She didn’t cry when they tied the noose. He didn’t flinch when he stepped forward. One was called savage. The other had buried his wife in silence. But that day, in front of the whole town, fate rewrote them both. The first thing they heard was the wind. Not the breeze that tumbled through the canyons most mornings.

Not the dry rustle that sometimes teased the edges of canvas tents, but a sharp violent wind that slammed against the wooden walls of the courthouse like it was trying to interrupt the sentence being read. It rattled loose shutters, flung dust across the square, and sent every hat brim flapping, but no one moved.

Not the judge, not the town’s folk gathered like crows around a carcass, and certainly not the woman standing with her hands bound behind her back, chin lifted, eyes like fire trapped in glass. Her name was Anakah, just Anakah. No surname she’d admit to, no father anyone knew.

Her mother had been Apache, barely tolerated on the edge of town, then entirely unwelcome once Anakah was born lighterkinned and sharper tonged. She’d grown like a thistle, rough and untamed, learning to ride before she could spell, trapped before she could read, and survive when others would have curled up and died. The town never forgave her for it.

They said she stole a horse and a knife and food from Widow Maple’s shelf. They said she lured young men into the woods with wild promises and Apache blood magic. They said she once cut a man’s throat with nothing but a hairpin. But they never proved any of it.

Only this time, someone found her in the reverend’s barn with a bloodied rag and a half- deadad mule, and that was enough. Accusation turned to conviction in a single day. By morning, the gallows had been built. Anakah stood there now, boots caked in dust, hair matted from days in a cell. She didn’t beg. She didn’t curse.

She just looked out at them all, eyes moving from face to face like she was memorizing who had shown up to watch her die. Some of them flinched under that gaze. Most didn’t. The preacher was already sweating through his collar as he opened the Bible, voice trembling more from fear than reverence. “Let justice be done though the heavens fall,” he recited.

The executioner, an old man named Cobb, whose hands shook more than the leaves in a storm, reached for the rope. And that’s when the child cried out. It wasn’t loud, just a soft, confused sound, a boy’s voice high and uncertain. The crowd turned, not toward the gallows, but toward the dusty road that cut through the center of town.

And there he was, a little boy, no more than five, blonde hair sticking up like he’d just woken from a nightmare. One boot on, one off. And behind him, walking with the slow certainty of someone who’d fought through storms worse than this, came the rancher, Ruben Ka. Most folks had forgotten what his voice sounded like.

He didn’t come into town unless it was Sunday or an emergency, and ever since his wife passed in childbirth, he’d kept mostly to himself. 40 acres west of town, one son, one horse, one Bible with pages torn from too much reading. That was Ruben Cain. He didn’t say a word as he approached the gallows. The crowd parted, but not out of respect, out of confusion. He was still wearing his work coat, dust clinging to his shoulders, sweat along his collar.

The boy, Tommy, clutched a stuffed rabbit in one hand, the other gripping his father’s fingers. Judge Harrow cleared his throat. Reuben, this ain’t your business. Reuben looked up, eyes fixed not on the judge, but on Anakah, and for a moment something passed between them. She didn’t look confused, just tired. Her jaw didn’t loosen, but her eyes blinked once, slow, heavy, as if she’d seen something unexpected and didn’t know if it was mercy or another cruel twist of fate.

“My son needs a mother,” Reuben said simply. The silence that followed was deeper than any prayer. Even the wind quieted. The judge scoffed. “You can’t be serious. She’s I didn’t ask if I could be,” Reuben said, stepping forward. “I’m offering to take her in, not as a servant, not as a prisoner, as a wife.

” Gasps rippled through the crowd like someone had tossed a match into dry hay. “You can’t,” the preacher began. “I can.” Reuben’s voice didn’t rise. It didn’t need to. You want to hang her? Go ahead. But my boy already lost one mother. He cries for her every night. And today, for the first time in months, he asked if we could ride into town. I didn’t ask why. Now I know.

Anakah’s lips parted slightly, but still she said nothing. The judge turned to the executioner. This ain’t legal. She was tried. “She ain’t dead yet,” Reuben said. and the Lord gives second chances. If you won’t, I will. The preacher faltered, fingers trembling on the pages of the good book. Reuben, this is a dangerous woman. She’s breathing, Reuben replied. And breathing ain’t a crime.

It wasn’t a poetic argument. It wasn’t the kind that one courtroom dramas, but it wasn’t meant to be. It was meant to hold weight, and somehow it did. The judge stepped back, shaking his head. You’ll be responsible for her entirely. Whatever she does, whatever happens, it falls on you. Reuben didn’t blink.

It already does. And with that, he walked to the gallows, cut the rope himself, lifted Anakah down like she weighed no more than a sack of oats. She didn’t resist, didn’t speak, didn’t cry. She just stood beside him as he nodded to Tommy and turned back down the road they’d come. No one spoke as they left.

Only when they were out of sight did the murmurss begin again, quiet at first, then louder like a tide returning after the moon’s silence. Some called him a fool. Others whispered about curses and savagery and blood, but none followed, and that for now was enough. Back at the ranch, the sky burned orange. Chickens scattered as hooves clopped up the path.

Reuben dismounted first, lifting Tommy down, then turned to Anakah. She hesitated at the edge of the porch, hands still raw from rope burn, eyes flicking toward the hills beyond like she could still run. But something stopped her. Maybe it was the boy. Maybe it was the silence.

Or maybe it was the fact that for the first time in her life, someone had stepped forward instead of away. Inside the air smelled of bread and smoke and old wood. Reuben motioned toward the basin. Wash up. Supper’s simple. Won’t apologize. Anakah nodded once. No thank you. No words at all. Just a flicker of something behind her eyes as she stepped into the cabin.

Tommy watched her closely, not afraid, not sure, just watching. And so the night began. But this story didn’t end with a rescue. It started with one. She didn’t sleep that night. Not really. She closed her eyes, curled on the far edge of the strawsted mattress Reuben had dragged from the barn to the front room, but her breath never settled. Her muscles remained tight like a horse tethered too short for too long.

The walls creaked as the wind died down, and from the loft above, the soft rise and fall of a child’s breathing pulsed like a drum beat. Familiar, fragile, hopeful, it terrified her. Reuben hadn’t spoken again after supper. He’d cleaned his plate, fed the fire, then disappeared into the other room with his son, and shut the door behind them.

