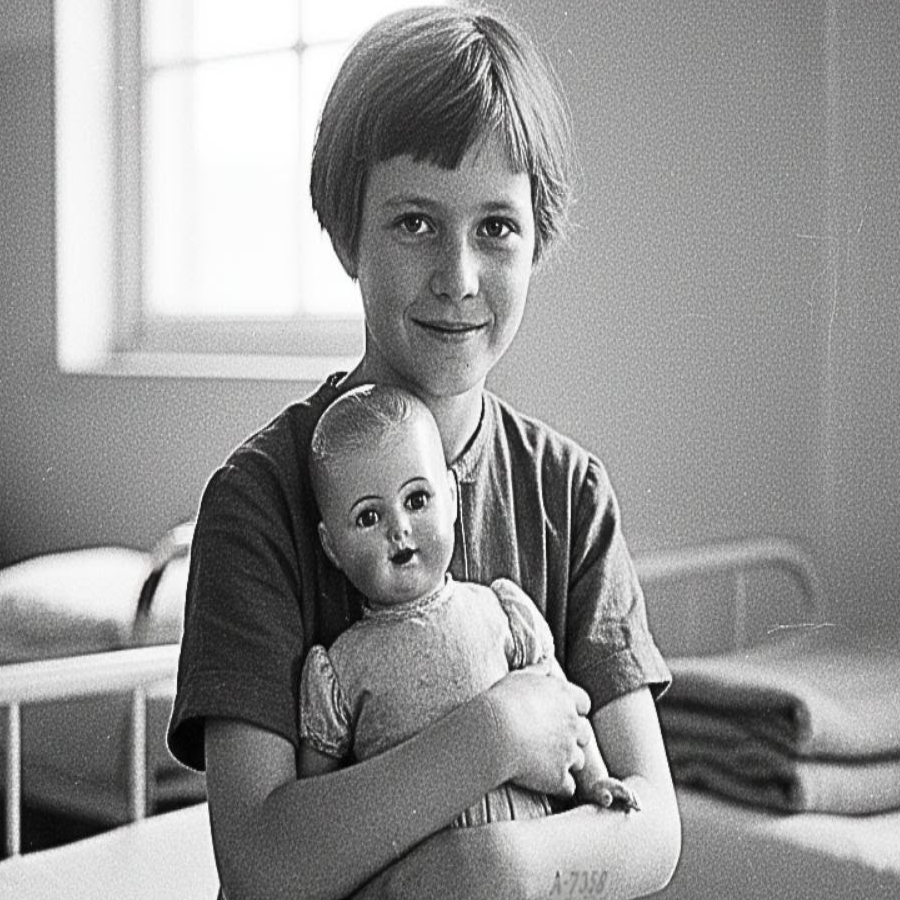

In August 2024, while digitizing photographs from liberated concentration camps for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, researcher Dr. Sarah Lieberman examined a 1945 image from Bergen Bellson. The photograph showed a small girl, approximately 6 years old, sitting on a cot in the children’s recovery ward, holding a donated doll and offering a tentative smile to the camera.

one of thousands of liberation photos documenting survivors. The image had been filed as unidentified child survivor, May 1945. But when Dr. Lieberman examined the photograph at high resolution and zoomed in on the child’s left hand, she noticed something that had been missed for 79 years.

A number tattooed on her tiny forearm. a detail that would lead to identifying this child and uncovering her remarkable story of survival. Dr. Sarah Lieberman had worked at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC for 12 years, specializing in photographic archives and survivor identification. Her department received approximately 500 new photographs annually from various sources, donated by families, discovered in archives, acquired from estate sales, or digitized from military records.

In August 2024, the museum received a collection of 847 photographs from the estate of Captain James Walsh, a US Army medical officer who served with the units that liberated Bergen Bellson concentration camp in April 1945. Captain Walsh had died in 2023 at age 102, and his family donated his personal papers and photographs to the museum.

