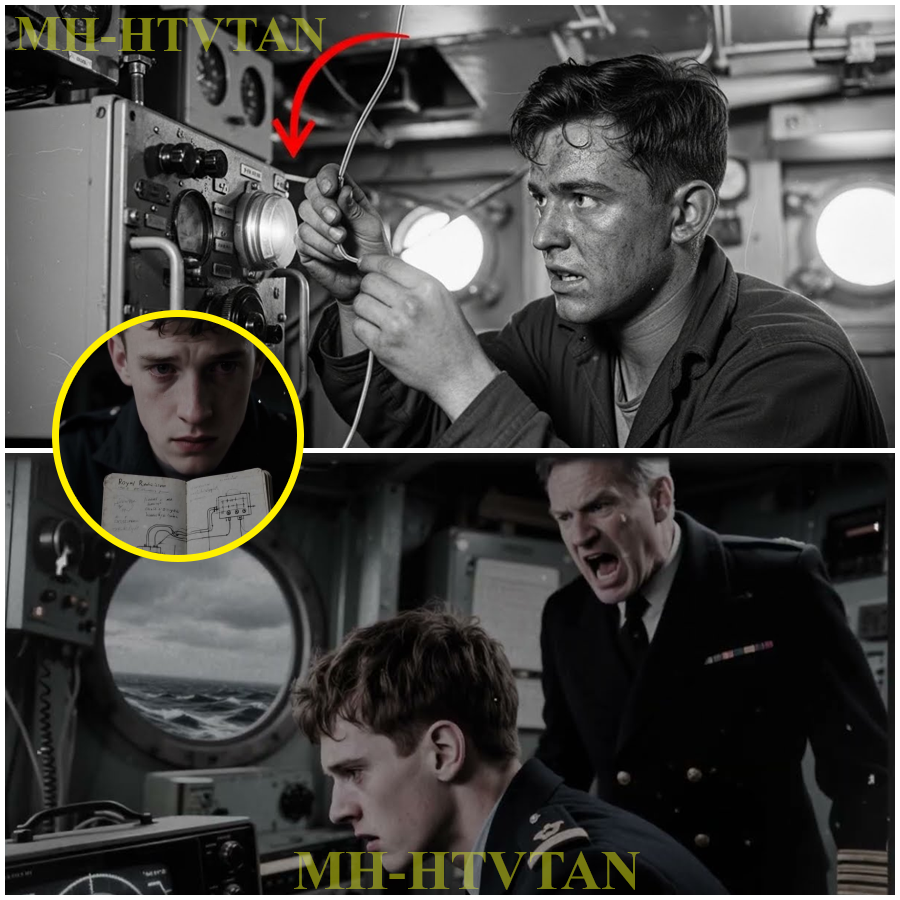

February 1943, the North Atlantic. A young radio man’s hands are shaking. And it’s not from the cold. He’s about to do something that could get him court marshaled. Something that breaks every regulation in the Royal Navy handbook. But if he doesn’t do it in the next 60 seconds, 23 ships in his convoy are going to die. The Ubot are closing in.

His commanding officer is screaming at him to get a fix on the German transmission. But the standard antenna setup isn’t working. The signal is too weak, too fleeting, lost in the storm of static and the howling Atlantic wind. So he does the unthinkable. He reverses the wire, hooks it up backwards, upside down, exactly the way they told him never to do it in training. And suddenly the oscilloscope screen explodes with clarity.

A perfect bearing. The Ubot’s position clear as day. Within an hour that yubot is on the ocean floor. The convoy is saved. And the radio man, he’s facing a tribunal for equipment tampering. But 3 weeks later, his forbidden technique will be quietly distributed to every destroyer in the Atlantic fleet.

No credit given, no apology issued, just results. This is the story of how desperation, innovation, and a little bit of rulebreaking turned the tide in the longest battle of World War II. To understand why this moment mattered, you need to understand just how badly the Allies were losing the Battle of the Atlantic in early 1943.

Every day, German Ubot were sending Allied merchant ships to the bottom of the ocean. Not one or two, dozens. In the first 20 days of March 1943 alone, the Germans would sink 97 Allied ships. That’s almost five ships per day. Five ships full of food, fuel, weapons, and men. Britain was starving. Soviet Russia was running out of supplies.

