December 3rd, 1944. Herken Forest, Germany. The German machine gunner from the 326th Vulks Grenadier Division lined up his MG42 on the advancing American infantry. At 400 m, he squeezed the trigger, sending a burst of 7.92 mm rounds down range at,200 rounds per minute. Through his scope, he watched the impacts strike an American soldier square in the chest.

The soldier stumbled backward, fell to one knee, then impossibly stood back up, and continued advancing. The German gunner blinked in disbelief. He had seen the rounds hit center mass. At this range, those bullets should have torn through the soldier’s body.

Yet, the American was not only alive, but still fighting. What the German machine gunner could not have known was that beneath that soldier’s uniform lay something the Vermach had dismissed as the desperate improvisation of a losing army. Layers of laminated plywood precisely angled and carefully constructed that would revolutionize battlefield protection and save thousands of American lives. This is the story of how ridicule turned to respect.

how desperation bred innovation and how wooden armor became one of World War II’s most underestimated advantages. The crisis began in the summer of 1944. American forces advancing through France were sustaining casualty rates that shocked commanders and terrified soldiers.

Small arms fire, particularly from German machine guns and rifles, accounted for 63% of all combat wounds. Unlike artillery fragments that often caused superficial damage, rifle bullets killed with horrifying efficiency, a single 7.92 mm mouser round could penetrate 4 in of flesh, shattering bone and destroying vital organs.

At forward aid stations, medics recorded grim statistics. Chest wounds had an 82% fatality rate. Abdominal wounds killed 91% of victims. Soldiers hit center mass rarely survived long enough to reach surgical hospitals. The mathematics were brutal and undeniable. Without protection, advancing infantry were simply targets waiting to be hit. The United States Army had recognized the body armor problem years earlier.

In 1942, the Army Technical Division began testing various protective systems. They evaluated steel plates, but found them too heavy. A vest capable of stopping rifle rounds weighed over 40 lb, exhausting soldiers before they reached combat. They tested aluminum alloys, but these were needed desperately for aircraft production.

They experimented with layers of canvas and resin, but these provided inadequate protection against high velocity rifle rounds. By mid1 1944, the official solution remained the M1944 armored vest, primarily designed to stop artillery fragments. This vest, made of overlapping manganese steel plates, weighed 12 lbs and provided excellent protection against shrapnel.

But against direct rifle fire at combat ranges, it was nearly useless. German 7.92 millimeter rounds punched through it like paper. Soldiers knew this. They had watched friends die wearing the official armor. Trust in armyisssued protection had collapsed. Men were improvising their own solutions.

Stuffing magazines inside their jackets, wearing extra layers of uniforms, even carrying metal plates scavenged from destroyed vehicles. None of it worked. The desperation was palpable. Private First Class James Morrison of the 28th Infantry Division had a different idea. Morrison, a carpenter from Portland, Oregon, before the war, understood wood in ways most soldiers did not.

He knew that different woods had different properties. He understood grain direction, compression strength, and lamination principles. Most importantly, he had seen something during training that everyone else had dismissed. In August 1944, during a demolition exercise, Morrison watched engineers trying to destroy a wooden bunker with small arms fire.

The bunker, constructed from laminated plywood sheets, absorbed hundreds of rounds before finally splintering. The bullets penetrated but slowly, losing velocity as they traveled through successive layers. Morrison stood watching, calculating, thinking. That night, he sketched designs in his notebook.

Multiple layers of 1/4in plywood, grain directions alternating at 90° to each other, curved to fit the torso, angled to deflect rather than absorb impacts. The concept was simple. Wood fibers were incredibly strong along the grain. A bullet hitting perpendicular to the grain had to sever thousands of individual fibers. By layering wood with alternating grain directions, he could force a bullet to cut through fibers from multiple angles, dissipating its energy. Morrison screded materials from a demolished French farmhouse.

He found sheets of birch plywood, salvaged glue from a carpenters’s shop, and borrowed tools from the engineering company. Working at night by candle light, he constructed his first vest. Eight layers of quarterinch plywood, each layer glued and pressed. The total thickness was 2 in. The weight was 7 lb, 5 lb lighter than the steel vest. The construction took three nights.