Sarah was assigned to catalog and digitize the collection. Among the photographs were images documenting the immediate aftermath of liberation, survivors in hospital wards, medical personnel treating patients, distributions of food and clothing, and children in recovery facilities. One photograph labeled in Captain Walsh’s handwriting as little girl with doll children’s ward May 12th, 1945 showed a small child sitting on a metal frame caught.

She wore an oversized donated dress. Her hair had been recently cut short, likely shaved due to lice and disease, now growing back unevenly. She held a porcelain doll almost as large as herself. Her expression was uncertain, not quite smiling, but attempting to smile for the camera. Sarah had seen thousands of similar photographs. Each one was heartbreaking.

Each documented the immediate aftermath of liberation when survivors, many of them children, were beginning the long process of physical and psychological recovery. Sarah scanned the photograph at 6,400 dpi, the museum’s standard for archival digitization. She examined the highresolution image on her computer, noting details for the catalog entry.

Then she zoomed in on the child’s hands. The left hand was partially wrapped around the doll’s body. At 400% magnification, Sarah could see something on the child’s tiny forearm just above the wrist. Numbers. Tattooed numbers. Sarah’s breath caught. She zoomed in further. The tattoo read a 7358. Sarah immediately understood the significance.

Ashvitz had tattooed prisoners with identification numbers. The A series was used in 1944 for a specific group of prisoners, but Avitz tattoos on children were relatively rare. Most children sent to Avitz were murdered immediately upon arrival in the gas chambers. Those who were tattooed had been selected for forced labor or medical experiments, or were kept alive for other reasons.

A child this young, perhaps 6 years old, with an Awitz tattoo had survived something almost unimaginable. Sarah pulled up the museum’s database of registered Avitz numbers. The A series numbered approximately 20,000 prisoners registered from May to July 1944. She searched for A7358. The database showed A7358 female registered May 28th, 1944.

Dash dash Noame recorded dash dash. No additional information. Ashvitz records were incomplete. Dash Many had been destroyed by the Nazis before liberation. Thousands of prisoners were registered with numbers but no names. For many survivors, the only proof of their imprisonment was the number tattooed on their arm.

But Sarah now had something rare, a photograph of a child with a visible tattoo number taken shortly after liberation at Bergen Bellson. If this child had survived, if she had been reunited with family or placed with survivors organizations, there might be records, there might be a name, there might be a story.

Sarah began the search to identify A7358. Dr. Lieberman initiated a comprehensive investigation to identify the child in the photograph. She began with what she knew. Known facts. Awitz. Prisoner number A7358 registered May 28th, 1944. Gender, female, approximate age in photo, 6 years old, suggesting birth year, 1938 to 1939. Location when photographed, Bergen Bellson, British controlled zone, May 12th, 1945.

Physical appearance, light brown hair, thin build, small stature. The historical context. Sarah researched the A series registrations at Avitz. This series was used for a specific group. Hungarian Jews transported to Avitz in spring summer 1944. In May to July 1944, approximately 440,000 Hungarian Jews, Jews were deported to Ashvitz in one of the most intensive periods of the Holocaust.

Most were murdered immediately. Those selected for forced labor were tattooed and registered. Children were almost never selected for labor. They were sent directly to the gas chambers. But there were exceptions. Twins selected by Dr. Joseph Mangala for medical experiments. Older children 12 to 16 who lied about their age and were selected for labor.

Occasionally young children kept alive for specific reasons. Children with parents or relatives who were able to protect them. A six-year-old with a tattoo meant she had somehow survived selection, survived Achvitz, and eventually been transferred to Bergen Bellson before liberation. Searching the records, Sarah contacted several organizations.

One, Arlson Archives, Germany, International Center on Nazi Persecution. They had incomplete records showing A7358 was registered at Ashvitz on May 28th, 1944. But no name, no transport list connection, no liberation records. Two, Yad Vashm, Israel World Holocaust Remembrance Center. Their database showed a transport from Monkach, Hungary to Ashvitz, arriving May 28th, 1944.

