October 28th, 1945. Camp Holloway, Minnesota. The scrape of the metal ladle against the bottom of the soup pot was the only sharp sound in the low ceiling messaul. Outside, a persistent autumn drizzle tapped against the window panes, blurring the view of the barracks. Anelise kept one hand on the worn table, feeling the grain of the wood, the other resting near L’s elbow.

The younger woman flinched when the door opened, letting in a gust of damp, cold air and a new guard they did not recognize. He was young, his face still holding a softness the war had not yet scoured away. A neatly printed sign in both German and English was posted by the door. Orderly conduct is expected at all times.

He did not speak, merely took his post. His presence a silent reminder of their status. L’s breathing was shallow. Anelise leaned closer, her voice a near whisper. Assist in Ordnung, she murmured, her eyes on the guard. He is just watching. Stories like these found in the quiet corners of history reveal how understanding can begin in the most unexpected places.

6 weeks earlier, Main Street, New Olm, Minnesota. The rumor arrived with the autumn rain, a persistent whisper that spread through the damp air of barracks sea.

It was a flimsy thing, easily dismissed, yet it clung to the women like the chill that seeped through the wooden planks. A trip outside the wire into the nearby town of New Olm. Anelise heard it first from Gazella, whose bunk was nearest the door, and who seemed to catch every stray word carried on the wind.

“They say the Americans will take a few of us to see a shop,” Gizella had said, her voice low with a mix of excitement and disbelief, to practice our English. “Anelise,” mending a tear in L’s thin wool sweater, did not look up. “They say many things, Yuzella. They say the war will be over by Christmas. They said that last year, too. Her needle moved with a steady, practiced rhythm.

Hope, she had learned, was a dangerous ration. It was better to live on the predictable sustenance of routine, the morning roll call, the watery soup, the long gray afternoons. L, however, was listening, her eyes wide. A real shop with things to buy. We have no money, little one, Anelise reminded her gently, and there is nothing to buy.

Their shops are as empty as ours were. It is wartime. She nodded the thread and snipped it with her teeth. She had seen the posters in France before her field hospital was overrun. Buy war bonds, victory gardens, rationing is a weapon. She knew the language of scarcity, but the rumor persisted. It grew stronger when the camp commandant, a stern but not unkind major, requested a list of women with a basic grasp of English.

Analise’s name was on it, as was Les. A week later, they were assembled in the small administrative building. The air was thick with the unfamiliar smell of American coffee. The major stood before them holding a piece of paper. He explained the program. It was an educational initiative, he said, sanctioned by the town’s mayor, and in accordance with the articles of the Geneva Convention concerning the intellectual and recreational pursuits of prisoners of war.

He spoke of fostering understanding. One woman near the back scoffed quietly. Propaganda. Analise felt a flicker of the same cynicism. It was a performance. Then they would be shown a carefully curated display, a Potmpkin village shop, to demonstrate a prosperity that couldn’t possibly be real.

Still, a crack had appeared in the wall of her certainty. The major read the rules, no speaking to locals, no deviating from the group, absolute compliance with the guard’s instructions. Any infraction would terminate the program for everyone. Then he read the names for the first excursion. Annalise Schmidt, Lar. Her own name felt foreign in his American accent.

L gripped her arm, a small convulsive movement of pure joy. Anelise looked at the younger woman’s face, so pale and thin, and felt the familiar weight of responsibility settle upon her. She would go, she would keep Lada safe from disappointment. She would watch and she would listen and she would see this strange American theater for what it was.

But as she walked back to the barracks under the drizzling sky, a sliver of curiosity, sharp and unwelcome, had taken root. She was going outside the wire. The morning of the excursion dawned cold and clear. The rain had passed, leaving behind a sky the color of pale porcelain.

A nervous energy, thin and sharp, cut through the usual morning lethargy in barracks C. The women selected for the trip dressed in silence, their movements quick and deliberate. There was no chatter, only the soft rustle of clothing and the quiet splash of water in the wash basins. They were led once more to the small administrative building. This time their guard was waiting for them. He was not the major, but a young man whose uniform identified him as a corporal.

