October 14th, 1943. 25,000 efted above Shvine Fort, Germany, Technical Sergeant Robert Bobby Mitchell pressed his face against the frozen plexiglass of his B7’s waist gun position, watching tracer rounds arc gracefully through the thin air, missing the approaching Faka Wolf 190 by what seemed like 100 Vaft, the German fighter rolled away unscathed, its yellow nose mocking him as it banked for another pass.

Mitchell cursed himself for leading the target exactly as he’d been taught in gunnery school back at Las Vegas Army Airfield just 6 months earlier. Everything he’d learned about marksmanship, everything drilled into him since basic training at Keysler Field, Mississippi, was failing him catastrophically.

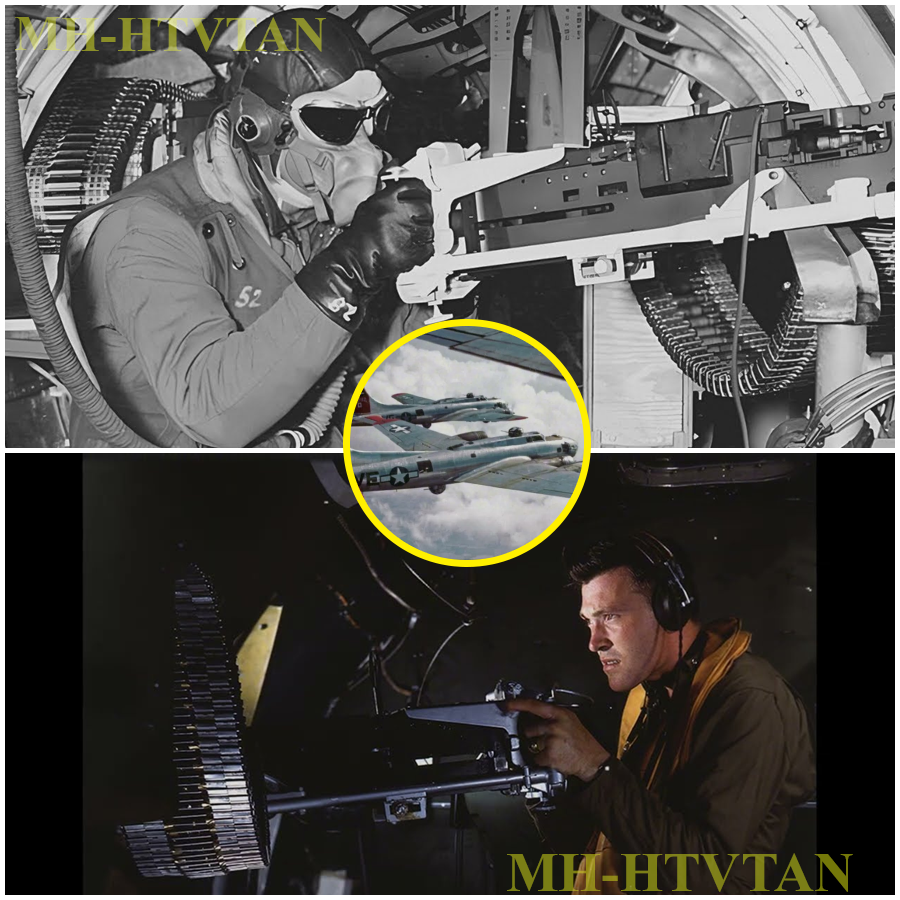

In three missions over Germany, he hadn’t hit a single fighter despite firing over 4,000 rounds. Neither had most of the other gunners in his squadron. The mathematics of failure were becoming undeniable. American bombers were being shot down at unsustainable rates while their gunners were hitting almost nothing.

What Mitchell didn’t know, couldn’t know in that moment of frozen terror was that 2,000 m away in a collection of hastily constructed buildings at Eglundfield, Florida, teams of mathematicians, physicists, and ballisticians were completing revolutionary calculations that would transform the entire nature of aerial combat. Within 8 weeks, American gunners would stop aiming at German fighters entirely.

They would cease trying to track individual targets through their sights. Instead, they would spray calculated patterns of bullets into predetermined zones of empty space, trusting mathematical probability over traditional marksmanship, statistics over skill.

And they would begin destroying German fighters at rates that would shock even the most optimistic American planners and terrify the Luftvafa high command. The coming revolution would shatter every sacred principle of marksmanship stretching back a thousand years to Chinese alchemists and their first gunpowder. Forget sight pictures. Abandon trigger discipline. Stop tracking targets. Throw out everything about leading your prey. What emerged from desperation bordered on heresy.

