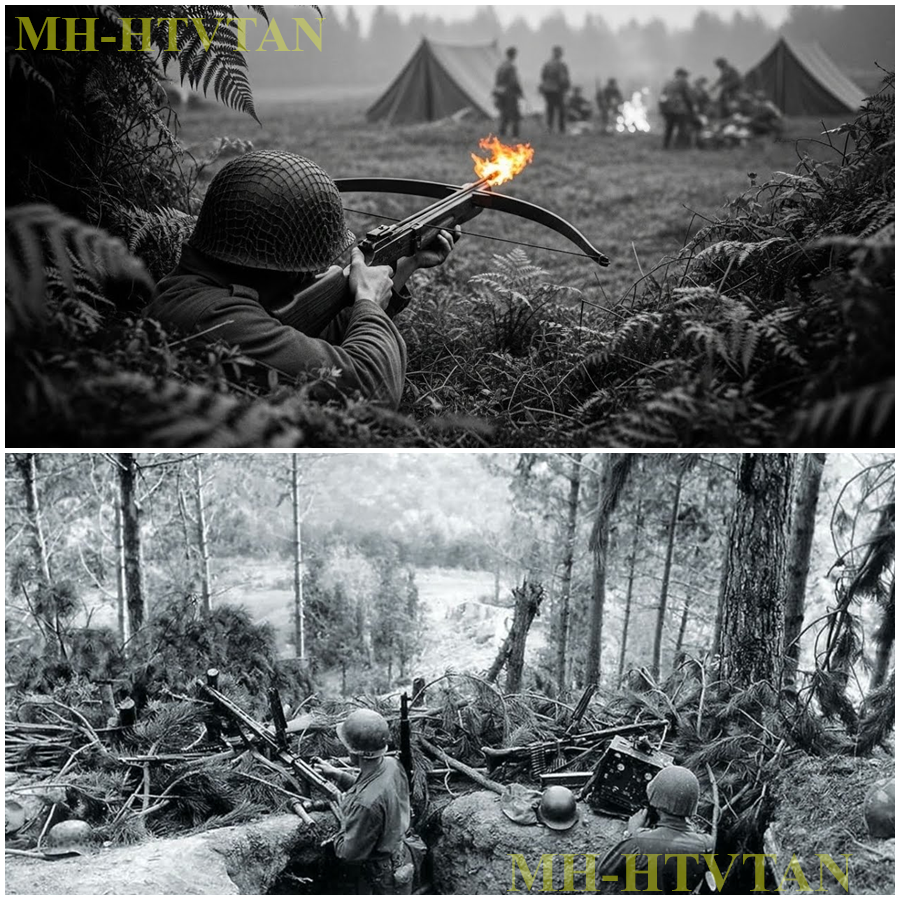

At 11:47 p.m. on March 14th, 1944, Sergeant William Bill Hartley crouched in a bombedout factory basement outside Casino, Italy, staring at what his officers called the stupidest weapon modification they’d ever seen. He’d wrapped oil soaked rags around six crossbow bolts, sealed them with pine resin, and rigged a crude ignition mechanism using match heads and friction strips. The officers laughed. The other sergeants shook their heads.

One lieutenant actually ordered him to disassemble the contraption before he burned himself to death. In less than 3 hours, Hartley would use that mocked fire arrow crossbow to incinerate seven German officers in their command post, destroy their communication equipment, and create enough chaos to allow 23 trapped American soldiers to escape a kill zone they’d been pinned in for 6 days. The Germans would call it hullenfo, hellfire.

The Americans would call it the most audacious improvised weapon assault of the Italian campaign. The crossbow itself was a curiosity. A German hunting weapon Hartley had scavenged from a destroyed farmhouse two months earlier. Compound steel construction, 60 lb draw weight, effective range of 80 yards.

