He wanted a bride who’d love the man, not the fortune. So he pretended to be blind. But when a saloon girl stepped off the stage coach in another woman’s place, what unfolded shocked even him. She didn’t come for gold. She came to heal. The stage coach rattled to a stop in the dry heat of Dusk Creek, its wheels crunching against gravel as the driver wiped his brow and called out, “Last stop.” A lone woman stepped down, her boots landing hard on the packed earth.

She wasn’t the kind most expected when they thought of May Lord her brides. No bonnet, no timid eyes, no polished locket tucked close to her chest. Instead, she wore a red dress faded from too many washings, a shaw wrapped loosely around her shoulders, and a grip on her satchel like she’d clawed her way out of someplace she never wanted to return.

Her name was Clara Win. She stood still for a moment on the edge of the dusty road, her gaze scanning the town, not with excitement or wonder, but a kind of restrained dread, like she knew the difference between a new beginning and just another bad chapter. Behind her, the stage coach groaned and pulled off. Ahead of her, Dusk Creek blinked sleepily under the sun.

No one came to greet her. She’d been told a man named Everett McAllister would be waiting with a cane, perhaps even a guide or a ranch hand, but the street was empty, save for a few curious onlookers loitering outside the general store and a dog with a limp. Clara squared her shoulders and walked forward anyway.

What she didn’t know, what no one knew, was that Everett stood at the corner of his own property, just up the hill, eyes sharp and seeing just fine. He watched through the haze rising off the land, arms crossed over his broad chest, his jaw tight as stone. He’d paid the postmaster to write the ad. He’d received dozens of replies.

He’d chosen a woman named Miss Annabel Cray, sweet, educated, even poetic in her letters. Clara Win wasn’t her, and yet here she was, alone. Everett turned to his foreman, a wiry man named Boon, who’d worked the McAllister ranch near 15 years. That her. Boon squinted toward town. Ain’t the one you picked. She don’t match the photo, but she sure came off that coach like she had every right.

Everett said nothing. He turned back toward the ranch house. Bring her up. Let’s see what a saloon girl thinks of pretending to be someone she ain’t. Boon hesitated. You sure you want to keep this blind act going? Might be simpler to just I said bring her, Everett interrupted. His voice was low but final.

The kind that didn’t beg questions. She came here expecting a blind man. That’s what she’ll get. Down in town, Clara found her way to the general store and asked for directions. The shopkeeper, a kindly older woman with a knitted brow, gave her a look that hovered between suspicion and pity. You Annabelle Cray. Clara hesitated, then nodded once. I see you’re expected up at McAllister Ranch.

Expected, Clara repeated quietly. The word didn’t sit right in her mouth. She hadn’t expected anything. Not really. She was just trying to outrun her past, and this was the last trail open to her. By late afternoon, Boon arrived with a buckboard and offered her a ride with no more than a grunt. She climbed aboard and held her satchel tight.

The land rising ahead of them like it had secrets buried in every dry hill. “You sure you’re ready for life up here?” Boon asked once, not unkindly. “I wouldn’t be here if I wasn’t,” Clara replied. It wasn’t arrogance, just exhaustion. At the top of the ridge, the house came into view, grand but weathered, its bones strong, even if its paint had long since faded.

Clara stepped down and found herself facing a man on the porch, seated in a rocking chair, a cane resting against his leg. His eyes were turned slightly away, unfocused. “Miss Cray,” he said. She stared for a long second. His voice was deeper than she’d imagined. Calm, measured, and utterly unreadable. “Yes, I’m Clara,” she answered before she could stop herself. Everett paused just a moment. “CL.” She bit her lip. Annabelle Clara Cray folks call me Clara.

Boon said nothing, but raised an eyebrow. Everett nodded slowly. “I’m Everett McAllister. I suppose we’ll both have to make adjustments. Inside the house was spare but tidy. Clara noticed everything. The worn marks where a man with sight might place his hands. The way the books on the shelf weren’t braille but ordinary prints.

The uneven dusting the tools placed just right. But she said nothing. “I hope the trip wasn’t too hard,” Everett said as she settled into the guest room. “I’ve known harder.” That night, as Everett sat by the fire pretending to read a book with fingers that never turned the page, Clara unpacked slowly. Her dress, her comb, a locket with no photo inside.

She stared at the mirror and wondered if she looked like someone worth lying to. Morning came with wind slicing through the valley. Clara rose early out of habit. She made coffee, fed the chickens without being asked. She didn’t speak much and Everett didn’t press.

She simply moved with quiet confidence, the kind that comes from someone who’s had to work for every single thing in her life. On the third day, Boon found her hanging clothes and asked, “You really Annabelle?” She paused. “No,” she said simply. He didn’t tell Everett. He didn’t need to. Everett already knew. Still, he said nothing. And Clara stayed.

Because sometimes the truth walks through the wrong door and still finds its place. But that same afternoon a telegram arrived sent from Cheyenne addressed to Everett McAllister. Annabelle Cray delayed stage coach missed will arrive in 2 days. Clara saw the envelope saw the name saw the lie she hadn’t told. And Everett sitting by the hearth with his blank eyes turned away whispered to the fire.

So, who are you really? Clara didn’t answer, but in two days time, she’d have to because the real bride was coming, and Dust Creek wasn’t big enough for two women with the same name. The fire crackled low that night, a soft rhythm like the ticking of a quiet clock, counting down to something inevitable. Clara sat alone at the small kitchen table, her hands wrapped around a chipped mug that had long gone cold.