His squadmates mocked him mercilessly. Corporal William Baker called it Morrison’s wooden coffin. Sergeant Thomas Henley said he looked like a walking crate. Private Robert Chen joked that Morrison should paint targets on it to help the Germans aim. The ridicule was constant and cruel. Even Lieutenant James Phelps, their platoon leader, expressed skepticism.

Morrison, that contraption will get you killed. Wood can’t stop bullets. You’re wasting your time. But Morrison persisted. He understood something the mockers did not. kinetic energy dissipation. A bullet’s destructive power came from its velocity. Anything that slowed the bullet reduced its lethality.

Steel stopped bullets through hardness, forcing them to deform or shatter. Wood stopped bullets through absorption, capturing them in layers of fiber that compressed and deformed, converting kinetic energy into heat and structural damage. Morrison’s calculations suggested that 2 in of properly laminated hardwood could stop a 7.92 mm round at ranges beyond 200 m.

At closer ranges, the wood would slow the bullet enough to prevent fatal penetration. It would not stop everything, but it might stop enough. In a war where survival often came down to inches and seconds, that might was worth testing. The first test came on September 19th, 1944 during the assault on the Sief Freed line fortifications.

Morrison’s company, Company B of the 110th Infantry Regiment, received orders to clear German bunkers near the Belgian German border. The attack began at 0600 hours with artillery preparation. At 0630, infantry advanced across open ground toward fortified positions. German machine guns opened fire at 400 meters.

The distinctive sound of MG42s filled the air, firing at rates that turned individual shots into continuous roars. Morrison, wearing his wooden vest beneath his uniform, advanced with his squad. Bullets cracked past, striking soldiers around him. Private David Foster, 10 ft to Morrison’s left, fell with a chest wound.

Corporal Baker, who had mocked Morrison’s vest days earlier, went down with stomach wounds. Then Morrison felt the impact. A hammer blow to his chest that knocked him backward. He fell. The wind knocked from his lungs. For several seconds, he could not breathe, could not think. His chest felt crushed. When his vision cleared and his breathing returned, Morrison realized he was alive. He stood up, checked himself.

No blood, no penetration. The bullet had hit his wooden vest and stopped. The rest of the attack passed in a blur. Morrison continued fighting, reaching the German positions, clearing bunkers, but his mind was on the vest. It had worked. The impossible had happened. Wood had stopped a German bullet.

After the attack, Morrison removed the vest and examined it. The impact point was obvious. A crater approximately 1 inch deep and 2 in in diameter. The bullet, a 7.92 millimeter mouser round, was embedded in the sixth layer of plywood. It had penetrated five layers, each one slowing it before the sixth layer stopped it completely.

Morrison brought the vest to Lieutenant Phelps along with the extracted bullet. Phelps examined both in silence. He measured the penetration depth, studied the deformation pattern, tested the vest’s structural integrity. Finally, he looked at Morrison and said, “How many more of these can you make?” Word spread through the 28th Infantry Division with remarkable speed.

Within days, soldiers were approaching Morrison, requesting wooden vests. He could not possibly meet the demand alone, but he did not have to. Other soldiers with woodworking skills began constructing their own versions. Private Leo Kowalsski, a Polish immigrant who had worked in a furniture factory, improved Morrison’s design by adding shoulder protection.

Sergeant Frank Sullivan, a former shipwright, developed curved panels that provided better side coverage. By early October 1944, approximately 200 soldiers in the 28th Infantry Division were wearing improvised wooden armor. The designs varied. Some used oak, others birch or maple. Some incorporated eight layers, others 10.

Some added leather straps for comfort, others used canvas. But the principle remained constant. Multiple layers of hardwood with alternating grain directions. designed to absorb and dissipate bullet energy. German intelligence noticed something unusual during interrogations of American prisoners. Multiple captives wore crude wooden panels under their uniforms.

When questioned, these prisoners explained that the wood was personal armor constructed because official army armor was inadequate. German interrogators recorded this information with a mixture of curiosity and contempt. The Americans were so desperate they were wearing wood as armor.