Fire thousands of rounds into empty sky where no enemy exists. Trust the mathematics of probability distributions. watched German fighters hurdle into invisible walls of lead they never saw coming. The breaking point arrived August 17th, 1943. That morning, 376 B7 flying fortresses of the Eighth Air Force lifted off in two massive waves bound for the Messor Schmidt works at Reagansburg and Schwinfort’s ballbearing plants. Months of planning had gone into this decisive strike against German industry. By sunset, the

numbers told a catastrophic story. 60 bombers shot down, most to savage fighter attacks lasting hours. Another 95 so badly damaged they’d never fly again. Over 600 airmen dead, wounded or missing. The surviving gunners claimed 288 German fighters destroyed, another 27 probable.

Post war, Luwaffa records revealed the truth. Between 25 and 27 actual kills, American gunners were missing more than 90% of their claimed targets, burning thousands of rounds for every confirmed kill. Staff Sergeant William Crossman of the 100th Bomb Group, one of the few who definitively destroyed an enemy fighter that August day, wrote something that would later haunt operations researchers.

I fired at 12 different aircraft. I’m certain I destroyed one, saw it explode, watched the pilot bail out. The other 11 might as well have been throwing rocks. My tracers followed them perfectly across the sky, but never connected. Like they had invisible shields, were fundamentally wrong about something.

The roots of this disaster traced back to the optimistic inter war years when Army Airore theorists fell in love with precision daylight bombing. Influenced by Italian General Julio Duhei’s prophecies of strategic bombing winning wars independently, they convinced themselves heavily armed bombers could fight through to any target without escort. The B7 Flying Fortress, first airborne from Boeing Field in Seattle, July 1935, embodied this seductive theory.

Eventually bristling with 1350 caliber machine guns creating interlocking fire, bombers would fly tight defensive formations, their combined firepower and impenetrable hedge. Elegant theory, thoroughly war gamed at Maxwell Field, about to cost thousands of American lives.

Lieutenant Colonel Harold Bowman commanded flexible gunnery training at Las Vegas Army Airfield. By January 1942, weeks after Pearl Harbor, he had identified the fatal flaw. His classified report, sealed until 1972, showed remarkable precience. We’re training our gunners to shoot rifles at 300 yards when they desperately need shotguns at 30 ft. Our entire foundation is wrong.

applying 19th century marksmanship to 20th century aerial combat. The boys we’re sending to England are going to die because we’re teaching them the wrong skills. Bowman understood through careful analysis what physicists would later confirm through rigorous calculation. Modern aerial combat had rendered traditional marksmanship obsolete.

When a Messor Schmidt 109 attacked from 12 high, straight ahead, slightly above, combined closing speeds could exceed 600 mm. The fighter covered 880 ft every second. A gunner had maybe two seconds from threat identification until the fighter passed out of range. At those speeds, human eyes couldn’t track fast enough. Brains couldn’t calculate deflection quickly enough.

Trigger fingers couldn’t respond precisely enough. The mathematics were unforgiving and absolute. A Faka Wolf 190 attacking from the classic 12 high covered those 880 ft per second. A 50 caliber bullet traveled 2,810 ft pers at sea level. But at 25,000 ft in air only 1/3 as dense, velocity and trajectory changed dramatically.

The bullet had to arc through space while both bomber and fighter moved in three dimensions at different speeds and angles. Factor in the bomber’s forward speed of 180 to 250 mh depending on loading and altitude. account for gravitational drop over distance, wind resistance shifting with altitude and temperature, parallax error between the gunner’s eye and gun muzzle, sometimes several feet apart.

The gunner faced a trigonometric equation with at least 14 variables that would challenge modern computers to solve in real time. Technical Sergeant James Morrison of the 94th Bomb Group had been a Cincinnati high school math teacher before the war. He spent weeks calculating these variables in spare time.

His notebook, discovered in the National Archives in 1987, contained pages of equations attempting to solve the gunnery problem. His conclusion, scrolled in frustration, were asking farm boys from Iowa and factory workers from Detroit to be calculating machines. We’re demanding they solve differential equations in their heads while being shot at. It’s not just difficult, it’s impossible.

The first hint that something radically different might work came from an unlikely source in early September 1943. Master Sergeant Anthony Kowalsski was a dimminionive ball turret gunner with the 91st Bomb Group at Bassingorn, England. After his fifth mission over Germany, he’d given up on traditional aimed fire entirely.

The ball turret, that plexiglass bubble hanging beneath the B7’s belly, was perhaps the most terrifying position in the aircraft. Kowalsski would curl fetal inside this sphere, surrounded by ammunition feeds and hydraulic lines. Nothing between him and 25,000 ft of empty air, but thin plastic. He couldn’t wear a parachute, no room. If the turret jammed, he’d ride it down to his death.