The silence in the McAllister house wasn’t cruel, not like the saloon rooms back in Elhorn Ridge, or the long walk between camps, when no one dared speak for fear of who might hear. This silence felt measured, chosen, as if every unspoken word was a brick in a wall. Neither she nor Everett was ready to tear down. Upstairs, Everett moved slowly, as if pacing.

His cane tapped the floor at precise intervals, just believable enough for someone unfamiliar with the way blindness moved through a man’s body. But Clara had seen too many acts in her lifetime not to recognize one when it was performed. The only thing more calculated than Everett’s blindness was her own presence here. And yet neither of them had called the other out.

She stood eventually and moved to the sink, pouring the cold coffee out. The knock on the door came just as she set the mug down. Three knocks, slow, measured, not the kind a neighbor made. Not out here where neighbors were few and trouble wore boots. Everett didn’t react. Clara wiped her hands on her skirt, crossed the room, and opened the door.

Standing there in the moonlight was a boy no older than 16, freckled and raw boned with eyes too big for his face and a rifle slung across his back. He didn’t look scared, just determined. “You the new misses?” he asked, voice cracking slightly as if he hadn’t yet earned his full tone. “CL didn’t answer. She didn’t like the way he leaned his weight to one side or the way his fingers hovered near the strap of the rifle.

Everett in? The boy asked again. Behind her, Everett’s voice rang out calm and quiet. I’m here, Samuel. What is it? Clara stepped aside, eyes narrowed slightly. The boy entered and tipped his hat, not out of politeness, but because something about Everett still made boys like him straighten their spines. It’s your cousin Jeb, the boy said. He’s back. Everett’s jaw tensed.

Clara watched closely. He’s been asking round town. Told the bartender he’s riding up this way tomorrow. And why would Jeb think he’s welcome? Everett asked, his voice nearly void of emotion. The boy shifted. Word is he thinks your eyes don’t work anymore. thinks that means your hands ain’t good for Holden the deed.

Clara didn’t understand all the pieces. Not yet. But she understood the tone, the warning wrapped in that visit. I appreciate the ride up, Everett said finally. Get on home now, Sam, and tell your paw I’ll handle it. The boy nodded, glanced at Clara one more time, then slipped into the night without another word.

When the door shut, the silence returned, but now it pulsed with something taut, like the air before a storm. Cousin Clara asked. Everett turned toward the fireplace, his hand resting on the mantle like he needed the wood to hold him upright. Jeb McAllister, he thinks he’s entitled to what ain’t his. Always has. And he knows that I’m blind.

Everett’s voice was bitter. Now he’s counting on it. Clara crossed her arms, stepping slowly forward. Then maybe it’s time you told him you’re not. Everett didn’t flinch. He didn’t even look her way. And maybe it’s time you told me who you really are. The words hit like a slap, not in their cruelty, but in their precision. Clara held his gaze.

You already know I’m not Annabelle. I know what you’re not, Everett said. That’s not the same as knowing what you are. They stood in that silence for a long moment. Then Everett turned, walking past her toward the back door. “Jebb rides in tomorrow. You’re free to leave before then. I won’t stop you.” “I didn’t come to run,” Clara said quietly.

“No,” Everett murmured without looking back. “But you didn’t come for me either.” The door shut behind him. Dawn didn’t rise so much as it peeled itself from the horizon, bruised and gray and reluctant. Clara had barely slept. The creaking stairs, the weight of lies pressing against thin walls, the constant questions circling her thoughts.

Why did she stay? She found herself walking toward the barn, a thin wool shawl draped over her shoulders. The animals stirred as she entered, and Everett’s voice floated from the far stall. Careful, Daisy kicks if she don’t know you. Clara stepped closer, her boots crunching straw. You always up this early. Ranch don’t wait for secrets to sort themselves out, he said.

She hesitated. Why fake blindness? Everett leaned on the wooden beam, his eyes fixed somewhere near her shoulder. You ever been handed a love letter that made you feel like maybe, just maybe, someone out there might want you, not what you’ve built? Clara said nothing. Everett continued.

Then you find out they only answered the ad because the McAllister name is worth more than gold up here. So you lied. I tested. Everett corrected softly. There’s a difference. And what if Annabelle had stepped off that coach and passed your little test? Then I’d have married her, I suppose, and wondered every day if her kindness was because she loved me or pied me. Clara stared at him for a long moment. You think pretending to be helpless is a way to find out who loves you.

I think the world’s full of people who will love a man’s power, but not the man. A blind man’s got no power. not out here. Clara looked away. Neither does a woman who’s got no name left to stand on. He turned at that, something shifting in his face. What happened to you? She didn’t answer, not directly, just said enough to make me take someone else’s seat on a stage coach. They didn’t speak after that.

The quiet stretched between them. Not tense now, but careful. But by midday, tension returned like thunder on a clear day. Boon rode up fast, hat low, eyes sharper than usual. They’re common, Jeb and two men. He ain’t riding like family. Everett straightened from the porch chair. His fingers brushed the cane beside him, but didn’t pick it up.

Clara stepped onto the porch beside him. You going to keep the act up when he’s here? Everett didn’t reply. The three riders appeared from the ridge an hour later, dust kicking around them like they meant to cloud everything they touched. The lead man was tall, rough around the edges, with a grin that didn’t reach his eyes.

He rode like the world owed him a smoother trail, and he meant to take it one hoof printintrint at a time. He dismounted, stepping close to the porch with the familiarity of someone who thought his presence was a gift. cousin, he drawled. Jeb Everett replied evenly. You look good for a man who don’t see. Everett leaned slightly, one hand gripping the cane. Maybe I don’t need to see to no trouble when it rides up my road. Jeb laughed, but the sound was dry.