Anakah had sat at the table long after the plates had cooled, her back straight, her eyes fixed on the flickering shadows thrown by the hearth. She hadn’t asked what came next, and he hadn’t told her. She was used to that. Most men had two tones: command or silence. Ruben Caine was all silence, but not the cruel kind. Not the sort that lingered to punish.

No, his silence felt deliberate, almost sacred, like he didn’t want to say what couldn’t be unsaid. That made him dangerous in a different way because she couldn’t read him, and unreadable men were never safe. At dawn, she stirred, stretching slowly and glancing toward the front window. The sky beyond the glass was the color of bruised peaches.

Low clouds caught like breath between the hills. She wrapped the blanket tighter and crept toward the door. It wasn’t locked. That surprised her. She stepped out onto the porch barefoot. The wood was cool and damp beneath her heels, and the quiet felt thick, like a blanket thrown over the world.

Her eyes drifted toward the barn, then the tree line beyond. If she ran now, she might make it. The rope burns on her wrist still stung, but her legs worked fine. Her lungs, too. She heard the chickens rustle first, then the metallic clink of a water bucket. She turned. Reuben stood by the well, drawing water with practiced efficiency. He didn’t look up when he spoke.

“If you’re going to run, best head north. The rivers swelled after last week’s rain. Town won’t come looking for you that way.” Anakah didn’t answer. He finally turned, lifting the bucket with one hand, nodding once toward the porch. “You thirsty or not?” She stepped down slowly. The cold bit through the soles of her feet, but she didn’t flinch.

As she reached for the ladle, Reuben’s eyes flicked to her wrists. “I got salve inside,” he said. “Used it when my boy scraped up bad last spring. Should help.” I don’t need your salve, she muttered. Didn’t say you did, he replied evenly. They stood like that for a beat, her drinking intense gulps, him watching her like he was waiting to see if she’d vanish into smoke.

Then Tommy’s voice broke the standoff. “Pa,” the boy called sleepily from the porch. He stood there barefoot, one eye half shut, rabbit clutched in one arm. Reuben didn’t turn. Inside, son. I’ll be right there. Tommy’s gaze landed on Anakah. He didn’t speak, just stared. She stared back. That moment hung heavy.

Then the boy nodded like he just decided something and disappeared inside. Anakah set the ladle down. You didn’t lock the door. Nope. Why? Reuben wiped his hands on a cloth. You strike me as the kind who doesn’t need a locked door to leave. And if I did, he paused, looking her full in the face for the first time, then I reckon I’d already be chasing you.

She didn’t like that, not because it scared her, but because it didn’t. After breakfast, quiet, plain, and eaten without much conversation, Reuben handed her a pair of gloves and pointed to the wood pile. Storm knocked a few branches down. Need clearing before the cows start wandering past the fence. She hesitated.

You want me to chop. I want you to do something. Don’t care what. That somehow felt worse than a command. Still, she worked. She always had. By midday, her shoulders achd from swinging the axe, but it was a good ache, the kind that silenced the thoughts. Reuben checked on her once, nodded, and returned to the barn.

He was a man of few words and fewer opinions, or maybe just not one to offer them until necessary. Tommy stayed close all day, trailing behind her like a shadow with questions. “Do you know how to ride fast?” he asked. “Yes, faster than P.” “I haven’t seen him ride.” “Have you seen a bear?” “Yes.” What did you do? Watched it. Didn’t blink. He seemed satisfied with that.

Later, he brought her a tin of beans and sat beside her as she ate, swinging his legs off the porch. “Are you going to stay?” he asked finally. Anakah didn’t answer. That night, she cleaned herself properly. Reuben had boiled water for the basin, left it near the hearth without comment. She scrubbed away the sweat, the dirt, the smell of prison.

When she looked in the cracked mirror above the mantle, she saw the bruises under her eyes, the tightness in her jaw, and the scars that danced across her collar bone. She barely recognized the woman staring back. Reuben appeared in the doorway as she pulled on a clean shirt. “One of his late wife,” she guessed, judging by the stitching. “You work hard,” he said simply. She turned. Do you expect thanks? No, he said just noticing.

She almost asked why he did it, why he stepped in when no one else had, but she didn’t. She wasn’t ready to owe him a second thing. Later that week, a rider came. Anakah spotted him first, just a speck of movement on the trail, but her pulse quickened all the same. She dropped the pale she’d been carrying and stroed toward the porch.

Reuben stepped out of the barn before the rider even reached the gate. The man was dressed like Law, but rode like a bounty hunter, fast, loose, and already sweating. He didn’t dismount. Cain, the writer, called. Reuben didn’t answer. Judge wants confirmation. She’s still breathing. Town’s uneasy. Folks are saying you’ve gone soft.

Anakah stood silently by the fence, arms crossed. You seen her? Reuben said flatly. Ride back. Tell the judge. The writer squinted toward Anakah. She yours now. Reuben nodded once. Paperwork s in the courthouse. And if she runs, she won’t. The man laughed. That right savage. Anakah didn’t flinch. She stepped forward slowly until the man could see the coiled tension in her shoulders, the steel in her eyes.

I don’t run, she said. I bury. Reuben didn’t move, didn’t blink, just watched. The writer smirked, spat in the dirt, and turned his horse. They didn’t speak much after that, but something shifted. That night, Reuben brought out a box. Inside were letters, faded, water stained, written in a woman’s hand.

“My wife wrote these,” he said, placing them gently on the table. every Sunday before before the fever. Anakah looked at them. Why are you showing me this? Because I don’t want ghosts in my house, he said. Only people. If you’re going to stay, be real. Don’t hide behind what they said about you. She didn’t read the letters.

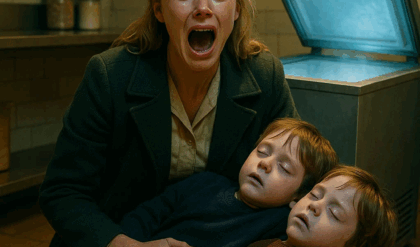

Not that night. But she kept them close. The days turned into weeks. Anakah men minded a fence, cooked a stew, wrapped Tommy sprained ankle when he fell chasing chickens. She didn’t smile much, but her shoulders relaxed. Her voice lost its edge. Her steps grew slower, not from exhaustion, but from presence until the scream.

