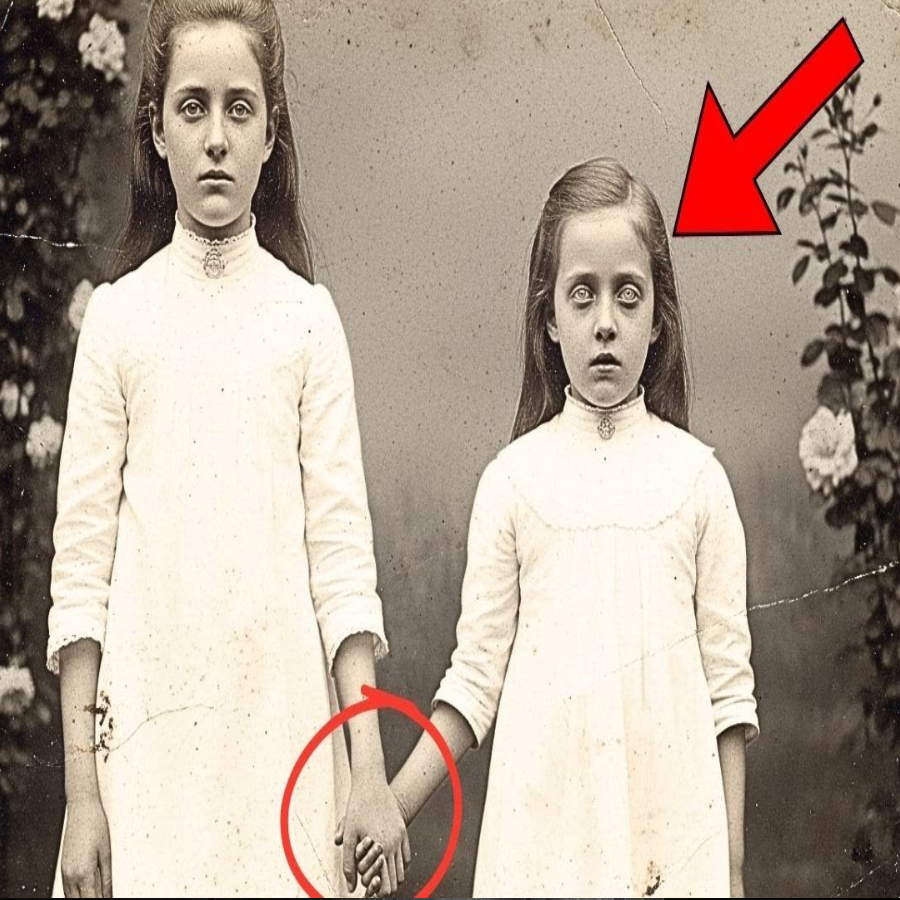

When museum curator Dr. Helen Foster examined this 1895 photograph in 2021, she saw what everyone else had seen for 126 years. Two sisters in matching white dresses holding hands in a garden, their faces serious in that typical Victorian way.

The photograph had been donated anonymously to the Boston Historical Society with only a handwritten note. The Davy’s sisters, 1895. May they finally rest. Helen almost filed it away without a second thought. But then she noticed something odd about the smaller girl’s hand. The way the fingers curled, the unnatural angle. She ordered a highresolution scan. What the restoration revealed made Helen understand why this photograph had been hidden for over a century and why the note said, “Finally, rest.

This isn’t just a photograph of two sisters. It’s a photograph of a promise that lasted beyond death. The photograph arrived at the Boston Historical Society on March 15th, 2021 in a plain manila envelope with no return address.

Inside was a single sepia toned photograph approximately 5×7 in mounted on thick cardboard backing typical of 1890s studio photography. The image showed two girls standing in what appeared to be a garden. The older girl, perhaps 10 or 11 years old, stood on the left wearing a white Victorian dress with lace collar and puffed sleeves.

Her dark hair was pulled back severely from her face. Her expression was solemn, almost haunted. Beside her stood a smaller girl, maybe six or seven, also in white. She was shorter, thinner, with the same dark hair and serious expression. The younger girl’s right hand was held by the older girl’s left hand. Their fingers were intertwined tightly.

Behind them was a backdrop of climbing roses on a trellis. Soft afternoon light suggested the photograph had been taken outdoors, which was unusual for the era when most portraits were done in studios with controlled lighting. At the bottom of the photograph, written in faded brown ink, were the words, “Liy and Rose Davies, June 1895.

