23rd April 1945. A small German town near Hanover. A broken barn stands at the edge of a field, its doors chained shut from the outside. Inside, 17 German women wait in the dark, thirsty, shaking. Told that when the American soldiers come, their real nightmare will begin. They have heard the stories.

Enemy troops taking what they want, the way German and Japanese soldiers did across Europe and Asia. Then it happens. Boots crunch on glass, chains rattle, and the doors swing wide. American uniforms fill the doorway, rifles in hand. The women press back against the walls, certain they know what comes next. But the soldiers do something no one in that town expected.

They lower their guns, offer water, call for medics, and walk away without touching a single woman. Why did leaders lock these women up as a gift? And why did the Americans refuse to take it?

23rd April 1945 near the town of Leair close to Hanover. The war in Europe had only weeks left, but for the men of the US 89th Infantry Division, the day felt like any other, cold, gray, and tense. Their division had about 15,000 soldiers on paper, but in this place, it came down to a small squad walking past a halfburned farmhouse and a leaning wooden barn. Sergeant William Matthews led the way.

His boots sank into wet mud. He could smell damp earth, old manure, and smoke from houses that had burned when the town fell 3 days earlier. Somewhere a door banged in the wind. Otherwise, it was very quiet. The barn doors were chained from the outside. That was strange. Barns in this part of Germany were almost always open, full of cows, tools, or refugees. Matthews raised his hand for the men behind him to stop.

Metal links clinkedked as he tested the chain. Then he nodded to a private with bolt cutters. The cut was sharp and loud. As the doors swung open, the stale air rolled out. It smelled of straw, sweat, and fear. A heavy, sour smell that had been trapped for too long. At first, Matthews’s eyes saw only darkness and shapes. Then the shapes moved.

17 women huddled in the corners, pressed against the rough wooden walls. Their dresses were dirty and torn, their hair matted, bare feet on cold, packed earth. Some looked no older than 16. The oldest had gray in her hair and the posture of a former school teacher. When the soldiers appeared in the doorway, the women did not cry out in welcome. They flinched.

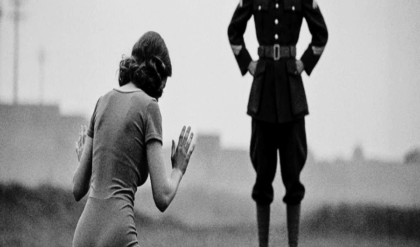

One young woman covered her face with both hands. Another began to shake so badly she could not stand. A girl who looked about 17 bit her knuckles to stop herself from sobbing out loud. Later, one of them, Anna Schmidt, would remember thinking, “This is the moment they have come to use us.” Matthews lowered his rifle.

He had seen dead men in ditches, villages flattened by shellfire, even a concentration camp with its rows of bodies. But this was different. These people were alive and waiting for something they clearly believed could not be stopped. Behind him, Private James O’ Connor muttered, “Jesus, Sarge, what is this?” His voice faded as he understood what he was looking at. An older woman pushed herself upright, leaning on the wall.

Her German was broken with fear, but Matthews caught enough, and she added a few words in clumsy English. “We are here for you,” she said. the burgermeister. He said you would want us. He say this will save the town. 2 days, no food, no water. We wait. The paradox hit hard. These women thought they had been locked up as a gift as payment to invading soldiers. Matthews later wrote to his wife.

They were sure we had come to rape them. Not because of anything we had done, but because of what their own leaders and our enemies had taught them to expect. He snapped back to the present. Oh, Connor, get Captain Henderson. The rest of you, put your weapons down, find water, rations. Now, his men hesitated only a second, thrown by the clash between what the women expected and what they themselves had been trained to do.

Within 20 minutes, Captain Robert Henderson arrived, coat damp from the mist. He was 32, but looked older, lines cut deep by months of combat and too little sleep. He stepped into the barn, took in the sight of 17 half-starved prisoners, and his jaw tightened. “How long have they been here?” he asked.

“About 2 days, sir,” said Corporal Thomas Riley, a medic who had just finished checking pulses and pupils. Dehydrated, malnourished. “Two are bad. They think we’re waiting to.” He could not finish. Henderson did not need him to. He knew the wider pattern. Division intelligence had already warned of at least four other towns where German officials had done something similar, locking up women as comforts for American troops, assuming the worst. He turned to his men, “Listen carefully.

