February 18th, 1945. No known 40 hours. US Army quartermaster depot Q117, Lady Island, Philippines. The diesel rumble hit her first, low, rhythmic, like a distant drum line muffled by humidity. Former Tatentai auxiliary Ayako my squinted under the tin roof awning as a GMC CCKW2, one two-tonon truck, lurched backward toward the loading bay.

The exhaust carried a sour blend of hot metal, burlap dust, and gasoline. An alien smell after years of bamboo camp kitchens and charcoal smoke. Ayako kept her hands clasped behind her the way the American sergeant had shown. No sudden movements. Stay visible. She wasn’t used to that either, being instructed with politeness instead of barked commands.

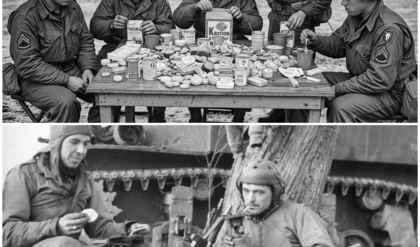

Sweat trickled down the inside seam of her repurposed herring bone twill shirt sticking to her ribs. A private and rolled up sleeves yanked a wooden pallet into alignment using a steel hand truck. A chocked label rations K component lot 291 scratched against her nerves. This abundance, this order, this impossible rhythm.

She had been taught allied logistics were chaotic. that Americans fought sloppily and survived only through luck. Then the foreman raised two fingers. The depot froze for a heartbeat. “Mark it! Seal it! Move it!” he barked. A whistle shrieked. The entire bay moved at once. Bales lifted, crates stacked, manifests stamped. A choreography of strangers.

Ayako’s breath hitched. “How could a nation with this lose?” 6 weeks earlier, camp number 21, Sama. 6 weeks before the depot, the rain in Samar fell in thin, persistent needles that turned the pathway between barracks into a gray slurry. A yakamorei stood beneath the sagging overhang of the women’s annex, clutching the frayed strap of her satchel as an American MP read names from a clipboard.

His pronunciation of Japanese syllables was careful, oddly gentle, but she felt her stomach nod anyway. The truck idled nearby, an Army WC51 weapons carrier, canvas top rattling in the wind. Diesel fumes curled toward her, mingling with the damp scent of moldy wood. She had never ridden in a foreign military vehicle.

The idea alone felt like betrayal. Mori Aayako, you’re on the list,” the MP said. She stepped forward, her sandals slurped against the mud. Inside the truck, two other women sat stiffly, eyes downcast. Ayako climbed in beside them, gripping the cold metal support bar as the engine shuddered to life. No one explained why they were being moved.

Transfer could mean reassignment, interrogation, or some administrative error. She remembered whispered rumors. Some prisoners were sent to labor detachments, others to translation units. The possibilities churned. As the truck bounced along the coastal track, she watched coconut palms flash by, their fronds slick with rain.

An American private offered cantens. She refused, unsure if acceptance would be misinterpreted. When they reached a small outpost, a civil affairs lieutenant approached with a folder of documents tied in cotton string. He spoke through a Japanese American interpreter. You three will assist with captured supply records.

The interpreter relayed clerical work only. Captured records. Ayako felt heat creep up her neck. Using her skills against Japan, against men still fighting, twisted something inside her. But the lieutenant’s posture was steady, business-like, not coercive. A new truck arrived, rumbling deeper and heavier than the last.

Destination stencled on its bumper. Q117. The moment she stepped aboard, she sensed the path ahead narrowing. Each jolt of the chassis carrying her toward a place where the war would look different, and none of her assumptions would remain untouched. The first thing Ayako noticed about Q17 was that it sounded like a factory trying to outshout a storm.

As the truck rolled through the open gate, the noise rose around her. diesel engines revving, men shouting over distance, the hollow thud of crates hitting wooden platforms. She stepped down from the tailgate and felt the ground vibrate under her sandals as another GMC CKW growled past, its canvas sides bulging with cargo.

Mud gave way to compacted gravel near the loading bays. under a long tin roof shed. Lines of wooden pallets sat like low square islands. Men in faded herring bone twill jackets, muscled crates onto them using steel hand trucks, wheels squeaking under the load. Ink smudged papers were pinned to clipboards, and every few seconds someone slammed an inked stamp down with a sharp final sound.

An American sergeant with three chevrons and a blocky jawline gestured for her group to follow. A Nissi interpreter walked beside him, boots crunching. This is quartermaster depot Q117, the interpreter said. They handle food, clothing, equipment for units on Laty and beyond. You won’t go near the front. Only paperwork. Only paperwork.