Heard you took on a bride. May lord her no less she the one. His eyes cut to Clara and something slick passed across his expression like he could see through her and still find use for what he saw. Clara didn’t flinch. I am, she said simply. Jeb’s mouth twisted. Well, isn’t that sweet. He turned back to Everett. I came to talk about the land.

Word in town says you ain’t got the legs or the eyes to run this place anymore. That true. Everett smiled slightly. Funny, the land seems to think I’m doing just fine. Jeb’s face hardened. You sure you want to do this the hard way? Everett’s voice dropped. You’d be surprised what a blind man can do when the stakes are high.

Something electric passed between them. A dare, a warning, a wound reopened. Clara stepped between them, not because she was brave, but because she knew this dance too well. This ain’t about land, she said. It’s about pride. Jeb’s eyes narrowed. And who are you to say what it’s about? I’m the one you didn’t expect, she said. And the one you won’t forget. The moment stretched.

Then Jeb spat in the dirt, mounted his horse, and said, “This ain’t over.” He turned and rode off with his men, dust trailing like a snake behind them. Everett exhaled slowly, eyes turned toward the horizon. Clara stood beside him, heart pounding. Neither said it, but something had changed. The test wasn’t just hers anymore.

Now they were both being measured, and the reckoning hadn’t even begun. The storm didn’t come all at once. It rose like bad blood, slow, hot, and inevitable. By the following morning, Jeb’s visit was already pulsing through dust creek like poison through a vein. Word spread fast in small towns, and by the time Clara walked into the general store for salt and lamp oil, the hush that followed her steps said more than anyone dared speak aloud. She’s the saloon girl.

Wasn’t even the real bride. I heard Jeb McAllister’s gunning for the ranch. They say Everett can’t even see straight. Clara heard all of it, pretended not to. She paid the shopkeeper, kept her chin level, and left with her basket like it didn’t sting. But by the time she reached the trail leading back toward the Mcallister Ranch, the salt felt heavier than it ought to in her arms, heavier than truth, heavier than regret.

Boon met her halfway up the path, wiping sweat from his brow with one sleeve, his hat pulled low. “He’s stirring things up,” he said without preamble. Jeb es in town all morning talking to the assessor’s office trying to argue Everett ain’t fit to manage the land and he thinks if he proves that he’ll take the deed Clara asked.

Boon gave a half shrug. Laws got loopholes. Families got claws. She looked toward the hills where the house stood solid as ever against the pale sky. Everett could shut this down with a word. Just say he ain’t blind. Boon studied her a long moment. A man who builds his life on solitude learns how to armor himself. This blindness. It’s more than a lie. It’s a shield.

If he lays it down now, he’ll have to show folks all the wounds underneath. Clara swallowed hard. And if he doesn’t, Jeb might take everything. Boon nodded once. That night, Everett didn’t come down for supper. Clara set a plate anyway and left it by the door. She didn’t knock. She didn’t press.

But as she turned to leave, she paused, fingers resting on the wood. “Tomorrow, I’ll ride into town,” she said through the door. “They’ll see me, hear me, let M say what they want. I’m not hiding.” She didn’t expect an answer. She didn’t get one. But the next morning, Everett’s plate was empty. The saloon hadn’t changed since Clara left it 6 months earlier.

Same broken rail, same busted chandelier that leaned sideways over the bar like a drunk with no good stories left. She stepped inside with her boots clicking soft against the warped floorboards, heads turned. Some looked away. Others didn’t bother hiding their recognition. “Clara win,” said a voice behind the bar, low and careful.

“It belonged to Josie, the saloon’s cook and closest thing Clara had to a friend before she disappeared. I thought you were dead or worse, married to some outlaw with a grudge. Almost, Clara said, voice thin. Josie eyed her from behind the whiskey bottles. You back for good. Clara shook her head. I’m not back at all, just passing through. Sort of.

Josie poured a glass of water, slid it across. Folks, say you’re living up at the Mcallister Place. I am. Josie’s brows rose with Everett McAllister thought he was half blind and all stone. “More like half- lives in all walls,” Clara replied. Josie leaned closer. “You sure you know what you’re doing?” “No,” Clara said, honest and blunt.

“But I know who I’m not, and I’m done running from her.” That afternoon, as the sun dipped lower in the sky, and heat shimmerred off the rooftops, Jeb McAllister returned. This time he wasn’t alone. He brought papers, witnesses, a clerk from the county office. And just before sunset, he stepped onto Everett’s porch like a man who’d already won.

“I’ve come to settle things,” he said. “Clean, legal. You hand over authority for the land, just until the court decides if you’re capable, and I’ll ensure the livestock doesn’t rot in the fields while you pretend not to see.” Everett sat quiet. came across his knees, his jaw working slow and hard. Clara stood beside him, arms crossed tight.

“You came with documents, but you didn’t come with proof.” “I don’t need proof,” Jeb replied smoothly. “Just concern, and concern s enough to start the process.” Boon leaned on the porch rail, watching silently. Jeb’s men spread out like snakes uncoiling. The clerk from the county adjusted his collar and coughed. “I’ve got no children,” Everett said finally.

“No heirs, so of course you’d want the land. But tell me something, Jeb. You think blindness makes a man foolish.” “I think it makes him vulnerable,” Jeb snapped. “Everse then, slow deliberate.” And he didn’t reach for the cane. He walked past it, down the porch steps, straight to Jeb.

“You want the truth?” he asked. “Here it is.” And then he looked him dead in the eye. Jeb froze. The others did, too. The clerk’s jaw dropped. “I see just fine,” Everett said. “And what I see is a coward. A man who didn’t earn anything, so he wants to steal what another man bled to build.” Jeb’s face twisted.