It tore through the trees like a bullet, sharp and sudden. Anakah dropped the wash bin and ran. She found Tommy near the creek, blood on his sleeve. two boys from town standing over him with sticks. One held a rock, the other was laughing. “You ain’t got no real mama,” the older boy sneered. “Just a savage who should have swung.

” Tommy was crying, holding his arm. Anakah didn’t stop to think. She moved like lightning, grabbed the nearest boy by the collar, and flung him backward. The second one yelped and bolted. The first scrambled to his feet, face pale. You touch him again,” Anakah hissed. “And you’ll learn what savage really means.” The boy ran.

She dropped to her knees beside Tommy, cradling him gently. “Let me see,” she whispered. His arm was scraped, not broken, but the wound wasn’t the problem. He looked up at her, eyes wide with something too old for his age. “Is it true?” he asked. “Are you savage?” She didn’t answer right away.

Then she touched his cheek, thumb brushing away a tear. Sometimes, she said, but only to people who deserve it. He didn’t look away, didn’t cry more. He just nodded. That night, she didn’t sleep on the spare mattress. She sat near the hearth. Tommy curled up beside her, head on her lap. Reuben stood in the doorway for a long time, watching them.

Then he crossed the room, sat down in the opposite chair, and poured her a cup of coffee. “Thanks,” he said quietly. For the first time, she smiled. “Just a little.” The following days moved like water down a dry creek, hesitant at first, then with quiet purpose. Anakah’s presence was no longer treated as disruption.

She’d become part of the rhythm, one motion in the larger motion of Reuben Cain’s homestead. Mornings began before dawn before the rooster dared try its voice. Reuben would move out into the fields with his tools slung across his shoulder, and Anakah would be up just behind him, checking on the hens, boiling water, brushing straw from Tommy’s hair when he shuffled sleepily into the kitchen.

It wasn’t spoken, but it was real. The way routines, when shared in silence and in necessity, slowly form something closer to kinship than words ever could. But peace doesn’t settle forever in a land carved by struggle, and their silence was being measured from afar, tallied by those who hadn’t forgotten the rope. Not everyone saw Reubin’s act as mercy.

Some took it as insult, others as weakness, and a few, those who’d clung longest to old power and older pride, took it as betrayal. It was Sheriff Mather, who brought the first formal warning. He rode out one evening as the sky blushed crimson behind the ridge, hat low over his brow, badge glinting even in dusk light.

Reuben was splitting logs by the barn. Anakah saw the horse first. She stepped onto the porch, her grip tightening on the broom she held. Mather rained in slow, expression unreadable. Even in, Reuben. Cain didn’t look up. Even in the sheriff dismounted, boots crunching soft against the dirt. Didn’t mean to intrude. Town espen restless.

Figured I ought to pass word along before things got ugly. Anakah stepped down from the porch. Her presence made Mather hesitate for half a second, but he didn’t flinch. “What kind of ugly?” Reuben asked, finally setting his ax down. “Folks don’t take kindly to what they think is law being undermined,” Mather said carefully. “You taking her in like that saved her from the gallows.

They see that as a message. Some think it invites trouble. Others think it demands justice.” Reuben wiped sweat from his brow. Justice already tried to swing her. And failed, Mather muttered, which some don’t like. Anakah moved beside Reuben. Then she didn’t speak. Just stood there, arms crossed, chin raised.

Not defiant, not threatening, just present. Mather shifted uncomfortably. I ain’t here to threaten, but there’s whispers. Group of men been meeting out near the old saloon ruins. late, whispering names that don’t belong to them. Reuben’s jaw flexed. You telling me to run? No, the sheriff said, just telling you to be ready.

He mounted again, pausing only to glance once more at Anakah. This land remembers blood, ma’am. Sometimes more than it should. He tipped his hat, rode off without another word. Reuben stood in the settling dust for a long while, then turned to Anakah. “You scared?” he asked. “No,” she replied flatly. He nodded once, didn’t think so. But that night, Reuben didn’t sleep easy.

He sat by the window long after the others had gone to bed, rifle resting across his knees, fire light dancing in his eyes. Anakah watched him from the corner, curled on the mattress with Tommy nestled against her chest. She knew the type of fear that would name itself, the kind that settles in a man’s bones, not because he fears for himself, but for something he never expected to care about.

By morning, it was clear neither had slept. “Don’t let Tommy near the ridge today,” Reuben said over coffee. “And keep a rifle near the porch.” Anakah didn’t ask why. She just nodded. By noon, they knew why. It wasn’t a mob, not yet. Just three riders. Men Anakah recognized from the gallows. One had held the rope.

Another had called her beast to his daughter’s face. The third, grizzled and tight jawed, had once tried to buy her for a bottle of whiskey outside a trading post. They didn’t dismount when they approached the house. just sat their horses, rifles visible, voices oily with practiced menace.

“You don’t look much like a wife,” the first one called. “More like a mud in a dress.” Anakah stood at the top of the steps, rifle already cradled in her arms. She didn’t raise it. Not yet. But her eyes didn’t blink. She cooked for Ukain. The second one sneered. Or just bite. Reuben stepped onto the porch then, slow, deliberate, placing himself half a step in front of Anakah.

“You fellas got business?” he asked evenly. “Town’s just curious what you’re breathing out here,” said the third. “Ain’t exactly Christian, is it? Letting a heathen raise your boy.” “Careful,” Reuben said. “Your tone slipping.” The second man smirked. “We’re just talking, Reuben. seeing if you’ve lost your mind or just your manhood. Anakah’s finger grazed the trigger.

“You ride back to town,” Reuben said, voice a low growl. “Now tell them I ain’t hosting guests. And if you come again, don’t come with questions. Come ready.” “They didn’t laugh this time.” Something in Reubin’s eyes, steady, unblinking, cooled the smirks right off their faces. One by one, they turned their horses and rode out.

