In the winter of 1812, in the quiet town of Ashbborne, Darbisha, a young girl was sold into marriage to settle her father’s gambling debt. What followed was not a love story, but a descent into humiliation, cruelty, and ultimately murder. This is the tale of Elellanena Whitmore, remembered only as the widow of Ashborne.

If stories of psychological horror, forgotten histories, and chilling mysteries intrigue you, subscribe to the Shadow Book, ring the bell, and join us as we uncover the darkest corners of the past. In the winter of 1812, in the market town of Ashbborne, Darbasher, the Witmore family fell into ruin, not by accident of weather or crop, but by the hand of its patriarch.

John Whitmore was a man known in taverns and gaming halls for his reckless wages, and by the close of that year his debts exceeded the value of his farm and household combined. Records from neighbors and creditors alike described him as a man hollowed by vice, one who gambled not merely coin, but the security of all in his charge.

When pressed for repayment, John Witmore found no allies. His fields yielded too little, his credit was exhausted, and his reputation, long since stained, left him with only one asset to bargain, his daughter. She was 13 years old at the time. By law, she was a child, but by the social codes, she was a commodity of value.

Her father understood this and used her as collateral. The groom was Edmund Blackwell, aged 29. Blackwell’s lineage offered the illusion of strength. Yet beneath that veneer, his estate required an infusion of funds. The Witmore connection, though financially weak, provided something else, an easy acquisition of control over another household, and the satisfaction of a bargain struck with desperation.

The agreement was not born of affection, nor even of negotiation between equals. It was a settlement, a balancing of ledgers. On a December evening by candle light in the office of a solicitor in Ashbborne, John Whitmore placed his signature on a document that extinguished his debts in exchange for his daughter’s future.

The witnesses recorded his trembling hand, though whether from drink, shame, or relief could not be said. Edmund Blackwell’s name followed, written in a steady script, precise and deliberate. The contract was comprehensive in its cruelty. Elellanena’s diary was set not as a gift, but as a payment against outstanding obligations.

The conditions demanded that she be transferred into the Blackwell household within weeks. It is worth noting that Elellanena herself was not present during the proceedings. At no point did her voice enter the record. In the language of the document, she was hereby conveyed, a phrase that speaks less of marriage than of property exchanged.

This was the nature of 19th century marital arrangements. Daughters could be and often were treated as instruments of settlement. For Elellanena, the moment passed without awareness. On that night she slept in her narrow bed at the Witmore home, unaware that her fate had been bound in ink.

She did not know that her father, in the shadow of his losses, had wagered her life as recklessly as he had waged his coin. She did not know that Edmund Blackwell, a man 16 years her senior, now possessed both the legal right and the social expectation to claim her as his wife. The cruelty lay not only in the contract, but in the concealment. Elellanena would not be told until the arrangements were irreversible, her protests rendered meaningless by the signatures of men and the authority of law.

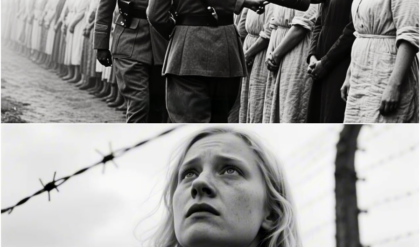

Thus, in Ashbborne, Darbisha, in the final days of 1812, a childhood ended without ceremony. It was extinguished not by death, nor by illness, but by transaction. Elellanena Whitmore’s life was sold into marriage before she even understood the terms. On a gray morning in January 1813, the parish church of Ashbborne filled with silence rather than celebration. The bells rang, but without joy.

They told heavily, not as heralds of love, but as instruments of duty among the assembled guests, a mixture of creditors, family acquaintances, and members of the Blackwell estate. The heir was strained. It was understood by all present that the union about to be sanctified was not the consequence of affection but the conclusion of a bargain.

Elellanena Witmore, scarcely 13, entered the church escorted by her father. Observers recorded that she appeared pale and bewildered, her frame slight, her dress ill-fitting. She did not speak, nor did she lift her eyes to the congregation. Her silence was not modesty, but incomprehension, a child ushered into a role she could not yet interpret.

At the altar stood Edmund Blackwell, 29 years of age, tall, rigid, and already displaying the stern features that would define his reputation in Darbisha. His estate, though diminished, carried weight in the county. His demeanor on that morning reflected not anticipation, but irritation, as though the proceedings were a chore to be endured.

Witnesses later remarked on the precise moment the disparity between bride and groom was made plain. When Elellanena reached the steps of the altar, Edmund looked upon her not with courtesy, but with disdain. He muttered, audible enough for those nearest, the word dowy, dismissing his bride as plain and unworthy even before the service commenced.

The cruelty of the remark lay in its timing, not in private, but before clergy, family, and neighbors. It established the nature of the marriage before it had even begun. The vicar, accustomed to formalities rather than disruptions, proceeded with the liturgy without hesitation. The words of the book of common prayer, steady and unyielding, filled the air.

The congregation followed mechanically, each voice subdued as though reluctant to lend volume to a ceremony they could not celebrate. Elellanena remained speechless throughout. Her responses, where required, were whispered, barely audible. Her youth, her fear, and her lack of comprehension combined to render her presence more symbolic than participatory.

She was present in body, absent in power. Edmund’s responses, by contrast, were firm and audible. He recited the vows with precision, his voice measured, his eyes never softening. The transaction was completed in tone as much as in word. The vicar pronounced them husband and wife, but the exchange contained no gesture of tenderness, no semblance of partnership.