He had a map of the town spread on the table before him, and he looked up as they filed in, his expression neutral. He introduced himself as Corporal Miller. “All right, listen up,” he began, his voice flat, devoid of either malice or warmth. It was the voice of a man reciting a script he had memorized.

You will walk in a single file from the truck to the store. You will stay with me at all times. You are not to speak to any local person. If a local speaks to you, you will not respond. You will look at me. I will handle it. He paused, letting his eyes drift over their faces, ensuring the words were sinking in. Analise watched him closely. He could not have been much older than 20.

There were faint lines of fatigue around his eyes. She thought of the boys she had nursed back in Germany, boys who had been sent to the front with that same look of weary duty. The thought was disarming. He was not a monster. He was a functionary. You will not touch any merchandise, Miller continued. This is an observation tour only.

You will be inside the grocery store for approximately 20 minutes. Then you will walk back to the truck. Any deviation from these rules? He looked at each of them again and the program is over for good. Do you understand? A few hesitant nods. Anelise gave a single firm nod for both herself and L. The turning point was subtle.

Miller sighed, a small, almost inaudible sound as he folded the map. He looked less like a guard and more like an older brother tasked with a chore he found tedious. “Just follow me, stay quiet, and we’ll all get through this,” he said, his tone shifting slightly, becoming less official. It was not a threat, nor was it an offer of kindness. It was a simple statement of mutual interest.

Before they left, a pile of folded clothes was placed on the table. They were simple cotton dresses, clean and pressed, but clearly secondhand. The colors were faded blues and grays, a civilian uniform to replace their campissued one. Analise took one. The fabric was rough, but it was different. It was the fabric of an outside world she had almost forgotten.

She exchanged a glance with L. There was no turning back now. The back of the transport truck was dark and smelled of gasoline and damp canvas. The women sat on hard wooden benches that ran along the sides, their knees almost touching. No one spoke. The engine turned over with a rough cough, then settled into a low rumble that vibrated through the floorboards, a physical sensation of departure.

Annalise sat beside L, whose hands were clenched tightly in her lap, and placed a steadying hand on her arm. Through the gaps in the rear canvas flap, the world outside appeared in fleeting, disjointed frames. First, the familiar gray barracks and the sharp geometry of the wire fences fell away.

Then, trees, tall, skeletal autumn trees lining a dirt road. The truck picked up speed, its tires crunching over gravel, the rhythmic jolts, a constant reminder of their movement into an unknown space. Analise forced herself to look. She had expected. She did not know what she had expected. But it was not this.

The landscape that unfolded was one of vast quiet order. Endless fields of harvested corn stretched to the horizon. the cut stalks like a disciplined army standing at rest. She saw a large red barn, its paint bright and whole, not peeling or pockmarked by shrapnel. There were no blackened ruins, no craters filling with rain, no sense of a world holding its breath in fear. This land knew nothing of the war.

The truck slowed to cross a small bridge, and it was then that she saw it. Set back from the road was a white farmhouse with a thin plume of smoke rising from its chimney. In the yard, a woman was hanging white sheets on a clothesline, the fabric billowing in the crisp breeze. Near her, a small child, barely old enough to walk, toddled through the grass, chasing a barking dog. The sight struck Anelise with the force of a physical blow.

It was so profoundly normal, so utterly peaceful that it felt like a fantasy. She thought of her sister’s children in Dresden, of the games they played in rubble strewn streets before the sirens began. A wave of guilt, cold and sharp, washed over her. Why is their world so whole while ours is shattered? It was a question with no answer, and it left an ache in her chest that was worse than hunger or cold.

The rumble of the tires changed as they moved from gravel to a smooth paved surface. The truck made a slow, wide turn. New sounds filtered in. The distant chime of a bell, the low hum of another automobile passing. Analise could smell baked bread on the air. The truck stopped. The sudden silence was jarring.

After a moment, Corporal Miller’s silhouette appeared at the back, and he pulled the canvas flap aside, letting in a flood of bright morning light. “We’re here,” he said. Analise blinked, her eyes adjusting. Through the opening, she saw a clean sidewalk, a red brick facade with large plate glass windows, and neatly painted gold letters above them that read, “Henderson’s Grocery.

