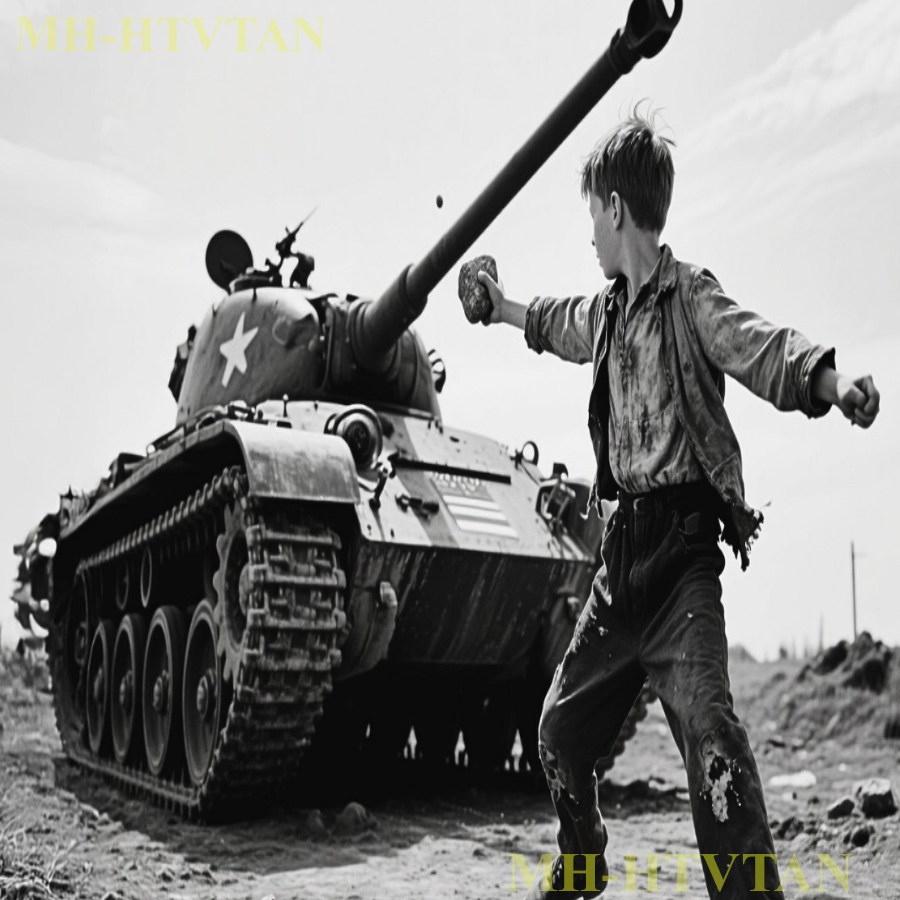

Bavaria, May 1945. The Sherman tank rolled through the rubble line street of Garmish. Its engine growling low and steady. Dust rose from crushed brick, hanging in the air like fog. From behind a collapsed storefront, a rock sailed through the afternoon light small, jagged, thrown with all the fury a 12-year-old boy could muster. It struck the tank’s hall with a hollow clang that echoed between the ruined buildings.

The turret stopped rotating. The hatch opened and Lieutenant James Sullivan climbed out holding not a rifle but a baseball and a warm leather glove. What happened next would be written in a boy’s diary for 70 years. Garmish partners sat in the shadow of the Bavarian Alps like a postcard that had been torn and burned. Before the war, it had been famous for winter sports.

The 1936 Olympics had showcased the town ski slopes and alpine charm to the world. Tourist hotels lined streets were wealthy. Europeans came to breathe mountain air and pretend the century troubles did and exist. By May 1945, those hotels were rubble or requisitioned military billets. The ski slopes remained, but the gondilas hung still and broken.

The streets were cratered from American artillery. Windows gaped empty where glass had shattered during the final push into southern Germany. The American Third Army had taken the town on April 30th. Resistance had been minimal, a few scattered defensive positions. some half-hearted mortar fire, then white flags appearing in windows as soldiers who had fought for six years decided they had fought enough.