” The accompanying note written on modern paper in shaky elderly handwriting, said only, “The Davy’s sisters, 1,895. May they finally rest. I can’t keep this any longer. Someone should know the truth. Dr. Helen Foster, age 52, had been curator of the photographic archives at the Boston Historical Society for 18 years. She had seen thousands of Victorian photographs.

This one seemed unremarkable at first glance, just another formal portrait of children from a wealthy family, the kind of image that filled countless archives across the country. But something bothered Helen. She couldn’t quite identify what it was. She examined the photograph more closely with a magnifying glass.

The older girl, Lily, according to the inscription, had her eyes focused directly on the camera. Her expression was difficult to read, not quite sad, not quite angry, something closer to resignation or perhaps determination. The younger girl, Rose, had her head tilted slightly toward her sister. Her eyes were also on the camera, but they seemed unfocused, glazed.

Her mouth was slightly open, and then Helen noticed the hand. Rose’s hand, the one holding Lily’s, had an odd quality to it. The fingers were curled in a way that didn’t seem natural. The skin tone appeared slightly different from the rest of her visible skin. darker perhaps or discolored in a way that the sepia tone didn’t quite hide.

Helen pulled out her measurement tools and examined the photographs dimensions and mounting style. Everything was consistent with 1895 photography techniques. The image wasn’t a modern forgery, but there was something wrong about it that she couldn’t articulate. She decided to have the photograph digitally scanned at the highest possible resolution.

The society had recently acquired a new scanner capable of capturing detail at 12,800 dpi, resolution that would reveal things invisible to the naked eye, things that Victorian photographers and viewers would never have seen. The scan was scheduled for March 18th, 3 days later. Helen placed the photograph in an archival storage box and tried to put it out of her mind. But that night, she dreamed about it.

In the dream, the two girls in the photograph were standing in her office. The older girl, Lily, was crying silently. The younger girl, Rose, stood perfectly still, not blinking, not breathing. And Lily kept whispering the same words over and over. I promised. I promised I’d never let go. I promised.

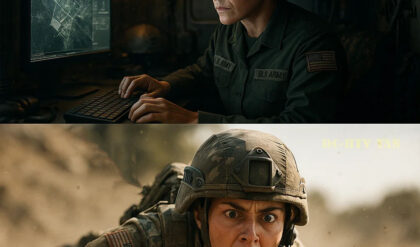

The highresolution scan took 4 hours to complete. Helen stood in the society’s digital laboratory with Marcus Chen, their imaging specialist, watching as the photograph was slowly processed by the scanner’s array of sensors. The machine captured not just the visible image, but also infrared and ultraviolet signatures that could reveal hidden details, alterations, or damage invisible to normal viewing.

When the scan was complete, Marcus loaded the file onto his workstation. The image appeared on the large 4K monitor in stunning detail. Every grain of the photographic emulsion was visible. every tiny scratch and imperfection in the mounting board, every fiber of the paper.

“Let’s start with a general examination,” Marcus said, zooming in to 200%. “The photograph is authentic, definitely from the 1890s based on the paper composition and emulsion type. No signs of modern manipulation or forgery.” Helen leaned closer to the screen. Can you focus on the younger girl on her hand? Marcus zoomed in on Rose’s right hand, the one holding Lily’s.

At 800% magnification, details emerged that had been impossible to see with the naked eye. The skin texture was wrong. While Lily’s hand showed the normal fine lines and texture of living skin, Rose’s hand had a waxy, almost artificial quality. The fingers, which had appeared merely oddly positioned at normal viewing, were now clearly visible as rigid, held in place not by muscle, but by something else. That’s liver mortise, Helen whispered.

Post-mortem lividity, the darker discoloration. That child was dead when this photograph was taken. Post-mortem photography was common in the Victorian era, but those photographs were always obviously post-mortem. Children posed in coffins or beds, clearly deceased, often with flowers, meant as memorial portraits.

This photograph was different. This photograph was meant to look like both girls were alive. Marcus pulled up the infrared layer of the scan. In infrared, living tissue and dead tissue reflected light differently. The difference between Lily and Rose became stark and undeniable. Lily’s body showed the heat signature patterns consistent with a living subject, or rather the residual patterns that living subjects left in photographs even after 126 years.