” Stepping down from the truck onto the solid pavement of Main Street was a disorienting act. For a moment, Anelise felt unsteady, her legs accustomed to the soft earth of the camp. The air was different here, carrying the faint sense of car exhaust and something sweet from a nearby bakery.

She was acutely aware of the few passers by, their gazes lingering on the small group of plainly dressed women escorted by a soldier. She pulled the collar of her borrowed dress closer to her neck and kept a firm grip on L’s elbow. Corporal Miller led them to the entrance. An automatic door swung open with a soft whoosh and a wave of warm, fragrant air washed over them. Analise flinched.

The light inside was intensely, unnaturally bright, a stark white glare from long tubes on the ceiling that made her blink. The world she had just left was one of muted grays and browns. This was a world of overwhelming color and light. They took a few hesitant steps inside and stopped, frozen just past the threshold.

L made a small sound, a choked gasp, and Analise’s grip tightened on her arm. It was not one single thing that caused the paralysis, but the totality of it, the sheer impossible scale. To their right stood a long, gleaming line of what looked like metal baskets on wheels. They were nested together, a silver serpent waiting patiently. Analise had never seen such a thing.

In Germany, a shopper brought their own string bag or wicker basket, one small enough to carry what little was available. These contraptions, these metal shopping carts, implied a different kind of gathering entirely. They were built for bulk, for a harvest. As her eyes adjusted, the rest of the space came into focus.

It was not a shop. It was a cavern. Isisles stretched away from them, longer than the barracks, longer than anything she could have imagined. Everything was ordered, stacked, and gleaming under the fluorescent lights. The low steady hum of refrigeration units was a constant unfamiliar sound. Latt was trembling beside her. Anelise, she whispered, her voice thin with panic. I cannot.

Acting on pure instinct, Anelise stepped forward and pulled one of the eggy metal carts from the line. It separated with a satisfying clatter. She gripped the handlebar, her knuckles white. The metal was cool and smooth beneath her fingers. It was a solid, real thing in this overwhelming dreamscape.

Its weight, the slight resistance of its wheels on the polished floor. It was an anchor. She took a slow breath. I am here. This is real. She looked up past the empty basket of the cart, and her mind struggled for a comparison. This is not a store for people, she thought with a dizzying sense of dislocation. It is a warehouse, a supply depot for a battalion.

Corporal Miller glanced back, his expression unreadable. He gave a slight jerk of his head, a silent command to move forward. Analise pushed the cart, its wheels rattling quietly, and guided Lau with her into the mouth of the first aisle. Anelise pushed the empty metal cart yu all forward, its wheels making a soft rattling sound on the polished lenolum floor. The first aisle was dedicated to soap. She stopped, mesmerized.

It was not the quantity alone that was shocking, but the variety. There were bars of soap and green wrappers, blue wrappers, white rappers, powders in tall, colorful boxes promised whiter whites, brighter colors. Back home, there was one kind of soap, a harsh yellow bar that smelled of lie and served every purpose from washing clothes to washing bodies.

Here there was a soap for everything, a specific solution for every imaginable need. They continued, moving as if in a transpass towering walls of canned goods, their paper labels bright and optimistic. Peas, corn, beans, peaches, stacked with military precision, they represented more food than Anelise had seen in one place in 5 years.

Her mind, the mind of a nurse trained to calculate rations and manage scarce resources, tried and failed to quantify what she was seeing. This was not a nation struggling through a war. This was a nation feeding itself without a second thought. Then they turned the corner at the end of the aisle.

Annalise stopped so abruptly that Lada bumped into her. Before them was the back wall of the store, and it was refrigerated. A long glass case ran its entire length, humming with a low electric pulse. This was the dairy counter. It was a wall of white and yellow.

Hundreds of glass bottles of milk stood in neat rows, their paper caps pristine, cold condensation beating on their sides. Next to them were blocks and tubs of butter stacked like gleaming gold bricks. There were cheeses of all shapes and sizes and dozens upon dozens of eggs nestled in cardboard cartons. Annalise stared, her throat tight.

Milk, real milk, was a luxury reserved for infants and the critically ill. Butter was a memory, a ghost of flavor from a time before the war. Here it was not a ration. It was a landscape. It was too much for Lada. Her eyes filled with tears. Anelise guided her away towards a quieter aisle filled with jars. That was where L stopped again, her hand flying to her mouth.

