Dr. Elellanar Matthews adjusted her reading glasses as she carefully examined the sepia photograph that had arrived at the Royal Historical Society that morning. The image donated by an elderly woman clearing her late aunt’s attic in White Chapel showed two young boys embracing on what appeared to be a London street corner.

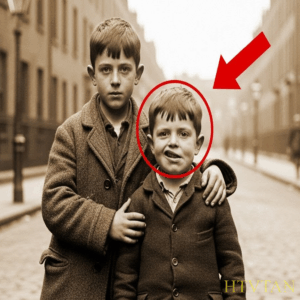

The faded inscription on the back read simply Thomas and William, autumn 1906. At first glance, it seemed like countless other family photographs from the Edwwardian era. two brothers in worn woolen coats, their faces serious despite the tender embrace. The older boy, perhaps 12, had his arm protectively around his younger sibling, who couldn’t have been more than eight.

But as Elellaner studied the image under her magnifying glass, something peculiar caught her attention. The younger boy’s mouth appeared oddly distorted, twisted in a way that seemed unnatural for such a posed photograph. His lips were pulled to one side, creating an asymmetrical expression that contrasted sharply with the formal nature of early 20th century portrait photography.

“How strange,” Eleanor murmured to herself, noting the precise way the photographer had captured every other detail. The cobblestones beneath their feet, the gas lamp in the background, even the delicate stitching on their clothing. Yet, this facial anomaly seemed deliberately preserved, as if it held significance beyond mere photographic accident.

The donor’s accompanying letter mentioned that the photograph had been kept in a locked drawer for nearly a century, discovered only when her aunt’s house was being cleared. No family member could recall ever seeing it before, despite its apparent importance to someone who had carefully preserved it through decades of London’s tumultuous history.

Elellanar felt the familiar thrill of historical mystery settling over her. In her 15 years of archival work, she had learned that the most ordinary objects often concealed the most extraordinary stories. This photograph, with its haunting embrace and mysterious facial distortion, seemed to whisper of secrets waiting to be uncovered.

Eleanor began her investigation the following morning by examining the photograph’s technical aspects. under ultraviolet light. She confirmed its authenticity. The paper stock and chemical composition matched other photographs from 1906. The image had been taken with professional equipment, suggesting it wasn’t a casual family snapshot, but something more deliberate.

She contacted the White Chapel Historical Archive, hoping to trace the photograph’s origins. Margaret Hartwell, the elderly donor, had provided an address. 42 Dorset Street, a location that immediately caught Elellaner’s attention. Dorset Street had been one of the most notorious slums in Victorian London. Known for its poverty and connection to the Jack the Ripper murders.

“The house belonged to my great aunt Sarah,” Margaret explained during their phone conversation. “She never married, lived alone until she passed last month at 97. Family always said she was secretive, kept to herself. We found this photograph wrapped in tissue paper. Locked away like it was precious. Eleanor decided to visit the White Chapel area, hoping to find records or neighbors who might remember Sarah or have information about the photograph subjects.

The November air was crisp as she walked down the modern Dorset Street, trying to imagine how it would have looked over a century ago. At the local parish church, St. Bulfs. She met with Father Michael, whose congregation included many families with deep roots in the area. He examined the photograph carefully, his weathered face growing thoughtful.

The younger boy’s expression, he said slowly. It reminds me of something. During my seminary training, we studied historical accounts of children with various conditions. “This doesn’t look like a photographic error. It looks like the child might have had some form of facial paralysis or birth condition.” This observation opened new possibilities.

Elellanena realized she might be looking at more than just a family photograph. She could be seeing documentation of a medical condition in an era when such differences often led to social ostracism. Eleanor’s next stop was the Royal London Hospital’s historical archive, where Victorian era medical records were meticulously preserved. Dr.

James Whitmore, the hospital’s medical historian, welcomed her with enthusiasm when she showed him the photograph. Fascinating, he murmured, studying the younger boy’s facial asymmetry through a magnifying glass. This appears consistent with what we now call Bell’s palsy or possibly a congenital facial nerve paralysis. In 1906, such conditions were poorly understood and often viewed with superstition.

