holding his papers high. Big Mike’s coat making him look almost respectable despite the fever bright eyes and the trembling hands. Hold still, boy. the photographer said, “Let me get your picture.

” Tommy tried to stand straighter, tried to look like the provider he’d forced himself to become. He held the newspapers against his chest. And if you look at that photograph now, if you know what to look for, you can see his knuckles white with the effort of gripping them. You can see the shadow under his eyes that speaks of sleepless nights and endless fever.

You can see the way his body angles toward the lamp post, using it for support while trying to appear strong. But what you can really see, what makes this photograph unbearable once you know the truth is the headline visible on the paper he’s holding.

Typhoid claims more victims, death toll rises in tenementss, contaminated water blamed. Tommy couldn’t read those words. He only knew they were selling well that day. Every customer wanted to know about the typhoid outbreak. Every mother buying a paper looked at him with fear, pulling their children away, not knowing that the boy selling them news of the disease was dying from it himself. The photographer took three shots.

Only one survived. In it, Tommy is looking directly at the camera with an expression that defies interpretation. pride, defiance, resignation, or simply the blank stare of a fever that had burned away everything except the will to remain standing. After the photographer left, Tommy continued selling papers. By noon, he’d sold all but 10.

His voice was gone, reduced to a whisper that customers had to lean close to hear. The fever had climbed so high that he’d stopped sweating. His body had no more water to give. But he kept standing, kept holding out papers. Kept making change with fingers that could barely feel the coins. At 12:25, Tommy started walking toward Chambers and Broadway. He had an appointment to keep. Mr.

Morrison would be there at 12:30, as he always was, five blocks. Tommy had walked five blocks thousands of times, but now each step required a negotiation with his failing body. Each breath was a victory against lungs filling with fluid. Each moment of consciousness was borrowed from a future that was rapidly running out. He made it three blocks before his legs gave out.

It happened in front of the immigrant savings bank, the place where Mr. Morrison worked. Tommy’s knees buckled and he fell forward, his newspapers scattering across the sidewalk like dead leaves. The 10 remaining copies of the New York World spread out in a fan pattern, their headlines about typhoid and death visible to every passer by who stepped over them, who stepped over him. But Tommy didn’t stay down.

Something in him, something that had nothing to do with courage and everything to do with necessity, made him gather those papers on his hands and knees, blood dripping from his mouth onto the newsprint. He collected every copy because those papers were worth 30 cents. 30 cents that could buy bread. 30 cents that could buy another day of medicine.

30 cents that meant something in a world where a 9-year-old’s life was worth less than that. He was still gathering the papers when Mr. Morrison found him. The banker had come out early, perhaps sensing something, perhaps simply needing air. He saw the crowd gathered on the sidewalk, saw them standing in a circle around something, and pushed through. There was Tommy on his knees trying to stack newspapers with hands that wouldn’t stop shaking, apologizing to the people stepping around him.

Sorry, sir. Sorry, ma’am. Papers for sale, fresh papers. Morrison dropped to his knees beside the boy. He felt Tommy’s forehead pulled his hand back from the heat. He saw the blood on the newspapers, the fever in the eyes that couldn’t quite focus on his face. And James Morrison, a man who’d spent his life counting other people’s money, made a decision that had nothing to do with arithmetic.

He gathered Tommy in his arms. The boy weighed nothing, just bones and fever and will. Morrison carried him into the bank, ignoring the protests of his supervisors, the shocked stairs of customers. He laid Tommy on a bench in the lobby and sent a runner for Dr. Goldberg, the same doctor whose card he’d given Tommy 3 days earlier. But Tommy wasn’t finished.

Even as his body was shutting down, even as the typhoid was completing its destruction, he had something important to say. He grabbed Morrison’s sleeve with fingers that had no strength left and pulled him close. “My ma,” Tommy whispered, tell her I sold all the papers. Tell her I was good at it, Morrison promised. Of course, he promised.

What else could he do? And Joey, Tommy continued, each word requiring enormous effort. Tell Joey the shoes. Tell him the shoes are his to keep. No taking them back. Dr. Goldberg arrived 20 minutes later, but there was nothing to be done. The typhoid had perforated Tommy’s intestines in multiple places. He was bleeding internally. His organs were shutting down.

The doctor did the only thing medical science could offer in 1908. He gave Tommy enough ldinum to stop the pain. In those last minutes, as the ldinum took hold, Tommy said something that Morrison would remember for the rest of his life, something that would haunt him, that would change him, that would make him spend the next 30 years advocating for child labor laws. Mr.