Not fast, but not slow either, like men aware of just how close they’d come to crossing a line. When they were gone, Reuben sighed and leaned the rifle against the porch rail. “You all right?” he asked. “I’ve had worse,” Anakah said. “Don’t mean you should keep having it.” They didn’t speak much after that, but later, after Tommy was asleep, Reuben poured two fingers of coffee into a tin mug and handed it to her. She took it without a word.

“You ever miss where you came from?” he asked softly. “I never had a wear,” she answered. “Just a series of ws.” He nodded. That was the first time he told her about his wife. Her name had been Clara. She de died in the winter. Fever came fast, burned her up quicker than snow could melt. Tommy hadn’t spoken for weeks after.

just clung to that rabbit like it held her voice inside it. I buried her near the birch, Ruben said. Didn’t mark it, thought about it, but it felt wrong somehow, like I was carving it in stone that she was gone. Anakah looked toward the trees. The birch stood out, silver bark against the darker trunks. “She’d like you,” Reuben added.

Anakah arched an eyebrow. “You sure?” He half smiled. She liked truth and you wear it like a blade. She didn’t know what to say to that. And so the quiet returned, but the storm was already rolling. Two nights later, Reuben rode into town. Supplies, he said, but Anakah knew better.

He wanted to look the judge in the eye, see what loss still meant, if anything, see if the rope was being measured again. He left her with two rifles and strict instruction not to open the door for anyone but him. Tommy cried when he left, held Reubin’s leg tight enough to bruise. Anakah peeled him off gently and carried him back inside. That night, thunder rolled in, not from the sky, but from hooves.

Six riders, lanterns lit, voices drunk and loud and cruel. They circled the house once, laughed, threw rocks, called her names that weren’t worth remembering. Tommy woke screaming. Anakah lit one lamp, sat in the rocking chair by the door, rifle on her lap, calm, ready. They didn’t try the door, but one voice lingered. Heard she sleeps with snakes.

Heard she eats M. Heard she made the boy kill his own rabbit. Anakah’s breath didn’t change, but she memorized each voice. Each laugh, each cowardly slur tossed into the night like a stone through stained glass. They left just before dawn. And when Reuben returned later that day, face tight, jaw locked, she told him everything.

He didn’t raise his voice, didn’t rage. He just sat and said, “You still want to stay?” She nodded. You could leave. They wouldn’t follow far. She shook her head. If I run now, I’ll be running forever. He poured them both coffee, took a sip, then said, “Good, because I’m done burying people.” That night, they slept close. Not together, not yet, but close enough to feel each other’s breath.

And outside, the wind changed. It carried a scent no one had smelled in months. Rain and reckoning. The rain came like a cleansing fire, not gentle, not warm, but hard and sharp, stripping the land down to mud and bone. It started just before dawn, a low patter that grew until it roared against the roof like a thousand tiny fists.

The kind of rain that drowns tracks and memories alike. Anakah woke to the sound, her first instinct to check the rifle, the second to check the child. Tommy was curled deep beneath his quilt, undisturbed by the storm. She stood at the window, watching the world vanish in sheets of water. And for the first time since stepping foot on cane land, she allowed her fingers to loosen at her sides.

The night had passed without another visit. No riders, no voices, no threats hissing through the dark like snakes, just rain. Reuben found her standing there when he came down the stairs. He paused a long moment, then stepped beside her, his voice low. They won’t ride in this. “No,” she murmured. “But they’ll talk while they wait.

” He nodded slowly. “Let M talk talking sfree. Action costs more.” Anakah didn’t smile, but there was something near the edge of one. Something not quite mockery, not quite warmth. Breakfast was quiet, but unhurried. Reuben made porridge, stirred it slow, let the oats thicken before scooping them into tin bowls.

Tommy added sugar from a jar he’d clearly been saving, and Anakah didn’t stop him. Let the boy have sweetness where he could. After the meal, Reuben pulled on his coat and nodded toward the barn. “She’ll leak if I don’t patch her now. Storm might last days.” “I’ll help,” Anakah said, already reaching for her boots. He didn’t argue, just handed her a second coat. Clara s again.

Out in the barn, the air was damp and rich with the scent of hay, earth, and old wood. They worked side by side in silence, climbing rafters, hammering patches, sealing weak beams with tar and prayer. Reuben worked like a man who trusted the woman beside him not to fall, not to flinch. Anakah noticed that, noticed everything.

They were finishing the final beam when he asked, “What did they call you before?” She looked down at him from the rafter. Before what? Before the gallows. Before me. She climbed down slowly, boot scraping wood. Depends who was speaking. Some said which, others said thief. My mother called me wolf. He blinked. Why? Because I watched, she said, and remembered and struck only when the time was right.

Reuben tied off a knot and stood back. She’s still alive. Anakah shook her head. Buried her in winter. Couldn’t dig deep enough. Coyotes got to her. He didn’t speak again, just nodded. They understood each other in that silence. By afternoon, the rain eased into a gentle hush. The kind of soft rhythm that lulled nerves tricked a person into feeling safe.

Reuben took Tommy fishing at the creek behind the hill. Anakah stayed behind, tending to the hearth, sewing buttons back onto Reuben’s shirts with steady, careful hands. She wasn’t trying to be someone else. She wasn’t trying to prove herself. She was simply doing what needed doing. When the boys returned, soaked and triumphant with three small trout, Reuben watched Anakah move through the kitchen, guiding Tommy’s hands as he cleaned the fish, showing him how not to waste the meat.

She’s kind, the boy whispered later that night as Reuben tucked him in. She is, Reuben said. Did Mama send her? He didn’t know how to answer that, so he said the only thing that felt honest. Maybe. That night, as the fire crackled and the roof held against the rain, Anakah sat across from Reuben, watching shadows dance along the walls.

“Why did you really do it?” she asked quietly. He looked at her long and full. “Because you were about to die and didn’t look scared,” he said. “Because my boy needed someone brave. Because I figured if God hadn’t taken you yet, maybe he wasn’t finished with you.” She stared at him for a long moment, then stood.

“I’m going to sleep,” she said. But her voice trembled, not from fear, from something else. Two days passed without incident. Then came the letter. The writer didn’t stop, just tossed the envelope into the dirt by the gate and kept going. Reuben found it while feeding the pigs.

