June 1940. Fron Vapor stood at the edge of the Canadian prisoner camp and stared at nothing. There was no barbed wire. There were no tall guard towers with machine guns pointing down at him. There were just open fields that stretched out to the horizon. Green grass moved in the wind. Trees lined a road in the distance.

A few wooden buildings sat behind him. And that was it. He turned to the Canadian guard standing nearby. The guard wore a clean uniform. He looked relaxed, almost bored. Fron asked in broken English where the fence was. Where were the walls? The guard looked at Fron like he had asked a strange question.

Then the guard shrugged and said something that made Fron’s blood run cold. “You can go for a walk if you want,” the guard said. “Just be back by dinner.” Fron thought it was a trap. It had to be a trap. They wanted him to run so they could shoot him in the back. That’s what guards did. That’s what he had been told they would do.

This was June of 1940, and everything Fron knew about the world was about to fall apart. Just weeks before, France had been a soldier in the German army. He had worn his uniform with pride. He believed in the cause. He believed what his leaders told him. Germany was strong. Germany was superior. The enemies were weak and cruel. If you got captured, they said, you would suffer. You would starve. You would be beaten.

They told stories from the Great War from 1914 to 1918, about prisoners who died in mud and cold, about camps where men ate rats to survive, about guards who treated German soldiers like animals. Fron had believed all of it. Why wouldn’t he? Everyone in Germany heard the same stories. The radio told them. The newspapers printed it.

His officers repeated it during training. Germany was building a new world. They had conquered Poland in 1939. They had rolled through France just weeks ago. The German war machine was unstoppable. How could the enemy possibly be better than them? But then Fran’s unit got captured. It happened fast during a battle near the French coast.

One moment he was firing his rifle. The next moment, British soldiers surrounded him. They took his weapon. They tied his hands. They put him on a truck with other prisoners. Nobody beat him. Nobody shot anyone who surrendered. They just took them away. The journey that followed felt like a dream. They loaded Fron and hundreds of other German prisoners onto a ship.

The ship crossed the Atlantic Ocean. Fron had never seen so much water. For days and days, there was nothing but gray waves and gray sky. Some men got sick from the rocking, others just stared. They were going to Canada, the guard said. Fron barely knew where that was.

Somewhere far away, somewhere cold, somewhere in the middle of nowhere. When the ship finally docked, they put the prisoners on trains. These weren’t cattle cars. They were real passenger trains with seats and windows. Fron pressed his face against the glass and watched Canada roll by. He saw forests that seemed to go on forever, trees taller than buildings, rivers as wide as roads, towns with clean streets and cars parked outside houses, farms with huge red barns and green fields full of crops.

The train kept going hour after hour, day after day. Fron started to understand something that frightened him. Canada was massive. It was bigger than Germany, much bigger, and it looked rich. The infrastructure was everywhere. Power lines ran next to the tracks. Roads crossed under bridges. Factories sent smoke into the sky.

Everything looked organized. Everything looked like it worked. Fron had been told that Germany had the best of everything. The best roads, the best factories, the best technology. But looking out that train window, he wasn’t so sure anymore. This didn’t look like a weak country. This didn’t look like a place that was losing.

The train finally stopped at a small town in Alberta. Lethbridge, someone said. The prisoners got off and guards marched them down a dirt road. Fron expected to see walls rising up in the distance. He expected to see guard towers with search lights. He expected to see what a real prison camp looked like.

Instead, he saw wooden buildings arranged in neat rows. He saw a flag pole with a Canadian flag moving in the wind. He saw guards standing around talking to each other. and he saw that horrible impossible thing. No fence, no wall, nothing to keep them in, just open prairie land stretching away in every direction. The guards lined them up, and a Canadian officer spoke to them in German.

The officer said they were now prisoners of war. They would follow rules. They would work if asked, but they would be treated fairly according to international law. Then the officer said something that made no sense. He said the camp had no fence because there was nowhere to run. They were a thousand miles from Germany. If they tried to escape, they would die in the wilderness or freeze in the winter. It was safer to stay.

Fron looked at the other prisoners. They all had the same confused look on their faces. Some men whispered to each other, others just stared. One older soldier started laughing, but it wasn’t a happy laugh. It was the laugh of a man who realized something terrible. The guards walked them to their barracks.

Fron expected a dark, cold building with straw on the floor. Instead, he found a clean wooden structure with real beds. Each bed had two blankets. There were windows with glass. There was a stove in the middle for heat. There were shelves for personal items. It looked better than some German army barracks he had slept in.