Observers noted the unease among the guests. Some turned their eyes away from the bride’s bowed head. Others stiffened at the groom’s visible contempt. Yet no protest was raised. The contract had been signed. The debt settled, and the law sanctified the arrangement.

To question it would have been to question the very structure of society itself, a structure that regarded daughters as negotiable property and marriage as a tool of commerce. When the ceremony ended, the bells rang again, echoing through the stone nave and out into the streets of Ashbborne. Their sound carried, but their meaning was hollow.

There were no cheers, no flowers strewn, no laughter at the churchyard gate, only the dull procession of obligation, a ritual performed to conclude a transaction. The records of that day leave no description of Elellanena’s expression, only that she walked beside her husband in silence, her steps measured by those around her rather than by her own will.

Edmund’s face was set, his jaw firm, his gaze forward. Thus the marriage was sealed. Its vows were binding by law and by church, yet affection was absent. The witnesses, however unsettled, accepted it as finer. For the church bells told not for love but for debt repaid.

The marriage of Elellanena Whitmore and Edmund Blackwell, solemnized in January of 1813, produced no shared life. Within days of the ceremony, Edmund departed. His stated purpose was a mixture of business and leisure. Accounts mention visits to London clubs, extended stays in Bath, and later continental travel. The records do not suggest urgency, but preference. His absence was deliberate, and its consequence immediate.

A wife left behind without guidance, companionship, or acknowledgement. The Blackwell estate at Ashborne, though diminished in fortune, remained imposing in structure. The house was large, with highse ceiling rooms, narrow corridors, and chambers long unused. For a girl of 13, newly removed from the modest Whitmore home, the estate presented not grandeur, but vacancy.

Its spaces amplified her silence. Servants observed that Elellanena was quartered not in the master’s rooms, but in chambers resembling those of a nursery, where the furniture was small, and the walls bore traces of childhood long past. The placement reinforced her position, present in name, but not yet recognized as mistress of the household.

Household staff in their later recollections noted that Edmund gave no instructions regarding her care beyond the provision of meals and the expectation of discipline. Elellanena was to remain within the estate, her movements largely confined to its rooms and its walled grounds. There were no invitations extended to her from neighboring families, no introduction into county society, to the outside world. She was invisible. Whispers began among the servants.

They referred to her not as wife or mistress, but as the ghost. One maid testified years later that Elellanena wandered the halls with the air of a shadow seen but seldom heard. Others described her presence as spectral, a child a drift in corridors too large for her frame. In conversation, they called her the ghost wife.

a title that carried less malice than pity, but confirmed the perception that she was excluded from the life her marriage had promised. The isolation had social precedent. Among the landed families of 19th century England, young brides, especially those underage, were often sequestered until deemed suitable for public presentation. This arrangement allowed husbands to pursue business or diversion without the inconvenience of a child spouse.

What was exceptional in Elellanena’s case was the absence of preparation or transition. She was not educated for society, nor groomed for duty. She was simply left. Days within the estate blurred into indistinct routine. Elellanena occupied herself with reading when books were available or with needle work when materials could be secured.

But accounts suggest that much of her time passed in silence, without instruction or companionship. Servants were polite but distant. Their loyalty lay with Edmund, not with the child he had brought into the household. From the outside, neighbors observed only absence.

The marriage that had been the subject of whispers in Ashborn’s taverns and parlors produced no visible union. Edmund was seen at gatherings in London and Bath, his company noted, in gaming halls and theaters. Elellanena was not seen at all. The imbalance of years between husband and wife was compounded by distance. At 13, Elellanena possessed neither authority nor allies. At 29, Edmund exercised control through neglect rather than presence.

This form of abandonment, clinical in its effect, reduced the marriage to a contract without companionship, a bond without recognition. In later commentary, one clergyman described Elellanena’s condition as a living widowhood. She bore the name of a wife but not its protections. Thus the union of Witmore and Blackwell were entered under the weight of debt.

Disgel solved into silence. The child bride was left to wander the hollow rooms of Ashbborne, unclaimed and unacknowledged. She was a wife in name, a ghost in truth. When Edmund Blackwell returned to Ashbborne in the autumn of 1813, the household shifted from vacancy to oppression.

His absence had been marked by indifference, but his presence was marked by cruelty. Observers within the estate recorded a change not in affection, which had never been offered, but in authority. The silence that had once surrounded Elellanena Whitmore was replaced by commands, sharp and unrelenting. At 29, Edmund possessed both physical dominance and social authority over a wife who had only just entered her 14th year. The imbalance became visible in daily routines.

Elellanena, who might have been trained for the gentile duties expected of a mistress, was instead conscripted into labor resembling that of a servant. She scrubbed floors, hauled water, washed linens, and polished boots. Each task, though menial, was assigned with deliberate emphasis, as though intended not to maintain the house, but to reduce her dignity. Accounts from servants described the pattern clearly.

Orders were given in tones of mockery rather than necessity. When Elellanena faltered, Edmund remarked upon her clumsiness. When she succeeded, he dismissed her efforts as inadequate. His language was calculated to deny her competence, to render her effort invisible. What might have been household maintenance became ritualized humiliation.

The cruelty extended beyond the private confines of the estate. On more than one occasion, Edmund invited acquaintances and neighbors into the house, not for hospitality, but for demonstration. During these gatherings, Elellanena was compelled to serve food and wine, to fetch items on command, to kneel at the hearth and clean before the eyes of guests. Her position was neither that of wife nor of servant, but of spectacle.

One visitor later described the scene in a private letter. It was uncomfortable to witness. The girl carried trays larger to hand her her arms could bear, her face pale, her silence complete. Blackwell laughed at her awkwardness as though it were entertainment.