That transport included approximately 3,000 people. Records showed 2,847 were murdered immediately. 153 were registered and tattooed. Among those were approximately 12 children under age 10, an unusually high number for selection. Three Bergen Bellson Memorial Archives. They had liberation records showing approximately 500 children under age 12 were found at Bergen Bellson when British forces liberated the camp on April 15th, 1945.

Most were in critical condition. Many died in the weeks following liberation despite medical care. British military records documented attempts to identify survivors, but many children had no identification. didn’t know their names or were too young or traumatized to provide information.

Four Jewish family search organizations Sarah contacted organizations that helped survivors locate family members after the war. She searched records of children placed in displaced persons camps, orphanages, and with foster families. The breakthrough. After three weeks of searching, Sarah found a document in the Bergen Bellson archives, a handwritten list titled Children’s Ward, unidentified, May 1945.

Entry number 47. Female child approximately age 6. Awitz tattoo 7358. No name known. Speaks Hungarian. nonresponsive to questions placed in care of UNRA. June 1945, UNRA, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, had taken custody of thousands of displaced children. After the war, Sarah contacted UNR’s successor organizations and searched their archived records.

In September 2024, she found it. A transfer document dated June 18th, 1945. Child A7358, name unknown, transferred to Jewish children’s home, Paris, France, accompanied by survivor Eva Klene, nurse volunteer. The document noted, “Child exhibits severe trauma, does not speak, requires ongoing medical care and psychological support.

” Sarah now had a location and a date. She contacted the organization that had run the Jewish Children’s Home in Paris in 1945. They had records. They had a name. The Jewish Children’s Home in Paris had operated from 1945 to 1952, caring for approximately 400 Holocaust survivor children who had lost their families. The organization’s records had been preserved and donated to the memorial dlesoa in Paris.

Sarah contacted the archivist who searched the 1945 intake records on September 15th, 2024. Sarah received an email with scanned documents attached. Intake record June 22nd, 1945. Hannah Goldberg, approximately age 6, from Monach, Hungary. Avitz, prisoner A7358, liberated from Bergen Bellson. No known surviving family.

Child is severely malnourished. Has tuberculosis. does not speak. Tattoo on left forearm placed in medical ward. Sarah had a name, Hannah Goldberg. The file contained additional records documenting Hannah’s recovery over the following months. July 1945. Hannah remains nonverbal. Responds to her name. Shows fear of adults but accepts comfort from female caregivers.

September 1945. Hannah has begun speaking in Hungarian. Asks repeatedly for Anya, mother. Has nightmares. Requires constant supervision. December 1945. Hannah’s physical health improving. Tuberculosis treatment ongoing. Psychological trauma remains severe. She has formed attachment to Eva Klene, staff member. March 1946.

Hannah has begun to play with other children. Still experiences severe anxiety. Refuses to let go of her doll, the one given to her at Bergen Bellson. She carries it everywhere. The doll in the photograph. Sarah realized the doll in the 1945 photograph had become Hannah’s security object.

Her connection to the moment of liberation, perhaps the first gift she received after surviving the camps. The records showed Hannah kept that doll with her for years. What happened to Hannah? Sarah traced Hannah’s life through the available records. 1946 to 1948. Hannah remained at the Jewish children’s home in Paris.

Eva Klene, the nurse who had brought her from Bergen Bellson, became her primary caregiver. 1948, Hannah was legally adopted by Eva Klene, who had lost her own family in the Holocaust. Ava was a Polish Jewish survivor who had survived Achvitz as an adult and dedicated herself to caring for survivor children. 1949, Eva and Hannah immigrated to the United States, settling in New York City.