He’d kept it as a novelty, using it occasionally for silent sentry elimination when noise discipline was critical. But the fire arrow modification that came from pure desperation and a childhood in the West Virginia coal country that taught him everything about combustion, ventilation, and how fire behaves in confined spaces.

William Hartley grew up in Beckley, West Virginia, the third son of a coal miner who died of black lung when Bill was 14. By 15, he was working the mines himself, following his father into the darkness that killed most men before they reached 50. The work was brutal, dangerous, and taught lessons you couldn’t learn anywhere else.

How to move in pitch darkness, how to judge air quality by smell. How to understand structural weakness in timber supports. And most importantly, how fire moved through enclosed spaces, consuming oxygen, creating backdrafts, turning wooden support beams into accelerants. The mine owners called them fire bosses, men who understood combustion well enough to prevent methane explosions. By 18, Hartley was one of them.

He was 26 when Pearl Harbor happened. Married with a daughter, exempt from the draft due to his critical mining job. He enlisted anyway. His wife didn’t speak to him for a week. His explanation was simple. Can’t send other men to do what I won’t do myself. The words sounded noble. The truth was more complicated.

He’d seen too many men die in the mines because supervisors made decisions from comfortable offices. He wasn’t going to be the man who stayed home while others fought. Basic training at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, revealed talents the army didn’t know what to do with. Hartley was an excellent shot, but not exceptional. Good with a knife, but not remarkable.

What set him apart was problem solving under pressure and an ability to exploit terrain and structures that baffled his instructors. During one exercise, he infiltrated a mock enemy position by crawling through a drainage culvert the officers didn’t know existed.

During another, he eliminated three enemy sentries using nothing but a length of wire and patience. His superiors noted, “Unconventional thinker may prove useful in irregular warfare.” The Italian campaign was irregular warfare perfected into hell. Hartley’s unit, Second Battalion, 36th Infantry Division, hit the beaches at Solerno in September 1943 and hadn’t stopped bleeding since. Anzio, the Gustav line, Monte Casino.

Names that would haunt survivors for decades. By March 1944, they were part of the grinding assault on Casino Town, a medieval maze of rubble and death, where every building was a fortress and every street a kill zone. The situation that led to the Fire Arrow mission developed over 6 days of catastrophic tactical failure.

On March 8th, Captain James Morrison led a two squad patrol, 23 men total, into the industrial sector east of Casino to gather intelligence on German artillery positions. The mission briefing estimated light enemy presence. Intelligence was wrong. Morrison’s men walked into a reinforced German defensive position.

Roughly 60 soldiers from the first Falerm Jagger Division. elite paratroopers who’d turned a cluster of factory buildings into an interlocking fortress. The American patrol took casualties immediately. Corporal Eddie Vasquez, aged 20, from El Paso, died in the first burst of machine gun fire.

Private First Class Robert Chen, aged 19, from San Francisco, took shrapnel to the legs and couldn’t walk. The survivors, 21 men now, retreated into a partially collapsed factory building with a stone foundation and heavy walls. Good for defense, perfect for a trap. The Germans didn’t assault. They didn’t need to. They surrounded the position, set up machine gun nests covering every exit, and waited.

No food would reach the Americans, no water, no ammunition resupply. The enemy could afford patience. Captain Morrison radioed for relief. Division command reviewed the tactical situation and delivered the verdict. Survivors would never forgive. Hold position. Relief force being organized. That was March 8th.

By March 10th, the trapped men were rationing water by the capful. Morrison radioed again, more desperate. Men dehydrating. Two wounded critical. Request immediate relief. Command response. Air support unavailable due to weather. Ground relief delayed by enemy strength. Translation: You’re expendable. Hold until you die and will retake the position with your bodies in it.

By March 12th, Private Chen was delirious with infection. Another soldier, Private Michael Kowalsski, aged 22, from Detroit, had stopped responding to commands simple dehydration psychosis. Morrison’s radio messages became, “Please, command’s responses became,” silence.