Perhaps this constant proximity to death freed him from training’s constraints. Instead of carefully tracking individual fighters through his reflector site, he developed what he called the garden hose method. When German fighters approached, he’d simply spray bullets in their general direction, walking his tracers across their anticipated flight path like water from a high pressure hose, filling the air with lead and letting the Germans fly into it.

His fellow gunners mocked him initially called him spray and prey Tony. September the 6th, 1943, a maximum effort mission over Stoutgard. Kowalsski’s unorthodox method produced extraordinary results. In four minutes, he shot down two Messers 110 twin engine fighters and damaged a third. So severely, it was last seen trailing smoke, diving away from formation.

Intelligence officers debriefed him after the mission. Kowalsski couldn’t explain precisely how he’d done it. I wasn’t aiming at them in the traditional sense, he admitted. Thick Chicago accent making his words difficult for the Harvard educated intelligence officer to parse.

I wasn’t tracking them through my sight or calculating lead. I just filled the air where I thought they’d be with as many bullets as possible and let them fly into it like they were committing suicide on my bullet stream. Kowalsski’s remarkable success caught Major William Becker’s attention, a former MIT physics professor serving with the ETH Air Force’s operational research section.

This unit modeled on similar British organizations that had revolutionized anti-ubmarine warfare applied rigorous mathematical analysis to combat problems. Becker had been analyzing thousands of feet of combat camera footage, studying the geometry of fighter attacks and bomber defensive fire. What he discovered challenged everything the Army Air Forcees believed about aerial gunnery.

His report dated September 15th, 1943, classified most secret, distributed only to senior commanders, stated, “Our analysis of 1,247 combats between B17 formations and German fighters, reveals a disturbing truth. The most successful gunners, those who actually destroy enemy aircraft rather than simply claiming them, are not the ones with highest marksmanship scores from training.

They’re not the ones who carefully track targets through sights. They’re almost universally the ones who fire the most ammunition in the shortest possible time, regardless of traditional accuracy. Traditional deflection shooting requires the gunner to calculate where the target will be and place a bullet precisely there.

But what if instead of trying to aim at where we think the enemy will be, we simply fill every place he could possibly be with bullets? What if we stopped trying to achieve precision and instead pursue probability? The theoretical breakthrough came from an unexpected source. Captain Robert Lindseay, a thin, nervous statistical analyst who’d worked as an actuary for Metropolitan Life Insurance before the war.

Lindsay understood probability in ways traditional military officers did not. Insurance companies lived or died on their ability to predict aggregate behavior, even when individual actions remained unpredictable. At a meeting at 8th Air Force headquarters at High Wikcom on September 22nd, 1943, Lindseay presented his revolutionary theory to a room full of skeptical senior officers.

Gentlemen, he began, voice shaking slightly as he faced an audience, including General Ira Eker, commander of the Eighth Air Force. Insurance is about managing probability. So is shooting down German fighters. We cannot predict what any individual German pilot will do. But we can predict with mathematical certainty what German pilots in aggregate will do. They follow patterns.

They approach from specific angles because those angles offer the best combination of firepower and survivability. They attack at specific speeds because physics dictates those speeds. They break away in specific directions because aerodynamics demands it.

If we map these patterns statistically, we can predict not where a specific fighter will be, but where any fighter is most likely to be. We don’t need to shoot down specific aircraft. We need to fill zones of maximum probability with bullets and let statistics do the killing. The room erupted. Colonel William Hall, a West Point graduate teaching marksmanship since 1928, stood up in rage. This is absurd.

You’re asking us to abandon everything we know about gunnery. You’re telling our boys to close their eyes and spray bullets like they’re watering a garden. It’s not just wrong, it’s cowardly. But General Ekker had lost too many bombers to ignore any possibility. He authorized a limited test. For 6 weeks in October and November 1943, technicians at Eglundfield, Florida, fired millions of rounds at radiocrolled target drones over the Gulf of Mexico.

mapping probability distributions of successful hits under different firing patterns. They tested traditional aimed fire, gunners carefully tracking individual targets through sights. They tested barrage fire, gunners filling predetermined zones with bullets. They tested distributed fire, multiple gunners coordinating to create overlapping zones of coverage.

The results delivered to 8th Air Force headquarters November 28th, 1943 were stunning and undeniable. Traditional aimed fire achieved a hit rate of 0.5%. One hit for every 200 rounds fired. Zone fire achieved a hit rate of 4.2%. One hit for every 24 rounds fired. Eight times more effective than traditional marksmanship. The implications staggered everyone.