That first night, Fron lay in his bed and stared at the ceiling. Outside he could hear the wind across the prairie. He could hear guards talking and laughing. He could hear nothing that sounded like a prison, and that scared him more than barbed wire ever could. The next morning, a bell rang at 6:00. Fron got up, expecting the worst.

In the German army, mornings meant cold water and hard bread. Sometimes there was weak coffee. Usually there was shouting. He shuffled outside with the other prisoners and followed them to a large building. The smell hit him before he walked through the door. Bacon. Real bacon frying in pans. Fron stopped walking. The man behind him bumped into his back.

Fron barely noticed. He just stood there breathing in that smell. When was the last time he had bacon? His mouth started watering. His stomach made a noise. Inside the dining hall, Fron couldn’t believe his eyes. Long tables filled the room. Canadian cooks stood behind a counter with huge pots and pans.

Steam rose from everything. A cook waved the prisoners forward and started putting food on their plates. scrambled eggs, three strips of bacon, two pieces of toast, real butter in little squares, a cup of coffee, sugar on the table, actual white sugar. Fran sat down and stared at his plate. This was more food than German soldiers got.

This was more food than he had eaten in a single meal in months, maybe years. He picked up his fork and took a bite. The eggs were hot and fresh. The bacon was crispy. The toast had real butter that melted into the bread. He ate slowly at first, then faster. Then he couldn’t stop. Around him, other prisoners ate the same way. Some men had tears in their eyes. Nobody spoke. They just ate.

Later, Fron found out they would get three meals like this every day. Lunch might be soup and sandwiches with meat and cheese. Dinner could be chicken or beef with potatoes and vegetables. Sometimes there was pie. On Sundays, they got extra portions. A guard told him each prisoner received about 3,000 calories per day. Fron didn’t know exactly what that meant, but he knew it was a lot.

Back in Germany, his mother’s letters talked about food shortages, ration cards that didn’t stretch far enough. Bread made with sawdust mixed in. She was probably eating half what he ate now, maybe less. The second shock came that afternoon. A guard told France he could walk around the camp. Fron asked how far he could go.

The guard pointed to a line of white stones about 200 ft past the last building. “Don’t cross that line,” the guard said. “Everything on this side is fine.” Then the guard walked away. He didn’t watch Fron. He didn’t follow him. He just left. Fron walked slowly toward the edge of camp. His heart beat fast.

This had to be a test. They wanted to see if he would try to escape, but when he reached the white stones, nothing happened. No alarm went off. No guards came running. He looked out at the prairie. Miles and miles of grass and sky. He could just walk into that. He could try to run. But where would he go? The guard was right. There was nothing out there but empty land.

And even if he walked for days, he would still be in Canada, still thousands of miles from home. Over the next few weeks, Fron discovered even stranger things. Some prisoners got to work on local farms. Canadian farmers came to the camp and asked for workers. Guards picked men who seemed trustworthy and drove them out to the fields.

The prisoners picked potatoes or gathered hay or fixed fences. The farmers gave them water and sometimes snacks. They treated the German prisoners like regular farm hands. At the end of each day, the farmers paid them 50 cents. The money went into special accounts in Switzerland that they could access after the war.

One prisoner named Klouse came back from a farm and told an impossible story. The farmer had handed him a shotgun, a real gun with real shells. The farmer wanted Klouse to shoot gophers that were eating the crops. Klouse held that gun in his hands and realized he could have shot the farmer. He could have run, but he didn’t.

Where would he go? And besides, the farmer had given him cold lemonade and a ham sandwich for lunch. The farmer’s wife had waved at him. Their kids played in the yard nearby. Clouse shot the gophers and gave the gun back at the end of the day. The farmer thanked him and said he could come back next week. Inside the camp, life got even more confusing. The Canadians set up a recreation hall with books and games. Someone donated a piano.

Prisoners who knew how to play gave concerts. Other men formed a theater group. They practiced German plays and put on shows. The guards came to watch. Everyone clapped at the end. Fron went to one show and sat there in the dark listening to actors speak his language and perform a comedy. He laughed.

Then he felt guilty for laughing. Then he felt confused about feeling guilty. There were sports, too. The prisoners organized soccer teams. Different barracks played against each other. They made a league with standings and scores. Guards helped them mark out a proper field. Someone found real soccer balls. On Saturday afternoons, prisoners played matches while other prisoners cheered.