On March 13th, American artillery tried to suppress the German positions enough for an armored relief column to break through. It failed. Two Sherman tanks were destroyed. 14 more casualties. The relief attempt was abandoned. Hartley heard Morrison’s radio transmissions from the battalion command post where he was pulling guard duty. He knew Morrison. They’d served together at Solerno.

Shared cigarettes during the Anio stalemate. argued about baseball and politics with the easy familiarity of men who trusted each other completely. Hearing Morrison’s voice crack as he described men dying of thirst while Germans laughed from 50 yards away broke something in Hartley. When his guard shift ended at 6:00 p.m.

on March 13th, he didn’t return to his barracks. He went looking for the battalion intelligence officer. Lieutenant Peter Kowalsski, no relation to the trapped private, was a former seminary student from Chicago who approached war with the analytical detachment of a chess player when Hartley found him at 7:30 p.m. Kowalsski was studying aerial photographs and shaking his head.

“The German position is too strong,” Kowalsski said without preamble. reinforced stone buildings, interlocking fields of fire. They’ve got Morrison’s men in a basement with one exit. Any relief force loses two men for every yard gained. Hartley studied the photographs. The German command post was visible.

A three-story industrial office building 90 yards behind the forward positions. Officers were observed entering and exiting. Communication cables ran from the building to forward machine gun nests. Stone construction, but wooden floors, windows on all sides. “What if someone got to that command post?” Hartley asked.

Kowalsski looked at him like he’d suggested flying to the moon. “Get to it? How?” You’d have to cross 400 yardds of open ground, bypass three machine gun positions, climb a fence, avoid roving patrols, and somehow enter a building with guards at every door. Then what? You planning to kill every officer inside with your bare hands? Hartley pulled out his crossbow.

Kowalsski stared. Is that a German hunting bow? Hartley nodded. Can you make incendiary devices? Kowalsski blinked. Like grenades? Hartley shook his head. Like fire arrows. Medieval stuff but with modern accelerance. What followed was 2 hours of the strangest weapons development session of the Italian campaign.

Kowalsski, despite his skepticism, was intrigued enough to help. They raided the supply depot for materials. Fabric torn from parachutes. Pine resin used for waterproofing. Motor oil from destroyed vehicles, friction matches, copper wire. Hartley explained the chemistry his father taught him in the mines, how different materials burned at different temperatures, how to create sustained combustion, how to prevent premature ignition.

The design was crude but practical. Wrap the crossbow bolt head in oil soaked fabric. Coat it with pine resin for waterproofing and adhesion. Wire match heads around the impact point. When the bolt struck, friction would ignite the matches. The matches would ignite the oil soaked fabric. The resin would ensure sustained burning.

Temperature would exceed 1200° F. Wooden floors would ignite. Paper would curl and blacken. And in a confined space with vermocked officers in wool uniforms, surrounded by paper maps and wooden furniture, fire would spread faster than men could react. They field tested one arrow at 11 p.m. in a abandoned quarry. The bolt struck a wooden beam. The match head sparked.

Flame erupted. Within 12 seconds, the entire beam was burning. Kowalsski watched the orange glow and said quietly, “You’re actually serious about this?” Hartley loaded another bolt, “Morrison’s got maybe 12 hours before someone dies of dehydration. I’m not asking permission.” Kowalsski was silent for a long moment.

Then the German patrol pattern changes at 2:00 a.m. Shift rotation, 30 minute window of confusion. That’s your best chance. He pulled out a map and began marking positions. Machine gun nest here, here, and here. Roving patrol every 15 minutes along this line. Fence is 6 ft barbed wire top. Command post has guards at the main entrance. Side entrance here appears less guarded. Officers congregate on second floor.

We’ve observed light patterns through windows. Heartley absorbed every detail. Distance to wire, 400 yards across broken ground. Distance from wire to command post. 90 yards through rubble strewn alley. Total approach time estimated 2 to 3 hours moving at infiltration speed.