Dr. Whitmore led Elellaner through the hospital’s archived records, explaining how children with facial differences were often hidden away by families or in severe cases institutionalized. The social stigma was enormous, he explained. Families sometimes went to great lengths to conceal such conditions.

believing they brought shame or were signs of moral failing. They discovered several admission records from 1906 1907 for children with similar conditions, but none matching the names Thomas and William. However, one entry caught their attention. A note about experimental treatments being offered for facial anomalies in indigent children by a doctor Adelaide Morrison.

Dr. Morrison was remarkable for her time, Dr. Whitmore explained. One of the few female physicians in London, she specialized in treating children others had given up on. She worked extensively in the East End, often providing care to families who couldn’t afford traditional medical attention.

Ellaner felt a surge of excitement. If Dr. Morrison had treated the boy in the photograph, there might be records of the family, their circumstances, and what had happened to them. The doctor’s practice notes, if they still existed, could provide the key to understanding not just the medical condition, but the story behind why this photograph had been so carefully preserved.

The trail was warming, but Eleanor sensed they were only beginning to uncover the deeper mystery surrounding these two brothers in their poignant embrace. On a London street over a century ago, Eleanor’s search for Dr. Adelaide. Morrison’s records led her to the women’s medical archive at the London School of Medicine.

The librarian Katherine Wells was intrigued by Eleanor’s inquiry and pulled several boxes from the restricted collection. Dr. Morrison’s papers were donated by her niece in 1967. Catherine explained she was quite revolutionary, treating children with facial deformities at a time when most physicians wouldn’t even examine them. Her approach was remarkably compassionate. Among Dr.

Morrison’s detailed case notes, Ellaner found records spanning 1904 to 1910 documenting treatments for dozens of children. The doctor’s handwriting was meticulous, her observations both clinical and deeply human. She had noted not just symptoms and treatments, but family circumstances, social challenges, and the emotional impact on both children and parents.

One case file dated September 1906 made Elellanar’s heart race. Patient W, age 8, facial nerve paralysis, left side, accompanied by older brother T, approximately 12. Father deceased, mother working in match factory. Children living in lodging house on Dorset Street. The initials matched, the age matched, the location matched.

Eleanor photographed the relevant pages, her hands trembling slightly with excitement. Dr. Morrison had written extensively about this case, noting the older brother’s protective behavior and the family’s desperate financial circumstances. Treatment progressing slowly. One entry read, “Patient shows remarkable courage despite social difficulties.

Brother T never leaves his side during appointments. Mother reports neighbors cruel comments about W’s appearance. Have discussed possible surgical intervention, but family cannot afford extended treatment.” The final entry dated November 1906 was heart-wrenching. Treatment discontinued. Mother can no longer afford to bring children to appointments.

W showed significant improvement, but full recovery unlikely without continued care. Gave mother exercises to continue at home. Both boys left today. T promised to care for his brother always. Eleanor realized the photograph might have been taken around this same time. Capturing a moment during their medical treatment period.

Armed with the information about the boy’s mother working in a match factory, Elellanar began researching the industrial conditions of early 20th century London, match factories were notorious for their dangerous working conditions, particularly for women who developed fsy jaw from exposure to white phosphorus. At the Tower Hamlet’s local history archive, Ellaner discovered employment records from Bryant and May, the largest match factory in the area.

The records showed a woman named Mary working in the factory from 1905 to 1907 living at an address on Dorset Street. The facto’s medical officer had kept detailed health records, noting concerns about workers children. One entry mentioned female employee widow supporting two sons, one with medical condition affecting speech and facial movement.

Eleanor’s investigation revealed the harsh reality faced by workingclass families in Eduwardian London. Mary earned barely enough to afford their single room in a lodging house, sharing the space with other families. The medical treatments for her younger son represented a significant financial burden, often forcing her to choose between medicine and food.

A breakthrough came when Elellaner found records from the local school board. Attendance records showed both Thomas and William enrolled sporadically at the Dorset Street Board School. The teacher’s notes revealed telling details. Thomas excellent student when present. Fiercely protective of younger brother William, who struggles with speech due to facial condition.

Other children sometimes cruel in their teasing. One teacher’s report dated October 1906 painted a vivid picture. Thomas shows remarkable maturity for his age, often acting as spokesman for his brother. William is intelligent but withdrawn due to his condition. The bond between these brothers is extraordinary. Thomas never allows anyone to mock William and has been known to fight children much larger than himself in his brother’s defense.