You lied to this town, to your own people. And you came to rob your own kin, Everett replied. Jeb reached for his pistol. Reflex panic. But Boon was faster. His rifle cocked before the leather cleared Jeb’s holster. Don’t, Boon said softly. Not here, not now. Jeb hesitated. Then dropped the weapon. The clerk took a step back. This land’s mine, Everett continued.

This ranch, this house, the work in it, and anyone who wants to take it better come with more than paper and poison words. Clara stepped down beside him, her voice firm, and next time maybe bring the real bride. That part hit hard. Jeb looked from Clara to Everett, then back again. The meaning settled in the insult, too. He spat into the dust. This ain’t the end. No, Everett said, voice low.

It’s the beginning. Jeb and his men rode off, their silhouettes long and angry against the dying sun. The clerk didn’t stay behind. By the time the horizon swallowed their dust, the porch felt quiet again, but the quiet didn’t feel fragile. It felt earned. That night, Clara stood by the window in the main room, watching the moon rise.

Everett poured a second glass of whiskey and handed it to her without speaking. She accepted it, fingers brushing his for just a second longer than needed. “I never meant to lie,” she said. “Not like this. I just needed somewhere to land.” “And I gave you a landing place built on lies of my own,” he answered. “They sat together, the fire casting their shadows against the walls.

” I don’t care about the land, she said softly. I care that you stood up when it counted. Everett looked at her then truly looked. And I care that you stayed, he said. She smiled. A real one, tired, but real. I’m not going anywhere, she said. But the next morning, everything changed again. A new telegram arrived. This one addressed not to Everett but to Clara. And it read, “Anabel Cray has arrived.

Demands to know why another woman answered her ad. She’s headed to McAllister Ranch today.” Clara’s breath caught. Everett read her expression. “What is it?” She handed him the telegram. He read it once, then again. Looks like the real test is just beginning,” Clara whispered. Everett’s voice was quiet, and this time we take it together.

But neither of them knew what Annabelle would bring with her, or who she’d bring with her, or what truth she might reveal. The sun barely crested the ridge when Boon spotted the rider. One woman, one horse, dust kicking up behind her in an even rhythm. No guard, no escort, just a hard, fast ride with a purpose.

He didn’t need to say it aloud. Clara was already at the window, eyes locked on the trail. She hadn’t dressed yet, her hair still half twisted, apron folded over the back of the chair. The telegram lay open on the table between her and Everett, its words curling like smoke in the heat of the room.

Everett leaned forward in his chair, elbows on knees. He looked at Clara, not with accusation, not even curiosity, but with something deeper, a quiet patience that felt heavier than any judgment. “She’s early,” Clara said finally. “Or maybe we’ve been late,” Everett replied. The sound of hooves drew closer.

Clara stepped back from the window. “What do we say?” Everett stood slowly, smoothing the creases in his shirt. “We say what needs saying.” There was no time to talk it through, no time to choreograph the dance. The woman was already tying off her res at the post outside the porch, one boot hitting the ground like punctuation.

She looked exactly like her photograph, sharp cheekbones, pale blue eyes, the kind of posture that came from years of refinement or rigid upbringing. She wore a traveling coat too fine for dust creek and gloves that had seen little labor. She knocked twice. Not timid, not rude, just precise. Everett opened the door himself. “Miss Cray,” he said, voice level.

The woman blinked, taking him in. “You’re not blind.” He nodded. “No.” She turned her gaze toward Clara, who’d stepped beside him in silence. “I see,” Annabelle said. “You came a long way,” Everett offered stepping aside. Annabelle didn’t move. And yet someone else answered in my place. You lied about your condition and she stole my name.

Tell me why I shouldn’t ride back and send word to every paper in the territory. Clara stepped forward because I didn’t steal anything. Annabelle looked her up and down. No, you wore my name. I borrowed it. I never intended. But you stayed. Annabelle cut in. Clara’s voice didn’t falter. I stayed because I found something here worth staying for. Everett looked at her, but she didn’t glance back.

Her words were hers alone. Annabelle stepped into the house without invitation. Her gloves clicked softly as she removed them. “Let’s not pretend this is a love story.” “We’re not pretending anything anymore,” Everett replied. They gathered around the table. Boon lingered near the door. tension taught in his jaw. Annabelle spoke first.

I wrote letters, honest ones. I said who I was, what I could offer. I never once lied. No, Clara said, “But you also never got on that stage, coach.” Annabelle’s brow lifted. Because my father fell ill, I stayed to nurse him. Clara tilted her head. And yet, here you are now, less than a week later. Annabelle’s nostrils flared. He died. The silence stretched. Boon cleared his throat and stepped outside.

Everett let the moment settle. “I’m sorry for your loss,” he said quietly. Annabelle nodded once. “Thank you.” “I don’t blame you for being angry,” he continued. “But I need you to understand what happened here. It wasn’t planned.” Clara didn’t scheme her way into my life.

She arrived the day the stage pulled in, and when no one else got off, I assumed wrongly that she was you, and by the time the truth came, she’d already saved this place more ways than I can count.” Annabelle folded her gloves. “That doesn’t make it right.” “No,” Clara agreed. “But maybe it makes it worth something.” Annabelle’s eyes narrowed. “Do you love her?” Everett didn’t answer immediately. He looked at Clara truly looked and then back at Annabelle.

I don’t know what name she carries, he said, but I know the strength in her hands, the steadiness in her voice, and the way she stood by me when a man came to steal my land and dignity. If that’s not love, it’s close enough that I’ll keep fighting to find the rest. Annabelle stood abruptly.