She pointed a trembling finger at a small glass jar filled with a deep red preserve. Chunks of fruit visible within. Maktat, she whispered, the German words fragile in the air conditioned stillness, just like my mother used to make. It was a simple, devastating observation. This jar of strawberry jam was not an abstract symbol of American power.

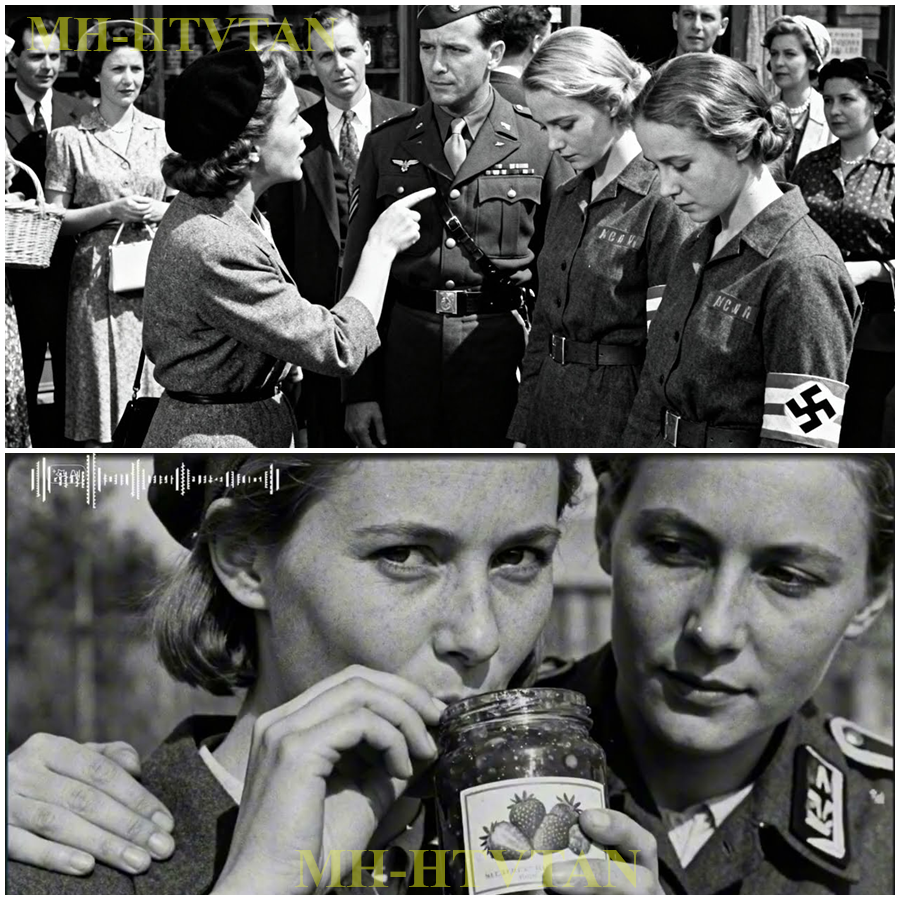

It was a direct, piercing link to a home that felt further away than ever. Anelise put an arm around the young woman’s shaking shoulders, shielding her from view. In that small private moment of shared grief and memory, she became aware of a new presence. She looked up from comforting L and saw another shopper, an older woman with sharp eyes and a tightly set jaw, staring directly at them.

Her expression was not one of curiosity. It was one of pure cold anger. The woman took a determined step in their direction. The woman’s shoes made a determined angry sound on the floor as she closed the distance. She ignored Anelise and L, directing her fury squarely at their escort.

Corporal, she said, her voice sharp and loud enough to cut through the store’s ambient hum. What is the meaning of this? My husband runs the Bond drive. We have a Blue Star flag in our window. Why are they here shopping like decent folk? Anelise froze, her arm a rigid bar around L’s shoulders. She instinctively shifted, placing herself more fully in front of the younger woman.

She dropped her gaze to the floor, focusing on the black scuff marks on the lenolium. Do not speak. Do not look at her. Look at the guard. The rules were a litany in her head. To disobey was to invite disaster. Corporal Miller stepped forward, positioning himself calmly between the woman and his charges. Ma’am, they are under my direct supervision. This is an authorized educational tour.

