The basin of water steams in the December cold. Ernst Bower’s blackened toes, all 10 of them disappear beneath the surface, and the pain that follows makes him scream. Not the dignified silence of a vermached soldier. A raw animal scream that echoes off the canvas walls of the American field hospital. Keep them under, the American doctor says, his hands steady, gentle.

Hold Ern’s ankle beneath the waterline. I know it hurts. That is how we know there is still something to save. Still something to save. Ernst’s mind cannot reconcile those words with the reality. 6 in from his face, his feet are dead. The flesh turned white, then modeled red, then black as frozen meat over 3 days in a foxhole outside Bastoni.

The German medic had been clear. When you get back to our lines, they will amputate both feet, maybe higher. But Erns did not make it back to German lines. And now this American, this captain with careful hands and an impossible claim is telling him something different. Something that violates everything Erns knows about frostbite treatment.

German protocol is absolute. Black tissue is dead tissue. Amputate immediately. Clean cuts. Quick recoveries. Why are you not cutting? Ernst asks in broken English, then German, then a desperate mix of both. The American doctor, Captain James Patterson, mid-40s, graying at the temples, looks up. His eyes are bloodshot from 72 hours without sleep.

But they are focused, present, because I do not think we need to. That answer makes no sense. Any German surgeon would have him on the table already, saw in hand. Ernst has seen it done a dozen times. The pragmatic efficiency of German military medicine. Amputate the dead. Save the living.

But this American is running warm water over tissue that looks like charred wood and claiming he can save it. In 40 years, Ernst Bower would perform over 10,000 surgeries. Every single one of them standing on feet an American doctor refused to amputate. 3 weeks earlier, Ernst Bower had been a perfectly ordinary soldier in a perfectly desperate situation.

23 years old. Medical student from Hamburg before the war pulled him out of second year. His father had been a surgeon with steady hands qualities Ernst inherited along with wireframe glasses now held together with electrical tape. He had been assigned to the 26th Vulks Grenadier Division in late November. Green troops, old men, equipment held together with hope and wire.

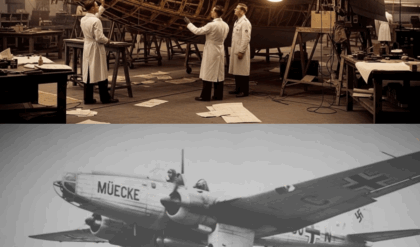

Their winter clothing was designed for a war that was supposed to have ended 3 years ago, but they had propaganda. Erns still remembered the poster in the barracks, a grotesque caricature of an American soldier, ape-like, drooling, blood dripped hands, bold Gothic script below. Dur Americanish barber see Kenan Kyn nade the American barbarian.

They know no mercy. The training sergeant had been specific. They do not follow the Geneva Convention like we do. They will torture you for information then shoot you in a ditch. Better to die fighting than surrender to the Americans. Ernst had believed him. Why would he not? He had seen the burned out vehicles, the cratered towns, the reports of terror bombing campaigns.

If Americans would do that from the sky, what would they do face to face? His father had written him one letter before mail service failed. Ernst kept it in his breast pocket. Remember, you are a bower. We serve life, not death. Come home with your hands clean so you can do that work. Then came the Arden’s offensive. The shocking initial success.

The slow realization that success was temporary and winter was permanent. The cold came first, then the American counterattack, then the foxhole. Ernst and two others scraped out a depression behind a destroyed tank near Bastoni. They were supposed to hold until reinforcements arrived. The reinforcements never came.

American artillery did. For 3 days, they stayed underground. The temperature dropped to minus20 C. On the second day, Erns noticed his feet felt warm. That is when he knew they were dying. Frostbite does not hurt at first. That is the trick. The warmth is an illusion. Death disguised as comfort.

By the third day, he could not feel his feet at all. When he pulled off his boots, a mistake, his socks came away with patches of frozen skin attached. The flesh underneath was white, waxy, dead. Müller looked at Ernst’s feet and crossed himself. “Can you walk?” Klene asked. Ernst tried. He made it three steps before collapsing.