These women are to be treated as civilians under our protection. Get more water, Krations, whatever we can spare.” A standard Kration held roughly 2,800 calories. Today, some of that precious food would go to former enemies. Riley arranged transport to the displaced person’s center in Hanover and passed this down the line. Anyone who lays a hand on these women faces a court marshal. No excuses.

In that dark barn, another contrast came into focus. Outside, artillery still rumbled in the distance. Across Europe, millions were still in chains. Yet at least a group of women prepared for abuse were instead given dry blankets, hard chocolate, and sips of clean water from dented metal cantens. One of the women whispered, hardly believing it. They bring us food. Why? We were told all soldiers do this.

Her words hung in the dusty air. But this was not propaganda. It was reality. The Americans had a choice. And in this forgotten farmyard they chose restraint over revenge. What the women did not yet know was how carefully their own town had chosen them for this fate and how many quiet meetings and whispered fears had led to their imprisonment in the first place.

2 days before the barn doors opened on the 21st April 1945, the leaders of the town of Leia met in a dim room above the rat house, the town hall. Outside, people could hear the distant thud of artillery and the low drone of engines as Allied columns moved closer. The war had lasted more than 5 and 1/2 years. Over 5 million German soldiers were dead or missing.

Now the front was at their doorstep. Inside the air was close and smoky. A weak light bulb swung slightly, making long, jumpy shadows across the wooden table. The Burgermeister, Wilhelm Krauss, wiped sweat from his upper lip. Around him sat the remaining members of the town council.

All men, most too old or too useful, to have been sent to the front. They had spent years hearing Nazi radio and reading Nazi papers. Those messages always said the same thing, that British and American soldiers were nagger troopen and criminals, that they would rape German women and burn German homes, that they were no better than bolevik beasts from the east.

Some of it was pure invention, but the stories about the Red Army in the east had a core of truth. In East Prussia and Cellesia, Soviet soldiers had raped thousands of women as they took revenge for what the Vermacht and SS had done in their country. Rumors had spread fast. By 1945, historians estimate that around 2 million German women were raped in the last months of the war, many of them by Soviet troops.

The actual numbers were confusing, but the fear was real. In lair, people whispered, “If this is what the Russians do, surely the Americans will do the same.” Krauss and his council did not trust official promises anymore. They believed one thing clearly. The strong do what they want in war, and the weak must offer something to survive.

One of them is supposed to have said, “Better a few sacrificed than all taken.” It was a cruel kind of math, but it was the logic they chose. So, they made lists. They told the town police chief to bring the records from the population office. It smelled of ink and old paper as he spread the cards and books on the table. Line by line, they went through the names of women in lair. First, they looked for those who were unmarried and without children.

Then, they added some young widows. They told themselves, “These women will not be missed as much. They do not have husbands here. They have no babies to feed.” Later, Fra Greta Hoffman, a school teacher in her 40s, told an American interpreter, “They said we had been chosen to save lair. They chose us like cattle. We were numbers, not neighbors. The police went out with their lists.

Boots echoed on stone streets. Doors slammed. At one house, they took Anna Schmidt, the baker’s daughter, only 18 years old. Her father tried to block the doorway. A rifle butt to the ribs knocked him aside. Her mother screamed and clung to her skirt until another blow sent her to the floor. They said I was unmarried with no children.

Anna later recalled, “They said that made me expendable. That word stayed in my head. Expendable.” At another address, they took Elizabeth Weber, a 25-year-old cler, from the town office. She knew the policeman by name. They had once joked with her about paperwork. Now they spoke stiffly, eyes hard. “You are on the list,” they said.

“Come.” The women were gathered in the dark, their shoes taken so they could not easily run. One bucket of water for 17 people, one shared corner for their needs, the rough boards of the barn pressed against their backs. Dust floated in the light from the cracks.

At night, they could hear the town beyond the walls, distant crying, hurried footsteps, the rumble of army trucks on the main road. Some tried to refuse. Two women made an attempt to slip away that first night. The police caught them, dragged them back, and beat them so badly that one could barely walk. They locked them in the cellar. Elizabeth said, “We heard them crying in the dark.

These were men we had known all our lives. They did this without a pause. The town leaders tried to cover their guilt with fine words. They told the captives that they were doing their duty, that by giving themselves to the Americans, they were protecting German motherhood and the future of the race.

It was a twisted use of the same language the Nazis had used for years, sacrifice, honor, blood. But the truth was simpler and uglier. The council had decided that these 17 women were a kind of payment. The paradox was sharp. They spoke of honor while treating their own people as objects to be handed over. Historian Anthony Beaver would later write that such scenes were not rare in 1945 Germany.