Colonel Curtis Lame, commanding the 3005th Bomb Group, future architect of the strategic bombing campaign against Japan, immediately grasped what this meant. Lame had no romantic attachment to traditional military methods. On December 8th, 1943, exactly 2 years after Pearl Harbor, he issued radical new doctrine to his gunners at Chelston Air Base.

Forget everything you learned in gunnery school. When a fighter approaches, don’t aim at him. Don’t try tracking him through your sights. Don’t calculate deflection. Aim at the space in front of your bomber where he has to fly to shoot at you. Fill that space with bullets. Create a wall of lead he has to fly through.

Make him commit suicide on your bullet stream. The new technique was officially christened zone firing or barrage fire. Though the gunners had earthier names, spray and prey, the garden hose method, or most commonly filling the bucket. The concept required completely reconceptualizing the gunner’s role. Instead of thinking of themselves as marksmen, aerial snipers picking off individual targets, they were to think of themselves as human machine guns, probability weapons, statistical instruments of death.

The emphasis shifted entirely from accuracy to rate of fire, from precision to saturation, from quality to quantity. Second Lieutenant Arthur Goldman, a bombardier with the 381st Bomb Group who manned nose guns when not on bombing runs, described the psychological difficulty in a letter to his wife that pass sensors.

Everything in your training, everything in your being tells you to aim at the enemy fighter. You see him coming, growing larger by the second, wings sparkling with cannon fire. You want to track him, lead him, shoot him down specifically. Your brain screams at you to aim, but we’re being told to ignore him completely and shoot at empty air where he isn’t yet, but might be. It feels insane, like closing your eyes and giving up.

But the mathematics say it works. So, we’re trying to retrain our instincts. The training transformation began immediately at six flexible gunnery schools scattered across America. Las Vegas Army Airfield in Nevada, Buckingham and Tindle in Florida, Harlingan in Texas, Fort Meyers in Florida, and Kingman in Arizona.

Since early 1942, these schools had been turnurning out thousands of aerial gunners monthly, teaching traditional marksmanship adapted for aerial combat. Now, almost overnight, the entire curriculum had to be revolutionized. Instructors who’d spent careers teaching careful aim were told to abandon everything they believed and teach statistical probability instead.

Master Sergeant Frank Rodriguez, a gunnery instructor at Las Vegas Army Airfield, remembered the chaos. We had kids and they were kids 18, 19 years old who’d been training for weeks learning traditional marksmanship. We taught them breath control, sight picture, trigger squeeze, all the fundamentals going back to the Revolutionary War. Then overnight, we’re telling them to forget all that and spray bullets at empty air. Some thought we’d gone crazy.

Hell, some of us instructors thought we’d gone crazy, too. The curriculum transformation was comprehensive and radical. Out went traditional emphasis on sight pictures and trigger squeeze that had defined military marksmanship for centuries. Outwent careful tracking of individual targets. Out went patient waiting for the perfect shot.

In came courses on probability theory that would have been more at home in a university mathematics department. In came studies of German fighter approach patterns based on analysis of thousands of combat encounters. In came training on rate of fire maximization, how to keep guns firing continuously without jamming from overheating.

The Waller gunnery trainer, a sophisticated electromechanical simulator projecting films of attacking fighters onto screens while gunners fired electronic guns, was completely reprogrammed. Previously, it rewarded accurate tracking of individual targets, giving highest scores to gunners who kept sights precisely on enemy aircraft.

Now, it was modified to reward volume of fire in specific zones, regardless of whether an enemy fighter actually occupied that zone at that moment. Gunners who filled assigned zones with highest bullet density scored highest even if they never tracked a single target. The most counterintuitive aspect was position firing developed at the Central Flexible Gunnery Instructor’s School at Fort Meers, Florida.

This technique, which would have seemed like madness to any traditional marksman, recognized a fundamental truth about firing from a moving platform. The bomber’s forward motion actually pushed bullets ahead of where the gun was aimed. This effect increased with angle of deflection.

If a wastist gunner fired directly at a fighter attacking from three Rs, directly perpendicular to the bomber’s path, the bullets would actually travel significantly forward of where the gun was pointing due to the bomber’s velocity of 180 to 250 mat. The solution was so bizarre, many gunners initially refused to believe it could work. Aim behind the attacking fighter, sometimes by as much as 30 or 40 degrees.