1950s to 1960s. Records became sparse, but Sarah found evidence that Hannah attended public schools in New York, lived with Eva, who never married and devoted her life to raising Hannah, and completed high school. 1970 Sarah found a marriage record Hannah Goldberg married David Rosenberg in New York 1972 1975 1978 birth records for three children Rebecca Sarah and Jacob Rosenberg 1985 Sarah found something remarkable a newspaper article from a New York Jewish community publication Hannah Goldberg Rosenberg had given a

testimony at a Holocaust remembrance event. The article quoted her, “I was 6 years old when I was liberated from Bergen Bellson. I don’t remember my parents’ faces. I don’t remember home in Hungary. I remember the camps. I remember hunger. I remember fear. But I also remember the day I was given a doll, the first toy I had received in over a year.

That doll represented hope, kindness, the possibility that the world could be good again. I kept that doll my entire life. I showed it to my children. I told them, “This is what hope looks like.” Sarah’s next step was to determine if Hannah Goldberg Rosenberg was still alive. and if so to contact her or her family.

She searched public records, obituaries, and genealogy databases. What she found? Hannah Goldberg. Rosenberg had lived in New York until 2018 when she moved to a retirement community in Florida. She was 84 years old in 2024. She was alive. Sarah faced a difficult decision. Contacting Holocaust survivors about their past required extreme sensitivity.

Many survivors had spent decades building lives, raising families, and trying to move forward. Unexpected contact about their trauma could be deeply distressing. But Sarah also knew that many survivors wanted their stories documented. They wanted their suffering acknowledged. They wanted the world to remember.

Sarah decided to proceed carefully. She contacted the Holocaust survivor services organization in Florida, explained the situation, and asked them to serve as intermediaries. The contact. In October 2024, a social worker from the survivor services organization met with Hannah. She explained that a researcher had found a photograph of her from 1945 and wanted to share it with her, but only if Hannah wished to see it.

Hannah agreed to meet with Sarah. The meeting on October 15th, 2024, Sarah traveled to Florida and met Hannah Goldberg Rosenberg in the community room of her retirement community. Hannah’s daughter, Rebecca, was present for support. Hannah was small with white hair and sharp eyes. She walked with a cane. On her left forearm, clearly visible, was the faded tattoo, a 7358.

Sarah brought a tablet with the digitized photograph. Mrs. Rosenberg, Sarah said gently, I want to show you a photograph taken in May 1945, shortly after the liberation of Bergen Bellson. The image shows a little girl holding a doll. We believe this girl is you. Sarah showed Hannah the photograph. Hannah stared at the screen for a long moment. Her daughter held her hand.

That’s me. Hannah said quietly. That’s the doll. Tears ran down her face. I haven’t seen a picture of myself from that time in 79 years. The camps didn’t take photographs for prisoners. My family had no cameras. I had nothing from that time except my memories and the tattoo and the doll. You still have the doll? Sarah asked.

Hannah nodded. Come. They went to Hannah’s apartment. From a closet shelf, Hannah retrieved a carefully wrapped box. Inside, protected by tissue paper, was the doll from the photograph. The same porcelain doll, now 79 years old. Its paint faded, its dress yellowed, but intact. I’ve kept her all my life, Hannah said.

I named her Hope. When I had nightmares, I held Hope. When I was scared, I held hope. When I had my own children, I told them Hope’s story that she was given to me when I had lost everything. That she represented the kindness that still existed in the world even after so much evil.

Hannah looked at the photograph again. That little girl in the picture, she had survived hell. She didn’t know if she would ever be safe again. But someone gave her a doll. Someone showed her kindness. And that kindness saved her life as much as the medical care did. The discovery of Hannah’s identity and the connection between the 1945 photograph and the woman who had survived transformed the historical record and provided closure to a 79-year mystery. The full story emerges.