Then I suppose I came here for nothing. You came for truth, Clara said. And now you have it. Annabelle stared a moment longer, then exhaled. Do you have any idea what people will say about this? A rancher faking blindness? A saloon girl parading as a bride. They’ll say what they want, Everett replied. And we’ll live with it. Annabelle gave a tight nod.

You’ll need to explain things to the postmaster and to judge Thorne if he hears word. I will. She gathered her things without another word. As she reached the door, she paused. “To be clear,” she said without turning around, “I don’t envy you. I don’t pity you, but I do hope for your sake that this ends well.” Then she was gone.

The next week passed like a test neither of them had studied for. Word spread fast. First the truth about Everett’s vision, then Clara’s past, then whispers that Jeb might return with lawyers or worse. But Dusk Creek, for all its gossips and glare, didn’t turn them out. The general store clerk began nodding again.

Josie sent a pie wrapped in flannel cloth with no note. Even Boon, though gruff as ever, didn’t hold back his usual snorts when Clara teased Everett over supper. Still, the days didn’t come easy. Clara worked hard. She patched the roof alongside Boon.

She scrubbed the floors until the pine shone again, and she cooked with whatever little they had. Not because Everett asked, but because building something felt better than waiting for it to crumble. One evening, after a particularly long day mending fence wire, Everett sat beside her on the porch. The sky bled pink across the ridge. “You could leave,” he said quietly.

“Still time, still space between what we are and what we haven’t said. She didn’t look at him. Just watch the last hawk ride the wind. I could, she said, but I won’t. He nodded once, and that was enough for now. But now didn’t last. Boon returned late the following night, his face pale under the moonlight. There’s men camped near Widow’s Ridge, he said breathless.

Jeb’s riders, five or six of them. Everett stood armed. Boon nodded. He ain’t coming with paper this time. Clara’s voice was low. What does he want now? Boon’s eyes flicked toward Everett. He wants blood, and if not that, then fear. That night, Clara sat alone by the fire long after the others turned in. Her hands shook slightly as she fed a new log to the flames, not from cold, but from memory.

She’d seen what men like Jeb could do when the law didn’t bind them. She’d watched towns fold under threats, watched women disappear with no one asking where. She thought of the saloon, the coins dropped on tables like chains. The days she thought escape was a myth told by girls too green to know better.

And now she had something worth defending, someone worth believing in. When Everett stepped out of his room, she didn’t pretend to be asleep. “I won’t let him take it,” she said before he spoke. “Not the land, not you.” He walked over slowly, sat across from her. The fire light cast shadows in the hollow of his cheeks. “Then we fight,” he said.

“Together.” His voice didn’t shake. Always. Jeb McAllister didn’t ride in with fire. He came like a cancer, quiet, suffocating, inevitable. By the second day, reports reached town that fences had been cut, water barrels drained, calves gone missing. Someone poisoned the well near the south pasture. Boon chased shadows day and night.

Everett slept with his rifle nearby. Clara kept the kitchen lit longer than usual, just in case someone tried to approach under cover of night. On the third day, a letter arrived. Nailed to the front gate. You’ve made your point, cousin. Now I’ll make mine. Leave the land or bury yourself in it. One week.

No signature. No spelling errors either. Everett read it twice, then fed it to the fire. I’ll go to Judge Thorne, he told Boon. And what will you say? Boon asked. that your cousin threatened you with shadows and drought. You think Thorne don’t know how land works out here. It belongs to the one strong enough to hold it.

Clara didn’t speak for a long time. Then she said, “Then we give him nothing. No weakness, no ground, no story to twist.” Everett looked at her and for the first time there was no barrier between them, no test, no act, no lies, only resolve. Clara leaned forward, fire light in her eyes. If he wants war, he’ll have to come take it.

And in the distance from behind the hills, a wolf howled, a warning or a promise. The fifth day started with silence. Not the peaceful kind, but the kind that made you listen harder. No bird song, no rustle of cattle. Even the wind seemed to hold its breath. Clara stood at the edge of the porch, coffee gone cold in her hands, watching the tree line like it might breathe. Boon hadn’t returned from the ridge.

He’d gone out before dawn, just after a pair of dogs began howling near the creek. Everett had tried to follow, but Boon waved him off. Said he needed to move quick and the boss should stay where he was. That was hours ago. Now the sun was high and nothing had moved on the land except the clouds. Clara gripped her shawl tighter, her mind playing with memories she didn’t want.

Her old life had taught her what waiting meant, how it clawed at your nerves and planted fear like seeds that bloomed too fast. She stepped off the porch and walked toward the barn. Moving helped, work helped. Anything to keep her hands busy. She didn’t hear the horse at first. Only when the barn shadow deepened behind her did she feel it, that shift in the air, that faint sound of hooves crunching into dry grass. She turned slowly.

Boon’s geling limped toward the house, rains dragging in the dirt. But Boon wasn’t in the saddle. Clara dropped the pitchfork and ran. The horse bore a fresh cut across its flank. The saddle was loose, turned halfway. One of Boon’s boots was still caught in the steerup. Everett stepped onto the porch just as she reached the animal. His face drained of color.

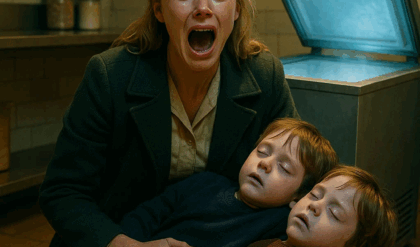

“Get the gun,” he said. “She didn’t argue.” They found Boon an hour later near Widow’s Ridge. He was alive, but barely. Dragged half a mile through the brush, his shirt torn, face bloodied, one arm bent at the wrong angle. Jeb hadn’t finished him. That wasn’t the point. The message was clear.