Morrison,” Tommy said, his voice suddenly clear. “Was I a good news boy?” Morrison, this banker who’d never cried in public, who’d been taught that men don’t show emotion, felt tears running down his face as he answered, “The best, Tommy. The very best.” Tommy smiled then, a real smile, not the grimace of pain he’d been wearing for days.

“Good,” he said. “Then Ma will be proud.” Thomas Sullivan died at 1:17 p.m. on March 15th, 1908 in the lobby of the Immigrant Savings Bank on Chamber Street. He was 9 years and 4 months old. The official cause of death, according to the single line in Belleview Hospital’s records when they came to collect the body, was typhoid fever.

But that doesn’t tell the whole truth. The truth is that Tommy Sullivan died of poverty. He died of a system that considered child labor a necessity. He died of contaminated water that the city knew about but didn’t fix. He died of being invisible in a city of millions. He died selling newspapers that announced the very disease that was killing him. Unable to read the warning that might have saved his life.

The first thing Mr. Morrison did after Tommy died was keep his promise. He walked the five blocks to the tenement on Orchard Street, climbed the four flights of stairs that smelled of cabbage and despair, and knocked on the door of the room where Margaret Sullivan was dying. She knew before he spoke.

Mothers always know. But Morrison told her anyway, told her that her son had sold all his papers, that he’d been the best news boy in New York, that he’d died thinking of her. Margaret Sullivan lived for six more days. The medicine Tommy had bought kept her comfortable, kept the pain at bay.

The neighbors, the same ones who’d complained about her coughing, now brought soup they couldn’t afford to share. Mrs. Goldstein from the bakery, brought bread. Big Mike Brennan, the tough king of the news boys, appeared at her door with an envelope containing $7.38 collected from every news boy who’d known Tommy. It was more money than most of them would see in a month.

On the sixth day, Margaret asked Mrs. Omali from next door to write a letter for her. The letter was addressed to Mr. Morrison at the immigrant savings bank. In it, she thanked him for his kindness to her son. She told him that Tommy had talked about him every night, that Morrison’s faith in him had meant more than the money, and she asked him for one last favor.

She asked him to make sure Tommy was buried properly, not in the potter’s field where the poor were thrown in unmarked graves. Margaret Sullivan died that night holding the photograph that the photographer had given her, the one of Tommy with his newspapers. She died believing her son had been somebody important, somebody worth photographing, somebody whose image would last. Morrison paid for both funerals.

He paid for a plot in Calvary Cemetery in Queens where Tommy and Margaret Sullivan could be buried together. He paid for a small headstone that read Thomas Sullivan 1899 1908 the best news boy in New York. It was a lie that was also the truth. Tommy had been one of thousands of news boys. But he had also been the best at what truly mattered, sacrificing everything for someone he loved. At the funeral, something unexpected happened.

News boys came. Not just a few, hundreds. They came from all five burrows, some walking for hours. They stood in their ragged clothes and worn shoes, caps in their hands, silent as the small coffin was lowered into the ground. Big Mike Brennan spoke for them all when he said, “Tommy Sullivan was one of us.

He died standing up. He died selling papers. He died like a news boy. Joey Matias was there wearing the shoes Tommy had bought him. He would wear those shoes until they fell apart and then he would keep the pieces. 40 years later, when Joey was Joseph Matias, owner of a successful printing company, he would keep those shoe remnants in a glass case in his office.

When people asked about them, he would tell them about a 9-year-old boy who gave him shoes when he was dying himself. He would tell them about Tommy Sullivan. But the story doesn’t end at the cemetery because Mr. Morrison, the banker who’d held a dying news boy in his arms, couldn’t forget. He couldn’t forget the question Tommy had asked.

Was I a good news boy? He couldn’t forget that a child had died proud of work that killed him. Morrison started writing letters to newspapers, to politicians, to anyone who would listen. He wrote about Tommy Sullivan and the 10,000 other news boys risking their lives for pennies. He wrote about children dying of preventable diseases while selling newspapers announcing their own deaths.

He wrote until his hands cramped, until his supervisors warned him he was endangering his position at the bank. In 1909, Morrison testified before the New York State Factory Investigating Commission. He brought the photograph with him, the one of Tommy holding the newspapers.