That is when the Americans came. They did not come like the propaganda said they would. No war cries, no bayonets, no barbarian cruelty, just quiet voices in accented German. Hendai hulk, hands up. Ernst raised his hands from where he lay in the frozen mud, waiting for the gunshots, for the torture, for the things the sergeant had described.

An American soldier, a kid, 19 at most, knelt beside him. “You hit?” he asked in broken German. Ernst shook his head, pointed at his feet. The kid’s face registered pity. He called over his shoulder. Sarge got one with bad frostbite. The sergeant who appeared assessed Ern’s feet with professional detachment. Can he walk? No, Sarge.

Right. Get him on a stretcher. We will send him back with the next batch of wounded. We will send him back. Not shoot him. Not leave him. Send him back. Ern’s brain struggled to process this. They were treating him like a wounded soldier who deserved medical care. That was not what he had been told. They loaded him on a stretcher alongside an American with a gut wound.

The American looked over at Ernst, enemy soldier, cause of his suffering, and said something Ernst did not understand. Not angry, almost conversational. The medic glanced back. He says you look like He says he hopes the docs can help you. Ernst could not respond. The cognitive dissonance was too great. The field hospital was chaos, organized by exhaustion.

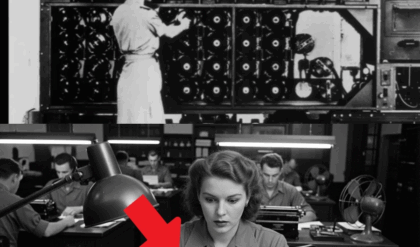

Canvas tents stained with mud and blood. The metallic smell mixing with disinfectant. Doctors and nurses moving with efficient urgency beyond human limits. American wounded on CS, German wounded on CS, sometimes side by side. When Patterson reached Ernst, he paused. Jesus Christ, he said, examining the feet.

Then to a nurse, get me a basin of warm water, not hot, warm, and morphine. This is going to hurt like hell. In Germany, Erns said carefully. They would cut both feet already gone. Patterson looked at him. Really looked not at the enemy, at the person. Yeah, I know. German protocol. Amputate everything that is black,” he paused. “But I do not think everything that is black is dead, and I am not cutting until I am sure.

” As Patterson lowers Ern’s foot into the water again, Ern’s mind flashes to the barracks poster. The ape-like American face. See Kennan Kaggnod. Patterson’s hands are gentle, careful, steady. The sergeant’s voice echoes in memory. They will torture you for information. Easy now, Patterson says. I know it hurts.

That means it is alive. The contradiction makes Ern’s head swim worse than the morphine. Other doctors stop by, shake their heads. You are wasting time, Jim. Those feet are gone. Just take them off and move to the next guy. Not yet, Patterson replies. Not defensive, just certain. Between treatments, Patterson talks to him.

Not interrogation, conversation. You in school before the war? Medicine, Ernst answers. Second year, Patterson’s eyebrows rise. No What specialty? Surgery. Like my father. Well, Patterson says, examining a toe with those steady surgeons hands. You are going to need feet if you want to stand in an operating room for hours.

So, let us see if we can save these. Something cracks in Ernst’s understanding of the world. This American knows Ernst was training to be a surgeon. knows Ernst’s future depends on these feet. And instead of seeing poetic justice in their destruction, Patterson is fighting to preserve that future. “What year are you?” Ernst asks, surprising himself.

The morphine is making him bold. “Finished my residency in 1939, 5 years out. Patterson manipulates Ernst’s ankle, checking range of motion. Was supposed to take over my father’s practice in Chicago. Heart surgery. Then Pearl Harbor happened. You could have stayed. Doctors are exempt. Deferred, not exempt. Could have claimed it.

Patterson shrugs. Did not feel right. My brother enlisted the day after Pearl Harbor. Died at Guadal Canal in 1942. His hands do not stop moving. Professional, steady. Figured if Tommy could go, so could I. Ernst is quiet. He had assumed American doctors joined for glory or patriotism, not grief, not obligation to dead brothers.