The paper was wet, the ink smudged, but the meaning was clear. We ain’t done. A town that forgets justice is a town not worth keeping. If she’s still breathing by weeks end, we’ll decide for you. Reuben handed the letter to Anakah that night without a word. She read it, folded it, threw it into the fire. I’m not leaving, she said. I know. Then we prepare. He nodded. We do.

The next morning, Reuben rode into town. He didn’t wear his Sunday coat, didn’t bring Tommy, didn’t speak to anyone as he tied off his horse, and stepped into the general store. The room fell quiet the second he entered. He took his time gathering what he needed. Salt, nails, lamp, oil, cartridges. Then he turned to the room.

I know who left the letter, he said. And I know who whispered the names. I’m not going to raise my hand first, but if harm comes to my home, I’ll finish what you start. He left without waiting for a response. Back at the ranch, Anakah reinforced the windows. She showed Tommy how to load a small pistol, though he was too young to aim straight. It wasn’t about shooting. It was about not feeling powerless.

They trained in the fields at dusk, practiced signaling with lanterns, built a second barrier from logs near the back shed. Reuben set up traps in the trees. Anakah taught him how to move without noise. They were preparing for war, but not one they wanted.

On the fourth night, just after supper, Reuben placed a small wrapped package on the table. For you, he said, Anakah frowned. Why? Because it’s yours now. She opened it slowly. Inside was a locket, old silver. A photo of a woman, Clara, and a baby boy. It’s hers, Reuben said. And now it’s yours. Anakah’s fingers trembled. I can’t. You already did,” he interrupted.

That night, they didn’t sit apart. They sat together on the edge of the bed, sharing silence, sharing warmth. No promises were spoken, no lines were drawn, but something shifted. And the next morning, when they woke to find footprints in the mud outside the porch, they didn’t panic. They got ready because some things, some families are worth defending.

even if the whole town stands against you. The air smelled different that morning, like wet copper and churned mud. The kind of smell that warned animals before a storm that turned birds quiet and made dogs pace the fence line. Anakah stood barefoot on the porch, one hand pressed to the post, eyes scanning the dark line of trees beyond the pasture.

The night had left a thin layer of fog curled low over the ground, and it lingered like breath refusing to be exhaled. Tommy stirred inside, murmuring to himself in sleep, the rabbit still tucked under his arm. Reuben was already outside, boot tracks fresh in the dirt steam rising from the buckets he’d carried to the barn. She could hear the faint clatter of tools, the squeak of the stall door. Everything should have felt like routine. But nothing did.

Not after the footprints. Not after the letter. Not with the silence pressing in thicker every day. She walked to the edge of the porch. The cold wood raising goosebumps along her arms. The footprints had vanished with the last rainfall, but the knowledge they had been there had rooted into her bones.

She couldn’t sleep without one hand on the rifle now. Neither could Reuben, and every time Tommy stepped more than a few paces away, her eyes tracked him like prey might be circling. The people of the town had made their decision, not with words, but with silence. And silence was worse than gunfire. It meant planning. It meant calculation. It meant death wouldn’t come with a warning. It would come in the dark.

By the time Reuben returned to the porch, she had water boiling, biscuits rising, and her hair tied back tight. He wiped his hands on a cloth and sat beside her. “They’ll come soon,” she said without turning. “I know they’ll come more than once.” He nodded. “I don’t want Tommy here when they do.” That made him pause. You think we send him away? I think we hide him.

He shook his head. He’ll know something’s wrong. He already does. They didn’t speak after that. Not until the fire snapped and Tommy stepped out, rubbing his eyes, hair sticking up in every direction. Anakah knelt down and brushed his bangs aside. “You and your paw are going to build a fort today,” she said gently. “A fort?” Yep. under the old hay wagon.

Deep under it, a secret place just for you. He blinked. Why? She didn’t lie. Because sometimes it’s safer to hide than to fight. Reuben crouched beside them. You’ll have food, water, books, enough for a few days, but you got to promise, Tommy. You stay put until one of us comes for you, no matter what.

His lip trembled, even if I hear you. Even then, Anakah said, voice firm. He looked between them, confused and afraid, but then he straightened his tiny back like a soldier. I promise. And so they built it quietly, carefully. Beneath the rotted shell of an old hay wagon, they dug into the soft earth, laying canvas, storing blankets, tucking tins of food into corners.

Anakah wrapped a tiny Bible in cloth and slipped it beside the boy’s rabbit. Reuben carved a small wooden whistle and strung it on a string. “If you blow this,” he told Tommy, “we’ll hear you, but only blow it if you have to. If you’re in trouble,” Tommy nodded solemnly. By sundown, the boy was settled. Anakah kissed his forehead, lingered too long, then pulled back before tears could form.

Reuben knelt beside his son, pressed his forehead to the boy S, and whispered something Anakah didn’t hear. Then they sealed the hatch with hay and waited. Night came heavy with no stars and no moon, just wind and somewhere far off the distant baying of a hound. Anakah sat in the rocking chair by the door. Reuben leaned against the wall, his rifle resting across his lap.

A lantern burned low between them. Neither spoke, neither moved until the first sound came. It wasn’t much, just the faint crunch of boot on gravel, but it was enough. Reuben stood slowly, moved to the window. Three shadows, one lantern, the same trio that had come days ago. Only this time they weren’t laughing. This time they came armed.

Stay inside, Reuben said. I won’t, Anakah replied. He didn’t argue. They stepped out together, rifles low but ready. The leader, a man named Vernon, long-faced and bitter, lifted his lantern. Even in, he said. Reuben didn’t reply. You got a decision to make, Vernon continued. You hand her over now. No trouble. You can even ride into town tomorrow. Pretend it never happened.

Let us clean it up for you. Anakah stepped forward. You want to kill me in the dark like cowards. You weren’t meant to survive, Vernon spat. The judge went soft. Town got soft, but justice don’t bend for charity. Reuben’s voice cut in low. You come to my home, threaten my family, and call it justice. She ain’t family. She is now.

The second man raised his rifle. Reuben raised his. So did Anakah. Then silence. For a long, breathless moment. No one moved. And then it all shattered. A shot cracked. Not from Reuben. Not from Anakah, but from the trees. One of the men cried out and fell, clutching his shoulder. Another shot clean sharp. The lantern exploded, plunging everything into shadow.