The formal German surrender came a week later, but in Garmish, the war had already ended with a whimper of exhaustion rather than any dramatic conclusion. Lieutenant James Sullivan’s tank platoon had been assigned occupation duty in the town. Four Sherman tanks, 16 men responsible for maintaining order in a population that ranged from sullenly, cooperative to openly hostile depending on the day and the individual. Sullivan was 24 years old from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

He had joined the army in 1942, trained at Fort Knox, landed at Normandy three weeks after D-Day. He had fought across France and into Germany, had seen friends die, had developed the thousand-year stare that combat veterans carried like scars. He was tired, bone tired, soul tired, ready for the war to truly end so he could go home and try to become whoever he was before tanks and destruction had reshaped him.

The tank he commanded nicknamed Pittsburgh Steel by his crew was parked in the town square each morning as a visible reminder of American authority. The crew took shifts manning it more for show than necessity. The real threats to occupation came not from German military resistance, but from displaced persons, black market operations, and the general chaos of a society that had collapsed.

On May 15th, Sullivan was in the turret performing routine maintenance when he heard the distinctive sound of a rock striking steel. Klaus Vber was 12 years old and angrier than he had words to express. His father had died in Russia. He didn’t know when exactly the letter had said, only that Hans Vber had fallen in the east.

Details to follow, condolences from the German leadership. No details had followed. The leadership had collapsed. His father was simply gone, erased, transformed from a person into a statistic. His mother worked at the American Mess Hall, cleaning dishes and floors for occupation forces because it was the only job available and because they needed food.

She came home each evening smelling like American soap and cigarette smoke, her hands raw from harsh detergent, her eyes empty of everything except exhaustion. Their apartment building had been hit during the American artillery barrage. They now lived in three rooms of what had been a six- room flat. The other half opened to the sky where the roof had collapsed.

When it rained, they moved furniture to avoid the leaks. When the sun shone, the ruined half of their home glowed with the golden light of defeat. Klouse had been taught to hate Americans. The propaganda had been relentless. Americans were barbarians, wararmongers, culturally inferior, racially mixed, decadent, weak, and simultaneously somehow dangerous enough to require total war to defeat.

The contradictions didn’t matter. What mattered was the message. Americans were the enemy. And now they occupied his town, drove their tanks through his streets, handed out chocolate to children who begged, employed his mother to scrub their floors. The humiliation was physical. Klouse felt it in his chest like something crushing his lungs.

He couldn’t articulate why a tank parked in the town square enraged him so deeply, but it did. The machine sat there like a monument to German defeat. Its American crew lounging nearby, smoking cigarettes, laughing about things Klouse couldn’t understand. On May 15th, walking home from the distribution point where he had waited 3 hours for bread rations, Klaus saw the tank and something inside him snapped.

He picked up a piece of rubble brick fragment, jagged, heavy enough to throw with force, and hurled it at the machine with all the strength his 12-year-old body could generate. The rock struck with a satisfying clang. Klouse felt a moment of fierce joy, then terror, then defiance. He stood in the open, breathing hard, waiting for punishment. The turret hatch opened.

An American soldier emerged. Klouse expected a rifle, expected shouting, expected to be dragged away like he had seen other Germans dragged away for infractions against occupation authority. Instead, the American climbed down from the tank holding a baseball and a leather glove that looked old and wellused.

He walked toward Klaus with an expression that was neither angry nor friendly, just curious. Klouse stood frozen, unable to run, unable to speak. The Americans stopped 10 ft away. He tossed the baseball from hand to hand considering. Then he spoke in slow, careful English. “You got a good arm, kid.” Klouse understood no English. He stared, confused and frightened.

The Americans seemed to realize this. He held up the baseball, mind throwing it, then pointed at Claus, pointed at himself, made a gesture that suggested exchange. Claus’s brain struggled to process what was happening. He had thrown a rock at an American tank. The American wanted to dot dot dot play catch. Lieutenant Sullivan had not planned to teach baseball to a German kid.

He had simply reacted on instinct when the rock hit his tank climbed out to identify the threat. Saw a skinny boy with defiant eyes and fists clenched and recognized something he had seen before. Fear masquerading as anger. Grief expressing itself as aggression. A child trying to control something, anything in a world, and it spiraled beyond all control.