If a fighter attacked from three, the gunner should aim at four B’s or even 5Ds. Let the bombers forward motion carry bullets into the fighter’s path. Trust physics instead of instinct. Staff Sergeant Leonard Morrison of the 95th Bomb Group based at Horham in Suffuk, England, described his first successful use of position firing November 26th, 1943 during a mission over Bremen.

This 109 came in from three-hour level. Everything in my training, every instinct in my body told me to lead him, to aim ahead like with a duck hunter’s shotgun. Instead, following the new doctrine, I aimed behind him, way behind him, almost at our own tail. It felt completely wrong, like I was deliberately missing. I held the trigger down and watched my tracers curve forward through the air due to our plane’s forward motion.

The 109 flew right into them. The pilot probably never knew what hit him. His plane just came apart in the air. The mathematical foundation was codified in the November 1943 handbook. Get that fighter classified restricted. Distributed only to gunnery instructors and intelligence officers. This remarkable document just 47 pages long would revolutionize aerial combat.

Unlike traditional military manuals filled with precise procedures and rigid rules, get that fighter read more like a physics textbook, complete with equations, probability tables, and statistical distributions. The introduction stated bluntly, “This book deals only with the shot when he is actually coming in at you.

” Past experience has shown 90% of fighter attacks develop into this type of shot. Believe it or not, when a fighter is making his attack, you don’t aim ahead as in other shots. Always aim between him and the tail of your own plane because the forward speed of your plane is added to the speed of your bullet. The amount you aim behind is deflection.

The handbook included detailed probability tables showing exactly where gunners should concentrate fire based on angle of fighter approach. For a fighter attacking from 12 Z high, the favored German head-on attack, gunners should create a cone of fire 15 degree wide and 10 degree tall, centered on a point 50 yard in front of the bomber’s nose.

Every gun that could bear on this zone should fire continuously into it, regardless of whether a fighter was visible there. The mathematics predicted a fighter attacking from this angle would have to fly through this zone. If the zone was filled with sufficient bullet density, the fighter would be hit. For beam attacks from three ass or nineclaw, the zone shifted dramatically.

Gunners should aim 30 to 40° behind the fighter’s apparent position, creating a wall of bullets the fighter would fly into as the bomber’s forward motion carried rounds ahead. The manual included detailed diagrams showing these zones from every possible angle, turning aerial gunnery from an art into a science.

The impact on German fighter tactics was immediate and profound. By December 1943, Luftvafa pilots were reporting dramatic changes in American defensive fire patterns. Major Gunther Raal, one of the Luftvafa’s top aces with 275 eventual victories, noted the change in a tactical report dated December 15th, 1943.

The Americans have abandoned aimed fire for area saturation. Individual bombers no longer track us with their guns. Instead, they create zones of fire we must fly through to attack. Our standard attack approaches are becoming untenable. We are losing experienced pilots to what appears to be random fire, but is actually carefully calculated probability zones. The Germans were forced to adapt rapidly.

The favored head-on attack, devastating against American formations in early 1943, became increasingly costly. Approaching from 12 gau high meant flying directly into zones of maximum bullet density. Herman Friedrich Yopian flying with Yagtk 27 described the new reality in his diary. You can no longer duel with American bombers as we did in the past. Before it was a contest of skill, their gunners against our flying.

We could outmaneuver their aimed fire, dodge their tracers, slip through gaps in their coverage. Now it’s like flying into rain. The bullets are simply everywhere. There is no skill in avoiding rain. Lieutenant General Adolf Gallant, one of Germany’s most successful fighter leaders, would later write in his memoirs.

By winter 1943, the Americans had discovered something we Germans. With our emphasis on individual skill and precision had missed entirely in modern aerial combat at these speeds and altitudes, statistical probability beats individual marksmanship every time. They turn their gunners into probability weapons. And we couldn’t counter it with skill alone.

The transformation of American gunnery training accelerated through winter 1943 to 44. By December, the six flexible gunnery schools were graduating 3,500 gunners every single week, all trained in new zone firing techniques. The standardization was remarkable.

A gunner trained at Kingman in the Arizona desert would use exactly the same techniques as one trained at Tindle on the Florida coast. The curriculum had been reduced from 12 weeks to six with fully two weeks devoted entirely to understanding probability zones and position firing techniques. Traditional marksmanship training had been reduced to just 3 days, barely enough time to familiarize gunners with their weapons basic operation. The human dimension of this transformation was profound.

Young Americans who’d grown up during the depression. Many from rural backgrounds where hunting was part of life. Where a man’s ability with a rifle measured his worth were being told to abandon everything they believed about shooting. They were being asked to fire at empty air while German fighters bore down on them with cannons blazing, to trust mathematics over instinct, probability over skill, statistics over courage.