We can reach you and we’ll choose when to finish what we start. They brought Boon back, wrapped in a blanket, Everett holding the res while Clara pressed cloth against the worst of the wounds. Boon drifted in and out of consciousness, muttering phrases that didn’t make sense.

Two of M, maybe three, never saw the third laugh like a coyote. Boots smelled like tar. They waited. They knew I’d ride alone. Clara tended him until her hands achd. She boiled water, crushed herbs Josie had left behind weeks ago, and cleaned the gash on his thigh with trembling fingers. She didn’t flinch at the smell of blood, didn’t cry when Boon screamed through his fever.

She just kept going because she knew what it meant when fear had a face. And Boon wasn’t the last face they’d aim for. That night, Everett stood watch. Clara sat at Boon’s side, dabbing sweat from his forehead. “You ever had someone come for you before?” he asked, voice low. “Plenty,” she replied. “But never because I mattered.” “You matter now,” she looked up at him.

The fire cracked once between them. “I hope that’s enough.” The next two days passed with slow dread. Boon didn’t wake fully. Clara took over his chores without asking. Everett patrolled the land with a rifle strapped to his back. Neither of them spoke much, but every now and then Everett would glance across the room like he was trying to say something he couldn’t name. And then came the fire.

It started just after midnight, a glow in the west pasture, low and angry. By the time Everett smelled the smoke, it was already chewing through the dry grass like hunger. He and Claraara ran. Buckets, blankets, dirt, anything to kill the flames, but it spread fast, too fast. By dawn, the fence line was gone. Three calves, too.

Boon woke during the chaos, delirious, asking about the fire. Clara soothed him, then ran back to help Everett. They fought side by side, ash in their lungs, heat blistering their skin. Everett’s voice went horsearo from shouting. Clara’s skirt burned along the hem, but she didn’t stop until the last ember died. And in the smoke, just as they collapsed to their knees, she saw it.

A single bootprint pointing toward the barn. Jeb hadn’t lit the fire to destroy the land. He’d done it to draw them away. The barn was half looted, rope, tools, the better saddle gone. But that wasn’t the worst of it. The horses were dead. Both necks snapped. Not stolen. Not written off. Killed. Message sent. Everett stood over them in silence.

His fists clenched, his breath shallow. Clara touched his arm, but he didn’t move. We should leave, she whispered. Just for now, until we can bring a marshall. He didn’t look at her, just stared at the straw soaked in blood. No, he said finally. If we leave, we lose everything.

If we stay, we might lose more than land. He turned to her then. And if we let men like Jeb think they can win this way, who will stop the next one and the one after that? She didn’t argue. She couldn’t because he was right. But fear curled in her stomach like a trapped bird. The next day, Everett left.

He didn’t say where, just that he needed to ride out alone, that he’d be back by dusk. Clara watched him go with her chest tight. Boon woke that afternoon with clearer eyes. She told him about the fire, the theft, the horses. He didn’t say much, just reached for his rifle and winced when his ribs reminded him of their condition. “Everit’s gone to the judge,” Boon guessed. Clara nodded. He didn’t say. He don’t have to.

Boon looked out the window, jaw clenched. You scared? She didn’t lie. Yes. Good. Boon said, “Means you know what’s worth protecting.” Evening fell too slow. Clara checked the window every few minutes, watching the horizon like it might answer back. When Everett finally returned, his coat was torn, his knuckles split, his horse was missing.

He walked up the porch alone, covered in dust and sweat, and leaned against the doorframe like the last wall just fell. Clara met him with a rag in a basin, hands trembling. What happened? He took the cloth, pressed it to his brow. I made it to Thorne. And he can’t act without proof. Claims are claims. Without witnesses or a confession, he won’t intervene.

Clara sat down hard, but Everett added. He said if we’re attacked again, he’ll ride up himself. She looked at his bruises. You were followed. He nodded once. Two men. I took care of them. Not forever, but enough to make M crawl back. She reached for his hand. Held it. I don’t want to lose this, she whispered. You won’t. He meant it.

But outside in the dark beyond the lanterns glow, someone watched. Not from the trees. Closer. Behind the shed, Jeb. Grinning, waiting. Jeb moved like a man with time on his side. He didn’t rush. He didn’t shout. He didn’t need to. The kind of destruction he dealt in was slow, like rot beneath a floorboard.

Quiet, hidden, patient. And now, in the deep hush between midnight and dawn, he crouched behind the McAllister shed, close enough to hear the murmur of Everett’s voice through the window. “They’re not going to stop,” Everett said inside, his words half muted by glass. “Not until we bleed or break.” “I know,” Clara replied.

“But if we hold out one more day, Thorne will come.” Boon said he would. “He’s right,” Everett said. But one day’s a lifetime if the devil walks it. Jeb smiled at that sour and wide. He slipped back into the trees like a shadow pulling its own leash. He had one night left to finish what he started.

One night to make Everett pay for every slight, real or imagined. Dawn came with a sharp chill and a strange stillness. No birds, no wind, just a kind of pressure like the land was holding its breath again. Clara stepped outside with a kettle in hand, her eyes scanning the ridge without knowing why. Inside, Boon tried to sit up for the first time in days.

“You look like death,” Clara told him as she helped him straighten. “Feels worse,” he muttered. “But I ain’t letting that bastard win without seeing my face one more time.” She smiled, but it didn’t reach her eyes. I’ll boil water for the bandages, but she never reached the stove. The gunshot cracked like lightning. One, then another.