The planned invasion of Europe was becoming impossible because they couldn’t guarantee the ships would even make it across the Atlantic. Winston Churchill would later write that the Yubot peril was the only thing that truly frightened him during the entire war. Not the Lufafa bombing London, not the threat of invasion, the Ubot. Because unlike armies or bombers, Ubot were invisible.

They struck from beneath the waves, often at night, and vanished before anyone could respond. By the time a destroyer reached the position where a torpedo had been fired, the yubot was long gone. Running silent, running deep, impossible to find in the vast emptiness of the Atlantic. The Germans had perfected their wolfpacked tactics.

A group of Ubot would position themselves across the convoy routes. When a convoy was spotted, one Ubot would shadow it, radioing constant updates to headquarters. Then headquarters would vector in every available Ubot in the area, creating a wolf pack of 10, 15, sometimes 20 submarines. They would wait until nightfall.

Then they would surface and attack from multiple directions simultaneously. Chaos, fire, explosions, men drowning in freezing water thick with oil. The escort ships, usually just a handful of destroyers and corvettes, were overwhelmed. They couldn’t protect every merchant ship. They couldn’t even locate where the attacks were coming from.

By the time they rushed to one side of the convoy, another ship was torpedoed on the opposite side. And here’s the worst part. The Allies had the technology to fight back. It was called HFDF, highfrequency direction finding. The sailors called it Huffduff. Huffduff was brilliant, revolutionary actually. It was invented by a British scientist named Robert Watson Watt back in the 1920s.

Originally designed to track lightning strikes. The principle was simple but powerful. When a radio transmits, it sends out electromagnetic waves in all directions. If you have two antennas arranged at right angles, and you feed their signals into an oscilloscope, the beam on the screen will draw a line pointing directly at the transmitter.

Instantaneous, automatic. No need to slowly rotate a loop antenna and listen for the signal to fade. Just look at the screen and read the bearing. For the Battle of the Atlantic, this was supposed to be a gamecher. The Ubot had to radio their positions to coordinate attacks.

Every time they transmitted, even for just a few seconds, Huffduff could pinpoint exactly where they were. In theory, in reality, shipboard Huffduff was a nightmare. See, Watson Watt had designed the system for land-based stations where you could mount your antennas away from buildings and interference. But on a warship, you had a steel hall superstructure, masts, radar antennas, gun turrets, all creating electromagnetic interference and distorting the incoming radio waves.

The signal would bounce off the ship’s own structure before reaching the antenna. The bearing would be wrong. Sometimes by just a few degrees, sometimes by 40 or 50°, which when you’re talking about detecting a yubot 10 or 20 m away, meant you’d be looking in completely the wrong direction. The Admiral knew about this problem.

They tried to solve it by calibrating each ship individually. They’d anchor the ship in harbor, have another ship sail around, broadcasting test signals from different directions, and create correction cards for the Huff-Duff operator. But here’s the thing. Those calibrations were done in calm harbors.

They were done in specific frequencies. They didn’t account for the ship rolling and pitching in heavy seas. They didn’t account for salt spray coating the antennas. They didn’t account for the operator himself having to work in a tiny cramped radio room, exhausted after days without sleep, trying to read a flickering oscilloscope while the ship is being thrown around by 20ft waves.

And they definitely didn’t account for what happened when the Ubot changed their transmission frequencies to avoid detection. The calibration cards were useless if the signal came in on a different wavelength than what was tested. So by February 1943, the Royal Navy had installed Huff-Duff equipment on dozens of convoy escorts. They had trained hundreds of operators. They had spent millions of pounds on the technology.

And it wasn’t working well enough. The Ubot were still winning. The convoys were still dying. and radio across the Atlantic fleet were getting increasingly desperate as they watched ships explode and couldn’t get accurate bearings on the attackers. Now, we need to talk about the radio man himself.

History hasn’t preserved his name, which is fitting because what he did was never officially acknowledged, but we know enough to piece together what happened. He was young, probably early 20s. He’d been trained at one of the Royal Navy signal schools where they drilled into you the absolute importance of following procedures exactly.