Educational? The woman scoffed, her voice rising. My boy is over there in the Arden right now fighting in the snow. What education do they need other than how to lose a war? The personal venom in her words made the air crackle. A few other shoppers had stopped their carts. Their curiosity peaked. Annalise could feel their stairs like physical weight.

The controversy surrounding the local P work programs was not just theoretical. It was now standing 3 ft in front of her. Before Miller could formulate a reply, a man in a crisp white apron appeared at the end of the aisle. He was tall and balding with a gentle expression that was now clouded with concern. “Mrs.

Gable, is there a problem here?” he asked, his tone even and respectful. “There certainly is, Mr. Henderson,” she retorted, gesturing with her thumb towards Anelise. “I don’t pay good money to shop for groceries alongside the enemy. The manager, Mr. Henderson, gave a small, polite sigh. He did not look at the prisoners. He kept his focus entirely on his customer.

Ma’am, I understand your concern. Truly, I do. But this is an official arrangement with the mayor’s office and the camp authorities. They are only observing. They are not permitted to purchase anything. He spoke not an apology, but as one stating an unchangeable fact. He was not defending the women. He was upholding a rule. Faced with the combined quiet authority of the store and the army, Mrs.

Gable was left without recourse. Her anger, finding no purchase, seemed to deflate, leaving behind a residue of bitter resentment. She shot one last venomous glare at Anelise, then turned with a huff, pushing her cart away with such force that a can of beans rattled against its metal frame. A heavy silence descended on the aisle. Mr.

Henderson gave Corporal Miller a small, almost imperceptible nod, then retreated toward the front of the store. Miller waited a beat, then spoke in a low, controlled voice, “All right, let’s move to the front. Anelise let out a breath she hadn’t realized she was holding and gently urged Lada to walk.

The immediate danger had passed, but the woman’s words hung in the air, a stark reminder that even in this land of impossible plenty, the war was not as far away as it seemed. Corporal Miller led them towards the front of the store, away from the lingering tension in the aisles. Here, near the large glass windows, were the checkout lanes.

Several were open, manned by young women in matching smoks, who moved with an easy, practiced efficiency. Analise and the others stood quietly to the side, watching the mundane spectacle as if it were a theatrical performance. A customer, a farmer in clean overalls, was unloading his cart. bread, a sack of flour, cans of coffee, a large piece of meat wrapped in white butcher paper.

The cashier, a girl with bright red lipstick, greeted him with a smile. She took each item, her fingers flying across the keys of a large, ornate machine that sat on the counter. Anelise found herself mesmerized by this machine. It was a solid mechanical beast of black metal and gleaming chrome. With every item, the cashier would press a series of keys, each producing a firm, satisfying clack. The numbers would appear behind a small glass window.

When she was finished, she pushed a large button on the side. A drawer shot open with a cheerful bell-like ding, revealing neat stacks of paper, money, and coins. The machine made a soft worring noise, and a narrow strip of paper emerged from the top. It was a machine of incredible order and finality.

It translated goods into numbers, numbers into a total, and a total into a clean, finished transaction. It was the sound of a society functioning on trust and systems, a world away from the grim, silent exchange of a ration coupon for a loaf of dense gray bread. Here they were complete outsiders, ghosts watching the living perform the simple rituals of their existence. Mr.

Henderson must have noticed their captivated stairs. He was standing at an empty checkout lane nearby, wiping down the counter. He caught Anelise’s eye and offered a small, sympathetic smile. He gestured for them to come closer. Anelise glanced at Corporal Miller, who gave a slight permissive nod. They approached the empty lane cautiously.

“A marvel of modern engineering, isn’t it?” Mr. Henderson said quietly, patting the top of the cash register. Without another word, he reached over and pressed a few keys at random. Clack, clack, clack. He then turned a crank on the side of the machine. The drawer did not open, but the bell gave its bright ding, and a fresh slip of paper spooled out. He tore it off with a crisp rip. He held it out to Anelise.