Down, Ruben yelled, dragging Anakah to the side. Gunfire lit the night like lightning. But no one could see. The rain had started again, soft at first, then harder, turning dirt to slick mud. Vernon screamed, “Fall back!” And they did, stumbling, swearing, vanishing into the dark as fast as they’d come. Anakah crouched beside Reuben, heart pounding, smoke thick in her lungs.

“Who shot first?” she asked. “I don’t know, but a sound came then.” Hoofbeat, single, slow. From the edge of the tree line emerged a figure on horseback, hooded, rifle across their lap. Reuben raised his weapon, but the rider lifted a hand. Then he pulled back the hood. It was Sheriff Mather.

He rode forward, face set like stone. I told them not to, he said flatly. Told them you weren’t to be touched, but Vernon don’t listen. Reuben’s voice was low. You shot him. Mather nodded. Shoulder won’t die, but he’ll think twice. Anakah stepped forward. Why? Mather looked at her, something unreadable in his eyes. My wife was half chalkaw, could cook better than any woman I’ve met, and she died with the same word on her lips every night. Belong, not forgive, not run, just belong.

He turned his horse. You got a right to be here, town. Don’t decide what God already did. Then he was gone. Reuben and Anakah stood in the silence that followed. No words, just rain. And then the quiet sound of a child’s whistle faint from the hay wagon, reminding them that they were still a family, still together, still breathing, and not done yet.

By morning, the air had cleared, but the ground was a soden mess. The front yard looked like a battlefield had rolled through under cover of darkness. Muddy gouges from boot heels, scattered shell casings, broken bits of lantern glass catching in the new light like false diamonds.

Smoke still hung low where gunpowder had burned, but the scent was already fading beneath the richer smell of rain and churned soil. Anakah rose early before the rooster before Reuben. She unlatched the hatch to the hay wagon and crouched down into the hidden space beneath. Tommy was still asleep, curled around his rabbit, one hand gripping the string that held the whistle. She didn’t wake him, just smoothed his hair back and whispered, “Safe. It was enough.

” She found Reuben in the barn, already saddling his horse. His shirt was damp with sweat, though the sun had barely crested the horizon. He was angry, but not the kind of anger that exploded. It was the kind that coiled and calcified that turned into resolution and action. They’ll be back, he said, not looking at her. I know.

He cinched the saddle tighter. I’m riding into town. Not to talk. Not this time. Good. He paused, finally turning to her. You’ll stay here with him. Anakah didn’t argue, but her jaw locked. Reuben saw it. You don’t have to prove anything, Anakah. You already did. She looked at him a long while, then let me be the one to watch the ridge. He nodded.

Before he left, he walked to the hay wagon and crouched beside it, reaching in. Tommy blinked awake, eyes wide. P. Reuben took his son’s hand. You did good, boy. Just like I asked. Tommy nodded, fighting tears. I’m proud of you. The boy’s lip quivered. You’ll come back. Reuben leaned in and whispered something Anakah couldn’t hear.

Then he kissed the boy’s forehead, stood, and swung into the saddle. Anakah stood by the fence and watched him ride out. Her arms crossed, rifles slung tight across her back. By midm morning, the rain had dried into steam and the mud had begun to crack. She moved through the property like a hawk, scanning every horizon, listening for movement, pausing at each shadow to test its weight.

She didn’t let Tommy out of the wagon that day. Not until she knew what was coming. And she knew something was. It wasn’t just the threats. It was the silence that followed them. Reuben rode into town like a man done asking for permission. He didn’t hitch his horse outside the sheriff’s office.

He rode it right to the steps of the courthouse and tied the res to the iron rail. When he stepped inside, Judge Harrow looked up from his desk and blinked. “Cain,” he said, surprised. “Something wrong.” “You let this go on too long,” Reuben said without preamble. “Your silence gave it roots, and now men think justice comes out of a barrel instead of a courtroom.” The judge removed his spectacles.

You’re referring to last night. I’m referring to the last month, Reuben growled. You gave me permission to marry her. You signed the paper. You watched me walk her off that gallows. Now your town’s treating her like she’s a fugitive again. The judge sighed. Times are changing, Reuben. People don’t change as fast. Reuben leaned forward.

They’ll change faster if you remind them who writes the law. I can’t stop every drunk with a torch. You can arrest the ones who start fires. The judge stood. And who exactly do you want me to hang this time? No one, Reuben said. But next time they ride out to my ranch, I won’t shoot to warn. I’ll shoot to bury. And I want you to know why.

There was silence between them for a long while. Then the judge sat back down. “You think she’s changed?” “No,” Reuben said. “I think she’s finally being seen.” The judge nodded slowly. “You’ll need witnesses.” “I’ve got one.” He turned and walked out. Back at the ranch, Anakah felt the shift in the air before the sound reached her ears.

It was instinct, a subtle vibration in the bones, a hunter’s knowing. She was on the porch cleaning the rifle when it happened, not hooves this time. Wheels, a wagon, and not just one. She stood, slung the rifle to her back, and moved to the gate. She could see the dust now, the way it curled around the approaching figures.

Four wagons, men on horseback beside them, not towns folk this time, rougher, leaner, strangers. at the front row. Vernon, his arm still bandaged, his scowl deeper than a canyon. Behind him, a man she didn’t recognize, older, more composed, wearing a fine black coat, silver chain across his vest.

He rode like a man who never lifted anything heavier than a ledger, a banker, or something worse. They stopped at the fence. Anakah didn’t speak. Neither did they for a long beat. Then the older man stepped down. “My name is Malcolm Price,” he said with a calm, almost lazy voice. “I represent certain interests in the territory. Some of those interests have expressed concern regarding your continued presence here.

” Anakah raised an eyebrow. Concern. Price nodded. This land was manageable, predictable, until a woman escaped her sentence and a rancher decided the law was optional. I didn’t escape anything, she said. I was claimed. And therein lies the problem, Price said smoothly. Now others are wondering if they too can rewrite fate with sentiment.

She rested her hand on the rifle. Get to the point. You leave, he said simply. Today alone you vanish, and in return nothing happens. No fires, no bullets, no blood, just quiet. Anakah stepped forward slow and measured. And if I do, Price smiled thinly. Then we’ll write the ending ourselves. Anakah didn’t look away.