Rose’s body showed nothing. No heat signature at all, just cold uniform reflection. The older girl was alive, Marcus confirmed. The younger one had been dead for some time. Based on the skin discoloration visible in this resolution, I’d estimate at least several days, maybe a week. Helen felt a chill run down her spine.

Show me their faces. Maximum detail. Marcus zoomed in on Rose’s face at 1,600% magnification. The details were devastating. The child’s eyes, which had appeared merely unfocused at normal viewing, were now clearly visible as clouded. The corneas had begun to develop the milky opacity that occurs hours after death.

Her slightly open mouth revealed the tip of her tongue, which had a darkened, desiccated appearance. But most heartbreaking was the makeup. At this magnification, Helen could see that someone had carefully applied powder and rouge to Rose’s face to give her cheeks artificial color. Someone had positioned her carefully to hide the worst signs of death.

Someone had gone to extraordinary lengths to make her look alive. Now Marcus zoomed in on Lily’s face. tears barely visible at normal resolution but unmistakable at this magnification. Lily had been crying when the photograph was taken. Her eyes were red rimmed. Tear tracks were visible on her cheeks beneath the powder she too was wearing. And there was something else. Something written on the mounting board beneath the photograph.

So faint it was invisible without digital enhancement. Marcus adjusted the contrast and sharpening. Words appeared written in pencil in a child’s handwriting. I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever. I kept my promise. June 12th, 1895. Helen immediately began searching historical records for the Davies family.

Finding information from 1895 was challenging, but the Boston Historical Society had extensive archives and connections to genealogical databases. Within 2 days, Helen had found them. The Davies family had lived in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. The father, Robert Davies, was a successful textile merchant. The mother, Eleanor Davies, came from old Boston money.

They had two daughters, Lily, born March 1884, and Rose, born September 1888. Rose Davies died on June 3rd, 1895 at age 6 years and 9 months. Cause of death, scarlet fever. Lily Davies died 7 days later on June 10th, 1895 at age 11 years and 3 months. cause of death, also scarlet fever.

The photograph was dated June 1895, which meant it had been taken sometime between Rose’s death on June 3rd and Lily’s death on June 10th. Helen found the death certificates in the Massachusetts State Archives. Both girls were buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery on June 11th, 1895 in the family plot. A joint funeral service was held at Trinity Church, but there was something odd about the burial records.

The notation for Rose’s burial said, “Delayed interment due to family circumstances. Body held at family residence June 3rd to 10th.” Rose’s body had been kept at home for 7 days before burial. In June in Boston, where temperatures that week, according to weather records, had reached the mid80s, Helen found a newspaper article from the Boston Globe, dated June 12th, 1895.

Tragedy strikes Davy’s family, both daughters lost to scarlet fever. The prominent Beacon Hill family of Robert and Elellanar Davies mourns the devastating loss of both their daughters within the span of one week. Rose Davies, age 6, succumbed to scarlet fever on June 3rd.

Her sister Lily, age 11, fell ill shortly after and passed away on June 10th. Sources close to the family report that Lily refused to leave her sister’s side during her illness and insisted on remaining with her even after Rose’s passing. The double funeral was held yesterday at Trinity Church. Mrs. Davies is said to be prostrate with grief and under doctor’s care.

Helen cross referenced this with city records and found something else. On June 8th, 1895, a physician named Dr. Samuel Morrison had been summoned to the Davies household by neighbors who reported concerning circumstances. Dr. Morrison’s report filed with the city health department stated responded to 44 Beacon Street regarding welfare concerns.

Found surviving child Lily Davies age 11 refusing to be separated from deceased sister’s body. Child stated she had promised mama to stay with her sister. Mother and father are both ill with grief and fever. Father recovering from scarlet fever himself. Mother in state of nervous collapse. Child has been sleeping beside deceased sister’s body for 5 days.

Despite health concerns, family refused to allow immediate burial. Recommended urgent intervention, but no intervention had occurred. Rose’s body remained at the house for two more days. And at some point during that week, someone had arranged for a photographer to come to the house. Someone had posed the two girls together in the garden, had dressed them in matching white dresses, had positioned them holding hands, had told Lily to look at the camera and try not to cry.