In town after town, fear and propaganda mixed into the same bitter drink, and local officials made choices that would haunt them. in lair. Those choices led directly to the chain doors and the stinking straw where the women waited. They waited for American soldiers to finish the crime their own leaders had begun.

What the council did not expect was that those same American officers would soon turn their careful lists and secret orders into evidence for a very different purpose. Not to use the women, but to judge the men who had offered them. The morning after the women were found, the barn stood open. Sunlight cut through the dust. A few empty kration boxes lay by the door, the sharp smell of canned meat still in the air.

Nearby, Captain Henderson sat at a rough wooden table, his wet overcoat hanging from a nail, a typewriter in front of him. The keys clicked as he spoke his report aloud for Sergeant Robert Hawkins to type. Division headquarters, 89th Infantry, he began. We have discovered a group of 17 German women held in a barn by order of local authorities. They were to be used as sexual offerings for American troops under the belief that we would commit mass rape similar to that perpetrated by German forces in occupied territories.

The words sounded cold, almost legal, but the anger behind them was clear. Hawkins, who had already filled several notebooks during the campaign, later wrote in his journal, “I wanted this down on paper so no one could ever say it was just a rumor or an excuse.” Henderson’s orders from the night before were turning into full action.

By 10:00 a.m., two olive drab trucks from division headquarters pulled up, engines rattling. Military police climbed down, white helmets bright against their dark uniforms. A civil affairs officer followed, carrying a folder thick with forms. The medics carefully helped the women into the trucks. Rough wool blankets scratched their skin, but at least they were warmer than the barn.

The metal floor of the truck was cold under their bare feet. One woman whispered, “Now it begins.” But another pointed to the red crosses on the medic’s armbands and said, “Maybe not.” Henderson spoke to the MPs in a voice everyone could hear. These women are under our protection. No one touches them. You will guard them until they reach the displaced person center in handover. Any violation will be punished. Court marshall prison.

This was one of dozens of such centers the allies were setting up. By mid 1945, there would be more than 2 million displaced persons under Allied care in Europe. Former prisoners, forced laborers, and civilians like these women moved by war from their homes. But while the trucks rolled away, leaving behind a faint smell of exhaust and dust, another piece of the story stayed in lair.

Henderson ordered, “Bring me Burgermeister Krauss.” The town leader arrived in the afternoon, escorted by two MPs. His face was pale and shiny with sweat. The small office they used for the questioning smelled of damp plaster, cigarette smoke, and wet wool from the solders’s coats. Rain tapped on the window.

Did you order those women locked in that barn? Henderson asked through Private Ernst Mueller, the German American interpreter. Krauss nodded quickly. Yes, yes, but you must understand. I did it to protect the town. We heard about what happens. We heard about the Russians. We thought if we gave you what you would take anyway, you would leave the rest of our women alone.

So, you imprisoned 17 women without food or water, Henderson said evenly, and offered them as what exactly? Krauss seemed almost surprised by the question. As comfort women, he replied. Like the Japanese have in Asia, like we had in Poland and Russia. It is how war works, is it not? The room went very still. Outside, a cart rattled over cobblestones. Inside, Matthews, standing against the wall, felt his fists curl.

He had seen American medics treat wounded German soldiers, watched GIS share chocolate with German children. And here was a man who thought they were no different from the armies that had filled Europe with rape camps. Henderson leaned forward. No, he said softly. That is not how we work.

You have committed a crime against those women. You expected us to finish that crime for you. We did not, and your expectation does not excuse you. He turned to his staff. We document everything. Statements from every woman who will talk, names of every official involved. Hawkins, you keep copies of all reports. Civil affairs will handle charges.

Later that year, on 10 July 1945, in a courtroom in Hanover that still smelled of fresh paint and old dust, Wilhelm Krauss stood before a US military tribunal. The judges wore American uniforms. The interpreter spoke calm German. Witness statements carefully taken back in April were read out. Krauss was found guilty of false imprisonment and conspiracy to facilitate sexual assault.

The sentence was 5 years in prison and a permanent ban on holding public office. His case became one of several hundred similar trials in the American occupation zone, most dealing with actual rapes or violent abuse. This case was unusual. It punished a crime planned in detail, but stopped by the very men it was meant to serve.

Sergeant Hawkins later wrote, “The true irony was this. They believed we were monsters because their own armies had behaved like monsters. When we refused the role, the only ones left to judge were the men who had trusted their own lies. The legal work in Hanover was only part of the story, however.