Those of us present understood it as cruelty, yet none spoke, for he was our host, and she his possession. This pattern illustrates a form of control not uncommon in marriages of disparity during the 19th century, where affection was absent, dominance often replaced it. A wife could be silenced not only through neglect, but through ritualized displays of subordination.

Elellanena’s humiliation served to reinforce Edmund’s authority both within the household and before the community. By treating her as an object of ridicule, he demonstrated his mastery of both property and person. For Elellanena, the effect was cumulative. Each command stripped her further of identity.

Each performance of obedience narrowed the boundary between self and servitude. Neighbors who had once whispered of her absence now spoke of her degradation. Servants instructed to neither assist nor intervene carried the stories quietly beyond the estate walls. In taverns and parlors the phrase the Blackwell girl became shorthand for a wife who was present only to be demeaned.

The cruelty was methodical, consistent and deliberate. It bore the hallmarks not of passion, but of practice, as though Edmund derived satisfaction less from her labor than from her abasement. His cruelty was not in neglect. It was in orchestration. Thus the household shifted from silence to spectacle. What had begun as an invisible union now became a visible degradation, rehearsed and repeated until it became part of the fabric of the estate itself. It was no longer neglect. It was spectacle.

By the winter of 1814, Elellanena Whitmore’s transformation from child to cattle had become apparent to all who observed her. The progression was not sudden, but gradual, measured in daily humiliations that eroded identity until obedience became reflex. Under Edmund Blackwell’s authority, she no longer responded as a person negotiating her place in a household, but as a mechanism reacting to command.

Servants provided the earliest accounts of this decline. They noted that Elellanena rose before dawn without prompting, that she anticipated Edmund’s demands before he voiced them, and that she executed tasks with the rigid precision of routine rather than the variance of human choice. Her movements, once hesitant and uncertain, became mechanical.

She fetched, carried, and cleaned without expression, her silence unbroken except for the required yes. Sir or no, sir. The effect was visible beyond the estate walls. Neighbors who glimpsed her in the courtyard or by the water pump remarked on her detachment. She did not linger in conversation, nor return greetings beyond a nod. One farmer’s wife described her as holloweyed, like a creature trained to follow rather than to live.

The comparison spread quickly. In tavern talk and kitchen whispers, Elellanena was likened to livestock, to a beast of burden that obeyed without question. The description hardened into a name when Edmund at a gathering referred to her as my goat. The remark was made in jest, delivered before guests as she knelt to scrub a stone floor.

Laughter followed, not because the company approved, but because silence in the face of ridicule was more dangerous than complicity. From that moment the label endured. Servants repeated it, neighbors echoed it, and Elellanena herself absorbed it. The cruelty lay not only in the insult but in its permanence.

Clinical examination of humiliation as a method of control shows its efficacy lies in repetition and visibility. By reducing Elellanar to an animal comparison in public, Edmund ensured that her degradation was not confined to private moments, but reinforced by communal acknowledgement. Each time the name was spoken, her identity was diminished further. Elellanena’s behavior reflected the internalization of this role.

Accounts suggest that she ceased resisting tasks, even those beneath her age and station. She carried heavy pales without complaint, scrubbed hearths until her hands blistered, and stood in silence, while Edmund ridiculed her clumsiness. Her lack of protest was not evidence of acceptance, but of survival, the instinctive retreat into obedience, when opposition brought only harsher reprisal.

The servants, though sympathetic, reinforced the pattern by treating her less as mistress and more as subordinate. She was no longer addressed as Mrs. Blackwell, but as the girl, a linguistic choice that denied her both status and maturity. In the structure of the estate, she occupied a place lower than hired staff, without authority, and without voice.

Neighbors, too, adjusted their perception. When Elellanena was seen in the village, she was not regarded as wife or child, but as extension of her husband’s will. Conversations about her rarely included her name. Instead, she was referenced indirectly. The goat, the ghost, the girl at Blackwells.

Each phrase reduced her to function, stripped of individuality. This stage of degradation marked the midpoint of her decline. Neglect had erased her presence. Cruelty had reshaped her behavior. Mockery now extinguished her identity. By the beginning of 1815, Elellanena Whitmore was no longer recognized as the daughter of a family, nor as the young bride of a notable estate. She existed only as property animated by commands.

The name clung to her like a brand. In the spring of 1815, an event occurred beyond the gates of the Blackwell estate that altered the trajectory of Elellanena Whitmore’s condition. It was not directed at her, nor did it involve her husband. It was incidental, a moment of public violence that might have passed unnoticed had she not been there to witness it. Yet, its impression was decisive.

The incident took place on a narrow lane leading from Ashbborne’s Market Square toward the estate’s boundary. Elellanena, dispatched on an errand by Edmund, walked in silence along the hedge, her head lowered, her pace unhurried. It was on this path that she encountered the scene.

A woman, slight in frame, and advanced in years, cornered by a man armed with a knife. His demand was immediate and brutal, her purse, her shawl, whatever coin she carried. What followed did not conform to expectation. The woman, though frail, resisted. She did not surrender her belongings at once, but struck at the thief with sudden force, clawing at his arm, shouting with a voice far louder than her frame suggested.

The confrontation was brief, violent, and disorderly. Startled by her ferocity and by the noise, the man faltered. Witnesses later recorded that he fled, leaving the woman shaken but intact, her possessions preserved. For Elellanena, the sight was jarring. Conditioned to silence, obedience, and withdrawal, she had come to associate weakness with inevitability. What she observed contradicted that belief.

