He gave her the last coin he had, expecting nothing in return. But when morning came, she stood at his door with tears in her eyes and two newborns in her arms. The wind kicked up dust across the edge of Mercy Ridge as Boon Fletcher dropped the last dollar he owned into the widow’s trembling hand.

No one saw it. No one cared. He didn’t make a speech. He didn’t even look her in the eye. He just tipped his hat, turned, and walked away like it hadn’t just cost him his last chance at supper. Boon had made peace with hunger years ago.

It came and went like the wind, and he’d learned not to chase anything that didn’t chase him back. Mercy Ridge didn’t chase anyone back. It let you wither, starve, go quiet, and disappear without so much as a whisper. That’s why Boon kept to the outskirts. Less noise, fewer faces, no expectations.

And that day, when he found her slumped by the livery with her shawl torn and her eyes wet, he hadn’t asked questions, just gave what little he had. She hadn’t begged, that was the thing. She was holding a bundle in her arms, and her voice was from something deeper than thirst. Don’t want charity, she’d murmured. Just one night where they can sleep warm. Boon didn’t ask who they were.

He didn’t even check what was under the bundle, but something about her, maybe the fight left in her, maybe the crack in it, held him still. That and the fact that nobody else had. Take it, Boon had said simply, handing over the coin. Ain’t much. And then he’d walked off. He didn’t look back. He’d learned not to look back. Looking back was how pain followed you home.

His cabin sat on the edge of the timber line, built with his own hands in solitude. Three walls of pine, one stone wall facing the hearth, roof patched too many times, door that stuck in winter, but it kept the cold out, and that night that was enough.

He boiled water for tea with no leaves, then sat by the fire, watching the wood burn down low, wondering if a man could get full on smoke and memory alone. He figured he’d find out by morning. Sleep came slow. It always did. the kind of slow that made your bones itch and your thoughts wander back to people you debured too far from town to mark with a cross.

He didn’t dream anymore. Not really. Just closed his eyes and waited for the dark to pass. But dawn came different. Not with the usual quiet frost and the whisper of melting snow slipping from the roof, but with a sound he hadn’t heard in years. A knock. It was soft, uncertain, like someone hoping no one was home. Boon stiffened. No one knocked out here.

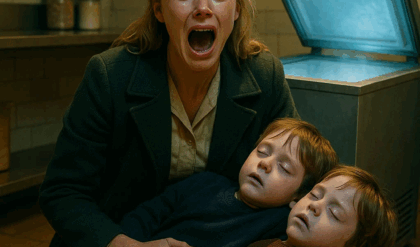

They either barged in with guns or didn’t come at all. His boots hit the floor with a slow scrape. He grabbed the iron poker from beside the fire, instinct more than fear, and eased to the door. The knock came again, three times faint. Boon cracked the door and there she was, the widow from town. Only now she wasn’t just holding a bundle, she held two.

Her hair was wind tangled and dusted with snow. Her lips were blue. Her shawl hung off one shoulder, and the babies in her arms looked like they’d been born only hours ago. Boon didn’t speak, didn’t need to. She looked up at him with eyes swollen from sleeplessness and something else he couldn’t name.

I didn’t know where else to go, she said, voice breaking as she swayed slightly on her feet. He stepped aside without a word. She stumbled in, not walked, stumbled like the moment her boots crossed that threshold. Whatever was holding her together snapped in half. Boon caught her elbow before she crumpled entirely and eased her down onto the ragged old cot near the hearth.

The twins didn’t cry. They didn’t make a sound. just blinked up at the ceiling with the quiet helplessness of newborns too tired to scream. Boon knelt beside her. They yours. She nodded, breath shaking. Mine and his, but he’s he’s gone. Boon glanced at the door, then back at her. Gone how? Shot three days ago.

Her hand gripped the babies tighter. We buried him near the river. I kept walking. He didn’t ask why she walked or why she chose this direction or how she knew where to find him. He just stood up and went to the stove, poured the last of the boiled water into a mug, and handed it to her. She took it without thanks, like someone passed the point of pleasantries.

Boon found himself staring at the twins. One had a mop of dark curls and the other barely a fuzz of gold. Tiny, silent, breathing slow. He hadn’t seen a baby up close since his brother’s girl gave birth six winters ago. Back when they still spoke. You got names? He asked finally, voice lower now. She looked up. I’m Ruth. That’s Clara. She touched the dark-haired baby. And that’s Seth. Boon nodded slowly. I’m Boon.

A pause stretched between them, filled only by the crackle of the fire. I remember, Ruth said. from town. The dollar. Boon shrugged. Wasn’t doing me no good. It saved us, she whispered. I bought milk, got a room, had the babies there. It gave me one night of not dying.

Boon didn’t know what to say to that, so he said nothing. She looked around the cabin, eyes softening for the first time. It’s quiet here. He nodded. Quiet keeps folks alive, and sometimes it kills them. that hung in the air heavier than the smoke. By afternoon, the snow had picked up again. The pines whispered under its weight.

Boon gathered wood while Ruth lay curled around her children, asleep like a stone dropped in a riverbed. When he returned, she stirred. “I’ll leave in the morning,” she murmured without opening her eyes. “Where, too?” “Wherever God tells me to go next.” Boon didn’t laugh, didn’t scoff. He just nodded. “You don’t have to go,” he said after a while. “Cabin small but warm.

” She opened her eyes, weary and glassy. “You don’t know me. I know what it’s like to run out of places to knock.” Ruth turned her head away. The baby stirred slightly, but didn’t cry. Boon went back to the hearth, added another log, and watched the sparks jump. That night, the storm pressed harder. Wind whistled through the gaps in the roof boards, and Boon rolled another quilt under the door.

The children slept soundly. Ruth did not. She lay awake, hands gripping the quilt, eyes wide in the dim firelight. “I thought he’d make it,” she whispered suddenly, voice barely audible. “We saved for the journey west, for land, for hope. He said we’d build a house with a porch.” Boon didn’t move, just listened. He was shot for a horse he didn’t even steal.