Equipment was expensive. Equipment was precision calibrated. Tampering with equipment was a court marshal offense. But he’d been at sea long enough to know that textbook procedures and realworld conditions were two very different things. He’d seen it happen too many times. A yubot would transmit.

He’d catch the signal on his huff set. The oscilloscope would show a bearing. He’d report it to the bridge. The destroyer would race off in that direction at flank speed and find nothing. Or worse, while the destroyer was off searching in the wrong direction, another ship in the convoy would be torpedoed from a completely different bearing. He started keeping notes, unofficial, unauthorized notes.

Every time he got a huff duff bearing, he’d write it down along with where the hubot actually turned out to be, if they ever found it at all, where the attack actually came from. And he started to see a pattern. The bearings weren’t just randomly wrong. They were consistently wrong in specific ways.

When signals came from certain directions, the error was always about the same. The calibration cards weren’t accounting for something, some variable that changed how the signal arrived at his antenna. He started experimenting during quiet watches. Nothing official, nothing documented. Just trying different adjustments to see if he could improve accuracy.

He tried repositioning himself in the radio room, thinking maybe his own body was interfering didn’t help. He tried cleaning the antenna connections more frequently. marginal improvement. He tried adjusting the amplifier settings beyond the specified ranges. Sometimes better, sometimes worse. And then one night during a routine equipment test, he made a mistake. He was exhausted, running on coffee and adrenaline, and he connected one of the antenna feeds backwards, reversed the polarity, the exact thing you were never supposed to do because it would supposedly damage the receiver or give

completely false readings. Except it didn’t. The test signal came through clearer than it ever had before. The oscilloscope pattern was sharper. The bearing was more defined. He stared at that screen for a long moment. Then he checked the wiring, confirmed what he’d done, and very carefully wrote down every detail in his unauthorized notebook. He didn’t tell anyone.

Not yet, because what he discovered went against everything in the technical manuals, against everything his instructors had taught him. And if he was wrong, if this was just a fluke of that particular test signal, he’d look like a fool. or worse, he’d be disciplined for unauthorized modifications. But he kept the wiring diagram, and he waited for a chance to test it under real conditions. That chance came in February 1943.

His convoy was designated SC118, 63 merchant ships, mostly carrying supplies from New York to Liverpool. The escort was under mann just six vessels, because so many ships were needed elsewhere. They’d been at sea for 8 days. The weather was brutal. Freezing rain, heavy seas, visibility near zero, which meant the Ubot couldn’t see them easily. But it also meant the convoy couldn’t see the Ubot.

On the night of February 4th, the first ship was torpedoed. A tanker hit a midship, exploding in a ball of flame that lit up the entire convoy. 2 minutes later, another explosion. Another ship gone. The Huffed Duff operator, a radio man, was already at his station.

He’d been monitoring the frequencies, and he’d caught a brief transmission just before the first torpedo hit. Standard Ubot contact report. The shadow was calling in the Wolfpack. He’d gotten a bearing, fed it to the bridge. But even as he did, he knew it was wrong. He could feel it. The signal had that characteristic distortion pattern he’d been tracking. The bearing was probably off by at least 20°, maybe more.

The destroyer captain didn’t know that. He took the bearing and ordered the helm to turn toward it, preparing to launch a depth charge attack, which meant they were about to go in completely the wrong direction. While Ubot were actively torpedoing the convoy, the radio man stared at his equipment, at the wiring diagram he’d hidden in his notebook, at the regulation mandated configuration that he knew wasn’t working, and he made a decision. He told the bridge he needed 2 minutes to fix a technical problem.

The captain, dealing with multiple crisis situations simultaneously, barely acknowledged him. 2 minutes. That’s all he had. His hands were steady as he opened the equipment panel. As he disconnected the antenna feed, as he rewired it in the configuration he tested weeks ago, the Forbidden configuration, he powered the equipment back up, held his breath as the tubes warmed, watched the oscilloscope flicker to life, and then another Yubo transmitted.

The screen lit up with a clear, sharp, unmistakable bearing. completely different from what he would have gotten with standard wiring. About 35 degrees off, he grabbed the voice tube to the bridge and called out the new bearing with absolute conviction in his voice. There was a pause. The captain asked if he was sure because it was significantly different from his previous report. He said yes.