A woman whose body bore the marks of age, whose circumstances offered little defense, had resisted an armed man and prevailed. The outcome was not triumph in the grand sense, but survival secured through refusal. Accounts suggest that Eleanor lingered after the event, standing at a distance as the woman gathered her belongings and adjusted her shawl with trembling hands. No words were exchanged between them.

Elellanena remained an observy, uh, not a participant, yet the impression remained fixed. The significance of the moment lies not in the robbery itself, which was minor and soon forgotten by the town, but in its psychological effect on Elellanena. She had, until that point, understood herself as powerless, reduced to obedience by ridicule and command.

The woman’s resistance demonstrated an alternative, that weakness did not equate to helplessness, that survival was possible even under threat. Clinical assessment of such moments suggests they operate as catalysts, shifting perception from inevitability to possibility.

For Elellanena, the incident disrupted the pattern that had governed her existence. She began to recognize that endurance was not her only option. Observation of resistance opened the conceptual space for her own. In the days following, servants noted subtle changes. Elellanena moved with greater deliberation. her silence less vacant than before.

She did not resist openly, nor did she alter her routines, but her compliance no longer carried the same mechanical quality. She appeared, as one maid later described, to be listening inwardly, as though waiting for something not yet spoken. The robbery itself faded from local record, overshadowed by other incidents of theft and unrest common to rural Darbisher in that period.

But within the confined space of the Blackwell estate, its echo persisted. Elellanena had witnessed resistance and its success. For the first time she considered the possibility of her own. If weakness could fight, why couldn’t she? By the summer of 1815, Elellanena Witmore had endured more than 2 years of neglect, labor, and humiliation within the Blackwell estate.

The incident she witnessed on the lane, the frail woman resisting her attacker, had planted in her the idea that silence was not the only response to cruelty. That spark, though faint, carried into her daily thoughts until it hardened into decision. She would attempt to speak. The opportunity came in late July, when Edmund Blackwell returned from a week’s absence in Derby.

He found Elellanena at her usual place by the hearth. her hands roar from scrubbing. According to accounts preserved through servant testimony, she rose and approached him with unusual steadiness. For the first time in their marriage, she initiated words of her own. Her statement was not dramatic but measured.

She told him plainly that their union was meaningless, that he had treated her not as wife but as servant, that she had lived in silence while mocked and degraded. She asked not for freedom but for dignity. Her request was precise, recognition of her role as wife rather than spectacle. Edmund’s initial response was laughter. Witnesses described it as sharp, unrestrained, the laughter of a man who found absurdity in the very notion of her appeal. He called her child, reminding her of her age and her place.

He told her she mistook herself for something greater than debt repaid. His tone carried amusement, but beneath it lay condescension sharpened into cruelty. The exchange might have ended there, with her silenced once more, had Elellanena not repeated herself.

She insisted, her voice firmer than before, that she could not continue in this way, that a life lived in constant degradation was no life at all. It was at this second assertion that Edmund’s amusement gave way to anger. His fury was sudden and violent.

He seized her arm, dragging her from the hearth to, “Oh, the doorway,” his voice rising with each step. Servants, startled, moved aside as he pulled her through the corridor and out into the courtyard. His words were not measured, but shouted, accusations of ingratitude, mockery of her presumption. Neighbors later reported hearing the commotion.

In the street beyond the estate’s gate, Edmund struck her before the eyes of towns people who had gathered at the sound. He forced her to her knees, shouting that she was nothing, that she belonged to him as fully as the soil he owned. The public nature of the assault was deliberate. Where humiliation had once been confined to gatherings within the estate, it was now displayed openly, a performance of mastery intended to silence not only Elellanena, but any whisper of her resistance. The effect was immediate.

Elellanena, bruised and shamed, was dragged back into the house. The neighbors, though disturbed, offered no intervention. In 19th century Ashbborne, a husband’s authority within marriage was regarded as absolute. What was seen that day was spoken of quietly, but not challenged.

From a clinical perspective, the event marked escalation. Edmund’s cruelty shifted from private ridicule to public violence. The transition reinforced hierarchy not just within the marriage but within the community, binding Elellanena more tightly to her role as possession. For Elellanena, the lesson was unmistakable. Words would not alter her condition. Reason would not deliver recognition.

Her attempt at dignity had ended not with dialogue, but with blows. In that moment, Elellanena understood reason would never deliver freedom. After the public humiliation in the summer of 1815, Elellanena Whitmore ceased her attempts at speech. The confrontation had shown her with clarity that words carried no weight against Edmund Blackwell’s authority.

What little courage she had gathered was shattered in the street, reduced to bruises on her skin and whispers among neighbors who pied but did not intervene. Yet within the silence that followed, something shifted. Elellanena’s despair did not collapse into passivity as before. Instead, it hardened. Her compliance, once mechanical, now concealed observation.

She listened with precision to the rhythms of the household, noted the times when Edmund was present, the hours when he dined, the patterns of his habits. Servants reported that she moved quietly, unobtrusive as always, but with an attentiveness that suggested calculation. What appeared as dility concealed an evolving strategy.

Clinical studies of endurance under prolonged cruelty suggest that victims often pass through stages. Submission, despair, and finally adaptation through planning. Elellanena’s progression followed this path. Her rage, once inward and unarticulated, began to crystallize into deliberate thought. She no longer asked why she suffered.

She began to ask how it might end. The method she considered was not impulsive. She did not imagine flight. Her isolation had left her with no allies and no means. She did not imagine direct confrontation. Experience had taught her the futility of words and the violence of resistance. What remained was subtlety. An end delivered quietly under the guise of routine.