This context gave new meaning to the photograph’s embrace, suggesting it captured not just brotherly affection, but a profound protective relationship born from difficult circumstances. Elellanar’s research revealed that the family had disappeared from official records after 1907. No further school attendance, no medical appointments, no employment records for their mother, Mary.

It was as if they had simply vanished from documented London life. This pattern was unfortunately common among the poorest families of the era, who often moved frequently to avoid debt collectors or seek better living conditions. Elellaner expanded her search to workhouse records, knowing that many destitute families eventually sought refuge in these grim institutions.

At the White Chapel Union workhouse archives, she found a heartbreaking entry from January 1907. Admission of Mary, widow with two sons. Thomas, age 12. William, age eight. Mother suffering from industrial poisoning. Unable to continue employment. Younger child has facial paralysis.

The workhouse records painted a bleak picture. Families were separated by gender and age with children housed separately from parents. The boys would have been placed in the children’s ward while their mother recovered in the women’s medical section. Most devastating was a medical report dated March 1907. Mary, aged 29, died of complications from phosphorous poisoning.

Two orphan sons remain in workhouse care. Ellaner felt her throat tighten as she read the bureaucratic notation that marked the end of a family. The boys had lost their mother, the very person who had fought so hard to get medical treatment for Williams condition. The subsequent records showed Thomas and William were transferred to the Stephanie Orphanage in April 1907.

The intake notes described Thomas as mature beyond his years, refuses to be separated from younger brother despite different age classifications. Elellaner discovered that the Steppne orphanage had closed in 1958, but some records had been transferred to the Tower Hamlet’s archives. Her hands shook as she opened the file containing the boy’s information, knowing she was about to learn what became of the two brothers captured in that poignant 1906 photograph.

The Stephanie orphanage records revealed both heartbreak and hope in the boy’s story. Thomas and William had been placed in the institution under difficult circumstances, but the detailed notes kept by the staff painted a picture of resilience and unbreakable family. Bond’s matron Elizabeth Fairfax had written extensively about the brothers in her weekly reports.

Thomas continues to act as protector and interpreter for William. The younger boy’s facial condition makes speech difficult. But Thomas understands him perfectly and speaks for him when others cannot comprehend. Eleanor learned that the orphanage, while strict and austere by modern standards, was considered progressive for its time.

The staff made efforts to keep siblings together and provide basic education. Thomas excelled in his studies, while William showed remarkable talent in art and craft work. Despite his speech difficulties, one particularly moving report from 1908, described an incident where older boys had been teasing William about his facial paralysis.

Thomas, though smaller than his tormentors, fought with such fierce determination that the bullying ceased entirely. His devotion to his brother’s welfare supersedes all other considerations, including his own safety. The orphanage records also showed that Dr. Morrison had not forgotten her former patients.

She made monthly visits to check on Williams condition, providing continued exercises and monitoring his progress without charge. Dr. Morrison reports that William’s condition has stabilized. One note read, “While full recovery remains unlikely, the boy has adapted well. His brother Thomas continues to serve as his primary advocate and communication assistant.

Ellaner discovered that the photograph had likely been taken during their mother’s illness, perhaps as a keepsake before the family’s circumstances deteriorated completely. The embrace captured in the image represented not just brotherly love. But Thomas’s promise to always protect William, a promise he had clearly kept even after entering the orphanage system.

The records showed both boys had remained at Stephanie until 1914. when they would have been old enough to leave and make their own way. And the world do Ellaner’s research into the boy’s lives took a dramatic turn when she discovered their paths diverged upon, leaving the orphanage in 1914. Thomas, now 20, had found employment as a clerk with a shipping company in the London docks.

William, despite his facial condition affecting his speech, had been apprentice to a craftsman who specialized in fine woodworking. His artistic talents from the orphanage had served him well. The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 changed everything. Military recruitment records showed that Thomas had enlisted in the London Regiment in October 1914, driven by patriotic fervor and the promise of steady pay that he could send back to help his brother.

What Elellanar found next took her breath away. Among the military service records, she discovered that William had also attempted to enlist despite his facial condition. The recruitment officer’s notes were telling. Applicant rejected due to facial deformity affecting speech clarity. However, demonstrated exceptional skill with his hands and acute attention to detail.