Mission window 305 minutes before German patrols normalized after shift change. Expected survival rate if discovered 0%. At 11:30 p.m., Hartley returned to his barracks and wrote a letter to his wife. He didn’t seal it. If he came back, he’d destroy it. He checked his gear with mechanical precision.

Wire cutters, combat knife, canteen, compass, six fire arrows wrapped in cloth to prevent damage, the crossbow, morphine ceret in case of capture. He’d heard what the SS did to saboturs. At 11:45 p.m., he left camp through a gap in the perimeter fence he’d discovered weeks earlier. Nobody saw him go.

The night was cold, temperature around 38°, with intermittent clouds obscuring a half moon. Hartley moved through the rubble of Outer Casino like a ghost, using bomb craters for concealment, timing his movements between moonlight and shadow. The ruins smelled of death, unreovered bodies decomposing in collapsed buildings mixed with cordite, smoke, and the peculiar metallic scent of blood soaked earth. Every step required calculation. Broken glass would crunch.

Loose rubble would shift. Movement would draw eyes. He covered the first 200 yards in 40 minutes, reaching the edge of German controlled territory at 12:25 a.m. Here, the approach became lethal. Open ground stretched ahead. A former parking lot now cratered by artillery, but offering minimal concealment.

German flares rose periodically, turning night to day for 30 seconds at a time. Machine gun positions were visible as darker shadows against ruined walls. Search lights swept random patterns, unpredictable and thorough. Hartley went to ground, literally. He lay flat and began crawling using a shallow drainage ditch that ran roughly parallel to his route.

The ditch was 8 in deep, barely enough to conceal a prone man, but sufficient if he moved during darkness, and froze when light came. The frozen mud soaked through his uniform within minutes. His hands went numb within 10 minutes. But the cold was advantage. It suppressed his body heat signature, made his breath less visible, kept him alert through discomfort. At 12:50 a.m., a German patrol passed within 12 ft.

Two soldiers talking in low voices about food and women. The eternal soldiers conversation. Hartley pressed his face into the mud and stopped breathing. Boots crunched gravel. One soldier paused less than 6 ft away. Hartley could smell cigarette smoke. The soldier said something in German. Hartley didn’t speak the language, but recognized the tone.

Observation, not alarm. A rabbit. A shell fragment shifting. The soldier moved on. Hartley waited three full minutes before resuming movement. The barbed wire fence appeared at 1:15 a.m. A dark line against slightly lighter sky. 6 ft tall with three strands of wire across the top, anchored to posts every 10 ft. The wire was new, recently installed based on lack of rust.

Germans were thorough. Hartley pulled out his wire cutters and began the painstaking process of creating a gap. Cut too quickly and the wire would snap with audible twang. Cut too slowly and dawn would catch him exposed. He worked each strand with patience. His father taught him underground.

small cuts, pressure relief, controlled separation. 20 minutes and he had a gap large enough to crawl through. He slipped the cutters back in his belt and began threading his body through the opening. The crossbow and arrows wrapped across his back. The wire snagged his jacket. He froze, worked the fabric free, continued.

His left hand scraped across a barb, drawing blood. He ignored it and pulled himself through to the other side. At 1:40 a.m., Hartley reached the alley that led to the German command post. The building loomed above him, three stories of industrial architecture, built when Casino was a manufacturing town before it became a slaughterhouse. Light showed in second floor windows. Shadows moved against drawn curtains.

Officers reviewing maps, planning tomorrow’s killing. Ground floor showed minimal activity. Side entrance was guarded by a single soldier smoking. His rifle leaning against the wall. The universal posture of the board sentry. Hartley assembled the crossbow in shadows. Hands working by feel. Bolt loaded into channel.

string drawn and locked. He selected the first fire arrow, unwrapped it carefully, examined the match. Head arrangement by moonlight. Everything had to work perfectly once. There were no practice shots in combat. The second floor windows were 25 ft up, roughly 35 yd from his position, within crossbow range. The windows were closed, but the glass was thin.

pre-war commercial grade. The bolt would penetrate. Inside would be wooden floors, paper maps, wool uniforms, and probably a kerosene lamp or two. Everything needed to turn the room into an inferno. At 1:47 a.m., the guard below lit another cigarette. The flare of his lighter illuminated his face for two seconds.