You came out here with wagons, not gallows. Price’s smile faded. Not yet. She leaned on the gate post. I killed coyotes before I could read. I watched my mother die in the cold. I buried men with my bare hands. If you think I’ll crawl now, you don’t know what I am.

Price studied her for a long moment, then turned back to his wagon. We’ll return tomorrow, he said. With ink or with fire, your choice. They left. She stood there until the dust settled. Then she walked back to the porch, sat down, and wrote a letter. It was short. They’re coming. Bring the law or bring a shovel.

She saddled a second horse and sent it down the trail to town with the letter tied to its mane. Then she went to the hay wagon. Tommy looked up wideeyed. Is it time? She nodded. Not yet, but soon. He gripped her hand. I’m not scared. She knelt beside him. You should be, but we’re stronger than fear. That night, she and Reuben sharpened knives, counted bullets, reinforced the doors.

And as darkness swallowed the hills again. They sat side by side at the table. He reached across and took her hand. “We’re not just fighting for us anymore,” he said. She looked at him. “I know,” she whispered. “We’re fighting for what’s next.” The oil lamp burned low. And somewhere outside the window, a crow called once. Then silence, but not peace.

Never peace. Not yet. They came at dawn. Not with a roar, but a hum. A deep, methodical rumble of wagon wheels and hooves moving slow like a funeral march pretending it was. The sky was still pale, the sun not yet warm enough to cut the chill, but the road that wound toward Cain’s ranch was already dark with riders. Six wagons, two dozen men.

A banner of dust trailed behind them, pale against the early light. Anakah was already awake. She hadn’t slept. She’d lain beside the cold hearth with her rifle across her chest and the locket Reuben had given her curled in her palm. Every few hours she’d risen to check the property.

She d sat with Tommy in the hay wagon before sunrise, kissed his forehead, and tucked the rabbit in closer to him. She whispered to him that everything would be all right, though she didn’t know if that was truth or mercy. Reuben was outside, leaning against the fence post, shotgun resting easy in his hands.

He’d saddled the mule, left it tied near the barn, a single tin pale hanging off its flank, packed with supplies just in case they needed to run. But that wasn’t the plan. They weren’t running. They’d run before separately in different lifetimes, different shapes, but not today. They’re early, Anakah said as she stepped onto the porch, dressed in a thick coat, hair braided back, revolver tied to her thigh. Reuben didn’t look at her. Cowards usually are.

The wagon stopped 50 paces out just beyond the main gate. Men began to dismount quietly, mechanically, like they’d rehearsed. Malcolm Price stepped down last. He adjusted his gloves with the same calm deliberateness he’d shown the day before. This time he wore a bowler hat and a pistol on his hip. Not for defense, for display.

Beside him stood Vernon and two others, faces tight, shoulders squared. There were more guns than yesterday, more eyes. No one carried a badge. This wasn’t law. This was something colder. Price raised one hand like a preacher greeting his congregation. “Mr. Cain, Miss or Mrs.,” he called, feigning civility. “Anica stepped forward to the edge of the porch.

You’re not here for introductions.” “No,” Price agreed. “I’m here for order.” He took a step forward. The men behind him fanned out. Reuben didn’t raise his weapon, but his grip tightened. Price continued, voice smooth and patronizing. This is not personal. It never was. But you’ve set a precedent the territory can’t afford. Anakah laughed once, quiet and bitter.

You mean a woman surviving. I mean a woman deciding. Price corrected. You broke a wheel that was meant to turn without friction. Now it wobbles and wobbly wheels tip wagons. Reuben stepped beside her. You brought 20 men to kill one woman. That says more about you than it does her.

Price sighed like a teacher weary of correcting slow students. We brought 20 men to stop an infection. That’s what this is. If others think they can defy justice because of what you did. What we did was survive. Anakah snapped. What you’re doing is murder. Price shrugged. The difference is who writes it down afterward. The tension tightened like leather left too long in the sun.

Behind Anakah, the front door creaked open. Tommy stepped out barefoot, still holding the rabbit. He blinked at the crowd, then walked to his father and took his hand. The men stared. Whispers rippled through them. “Take the boy inside,” Reuben murmured. “No, Tommy said.” Reuben crouched, eyes locked with his sons. Please. Tommy hesitated, then nodded. He turned to go.

“Wait,” Price said suddenly. “Let him speak.” Anakah’s head turned slow and sharp. “You want a child to weigh in on justice,” she asked. “No,” Price said. “I want proof of what you’ve built here.” He knelt, hat off, voice syrupy. “Tell me, son, are you afraid?” Tommy looked at him, then at Anakah, then back again. He said nothing for a long moment.

Then softly, I was before she came. The silence that followed felt like God himself had stopped breathing. Price straightened, jaw twitching. That doesn’t change what has to happen. You’re right, Reuben said. And he fired. The first shot hit the post inches from Price’s hand, splintering it. Chaos erupted.

Guns drawn, voices shouted, but Reuben didn’t stop to wait. He stepped off the porch, firing again, this time at Vernon’s feet, sending the man stumbling backward into the dust. Anakah moved too, fast and without hesitation. like a spark catching dry brush. She fired into the air, the sound cracking like thunder, Tommy ran into the house, slammed the door behind him. Price’s men hesitated.

Because they hadn’t come for a war, they’d come for a hanging for a clean ending. They hadn’t counted on resistance. The first man to charge fell with a shout, his leg hit. Not dead. Not yet, but down. Anakah spun, ducked behind the water barrel, reloaded, and popped up again, sending another warning shot just inches from a rifle barrel.

Price Dove behind a wagon. Hold fire, he screamed. Hold it. Reuben walked out from behind cover, slow, steady, shotgun still raised. I got five more shells, he called. One for every coward who thinks he’s God. Anakah stepped beside him. And I’ve got four for the ones hiding behind him. Men froze, breathless, waiting, then hooves. Not from town from the ridge.

The sheriff. Mather rode in with six deputies behind him. Rifles drawn, eyes grim. They stopped between the wagons and the porch. He raised his voice. Everyone lower your weapons. Price stood red-faced, dust on his coat. Sheriff, these people. I saw it, Mather said. Heard it, too. Cain was provoked. They defended their home.