He was not sure. He was terrified, but he said yes. The destroyer altered course to the new bearing. Engines at full ahead, racing through the darkness and the storm toward where he’d said the hubot would be. For 3 minutes, nothing. The longest 3 minutes of his life. Then the radar operator called out a contact. Surface target. Range 4,000 yd. Moving slowly.

It was a yubot running on the surface to keep up with the convoy, probably preparing to dive and attack again. The destroyer opened fire, illuminated the target with search lights. The Ubot crash dived, but it was too late. Depth charges followed it down. The sonar operator reported breaking up noises. One Uboat destroyed, but more importantly, one accurate Huff-Duff bearing. proof that the unauthorized modification worked.

You might think that this is where the story gets triumphant, where the radio man is praised and his innovation is rapidly adopted. That’s not what happened. What happened was that when the destroyer returned to port, the radio man was immediately summoned to meet with the communications officer. His equipment was inspected. The unauthorized wiring modification was discovered and he was placed under investigation for teing with vital equipment.

The official report stated that Abel Seaman so and so had violated regulations by modifying Huffduff equipment without authorization. The report recommended disciplinary action. But here’s where it gets interesting. That report went up the chain of command to the Admiral T signal establishment. And someone there, some engineer or scientist whose name has also been lost to history, actually looked at what the radio men had done.

And they ran tests. They took a ship, anchored it in Scappa Flow, and they tried the modification. Standard wiring versus reversed wiring. dozens of test signals from different directions, different frequencies, different conditions, and the unauthorized modification worked better, consistently better, especially under the exact conditions that were most common in the North Atlantic, rough seas, storm interference, signals at the edge of reception range. The reason it worked was something the original designers hadn’t fully appreciated. The way

electromagnetic waves interact with a steel ship’s hall creates a phase shift in the incoming signal. The standard wiring configuration added that phase shift to the signal. The reversed wiring configuration subtracted it which effectively canceled out some of the distortion. It was accidental genius. The radio man hadn’t understood the physics.

He just observed the results and had the courage to trust his observations over the official procedures. But the Admiral T had a problem. If they officially admitted that a lowly able seaman had discovered a critical flaw in equipment that had cost millions of pounds and months of scientific development, it would be embarrassing.

It would raise questions about why the Admiral Tzone experts hadn’t discovered this sooner. It might even affect morale if it became widely known that the Huff-Duff equipment had been giving wrong bearings for months. So, they did what bureaucracies often do. They quietly fixed the problem while publicly ignoring it. The investigation into the radio man’s conduct was dropped.

No punishment, but also no commenation, no recognition. He was just reassigned to another ship with a notation in his file that said he’d shown initiative under difficult circumstances. Meanwhile, the Admiral Ty issued a classified technical bulletin to all ships equipped with Huff Duff. It described a refinement to antenna configuration that improves bearing accuracy under adverse conditions.

It included detailed wiring diagrams. It made the modification mandatory on all vessels. It did not mention who had discovered it. Within 6 weeks, every Huffduff equipped ship in the Atlantic fleet had been modified. The radioman noticed. They talked among themselves, of course.

Rumors spread about the upside down wire and the sailor who’d figured it out, but officially it never happened. And the effect on the Yubot war was dramatic. March 1943 was supposed to be Germany’s month of triumph in the Atlantic. Admiral Dunits had more Yubot operational than ever before. Over a 100 submarines were prowling the convoy roots.

He believed he was on the verge of cutting Britain off completely, forcing a negotiated peace. The first three weeks seemed to prove him right. 97 Allied ships sunk. It was the worst month of the entire Battle of the Atlantic. But then something changed. The Ubot started dying. Not occasionally, not at the slow attrition rate the Allies had managed before. They started dying frequently, consistently, in numbers that shocked the German naval command.

In the last 10 days of March, the Allies sank 15 Ubot. In April, another 15. In May, 41 Ubot were destroyed. 41. That was more than denit’s shipyards could replace. For the first time in the entire war, ubots were being sunk faster than new ones could be built. On May 24th, 1943, Dunit did something unprecedented.