The words should have calmed her, but the scale of the place made her throat tighten. Trucks reversed to a whistle’s short blasts. On the long call, men froze, then moved as one. Pallets slid forward, crates changed hands, stamps came down. A pattern, not chaos, something else. They passed a bay where several crates stencileled in familiar Japanese characters waited apart from the rest.

Ayako’s eyes snagged on them. Kanji for rice, medical items, small arms parts. her past life reduced to foreign property. The sergeant stopped and pointed to a small office near the loading floor, windows clouded with dust. “You’ll start there,” the interpreter said. Captured Japanese supplies. “They need your eyes.

” The depot’s rhythm pressed in around her. “For the first time, she wondered if the real battle was happening here. Far from any gunfire, the office smelled of paper more than people. Not the thin fibrous sheets she knew from home, but heavier stock, war department forms layered under piles of captured documents.

A ceiling fan ticked lazily above, shifting the warm air just enough to blur the edges of ink. Ayako sat at a scarred wooden desk, a stack of Japanese quartermaster manifests on her left, American forms on her right. A pencil lay centered between them like a narrow gray bridge. Outside the thin wall, the thump of crates landing on pallets came at irregular intervals, each impact making the inkwell tremble.

A Ni corporal leaned over her shoulder, pointing to a faded line of kanji on the top sheet. “This column, original shipment origin,” he said in Japanese. “They want to know ports, roots, if possible. You don’t have to guess. Only what is written.” She nodded, tracing the characters with her eyes. Her own people’s handwriting now under foreign light.

The manifest listed field rations, spare parts, medical dressings. In the margin, an American officer had already penciled notes, approximate calorie count, estimated issue per platoon. They had been learning without her. On another sheet, a crate code she’d only seen in training reappeared. In the United States, far from Osaka or Yokohama, someone had already mapped it to a catalog number.

The corporal slid a cross reference sheet beside her, a neat table joining Japanese and American categories. You see, we already know some, he said. You help us make fewer mistakes. Fewer mistakes. For whom? A sergeant stepped in, boots dusting the plank floor, and set a small pair of calipers on the desk. If you’re unsure, the interpreter translated, measure what we can open. Compare with the manifest.

We check each other. The idea that Americans would use precise tools on Japanese crates unsettled her. Still, her hand closed around the cool metal. Hours later, when she turned in her first finished batch, the lieutenant flipped through the pages, then glanced up. “You work carefully,” the interpreter said for him.

“Tomorrow, you’ll see how all this moves. A floor tour.” The fan ticked on. Outside the depo roared, and now she was being invited into its bloodstream. They gave her a clipboard for the tour, though she had nothing to write. It felt like a prop to steady her hands. The lieutenant led the small group, Ayako, the nay corporal, two clerks, out of the office, and onto an elevated catwalk that crossed above the loading floor.

From up here, Q117 looked less like a yard and more like a moving diagram. CCKW trucks backed into bays at angles that seemed chaotic until she noticed the paint marks on the ground, the numbered posts, the way each driver lined up with a specific stencil. “Watch,” the corporal said quietly in Japanese, as if narrating a film.

A whistle blew. Two short blasts. Trucks halted. Men swung into action. Tailgates dropped. Pallets slid into place. Crates flowed down short wooden ramps. Another whistle, one long. The motion shifted. Empty pallets came back. Full ones rolled inward on hand trucks. On the far side, a second line of trucks waited to be loaded, engines idling.

On the wall opposite the catwalk hung a row of chalkboards, edges ghosted with old numbers. Fresh white marks showed columns labeled by unit designations she didn’t recognize. 24th division, 32nd division, and dates. Beside each tonnage figures marched down the board. 45 tons, 63 tons, 72. They supply several divisions from here, the corporal said.

food, ammunition, clothing. Each day she knew what a division required in theory. Seeing the numbers stacked, day after day, clawed at her chest. For every figure on the board, there were soldiers who would not go hungry, guns that would not fall silent. Below a clerk flipped a convoy timet, revealing departure hours, convoy numbers, destinations abbreviated into neat codes. Nothing at Hawk.

Everything written, checked, erased, rewritten. Ayako gripped the clipboard until her knuckles whitened. Back home, she had been told Americans were soft, improvised, dependent on luck. “But this, this was a machine made of paper, fuel, and time.” “Impressive, is it not?” the lieutenant asked through the interpreter, more as an observation than a boast.