Young, maybe 19, looking tired and cold. Hartley felt a strange sympathy. This kid didn’t choose to be here any more than Morrison’s trapped men did. War put them on opposite sides of weapons. But the kid wasn’t the target. The officers upstairs were. Hartley raised the crossbow, sighted through the crude notch mechanism, compensated for the upward angle and distance. His breath steadied.

His hands were cold but steady. Everything his father taught him about making hard decisions underground crystallized in this moment. You do what needs doing. No hesitation. No second-guing because hesitation kills everyone. He squeezed the trigger at 1:48 a.m.

The crossbow string released with a soft twang, barely audible over ambient night sounds. The bolt flew. 3 seconds of flight time. The bolt struck the second floor window. Glass shattered. The match heads ignited on impact. Orange flame erupted inside the room. For 5 seconds, nothing happened. Hartley was already loading the second arrow, hands moving with practiced speed. Then someone inside screamed.

Not pain, surprise, and alarm. Flames were visible now through the window, spreading faster than he’d calculated, much faster. The pine resin was burning hot, igniting paper on the walls, catching on curtains. The scream became multiple voices, shouting in German. Hartley fired the second bolt into an adjacent window.

More glass breaking, more fire erupting. The room was an inferno within seconds. Flames reaching the ceiling, consuming oxygen, generating heat that cracked more windows. Black smoke poured out into the night air. The guard below dropped his cigarette and stared upward, frozen by confusion.

Was this an air attack? Artillery? Hartley fired the third bolt into the guard’s building entrance, aiming low, hitting the doorframe. The match head sparked. Flames spread across the wooden door, cutting off the entrance, trapping whoever was inside. Now the building was chaos. Officers stumbled into windows, silhouetted against flames, beating at burning uniforms.

One man tried to jump, fell, didn’t get up. Another appeared at a window, fired his pistol blindly into the night. He couldn’t see through the smoke. Couldn’t see anything except his own death approaching. Hartley fired the fourth bolt into a ground floor window where he’d seen movement. The bolt penetrated. Someone inside screamed.

A sound that would haunt. Hartley’s nightmares for decades. The scream cut off abruptly. Fire spread through the ground floor now feeding on wooden furniture, paper documents, creating a chimney effect that sucked flames upward through the building. The fifth bolt went into another second floor window. The sixth into what looked like a communication room based on the antenna wires running to it. Every bolt found its target. Every target became an inferno.

The building was fully engulfed within 3 minutes of the first shot. Flames reaching 30 ft high, visible for miles, turning night into orange day. And then the real chaos began. German soldiers poured from nearby positions, not understanding what was happening, shouting orders that contradicted each other.

Officers stumbled from the burning building. uniforms smoking, trying to direct firefighting efforts that were feudal. There was no water, no equipment, just men beating at flames with coats and blankets. The machine gun positions that had kept Morrison’s men trapped went silent as their crews abandoned posts to respond to the fire.

The interlocking fields of fire collapsed. The carefully coordinated defense disintegrated into running men and confusion. Hartley didn’t watch. He was already moving, dropping back through the alley, crawling toward the factory building where Morrison’s men were trapped. He reached their position at 2:05 a.m.

Hammered on the steel door in the agreed upon pattern. Three fast, too slow, three fast. The door cracked open. Sergeant Eddie Malone’s face appeared, gaunt from dehydration, eyes wide with disbelief. Hartley, what the hell? Move now, Hartley whispered. Germans are distracted. You’ve got maybe 5 minutes. Morrison appeared, skeletal thin, uniform hanging loose.