He ordered all yubot to withdraw from the North Atlantic convoy routes. The Wolf Packs were pulled back. The siege of Britain was over. Historians usually attribute this turning point to a combination of factors. More escort carriers providing air cover, better radar, improved sonar, the breaking of German codes giving advanced warning of viewboat positions, the closing of the Mid-Atlantic air gap where planes couldn’t reach. All of those things mattered. All of them contributed.

But there’s a statistic that doesn’t get mentioned as often. In the period after the Huff-Duff modifications were implemented, bearings from shipboard direction finding equipment became accurate enough to guide ships directly to yubot positions over 70% of the time. Before the modifications, it had been less than 40%.

That improvement, that single technical fix discovered by one exhausted radio man trying to save his convoy meant that every time a yubot transmitted, it was painting a target on itself. The German Navy knew the Allies had directionfinding equipment they’d known since before the war started. That’s why they developed the Kurt Signnali system, short pre-coded messages that could be transmitted in as little as 20 seconds.

What they didn’t know was that the ALIS had figured out how accurate bearings from those brief transmissions from a rolling pitching destroyer in the middle of a storm from signals at the very edge of reception range. The Ubot thought they were safe if they kept their transmissions short. They weren’t.

Every message sent was a death sentence and they had to send messages because the Wolfpack tactics required coordination. So the Germans faced an impossible choice. Stop communicating and abandon their effective tactics or keep communicating and die. They chose to keep communicating. They had to and they died.

By the end of May 1943, 30,000 German sailors had been killed in yubot. 783 submarines had been lost. The Battle of the Atlantic, which had lasted for nearly four years, was effectively over. The Allies would lose more ships to Ubot in the remaining 2 years of the war. But never again would the Germans come close to cutting the Atlantic supply lines.

Never again would Churchill lie awake at night, fearing that Britain would starve before America could intervene. The invasion of Normandy became possible because ships could cross the Atlantic safely. The strategic bombing campaign against Germany succeeded because fuel could be transported. The Soviet Union held on because supplies could reach Mormons. All of it depended on winning the Battle of the Atlantic.

And winning the Battle of the Atlantic depended on many things, but one of those things was an unauthorized wire modification that nobody wanted to talk about. This story, even with its missing details and lost names, tells us something important about how wars are actually won. We like to think that wars are won by brilliant generals in great strategies, by politicians making the right decisions at the right time, by scientists in laboratories developing super weapons.

And all of that matters. All of it helps. But wars are also won by ordinary people thrust into desperate situations who have the courage to question authority and try something different. Think about what that radio man did. He was nobody. He had no advanced degree in electrical engineering. He couldn’t have written a theoretical paper on electromagnetic wave propagation.

He was just a kid trained to operate equipment, following procedures, doing his job. But he paid attention. He noticed patterns. He kept records when he wasn’t supposed to. He experimented when it was forbidden. And when the moment came, he trusted his own observations more than he trusted the instruction manual.

That kind of practical innovation happens constantly in wartime, but it rarely gets recorded. The official histories credit the scientific establishments, the research laboratories, the formal chains of command. They don’t mention the corporal who figured out a better way to waterproof ammunition, or the mechanic who discovered that you could coax more power from an engine by violating the maintenance manual, or the radio man who wired his antenna upside down. And yet, those innovations multiplied across thousands of individuals often make the difference

between victory and defeat. The tragedy is how often those innovations are resisted. How often the first response from authority is punishment rather than praise. How often good ideas get buried because they didn’t come from the right person or through the right channels. The radio man was lucky.

His discovery was too useful to ignore. The timing was too critical. The need was too desperate. So after the initial bureaucratic panic, common sense prevailed and the modification was implemented. But how many other innovations were lost because the timing wasn’t right? Because the evidence wasn’t quite conclusive enough? Because the person who discovered them didn’t survive to share them? Because someone in authority decided that maintaining proper procedures was more important than winning the war. We’ll never know.

That’s the nature of lost history. What we do know is that innovation rarely comes from where you expect it. It doesn’t wait for permission. It doesn’t follow org charts. It emerges from the people who are actually dealing with the problem, not the people who are theorizing about it.

The scientists who designed Haftduff were brilliant. Watsonwatt was a genius. The engineers at the Admiral T signal establishment were highly trained experts. But they designed the system on land. They tested it in controlled conditions. They couldn’t anticipate every variable that would emerge when you mounted that equipment on a destroyer in the North Atlantic.