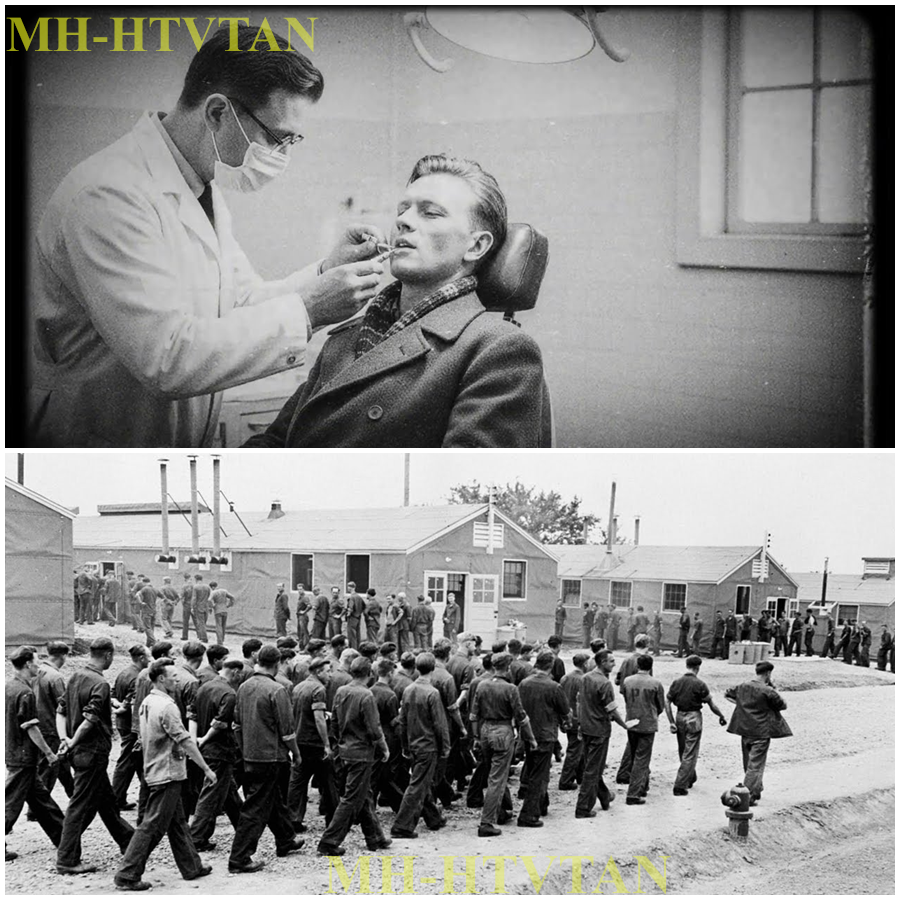

It felt like being back in school. It felt normal. And that was the problem. How could prison feel normal? The medical care shocked Fron most of all. A prisoner named Joseph got a bad toothache. The pain got so bad he couldn’t eat. Guards took him to the camp hospital. A real Canadian dentist looked at the tooth.

The dentist said it needed to come out. They gave Joseph medicine so it wouldn’t hurt. They pulled the tooth. They gave him more medicine for after. They didn’t charge him anything. Yseph came back and told everyone the dental chair was newer than anything he had seen in Berlin. The tools were clean and shiny. The dentist was kind.

Another prisoner broke his arm during a soccer game. They took him to the same hospital. A Canadian doctor set the bone and put on a cast. The doctor checked on him every few days. The arm healed perfectly. The prisoner said the hospital had x-ray machines and proper operating rooms.

He said it was better equipped than military hospitals he had seen in Germany. At night, Fron lay in his warm bed under his two blankets and tried to make sense of it all. He was a prisoner of war. He was supposed to be suffering. He was supposed to be punished. Instead, he was gaining weight. His skin looked healthier. His teeth were getting fixed. He played soccer on Saturdays.

He ate three hot meals a day. He could walk almost wherever he wanted. He went to plays and concerts. Meanwhile, his letters from home got worse each week. His mother wrote about air raids. His brother wrote about food shortages. His sister wrote about factories being bombed. Germany was supposed to be winning.

Germany was supposed to be strong. So why did the losers have so much? Why did the enemy treat him better than his own country treated its people? Fron stared at the dark ceiling and felt something crack inside his mind. A small crack, just the beginning, but it was there. Snow came to the camp in December 1943.