He held it up before the commissioners and said, “This boy couldn’t read the headline he was holding.” The headline said, “Tyoid claims more victims.” 3 days after this photograph was taken, he became one of those victims. His name was Tommy Sullivan. He was 9 years old, and he died believing that selling newspapers was more important than his life. The commission’s report published in 1911 led to some of the first child labor laws in New York State.

Children under 14 were prohibited from selling newspapers during school hours. Night work was banned for children under 16. It wasn’t enough, not nearly enough, but it was a beginning. And in the margin of the original report, preserved now in the New York State Archives, someone had written in pencil for Tommy Sullivan.

The photograph itself disappeared into the archives of the New York Public Library. For 93 years, it sat in a box labeled street scenes miscellaneous, 1908. It was a photograph of an anonymous news boy, one of thousands taken during the progressive era to document urban poverty. Nobody knew his name.

Nobody knew his story until 2001 when a graduate student named Patricia Chen was researching child labor for her dissertation. She found the photograph and was struck by something about it. Maybe it was the way the boy held those papers like they were precious. Maybe it was the headline visible in the image. Or maybe it was something in his eyes, that direct stare that seemed to challenge the viewer to see him, really see him. Chen spent 6 months tracking down the story.

She found Morrison’s testimony to the commission. She found the death records at Belleview. She found the burial plot at Calvary Cemetery. The headstone now worn almost smooth but still readable. The best news boy in New York.

She found Joey Matias’s descendants who still had the pieces of those shoes in a safety deposit box along with a letter Joey had written but never sent thanking a boy who’d been dead for 40 years. In 2002, Chen’s research was published in the Journal of American History. The photograph of Tommy Sullivan was printed alongside the article. For the first time in 94 years, the boy in the photograph had a name. He had a story.

He had a life that mattered beyond the moment captured in that image. The photograph now hangs in the Museum of the City of New York, part of their permanent collection on immigration and labor. The caption reads, “Thomas Tommy Sullivan, age 9, news boy, died of typhoid fever 3 days after this photograph was taken. March 15th, 1908.

The headline he holds announces the epidemic that would claim his life.” Every year, school groups come through the museum. They stop at Tommy’s photograph. Teachers explain about child labor, about progressive reform, about how things used to be. Most of the students walk by quickly, eager to see more exciting exhibits. But sometimes a child stops. Sometimes a child really looks.

Sometimes a child sees not a historical artifact, but another child. One who worked 14-hour days, who couldn’t read, who died at 9 years old believing he’d done something good. And sometimes, very rarely, someone leaves flowers beneath the photograph. Nobody knows who does this. The museum staff find them in the morning.

Fresh daisies, the kind that grow wild in empty lots, the kind that poor children pick for free. They leave them there until they wilt. These offerings to a news boy who died selling news of his own death. Dr. Abraham Goldberg, the physician Morrison had recommended, kept a diary. In it, he wrote about March 15th, 1908. Today, a child died in my care.

Thomas Sullivan, news boy, aged 9 years, typhoid fever, advanced stage. He died concerned not for himself, but for his mother’s welfare. In 30 years of medicine, I have never seen such courage in one so young. I have saved many lives, but I could not save his. I fear I will remember this failure forever.” The entry continues.

The boy asked if he had been a good news boy. What kind of world makes a dying child’s last concern? Whether he was good at the job that killed him? What kind of city sends children to sell newspapers in a typhoid outbreak? We call ourselves civilized. We are barbarians in wool coats. But perhaps the most powerful testament to Tommy’s life came from an unexpected source.

In 1938, 30 years after Tommy’s death, Big Mike Brennan was Michael Brennan, a successful businessman who owned a chain of news stands across Manhattan. He was interviewed by the Federal Writers Project, one of the New Deal programs collecting oral histories of American life.

When asked about his childhood as a news boy, Brennan said this. There was this kid, Tommy Sullivan, little Irish runt, maybe 9 years old. I knocked him down once for trying to take my corner. Kid got back up, blood all over his face and kept selling papers. Last day I saw him, he was dying on his feet, burning with fever. Still selling papers, still trying to make enough to help his ma.

I gave him my coat that day. Only kind thing I ever did as a kid. Wasn’t enough. Nothing was ever enough for kids like us. But Tommy, he never stopped trying. He died standing up holding those papers like they were made of gold. Every success I’ve had, every news stand I’ve opened, I think about Tommy Sullivan. I think about all the kids who didn’t make it out.