How? He saw the flames reflected in Hartley’s eyes, and understood. Jesus Christ. You attacked their command post. Burned it. Seven officers dead. Maybe more. Machine gun crews abandoned positions. Route back is clear if you move right now. The 21 survivors stumbled from their prison. Private Chen was unconscious, carried by two stronger men.

Private Kowalsski was barely responsive, supported between two others. They moved like zombies, dehydrated, exhausted, beyond rational thought, but motivated by pure survival instinct. The escape route Hartley had infiltrated through was impassible for 21 exhausted men. He led them instead through the rubble to the west, using the fire’s glow as both distraction and navigation aid. German soldiers were still rushing towards the burning command post.

Nobody was watching the perimeter. Nobody expected an escape attempt during their own catastrophe. They covered 200 yards before the first German officer realized what was happening and screamed orders. Machine gun fire erupted, but it was poorly aimed. The gunners were disoriented, firing at shadows, hitting rubble. Hartley pushed the group into a collapsed building that offered cover. Stay down. Don’t return fire.

Let them waste ammunition. The Germans fired for 2 minutes, hitting nothing. Hartley used the noise to move the group another 50 yards during the confusion. One of Morrison’s sergeants whispered, “You’re crazy, Hartley. Brilliant, but absolutely crazy.” They reached American lines at 2:47 a.m.

, stumbling through the perimeter into the arms of stunned centuries who’d been watching the fire and wondering what the hell happened. Morrison collapsed immediately, unconscious before he hit the ground. Chen was rushed to medical. He’d survived, but lose the leg. Kowalsski would spend 3 weeks recovering from dehydration psychosis. Hartley stood in the aid station at 3:15 a.m.

watching medics work on the rescued men, feeling the adrenaline drain and exhaustion replace it. His hands were shaking. His uniform was caked with frozen mud and blood from a dozen small cuts he hadn’t noticed. The intelligence officer, Kowalsski, appeared with a cup of coffee. Seven dead officers confirmed by radio intercept. The building is still burning.

Germans are calling it a commando raid by a specialist team. They can’t believe one man with a godamn crossbow did this. Morrison was conscious again, taking water in small sips. He looked at Hartley and said quietly, “Why?” It wasn’t an accusation. It was genuine confusion. Hartley thought about answers.

duty, friendship, the simple equation that someone had to act. He said none of those things. Couldn’t listen to you die and do nothing. The immediate aftermath was bureaucratic chaos. The battalion commander wanted to court Marshall Hartley for leaving his post without orders.

The division commander wanted to give him a medal for saving 21 men and destroying a German command node. The intelligence section wanted to document his methods for potential replication. The OSS sent an observer who spent 2 hours interviewing Hartley about improvised incendiary devices. Witness statements were filed within 48 hours. Morrison wrote, “Sergeant Hartley conducted a solo infiltration mission under impossible odds and executed an assault that achieved complete tactical surprise.

His actions directly resulted in the survival of 21 American soldiers who would otherwise have died in captivity. 15 other soldiers provided similar statements. The German radio traffic intercepted and translated confirmed seven officer deaths, including a battalion commander with the command post and all its communication equipment destroyed. Hartley was recommended for the distinguished service cross.

The award was downgraded to a silver star due to irregular nature of mission authorization. He received it 3 weeks later in a brief ceremony where the division commander shook his hand and said, “Don’t ever do anything that stupid again.” Hartley promised nothing. The freed prisoners had varied fates.

Captain Morrison returned to duty within a week, led his company through the remainder of the Italian campaign, and survived the war. He returned to his law practice in Pennsylvania and named his son William after Hartley. Private Chen lost his leg but survived, returned to San Francisco, married his high school sweetheart, raised four children.