Left me to dig the grave with my bare hands. Boon’s jaw tensed. The West don’t wait for dreams to catch up. No, she agreed. It doesn’t. The silence returned, but it felt less sharp now, more like breath shared between two people too tired to be strangers. By morning, Ruth was sitting by the window, holding Clara and watching the snow ease.

I thought about leaving anyway, she said. Didn’t want to be a burden. You’re not. She turned to him unsure. Why’d you help me? Boon didn’t answer right away. Then he said, “Because no one helped my sister. She died with a baby in her arms, too. Maybe if someone had.” He trailed off. Ruth blinked hard. I’m sorry. Don’t be. You’re here. That counts. She looked down at the children. It has to count.

Then came the sound. Boots outside, heavy, crunching in the snow. Boon rose, hand reaching for the rifle, leaning near the hearth. Ruth went still. The knock that followed was nothing like hers had been. It was loud, intentional, and Boon knew without a doubt. Someone wasn’t here for kindness.

The knock came again, harder this time. Three sharp wraps that didn’t ask for entry so much as declare it was owed. Boon didn’t move at first, just stared at the door like he could will it to disappear. Ruth had gone pale, arms tightening around Clara and Seth as she backed slowly toward the hearth, trying to keep her body between the children and the entrance.

Boon’s fingers wrapped around the rifle stock. It wasn’t loaded, not yet, but the click of the bolt and the weight in his hands gave him just enough time to pull in a breath and steady himself before the door creaked under another knock. This time, a voice came with it. Male cold. Boon Fletcher, I know you’re in there.

Boon stepped forward and cracked the door an inch, the iron latch still holding. Through the narrow opening, he saw three men on horseback. One had dismounted, boots crunching on the packed snow. The others waited behind, horses snorting in the cold. All of them wore dust dark coats, too clean for cow hands, too heavy for drifters.

The man at the door removed his hat with a slow deliberate motion. “Name s Daryl Vain,” he said, eyes like black coals. Looking for a woman came through Mercy Ridge. Name of Ruth Ren riding alone. Might have had a child or two. Boon didn’t answer. Vain tilted his head, smile tight.

Ain’t saying she did anything wrong, but folks back east are looking for her. Family dispute, you understand? Behind Boon, Ruth’s breath caught. Vain stepped forward. Boots right up against the threshold. “You’re a quiet man, Boon,” he said. “Always have been. But now’s not the time to start keeping secrets.” Boon didn’t move from the door. “No one here but me.” A beat passed.

Vain didn’t blink. He turned his head slightly, as if listening past the crack in the door. You always keep the fire burning this hot for just yourself. Boon didn’t flinch. Cold morning. Behind Vain, one of the riders shifted in his saddle. Let us in. Well check for ourselves. Boon’s voice was calm, almost bored. That’s not how it works out here.

Vain narrowed his eyes, but he didn’t push. Not yet. If you see her, he said finally, stepping back, you let us know. She’s got no business disappearing with what don’t belong to her. With that, he turned, swung up into his saddle, and nodded to the others. The horses wheeled around, hooves thuting in rhythm as they rode off down the trail back toward town.

Boon closed the door and dropped the latch. Then he turned to Ruth, who was still frozen by the hearth. You want to tell me why men like that are looking for you? Ruth was shaking. Not from cold. I didn’t steal anything, she whispered. I didn’t. Boon sat down slowly on the edge of the table. That man seemed pretty sure you did.

She hugged the twins closer because I left. Because I walked away from a family that thought I was theirs to trade. Boon’s brow furrowed. Trade. My husband’s kin. Her voice was flat now. They said I owed them something for marrying their son. When he died, they came to collect.

Told me to sign papers, give over the land claim, told me the babies were theirs, too. Said a woman like me couldn’t raise them alone. Boon’s stomach turned. He didn’t speak. I ran. That’s all I ran. Boon rubbed his jaw. You figure they’ll come back. I know they will. He stood and walked to the window, peering out over the ridge.

Snow had started falling again, soft and slow. He stared at the trail as if trying to memorize every hoof print before the weather erased them. “You said you’d leave,” Boon said. “You still want to.” Ruth didn’t answer right away. “If I go, they’ll find me on the road. If I stay, I put you in danger.” He turned from the window. They’ll come either way. Ruth met his eyes.

Why are you helping me? Boon hesitated, then said simply, “Because someone should have.” The silence after that was not heavy. It was solid, like something had locked into place between them. Not affection. Not yet, but purpose. Shared danger had a way of doing that. That afternoon, Boon hitched his mule and rode down the trail toward the East Fork. He didn’t say where he was going. But Ruth knew it wasn’t for supplies.

Not with the look in his eye. Not with the way he took his rifle this time and the way he pulled his hat low. Ruth stayed behind, tending the fire, boiling water to soak the twins claws. Clara slept more than Seth, who fussed every time Ruth set him down, but she kept her hands moving. Busy hands kept the mind from wandering.

The sun dropped low before Boon returned. He brought no food, no game, no signs of success. Just rode in slow, mule quiet, shoulders tight with tension. Ruth opened the door before he reached it. They’ve doubled back, he said, set up at the trading post, waiting for me. Boon nodded. She swallowed. Then I’ll go tonight. You won’t make it a mile. I’ll try.

Boon stepped forward, blocking the door with his frame. You won’t make it. The moment hung there. Ruth staring up at him, fury and fear twisting behind her tired eyes. She hated being saved. Hated needing it, but hated being hunted more. Boon’s voice softened. We do this together or not at all.

She let out a shaky breath and stepped back inside. That night, Boon slept on the floor near the door, rifle beside him, eyes half closed, but never deep. Ruth kept to the cot with the twins. The fire snapped and spit, and the wind carried the sound of distant hoof beatats more than once, though they never drew close. By morning, Boon was gone again. Ruth woke to the smell of ash and an empty chair.