A report filed by the 326th Vulks Grenadier Division to Fifth Panzer Army headquarters in October 1944 stated, “American Infantry increasingly employs improvised protective equipment, including wooden panels worn as body armor. This improvisation suggests serious deficiencies in American military supply systems. Troops appear to have lost confidence in official equipment.

Assessment indicate declining morale and increasing desperation. The German analysis could not have been more wrong. The wooden armor represented American innovation at its most practical. Soldiers identified a problem, developed a solution, and implemented it without waiting for official approval or support. This bottom-up innovation, characteristic of democratic armies, created battlefield advantages that top-down authoritarian systems could not match. The wooden armor’s effectiveness became undeniable during the battle of Schmidt in November

- The 28th Infantry Division, tasked with capturing the town of Schmidt in the Herkin Forest, faced some of the most intense combat of the European campaign. German defenders dug into fortified positions had clear fields of fire across open areas that American infantry had to cross.

During the November 2nd attack, Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment advanced across a killing zone swept by machine gun fire from three positions. The company, 143 men at the start, suffered catastrophic casualties. 91 men were hit by small arms fire. Of those 91, 63 died. But among the 28 who wore wooden armor, the survival rate was dramatically different.

18 were hit by bullets that struck their wooden vests. 15 survived their wounds. Three died from hits to unprotected areas. The statistics were impossible to ignore. Soldiers wearing wooden armor had a 54% survival rate when hit. Soldiers without it had a 30% survival rate. The difference, 24 percentage points, translated directly into lives saved.

If the entire company had worn wooden armor, approximately 21 additional men might have survived. These numbers reached Major General Norman Cota, commanding the 28th Infantry Division. Cota, a aggressive commander who had led troops ashore at Omaha Beach, understood battlefield innovation. He immediately authorized divisional resources to support wooden armor production.

The division’s engineer battalion established workshops. Carpenters were pulled from other duties. Wood was requisitioned from French sawmills and German lumber yards. Glue was obtained through quartermaster channels. By mid- November 1944, the 28th Infantry Division was producing approximately 50 wooden vests daily.

The engineering battalion standardized to the design based on Morrison’s original pattern with improvements from multiple contributors. The standard vest consisted of nine layers of quarterinch birch or maple plywood. Total thickness 2.25 in. Weight 7.5 lb. coverage from shoulders to waist with cutouts for arms and neck.

Testing conducted by the division revealed impressive performance against 7.92 mm Mouser rounds at 300 m. Full stop, no penetration. At 200 m, full stop, no penetration. At 100 m, penetration to seventh layer, bullet stopped. at 50 m full penetration but bullet velocity reduced by estimated 60%. If you’re finding the story as fascinating as we are, please take a moment to subscribe to our channel and hit the notification bell.

We bring you untold stories from history every week and your subscription helps us continue this important work. Now, let’s continue with how this wooden armor changed everything. The improved survival rates had profound psychological effects. Soldiers wearing wooden armor reported feeling more confident during advances.

They took fewer unnecessary risks, but maintained better tactical discipline. The knowledge that they had some protection, even imperfect protection, reduced the paralyzing fear that led to fatal hesitation. Company commanders noticed that units with higher percentages of wooden armored soldiers sustained attacks longer and achieved objectives more frequently.

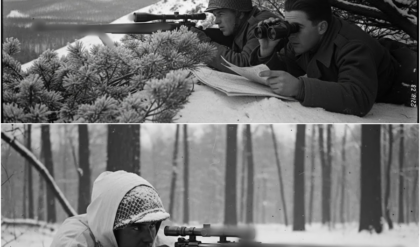

German forces, meanwhile, struggled to understand what they were encountering. Machine gunners reported firing center mass at American infantry and watching them continue fighting. Snipers observed hits that should have been kills, but resulted only in soldiers stumbling and recovering. German combat reports from December 1944 increasingly mentioned American infantry who appeared resistant to small arms fire.

A captured American soldier wearing wooden armor provided German intelligence with their first detailed examination of the system. The soldier, Private Harold Webster of the 109th Infantry Regiment, was captured on November 28th near Commershite. German interrogators photographed his vest, measured its dimensions, and conducted ballistic tests.