He kept Hartley’s photograph on his desk for the rest of his life. Private Kowalsski recovered from dehydration psychosis, returned to Detroit, worked in the auto factories, and attended every 36th Infantry Division reunion until his death in 1987. The mission’s impact extended beyond the individual men saved. Army intelligence documented Hartley’s improvised incendiary technique.

OSS field manuals added sections on expedient fire weapons. Three similar missions were attempted in subsequent months. Two succeeded, one failed when the infiltrator was discovered before reaching his target. The Germans, for their part, reinforced command post security throughout their Italian positions, added fire suppression equipment, and issued orders against wooden construction in tactical headquarters. Hartley survived the war.

He fought through the rest of the Italian campaign, crossed into southern France during Operation Dragoon, entered Germany in early 1945. He was in Bavaria when the war ended, aged 29. Somehow still alive when so many weren’t. He returned to Beckley in July 1945, walked into his house, picked up his daughter, who didn’t recognize him, and held her for an hour without speaking. He didn’t return to the mines.

The war had shown him enough darkness. He used his GI build to learn carpentry, opened a small furniture shop that specialized in custom cabinets. The work was honest, quiet, creative in ways that mining never was. He rarely spoke about the war. When neighbors asked, he deflected. Did what everyone did. Nothing special.

But every March 14th, his phone rang. Morrison calling from Pennsylvania. Chen calling from San Francisco. Kowalsski calling from Detroit. Other voices. men who’d been in that factory basement watching their friends die of thirst until fire lit the night and salvation appeared in the form of a West Virginia coal miner with a medieval weapon and no respect for probability.

Hartley died in 1983 age 67 of heart failure. The funeral in Beckley drew more than 200 people. Morrison traveled from Pennsylvania to deliver the eulogy. Chen came in a wheelchair from California. Kowalsski’s son attended. His father had died the year before, but made his son promise to represent him. 15 other men from the 36th Infantry Division attended. Old soldiers in their 60s.

Standing in the cold rain to honor the man who proved that impossible was just another word for difficult. Morrison’s eulogy was simple. Bill Hartley taught me that courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s the decision that something else matters more. In his case, it was simple. He couldn’t let us die. That choice saved 21 lives. It saved mine.

He went home after the war and built furniture and raised a family and never once claimed to be a hero. But heroes are defined by actions, not words. And Bill’s actions spoke clearly enough. The rescued prisoners created a legacy of quiet gratitude. Chen’s children learned their father’s survival story and understood why he kept that photograph on his desk.

Morrison’s son, William, became a firefighter, drawn to emergency service by stories of desperate rescue. Kowalsski’s grandson wrote a college thesis on improvised tactics in World War II, using his grandfather’s experience as primary source material. Military historians have analyzed Hartley’s mission in the decades since.

The consensus it was tactically reckless, strategically unnecessary, and succeeded only through a combination of skill, desperation, and extraordinary luck. A similar mission attempted by special forces under controlled conditions had a projected success rate of approximately 15%. Hartley succeeded where trained commandos might have failed because he didn’t approach it as a military operation. He approached it as a mining problem.

Identify the structural weakness, exploit it with available tools, and don’t overthink the solution. The fire arrow crossbow itself exists now in the 36th Infantry Division Museum in Texas, preserved behind glass alongside Hartley’s Silver Star Citation and photographs of the burned German command post taken after Casino’s capture.

Visitors often ask if the story is real. Museum dosent point to the witness statements, the afteraction reports, the German radio intercepts, the testimony of 21 men who were hours from death until a man they barely knew decided their lives were worth his. Modern military doctrine includes sections on improvised weapons and expedient tactics influenced in part by missions like Hartley’s.

Special forces train on historical examples of successful desperate actions. The lesson isn’t to encourage reckless heroism. It’s to understand that sometimes the impossible becomes possible when someone refuses to accept that designation. If you found this story of desperate innovation and impossible odds compelling, please like this video.

Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories of ordinary men who accomplished extraordinary things. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from. Thank you for keeping these stories