I am sorry, Ernst says. Patterson looks up surprised. For what? Your brother. For a long moment, Patterson just studies him. Then, yeah, me too. He returns to the feet. War is full of brothers who do not come home on both sides. The acknowledgement hangs between them. Your grief matters too, even though you are the enemy.

Why? Ernst watches Patterson’s hands move with practice precision, checking circulation, mapping the boundary between living and dead tissue, testing nerve response with careful pressure. These are surgeons hands. His father had hands like these. A nurse brings coffee. Patterson waves it away without looking up. Doc, you have been at this for 4 hours.

I know how long I have been at it. Margaret Ernst realizes something. Patterson is not doing this out of obligation. He is invested now. Personally invested in saving these feet. It is no longer about protocol or duty. It is about refusing to accept defeat. Why do you do this? Ernst asks finally. The Geneva Convention says you must treat, but not like this. Not 5 hours for enemy feet.

Patterson is quiet, hands still working. Then my dad is a surgeon too in Chicago. When I told him I was joining up, he said, “You are going to see horrible things, but you are still a doctor first.” And doctors serve life, not flags. Doctors serve life, not flags. Ernst thinks of his father’s letter. We serve life, not death.

Two surgeons, two countries, same conviction. The propaganda never mentioned this possibility, that the enemy might share your values, that an American doctor might fight for a German soldier’s future with the same intensity a German doctor would. The color begins to change. Not everywhere, but in places. Black giving way to purple, then red.

Circulation returning in stuttering bursts. Patterson documents every change, mapping survival. Ernst can move three toes on his right foot. Patterson sits back with quiet satisfaction. We are not out of the woods. You will lose some tissue, definitely some toes, but I do not think we need to take everything.

He meets Ernst’s eyes. We can save enough that you will walk again, maybe even stand in an operating room. Ernst cannot speak. The morphine is wearing off, pain radiating up his legs. But that is not why he is silent. He is silent because every certainty he carried into that foxhole has just been destroyed by six hours of American compassion.

Two weeks later, the recovery ward held 10 CS in a tent designed for six. Ernst found himself between Tommy, a paratrooper from Minnesota with shrapnel in his shoulder, and deer, a panzer grenadier from Stutgart with a shattered collarbone. “You the frostbite guy?” Tommy asked the first day as casually as dormatory roommates.

Heard Patterson worked on you for 6 hours. Doc is stubborn as hell. Deer was less conversational. He watched the Americans with wary suspicion. When a nurse came to change his bandages, he flinched. They are going to kill us. Deer whispered to Ernstston in German. When we are no longer useful, you will see.

But days passed and no one was killed. Instead, they were fed real food. Not abundant, but regular. Same rations for American and German wounded. Same portions, same quality. Ernst watched the contradictions multiply. A medic teaching a young German private how to properly clean a wound so it would not get infected. An American lieutenant sharing his blanket with a shivering Luftwafa pilot.

The chaplain, an earnest man from Ohio, offering to pray with Germans in their own language, stumbling through unfamiliar words with genuine effort. One morning, Ernst woke to find Tommy and Deer playing cards. Not just playing laughing. Tommy was attempting German phrases, getting them magnificently wrong, and Deer was correcting him between hands of poker.

“Your accent is terrible,” Deer said in broken English. Yeah, well, your poker face is worse,” Tommy shot back. They grinned at each other. Enemy soldiers sharing cigarettes and terrible jokes. Ernst watched Deer’s conviction slowly erode against the mundane reality of equal treatment.

It was not dramatic, no speeches, no grand gestures, just the quiet accumulation of evidence that the propaganda had been wrong. Patterson visited daily. The progress was microscopic but measurable. Some toes would survive, others would not. But the line between amputation and recovery kept shifting in Ern’s favor. You are lucky, Patterson said during one examination.

Another 6 hours in that foxhole, and there would not have been anything to save. Lucky, Ernst repeated. Captured by the enemy, feet partially destroyed, country losing the war. But yes, somehow lucky. Why did you believe it? Patterson asked one day. Believe what? The propaganda about Americans. You seem smart.