Sullivan had two younger brothers back in Pittsburgh, 13 and 15 when he shipped out, probably 17 and 19 now, if they were still alive, which he prayed they were, even though he hadn’t received mail in weeks. He knew what boys look like when they were hurting. This German kid was hurting. The baseball in Sullivan’s pocket was a relic from another life.

He had carried it through France and Germany like a talisman a connection to normaly to afternoons in Forbes field watching the pirates to a world where the most important thing was whether a fast ball crossed the plate or missed outside. He hadn’t thrown it in months. Hadn’t even thought about baseball in any meaningful way.

But seeing the kid standing there radiating fury and fear, Sullivan thought, “Maybe this is how you start rebuilding, one throw at a time.” He mimed throwing again, more elaborately, wound up like a pitcher, released an imaginary ball, followed through with exaggerated motion. Klouse watched, utterly baffled. Sullivan’s crew had emerged from their positions around the square, watching this strange confrontation.

Corporal Miller called out. Lieutenant, what the hell are you doing? Teaching, Sullivan replied. Or trying to. He took a few steps back. Creating distance. Then he gently tossed the baseball toward Klouse underhand, slow, easy to catch. Klouse flinched. The ball bounced off his chest and rolled to his feet.

He looked down at it like it might explode. Sullivan gestured, “Pick it up. Throw it back. Klouse bent slowly, picked up the baseball. It felt foreign in his handstitched leather, smaller than he expected, waited strangely. He had no idea what he was supposed to do with it. Sullivan held up his glove, showed the pocket, demonstrated catching, then pointed at Klouse, made a throwing motion.

Klouse, operating purely on confused instinct, threw the ball back wildly, inaccurately, but with reasonable force. It sailed past Sullivan’s head. Sullivan retrieved it, smiling slightly. Good arm, bad aim. We can work on that. Word spread through Garmish with the speed of all gossip in small towns. The American tank commander was playing with Klaus Vber, with the Vber boy, the one whose father died in Russia, the one who threw rocks at the occupation forces.

People emerged from damaged buildings to watch. Some disapproving, some curious, some simply grateful for entertainment that wasn’t grim. Children especially drawn by the sight of a ball being thrown, a game being played, something that looked like normaly. Klouse’s mother, Margareti, was finishing her shift at the mess hall when someone told her.

She dropped the plates she was carrying and ran toward the town square, heart hammering with fear. Klouse had done something stupid. Klouse was in trouble. Klouse was going to be arrested or hurt, or she arrived to find her son standing in the street throwing a baseball back and forth with an American officer while a crowd of Germans and American soldiers watched like this was some kind of sporting event.

Klouse, she called out in German, “What are you doing?” Klouse turned at his mother’s voice, missed Sullivan’s throw. The ball rolled past him. He looked torn between shame and something else. Something that might have been the first hint of joy she deen in him since his father s death notice arrived. Sullivan retrieved the ball again. Noticed the woman who had called out.

He walked over to her, removed his helmet in a gesture of respect. “Ma’am,” he said, “your boy’s got a good arm. Just needs practice.” Margaretti understood no English, but she understood the tone call, almost friendly, not angry, not punishing. Klouse threw rock. She managed in broken English, one of perhaps 10 phrases she had learned at the mesh hall.

He is sorry, Sullivan looked at Klaus, who definitely did not look sorry. Then back at Margaret. No harm done, Sullivan said. Just teaching him a better way to throw things. He mimed pitching again, showed her the baseball. Then, in an impulse he didn’t entirely understand, he handed her the ball. Give this to him.

Tell him to practice. Margaret held the baseball like it was something precious and dangerous. She looked at her son at the American at the crowd watching this bizarre exchange. “Thank you,” she said carefully. Then in German to Klouse, “Come now,” Klouse followed his mother home. Glancing back at Sullivan at the tank, at the baseball his mother clutched, he felt confused and angry, and somehow, inexplicably less alone than he had felt in months.