While papers were stamped and sentences read, the 17 women were learning day by day to live with a strange mix of relief, anger, and confusion in their new temporary home. What they felt and what they asked the Americans in those first weeks would expose a deeper wound than any courtroom could heal. The displaced person’s center in Hanover filled almost every room of an old school.

Classrooms that once smelled of chalk and ink now smelled of thin cabbage soup, disinfectant, and damp wool. In long halls, footsteps and voices echoed. There were German civilians, freed slave laborers from Poland and France, and survivors from nearby camps. In all, several thousand people moved through the building each day, part of the more than 2 million displaced persons under Allied care across Europe in 1945.

The 17 women from Lair were given two rooms on the second floor. Iron beds stood close together. Gray army blankets scratched their skin. Outside the windows they could see trams clanking past and people standing in line for food. It was a strange contrast. A place once made for learning, now holding people who had seen more than any book could tell.

Major Patricia Donnelly walked these halls with a clipboard under her arm. She was one of the few female officers in the theater, a former social worker from Chicago who had traded an office for army boots. She listened carefully, her shoes squeaking on the stone floors as she moved from bed to bed.

These women were abandoned in an organized way, she wrote in one report. first by their local leaders, then by neighbors who stayed silent, and finally by a system that taught them to expect rape as normal in war. She later told a colleague, “They have been dehumanized twice.

Once by being locked in that barn, and once by being told that this is what every army does. A few days after the women arrived, a new figure came through the door. Lieutenant Charles Morrison, an army chaplain. He was a Methodist minister from Georgia in his 30s with a tired but kind face. His canvas chaplain’s bag thumped lightly against his leg as he walked. The air in the stairwell was cool.

He could smell boiled potatoes from the kitchen below. Major Donnelly met him at the entrance to the women’s rooms. They are physically better, she said. We have given them food, clean water, medical checks, but their minds. She shook her head. They are still waiting for something bad to happen. It is like their fear is nowhere to go.

Morrison asked if he could talk with them in a quieter place. They chose the old school library. Dust lay thick on the high shelves. Sunlight shone through tall windows, making the air look golden. 10 of the 17 women agreed to come. They sat in a half circle of mismatched chairs. The smell of old paper mixed with the faint scent of soap from their first proper wash in days.

I am not here to preach at you, Morrison began through Private Ernst Mueller, who translated, “I am here to listen and to tell you that what was planned for you was wrong. Completely wrong. For a while nobody spoke. The ticking of a wall clock seemed very loud.” Then Anna Schmidt, the baker’s daughter, looked up. “Why did you not take us?” she asked.

Her German was simple. Müller’s English even simpler. We were told all soldiers do this. Our leaders said it is the way of war, but your men brought us water, food. They looked ashamed. Why? The question cuts straight to the heart of the paradox.

Women prepared for abuse, facing men who refused to abuse them, Morrison thought before answering. Some men in every army do terrible things. He said, “We are not perfect, but our commanders have clear rules. We punish rape. We punish theft. We teach our soldiers that civilians, even enemy civilians, are not targets.

” He paused, then added, “Many of our men have wives, mothers, sisters back home. They cannot imagine hurting someone else’s daughter and then looking their own daughters in the eye. That is not who we want to be. That is not who we try to be. Frag Greta Hoffman, the older school teacher, leaned forward. But you bombed our cities, she said sharply.

My cousin died in an air raid. Children died. How is that so very different? Morrison did not turn away from her anger. It is different. And it is also not different, he admitted. War itself is a moral disaster. People die who should not die. Bombing is meant rightly or wrongly to end the war faster, to destroy factories and rail lines. What was done to you had no such purpose.

Locking you in a barn to be used was pure exploitation. In another part of the building, Dr. Samuel Weiss, a psychiatrist from New York, was making his own notes. He spoke to each woman in turn, sometimes for an hour. The clatter of spoons in the dining hall downstairs drifted up through the floor.

“These women suffered what I would call anticipatory trauma,” he wrote in his report. “They were forced to expect sexual violence in detail. When it did not come, the relief was tangled with shame and disbelief.” One woman told him, “The Americans must want something later. No one helps for nothing.” She simply could not accept that kindness did not hide a trap.

Years later, Weiss’s report would be quoted in studies of trauma and war as scholars tried to understand how fear can wound even when the feared act never happens. In the library, as the talk with Morrison went on, that same clash between expectation and reality kept appearing. “We thought you were monsters,” Anna said quietly. “Instead, you were normal men.