“A souvenir,” he said, his eyes kind. “For your English class.” Anelise was stunned into silence for a moment. She reached out and took the small piece of paper. It felt surprisingly solid in her hand, still warm from the machine. It was an act of simple, profound decency. He saw them not as the enemy, not as prisoners, but as women who were part of an English class. “Thank you,” she said. The words quiet but clear.

It was the first time she had spoken to an American civilian. She looked down at the paper, a column of meaningless numbers next to a list of generic department keys. It meant nothing and everything. She folded it once, then twice with meticulous care, and tucked it safely into the pocket of her dress.

“Time to go,” Corporal Miller said. The performance was over. The automatic door swished shut behind them. the sound sealing them out of the world of light and abundance as definitively as a cell door clanging shut. They walked back to the truck in a column, their feet silent on the pavement.

The afternoon sun felt warm on Anelise’s face, but the world had illuminated now seemed strangely muted. The colors less vibrant than those inside Henderson’s grocery. They climbed back into the familiar gloom of the transport truck. The engine rumbled to life, and with a lurch they were moving, leaving Main Street behind. If the ride into town had been filled with a nervous, quiet anticipation, the ride back was steeped in a thick, contemplative silence.

There were no words adequate to describe what they had just witnessed. It was too large, too profound. Each woman was an island lost in her own turbulent thoughts, trying to reconcile the memory of endless aisles with the reality of their barbedwire world. After several minutes on the road, Anelise felt a tentative touch on her sleeve.

She turned to see Jazella looking at her, her eyes asking a silent question. Anelise understood. She reached into her pocket and carefully withdrew the folded piece of paper given to her by Mr. Henderson. She unfolded the receiver and passed it over. The slip of paper began a reverent journey around the truck bed.

It was passed from hand to hand, held with a care usually reserved for a photograph or a letter from home. Fingers traced the crisp mechanical letters. B R E A D M I L K B U T T E R. They were no longer just vocabulary words from a lesson book. They were artifacts from another reality imbued with the weight of everything they represented. Full shelves, happy children, a world not consumed by hunger and loss. The receipt finally reached L.

She held the small paper in both hands as if it were a prayer card. her gaze fixed upon it. Outside the Minnesota farmland rolled by, the long shadows of late afternoon stretching across the harvested fields. At last, Lada looked up, her eyes meeting Anelise’s. They were startlingly clear, the fear and shock replaced by a dawning, fragile certainty.

“Anelise,” she said, her voice barely a whisper, yet carrying through the entire truck. Perhaps peace is real. The statement was so simple, so pure, it struck Anelise with more force than Mrs. Gable’s anger. L wasn’t speaking of treaties or surreners. She was speaking of the fundamental state of being. They had just glimpsed.

A world where peace was not the absence of war, but the presence of groceries. Anelise felt the last of her cynical armor crack and fall away. What weapon was more powerful than this? What propaganda could ever compete with the simple, devastating truth of a full shelf of strawberry jam? The truck slowed, the engine’s gear shifting down with a familiar wine.

Through the gap in the canvas, Anelise saw the stark silhouette of a guard tower against the setting sun. The wire fences of Camp Holloway came into view. They had arrived. The place they had called home for months now seemed alien and temporary, a gray dream from which they had briefly, shockingly awoken.

A few evenings later, the women gathered in the common room that served as their makeshift classroom. The air was cold, smelling of damp wool and chalk dust. A single bare bulb hanging from the ceiling cast long shadows against the rough wooden walls. The usual lethargy was gone. replaced by a palpable curiosity directed at Anelise and the small group who had gone into town.

Fraers, an older woman who had been a university librarian and now served as their volunteer English teacher, gestured towards Anelise. Tonight, she said, her voice gentle. Anelise will lead our lesson. She will share what she observed. All eyes turned to Anelise.

She walked to the front of the room, the small folded receipt feeling impossibly large in her hand. She unfolded it and held it up. On the small scarred blackboard, she carefully wrote the English word receipt t. This is a receipt, she began, her voice sounding formal and stiff. It is a list of things from the store. For example, she pointed to the first item, milk. M I L K.

She tried to continue to treat it as a simple vocabulary exercise, but the words felt empty, utterly stripped of their power. She saw polite incomprehension on the faces before her. How could she explain what a wall of milk bottles looked like to women who measured milk in spoonfuls? The words were ghosts, disconnected from the vibrant, overwhelming reality they were meant to represent. She stopped.