Klouse didn’t sleep that night. He lay in his bed in the half-ruuined apartment, listening to rain drip through the damaged ceiling into the pots and pans. his mother had positioned to catch it. He kept thinking about the American and the strange game with the thrown ball.

His mother had been silent on the walk home, not angry exactly, but troubled. When they reached the apartment, she placed the baseball on the small table by the window and stared at it for a long time. Why did you throw the rock? She asked finally. Klouse had no good answer. Because I’m angry. Because father is dead. Because Americans destroyed our city. Because everything is ruined and I cry and fix it.

And I needed to break something. Even if it was just a rock against steel. He said, “None of this. Just I don’t know.” Margaretti picked up the baseball, turned it over in her hands. The leather was worn smooth in places, the stitching tight and precise. It looked old but cared for. That American could have arrested you, she said quietly. Could have punished you.

Instead, he gave you this. I don’t understand why. Klouse didn’t understand either. Nothing about the encounter made sense according to the rules he had been taught. Americans were supposed to be cruel occupiers. The propaganda had been explicit. And yet the man in the tank had responded to aggression with dot dot play, with teaching, with a gift.

The next morning, Klaus returned to the town square. He told himself he was just passing through, just happening by, but he was holding the baseball. Sullivan was there performing maintenance on the tank. When he saw Klouse approach, he smiled. Morning, kid. Klouse stood at a distance uncertain.

Sullivan climbed down from the tank, retrieved his glove from inside the hull. Want to try again? Klouse didn’t understand the words, but understood the gesture when Sullivan tossed the ball gently. This time, Klouse caught it clumsily with both hands, but he caught it. Sullivan whooped, startling Klaus. Good catch. Now throw it back. They fell into a rhythm. Throw, catch, throw, catch.

Sullivan gradually increased the distance, teaching through demonstration. He showed Klouse how to grip the ball across the seams, how to step into the throw, how to follow through. Klouse was a quick study. Within an hour, his throws were straighter, stronger. Sullivan found himself genuinely impressed. “You’re a natural,” Sullivan said.

in another life you’d make a hell of a picture. Klouse understood nothing except that the Americans seemed pleased and somehow that mattered. Over the following weeks a pattern developed. Klouse appeared in the town square most mornings. Sullivan, when his duties allowed, spent time throwing with him.

They couldn’t speak each other’s language beyond gestures and the occasional borrowed word, but they communicated through baseball. Sullivan taught close the basics throwing, catching, the concept of a strike zone. He drew a rectangle in the dirt to represent home plate, showed Klouse how to aim. They didn’t have bases or a full field, just a damaged street and two people throwing a ball, but it was enough.

Klouse began to understand the game’s structure. Three strikes, four balls, outs and innings. Sullivan demonstrated batting with a broken piece of lumber, showed Klouse how to swing. They played a bastardized version of baseball with whatever they could improvise rocks for bases, rubble piles for foul lines.

Other children began watching, then tentatively joining. American soldiers, too, drawn by nostalgia for a game that represented home and normaly. By June, there were pickup games happening in the town square. Germans and Americans, children and soldiers playing baseball in the ruins of a town that was slowly, painfully beginning to rebuild.

Corporal Miller Sullivan’s gunner joined one game and found himself pitching to a German boy who couldn’t speak English, but who could somehow blunt. The absurdity of it playing children’s games with former enemies while Europe lay in ruins was almost overwhelming. This is insane. Miller said between innings. Sullivan playing first base shrugged. Maybe.

But look at them. The children Klouse and a growing group of German kids were laughing. Actually laughing, running bases, arguing about what constituted fair or foul, completely absorbed in the game. That’s the first time I’ve seen kids here look like kids, Sullivan continued. Not like refugees. Not like orphans. Just kids. Miller nodded slowly. Still insane.

Yeah, but maybe the good kind. Not everyone approved. Some Germans saw the baseball games as collaboration, as betrayal of national pride. Klouse faced taunts from older boys who had been in the Hitler youth who maintained fierce loyalty to the defeated regime’s ideology. American traitor.