Everett burst through the front door with his rifle in hand. Boon tried to rise, but gasped halfway, slumping against the wall. Clara rushed to the window. Smoke curled from the direction of the east pasture. “They’re here,” Everett said, voice flat. Clara turned toward the door, already moving. No, he barked.

I’m not hiding, she snapped. Then stay behind me. They reached the pasture just as the third barn wall gave into flame. The sky glowed red and smoke clawed at the sun. Three riders circled near the trees, dark figures on darker horses. Everett aimed carefully and fired once. One of the men jerked back, clutching his side, and veered off. The others scattered.

Jeb wasn’t among them. Clara ran toward the troughs, hauling a pale of water. Everett joined her, smothering sparks at the fence line. They worked in grim rhythm until the fire hissed and died. Then from the trees, another shot. This one tore through the air and punched into the ground inches from Claraara’s feet. She froze.

Everett stepped in front of her, rifle raised, searching the trees. Silence, then a voice. You always were a good shot, cousin. Jeb emerged slowly, his coat hanging loose, his revolver drawn, but lowered. You think you win this by playing defender. You think love and guts and a burned down barn make you a landowner. Everett didn’t blink.

I think I earned this land with blood, with years, with every god-forsaken winter that nearly buried me in it. And you think some from Elhorn Ridge gets to stand on it like she belongs? Jeb snarled. Clara didn’t flinch. She stepped beside Everett. I’m not from Elhorn anymore. You’ll always be what you were, Jeb spat. Everett raised his rifle.

And you’ll always be nothing but what you try to take. Jeb’s revolver lifted fast. Too fast. A shot cracked, then another, but not from Everett. From the porch boon. Pale shaking, leaning against the post for balance. But his aim was true. Jeb screamed as the bullet tore through his shoulder. He stumbled back, dropped his gun, and fell to his knees.

Clara rushed forward, kicked the weapon away. Everett moved slower, steadier. He loomed over Jeb like a shadow the land itself had cast. “You come back again,” he said coldly. “And I won’t be the one talking.” Jeb didn’t answer. His breath came in short, pained gasps.

Clara crouched, yanked a length of rope from the trough post, and tied his wrists without waiting for permission. She looked up at Everett. What now? He exhaled. We send word to Thorne. Let the judge handle the rest. Boon limped down the steps. I’ll ride. You sure? Everett asked. Boon smiled grimly. I want to be the one who tells him we held. Judge Thorne arrived by midday with two deputies and a wagon.

He said little, just listened, asked questions, took one look at the bullet hole in Jeb’s shoulder, and nodded. “He’ll hang,” Thorne said, not for trying to steal land, but for spilling blood on it. The deputies hauled Jeb away. No one watched him go. “Not even Clara.” The ranch was quiet again that evening. Ash clung to the wind.

Clara stood near the fence line, watching the sun bleed over the hills. Her hair was messy. Her hands blistered, but her spine was straight. Everett joined her slow, steady. He’ll be back, she said. No, Everett replied. Not this time. She glanced sideways. Then it’s over. He looked at her. It is. She nodded, then stepped closer.

I lied when I got off that stage, coach,” she said softly. “I lied because I didn’t know if I could survive without lying. I’d spent so long pretending to be someone else that stepping into Annabelle’s name didn’t feel wrong. It felt like armor.” “And now,” he asked, “I don’t need armor here.” He reached out, took her hand, then stopped wearing it.

She closed her eyes and when she opened them again, she was no longer Claraara the runaway, no longer Claraara the saloon girl. She was just Clara Win. And this was her home. But the West doesn’t keep quiet long. Two days later, a letter arrived. Not from a marshall, not from a court. From Annabel Cray. I’ve changed my mind. It read. Dusk Creek is not done with me.

I will be returning to claim what was promised. If not the man, then the land. Consider this notice. Clara read it twice, then handed it to Everett. He read it once, then burned it. She watched the ash scatter on the wind. But in the corner of her heart, she knew peace was never permanent, especially when it was built on stolen names and broken promises.

The wind carried the scent of rain before the clouds ever darkened. Clara stood on the porch with her arms crossed, the horizon painted in moody streaks of gray. That letter hadn’t left her mind since it burned, its words seared deeper than the paper it was written on. If not the man, then the land.

She knew what Annabelle meant by that, and she knew that the judge might not be able to protect them from the lawless kind of revenge that moved in silence, dressed in silk gloves and tied off corsets. Three days passed without a sign. No writers, no letters, just silence. But it wasn’t the good kind, not the quiet of a home at peace.

This one hummed with the promise of change, like a storm building its weight before the downpour. Boon was up and moving again, though slow and favoring his left leg. He worked the outer fields during the day, checking fence lines and smoking quiet while he watched the road.

Everett focused on repairs, barn door hinges, scorched fence posts, soot black beams that needed replacing. Clara joined him every step of the way, her hands blistered, but sure. They didn’t talk much, not because there wasn’t anything to say, but because the things that mattered were already known between them.

But on the fourth morning, the sound of a carriage reached them just past sunrise, polished wheels on gravel, followed by the unmistakable click of hooves, and a high-pitched voice barking commands at a driver. Clara froze by the trough. Everett looked up from the shed. Boon squinted from the field. The McAllisters had a visitor. The carriage was unlike anything Dusk Creek had seen in years.

Glossy black with silver trim, pulled by two sleek mayes that looked borrowed from a judge’s parade. The driver, stiff and expressionless, wore city-tailored clothes that didn’t belong in this part of the world. And when the door opened, Annabel Cray stepped out. She wore no hat. Her hair was pinned tight. Her coat clung to her frame, all sharp lines and tighter secrets.