Fron had been a prisoner for three and a half years now. The war still raged across Europe. France heard about it in letters and sometimes from guards who talked about the news. Germany was not winning anymore. The Russians were pushing back. American bombers filled the skies over German cities. But inside this camp in Lethbridge, Alberta. Fron lived in a different world.

The cold bit hard that winter. Temperatures dropped below zero. Snow covered everything in white. But inside the barracks, stoves kept the rooms warm. Fron had three blankets now. He had a coat the Canadians gave him. He had wool socks. He was warmer than he had ever been during winter in the German army. He was definitely warmer than people back home.

His mother’s last letter mentioned heating coal being rationed. She wrote about wearing her coat inside the house. She wrote about going to bed early because it was too cold to stay up. Fron read that letter in his warm room and felt something heavy in his chest. Christmas Eve arrived on a Friday.

Fron woke up that morning not thinking much about it. Christmas didn’t mean much during war, but when he got to breakfast, he noticed the Canadian guards seemed excited. They smiled more than usual. Some of them were decorating the dining hall. They hung paper chains in red and green. They put up a small tree in the corner.

One guard hummed a Christmas song while he worked. The camp commander made an announcement at lunch. Tonight there would be a special Christmas dinner. Everyone would attend. There would be guests from town. Fron didn’t know what that meant. He went back to his barracks and tried not to think about home.

tried not to think about Christmas three years ago when he was still in Germany, when his family was together, when the world made sense. That evening, guards came and told everyone to go to the dining hall. Fron walked through the snow with the other prisoners. The sun was setting. The sky turned orange and pink. His breath made clouds in the air. When he opened the door to the dining hall, warm air rushed over him.

And the smell, oh, the smell, roasted meat, baked bread, something sweet, pine from the Christmas tree, candles burning. The tables were different tonight. Someone had put white cloths over them. Real plates sat at each spot instead of the metal trays. There were glasses for drinks, folded napkins. In the corner, the little Christmas tree had candles on it. Their light danced and flickered.

Fron stood there taking it all in. Other prisoners filed in around him. Everyone got quiet. Nobody knew what to think. Then the food came out. Canadian cooks brought huge platters to the tables. Roasted turkey, baked ham, mashed potatoes with butter melting on top, carrots, and green beans. Fresh bread rolls still hot from the oven. Gravy in bowls. Cranberry sauce dark and red.

Fron sat down and stared. This was more food than he had seen on one table in years. This was a feast. This was the kind of meal rich people ate before the war, and they were giving it to prisoners. A guard poured something into Fron’s glass. Beer. Real beer. Not much, but real. Fron picked up his fork and knife.

Around him, 300 German prisoners did the same. For a moment, nobody moved. Then someone started eating. Then everyone did. The room filled with the sounds of forks and knives on plates, of chewing, of glasses being set down, of men who had forgotten what a real meal tasted like. The turkey was perfect, juicy, and tender. The ham had a sweet glaze on it. The potatoes were smooth and creamy.

The vegetables were fresh, not from cans. The bread was soft inside with a crispy crust. Fron ate until his stomach hurt. Then he ate more. He couldn’t stop. It felt wrong to stop. This might never happen again. After dinner, the door opened and cold air blew in. A group of people walked inside.

Canadian people from the town, men and women, and even some children. They carried boxes and bags. Fron tensed up. What was happening now? But the Canadians just smiled. They walked around the tables and handed out gifts. Small things. A bar of chocolate, a pack of cigarettes, a pair of warm socks, a book.

One woman with gray hair stopped at Fran’s place. She handed him a package wrapped in brown paper. “Merry Christmas,” she said in English. France took it with shaking hands. He opened it slowly. Inside was a wool scarf, dark blue, handmade. France looked up at the woman. She smiled at him. Her eyes were kind. She patted his shoulder and moved on to the next prisoner.

Fron held that scarf and felt something break inside him. This woman had spent time making this. She had knitted it with her own hands for him, for a German soldier, for someone whose country was trying to kill her country’s men, for the enemy, and she had made it with care. The stitches were even and tight. The wool was soft. It was a good scarf, a real gift.

Someone started singing. A German prisoner with a strong voice. the words to silent night in German. Still enough, hilocked. Other voices joined in more and more until the whole room sang. Fran sang too. He hadn’t sung in years. His voice cracked. Then something amazing happened. The Canadian guard started singing. The same song but in English.