They hissed when Klouse walked past playing with the enemy while your father lies dead in Russia. Klouse tried to ignore them, but their words burned. Was he betraying his father’s memory, his country? Was there something shameful about finding joy in a game taught by occupiers? He asked his mother one evening. Father would hate this, wouldn’t he? Me playing with Americans.

Margareti was mending a shirt by candlelight electricity remained intermittent. She set down her needle and looked at her son. “Your father,” she said carefully, “died for leaders who lied to us. Who told us we were superior and destined to rule. Those leaders destroyed our country, Clouse. They destroyed millions of lives. Your father believed them because he was told to believe them.

” She paused, choosing words with care. That American who teaches you baseball, Lieutenant Sullivan, he could treat us with cruelty. The occupation could be harsh, punishing. Instead, he throws a ball with children. He shares something from his home. Your father would want you to live, Claus, to find reasons to smile, to rebuild. I think he would understand.

But on the American side, there was also resistance. Captain Richard Warren, Sullivan’s commanding officer, called him in after reports of the baseball games reached higher command. Lieutenant, I’ve been getting complaints. You’re fraternizing with German civilians beyond operational necessity. Sir, I’m playing baseball with kids.

You’re creating unauthorized recreational activities with former enemy populations. There are protocols about this, sir. with respect. The war is over. These kids aren’t enemy combatants. They’re children who’ve lost everything. Baseball costs nothing and gives them something positive to focus on. Warren leaned back in his chair. You’re aware that some of these children’s fathers may have fought against us, may have been responsible for American deaths? Yes, sir.

And my father fought against Germans in World War I. Should I hold children responsible for their father’s wars? Warren had no immediate answer to that. Finally, keep it controlled. No large gatherings, no publicity. And if there’s any incident, any problem, it stops immediately. Understood, sir. But Warren’s expression suggested he understood more than he was saying.

That maybe he too saw value in children playing instead of moring. By July, the informal games had evolved into something resembling organized baseball. Two teams mixed German and American playing regular matches. Sullivan had acquired additional equipment through creative requisitioning. More gloves, actual bats, even a catcher mask that was decades old but functional.

Klouse had become the best German player. His pitching had improved dramatically. He could hit Sullivan’s improvised strike zone with reasonable accuracy, could throw a curveball that wasn’t technically correct, but was effective enough to confuse batters. More importantly, he had regained something that resembled childhood.

He smiled now, argued about calls with passionate insidi, celebrated successful plays with unguarded joy. Margaret watched one game from the edge of the square. She saw her son dive for a ground ball, come up dirty and grinning. Heard him shouting in German and broken English mixed together as language barriers dissolved in the heat of competition. A voice beside her said in accented German, “He’s good.

” She turned to find Lieutenant Sullivan standing nearby, watching the game with an expression of quiet satisfaction. Thank you, Margareti said, for teaching him, for being kind. Sullivan switched to slow, careful English. He’s a good kid. Reminds me of my brothers. Brothers? Back home? Pittsburgh.

I hope they’re playing baseball right now instead of He gestured vaguely at the ruined buildings around them. Margaret understood. War, she said in English. Is finished. We must. She struggled for the word, then mimed, “Rebuilding.” “Build,” Sullivan supplied. “Yeah, we must build.” They watched the game in companionable silence. Klouse struck out an American corporal with three straight pitches. The corporal laughed, shook Klaus’s hand, said something that made Klouse laugh in return.

“Your boy’s got a future in baseball,” Sullan said. “If he wants it.” Margaret didn’t understand all the words, but understood the approval in Sullivan’s tone. She smiled, and for the first time in years, it was enforced. In August, Sullivan proposed something ambitious, a proper tournament. German teams versus American teams played over a week with actual standings and a championship game.

The idea was met with resistance from both sides. German adults worried it would emphasize divisions. American command worried about fraternization regulations. Children on both sides worried they weren’t good enough. Sullivan persisted. He organized teams, established rules, created a schedule.

He designated the town square as the stadium and cleared rubble to create something approximating a real field. The tournament began on August 10th. Four German teams, four American teams, single elimination format. The rules were adapted for available space and equipment, but the spirit was authentic. Klaus’s team die Adler.