She stepped outside, shielding her eyes from the low sun. The trail was bare, snow scuffed and windb blown, but no sign of boon. He returned at midday, clothes wet with melted snow, boots thick with mud. He carried something in his hand, a folded piece of paper, yellowed and thin. “Got you names,” he said, handing it to her.

Ruth unfolded it, her breath caught. “Marriage license,” she whispered. Boon nodded. “Wasn’t real. Just cop it from the courthouse. Enough to make them think you’re not alone anymore. Ruth’s hands trembled. Boon. It’s your name now. Ren Fletcher. Don’t need to mean nothing unless you want it to, but if they come back, it might give them pause.

She stared at him, stunned. Boon shifted his weight. It’s not the law they’re chasing. It’s weakness. They see a widow, they see property. They see a wife, they think twice. Ruth said nothing. Boon moved past her into the cabin and began stacking wood near the stove like it was any other day.

Like he hadn’t just offered her his name, his protection, his place in the world. The days blurred after that. Each one started the same, checking the trail, listening for riders, tending the children. Boon taught Ruth how to handle the rifle. not to aim, but to load it, clean it, make it ready. She caught on fast. The widow had grit beneath all that dust. One evening, Clara coughed hard enough to turn her lips blue.

Ruth panicked, rocking her by the hearth, whispering prayers. Boon brewed pine needle tea, wrapped the baby in hot claws, sat up half the night beside her while Ruth wept silently into her shawl. By dawn, Clara was breathing easier. You stayed up,” Ruth whispered. Boon didn’t answer. He just handed her the baby and walked out into the snow.

But that night, something shifted. She sat beside him at the fire instead of across from him. He didn’t move, didn’t speak, just passed her the last piece of dried meat and tore the bread in half. They ate in silence. Then came the storm, a real one. Snow so thick it blinded the windows. Wind that howled like a wild animal.

Boon bolted the door and stuffed blankets into the cracks. Ruth held the twins tight while Boon loaded the rifle and placed it against the wall. Storm won’t keep M out, he said quietly. Ruth nodded, but it might buy us time. And time they’d both learned, was everything. In the heart of that storm, they heard it.

Not a knock this time, but a voice outside calling her name. Ruth Ren, come out, girl. You got what don’t belong to you. Boon stepped to the door, jaw clenched, heart thutting like a drum. And from behind him, Ruth rose. I’ll go, she said. No, Boon replied. Boon. I said no. And then outside, a shot cracked through the night.

The crack of the rifle echoed through the valley, slicing through the storm’s howl like a blade. The cabin shook as the wind roared back in response, and Ruth dropped to the floor, instinct overtaking fear as she covered the twins with her body. Boon didn’t flinch. He was already at the window, peering out from behind the curtain he’d stitched from an old burlap sack. His eyes scanned the tree line, the open slope beyond it, the faint shadows dancing in the snow swirled dark. Nothing moved.

No second shot, no rider charging the porch. No sign of who had fired. They’re trying to spook us, Boon muttered. Flush you out. Ruth looked up from the floor, face pale. Do they know about you? Don’t matter, he said flatly. They know enough. Another gust slammed the cabin, and this time the wind found a crack near the roof line, whistling in like a warning. Boon moved quickly, stuffing a wool scrap into the gap.

The fire hissed as a flurry of snowflakes sneaked through the chimney. “They’ll wait,” he said finally. “Let the storm do their work. When it breaks, they’ll come.” Ruth rose slowly, her arms still curled around the sleeping twins. “Then we leave.” Boon turned and go where? Anywhere that’s not here.

He looked at her hard with two newborns in this weather. She shook her head. You think staying safer? Boon didn’t answer. Not right away. He crossed the room, lifted the rifle again, checked the chamber. Then he knelt by the hearth, and stirred the coals, throwing on another log. The flames leapt, casting long shadows across the walls. Let them come, he said finally. Ruth stared. Boon.

I’ve been running my whole life, he said, voice low. From things with more teeth than these men. If I run now, I’m just giving them what they want. Ruth’s voice cracked, but you didn’t do anything. Boon looked at her. Really? Looked at her. Neither did you. The wind screamed again, but it couldn’t touch what settled between them then. resolve.

Not rage, not vengeance, just quiet bone deep resolve. Ruth moved to the wall, peeled back the quilt Boon had nailed over the shelf, and pulled down a rusted pistol. I can’t shoot straight, she said. You’ll learn, Boon replied. They spent the rest of the night preparing, not in panic, not in chaos, in silence. Measured, focused.

Boon checked the door latches, reinforced them with a spare beam he dragged from behind the shed. Ruth packed what little food they had into a satchel, dried beans, cornmeal, a bit of lard. She wrapped the twins tighter, tucking them into the largest crate and patting it with old coats and a torn pillow. If something happened to her, at least they might stay warm long enough for someone to find them.

if she didn’t say the word aloud, but it throbbed in her chest like a second heartbeat. By dawn, the storm began to fade. Not gone, just pausing like it knew what was coming and wanted to watch. The sky lightened, a sickly gray yellow that made Boon’s shoulders tighten.

He stepped onto the porch, rifle slung across his back, breath fogging out before him. Snow crunched beneath his boots, untouched except for a single set of prints, his own from the day before. No new tracks yet. Back inside, Ruth fed Clara and Seth while watching the window. She kept one hand near the pistol on the table, her fingers trembling only when she exhaled.

Boon paced once, twice, then settled into the rocking chair by the door, where he could see both the ridge and the woman who now shared his name. “Was he good to you?” Boon asked suddenly. “Ruth looked up startled.” “Your husband?” he clarified. She hesitated. “He tried. He was young. Grew up thinking women were supposed to be quiet. I was.

” Boon gave a single nod, then returned his gaze to the ridge. “Did you love him?” he asked. Ruth swallowed enough to grieve, not enough to stay owned by his family after he died. Boon didn’t respond. Just let the words settle like snow on the floorboards. An hour passed, then two. Then came the first rider. Not loud, not fast, just present.