She stood tall, lips pursed and eyes as cold as the first frost. “Good morning,” she said. Everett set his tools down and walked toward her with Clara at his side. “You didn’t write you were coming,” he said evenly. “I did,” she corrected. “You burned it.” Clara didn’t answer. Annabelle turned her gaze to her. You still here? Clara didn’t flinch. I live here.

Annabelle smiled faintly. Do you? Everett stepped in then. What do you want, Annabelle? She lifted a satchel and handed it to him. Inside were papers, clean, legal, and marked with red seals. This land, by technicality, was promised to me, she said. In your original ad, you stated the future bride would share in your holdings, and my name is on the county registry as having entered into intention with you.

I never signed anything, Everett replied. No, she agreed. But you opened a correspondence and I answered it in good faith, which means in the eyes of the Cheyenne Civil Office, we entered into a contract, and that contract gives me a claim. Boon walked up then wiping his hands on a rag.

That paper might fly in the city, but out here folks don’t give land to someone who’s never touched it. Annabelle didn’t spare him a glance. That’s why I’m not asking for it. Everett narrowed his eyes. Then why are you here? She turned her eyes back to Clara. I want her to leave. The words were plain. No rage, no insult, just a cold verdict dressed as civility. Clara’s jaws said, “You don’t get to tell me where I belong.” Annabelle folded her arms. You used my name.

You stole my place. You made a fool of my intentions and tarnished my reputation. I could ruin you in town. I could have you removed by the courts. Clara didn’t move. Then why haven’t you? Annabelle blinked just once. Everett saw it because Annabelle didn’t want to win with lawyers.

She wanted to win with shame to see Clara step down, break, apologize. But Clara didn’t break anymore. She reached into her apron and pulled out a crumpled letter. Slowly, carefully, she handed it to Annabelle. It was the first letter Clara had ever written, but never sent. I wrote this the day I arrived, she said. I was going to give it to the postmaster. I didn’t.

I was ashamed. I didn’t know how to explain what I’d done, but you can read it now. Annabelle took it, unfolded the page, and read to Miss Annabelle Cray. I do not know what kind of woman you are, but I know you deserved better than to have your place stolen. I stepped off a stage coach with nothing but a name I didn’t earn. And I stepped into a life I never expected.

What began as survival turned into something more. I fell in love with a man who saw more of me than anyone ever has, and I began to see myself through him. If you still want what was promised, I will leave. But if there’s a part of you that knows love isn’t born in letters, but in fire and trials, then I ask for your mercy.

Not for the lie I lived, but for the truth I found. Annabelle finished reading. She folded the letter. And for the first time, her voice cracked. “My father died angry with me,” she said. “He said I wasted my time dreaming of love in places that didn’t belong to me.” She looked at Everett. Maybe I was never meant for this land.

Everett said nothing. Annabelle turned to Clara. But you were. She handed the letter back. Then turned to her driver. We’re leaving. They watched the carriage disappear into the valley, its shadow long and narrow like a final word unsaid. Clara stood still for a long time, heart thutuing against her ribs.

Boon finally muttered, “Well, that was less bloody than I expected.” Everett smiled faintly. Clara looked at him. “Do you think she meant it?” He nodded. “I think she’s stronger than we gave her credit for.” Clara smiled softly. And for the first time in weeks, they all exhaled. The weeks that followed were quiet, not empty, but full of rhythm.

Boon healed slow but steady. The fences were rebuilt. New horses arrived from a ranch three counties over. The barn was painted fresh. Dusk Creek started saying the Mcallisters like it was a settled fact. One afternoon, Clara stood with Everett near the edge of the pasture. A breeze tugged at her shawl. You know, she said, “You never asked me to stay.” Everett didn’t look at her, just said.

Didn’t think I had to. She turned to him. Well, maybe I wanted to hear it. He looked back then. Stay, Clara. She smiled. I thought you’d never ask. He took her hand. No ring yet. No rush, but a promise. Not written in ink. Written in weathered hands. rebuilt barns and names earned not through letters but through fire.

Dust Creek never forgot the woman who stepped off a stage coach with the wrong name and built a life out of ashes. And it never forgot the man who pretended not to see until he truly looked together. They wrote a love story the land would carry long after their footprints vanished. The land had finally quieted, but Clara knew peace never meant permanence. Weeks passed without word from Annabelle.

The letter she’d sent burned, but the warning inside it still echoed. Yet life didn’t pause. Boon healed slowly, stubborn as ever. He repaired fences and muttered about cattle feed while Clara and Everett rebuilt the barn’s west wall. The days filled with work, the nights with silence no longer tense, but earned.

The weight of deception had lifted. The truth lived openly now and it held. One morning a letter arrived. Not for Clara or Everett, but for Boon. He read it once, then quietly packed a bag. When Clara asked, he only said, “My son found me alive. Wants me back.” No one tried to stop him. They saw it in his eyes. Something long lost returned.

Boon left with a quiet handshake, a rough hug, and a half- joking warning. Don’t let the chickens unionize. Then it was just Clara and Everett. Until Everett handed her a small box one evening at sunset. No words, just a ring, simple silver waiting. I never sent you a letter, he said. But I want you to stay. I already did, she whispered. But yes, I’ll marry you.

The wedding was small, just them, a crooked oak and Josie’s homemade pie. No fanfare, just promise. And when they kissed, the land seemed to settle deeper under their feet. Later, they sat on the porch reading Boon’s letter. My son’s got a family now. I’m building a fence. Thought I was done living. Turns out I was just waiting to start.

Clara folded the note and looked at Everett. We didn’t start right, she said. He squeezed her hand, but we ended right. And with the wind brushing through the grass and no stage coach in sight, they watched the horizon together. Home built from ashes, held by love.