Poison presented itself as the only viable solution. It required no strength, no open conflict, no witnesses. It was in essence an extension of her condition. Silent, concealed, and methodical. Accounts suggest that Elellanena began to observe not only Edmund’s habits, but also the herbs and tying nectures kept within the estate.

Country households of the time often maintained stores of medicinal plants, fox glove, hemlock, belladona. Their legitimate use accepted, their dangers well known. Neighbors later recalled seeing Elellanena at the market purchasing herbs under the pretense of household remedies. No suspicion was raised. It was common for women to maintain knowledge of simple cures. What was uncommon was the intent with which she gathered them.

Her silence at the stalls, her careful selection, her measured questions, all pointed not to curiosity, but to design. Her demeanor within the estate reflected the same shift. Servants noted that she no longer flinched at Edmund’s commands. She carried out tasks with composure, neither hurried nor hesitant.

Her eyes, once vacant, now carried a stillness that unnerved those who observed her closely. It was as though she had retreated inward, conducting calculations invisible to those around her. From a detached perspective, this stage marked the conversion of suffering into agency. Elellanena’s condition had stripped her of speech, identity, and dignity.

What remained was intent, a cold, deliberate shaping of the future through means available to her. The choice of poison was not merely practical, but symbolic. Just as her degradation had been administered slowly, invisibly through repeated humiliations, so too would her response be gradual and unseen until finality arrived.

She did not confide in anyone. No record suggests she spoke of her thoughts, even in fragments. The evidence lies only in the recollections of her altered behavior and in the later outcome of her plan. But those who studied her life afterward agreed that the transition occurred during this period.

The moment when despair no longer dissolved her, but refined her into calculation. Elellanena’s silence was no longer the silence of defeat. It was the silent of preparation. Each day that passed without resistance concealed the careful gathering of knowledge, the slow assembling of opportunity. Her mind was no longer pleading. It was measuring.

By the autumn of 1815, Edmund Blackwell’s finances had begun to mirror the decay of his character. Though heir to a notable estate, his reckless expenditures in London and Derby, gaming tables, taverns, and speculative ventures had left him exposed. Creditors, long patient in expectation of repayment, arrived at Ashborne to demand settlement.

Records describe three men, tradesmen of moderate standing, whose claims against Blackwell were not insubstantial. Their arrival was not ceremonial, but confrontational. They entered the estate not as guests, but as collectors, their voices low, their tone edged with threat. The confrontation occurred in the dining room with servants stationed nearby to observe, but instructed not to interfere. The exchange began with formality.

Ledgers were presented, amounts recited, interest calculated. Edmund dismissed the figures with contempt, insisting that payment would be forthcoming in due course. His posture conveyed confidence, but his creditors pressed harder. Their patience, they said, had expired. What had once been business was now survival. The discussion grew sharper.

One of the men, identified in later testimony as a supplier of spirits, leaned across the table and delivered a remark that would lodge itself in Elellanena Whitmore’s mind. The next cup you drink may be your last. The phrase, half metaphor, half menace, carried the weight of a threat too pointed to ignore. Edmund responded with anger, striking the table and ordering the men to leave his house. They did not comply immediately.

Instead, they stood their ground, reminding him of the consequences of delay, seizure of property, loss of reputation, perhaps worse. Only after several minutes of raised voices and insults did they withdraw, leaving Edmund flushed with rage, pacing the length of the room. The servants who witnessed the scene recorded their impressions.

Thor A noted that Elellanena, as was customary, stood quietly at the edge of the room, serving wine and clearing plates. She neither spoke nor moved beyond her duties. Yet her stillness concealed attention. The words of the creditor, “The next cup you drink may be your last,” did not pass her unnoticed. For Elellanena, the confrontation introduced an unforeseen element.

Until that moment, her plan had been solitary, conceived in silence, and concealed within her own mind. But now circumstance provided a framework. The creditors had spoken openly of Edmund’s death, their threat overheard by others. Should Edmund fall, suddenly, suspicion would not fall upon her alone. Blame might shift naturally toward those who had voiced menace and carried grievance.

Clinical analysis of her condition suggests that this moment was decisive. Opportunity, when aligned with intent, transforms calculation into action. Elellanena’s plan, once abstract, found its cover in the anger of men who sought repayment. Their threat became the alibi she could never have manufactured on her own.

Edmund, still seething from the encounter, ordered more wine, dismissing the incident as mere bluster. To him the men were pests to be swatted away with arrogance. To Elellanena they were unwitting collaborators. Their words had opened the path she needed, and their presence in the household provided the means to divert suspicion when the time came. The estate resumed its routines that evening. Edmund drank heavily.

servants moved about their tasks, and Elellanena returned to her silence. Yet within that silence, a conclusion had formed. The creditors had supplied not only threat, but cover. Their menace, overheard and remembered, would shield her design. Their threat would become her weapon.

By late 1815, Elellanena Whitmore’s plan had matured into action. Months of silent observation and careful preparation converged into a single course. Edmund Blackwell would die not by open confrontation, but by poison, administered in plain sight during the ordinary rituals of his household. The tools of her design were neither exotic nor imported.

Country homes of the period maintained stores of medicinal herbs gathered for treatment of fevers, stomach ailments, or sleeplessness. Elellanena under the pretense of household management secured access to these supplies. Hemlock, Belladona, and fox glove, plants known equally for their curative and fatal properties, were available in dried form, their risks well understood by apothecaries, though rarely spoken of by wives and servants.