Their report, classified gahim, secret, and distributed to army group commanders, concluded, “American improvised wooden armor demonstrates surprising effectiveness against small arms fire at combat ranges. Construction is crude but functional. Materials are readily available. Production requires minimal industrial capacity.

If widely adopted, this system could significantly reduce American casualties from small arms fire, potentially extending American offensive capability. Recommend development of counter measures, but Germany in late 1944 had no resources for counter measures. The Vermacht was fighting for survival on multiple fronts.

The suggestion that they develop new ammunition or tactics to counter wooden armor was impractical to the point of absurdity. The report was filed and largely forgotten. Meanwhile, American soldiers continued wearing wood and surviving. News of the 28th Infantry Division’s wooden armor reached higher headquarters through medical channels.

Forward surgical hospitals noticed that soldiers from the 28th had unusual wound patterns. Bullets that struck the chest or abdomen often caused severe bruising and possible rib fractures, but did not penetrate body cavities. The wooden armor was creating a new category of injury, severe impact trauma without penetration.

Captain Robert Harrison, a surgeon with the 45th Field Hospital, documented these cases in his medical reports. He noted that soldiers with wooden armor injuries had dramatically better survival rates than those with penetrating wounds. His reports reached the office of the surgeon general in Washington, which forwarded them to the Army Technical Division.

In January 1945, a team of engineers and medical officers visited the 28th Infantry Division to examine the wooden armor firsthand. The team included Major William Davis from the technical division, Captain Thomas Reynolds from the Surgeon General’s office, and civilian engineer Dr. Robert Mitchell from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

They interviewed soldiers, examined vests, conducted ballistic tests, and compiled comprehensive performance data. Their report submitted in February 1945 recommended immediate adoption of wooden armor as an interim solution until improved body armor could be developed. The report noted improvised wooden armor constructed by 28th Infantry Division personnel demonstrates effectiveness comparable to or exceeding official M1944 armored vest against small arms fire.

weight is lower, comfort is greater, and soldier acceptance is significantly higher. Recommend authorization for theaterwide production and distribution. The recommendation faced immediate opposition from army ordinance. Brigadier General Thomas Hayes, head of the small arms division, argued that authorizing wooden armor would undermine confidence in official equipment.

He claimed that wooden armor was unscientific, unreliable, and potentially dangerous if soldiers relied on inadequate protection. His position reflected institutional resistance to bottom-up innovation and soldier developed solutions. But General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, overruled the objections.

Eisenhower, informed of the wooden armor’s effectiveness and the soldier support for it, issued a directive in March 1945 authorizing theater level production of wooden body armor. The directive stated, “Theater commanders are authorized to establish production facilities for wooden body armor based on designs developed by 28th Infantry Division. Distribution priority to infantry units in direct combat.

production to continue until improved body armor becomes available. The authorization transformed wooden armor from improvised solution to official equipment. Engineer battalions throughout the European theater established workshops. Civilian contractors in liberated France and Belgium received contracts for vest production.

German lumber from captured stockpiles was diverted to armor production. By April 1945, production reached approximately 800 vests daily across the theater. The standardized production model incorporated several improvements over the original field expedient versions. Engineers developed better glues that maintained bonding under wet conditions.

They created foam padding that reduced impact trauma. They designed adjustable strap systems that accommodated different body sizes. They added canvas covers that protected the wood from moisture and provided camouflage. The production model weighed 8.2 lb, provided coverage for chest, abdomen, and back, and cost approximately $7 to manufacture.

Distribution prioritized infantry divisions in heavy combat. The fourth infantry division fighting through the Herkin forest received 2,000 vests in March. The first infantry division advancing into Germany received 1,500 vests in early April. The 9inth infantry division crossing the Rine received 1,200 vests.

By war’s end in May 1945, approximately 23,000 wooden armor vests had been produced and distributed. Casualty statistics from units equipped with wooden armor showed measurable improvements. The Fourth Infantry Division, which suffered horrific casualties in the Herkin Forest, reported a 16% reduction in small arms fatalities after receiving wooden armor in March.