She opened her mouth, then closed it. The word she wanted in Japanese, kawaii, frightening, didn’t fit the question. What she felt was not fear of men, but of arithmetic. For the first time, a thought she had never allowed in crept in, quiet as dust. What if we cannot win against this? The next morning, they put her closer to the noise.

Ayako stood at the edge of bay 3, clipboard balanced against her hip, copying crate numbers from a stack of captured Japanese boxes onto fresh American tags. The bay smelled of damp rope and spilled grain. Overhead, the tin roof pinged softly as last night’s rain dried in patches. Filipino laborers moved around her in USissue HBT shirts and mismatched trousers, sleeves rolled, skin glistening with sweat.

Their English orders came from an American corporal, but their conversations, sharp, quick to galog, slid past her. She heard her language only in the stencileled characters on the wood. A pallet jolted into place beside her, pushed harder than necessary. A man about her age, jaw tight, stared at the kanji on the crate and then at her armband marking her P status.

“You wrote those markings once, maybe,” he said in halting Japanese, surprising her. “For the people who came to my village.” His accent clipped the vowels, but the meaning landed clean. Ayako’s throat closed. She hadn’t been near any village burnings, any roundups, but she typed orders, filed requisitions, kept the system neat. Her pencil hovered useless.

She lowered her eyes to the wood grain. I only did office work, she murmured, hearing how weak it sounded, even to herself. The man took a half step closer, weight shifting on the boards. Office work sent men with rifles, he replied. Before the air could thicken further, a shadow fell between them. A staff sergeant, sleeves rolled, clipboard in hand.

“That’s enough,” he said, voice flat. The nay corporal translated, adding nothing. The sergeant looked from the Filipino worker to Ayako, then tapped a posted sheet by the bay entrance. Red Cross inspection rules and depot conduct orders tacked under a thumbtack. Everyone works. No one touches the prisoners. No one harasses the civilians. That’s the rule here.

The Filipino man held the stair a heartbeat longer, then grabbed the pallet jack handle and yanked the load forward. As it rolled away, Ayako realized her hands were shaking. The sergeant didn’t soften his tone when he turned to her. “Keep your tag straight,” the interpreter relayed.

“Convoys don’t wait because people argue.” She nodded, forcing her pencil back to the paper. Around her, the depot’s rhythm resumed, but now each thud of a crate sounded like something dropped between her and the world she’d once understood. The depot felt smaller when the schedule tightened. By midm morning, a new set of trucks had jammed the approach road, engines idling in a low, impatient growl.

A chocked note on the bayboard read, “Convoy 7. Advanced, the time underlined twice.” The whistles shrieked more often now, short, sharp bursts that snapped men into motion. Ayako stood at a narrow table near Bay 2, where rooting tags waited in neat stacks. Each stiff card carried a code, unit designation, priority, destination.

Her job was simple in theory. Copy crate numbers from manifests, match them to tags, clip them on before the pallets rolled. Simple until the world sped up. A CCKW backed in too fast, its tires spitting gravel. Crates thudded down a ramp onto a pallet right beside her, the top one stencled in Japanese. Sweat prickled between her shoulder blades.

Krations mixed,” the American clerk called, glancing at his sheet. “That stack goes to 24th Division. Tag them.” He slid a small bundle of routing tags toward her. Ayako scanned the kanji on the nearest crate. The characters were faded, but unmistakable. Concentrated medical rations, not standard field food.

The code aligned with what she’d translated days ago. These were meant for a different unit entirely. closer to a field hospital. She looked at the clerk’s form, a tiny pencil smear near the crate line, a transposed digit. One careless mark and an entire pallet would vanish into the wrong stream. Behind her, a whistle gave two quick blasts. Move. She could say nothing.

Let the mistake stand. Somewhere American soldiers, the enemy would wait longer for bandages and medicine. A small tilt on a massive scale. The Filipino worker from yesterday wrestled a pallet jack nearby, eyes sliding past her without expression. The staff sergeant stroed along the bay, watching hands, not faces.

A yako’s own hands hovered over the tags. The depot’s roar pressed in. whistles, wheels, shouted times. She imagined the chalkboards on the far wall, the tonnage columns, the timets, all of it depending on numbers being what they claimed to be. Her pencil touched the form. Carefully, she corrected the digit, then reached for the proper destination tag and clipped it to the crate.

24th? The clerk asked, half distracted. She looked up, voice steady. No, this one is for the medical detachment, she said in Japanese, letting the nay corporal translate. The manifest was misread. The clerk hesitated, then shrugged, correcting his sheet. The pallet rolled forward, sucked into the depot’s current.