The Eagles faced an American squad in the first round. The game was tense, competitive, absurdly intense for what was essentially children and young soldiers playing in rubble. Klouse pitched all seven innings. His arm hurt by the fifth, but he refused to come out. He struck out the last batter with a pitch that barely qualified as a curveball, but caught the corner of the strike zone. Sullivan had drawn in lime powder. Diadler won four to three.

Claus’s teammates mobbed him, shouting in German and English. American players came over to shake hands, congratulate them on good play. The sportsmanship was genuine, spontaneous, unmarred by the context of recent enmity. The tournament continued through the week. Attendance grew.

Germans and Americans coming to watch, drawn by the novelty and the genuine quality of play. Someone brought benches from a destroyed church to create seating. A local woman started selling water and bread to spectators, creating an impromptu concession stand. By the championship game, the event had taken on significance beyond baseball. It had become a symbol of something reconciliation maybe, or at least the possibility of moving forward.

The final matched Klaus’s Eagles against an American team led by Corporal Miller. The game was scheduled for Saturday, August 18th. The morning of the championship game dawned clear and bright. Alpine peaks visible in the distance. Sky so blue it hurt to look at. The kind of day that made devastation seem temporary it suggested beauty could survive anything.

The town square filled early. Spectators, German civilians, and American soldiers crowded around the improvised field. Someone had created bunting from scavenged fabric, strung it between ruined buildings in red, white, and blue that could have been American or could have been German depending on interpretation. Sullivan served as umpire, a role he took seriously.

He wore his uniform but left his helmet off, stood behind the pitcher, calling balls and strikes with theatrical authority. Klouse took the mound for the Eagles. Across the field, Miller’s teen prepared to bat. The cultural symbolism was too obvious to ignore. German boy pitching to American soldiers in a town destroyed by war.

Playing a game neither side had known three months earlier. The first pitch sailed wide. Ball one. Klouse settled. Found his rhythm. The next pitch caught the corner. Strike. The game unfolded with surprising intensity. Both teams played well better than expected given their limited experience.

Klouse pitched effectively, mixing fast balls with his experimental curve. Miller’s team countered with disciplined hitting and aggressive base running. By the sixth inning, a score was tied 2 to2. Tension built with each pitch. Spectators shouted encouragement in German and English. The atmosphere felt momentous, though no one could quite articulate why a children’s baseball game mattered so much.

In the bottom of the seventh final inning, by their abbreviated rules, the Eagles had runners on second and third with two outs. Klouse came to bat. He had never been a strong hitter. His talent was pitching, but the moment called for something, and sometimes moments create their own necessity. Miller’s pitcher threw a fast ball down the middle.

Klaus swung late, fouled it off. Strike one. The next pitch was outside. Klouse watched it pass. Ball one. The third pitch came in high and tight. Klouse stepped back, started to swing, stopped. The ball caught the outside corner. Strike two. The square went silent.

Klouse gripped the bat a salvaged piece of wood that Sullivan had sanded smooth and waited. The pitch came in perfect, not too fast, not too slow, right down the heart of the strike zone. Klouse swung. The sound of bat meeting ball echoed between ruined buildings. The ball sailed over the infield, over the outfield, cleared the improvised fence of rubble, and landed somewhere in what had been a destroyed bakery. Klouse stood frozen, unsure what he had done.

Run! Sullivan shouted. “Kid, run!” Klouse ran, touched first base, second, third, his teammates mobbed him at home plate. Germans and Americans both cheering, the distinction momentarily irrelevant in the face of athletic excellence. The Eagles won 4 to2. Sullivan had prepared something for the championship conclusion.

He had spent weeks carving a trophy from wood, salvaged from destroyed buildings, a baseball player midswing, mounted on a base inscribed with the words Garmish tournament champions, August 1945. He presented it to Klouse in front of the assembled crowd. Klouse accepted it with hands that trembled, eyes wide with disbelief. “You earned this,” Sullan said in English.

You played fair, played hard, played well. That’s what baseball is about. Helga translated in real time, though Klaus barely needed translation. He understood from Sullivan’s tone, from the weight of the trophy, from the applause echoing around the square. “Thank you,” Klaus said in careful English. “Thank you for teaching.” Sullivan shook his hand.