The First Infantry Division reported a 12% reduction. The 9inth Infantry Division reported a 19% reduction. These percentages translated into thousands of American lives saved. German prisoners of war interrogated in April and May 1945 consistently mentioned American wooden armor. Leiton Hans Mueller of the 276th Vulks Grenadier Division testified, “The Americans wear wooden plates under their uniforms.

We were told to aim for the head, but this is very difficult in combat conditions. Many soldiers reported hitting Americans in the body and watching them continue fighting. It was demoralizing. The psychological impact on German forces proved as significant as the physical protection. German infantry already demoralized by overwhelming Allied material superiority now faced enemies who seemed resistant to bullets.

Combined with American advantages in artillery, air support, and armor, the wooden body armor contributed to a sense of hopelessness among German troops. They were fighting an enemy who had more of everything and who could even make effective armor from trees. Private first class James Morrison, the carpenter from Portland who had constructed the first vest, survived the war. He participated in the occupation of Germany and returned to the United States in December 1945.

He brought his original wooden vest home, the one that had stopped a German bullet on September 19th, 1944. That vest is now part of the collection at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans. In a 1986 interview, Morrison reflected on his invention. I wasn’t trying to revolutionize anything.

I just wanted to survive. I saw a problem. I had skills that could address it. And I tried. The fact that it worked and helped other guys survive, that’s what I’m proud of. Not the invention itself, but the lives it saved. I think about the guys who didn’t make it. And I wonder if wooden armor could have saved them.

That’s what keeps me up at night. The wooden armor story reveals several truths about World War II that challenge popular narratives. First, American soldiers were not simply well-supplied automatons following orders. They were innovative problem solvers who identified deficiencies and developed solutions. Second, official military equipment was not always superior to improvised alternatives.

Sometimes the best solution came from the front lines, not from laboratories. Third, the US military’s willingness to adopt soldier developed innovations represented a fundamental advantage over more rigid authoritarian militaries. The German response to wooden armor illustrated vermach limitations in late war period. Facing a simple but effective innovation, German forces had no resources to develop counter measures.

They could document the problem, analyze it, and report it, but they could not address it. The industrial and logistical capacity for adaptation had been exhausted. Meanwhile, American forces could mass-produce wooden armor using readily available materials and distribute it within weeks. Postwar analysis by Army Ordinance revealed that wooden armor had been more effective than anyone expected.

Testing conducted in 1946 and 1947 showed that properly constructed laminated plywood armor actually outperformed contemporary steel armor of equal weight. The wood’s ability to absorb and dissipate energy through compression and fiber separation proved more effective than steel’s brittle failure mode. This discovery influenced post-war body armor development.

The modern Kevlar vest introduced in the 1970s uses a conceptually similar approach. Multiple layers of strong fibers oriented in different directions designed to catch and slow bullets through fiber interaction rather than brittle hardness. The principle that Morrison stumbled upon in 1944 became the foundation for modern softbody armor.

The wooden armor story also highlights the human cost of equipment deficiencies. The M1944 armored vest, while excellent against shrapnel, was inadequate against rifle fire. Soldiers knew this and sought their own solutions. The fact that improvised wooden armor saved thousands of lives raises uncomfortable questions about how many lives could have been saved if the military had recognized the rifle fire protection problem earlier and developed official solutions.

Captain Robert Harrison, the surgeon who documented wooden armor injuries, estimated in his post-war writings that widespread adoption of wooden armor in summer 1944 rather than spring 1945 could have saved approximately 3,000 American lives. This estimate based on casualty statistics and wounded tokilled ratios suggests that bureaucratic delays in accepting soldier innovations had measurable costs in American blood.

The broader lesson extends beyond World War II. Military organizations by nature hierarchical and procedur often resist bottom-up innovation. The wooden armor case demonstrates that some of the most effective solutions come from those closest to the problems, the soldiers in combat. Creating systems that recognize, evaluate, and rapidly adopt soldier innovations represents a strategic advantage that can save lives and improve combat effectiveness.