Boon saw him through the trees, a silhouette between trunks, moving slow like a wolf not yet hungry enough to pounce. A second followed, then a third. By the time Boon leaned forward to signal Ruth, five men had taken position in a wide semiircle, just far enough not to be seen clearly. “They’re waiting,” he murmured. “Want me to come out first?” Ruth stood pistol in hand.

“Then we make them come to us.” Boon nodded. Another hour passed. Seth cried once, but Ruth hushed him quickly. Clara slept through it all, her tiny chest rising and falling like she didn’t know the world could be cruel. Boon stepped outside. Not far, just to the porch. Snow crunched again, a different rhythm.

One of the riders broke from the trees and came forward, hands up. It was vain. Hat low, eyes hidden. Boon didn’t raise the rifle. Not yet, just watched. I ain’t here to hurt you, Vain called. Just want what’s owed. Boon’s voice was stone. She don’t owe you a thing. Vain smiled. That ain’t for you to say. She’s my wife, Boon said evenly.

Makes it my business. Vain laughed. You think a paper changes what she took? Boon raised the rifle a half inch. I think it changes what happens if you don’t turn around. Behind Vain, one of the other riders shifted. His hand drifted toward his belt. Boon saw it. So did Ruth. The shot rang out before either could shout. Vain dropped. Boon blinked.

Ruth stood behind him on the porch, pistol still smoking in her hands. Her face was white. Her breath came in gasps. “I saw him reaching,” she said. “I I didn’t mean to.” Boon grabbed the rifle and stepped off the porch. The other riders scattered, two galloped off immediately, snow kicking up in a cloud.

One stayed behind, frozen in place, rifle halfway out of his scabbard. Boon leveled his aim. “Drop it!” The man hesitated, then obeyed. Take him, Boon said, nodding toward Vain’s crumpled body. Tell the rest she’s not alone anymore. The man scrambled to obey, dragging Vain’s body into the snow and lifting him onto the nearest horse with a grunt.

Boon watched them vanish into the trees, then turned back toward the porch. Ruth had sunk to her knees, the pistol still clutched in her lap. Boon knelt beside her. “You saved us,” he said. She shook her head. I killed him. He came to kill you. Her eyes were wide, hollow. I didn’t want to. You didn’t have a choice.

She looked down at the pistol. Feels like I did. Boon took it gently from her hands and set it aside. You’re not that kind of person, he said softly. But the world don’t always let us stay who we were. They sat like that until Seth cried again. Ruth stirred, lifting the baby from the crate with shaking arms. Clara opened her eyes too, blinking in the fire light.

Boon stood and stoked the flames higher. Storms passed, he said, “For now.” Ruth rocked the twins slowly. “They’ll send more.” “Maybe, but you’ll be here,” she whispered. Boon didn’t speak. He didn’t have to. Later that night, when the children were asleep and the sky had turned deep blue above the treetops, Ruth stepped out onto the porch beside him.

She looked out across the snow, the silence, the faint trails of hoof prints disappearing in the dark. “They’ll always think I owe them something,” she said. Boon looked down at her, the fire light casting gold in her hair. “You don’t,” he said. “You owe them nothing.” She turned toward him. Then what do I owe you? Boon shook his head. Nothing. But I’ll keep standing between you and the rest of the world until you believe that. Ruth smiled, but it wasn’t joy.

It was something deeper, relief, a beginning. And somewhere in the quiet of that moment, Boon Fletcher, lonely cowboy, last dollar man, realized he’d given her more than a coin in town that day. He’d given her a place to return to, and maybe, just maybe, a future. But not all storms stay gone, and not all debts stay buried.

Far to the east, in a town that never forgot a name, a letter had been sent, and its arrival would change everything. The letter was stamped with red wax and dust. It bore no return address, only a seal shaped like a ram’s skull, and the faint scent of pipe smoke and pine sap. It reached the sheriff of Mercy Ridge two weeks after the storm broke, delivered by a courier who refused to speak a word and vanished before the ink dried on the signature log.

Sheriff Curt Garvey turned the envelope in his weathered hands twice before slicing it open with the corner of his badge. What he read made his gut go tight. The words were plain, the handwriting practiced, measured like someone who spoke only when it counted. Your town harbors a woman named Ruth Ren. She is not merely a widow.

She is the last living heir to the Ren silver claim, surveyed and recorded in 1869. She fled with forged documents and twin offspring of questionable paternity. We intend to collect what is owed. We do not ask your help. We expect your silence. You will be compensated for your discretion. It was unsigned, but it didn’t need to be. Garvey knew the tone.

He’d heard it in back rooms and behind saloon doors his whole life. Words from men who smiled as they took your name, your land, your blood. He folded the letter slowly, slipped it into the pocket of his vest, and poured himself a drink. Meanwhile, Boon Fletcher swung an ax behind the cabin, sweat cutting through the dirt on his brow.

The snow was mostly gone now, melted into slick patches of mud and grass, and the scent of pine sap floated strong in the air. Spring was trying, clawing its way through frostbitten soil, and in the small clearing where Ruth hung baby linens on a line strung between two trees. It felt for a time like the world had forgiven them. Clara giggled in her basket. Seth chewed on his fist.

Ruth hummed a tune Boon didn’t recognize, but the sound settled in his bones like something he’d known all his life. They had made it through the storm. The men had ridden off. The knock had not returned, for now they lived. But Boon had learned long ago that peace, like fire, only burned as long as you fed it, and they were running out of wood.

That evening, while Ruth mashed wild potatoes and Clara banged a wooden spoon against the floor, Boon returned from the creek with a rabbit over his shoulder and a frown carved deep across his face. “Town’s talking,” he said as he stepped inside, placing the rabbit on the table with a dull thud. Ruth looked up about us, about the letter. She went still.