The radio man could anticipate those variables because he lived with them every day. He felt the ship roll. He watched the spraycoat his antennas. He saw the bearings fail in real time while men died. So, he found a solution that worked, even if he didn’t understand why it worked. That’s not a failure of the scientific method. That’s the scientific method working exactly as it should.

Observe, hypothesize, test, revise. It just happened to occur in a radio room instead of a laboratory. You might be wondering why this 80-year-old story matters today. We’re not fighting Ubot anymore. Most of us will never face life or death situations where we have to choose between following procedures and trusting our observations.

But the fundamental tension in this story still exists everywhere. In corporations where employees see problems that management doesn’t want to acknowledge. In government agencies where frontline workers know the regulations aren’t working but can’t get anyone to listen. In hospitals where nurses know better ways to care for patients, but the official protocols say otherwise.

The instinct to punish unauthorized innovation is still alive and well because innovation is disruptive. It challenges authority. It implies that the people in charge make mistakes. It threatens the comfortable assumption that if everyone just follows the rules, everything will work out fine. But the rules are written for average conditions, normal circumstances, predictable situations.

Real life is rarely average, normal, or predictable. The people who succeed, who solve problems, who make breakthroughs are the ones who learn when to follow the rules and when to break them. They develop judgment. They build expertise. They pay attention to what actually works rather than what’s supposed to work.

And most importantly, they have the courage to act on that knowledge even when it’s risky. The radio man risked his career. He risked court marshal. He risked being labeled as reckless or insubordinate. He took that risk because lives were at stake and he believed he had a better solution. He was right, but he could have been wrong. A modification might not have worked. The bearing might have been even more inaccurate.

The destroyer might have gone in the wrong direction, failed to find the yubot, and more ships might have died, or they were off searching uselessly. That’s the burden of innovation. You rarely have certainty. You have to act on incomplete information, making your best judgment, accepting that you might fail. Most people aren’t willing to take that risk.

It’s safer to follow orders, stick to procedures, let someone else make the decisions. If things go wrong, you can say you did what you were told. Nobody can blame you. Except sometimes following orders is the wrong choice. Sometimes the procedures are inadequate. Sometimes the people in charge don’t have the information they need to make good decisions.

And in those moments, the people who make a difference are the ones who step up and say, “I see a better way. I know this is against the rules, but I think it’s worth trying. That’s what happened in February 1943 in the North Atlantic. One person faced with an impossible situation chose to trust their own judgment over official procedures. It changed the course of the war. We don’t know the radio man’s name.

We don’t know if he survived the war. We don’t know if he ever learned how important his discovery was or if he spent the rest of his life thinking he’d just been lucky once. What we do know is that by late 1943, when the historian Samuel Elliot Morrison was researching the Battle of the Atlantic, he wrote that Huffduff had contributed to approximately 24% of all yubot kills, one in four.

And the improvement in accuracy that made that possible came from one unauthorized modification spread quietly throughout the fleet, never officially acknowledged. That’s how history actually works. The textbooks will tell you about the great men and the big decisions. They’ll talk about Churchill and Roosevelt, about radar and sonar, about codereing at Bletchley Park.

All of that is true and important, but they probably won’t tell you about the radio man who wired his antenna upside down. About the 3 minutes of terror while a destroyer raced toward where he said a Uboat would be. About the relief when the radar contact appeared, and he knew he’d been right.

They won’t tell you about the bureaucrat at the Admiralty who could have buried the discovery out of embarrassment, but chose to implement it instead. about the engineers who studied what an untrained seaman had figured out by trial and error and incorporated it into official procedure. They won’t tell you about the thousands of sailors who never knew that the huff equipment that kept them alive was working because someone had broken the rules. But those are the stories that matter.

Those are the moments when ordinary people facing impossible odds found a way to push back against the darkness just a little bit more. The Atlantic didn’t turn because of one discovery. It turned because of a thousand discoveries, a thousand innovations, a thousand moments of courage. Most of them forgotten, all of them essential. This was just one of them.

One wire reversed, one regulation broken, one bearing accurate enough to save a convoy, and maybe, just maybe, accurate enough to change the world.