Silent night, holy night. The town’s people sang too. Two languages mixing together. Two groups of people who were supposed to be enemies singing the same song about the same night about the same hope for peace. Fron looked around the room through wet eyes.

at the German prisoners with full stomachs, at the Canadian guards with gentle faces, at the town’s people who brought gifts, at the Christmas tree with its candles, at the empty plates that had held more food than anyone back in Germany would see this year. And he understood something that made his whole world flip upside down. These people didn’t hate him. They didn’t want revenge. They pied him.

They felt sorry for him. They knew he had been lied to. They knew he came from a place that was falling apart. And instead of being cruel, they showed him what a real country looked like. A country that had so much it could give feasts to its enemies. A country that was so confident it didn’t need fences. A country so strong it could be kind.

Fron thought about the propaganda posters back home, about the speeches that said Germans were the master race, about the promises of German superiority, about the new world order they were building, and then he thought about his mother eating bread with sawdust in it, his brother in a factory that got bombed every week, his sister hiding in basement during air raids, he thought about German cities being destroyed, German soldiers freezing to death in Russia. German children going hungry. And here he sat, the enemy

prisoner, full of turkey and ham, warm, safe, with a handmade scarf from a woman who had no reason to be kind to him. The lie became clear. How could Germany be superior when it couldn’t feed its own people? How could Germany be the master race when it lost to countries that could throw Christmas feasts for prisoners? How could any of it be true when the evidence was right in front of him every single day? Fron went back to his warm barracks that night. He lay in bed holding his new scarf. Outside, snow

fell quietly. The stove glowed with heat. His stomach was full. His body was healthy. He had gained 30 pounds since arriving in Canada. 30 lb while his country starved. And in that moment, Fran stopped being a German soldier who believed in the cause. He became just a man who saw the truth.

The propaganda had been a lie, all of it, and he couldn’t unsee that now. The crack in his mind had split wide open. There was no going back. May 1946, the war was over. Germany had surrendered exactly one year ago. Fran stood on the dock in Halifax, waiting to board a ship that would take him home. Home. The word felt strange in his mind.

He had been gone for 6 years. 6 years since that day he got captured in France. 6 years since he thought his life was over. Instead, those six years in Canada had been the best years he could remember. That thought made him feel guilty and confused and sad all at once. Fron carried a small bag with his things.

Inside were English textbooks he had studied, a manual about Canadian farming methods, photographs of the camp, pictures of prisoners playing soccer, a photo of the Christmas dinner from 1943, the blue scarf that woman had given him, now worn soft from use. These were his treasures. These were proof that what happened was real.

The ship pulled away from Canada and France watched the land get smaller. Other prisoners stood on the deck with him. Nobody talked much. They all knew what they were going back to. The letters had prepared them. Germany was destroyed. Cities were rubble. Millions of people were dead. The country was divided up between the winning countries.

There was no food, no jobs, no future that anyone could see clearly. Fron pulled his Canadian coat tighter around him and wondered what he would find. The ship crossed the Atlantic, the same ocean he had crossed six years ago going the other way. But France was a different person now. He spoke English. He knew how to fix tractors.

He understood how democracies worked. He had seen what a country looked like when it treated people with dignity. He had learned that propaganda was just lies wrapped in a flag. The old Fron who believed in the cause was dead. This new Fron didn’t know what he believed in anymore, except maybe kindness and truth and the importance of a good meal.

The ship docked in Hamburg in early June. Fron walked down the ramp and stepped onto German soil for the first time in six years. The smell hit him first. Smoke and dust and something rotten. Then he looked around and his heart sank. Hamburgg wasn’t a city anymore. It was a graveyard. Buildings stood like broken teeth.

Whole blocks were just piles of bricks. People walked through the streets like ghosts. Thin people, dirty people, people with empty eyes. Fron made his way through the ruined streets. Every corner brought new horror. A church with no roof, a school that was just one wall. A park that was now a crater. He passed people digging through rubble looking for anything useful. Children with hollow cheeks begged for food.

Old women pushed carts full of broken things they hoped to trade. This was Germany. This was the master race. This was what superiority looked like. It took Frtown. Three days of walking and hitching ruids on army trucks. 3 days of seeing nothing but destruction. When he finally knocked on his mother’s door, he barely recognized her. She had aged 20 years.

Her hair was white. Her face was lined and thin. Her hand shook. When she opened the door and saw him, she screamed. Then she cried. Then she touched his face like she couldn’t believe he was real. His mother pulled him inside. The house was cold even though it was summer. Half the windows were boarded up.