Over the following months, Sarah worked with Hannah to document her complete story. Hannah’s family pre-Holoc born February 1939 Mach Hungary now Ukraine father Jacob Goldberg Taylor mother Miriam Goldberg seamstress brother David Goldberg age 8 in 1944 grandparents aunts uncles cousins extended family of approximately 35 people May 1944 The Goldberg family was forced into the Monach ghetto with approximately 14,000 other Jews.

On May 23rd, 1944, they were deported to Ashvitz. Arrival at Ashvitz. May 28th, 1944. During selection, 5-year-old Hannah was pulled from her mother’s arms for reasons unknown, perhaps an error, perhaps a momentary decision by an SS officer. Hannah was tattooed and sent to the children’s barracks rather than immediately murdered.

Hannah’s mother, father, brother, and most of her extended family were murdered in the gas chambers within hours of arrival. Survival at Ashvitz, June 1944, January 1945. Hannah survived in the children’s barracks through luck, the protection of older prisoners, and her small size which made her invisible in certain situations.

She was used occasionally for medical experiments, non-lethal but traumatic procedures testing pain tolerance and starvation effects. transferred to Bergen Bellson. January 1945. As Soviet forces approached Ashvitz, prisoners were evacuated westward. Hannah was transferred to Bergen Bellson in January 1945. She survived the death marches and the horrific conditions at Bergen Bellson for four more months until liberation.

Liberation and recovery. April June 1945, British forces liberated Bergen Bellson on April 15th, 1945. Hannah was found in the children’s section, severely ill with typhus and malnutrition. She recovered slowly over the following weeks in the British military hospital facility. The photograph showing Hannah with the doll was taken on May 12th, 1945, exactly 2 weeks before her sixth birthday, though she didn’t know her birthday at the time, having lost all sense of dates and time during her imprisonment. The impact. The United

States Holocaust Memorial Museum added Hannah’s complete story to their permanent collection. The 1945 photograph, now identified, became part of an exhibition titled Faces Found Identifying the Unknown Survivors. Hannah agreed to provide video testimony for the museum’s archive. At age 84, she shared her memories, fragmented and traumatic, but important historical evidence.

The message. In her testimony, Hannah said, “For most of my life, I was just a number, a 7358. The Nazis tried to erase my name, my identity, my humanity. They tattooed me with a number to mark me as property as less than human. But I survived. I reclaimed my name. I built a life. I had children and grandchildren.

The number is still on my arm, but it doesn’t define me. That photograph from 1945 shows a moment of transition between being a number and becoming Hannah again. Between being a victim and becoming a survivor, between having nothing and receiving something, a doll, a small gift, but it represented everything, hope, kindness, humanity.

I want people to see that photograph and understand every victim of the Holocaust was a person with a name, a family, a story. We were not just numbers. We were human beings. And those of us who survived have an obligation to tell our stories so the world never forgets. The doll.

Hannah donated the doll, Hope, to the Holocaust Memorial Museum. It now sits in a display case next to the 1945 photograph with a placard explaining this doll was given to Hannah Goldberg Awitz prisoner a -7358 shortly after liberation from Bergen Bellson in May 1945. She kept it for 79 years as a symbol of hope and humanity’s capacity for kindness even in the darkest times.

Hannah’s family. Today, Hannah has three children, eight grandchildren, and five greatg grandandchildren as of 2024. Her extended family, all descended from a six-year-old girl who survived Achvitz, numbers over 30 people. At a family gathering in November 2024, Hannah’s greatgranddaughter, age six, the same age Hannah was in the photograph, asked to hold the photograph.

“That’s you, great grandma?” she asked. “Yes,” Hannah said. “You look sad.” I was very sad then. But see the doll? That doll gave me hope. and hope is what helped me survive to become your great grandmother.” The little girl studied the photograph carefully. “Can I see your number?” Hannah held out her left arm, showing the faded tattoo, a 7358.

The child gently touched the numbers. “Does it hurt?” “Not anymore,” Hannah said. It used to hurt every day, but now it’s just a reminder that I survived.