Boon cleaned the rabbit in silence. the knife moving with practiced rhythm. When he finished, he rinsed his hands and leaned against the counter. “It wasn’t just about the land,” he said. “Wasn’t even about the children.” Ruth met his gaze. “They want you because you’re the last piece of a claim they don’t want made public.

” She looked away, jaw tightening. “I never wanted that land. They don’t care what you want.” A long silence passed. Finally, Ruth whispered. It was supposed to be for him, for our family. Daniel thought it would save us. We were going to build a chapel on it, put up a school. He had a dream. They didn’t want that. They wanted silver without charity, wealth without witness.

Boon nodded, so they buried him. She didn’t respond. Just reach for Seth and held him close. We can go, she said. Still time. Head west, Oregon, Washington territory. I heard there’s work in the mills. Boon shook his head. They’d follow. Men like that always do. And out there we’d be strangers. No one would know your story.

No one would care. Then what do we do? We make them care. Ruth’s brow furrowed. What does that mean? It means we fight back. Not with guns, with truth. She blinked. You want to make it public? Boon nodded. We tell the right person. We let them know you’re not running anymore.

And you think they’ll care? I think they might. The next morning, Boon rode into Mercy Ridge alone, wearing a clean shirt and the only pair of boots without a tear across the sole. He stopped in front of the telegraph office and dismounted slowly. Inside, the clerk looked up from his ledger with a frown. Morning.

Boon said, “I need to send a message to who?” Boon pulled a slip of paper from his coat to Judge Laram in Carson City. The clerk squinted, “That’s Nevada.” Boon nodded. “That’s where the truth lives.” The message was short. Ruth Ren is alive. Widow of Daniel Ren. She has the land documents, proof of inheritance. Silver claim is hers. Enemies seek to erase her. Come if you still believe in justice.

Boon paid the last coin he had, a nickel he’d found behind the stove the week before, and stepped back outside. By the time he returned to the cabin, Ruth was pacing. Did it go through? It went through. She stared at him. Now what? Now we wait. But it didn’t take long. Four days later, a rider appeared on the ridge.

This one was alone, but different. Dressed in black with silver trim, his coat long and trailworn. He carried no rifle, just a satchel across his chest and a badge at his hip, one with the seal of the Nevada High Court. Judge Laram. He stepped down from his horse and approached the cabin like a preacher entering a battlefield. Boon met him at the door.

I got your wire,” the judge said. Boon nodded. “She’s inside.” Laramie entered quietly, removing his hat. When Ruth saw him, her breath caught. She stood, the twins asleep in a crate beside her. “I knew your husband,” the judge said. “He came to me once, said he was scared for you, that the people around you weren’t to be trusted.” Ruth swallowed.

He said he could handle it. He was wrong. She nodded, eyes glassy. Laramie stepped forward and offered a small folded document. I brought the certified records. The land was never properly transferred. It’s still in your name. Her hand trembled as she took it. But you need to come with me, the judge said. Sign it publicly in Carson City in front of witnesses. Ruth hesitated.

And if I do, they’ll bury you with silence. She looked at Boon, then at the twins, then back at the judge. Then we go, she said, but not alone. Boon stepped beside her. You sure about this? He asked. I’m tired of running. Then I’ll ride with you. 3 days later, they set out. Ruth, Boon, the twins in a basket strapped to the back of the judge’s horse.

The ride was long, slow, dangerous in places, but no one came after them. Not yet. It wasn’t until they reached the final ridge before Carson City that they saw the smoke. Not campfire smoke. Buildings, the courthouse burning, Boon’s jaw tightened. The judge spurred his horse forward, Ruth clutching the basket tight. By the time they reached the town, the square was chaos.

Fire crews doused embers, citizens cried out, and the courthouse lay in ruins. “Message received,” Boon muttered. “They’re here,” the judge said grimly. “Ruth stepped off the horse, hair in her face, dust in her mouth, the baby stirring from the commotion. We go somewhere else,” she said. “No,” Boon said. “We stand here. Let the world see.

From across the square, a man emerged from the crowd. Ruth froze. It wasn’t one of the writers. It was worse. Her husband’s brother. Martin Ren. Tall, sharp, cold as the minds he’d inherited by blood, but not by law. He smiled like a man already victorious. “Didn’t expect to see you alive,” he said. Ruth stepped forward disappointed.

“Concerned,” he said smoothly. “You’re causing trouble confusing the law.” “I am the law,” Judge Laram snapped. “And she’s under my protection.” Martin didn’t even look at him. “This isn’t about papers. It’s about legacy. My brother made choices, poor ones, and now his widow’s trying to cash in.

” “She’s trying to survive,” Boon said, stepping beside her. Martin eyed Boon with contempt. And who are you? The man who will put you on your back if you don’t leave. Martin chuckled. This town won’t stand for her. Ruth’s voice rang out stronger than anyone expected. Then I’ll make them. She turned, raised the folded documents high, and shouted.

This land was mine. My husband died trying to do good. And I won’t be buried with him just because I refused to be sold. People stopped, faces turned, whispers rose. The fire still smoldered, but the heat now came from the crowd. Not rage, hoping. It spread like smoke. Martin saw it, felt it, and for the first time, his smile slipped.

Boon placed a hand on Ruth’s shoulder. She didn’t flinch. And somewhere in the sky above, a raven cried out. A storm was coming again. But this time, they were ready. The town square of Carson City didn’t fall silent. Not exactly. But the noise shifted, moved. Ruth’s voice had cracked something open, and now it echoed through the fractured square like a bell rung too close to the soul.

She stood in the ash thick air, twins bundled against her chest, the fire’s orange glow still licking the bones of the courthouse behind her. She didn’t blink as Martin Ren glared at her with all the rage of a man who just lost something he thought the world owed him. Boon stood a step behind her, shoulders squared, eyes fixed not on Martin but on the gathering crowd.

farmers, tradesmen, miners, wives, school boys. Some held buckets, others their children, but all stared at Ruth now like they didn’t know what to make of her. A widow, a mother, a thief, a hero. Boon leaned in close enough for Ruth to hear without turning. They’re listening. Ruth adjusted Clara and Seth in her arms, her voice steady despite the tremble in her knees.