You’re siding with a criminal. I’m upholding the law. Mather snapped. You don’t get to rewrite it because you don’t like how it turned out. Price took a slow breath. You realize what you’re doing? Yeah, the sheriff said, stopping a lynching. Price looked around, saw the eyes on him, saw the hesitation in his own men, saw the wound in the one groaning in the dirt. Then he turned to Reuben. This isn’t over. Reuben met his gaze.

It never is. Price mounted his horse, turned and left. One by one, the others followed. No one looked back. The sheriff waited until the last wagon disappeared over the ridge. Then he turned to Reuben and Anakah. You all right? We will be, Reuben said. Mather nodded once, then rode off without another word.

Anakah stood there for a long while, heart still racing, sweat cold down her back. Reuben touched her arm. It’s done. No, she whispered. It’s just beginning. They turned toward the house. Inside, Tommy peakedked through the curtain. Anakah opened the door and knelt. He ran into her arms.

She held him tight, burying her face in his hair. “We’re safe,” he asked. “For now,” she said. “But safety ain’t something that comes to you. It’s something you fight for every day.” He nodded like he understood because maybe he did. That night the family ate in silence. Not from fear but from peace earned the hard way.

After supper, Reuben sat by the hearth with his son in his lap, reading from the old Bible. Anakah rocked slowly on the porch, rifled beside her, watching the stars. The land was still, but her heart was because she knew peace is never given. It’s chosen. And she had chosen, to stay, to protect, to belong. The days that followed didn’t start with triumph.

They started with sweat, with fences that still needed mending, a roof that leaked again by the chimney, and a stubborn patch of rust on the plow blade. The sun rose like it always did, slow, indifferent, golden, as if it hadn’t watched rifles being raised, or a child whispering, “Are we safe now?” It warmed the same trees, fed the same dry grass, and wrapped its arms around the cane ranch like nothing had happened.

But everything had. Anakah felt it in her chest each time she stepped outside. The quiet wasn’t just quiet anymore. It was hard one, not the kind given freely or bought in town with coin. This kind came with scars, with sacrifice, with the memory of 20 guns and a child pressed into her lap in the dark, whispering that he wasn’t afraid, even when he was.

She moved through her mornings with the knowledge that their peace was not permanent, but it was real, and for now, that was enough. Tommy came out to the porch where she sat peeling apples for a pie she wasn’t sure would rise. He pllopped down beside her, swinging his legs over the edge, arms tucked around the rabbit like it was still the only thing in the world that made sense.

“You scared?” he asked suddenly. Anakah didn’t answer right away. She kept peeling the knife curling ribbons of skin into a pile on the wood. “Yes,” she said at last. “Of what?” She paused, looked out across the field where Reuben moved through the tall grass with a sighthe. Of forgetting, she said, of getting so used to calm that I stopped watching the horizon. Tommy thought on that a while.

P says the best way to keep something is to remember how easy it is to lose. She nodded. He’s right. He didn’t ask more questions, just leaned against her side until she could feel the warmth of his cheek through her shirt. Inside, the locket hung on the nail beside the hearth.

She hadn’t worn it in days, not because she didn’t want to, but because she no longer needed the weight of it to remind her what mattered. The memory of Clara Cain was alive in every board of that house, every corner of the field, and Anakah no longer felt like she was trespassing inside someone else’s unfinished story. She was part of it now.

That afternoon, they received their first visitor. It was a girl, no older than 16, riding bearback on a paint mare. Her face sunburned, her dress patched but clean. She rode up to the fence and stopped there, hands fidgeting around the res. Anakah stood from the porch and walked slowly to the gate.

“You the one who didn’t hang?” the girl asked, voice half defiant, half hopeful. Anakah leaned on the rail. “Depends who’s asking.” “My name’s June,” the girl said. “I live past the low ridge by the creek. My paw, he don’t treat us right. Mama’s buried out back in my brother’s runoff. Anakah nodded once slow. And what do you want from me? Just just to see, June said.

To see if it’s true that they tried to kill you and you stayed. That the man let you. He didn’t let me. Anakah said he chose me. I chose him. That’s the part they leave out. Jun’s eyes glistened. I want to know how to do that. Choose something better. Anakah opened the gate. Start by stepping inside. The girl did. Not much was said.

Reuben came out from the barn, saw her, gave a single nod. By sundown, June was washing dishes and Tommy was braiding string to make her a bracelet. Anakah watched from the doorway. The next day, there were two more. A young mother with a black eye and a toddler on her hip.

Then a boy from town who’d been sleeping behind the blacksmith shop since his father drank away the last of their home. Then another. By the end of the week, six souls shared meals at the cane table. Not all stayed. Some just rested, ate, sat by the fire, and remembered what kindness felt like. Then they moved on, their faces changed, and through it all the town watched.

Judge Harrow stopped by once with a crate of 10 peaches and a few words he didn’t know how to say right. “Guess the law s still catching up to the people it forgot,” he muttered. Anakah took the peaches. “Guess we’ll eat while it does.” Sheriff Mather visited next. “Not to warn, to ask. The stars were out.” The birch tree swayed slightly in the breeze. She carried a candle in one hand, a folded letter in the other.

She knelt beside the unmarked grave, lit the candle, and placed the letter under the stone. “I don’t know what Clara would think of me,” she said softly. “But I hope she’d see that I tried. I hope she’d see that I love the boy, that I’ve held what she left behind like something holy.” The wind tugged at her braid.

She didn’t cry. She just sat there a while breathing. Living spring came early that year. The rain stayed late, but the land didn’t mind. It had learned to bloom under weight. And so had they. Anakah didn’t call herself a wife. Not yet. Not because she doubted the bond, but because the word hadn’t mattered in the way people thought it should.

She belonged here with them as protector, as partner, as mother. One evening, Tommy brought her a string of wild flowers. “For you,” he said. She tucked them into her braid. Reuben watched from the porch, smiling just a little. And when the sun went down and the fields turned gold and blue and then black, the three of them sat by the fire, arms brushing, breath easy. Outside the land slept. Inside the family did not.

They stayed awake a while longer because sleep was easy when you knew you were safe. And belonging was not a word anymore. It was home.