Staff Sergeant William Patterson of the 379th Bomb Group captured this psychological struggle in a letter home. They want us to be machines, not marksmen. We’re supposed to fill zones with bullets according to mathematical tables, not shoot at actual targets. It goes against everything I learned growing up in Montana.

Everything my father taught me about hunting. Everything that feels right. But the math works. More bombers are coming home. So, we close our eyes to what we see and trust what the slide rules tell us. The effectiveness of the new tactics became undeniable during big week, February 20th 25, 1944, when the eighth air force launched Operation Argument, its most intensive bombing campaign to date.

Over 6 days, American bombers flew 3,300 sorties against German aircraft factories in what would be remembered as one of the decisive air battles of the war. The bombers faced the full strength of the Luftvafa fighter force with the Germans committing every available fighter to defend these critical targets. Despite facing intense opposition, bomber losses were significantly lower than during the catastrophic October 1943 raids.

More importantly, German fighter losses were catastrophic. The Luftvafa lost over 350 aircraft with 100 experienced pilots killed and another 150 wounded or captured. Many of these losses came from bomber defensive fire as German pilots discovered their traditional attack patterns had become suicidal.

Technical Sergeant Raymond Johnson, a tail gunner with the 447th Bomb Group, shot down three fighters during big week without once specifically aiming at any of them. His afteraction report read, “I just kept filling my assigned zone with lead whenever fighters appeared. I never tracked a single target, never put my sight on a specific aircraft. I just kept the triggers down and filled my zone.

The fighters flew into it like moths into a flame. The psychological impact on gunners was complex and often troubling. Many felt disconnected from their successes, as if they hadn’t really earned their victories. Staff Sergeant Paul Williams of the 96th Bomb Group wrote home in March 1944. I shot down a faka wolf yesterday, but I don’t feel like I did it.

I was just hosing bullets into empty air where the mathematics said to shoot. And he happened to fly into them. There’s no satisfaction in it. No sense of skill or accomplishment. We’re not warriors anymore. We’re probability machines. By March 1944, the operational research section had analyzed over 10,000 individual combat encounters between American bombers and German fighters.

The data was overwhelming and undeniable. Bombers whose gunners used zone firing techniques were 3.7 times more likely to destroy attacking fighters and 2.1 times more likely to survive their missions than those still using traditional aimed fire. Perhaps most surprisingly, average ammunition expenditure per confirmed kill had actually decreased from 12,600 rounds to 7,800 rounds as gunners were filling high probability zones rather than chasing targets across the sky with long ineffective bursts.

The German response reveals just how effective the American transformation had become. A captured Luftwafa document from March 1944, Tactical Directive 447, explicitly warned pilots, “The American bombers no longer engage in aimed defensive fire as they did previously. They create zones of impenetrable bullet density at calculated points around their formations. Standard attack protocols must be abandoned.

Pilots should seek isolated aircraft separated from formations or attack from angles outside the predicted zones. The evolution of American gunnery continued through 1944 with the introduction of computing gun sites. The K13 developed by Sperry Corporation and similar models from other manufacturers were primitive analog computers that could automatically calculate necessary deflection based on range and relative motion.

These devices, technological marvels for their time, took the mathematical burden off the gunner entirely. Technical Sergeant Michael Palowski, using a K13 computing site in a B7’s tail position, described the experience in a letter that survived in his family’s possession. It’s eerie and unnatural. You put the fighter in the crosshairs of your sight, but the gun fires somewhere else entirely where the computer calculates the bullets need to go. The site is doing math. I couldn’t do with pencil and paper in an hour. And it’s doing it continuously, adjusting

for our speed, his speed, altitude, temperature, everything. You’re not shooting anymore. You’re designating targets for a machine that does the shooting. The apotheiois of statistical gunnery came with the B29 Superfortress and its revolutionary central fire control system. This system developed by General Electric at a cost exceeding a hundred million dollars, more than $1.

5 billion in today’s money, took zone firing to its logical conclusion. Instead of individual gunners controlling individual guns, a central computer calculated firing solutions for all guns simultaneously, creating mathematically optimized zones of fire around the aircraft.

The system was so sophisticated it could track multiple targets simultaneously, calculate their probable attack paths, and preposition guns to fill those zones before the fighters even began their attack runs. Gunners became sensor operators, merely designating targets for mathematical engagement by the computer.

It was the ultimate expression of statistical gunnery, human judgment replaced almost entirely by calculated probability. Major Robert Sterling, who transitioned from B17s to B29s in late 1944, was amazed by the transformation. In the B7, we manually created zones of fire based on training and instinct. In the B29, a computer does it automatically.