“You burned the courthouse,” she said flatly, eyes locked on Martin. You destroyed the records. Martin’s smile twitched, not with humor, but with that familiar, brittle confidence of men who thought money could erase truth. You can’t prove that, he said. I don’t have to, she replied. You just proved everything else.

Behind them, Judge Laram stepped forward, holding what remained of the legal documents, the burnt edges still warm in his hand. You’re not the first man to try and rewrite history with ash, the judge said. But the land claims exist in more than one place. I’ve sent copies to Sacramento, San Francisco, even Denver. His eyes narrowed. You’ve made this public now.

Martin’s face pald for just a moment, just enough for Boon to see the crack beneath the polish. You think people will believe her? Martin asked, turning to the crowd. some woman who wandered into town with forged papers and a fake husband. Boon’s voice dropped into the space between words like a stone. I married her. Several heads turned.

Ruth’s breath caught, but she didn’t correct him. She took my name, Boon continued. Not to steal, to survive. I’ve watched her walk through fire with two newborns and no help. If you think she’s lying, ask yourself why a man like me would stand beside her. No one answered, but they didn’t turn away either.

Martin’s mouth twisted, and for a second, Boon thought he’d lunge, but the crowd was too thick now, too uncertain. One wrong move and he’d tip the balance in Ruth’s favor. He knew it. “I’ll see you in court,” Martin spat, turning on his heel. “No,” Judge Laramie said sharply. “You’ll wait for the summons. You’re not above this. Martin didn’t reply. He disappeared into the crowd like smoke into wind.

Ruth staggered slightly, the weight of the children pulling at her arms, the rush of adrenaline draining from her limbs. Boon stepped beside her, took one of the twins, and wrapped an arm around her back. The judge gestured toward the hotel. “You’ll stay under my protection until the hearing.” Ruth nodded. “Thank you.” That night, the hotel gave them two adjoining rooms.

Boon took the cot by the window. Ruth curled up in the bed with the twins, who slept as if the world hadn’t nearly split open hours before. Outside, the town buzzed low with murmurss and shifting eyes. Stories were being written in candle light and whispered through cracked windows.

Inside, Ruth lay awake long after the children had settled, staring at the ceiling like it might collapse at any second. “I was never meant to do this alone,” she whispered. Boon, still dressed, sat by the window, cleaning his rifle. “You’re not.” She rolled onto her side, voice softer. “You meant it what you said.” He didn’t look up. About what? About marrying me.

Boon wiped the barrel with a rag. thoughtful. I meant what I could. I meant standing beside you. I meant not letting the world eat you alive. She nodded. I don’t expect promises, just truth. That’s all I got, he said. And it was enough. In the morning, they were called to the town hall, the only standing building large enough to hold a hearing now that the courthouse was gone.

The judge set up a makeshift bench. Word had spread. More people came than anyone expected. Ranchers, miners, a traveling pastor, half the town pressed into the room, some standing on crates to see. Martin Ren arrived flanked by two lawyers and an older man with silver spectacles and a scar across his cheek.

A banker by the look of him. His gaze never left Ruth, and she knew instantly that he was the one who had sent the first letter, the man who’ thought she could be erased with ink and fear. The proceedings began. Judge Laram recounted Ruth’s claim, her marriage to Daniel Ren, the land survey filed under her name, the threats, the flight, the letter.

Martin’s lawyers pushed hard, questioned the validity of the documents, challenged the authenticity of her name change, even tried to claim Boone had lied under oath. But Boon didn’t flinch. He sat straight, answered every question plainly, and when asked what he stood to gain from protecting Ruth, he replied, “Nothing, and that’s why I did it.” Ruth’s testimony came last.

She held nothing back. Told the court about Daniel, about the dream, the school, the chapel, how he died with her name on his lips and the deed sewn into the lining of his coat, how she’d walked across snow with two infants and no one but God to witness. And when they asked if she believed the land still belonged to her, she said, “No, I don’t believe it.

I know it because he gave it to me. And no one, not fire, not blood, not men in suits, can take that away. When she finished, the room was silent. Not a word. The judge didn’t rush. He stood, stepped down from the bench, and looked each party in the eye before declaring. The claim stands.

Ruth Ren Fletcher is the rightful heir. Gasps rippled through the crowd. Someone clapped, then another. It spread slowly at first, then like thunder. A sound not of triumph, but of recognition. Martin Ren turned red. The banker’s jaw tightened, but neither moved. Not yet. Afterward, on the hotel balcony, Ruth held Clara against her chest while Boon leaned on the rail beside her, watching the sunset over the distant ridge line.

“They’ll come again,” she said softly. “They’ll appeal. They’ll fight.” Boon nodded. “Probably.” and I’ll fight back,” she added. He looked at her. She met his gaze and something passed between them. “Not relief, not victory, something older, like the ground shifting beneath you, not to break, but to settle.

” Clara gurgled, her tiny hands waving in the wind. Seth stirred in the cradle inside the room. Boon took Ruth’s hand. She led him. Neither said a word, but both knew this was only the beginning. Because men like Martin Ren didn’t disappear. They regrouped. And far beyond the edge of town, a message was being sent to someone worse. Someone Ruth had tried hard to forget.

The man who received the message didn’t read it right away. He let it sit on the windowsill of his office, sunlight warming the envelope as dust settled on its edges. Outside the high desert rolled out in gold and sage brush, but inside everything stood still, still as death.

The man sat at a desk that was too clean, too polished, and when he finally reached for the letter, his fingers moved like they were used to breaking things. He broke the seal. “Read the note, then folded it once carefully.” “She’s alive,” he said aloud. The room was empty except for a clerk sitting on a stool by the door. The clerk’s pen scratched to a halt.