He’s the reason I hire kids off the street. Give them a chance. It’s not charity. It’s a debt. A debt to a 9-year-old boy who showed me that even when the world’s killing you, you stand up. You keep selling. You take care of your own. The interview continues. You want to know what poverty really is? It’s not being hungry, though God knows we were hungry.

It’s not being cold or sick or scared. Poverty is dying at 9 years old and being grateful you were good at selling newspapers. Poverty is your mother following you to the grave 6 days later because you were the only thing keeping her alive. Poverty is having your story forgotten for 90 years because nobody thought to ask your name.

Today, if you know where to look, you can find Tommy Sullivan everywhere in New York. He’s in every child who has to grow up too fast. He’s in every parent working multiple jobs to pay for medicine. He’s in every photograph of someone whose name we’ll never know, whose story we’ll never hear. He’s in the space between what we promise children and what we actually give them.

But most of all, Tommy Sullivan lives in that photograph. That single moment when a dying child stood straight and proud, holding newspapers he couldn’t read, selling stories that weren’t his, dying of a disease he was warning others about. Look at it carefully.

Look at the boy who thought being a good news boy was the most important thing in the world. Look at the headlines he’s holding. Look at the date, March 15th, 1908. Remember that 3 days later he was dead. Remember that his mother followed him within a week. Remember that it took 93 years for anyone to learn his name. And then ask yourself, how many Tommy Sullivanss are out there right now? How many children are we failing to see? How many are dying of preventable things while we debate the cost of prevention? How many are holding up headlines about

their own tragedies, unable to read the warning signs? The photograph of Tommy Sullivan isn’t just a historical artifact. It’s a mirror. It shows us who we were. It warns us who we might still be. It challenges us to see the children standing on our own corners, selling their childhood for survival, dying of diseases we know how to prevent, disappearing into statistics without names.

Tommy Sullivan sold newspapers for 3 years. He lived for nine. He’s been dead for over a century. But in that photograph, he’s eternal. Forever nine. Forever holding those papers. Forever looking directly at us, asking the only question that mattered to him. Was I good enough? Did I do enough? Did I matter? The answer is in the photograph itself. In the fact that it survived.

In the fact that you now know his name. In the fact that a 9-year-old news boy who couldn’t read the headlines that killed him has become a headline himself. A story that refuses to disappear. A child who mattered then and matters now and will matter as long as there are children forced to sell their childhood on street corners.

Tommy Sullivan was the best news boy in New York. Not because he sold the most papers, not because he worked the longest hours, but because he proved that even the smallest, poorest, most invisible child can leave a mark on history. Sometimes that mark is a photograph. Sometimes it’s a memory. Sometimes it’s just a pair of worn shoes kept for 40 years by another child who survived.

But it’s always proof that we were here, that we mattered, that we stood up and kept selling papers even when the world was ending. That’s what Tommy Sullivan teaches us. That’s why his photograph endures. That’s why 116 years later, we’re still telling his story. Look at the photograph one more time. See the boy, not the symbol.

See Tommy Sullivan, age nine, who loved his mother, who shared his shoes, who died thinking he’d done good. See him and remember, because remembering is the only justice we can offer now. Remembering is how we pay our debt to all the children who held tomorrow’s headlines in their hands while living yesterday’s tragedies. This is what remains when we’re gone.

A photograph, a name finally spoken. A story finally told. Tommy Sullivan, the best news boy in New York, who sold papers until his last breath. Who died warning about the disease that killed him. Who asked only if he’d been good enough. He was. God help us all. He was more than good enough. He was extraordinary and he was 9 years old.

Before we close, remember this is a dramatized story inspired by real historical conditions and records from the era. It’s fiction that tries to honor truths children like Tommy lived. If there’s a lesson here, it’s that dignity can exist even in the harshest poverty and that a society is measured by how it guards the small, the unseen, and the voiceless.

Ask yourself, when have you looked past someone who needed to be seen? What responsibilities do we share when a warning is written right in front of us and we choose not to read it? Which small mercies from strangers have changed the course of a life? Maybe yours or someone in your family’s past.

If this story stayed with you, write the word remembered in the comments so I know you were here to the end. Tell me the city you’re watching from and only if you feel comfortable. Share a memory from your family’s older generations that deserves to be preserved. It may inspire future dramatized histories on this channel. Thank you for spending this time with a difficult but vital tale.