But if you are normal, what does that make our own people? Who chose us for the barn? Her question hung in the dusty air. This was not propaganda. It was reality. The women and the Americans were both learning that day how deeply lies and violence had shaped their ideas of what was normal in war.

While doctors, chaplain, and social workers tried to heal minds and souls, others were working on something different, but just as important, making sure that what had happened in that barn would be remembered, and that Lair itself would not escape facing its shame. In the first months after Germany’s surrender, the country felt like a place half asleep.

Roads were crowded with carts and trucks. People stood in long lines for bread that often weighed less than 1 kilg per family. Many wanted only to forget, but the allies insisted that some things must not be forgotten. In the American zone, military courts opened in cities like Hanover, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg. Between 1945 and 1949, US authorities would hold several hundred trials for crimes against civilians and prisoners.

Some for mass murder, some for slave labor, and some, like the case from Lair, for sexual violence and the preparation for it. The trial of Burgermeister Wilhelm Krauss was only one small case in this larger effort. Yet for the people of Leair, it was a sharp mirror held up to their own faces. Sergeant Robert Hawkins sat in the back of the handover courtroom on the day sentence was read.

The room smelled of old wood, cigarette smoke, and damp coats. Rain tapped at the high windows. He held a folder on his lap thick with carbon copies of statements and his own neat notes. In his journal that night, he wrote, “They spoke of protecting their women.

The record shows they chose certain women to be harmed so that others might sleep easy. They called this honor. We called it what it was, a crime. The judges sentenced Krauss to 5 years in prison and barred him from public office forever. Some might have wished for more. Others thought even this was too harsh for a man who claimed he had only been afraid.

But the important thing was that someone in power had finally said out loud, “This was wrong.” Hawkins did not stop with the trial. Back in his quarters, he laid out photographs of the barn, maps of lair, typed translations of the women’s testimony, and copies of Henderson’s original report. The wooden table creaked under the weight of paper.

He filled notebook after notebook, more than 200 pages in all, the scratch of his pen mixing with the clink of mestins from the corridor outside. This was not propaganda, he wrote on one page. It was reality seen with our own eyes. History will remember our battles. I wanted also to remember what we did not do. After the war, Hawkins took all of this home with him to the United States.

Years later, he would donate his collection to what became the National World War II Museum in New Orleans so that students and scholars could read the words of Anna, Greta, Elizabeth, and others for themselves. Back in lair, life under American occupation slowly took shape. The sound of boots on cobblestones gave way bit by bit to the softer noise of bicycles and children’s voices. New food ration cards were printed.

A town that had once hung swastika flags now saw white and blue US military government signs nailed to its doors. Because Krauss could no longer serve, the Americans appointed a new burgermeister, Otto Fischer, a quiet man in his 50s, who had once spent time in a Nazi prison for political opposition. His office was a small room that smelled of old ink and coal dust from the stove.

One of his first acts was to call a public meeting. The town’s people gathered in the hall, their clothes patched, shoes worn thin. A few American officers stood along the walls. There was a murmur of voices, then silence as Fischer stepped to the front. His hands shook slightly as he unfolded a piece of paper.

“We must face what happened here,” he said, speaking slowly so everyone could hear. 17 women from this town were taken and locked in a barn. They were your daughters, your neighbors, your friends. Our former leaders chose them because they thought the Americans would do as our own soldiers had done in the east. He looked up, his eyes moving over the crowd.

Many of you knew. Some of you watched. Very few spoke in our fear. We abandoned these women. We treated them as something to be given away. We must say this clearly or we learn nothing. A murmur went through the room. Some people nodded, faces tight with shame. Others stared at the floor. Later, one woman who had been in the crowd told an interviewer, “We wanted to talk only about how we suffered.

He forced us to talk about what we did.” After the meeting, Private David Goldstein, the Jewish soldier from Brooklyn, who had once stood guard outside the barn, wrote to his mother, “The paper smelled faintly of army ink and the coffee he had spilled on the corner. I don’t know if what we did was heroic,” he wrote.

We just did what decent men should do. Maybe that is the real sadness. That ordinary decency now feels like some kind of miracle. If the world has fallen so low that not raping someone is a great act, then we have a long road ahead. The road ahead would be long for Lair, for Germany, and for the 17 women scattered now across camps and ruined streets.