She put the piece of chalk down on the ledge, a cloud of white dust rising from the small impact. No, she said, her voice changing, becoming softer, more personal. That is not the lesson. She looked away from the blackboard and met the eyes of the other prisoners.

The lesson is not the words, it is the place. She paused, gathering her thoughts, abandoning the structure of a teacher and becoming a storyteller. The light, she began, you must first understand the light. It was white and everywhere, like daylight in the middle of a room. There were no shadows. She described the aisles, using her hands to show their impossible length and height.

aisles of soap, not one kind, but dozens. Cans of fruit stacked higher than a man’s head. Not for a week or a month, for a year, perhaps, for a lifetime. The room was utterly silent now, the women leaning forward. She was no longer just listing items. She was rebuilding the world she had seen.

She described the sounds, the rattle of the metal cart, the cheerful ding of the cash register. She spoke of the wall of butter like bricks of solid sunshine and the rows of milk bottles, like a battalion of peaceful white soldiers. Such educational and recreational activities were sanctioned, even encouraged to maintain morale. But no one could have predicted this.

As she spoke, she felt the last of her own guarded cynicism dissolving. She was not just recounting a memory. She was offering a testimony. She was giving these women a gift more precious than anything on the receipt, a tangible, believable vision of a world after the war, a reason to endure. When she finished, no one spoke.

The silence was not empty. It was full of thought, of wonder, of a hope so fragile it could be broken by a single word. After a long moment, Anelise walked over to the plank wall that served as their bulletin board. With a single metal thumbtack, she pinned the small receipt to the wood.

It hung there under the dim glow of the light bulb, a tiny miraculous document, not a list of groceries, but a map to a place called peace. Late that night, long after the final coughing fits had subsided and the barracks had settled into the deep rhythmic breathing of sleep, Anelise moved.

She sat up in her narrow bunk, pulling a thin wool blanket around her shoulders to create a small tent of privacy. From a hollowedout section in a thick German novel, she retrieved her journal and the stub of a pencil. In the faint flickering light of a secreted candle, she opened the book to a fresh page. She wrote the date, then paused, the pencil hovering over the rough paper.

How could she commit such an enormous, worldaltering experience to these small, cramped lines, her report of the trip was done. Her lesson in the classroom was finished. This now was for her alone. She began to write not about the items themselves, but about the effect they had created. She wrote of the quiet faces of the women as they listened to her story, of the way the small paper receipt now hung on the wall like a holy relic.

She tried to dissect the nature of the power she had witnessed. It was not the loud, brutal power of marching armies and roaring planes she had been taught to revere. It was something else entirely. Her pencil moved faster now, the words flowing as the core of her new understanding finally clarified itself. We were told they were a decadent nation, made soft by comfort and wealth, she wrote. We were taught that our sacrifice and our ability to endure hardship made us strong.

For a week, I have thought on this. I believe now it is the most profound mistake we ever made. They did not show us their weapons or their factories. They showed us a grocery store. And I now understand abundance is not propaganda. It is simply what peace looks like. She read the words back to herself. There it was.

A truth so simple and yet so powerful it had shattered her entire world view. She felt no anger, no bitterness, only a vast, quiet sorrow for all the lives wasted in pursuit of a flawed and broken idea of strength. A profound sense of peace settled over her, the kind that comes only after a long and terrible fever has broken. She closed the journal and tucked it back into its hiding place.

She blew out the candle, plunging her small space into darkness. Lying back on her lumpy mattress, she listened to the sounds of the sleeping camp. The future was a fog, her own fate tied to the slow, grinding conclusion of a war far away. But her fear was gone, replaced by a weary, lucid understanding. The men who guarded them were not demons.

They were just people from the other side of the door, the other side of the peace. She knew with a certainty that settled deep in her bones that weeks from now when a new guard with an unfamiliar face walked into the messaul, she would not feel the old reflexive spike of hatred. She would see a young man doing his job.

And when L flinched, Anelise would be able to put a hand on her arm and tell her with perfect honesty, as if he is just watching. It would not be a lie, nor simple reassurance. It would be the truth.