“Thank you for learning.” Then Sullivan did something unexpected. He called Miller over, removed a patch from his own uniform, the Third Army insignia, and pinned it to Klaus’s shirt. “Brothers in baseball,” Sullivan said. “That’s what we are now.” The gesture was small but profound.

Klouse touched the patch, feeling the embroidered thread, understanding that something had shifted. He was still German. Sullivan was still American. But another identity baseball player had been added to both of them, creating connection across the chasm of war. The crowd dispersed slowly, Germans and Americans lingering, talking, some exchanging addresses for future correspondence.

The rigid boundaries between occupier and occupied had softened, not disappeared, but made more porous by shared experience. Klouse walked home with his mother and the wooden trophy. They placed it on the table by the window next to the baseball Sullivan had first given him months earlier. “What does this mean?” Klouse asked.

“The trophy, the games, all of it,” Margaretti considered. “I think it means we’re allowed to rebuild. Not just buildings, but ourselves.” “That American taught you more than baseball, Klaus. He taught you that enemies can become dot dot dot something else. Not friends exactly, but not enemies anymore either. What word is there for that? Margaretti smiled.

Maybe we need to invent a new word. Sullivan’s orders came in September. The Third Army was rotating units, sending occupation forces home, bringing in new personnel. His platoon would ship out within 2 weeks. He told Klouse on a Tuesday afternoon. They were throwing in the square. Routine practice that had become daily ritual.

I’m leaving soon, Sullivan said. Going home. Klouse understood. Leaving and home, if not the full sentence. His expression fell. Pittsburgh, Sullivan continued, pointing east. My family, my brothers. He mimed playing baseball, pointed at Klouse, then at himself, trying to convey that they both would continue even apart. Klouse nodded. Understanding and not understanding.

He had known this would happen. Occupying forces wouldn’t stay forever. But knowing didn’t make it easier. On Sullivan’s last day in Garmish, the entire baseball community, German and American players, gathered for a final game. Not competitive, just exhibition. Everyone played, positions rotated. The score didn’t matter.

Afterward, Klaus presented Sullivan with a gift a journal his mother had helped him create. Inside, Klaus had drawn pictures of their baseball games had written in German about what Sullivan’s teaching had meant. Sullivan couldn’t read German, but he understood from the drawings. He felt his throat tighten. I’ll keep this forever, he said.

And when I get home, I’ll tell my brothers about the German kid who learned to pitch in three months. Klaus handed Sullivan the original baseball, the one Sullivan had given him that first day. Sullivan tried to refuse, but Klouse insisted. “You gave it to me,” Klouse said in broken English. “Now I give back, so you remember.

” Sullivan accepted the ball, worn now for months of use, carrying the marks of their shared experience. I’ll remember, Sullivan promised. Kid, I’ll remember everything. They shook hands. Then, impulsively, Sullivan pulled Klouse into a brief hug. Klouse stiffened with surprise, then relaxed, returning the embrace. The Americans departed the next morning.

Klouse watched from the town square as the tanks rolled out, heading northwest toward staging areas and eventually ships home. Pittsburgh Steel passed last. Sullivan stood in the turret, saw Klaus watching, and threw a final salute. Klouse saluted back, formal and precise.

Then the tanks were gone, leaving only the sound of engines fading into distance, and the baseball field they had built together in the ruins. Klaus Vber continued playing baseball. When organized leagues formed in postwar Germany, he joined immediately. By 1950, he was playing semi-professionally for a Munich team. He never became famous baseball, remained a minor sport in Germany, but he played well and loved it fiercely.

He kept the wooden trophy on his desk for the rest of his life. Brought it to university, to his first apartment, to the home he shared with his wife, and eventually children. When grandchildren visited, he told them about the American who taught him baseball in the ruins of Garmish. James Sullivan returned to Pittsburgh.

He married, had children, worked as a machinist in a steel mill. He kept Klouse’s journal in a box of war memorabilia that he rarely opened but never discarded. Sometimes he would take out the baseball worn smooth from use, stitching coming loose, and remembered teaching a German kid to pitch.