But in the town hall’s stale air that day, with Fischer’s hard words still hanging, a first step was taken. The choice not to bury the truth. Decades later, when survivors and their families came back to that same town, they would stand before the old barn and see that those hard truths had been carved into metal for all to read. 50 years passed.

By 1995, the town of Lair looked very different. Cars hummed where horse carts had once rattled. New shops with bright windows lined the main street. Children rode bicycles past buildings that still showed faint scars of shellfire if you looked closely. The war was a story to them, not a memory. But on the edge of town, the old barn still stood.

Its wood was gray and rough from rain and sun. Weeds pushed up along the stone foundation. On a cool spring morning, a small crowd gathered there. Town officials, school children, a few American visitors, and several elderly women with careful steps and lined faces. Among them was Anna Schmidt, now Anna Mueller, 70 years old. Anna had left Germany long ago.

She had married an American soldier she met during the occupation and spent most of her life in Pennsylvania, teaching children who knew war, only from television and textbooks. Now she had flown back across the Atlantic, the steady hum of the jet replacing the roar of bombers that had once crossed the same sky.

The air around the barn smelled of damp earth and fresh cut grass. A light breeze moved the leaves of a nearby tree. In front of the door, a cloth covered a metal plaque fixed to the wood. The new mayor spoke first, his voice a little shaky through the small loudspeaker. We are here, he said, to remember something that many wanted to forget.

In April 1945, 17 women were locked inside this barn by our own authorities. They were meant to be used by American soldiers. Instead, those soldiers gave them food, water, and protection. Two school children stepped forward and pulled down the cloth. The metal plaque shone in the weak sun. Its words were simple.

In April 1945, 17 women were imprisoned here by German officials who expected American soldiers to assault them. The Americans did not. They brought food, water, and safety. Remember the evil that was planned and the good that was chosen. People shifted on the grass. Some wiped their eyes. A camera clicked. The contrast was clear.

A place once prepared for cruelty now marked as a warning and a lesson. A reporter turned to Anna. “How do you feel coming back here after 50 years?” he asked in German. She looked at the barn for a long time before answering. The wood, the roof line, even the smell of straw in the cracks pulled her back to that April day. “I feel many things,” she said finally.

“Fear, memory, anger, but also something like peace.” She took a slow breath. I do not tell this story to make Americans into saints, she went on. They were not perfect. They were just men doing their duty in a decent way. I also do not tell it to make Germans into monsters. We were a people poisoned by lies for 12 years.

Many were afraid, many did wrong. She put her hand on the rough boards. I tell it because even in the darkest time, people still have a choice. Our leaders chose to lock us in here. The American soldiers chose not to use us. That choice changed my life. Later, she added words that stayed with many who heard them. We could not believe no one touched us.

The Americans could not believe anyone thought they would. In that shared shock, maybe something began to heal on both sides. By the 1990s, historians had written many books about the end of the war. They compared armies, counted crimes, studied how often soldiers attacked civilians. Their numbers showed that while American troops did commit assaults and were sometimes punished for them, there was no plan of mass rape like the one carried out by some other armies. It was not automatic. It happened because officers enforced rules, because military police

investigated, and because enough soldiers believed that some acts were simply off limits. World War II had killed roughly 60 million people around the globe. In such a sea of suffering, the fate of 17 women in a single barn could seem very small. Yet, teachers in lair began bringing classes to the site each year.

At least a few hundred students came annually, touching the old wood, reading the plaque, and hearing the story. Their teachers told them, “This was not propaganda. It was reality. Your own town did this. Foreign soldiers refused it. Ask yourselves what you would do in their place.” In that way, the barn-in lair became more than a building.

It became a question posed to each new generation. The Americans had once come as conquerors, with tanks and guns rolling through the streets. Many years later, their veterans and children returned as guests, listening more than they spoke, reading German words carved in metal. In a quiet, human way they had come as conquerors and left as students.

From the rough boards of one barn, the view widened, to nations at war, to the power of lies, and to the fragile strength of ordinary decency in a brutal age. In the end, the story of the barn in Leair is not really about one town or one group of women or one American unit. It is about the thin line that separates freedom from tyranny and humanity from cruelty. a line drawn every day by private choices we almost never read about in history books.

The Nazi system tried to teach that power decides what is right. The refusal of those American soldiers and the later honesty of Leair’s new leaders quietly answered that power without conscience is only fear in uniform. In a war of tanks, bombs, and numbers, the most lasting force turned out to be something smaller and harder to measure.

The decision in a dark place to see an enemy as a human being and to act accordingly.