German military culture with its emphasis on following established procedures and respecting technical authority was particularly ills suited to the kind of improvisation that Morrison exemplified. Vermached soldiers who developed innovative solutions faced skepticism from superiors and rigid adherence to official doctrine.

American military culture, while far from perfect, proved more receptive to unconventional ideas that demonstrabably worked. By May 1945, when Germany surrendered, wooden armor had become a standard part of US infantry equipment. Soldiers wore it without mockery or shame. It was simply another tool that helped them survive. The transformation from Morrison’s wooden coffin to officially sanctioned life-saving equipment had taken just 8 months. A remarkably rapid adoption for military bureaucracy.

The postwar demobilization led to the destruction of most wooden armor vests. They were bulky, difficult to transport, and considered obsolete with the war’s end. Of the approximately 23,000 vests produced, fewer than 100 survive in museum collections today, most were simply discarded or burned.

This disposal erased physical evidence of one of the war’s more unusual innovations. Veterans who had worn wooden armor rarely discussed it after the war. Unlike combat decorations or unit histories, body armor was not something men boasted about. It was a practical tool, nothing more. The lack of post-war publicity meant that the wooden armor story remained largely unknown outside specialist military history circles. Even today, most World War II enthusiasts have never heard of it.

The few veterans who did discuss their experiences universally expressed gratitude for Morrison’s innovation. Corporal William Baker, who had mockingly called Morrison’s first vest a wooden coffin, wore wooden armor during the final months of the war. In a 1992 letter to Morrison, Baker wrote, “I was an idiot for making fun of your vest. You were right and I was wrong.

I wore one of those vests during the push into Germany and I believe it saved my life. I took a hit near Remigan that would have killed me without that wood. I owe you everything. Thank you. Morrison kept that letter until his death in 2003 at age 82. His family donated his papers, including the letter and his original design sketches, to the Oregon Historical Society.

Researchers studying his documents discovered that Morrison had continued refining his wooden armor concept after the war, sketching designs for improved versions and calculating performance specifications. He never pursued commercial production, but he never stopped thinking about how to better protect soldiers.

The wooden armor story challenges simplistic narratives about World War II as a conflict decided purely by industrial production and firepower. Yes, America’s massive industrial capacity was decisive. Yes, Allied material superiority overwhelmed Axis forces, but within that larger story existed countless smaller innovations like wooden armor that provided tactical advantages and saved individual lives.

These innovations developed by ordinary soldiers using ordinary materials, accumulated into strategic advantages. If you’ve made it this far, you clearly appreciate deep dives into forgotten history. We’d love to have you as a regular viewer. So, please subscribe and share this video with anyone who loves untold stories from the past.

Your support means everything. Now, let’s wrap up this remarkable story. The mockery that Morrison endured in August 1944 represented a common human response to unconventional ideas. His squadmates, facing death daily, could not afford to believe in unproven solutions. Skepticism protected them from false hope.

But Morrison’s willingness to persist despite mockery, to test his idea despite ridicule, to prove effectiveness through demonstration rather than argument, exemplify the innovation that democratic societies enable. Totalitarian regimes, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan could marshall industrial resources and enforce military discipline, but they struggled to accommodate bottom-up innovation that challenged official doctrine.

The Vermacht’s response to wooden armor, dismissing it as evidence of American desperation rather than recognizing it as effective innovation, revealed institutional blindness that contributed to German defeat. They could not imagine that a simple solution developed by a carpenter could outperform products of German engineering expertise. The final irony emerged in captured German documents examined after the war.

In March 1945, a German research facility had begun experiments with laminated wood armor for aircraft. They discovered that properly constructed plywood could provide protection comparable to light armor plate at significantly reduced weight. The research never progressed beyond initial testing due to Germany’s collapse, but it confirmed what Morrison had proven in combat. Wood could stop bullets.

Had Germany recognized wooden armor’s potential when they first encountered it in October 1944, they might have equipped their own infantry with similar protection. German soldiers suffering horrific casualties as they retreated toward the Reich desperately needed any protective advantage.