Someone had created a photograph that showed both Davey’s daughters together one final time, as if both were still alive. Helen’s research led her to the archives of the Boston Photographers Guild where she found records of active photographers in 1895. One name appeared in connection with the Davies family.

Thomas Blackwell, a photographer who specialized in memorial portraits. His business ledger preserved in the society’s collection contained an entry dated June 7th, 1895. Davy’s Residence, 44 Beacon Street. Memorial portrait. Two subjects. Special arrangements. Payment $50. $50 in 1895 was an extraordinary sum, roughly $1,800 in modern currency, far more than a typical memorial photograph would cost.

Helen searched for more information about Thomas Blackwell and found his personal diary which had been donated to the society in 1957 by his granddaughter. She requested the diary from storage and when it arrived she carefully turned the fragile pages to June 1895. The entry for June 7th 1895 was longer than most.

received urgent summons to the Davy’s household on Beacon Hill. The situation there is among the most disturbing I have encountered in 20 years of memorial photography. The younger daughter, Rose, died of scarlet fever 4 days ago. The older daughter, Lily, has also contracted the disease and will not survive long, according to the family physician. But the true horror is this.

Lily has refused to leave her deceased sister’s side. She sleeps beside the body. She holds the dead child’s hand. She speaks to her as if she were alive. The mother is too overcome with grief to intervene. The father is weak from his own illness. They sent for me because Lily requested it.

The child wants a photograph of herself with her sister so mama can remember us together. I tried to explain that we could create a traditional memorial portrait, but Lily became hysterical. She demanded the photograph show both of them alive and together. She made me promise to pose them in a way that would hide the fact that Rose was deceased.

I am deeply uncomfortable with this deception, but the child is dying and her parents are too broken to refuse her anything. I agreed. God forgive me. I agreed. I photographed the two girls in the garden, positioned carefully so that Rose’s condition would not be obvious. I posed them holding hands as Lily insisted.

The older girl never stopped crying, but she tried to hold still for the exposure. She whispered to her sister throughout, telling her to stay calm, stay still just a little longer. The younger girl, of course, remained perfectly still. I completed the work in half an hour and left as quickly as possible. The father paid me double my usual rate and begged me never to speak of this.

I will honor that request. But I will never forget the sight of that living child clutching her dead sister’s hand, trying so desperately to pretend everything was normal, trying so desperately to keep a promise she should never have been asked to make. Helen sat back, her hands trembling. The photograph suddenly made terrible sense.

This wasn’t a deception meant to fool others. It was a gift from a dying girl to her griefstricken parents. A lie told out of love. A final attempt to give them one memory that wasn’t drenched in tragedy. Lily had known she was dying. She had known this photograph would be the last thing she ever did. And she had used it to create an illusion, a moment frozen in time where both Davey’s daughters were together, alive and whole.

Lily Davies died 3 days after the photograph was taken. Helen found her death certificate and medical records. The attending physician, Dr. Samuel Morrison, noted. Patient declined rapidly following prolonged exposure to deceased sibling. Scarlet fever complicated by exhaustion and grief. Patient refused all food and water in final 48 hours. Last words. I kept my promise.

Lily was buried beside Rose on June 11th, 1895. The joint funeral was attended by over 200 people. The Boston Globe reported that Elellanar Davies, the girl’s mother, collapsed during the service and had to be carried from the church. Helen searched for what happened to the parents after their daughter’s deaths.

The records were heartbreaking. Eleanor Davies never recovered. She was admitted to Mlan asylum in August 1895, diagnosed with acute melancholia and nervous prostration. She spent the remaining 12 years of her life there, mostly unresponsive, staring at a photograph she kept in her room.

According to asylum records, it was a portrait of her two daughters in white dresses holding hands. The photograph Helen was now examining. Robert Davies sold the Beacon Street house in September 1895. He moved to New York and tried to rebuild his life. He remarried in 1899, but the marriage was short-lived. His second wife left him, citing his obsession with the dead.

Robert died in 1904, age 49, of heart failure. His obituary mentioned his first family only briefly, preceded in death by his daughters, Lily and Rose, and his first wife, Ellaner. But the photograph’s journey didn’t end there. Helen traced its ownership through the decades.

After Elellanar’s death in 1907, her few possessions were sent to her sister Margaret Hartwell, who had been estranged from Eleanor during her lifetime. Margaret took one look at the photograph and understood immediately what it showed. She wrote in her diary. Ellaner kept this photograph in her room at the asylum for 12 years. She would stare at it for hours, whispering to her girls. I understand why now.