Elellanena’s method was incremental. She studied the textures and tastes of the herbs, testing quantities in broth and wine to observe bitterness and concealment. Servants later recalled her lingering at the kitchen hearth, stirring pots with unusual focus, or requesting measures of spices to mask unfamiliar flavors. These actions aroused no suspicion.

In households where the master demanded constant labor, it was common for wives to extend their duties into the kitchen. The timing was precise. Edmund drank heavily, particularly in the evenings. Wine provided the perfect vehicle, rich in taste, strong in aroma, capable of concealing even the bitterest tinctures.

Elellanena selected a night when the household was calm, the servants dispersed, and Edmund already softened by drink. The moment itself was ordinary. Edmund sat at the head of the table, his boots still marked with dirt from the courtyard, his voice carrying commands as if the meal were another performance of authority.

Elellanena poured the wine without hesitation, her hands steady, her silence unbroken. Into the cup she had introduced the voice, a tincture measured not to kill instantly, but to weaken gradually, allowing the scene to unfold as if illness or exhaustion had overtaken him. Edmund raised the cup, unaware. He swallowed, then paused, remarking that the wine was uncommonly smooth.

The words, recorded later by a servant standing nearby, carried the crulest irony. Each compliment was directed not to the vineyard, but to the very substance that would end his life. Elellanena, standing beside him, betrayed no reaction. The progression was slow. Edmund continued drinking, his voice rising in mockery, as it often did, his laughter filling the hall.

Yet beneath the noise, his body began to falter. His speech slurred, his hand trembled on the cup. At first he dismissed it as fatigue, cursing the demands of creditors and the burdens of his estate. But the weakness spread, visible in the slump of his shoulders, the palar of his skin. servants hesitated at the edges of the room, uncertain whether to intervene.

Elellanena remained composed, clearing dishes, pouring another measure into his cup. Edmund drank again, seeking comfort in the familiar ritual, unaware that each swallow advanced his decline. From a clinical perspective, the act bore the hallmarks of an experiment conducted with precision. Dosage, concealment, and timing aligned.

The stillness of the household, the absence of visitors, and the complacency of the victim all contributed to the success of the plan. Elellanena’s role was not reactive, but deliberate. The silence of years transformed into method. As Edmund’s strength ebbed, he leaned back, muttering that the wine carried an unusual depth. It was his final compliment, delivered to the substance of his undoing.

His hand released the cup, which struck the table and rolled, spilling red across the wood. His eyes closed, his body sagged, and the household entered silence. For Elellanena, the act was complain. What had begun in humiliation now ended in calculation. Cruelty endured for years was met with a single measured response.

Each sip narrowed the distance between cruelty and silence. The death of Edmund Blackwell, though slow in its onset, presented Elellanena Whitmore with a problem that required immediate resolution. Poison, if left unexplained, risked suspicion. A husband felt suddenly within his own house might draw scrutiny toward the silent wife who poured his wine.

To secure her escape, Elellanena needed to convert private death into public crime. The solution lay in staging. The confrontation with creditors weeks earlier had supplied both motive and menace. Their threat, “The next cup you drink may be your last,” had been heard by others. Elellanena understood its value.

If Edmund’s body were discovered, not within the estate, but in the open, marked with signs of retribution, suspicion would naturally fall upon those men. Her role would be erased, concealed beneath the weight of their words. The work began after midnight. Servants dismissed from duty had retired to their quarters. The house was silent, its corridors dim.

Edmund’s body, heavy with the rigidity of collapse, remained at the dining table. Elellanena moved with steady calculation, securing a cloak around his shoulders to mask the stiffness of death. The task demanded strength beyond her size, yet desperation supplied it. She dragged him first through the hall, the sound of his boots striking the floor softened by layers of carpet.

At the threshold, she paused, listening for movement among the servants. Hearing none, she opened the door and pulled him into the night air. The cold met her face, sharp and bracing, but she continued without hesitation. The streets of Ashbborne at that hour were deserted. The town, accustomed to early labor and early rest, lay in silence. lamps flickered faintly, their light uneven.

Elellanena moved in shadow, guiding the body along narrow lanes, pausing when the weight grew unbearable. At intervals she adjusted his limbs, positioning them to avoid suspicion of dragging, though the effort left marks in the dirt. Her path led toward the market square, the center of the town, where discovery would be swiftest at dawn.

There, under the shadow of the church tower, she left him. Before stepping away, she produced the final element of her design. A note written in a hand, careful but unpracticed, it bore the warning she wished to attribute to his creditors. This is the fate of men who fail their debts.

The words were pinned to his coat, secured against the night wind. Its bluntness required no elaboration. Those who had threatened him were known. Their anger was documented. The note served as confirmation, not invention. Elellanena adjusted his cloak, arranged his arms to suggest collapse rather than careful placement, and stepped back.

The stillness of the square absorbed the scene. She turned and retraced her path, her steps measured, her face expressionless. Within the estate, she returned to her chamber, extinguished the lamp, and lay in silence. The clinical precision of the act is notable. At no point did Ellanena display panic.

Her actions aligned with method, each step anticipated, each risk considered. The physical strain of dragging a man nearly twice her weight through the streets did not deter her. What years of humiliation had instilled was endurance, and that endurance she applied to concealment. By dawn, Ashbborne would find its master dead in the square.

When the body of Edmund Blackwell was discovered in Ashborn’s market square at dawn, the town was unsettled, but not surprised. His creditors had been vocal, their threats overheard, their anger documented. The note pinned to his coat confirmed suspicions too readily entertained. Within hours, the story had fixed itself. Edmund Blackwell had been killed in retribution for unpaid debts.