But the Vermach’s institutional arrogance and rigid adherence to official doctrine prevented them from learning from enemy innovations. They mocked wooden armor even as it killed them. The wooden armor legacy extends to modern military equipment in unexpected ways. The concept of layered protection using materials that absorb and dissipate energy rather than simply resisting it influenced the development of composite armors, spall liners, and soft body armor. Modern soldier protection systems owe conceptual debt to a carpenter from

Portland who refused to accept that official equipment was the only solution. Private first class James Morrison never received official recognition for his innovation. He was not awarded medals, not promoted for his contribution, not even mentioned in official histories until decades after the war.

The army, embarrassed that a private soldier had developed better armor than its engineers, preferred to minimize the wooden armor story. Morrison did not care. He had survived, helped others survive, and returned home to his family. That was recognition enough. The soldiers who wore wooden armor and survived because of it carried their own recognition. They knew what had saved them.

In veteran reunions, in letters to each other, in quiet conversations with their children, they told the story of the carpenter who made armor from trees. These personal histories passed down through families preserve the memory when official records did not. Today, historians studying World War II innovation increasingly recognize the wooden armor story as exemplifying American military strengths.

The ability to identify problems, develop solutions, test them in combat, and rapidly scale successful innovations represented advantages that no amount of German technical sophistication could overcome. Morrison’s vest, crude and simple as it was, saved more American lives than many far more sophisticated weapon systems. The transformation from mockery to respect took just weeks.

Morrison’s wooden coffin became life-saving equipment because it worked. In war, effectiveness trumps elegance. Soldiers care about survival, not sophistication. The wooden armor’s crudeness was irrelevant. Its functionality was everything. German soldiers trained to respect technical perfection and engineering excellence could not understand how something so simple could be so effective.

This incomprehension extended throughout German military culture. German generals educated in prestigious militarymies and steeped in traditional doctrine could not adapt to an enemy that valued practical effectiveness over theoretical purity. American soldiers, many of them civilians in uniform, brought civilian problem-solving approaches to military challenges. They tried things, failed, adjusted, and tried again.

This iterative approach, common in American industry and business, proved devastatingly effective in war. The wooden armor story ends not with triumph, but with quiet effectiveness. By war’s end, thousands of American soldiers were alive because a carpenter from Portland had an idea and the courage to test it.

They returned home, raised families, built careers, and lived lives that would have ended in French or German forests without two inches of laminated plywood. Their survival, mundane and unmarked, was Morrison’s true legacy. In 2019, the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command published a research paper examining historical innovations in soldier protection.

The paper included a section on World War II wooden armor, noting its surprising effectiveness and the valuable lesson it provided. Never dismiss simple solutions without testing. Sometimes the best answer comes not from laboratories, but from battlefields, not from engineers, but from soldiers, not from theory, but from desperate necessity.

They mocked his stupid wooden armor until it stopped a German bullet. Then they stopped mocking and started copying. In 8 months, wooden armor went from one soldier’s ridiculous idea to official equipment worn by thousands. The transformation represented American innovation at its most characteristic, practical, rapid, and effective.

It proved that in war, as in life, the best solution is often the one that simply works, regardless of how stupid it looks to those who have never tested it. Morrison’s vest hangs in a museum now, a crude assembly of wood and glue that saved a life and inspired thousands of copies. Visitors walk past it without recognition, seeing just another artifact from a war long ended.

But for those who know the story, that vest represents something profound. The power of individual innovation, the importance of testing unconventional ideas, and the truth that sometimes the best armor against mockery is simply being right. The German machine gunner who watched his bullets stop against wooden armor probably never knew what he was shooting at.

He saw only an American soldier who should have fallen but did not. That soldier, protected by layers of plywood that German doctrine said could not work, survived to tell a story. A story about how desperation and creativity defeated ridicule and convention. A story about how wood, the most ancient of human materials, stopped German steel, the most modern of weapons.

A story that reminds us that in war, as in innovation, never assume something cannot work until you have proven it cannot. Sometimes stupid ideas turn out to be brilliant. Sometimes mockery turns to respect. Sometimes wooden armor stops bullets and lives are saved by believing the impossible might just be possible.