In 1967, Sullivan received a letter forwarded through military channels. It was from Klouse written in improving English explaining that he had found Sullivan’s address through determined research. The letter described Klaus’s life, his family, his career, his continued love of baseball.

Sullivan wrote back, “They corresponded irregularly over the years, Christmas cards, and occasional letters. The friendship was distant, but genuine, maintained across language barriers and geographic distance. In 1985, Klaus traveled to the United States for a baseball tournament. He detoured to Pittsburgh, met Sullivan for the first time in 40 years.

They were both 62 years old, gay-haired, carrying the weight of decades, lived since that summer in Garmish. They spent an afternoon at Forbes Field, the same stadium where Sullivan had watched games as a boy. They threw a baseball back and forth in the parking lot, their arms weaker, but the muscle memory intact. Remember when I threw that rock at your tank? Klouse asked. Sullivan laughed.

Best recruiting I ever did. Turned an enemy into a pitcher. They talked about the war, about the years after, about what that summer had meant. Sullivan had gone on to coach little league, had taught hundreds of children to play. Klouse had done the same in Germany, spreading the game Sullivan had brought to Garmish.

You changed my life, Klouse said. I was so angry, so lost. Baseball gave me something to build instead of destroy. Sullivan shook his head. You changed your own life. I just provided the ball. But that’s what it took. The ball. The willingness to teach an enemy’s child. The grace of responding to a rock with a game.

They played catch until evening. Two old men throwing a baseball in a Pittsburgh parking lot. Connected by a moment in Bavarian ruins when anger met kindness and baseball provided the language they both needed. Klaus Vber died in 2015 at the age of 82.

Among his possessions, the wooden trophy Sullivan had carved, the third Army patch Sullivan had pinned to his shirt, and 70 years of journals documenting his love affair with baseball. James Sullivan died in 2003 at the age of 81. Among his possessions, Claus’s handdrawn journal from 1945, the baseball they had played with in Garmish, and photographs of the championship game that someone had taken and sent to him decades later.

The town square in Garmish Park in Kurchin has been rebuilt multiple times over the decades. No trace remains of the improvised baseball field, the line drawn strike zones, the rebel pile bases. But in the town museum, there is a small exhibit about the summer of 1945.

It includes photographs of German and American children playing together, a worn baseball that was donated anonymously, and text describing how an American tank commander responded to a thrown rock, not with punishment, but with a game. The exhibit’s title, When Enemies Became Teammates. Historians debate the significance of the Garmish Baseball Games. Some see them as footnotes, minor feel-good stories in the larger narrative of occupation and rebuilding.

Others argue they represent something essential about reconciliation, the need for small human connections to bridge divides that war creates. But perhaps the meaning is simpler than academic analysis suggests. A 12year-old boy threw a rock because he was angry and hurt and powerless. An American lieutenant could have responded with punishment. Instead, he responded with a baseball.

From that exchange, months of games, a lifetime of friendship, and the slow, painful understanding that enemies are created by circumstance, but humanity is chosen by individuals. Klouse kept playing until arthritis made throwing impossible. Sullivan coached until Parkinson’s made standing difficult. Both men carried the memory of that Bavarian summer as proof that even in war’s aftermath, kindness could defeat hate one pitch at a time.

The rock Klaus threw bounced off Pittsburgh steel and fell into dust. The baseball Sullivan handed him traveled across decades, across oceans, across the impossible distance between enemy and friend. One was a weapon, the other was a gift. Klouse chose the gift and in choosing helped prove that the future didn’t have to be defined by the past’s hatreds.

Sometimes the most important battles are won not with thanks but with patience. Not with violence but with a leather glove and a willingness to teach. Not with punishment but with the radical act of responding to a child’s anger with grace. The war ended in May 1945. But the healing began with a baseball in August thrown between two people who should have been enemies but chose to be something better.

Players, teachers, students, friends, brothers in baseball, as Sullivan had said. And in being brothers in baseball, they proved that brotherhood was possible even across the deepest divisions war could create.