He looked up pale, “Sir.” The man Henry Clay Ren stood. Get the horses ready and wake the marsh boys. We ride at dusk. Sir, that’s three states away. Clay Ren turned slowly, his eyes the color of river ice. Then we best not sleep. Boon Fletcher knew that men like Martin didn’t fight alone.

He also knew when a man like Martin disappeared without a fuss, it meant something worse was coming. So when Ruth suggested they stay in Carson City a few more days just to breathe, Boon agreed. But he didn’t sleep deep. Not after the hearing, not after the applause. He’d seen this pattern before. Hope then silence then fire.

On the fourth night, while Ruth rocked Seth by the window and Clara slept in Boon’s arms, the sheriff knocked. “Boon opened the door to find Curt Garvey standing with his hat in hand, and a look like he just swallowed something bitter. “You got trouble coming,” the sheriff said. Boon stepped aside. Garvey entered and closed the door behind him. They sent word out of Nevada Junction.

Three riders crossed over last night fast. Didn’t stop to rest. Just watered their horses and rode west. Ruth stood slowly. Ren men. Garvey nodded. One of them’s Henry Clay Ren. He’s bloodin to Daniel’s father. Owns half the mines out east. Not just silver. He trades in people, too. Word is when he wants something, he gets it. Boon’s jaw clenched.

How long? Two days, maybe less. Depends how hard they ride. Boon looked at Ruth. She was already packing. They didn’t run. Not this time. But they moved. 3 hours later, they were on the trail west. Boon, Ruth, the twins bundled tight, and Sheriff Garvey trailing close behind with a mule cart full of supplies. The judge had done what he could.

sent telegrams ahead, signed temporary warrants, but it was clear the law would not stop Henry Clay Ren. I need to see it, Ruth said the next morning as they rode beneath the ridge, the land. Boon nodded. You will. It took another day to reach the edge of what once belonged to her husband.

It was a high slope above a creek, dotted with ash trees, and split by a ravine so narrow you could leap it. Daniel had walked this land years ago with stars in his eyes and a map in his hand. Now it was nothing but wind and silence, but it was hers. They made camp on the northern ridge just below a cops of twisted cedar. Boon built a fire low and tight.

Ruth laid the babies on a folded quilt. The sheriff sat with his back to a rock rifle across his lap. And then came the sound Boon had feared since the courthouse burned. Horses not fast this time. Measured deliberate like men who didn’t need to chase what they already owned. Boon rose and stepped forward, squinting into the dusk.

Three riders, all in black. The man in front didn’t wear a hat. His silver hair was sllicked back and his face held the stillness of a grave. Boon didn’t need to ask. “Henry Clay Ren,” he muttered. Ruth stood behind him, rifle in her arms, hands trembling only slightly. Clay dismounted without a word, his boots crunched across the gravel as he approached. “You’ve made a mess,” he said not unkindly. All this noise.

I was content to let you disappear, but then you took your husband’s name and dragged it through a courtroom. Ruth stepped forward. It’s my name. You just buried it when you couldn’t control me. Klay’s eyes narrowed. Your husband didn’t understand what he’d married. He was a dreamer. You were always going to ruin him.

Boon growled low and dangerous. Careful. Clay didn’t blink. I’ve buried men tougher than you, son. And I’ve outlived men richer than you. For the first time, Clay smiled. Not kindly, just curiously. You think this ends here? He asked. Out in the dust without an audience. I don’t care about the audience, Ruth said. Only the truth. Klay stepped closer. Too close. Boon raised the rifle.

You’re not taking her, he said. I don’t want her, Klay replied. I want the land. Give me the deed. I’ll give you peace, refuge, and I’ll take it the way we always have by waiting, by starving you out, by turning the town’s folk against you. There’s more than one way to erase someone, Mrs. Fletcher. Ruth didn’t move. She reached into her satchel, pulled out a folded paper, the original deed, and held it up.

Clay’s eyes lit with triumph. Then she dropped it into the fire. He lunged. Too late. The flames swallowed the paper before his boot hit the stones. Boon raised the rifle. Garvey stood. One of the Ren riders reached for his gun and dropped instantly as the sheriff fired. Chaos erupted. Boon tackled Clay before he could draw. They hit the ground hard.

Dust rose. Ruth screamed. The second rider fired and missed. Boon punched Clay square across the jaw, blood blooming from the older man’s lip. Garvey’s second shot dropped the other rider. Klay scrambled, wheezing blood on his teeth. Boon stood over him. “Go home,” he said. “Or don’t, but you’re done here.” Klay spat blood. You think you’ve won. Boon looked down at him.

I know what winning looks like. It’s a fire that doesn’t go out when men like you show up. Clay coughed. You burn the deed. Ruth stepped forward. I don’t need it. I am the deed. She turned away, lifted Seth from the quilt, then Clara. The children blinked unharmed, unaware. Garvey tied Clay’s hands, hauled him up.

You’ll stand trial, the sheriff said, for threatening a mother for attempted theft, for conspiracy. I’ll make sure of it. Clay didn’t fight, not because he was beaten, but because something colder settled in his eyes. “This ain’t over,” he said. Ruth walked past him, boots crunching calmly in the gravel. “It is for me,” she said. “I’ve got better things to build now.

” They rode back to town with clay in chains and the sun rising behind them. The people of Carson City didn’t cheer. They didn’t line the streets, but they watched and that was enough. At the cabin two weeks later, Ruth’s cabin now with a new roof and a garden just beginning to breathe green.

Boon stood by the fence as Ruth rocked Clara beneath the porch’s shade. “Would you do it again?” she asked softly. Boon nodded every time. Ruth smiled, even the part where I burned the deed. He laughed deep and real, especially that part. They sat in the quiet, watching the wind move the trees. The land was still scarred, still raw. But it was theirs for now until the next fight, and the one after.