It calculates wind speed, temperature, humidity, our speed, target speed, even the Earth’s rotation. It’s not shooting anymore. It’s applied mathematics. We’ve industrialized death itself. The impact extended far beyond mere tactics. The transformation of aerial gunnery represented a fundamental shift in military thinking from individual skill to statistical probability, from craftsmanship to industrial process, from art to science.

It prefigured the computerized warfare of later decades, where human intuition would increasingly yield to mathematical calculation, where algorithms would replace instinct. The Luftvafa’s adaptation to American statistical gunnery drove further tactical evolution. By summer 1944, German fighters had largely abandoned close-in attacks on bomber formations, preferring to launch rockets from beyond effective gun range or attack stragglers separated from defensive formation.

This forced another American innovation, reconnaissance by fire, where gunners would spray bullets into empty zones where fighters might be lurking undetected, using ammunition to probe for threats that might not even exist. The culmination of the statistical gunnery revolution came during the massive bombing raids of early 1945.

On March the 2nd, during a thousand bomber raid on Dresden, masked formations faced one of the last major Luftvafa defensive efforts of the war. Using fully developed zone firing techniques, computing gun sites, and coordinated defensive patterns, the bombers claimed 67 German fighters destroyed. Postwar analysis of Luftvafa records confirmed 41 actual kills, a claiming accuracy of 61% compared to less than 10% in 1943.

The revolution was complete. The effectiveness of zone firing wasn’t limited to American heavy bombers. Medium bombers like the B-26 Marauder and B-25 Mitchell adopted similar techniques with devastating effect. The US Navy incorporated zone firing into training for torpedo bomber gunners.

Even fighter pilots began using statistical principles for deflection shooting. Though application was necessarily limited by their forward firing armament, the international impact was significant. The Royal Air Force, initially deeply skeptical of American spray and prey tactics that seem to violate every principle of British gunnery tradition, began incorporating zone firing into Lancaster and Halifax bomber training in early 1944.

Soviet aviation, receiving technical information through lend lease exchanges, adopted modified versions of American statistical gunnery for their IL2 Sturmovic ground attack aircraft and PE2 medium bombers. Wing Commander Douglas batter, the legendary legless RAF Ace, observed the American approach during a liaison visit in March 1944.

It offends every principle of marksmanship we hold dear. It violates everything we’ve taught since the Longbow. But the Americans have proven that in modern aerial combat at these speeds and altitudes, mathematics trumps tradition. They’ve turned gunnery from an art into a science. And the science works.

The psychological impact on German pilots was profound and demoralizing. Interviews with captured Luftvafa pilots in 1944 and 1945 reveal a consistent theme. American defensive fire had become psychologically overwhelming. It wasn’t the accuracy that broke their morale, but the sheer density, the impossibility of finding a safe path through the statistical storm.

Fran Stiggler, the veteran Luftvafa pilot who’d famously escorted a damaged B7 to safety in December 1943 in one of the war’s most remarkable acts of chivalry. Later reflected on the changing nature of combat. In 1943, you could still fight American bombers with skill and courage. By 1944, skill meant nothing.

Their defensive fire had become so dense, so mathematically distributed that attacking them was pure chance. You weren’t fighting gunners anymore. You were fighting probability itself. Every attack became Russian roulette. The legacy of the zone firing revolution extended far beyond World War II, influencing military technology and doctrine for decades to come.

The principle of statistical engagement became fundamental to modern air defense systems. The failank close-in weapon system CIWS used on naval vessels today operates on the same basic principle developed by those B7 gunners, creating walls of bullets in the predicted path of incoming threats.

Rather than trying to achieve precise hits on specific targets, modern missile defense systems like Patriot and THAAD calculate probability intercept zones rather than attempting precise one-on-one interceptions. The Israeli Iron Dome system creates statistical interdiction zones to protect against rocket attacks. Every radar directed gun system creates optimal burst patterns.

Every defensive system based on probability rather than precision traces its conceptual ancestry to those American bomber gunners who learned to stop aiming and start trusting mathematics. Dr. Robert McNamera who served as a statistical analyst with the eighth air force before becoming secretary of defense in the 1960s reflected on the significance of this transformation in a 1962 interview.

The zone firing revolution of 1943 to44 was the first practical application of operations research to combat. We proved that statistical analysis could be more effective than individual skill. It was the beginning of systems analysis in warfare, the start of the mathematical approach to military problems that would eventually lead to computerc controlled combat systems.