Lily is alive in this image, but Rose is already gone. Eleanor was looking at the moment between the moment when she still had one daughter left, trying to pretend she had both. It’s the crulest kind of comfort. I cannot keep it. It’s too painful, but I cannot destroy it either. It’s all that remains of those poor children.

Margaret stored the photograph in a trunk where it remained for 50 years until her death in 1957. Her daughter Catherine inherited it and kept it hidden, never showing it to anyone. Catherine died in 1998, and the photograph passed to her son, James Hartwell, age 73. James was the one who finally sent it to the historical society in 2021.

Helen managed to track him down through genealogical records and called him. I’m 94 years old. James told her, his voice weak, but clear. My mother told me about that photograph when I was young. She said it was cursed, not by magic, but by love. She said it showed what love looks like when it refuses to let go. Even when letting go is the only mercy left.

I’ve carried that photograph for 23 years since my mother’s death. I’m dying now. Cancer. I don’t want my children to inherit this burden. Let history have it. Let someone else remember those girls. He died two weeks after sending the photograph. His obituary made no mention of the Davy’s sisters or the photograph.

Dr. Helen Foster presented her findings to the Boston Historical Society’s board in April 2021. The response was divided. Some members felt the photograph should be displayed as an important historical artifact illustrating Victorian attitudes toward death and childhood.

Others argued it was too disturbing, too private, too painful to share publicly. Helen advocated for a middle path. Preserve it, document it, but restrict access. Make it available to researchers, but not as a casual exhibit. Respect the tragic history it represented. The board agreed. The photograph was cataloged, digitally preserved, and placed in the society’s restricted archives.

A detailed historical file was created documenting everything Helen had discovered about the Davies family. But Helen couldn’t stop thinking about one detail, the hidden inscription. I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever. What promise had Lily made? And when Helen returned to the medical records and found something she’d missed initially, Rose Davies had been sick for 3 weeks before she died.

During that time, according to Dr. Morrison’s notes, Lily had refused to leave her sister’s bedside. In a note dated May 28th, 1895, 6 days before Rose’s death, Dr. Morrison wrote, “Elder sister Lily has contracted scarlet fever, but insists on remaining with younger sister Rose despite risk of worsening her own condition.

When I attempted to separate them, Lily became hysterical. She claims she promised Mama she would hold Rose’s hand until everything is better. Mrs. Davies, in her distress, has supported this arrangement. I fear both children will be lost. The promise hadn’t been about death. It had been about comfort.

Elellanar Davies, watching her younger daughter suffer from scarlet fever, had asked Lily to hold Rose’s hand, to comfort her, to stay with her until everything is better. Lily had interpreted that promise literally. She held Rose’s hand while she was sick. She held it when Rose died. She held it for 7 days afterward, and she demanded a photograph showing her keeping that promise, even though better would never come. Helen discovered one final document that made her weep.

A letter written by Elellanar Davies while in Mlan asylum, dated 1901, found in the asylum’s archives. My dear Lily, I should never have asked you to make that promise. You were a child. You took my careless words and turned them into an obligation that cost you your life. You stayed with Rose when you should have fled. You breathed the same air as your dying sister.

You exhausted yourself caring for her. And when she died, you couldn’t let go because you’d promised me. You died because of a promise you should never have had to keep. I live in hell every day knowing that I killed both my children. Rose with disease and you with love.

The photograph torments me because it shows the exact moment of your sacrifice. You standing there already dying, pretending for my sake that everything was normal. Pretending for my sake that Rose was still alive. creating one last beautiful lie because you loved me too much to let me remember only pain. I’m sorry, my darling girl. I’m so so sorry. Please forgive me. Please rest.

The letter was never sent. It was found in Elellanar’s room after her death, addressed but unsealed. The photograph remains in the archives, a testament to a promise kept at too high a cost. A memorial not to death, but to the terrible weight of love. When Helen looks at it now, she doesn’t see deception.

She sees a child trying to protect her mother from unbearable truth. She sees devotion that transcended life and death. She sees what love looks like when it refuses to surrender. Even to the inevitable, even to mercy, even to peace. The photograph remains sealed in the archives. Some loves are too painful to display. Subscribe for more hidden stories behind history’s most heartbreaking