How did they convince you we were monsters? Ernst considered the question. In the tent, Tommy was teaching a young German prisoner poker. A nurse was helping deer write a letter to his mother. They told us specific stories, Erns said. Showed us pictures of bombed cities. Our cities. said, “You did it because you hated us.” He paused.

“I was afraid, and fear makes you believe things. Easier to be terrified of monsters than to face human enemies who might be right about the war.” Patterson nodded slowly. “We got told stories, too. Some of them were true.” He looked at Erns directly. “Some of what you heard about us was probably true, too.

War makes monsters of everyone sometimes. question is whether we let it make monsters of us all the time. That conversation stayed with Ernst because Patterson was right. Some of the stories had been true. Ernst had heard the rumors about the camps, the occupied territories, had chosen not to think too carefully.

If Germans could commit atrocities while claiming civilization, could not Americans be humane while prosecuting war? The transformation happened in small moments. The nurse who learned German words just to ask if Ernst was comfortable. The chaplain who offered to mail a letter to Ernst’s father. No censorship.

Tommy sharing cigarettes with Deer who had been part of the force that wounded him. When another German prisoner insisted the Americans were only treating them well because of Red Cross inspectors. Deer cut him off. Then why work 6 hours on his feet? Deer pointed at Ernst. Why fight for tissue everyone said was dead? No one was watching that except us.

The prisoner had no answer. Ernst did. He did it because he is a doctor and doctors serve life, not flags. His father’s words. Patterson’s words. The words that bridged two countries and one shared profession. 3 weeks after capture, Patterson told Ernst he was being transferred to a larger P facility. Your feet need less intensive care now.

You will finish recovery there. He paused. Probably lose three toes on your right foot, two on your left, but you will walk, maybe even run with time. Thank you, Ern said. The words felt inadequate for 6 hours when everyone said to amputate, for seeing a person instead of an enemy, for saving his future. Patterson just nodded.

When you get back to Germany after the war, finish your medical training. Be a good surgeon. He paused. and maybe remember that your enemy once fought to save your feet and ask yourself what that means about how we divide the world into us and them. On the truck to the P camp, another prisoner started repeating the old propaganda, “Americans are barbarians.

We will be shot eventually. This is all a trick.” Deer cut him off. Shut up. Just shut up. Smiled. One more transformation. One more certainty. Destroyed. Spring 1945. Ernst Bower lost four toes total. Three on the right foot, one on the left. He kept his balance, his ability to stand, his future.

The P camp in France bore no resemblance to the sergeant’s descriptions. No torture, no executions, adequate food, medical care, mail service. The Geneva Convention actually observed he spent six months there working in the camp infirmary alongside American medics. They taught him techniques he had never seen in German medical school.

Taught him willingly as if sharing knowledge with the enemy was the most natural thing in the world. One medic, a man named Roberts from Tennessee, showed Ernst a new suturing technique for minimizing scars. “You are going back to surgery after this?” Roberts asked. If I can, Erns replied, looking at his damaged feet. You can, Patterson made sure of that.

Roberts tied off a stitch with practiced efficiency. He told me about your case. Said you had the hands of a surgeon. Said it would be a waste if you did not use them. Ernst had been an enemy, an invader, part of the force that had killed American soldiers. And Patterson had told his colleagues that Ernst hands were too valuable to waste.

He returned to Hamburg in late 1945. His family home was rubble. His father had died in the final weeks, killed by artillery while treating wounded. His mother looked decades older. “Your feet,” she said, looking down. “You are walking.” “An American doctor saved them,” Ernst replied. She was quiet for a long moment.

“Then your father would have approved.” 1946 Ernst returned to medical school in a university operating out of damaged buildings with salvaged equipment. His class was veterans and displaced persons trying to build something from ruins. On his first day of surgical rotation, the professor asked why they had chosen surgery.