The human dimension of this transformation shouldn’t be overlooked or minimized. Thousands of young Americans raised on stories of frontier marksmen like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, taught from childhood that a man’s skill with a firearm was a measure of his worth, had to abandon these deeply held beliefs and trust in mathematical abstractions they barely understood.

They had to fire at empty air while German fighters bore down on them with cannons blazing, believing that probability would protect them better than their own aimed fire. Staff Sergeant William Crawford of the 379th Bomb Group, who flew 35 missions as a waste gunner, reflected years later in an oral history interview. We went from being gunners to being probability implementers.

It was hard to accept at first, shooting at nothing while Messor Schmidt were coming straight at us with their wings lit up by cannon fire. Every instinct screamed at us to aim at them, to track them, to shoot them down specifically. But the math worked. More of us came home because we trusted the statistics instead of our instincts.

The training infrastructure reveals the massive scale of this transformation. Between December 1941 and August 1945, the Army Air Forces trained approximately 176,000 flexible gunners along with tens of thousands more in other gunnery positions. By war’s end, virtually all bomber gunners had been trained in zone firing techniques.

The early war emphasis on traditional marksmanship, breath control, sight picture, and trigger squeeze had been completely replaced by training in probability zones, position firing, and rate of fire maximization. The material impact was equally staggering. American industry produced over 1.5 billion rounds of 50 caliber ammunition during the war. Much of it expended in zone firing over Europe and the Pacific.

The average B7 carried 11,000 rounds on a typical mission. During major raids involving hundreds of bombers, American gunners could put over 20 million bullets into the air in a single day. It was industrial warfare at its most literal. The mass production of probability delivered at 2,800 ft per second. The Pacific theater provided final validation of statistical gunnery.

B29 superfortresses attacking Japan faced a different challenge than B17s over Germany. Japanese fighters, generally lighter and more maneuverable than their German counterparts, use different attack techniques. Yet, zone firing principles proved equally effective.

The centralized fire control system of the B29 combined with radar directed guns created probability zones Japanese pilots found impossible to penetrate. Major Saburo Sakai, Japan’s leading surviving ace with 64 confirmed victories, described attacking B29s in early 1945. It was like flying into a mathematical equation. The Americans hadn’t just mechanized aerial gunnery. They’d reduced it to pure mathematics.

They calculated every possible approach angle and filled it with bullets. There was no path through based on skill or courage. Only luck could get you past their statistics. We weren’t fighting men anymore. We were fighting probability itself. The final statistics tell the story of transformation.

In August 1943, before the adoption of zone firing, the eighth air force was losing bombers at an unsustainable rate. Over 10% permission during the Schwvine Fort Regensburg raids with some groups suffering 50% losses. Gunners were claiming hundreds of German fighters destroyed, but actually shooting down fewer than one in 10 of their claims.

By spring 1945, using fully developed statistical gunnery techniques, loss rates had dropped to under 1% per mission. Despite continued German opposition, American gunners who’d been achieving hit rates of 0.5% in 1943 were achieving rates approaching 5% by 1945. a 10-fold improvement based entirely on abandoning traditional marksmanship for statistical engagement.

The transformation was complete and irreversible. American gunners had stopped firing at what they could see and started firing at what probability predicted. They’d abandoned the romance of marksmanship for the reality of mathematics. They discovered that in modern aerial warfare at jet age speeds, statistics beat skill, probability beat precision, mathematics beat marksmanship. They’d learned to stop aiming and trust the zones.

To cease tracking and trust the calculations, to abandon everything they believed about combat and trust the numbers. The boys who’d gone to war in 1942, believing in the power of a well- aimed shot, came home in 1945 understanding that modern combat was ruled by statistical inevitability.

They’d traded their identities as warriors for roles as probability implementers. They’d exchanged the satisfaction of individual victory for the effectiveness of mathematical certainty. And in that transformation, they’d helped win the air war over Europe, proving that sometimes the most counterintuitive solution is the most effective.

That abandoning everything you believe about combat might be the key to victory. And that in the age of industrial warfare, mathematics had become the deadliest weapon of all. These young Americans had participated in one of the most profound military transformations in history.

A revolution that would echo through the decades in every computer controlled weapons system, every automated defense network, every algorithm-driven military technology. They’d proven that in the modern age, victory belonged not to the best marksmen, but to those who best understood and applied the cold, impartial equations of probability.

They’d turned warfare from an art into a science, from a contest of individual skills into a problem of statistical optimization. And in doing so, they hadn’t just won a war, but transformed the very nature of combat itself, ushering in an age where mathematics would increasingly determine the outcome of battles, where computers would replace human judgment, and where statistical probability would become the ultimate arbiter of life and death in the skies above the battlefield. healed.