The furniture was mostly gone, probably burned for heat during the winter. His mother made him sit down. She stared at him. You’re so healthy. She kept saying, “Look at you. You’re so healthy. Fron realized he probably weighed 40 lb more than her. He had color in his face. She looked gray. His mother made tea.

Real tea was gone, so it was made from dried leaves and roots. She put a small piece of bread on a plate. “This is half my ration for today,” she said. “But you need to eat.” Fron looked at that piece of bread. It was dark and hard, maybe 2 in across. This was half a day’s food. He thought about the breakfast in Canada, the eggs and bacon and toast with butter.

He thought about eating until he was full, until he couldn’t eat anymore. And here was his mother giving him half her bread. He couldn’t eat it. He pushed it back to her. They argued. Finally, they split it. Neither peace was enough to stop the hunger. Over the next few days, Fron learned what life was like now.

Food rations were 1,200 calories per day, less than half what he got as a prisoner. People stood in line for hours to get their bread and potatoes. The black market was the only place to get real food, but it cost more than anyone had. Fron’s brother was dead, killed in Russia in 1944. His sister had survived, but her husband was gone.

Nobody knew where, probably dead in a camp somewhere. People asked Fron about the prison camp. He tried to explain. He told them about the food, the warm barracks, the lack of fences, the Christmas dinner, the Canadian families who brought gifts. They looked at him like he was crazy. Some people got angry.

You got fat while we starved, one neighbor said. You were safe while we got bombed. Fron understood their anger. It wasn’t fair. None of it was fair. He had been the enemy and got treated better than the citizens of his own country. At night, Fron lay on a thin mattress in his childhood room, the same room he had slept in before the war. But everything was different now.

The window was cracked. The walls had water damage. It was cold and damp and dark. He thought about his bed in Canada. The two blankets, the warm stove, the full stomach. In Canada, he had been a prisoner, but he could walk freely. Here he was free, but felt trapped by hunger and cold and despair. Fron started having a terrible thought, a thought that made him feel like a traitor. He missed Canada.

He actually missed being a prisoner of war. How could that be possible? How could captivity be better than freedom? But it was true. In Canada, he had hope. He had food. He had friends. He had purpose. Here he had nothing but ruins and rations and memories of better days that would never come back.

Months passed. Fron tried to help rebuild. He used the farming skills he learned in Canada to work on a farm outside town. The farmer paid him in food, potatoes mostly, sometimes an egg. Friends gave most of it to his mother. He watched her eat and thought about that Christmas turkey, the ham, the fresh bread, the butter. All of it given to prisoners while German civilians starved.

The cruelty of it made him angry. But who should he be angry at? Canada for being kind to him or Germany for lying to its people and leading them into destruction. In 1948, France heard that some former prisoners were going back to Canada. The Canadian government was letting them immigrate.

There was land, jobs, a future. France thought about it every day. He could go back. He could have a real life. But what about his mother, his sister? Could he abandon them? In the end, over 6,000 German prisoners made that choice. They left Germany and went back to the country that had held them captive. They married Canadian women.

They became farmers and businessmen. They built new lives in a land that had shown them mercy. Fron stayed. He stayed because of family, because of duty, because someone had to help rebuild. But he kept his English books. He kept his photographs. He kept that blue scarf.

And on hard days when the hunger was bad and the cold was worse, he would take out those photos and remember. Remember that there was a place in the world where enemies could become friends. Where abundance was real, where kindness wasn’t weakness. Years later, France told his grandchildren about the camp with no fences. About the guard who said, “You can go for a walk if you want. about the Christmas dinner that changed everything.

And he told them the truth he learned, the truth that haunted him and freed him at the same time. Canada won the war before they ever fought us. He said, “They won by showing us what we could have been. They defeated us not by breaking our bodies, but by proving we had been lied to all along. The strongest prison isn’t made of wire and walls. It’s made of lies you believe about yourself and others.

And the only way to escape is for someone to be kind enough to show you the truth. Fron lived until 1984. He never went back to Canada, but he never forgot it either. In his mind, he could still taste that Christmas turkey, still feel the warmth of that stove, still hear Silent Night sung in two languages, still see the face of that woman who gave him a scarf for no reason except that it was Christmas and he was human and that was enough. Sometimes the greatest weapon isn’t violence. It’s showing your enemy that they were wrong about you and maybe, just maybe, wrong about