When Ern’s turn came, he looked at his scarred feet, functional, weightbearing, the feet that let him stand in this operating room and said, “Because a doctor once spent 6 hours fighting for tissue everyone said was dead.” He taught me that being a surgeon means serving life even when it seems irrational. The professor, an older man who had survived the war by staying quiet and keeping his head down, gave Ernst a long look.

Irrational medicine wastess resources. Respectfully, hair professor, I disagree. Ernst held his ground. That doctor saved tissue that every German protocol said to amputate. Because of his irrational persistence, I am standing here. I will perform surgeries for decades. I will save other patients. That is not waste. That is investment.

The professor’s expression softened slightly. And this doctor, he was German, American. He was the enemy. I was his prisoner. The classroom went silent. Then perhaps, the professor said quietly. We have more to learn from our enemies than we thought. Continue, Hairbower. It was the first time Ernst had spoken publicly about Patterson.

It would not be the last. 40 years of surgery followed. Ernst specialized in reconstructive procedures. the painstaking work of saving damaged tissue, restoring function, fighting for inches of recovery. Other surgeons wrote off as hopeless. His colleagues called him stubborn. His patients called him thorough.

Ernst thought of it as carrying forward a lesson learned in an American field hospital. He never forgot the lesson source. In 1961, Ernst wrote his first letter to James Patterson. It took 6 months to reach him in Chicago where Patterson was chief of surgery. Patterson wrote back, “Ernst, I remember your case. Glad the feat held up.

Even more glad you became a surgeon. The world needs doctors who understand their job is preserving life, not serving ideology. If you are ever in Chicago, look me up.” They corresponded for 32 years. letters about surgical techniques and medical advances about families Patterson’s three children Erns too about the long shadow of war and the longer work of building peace 1977 Erns testified at a medical conference in Frankfurt about treatment protocols for severe frostbite he presented Patterson’s technique rapid rewarming

with extended care as a case study in challenging medical dogma the standard German protocol in 194 1944 was immediate amputation of black tissue. Erns told the assembled doctors it was efficient, logical, it saved many lives, but it was incomplete. He showed photographs of his feet, the scarring, the missing toes, the undeniable evidence that he was standing before them.

I have performed over 10,000 surgeries in my career, most of them standing for 6, 8, sometimes 12 hours at a time. None of that would have been possible if an American doctor had accepted the standard protocol in December 1944. The room was silent. The lesson is not just about frostbite treatment. It is about what happens when we see patients as individuals instead of statistics.

When we fight for outcomes everyone else has written off when we choose to serve life over expedience. The protocol he presented Patterson’s protocol refined by those steady hands in a tent outside Bone became standard treatment in German medical schools. 1993 Ernst retired from surgery. His hands were not as steady anymore.

His feet, those improbable survivors, achd after long days in the operating room. At his retirement dinner, colleagues asked about his most memorable case. Erns told them about a 23-year-old soldier pulled from a foxhole with blackened feet and no hope. About an American captain who chose to fight when every protocol said to amputate.

About 6 hours that changed one life and echoed through 40 years of surgical practice. He saved my feet, Erns said, that let me stand in operating rooms for 40 years saving others. Every patient I treated, every procedure I performed, every life I helped preserve, all of it, traces back to Captain Patterson’s decision to see possibility instead of loss.

He paused, looking at the assembled doctors, some of whom he had trained. The war tried to teach us that enemies are less than human, that American doctors would torture German prisoners. Captain Patterson proved every word of it was a lie. And in doing so, he did not just save my feet, he saved my understanding of what it means to be a doctor.

2003, Erns Bower died at age 81. His obituary noted his 40-year career in reconstructive surgery and his contributions to Frostbite treatment protocols. It did not mention that he had been an enemy soldier once, that an American doctor had given him a future he had no right to expect. But at his funeral, among the flowers and condolences, there was a telegram from Chicago from James Patterson’s daughter, Patterson himself, had died in 1998.

It said simply, “Dad always remembered the German medical student whose feet he saved.” He said, “You proved he had made the right choice. Rest well, Dr. Bower. You honored his legacy.” Two surgeons, two countries, one shared conviction that life deserves to be fought for. even especially when the odds say otherwise.