Ayako watched it go, a knot tightening in her chest. Somewhere beyond the island, men she would never see might open those crates, and never know who had nudged their fate by a single line of graphite. The depot woke earlier on inspection day. By the time Ayako reached the loading floor, men were already tightening straps, sweeping stray nails from the bays, straightening stacks of routing tags on the tables.

A new board by the entrance bore chocked names and ranks, quartermaster officers, an inspector from higher headquarters. Besides some convoy numbers, a diagonal line, and the word priority cut through the chalk like a blade, whistles shrilled in short, rehearsed bursts as trucks rolled into place with unusual precision.

The noise felt sharper, as if even the engines understood they were being watched. Filipino workers moved with clipped efficiency, eyes flicking to the approaching officers in pressed khaki. Ayako stood where she had been assigned near bay four, clipboard in hand, reviewing manifests, already checked twice. Somewhere in the long procession of pallets was the medical stack she had rerooed yesterday.

A captain with silver bars on his collar walked the line with an inspection clipboard flanked by the staff sergeant and the nay corporal. They stopped at each pallet, check crate numbers, compare tags, mark a clean tick, or occur correction. When they reached the medical load, Ayako recognized the kanji before they did. The captain frowned at the top crate, then glanced at the routing tag.

This was originally marked for 24th, wasn’t it? He asked. The corporal translated the question toward her. Ayako’s mouth went dry. She nodded, explaining in Japanese. Faded characters, a misread code, her correction. The corporal relayed it calmly. The captain checked his earlier notes, then let out a short breath. Good catch, he said.

That would have fouled up a whole chain. Medical can’t afford that. The corporal turned to her. He says you prevented a serious mistake. His tone stayed neutral, but his eyes held something softer. As the pallet rolled away toward the staging area, the Filipino worker from Bay3 passed close by, hands on a jack handle.

He didn’t stop, but his gaze brushed hers, and he gave the smallest of nods, barely more than a twitch. It was not forgiveness, but it was recognition. Whistles blew again. Another convoy time shifted on the board. Officers moved on, satisfied enough to let the machine keep turning. Ayako remained where she was, the clipboard suddenly heavy.

Her graphite marks, her narrowed eyes over faded ink had just pushed unseen hands along distant front lines. The realization settled on her shoulders like an invisible pack she would carry long after the trucks departed. By late February, the depot’s rhythm had become a kind of second weather, always there, changing in small degrees.

Ayako could tell the time of day by the pitch of the engines outside the office, by when the shadows of the CCKW trucks stretched long across the gravel. That morning, humidity lay over Q117 like a warm, damp sheet. She stepped out from the office to carry a stack of updated manifest to bay 1.

The foreman stood on the loading dock. Whistle cord looped around his fingers. Cap pushed back. Ready on the line, he shouted. Diesel rumbled. A truck backed in, tires crunching over the packed surface. Ayako paused under the awning, the same spot where she had first felt the depot roar around her and watched as a pallet slid into place.

Bales were lifted, crates rotated and stacked. The air smelled of exhaust, burlap, and the faint metallic tang of spilled fuel. The foreman raised two fingers. For a heartbeat, everything held. “Mark it! Seal it! Move it!” he barked. The whistle shrieked. Men surged into motion. A clerk slapped manifest tags onto the pallet.

Another worker drove a hand truck beneath, wheels squealing as it rolled forward. From her vantage point, the scene looked almost identical to the first time she’d seen it. Same gestures, same rhythm, only she was different. The medical shipment she had corrected days ago was gone now, somewhere in the chain of islands and sealanes.

She would never know if the crates arrived in time, if bandages were unrolled in hurried tent hospitals because of a digit she’d changed. The war would not pause to inform a prisoner of clerical outcomes. The Nissi corporal approached, nodding toward the papers in her hands. “They want you to keep working on the captured manifests,” he said.

“New crates came in from another island. Same system.” Ayako looked down at the familiar Japanese characters on the top form, then back at the depot floor where American and Filipino hands moved and practiced arcs. “All right,” she said softly. “I will.” She did not think of it as helping an enemy or betraying her own. “Not anymore.

It was ink on paper, numbers aligned with destinations, food and medicine, following paths that men in uniforms had drawn long before she arrived. The war, she realized, was not only fought where bullets flew. It was here, too. In pallets and whistles, in quiet decisions made by people like her, standing in the shade of tin roofs, holding a pencil that could bend the line of a convoy by a fraction of an inch.

And in that narrow space between the crate and its destination, she found the only kind of control left to her. to see clearly and to write the truth of what was in front of her.