Instead of military service, William had been directed to a government workshop producing precision instruments for the war effort. His condition, which had been a source of shame and difficulty throughout his childhood, had inadvertently saved his life by keeping him out of the trenches. Thomas’s military records showed he had served with distinction in France, participating in several major battles.

His letters, preserved in his personal file, consistently mentioned his brother. Tell William I am well and thinking of him always. Hope his work at the factory continues successfully. The most poignant discovery came in a Red Cross file documenting Thomas’s death at the Battle of the Psalm in July 1916. His final letter written days before the battle contained a request that stunned Elellanar.

Should anything happen to me, please ensure my brother William receives my personal effects. He is all the family I have and I his. The photograph of us as boys should go to him. It reminds us both of our promise to stay together always. Eleanor realized the photograph had been Thomas’s treasured possession, carried through years of separation and war.

Eleanor’s investigation into William’s life after his brother’s death revealed a story of quiet resilience and hidden strength. Military records showed that he had indeed received Thomas’s personal effects, including the photograph that Eleanor was now studying more than a century later. Through employment records and craft guild documentation, Ellaner traced Williams career as a skilled woodworker.

Despite his facial paralysis and speech difficulties, he had built a reputation for exceptional craftsmanship, specializing in intricate joinery work for churches and public buildings throughout London. A breakthrough came when Ellaner contacted St. Bartholomew’s Church in Stephanie, which had undergone restoration in the 1920s.

The church records mentioned William by name as the craftsman who had created their ornate choir stalls, noting his remarkable skill despite personal challenges. The church’s longtime vir, now retired, had kept detailed records of all restoration work. His notes revealed that William had been known for his perfectionism and his reluctance to speak much during work, communicating primarily through his craft and occasional written notes.

Most significantly, Ellaner discovered that William had never married, dedicating his life entirely to his work and the memory of his brother. Fellow craftsmen remembered him as solitary but respected, a man who seemed to carry a deep sadness, but channeled it into creating beauty. In 1945, as London celebrated the end of World War II, William had made a decision that would finally explain how the photograph had ended up locked away in Sarah’s drawer. Employment records from St.

Bartholomew showed that William had begun working on the home of a spinster named Sarah, doing restoration work on her Victorian terrace house. Church records indicated that Sarah had been particularly kind to William, perhaps recognizing in him a fellow solitary soul. She had commissioned him to create built-in cabinets for her home, work that required several months of careful craftsmanship.

It was during this time Eleanor realized that William must have entrusted the precious photograph to Sarah’s care. Perhaps sensing his own mortality and wanting to ensure this last link to his brother would be preserved. Ellaner’s research culminated when she discovered William’s death certificate from 1952. He had died at age 54 alone in his small workshop flat with no known relatives.

The local authorities had found his workspace filled with beautiful wooden objects but containing few personal possessions. However, the investigating officer had made a note that proved crucial to Eleanor’s understanding. Deceased kept detailed journal documenting his work and personal thoughts. Final entries mentioned entrusting important family photograph to dear friend Sarah for safekeeping.

Elellanar contacted the probate court and found Williams simple will written in his careful handwriting. The document was brief but heartbreaking. Having no family of my own, I leave my tools to the craft guild and my personal effects to my friend Sarah, who has shown me kindness in my final years. The photograph of my brother Thomas and myself should remain with her as she understands its value.

The final piece of the puzzle came when Ellaner met with Margaret Hartwell once more. Margaret revealed that her great aunt Sarah had indeed mentioned a sad, gentle man who had done beautiful work on her house and had become something of a friend in his final years. Aunt Sarah told me once that he had given her something precious to keep safe, Margaret recalled.

She said he had promised his brother he would always protect something important, and when he could no longer do so himself, he trusted her to continue that promise. Ellaner realized the photograph represented far more than a simple family portrait. It was a symbol of an unbreakable bond between two brothers, a promise kept across decades of hardship, separation, war, and loss.

Thomas had carried it through the trenches of World War I, and William had treasured it throughout his solitary life, ultimately entrusting its preservation to a kind woman who had honored that trust for 70 years. The strange appearance of William’s mouth, the facial condition that had brought him shame and difficulty throughout his life, had led to this remarkable story of love, sacrifice, and the enduring power of family bonds.

In death, the brothers were finally reunited through Elellaner’s research, their story preserved for future generations to understand and remember.