Elellanena Whitmore’s role in this narrative was immediate and sympathetic. At only 14 years of age, she was cast not as participant but as victim. The town saw her as a child bride widowed by circumstance. Her life shaped first by her father’s gambling, then by her husband’s ruin.

Neighbors who had once whispered about her humiliation now spoke of her misfortune. The funeral offered her the stage on which to solidify this perception. Accounts describe her at the front of the church, clothed in mourning black, her face pale, her body trembling. She wept openly, the sound carrying through the nave.

Servants testified that her sobb seemed unrestrained, her grief unstudied. Observers conditioned to accept outward displays as proof of inner truth believed her suffering genuine. Yet analysis of her behavior reveals a pattern of careful performance. Her tears fell at precise moments during the vicar’s reading of scripture, at the lowering of the coffin, at the mention of Edmund’s name.

Between these episodes she composed herself quickly, her breathing steady, her eyes lifting to meet those of the congregation. Each glance reinforced the image of innocence, of youth bowed beneath tragedy. Neighbors responded accordingly. Women whispered prayers for her future, pitying her for the years stolen. Men shook their heads at Edmund’s waste and cruelty, their anger directed outward toward the creditors.

Gifts of food and coin arrived at the estate within days, offered not to secure favor, but to relieve what was perceived as hardship. Elellanena accepted them with quiet gratitude, never protesting, never elaborating beyond her role as bereieved. The manipulation lay not in words, but in silence. Elellanena did not need to invent explanations.

The town supplied them. She allowed others to speak of her as the poor widow, the child left alone, the innocent caught in ruin. Each title shielded her. By saying less, she allowed sympathy to grow unchecked. From a detached perspective, her performance demonstrates the effectiveness of conformity to expectation.

In early 19th century England, widows were judged by their outward grief. Sob, pale demeanor, and withdrawal from society were all considered marks of virtue. Elellanena embodied each with precision. Whether her tears were genuine or not, they fulfilled the requirements of the role and thus became accepted as truth. Even those who had witnessed her humiliation under Edmund’s hand reframed their memories.

Where once they saw her as a girl degraded, they now spoke of her as a girl wronged. Cruelty, in retrospect, became evidence not of weakness, but of victimhood. Her position shifted from object of ridicule to object of pity. This transformation secured her safety. In the absence of suspicion, no one questioned her presence at the final meal, nor her role in pouring Edmund’s wine.

The creditors, already burdened by their public threats, carried the blame with little resistance. Elellanena, meanwhile, strengthened her position with each convincing display of grief. Her mourning was convincing, perhaps too convincing. In sorrow, she found her shield. The death of Edmund Blackwell did not close with the funeral. In its aftermath, Ashbornne stirred with questions.

While the note pinned to his coat pointed directly to creditors, the clarity of the accusation itself raised unease. In towns accustomed to quiet debts and quiet reprisals, the spectacle of a body displayed in the square struck many as too deliberate. An inquiry was opened, informal at first, conducted by local constables under pressure from Edmund’s surviving kin.

They interviewed the men whose threats had been overheard weeks earlier. The creditors admitted their anger, their frustration, and their demands for repayment, but denied responsibility for the killing. Each insisted the note was either fabrication or exaggeration meant to divert suspicion. Their protests were logical, but their reputations weakened them.

For men already known for hardness in collection, denial carried little weight. The town divided. Some accepted the simplest explanation, that men cheated of repayment, had carried out their warning. Others muttered about inconsistencies. If the creditors had intended murder, why leave so public a display? Why risk exposure in the town square when revenge could have been secured quietly? The questions lingered, but found no firm answers.

Within this atmosphere of uncertainty, Elellanena Witmore’s conduct was observed closely. Neighbors noted her composure, her ability to move through grief with a calmness uncommon in one so young. At 14, she wore widow’s dress with an air more practiced than expected. Some whispered that her mourning, though convincing, seemed too precise, too disciplined. Yet, in a society where outward control was admired, suspicion did not solidify.

Investigators found no evidence to implicate her. The servants questioned about the night of Edmund’s death, confirmed only that Elellanena had served wine at the evening meal. None admitted to seeing anything unusual. The poison, undetected in a time before forensic testing, left no trace. The dragging of the body, though evident in scuffs along the estate’s lane, was attributed to those who staged the note.

The very absence of proof secured her position. From an analytical perspective, the inquiry demonstrates the fragility of justice in cases governed by reputation rather than evidence. Edmund’s cruelty, widely known, lessened sympathy for his fate. The creditors anger, openly spoken, made them plausible villains.

Elellanena’s silence, her youth, and her careful adherence to the image of berieved widow shielded her from meaningful accusation. Still, whispers persisted. Some claimed her grief lacked spontaneity, that her tears fell at moments too convenient. Others remarked on her sudden poise, her ability to host visitors, and receive condolences without faltering.

A few servants, speaking privately, admitted unease at her stillness during the weeks before Edmund’s death. Yet none of these suspicions coalesed into action. The inquiry concluded without charges. The creditors, though never convicted, bore the weight of suspicion in the community, their trade suffered, their names tarnished.

Elellanena, by contrast, emerged untouched, her position recast from degraded wife to pitted widow. Ashbborne sought justice, but justice never found her. Suspicion circled her, but never settled. With the inquiry concluded and suspicion diverted toward Edmund Blackwell’s creditors, Elellanena Whitmore entered a new phase of existence. At 14 years of age, she was both widow and hes.

Edmund’s estate, weakened, though it was by debt, passed formally into her control. What had once been a prison of humiliation now became a platform for her reinvention. The transformation was visible first in her public role. No longer hidden in nursery-like rooms, Elellanena assumed the outward duties of household mistress.