But Boon knew something now. They wouldn’t be fighting alone. The morning air was thick with the scent of damp earth and pine as Boone Fletcher pushed the barn door open and stepped into the rising light. His boots were coated in mud from a midnight rain, and he could hear the distant coup of mourning doves in the cedars beyond the pasture.

The land was quiet now, not in that dangerous waiting sort of way, but the kind that feels earned, hard one, honest. It had been 3 months since the last Ren rode west with shackles on his wrists and curses in his throat. The trial had been short, federal court, not local. The judge from Reno made it clear. Henry Clay Ren would not return to Nevada soil as a free man again.

The men he brought with him, the paper trail of bribery, the burned courthouse, it was all too much even for a name like Ren. The family’s hold had cracked, and though the silver mine still ran, their grip on the towns that surrounded them had slipped. Ruth never spoke of the verdict. She hadn’t needed to. The way she rose each day, fed her children, worked the soil, touched Boon’s arm as he passed, those were her victories.

She didn’t measure justice in speeches or headlines. She measured it in peace. and peace had finally settled over their little ridge. Boon walked the fence line, tightening a loose post and scattering the last of the winter straw from the feed bucket. The new calf, just born last week, balled from the other end of the paddic.

He smiled, not because life was easy, but because it was simple again, clean. From the cabin porch, Ruth called out. Her voice was calm, warm, different than it used to be. Not lighter, but more filled in, like the hollow places had begun to grow something. Boon. He looked up. What is it? Mail came. He frowned. Mail. She held up a folded envelope from the courthouse, the real one this time.

Boon dusted off his hands and walked back up the slope, his heart beating slower now than it had for months. Each step toward her felt like coming home all over again. Ruth handed him the letter, eyes searching his face. Boon opened it slowly, carefully. Inside was a single sheet, typewritten official.

It declared that Ruth Ren Fletcher was now, without contest, the lawful holder of the Western Nevada Mineral Rights for Parcel 167B and the adjoining claim territory. The signature was clean. The stamp was real. Boon handed it back to her without a word. Ruth folded it gently and placed it inside her apron. “You’re rich now,” he said. She snorted. “I was rich the day I survived the snow with two babies and found a cabin with a fire still burning.” “He didn’t argue.

” They sat on the porch together as the sun stretched long shadows across the hills. Clara played at their feet with a wooden spoon and a broken horseshoe. Seth toddled after a chicken near the water trough, laughing every time it squawkked and fled. Ruth leaned her head on Boon’s shoulder. They’ll come again. You know that, right? Boon nodded. Let them.

I’m not afraid anymore. You shouldn’t be. A long silence passed, broken only by wind and the occasional cry from the coupe. Then Ruth spoke again, her voice low. I never thought I’d make it this far. When Daniel died, I thought that was the end of everything. Not just my marriage, but myself, like I’d been buried next to him.

Boon turned to look at her, but she kept her eyes forward. And then I knocked on a stranger’s door, she whispered, and the stranger opened it. He smiled faintly. I thought I was just buying someone dinner. You were buying me time,” she said. “Time enough to make a different choice.” The sun crept toward the horizon. Boon stood and walked down the steps, then turned and offered his hand.

She looked up, curious. “Come see something.” She took his hand and followed. He led her past the barn, through the orchard, just starting to bloom. Beyond that was a stretch of land still untouched. No crops, no fencing, just earth. Boon stopped beside a flagged post sticking from the soil. What’s this? She asked. I started clearing it last week. For what? He turned to her, eyes steady.

The school Daniel wanted. Ruth’s lips parted, but no sound came. I’ve got wood ordered. Paid for it with the last of my savings. Should be here by next month. She blinked back tears. Boon, you don’t. I do, he said. It was his dream, but now it’s yours, too. And I figure the kids out here deserve something better than dust and silence.

Her hands trembled as she touched the post. “They do,” she whispered. “Figured you’d be the one to run it,” he said. “You’ve taught me more in 3 months than I learned in 20 years.” Ruth laughed then, real and full. It broke whatever damn it had held her quiet all day. She stepped forward and kissed him, not quickly, not shyly, with the certainty of a woman who had crossed death, winter, courtrooms, and fire to find herself again.

Boon didn’t speak, didn’t need to. They stood together in the twilight, the wind brushing past like a benediction. The ghosts that once haunted them now quieter, distant. Later that night, Boon rocked Seth to sleep while Ruth menied a torn hem on Clara’s blanket. The lantern burned low. The fire crackled. Outside, the coyotes yipped, but no hoof beatats followed.

In the cradle of that silence, Ruth whispered. “Boon!” “Yeah, I want to marry you.” He turned, eyebrows raised. “For real this time,” she added. “Not for paper, not for protection. Boon didn’t answer at first. He just walked to her, knelt beside the chair, and pressed his forehead to her knee. Been waiting to hear that since the knock on my door. She ran her fingers through his hair.

And the silence between them became something new. Not the echo of fear, but the space where love grows. The schoolhouse took five months to build. The first students came on horseback, two by wagon, one barefoot with her baby brother in tow. Ruth taught them letters and numbers, but also how to speak without shame, how to stand without fear.

She told them about silver and storms, and how sometimes surviving was the bravest lesson of all. Boon built benches, repaired roofs, traded feed for pencils. On the wall, Ruth hung a picture of Daniel. not to replace Boon, but to honor the man who’d begun the dream.

Above it, carved into a wooden sign, were words the children had chosen themselves. A place for the brave. Years passed. Clara and Seth grew. Boon and Ruth stayed. Some winters were cruel, some summers dry. The Ren name was never fully forgotten, but in time it became just another chapter in the long, painful history of the frontier. And every time someone knocked at the door of the Fletcher homestead, be it a lost traveler, a pregnant girl, or a boy looking for work, Ruth answered.

Because she remembered what it meant to knock with nothing left but hope. And Boon always made sure the fire was lit, just in case.