Visitors were received at the estate, condolences accepted, meals hosted. Her conduct was marked by composure. where once she had been silent under command, she now spoke with quiet authority, directing servants with efficiency. Neighbors who had pitted her as victim began to respect her as widow. Wealth alone did not secure this position. Sympathy reinforced it.

In the eyes of the town, Elellanena had suffered first at the hands of a cruel husband, then through his violent death. These perceptions insulated her. To criticize her was to appear callous. To question her grief was to defy the image the community had built around her. In this way she became untouchable. From a clinical perspective her emergence illustrates the power of role reversal in social standing.

The same community that had once whispered about her obedience now elevated her to the status of tragic figure. The same household that had witnessed her degradation now carried out her orders. Her survival had been secured not only by action, but by perception. Yet beneath this composure, traces of her past remained evident.

Servants observed her habits at night, pacing the corridors in silence, pausing before locked doors, extinguishing lamps repeatedly as though ensuring darkness held. She ate sparingly, often pushing food aside as if uncertain of its taste. When spoken to suddenly, she startled, her hands tightening as though bracing for reprimand.

These details suggest that her freedom was incomplete. Trauma, once ingrained, continued to shape her behavior. The estate itself bore marks of the transition. Rooms where Edmund had staged her humiliation, were closed off, their doors locked, and their contents covered in cloth. The dining hall, where he had once mocked her as my goat, remained unused for months.

Guests were entertained elsewhere, the past avoided by rearrangement of space. Such gestures reveal the effort not only to govern, but to erase, as though by sealing rooms she might confine memory. In legal terms, Elellanena’s position was secure. With Edmund gone and no heirs, she controlled both land and property.

Relatives who might have contested her inheritance withdrew, unwilling to provoke further scandal. The creditors, weakened by suspicion, had no leverage. Ashbborne accepted her as a widow of means, her authority legitimized by the absence of challenge. But in personal terms, her freedom was more complex.

She had removed Edmund, but she had not removed the years of degradation. Those who saw her closely remarked on the stillness of her expression, the precision of her movements, the absence of laughter. She had gained control of her circumstances, but not released from their imprint. Thus, Elellanena Whitmore entered her new life.

No longer servant, no longer ghost, no longer subject to cruelty. She was mistress of the Blackwell estate, cloaked in sympathy, and insulated by wealth. Yet each day carried reminders, in gestures, in silence, in the locked rooms of her house, of what had been endured. She was no longer a wife, but she was not yet free of his shadow.

In the decades that followed Edmund Blackwell’s death, Elellanena Whitmore’s name never fully departed the whispers of Ashbborne. She remained at the Blackwell estate through her early adulthood, managing its affairs with quiet efficiency. Visitors described her as composed, dignified, and marketkedly reserved.

She neither remarried nor sought wider society. Her life was conducted within the confines of the estate and the parish, steady and unremarkable on the surface, yet always shadowed by the manner of her husband’s end. The town remembered her in fragments. To some she was the tragic child bride, forced into marriage at 13, humiliated in public, and widowed before she reached maturity.

They saw her survival as evidence of endurance, her composure as a sign of inner strength. In their telling, she was victim first to her father’s debts and then to Edmund’s cruelty. A girl who bore suffering in silence and emerged with dignity. Others were less certain. Among the older generation, particularly those who had witnessed her transformation from obedient child to poised widow, suspicion lingered.

They recalled the creditors threats, but also Elellanena’s calmness after the death. her tears that seemed too perfectly timed. To them, the note pinned to Edmund’s coat was too convenient, too deliberate. They whispered that Elellanena had seized an opportunity, that the creditors were framed, that her silence concealed guilt as much as grief. No proof ever surfaced.

The poison left no trace in a time before chemical testing. The dragging of the body, though clumsy, was attributed to others. The inquiry closed without conclusion, leaving only speculation. Elellanena herself never spoke of that night.

In conversations about her husband, she confined her words to formal acknowledgements of his death and the burdens he left behind. She neither defended him nor accused him, neither explain inid nor denied. Her silence preserved her. As the years passed, the community’s judgment divided along lines of perception. To the sympathetic, she embodied resilience. The girl who became the widow of Ashbborne, a figure of pity and respect.

To the doubtful, she embodied calculation. A child who grew into cunning, who rid herself of a cruel master and outsmarted justice. Both narratives endured, neither proven, both repeated. From a detached perspective, Elellanena’s story illustrates the fragility of truth when buried beneath reputation.

The absence of evidence allowed competing versions to survive side by side. One cast her as victim of circumstance, the other as perpetrator of design. The truth, whatever it was, remained sealed behind her composure and her refusal to confess. Elellanena Whitmore died in 1852 at the age of 53. Her burial was attended by towns people who still spoke of her as the widow.

The estate passed quietly to distant relatives, her line extinguished. Yet even at her grave, the question lingered. Who had she truly been? Was she the child sold by her father’s desperation, marked forever by cruelty she never invited? Or was she the calculating young widow who turned humiliation into strategy, transforming poison and opportunity into freedom? The documents, the testimonies, the whispers of Ashbborne never resolved the matter.

History remembers her as the widow of Ashbornne, but history cannot decide whether to absolve or condemn her. Elellanena Whitmore’s story ends in silence. A widow mourned by some, suspected by others. Was she freed by courage or consumed by rage? That answer may never be known. What do you think? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

And if you want more tales of dark history and psychological horror, don’t forget to like this video, subscribe to the Shadow Book, and ring the bell. Because the past is never as sir, quiet as it seems.