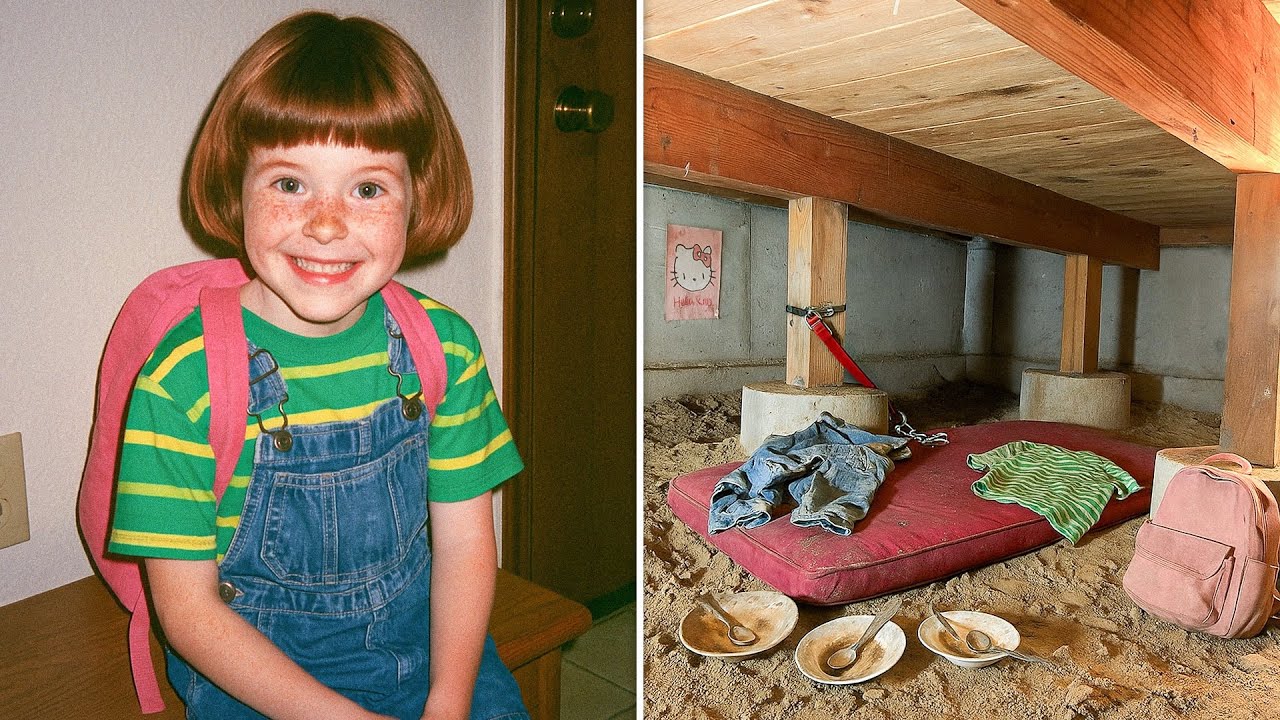

A six-year-old girl from a suburban town in America set off for school one ordinary morning and simply disappeared into thin air. She had less than a 5-minute walk ahead just two blocks through streets she’d traveled countless times. But this time she would never reach the school doors. Then 8 years later, electricians working beneath an old property discover items that revealed the devastating truth about where Lily Whitfield had really gone.

The stack of overdue bills blurred before Norah Whitfield’s eyes as she sat at her kitchen table, the morning coffee growing cold in her chipped mug. 8 years had passed since Lily disappeared, but the financial strain of private investigators, age progression specialists, and maintaining websites had never eased.

She mechanically sorted the envelopes, electric, water, another credit card statement, when her phone buzzed against the worn wood surface, displaying an unknown local number. Mrs. Whitfield, this is Detective Martinez with the County Sheriff’s Department. The voice was professional, but carried an undertone that made her grip the phone tighter. I need to speak with you about your daughter’s case.

Her heart hammered against her ribs. After 8 years, calls about Lily came less frequently, usually dead ends or cruel pranks. Have you found something? Ma’am, I’d rather discuss this in person, but given the circumstances, electricians working on an abandoned property discovered some items we believe may belong to your daughter.

The room tilted. Norah’s free hand fumbled for a pen, knocking over the salt shaker. Where? What did they find? The property is on Willow Creek Road about 15 miles outside town. The house was scheduled for demolition and the crew was checking the electrical systems when they accessed the crawl space.

He paused and she could hear papers rustling. Mrs. Whitfield, they found clothing and personal items that match the description of what Lily was wearing when she disappeared. Her hand shook violently as she scrolled the address on the back of an electric bill. 15 mi. The original search had covered a 5m radius from the school, expanding to 10 mi over the following weeks.

They’d never gone as far as Willow Creek Road. It had seemed impossibly far for a six-year-old to travel. “I’m heading there now,” she said, already standing. “Mrs. Whitfield, I need to prepare you. What we found? It’s disturbing. The scene suggests. I’m coming. She hung up before he could finish, grabbing her keys and purse in one motion. The drive stretched endlessly despite her speed.

The route took her past familiar landmarks, the elementary school, the old water tower, the church where they’d held vigils before venturing into areas she’d rarely traveled. The landscape shifted from suburban streets to rural farmland, then to stretches of undeveloped woodland.

Her GPS counted down the miles as her mind raced through possibilities, each more terrible than the last. Willow Creek Road was barely more than a dirt track winding through dense trees. She nearly missed the cluster of police vehicles until she saw the crime scene tape stretched between two oak trees. The house itself squatted like a wounded animal behind overgrown hedges, a singlestory ranch with rotting siding, a partially collapsed front porch, and windows either broken or boarded over.

Weeds had consumed what might once have been a lawn. Detective Martinez met her at the perimeter. He was younger than she’d expected, with kind eyes that held the weight of what he’d seen. Mrs. Whitfield, thank you for coming. I want to walk you through what we’ve found, but I need you to understand this is an active crime scene.

Just show me, she said, surprised by the steadiness of her own voice. He led her along a path marked by evidence flags circling to the side of the house. The original foundation showed signs of settling, creating gaps between the concrete blocks.

Near the back corner, a wooden access panel lay propped against the wall, revealing a dark opening barely 2 ft high. “The electricians needed to access the main junction box,” Martinez explained, gesturing to the opening. “It’s in the crawl space.” When they went in, he produced a tablet, swiping to crime scene photos. “I can show you these first, or you can see the actual scene. Either way, it’s difficult.

” I need to see it,” Norah said. Martinez handed her protective booties and latex gloves. The forensics team has processed most of it, but we’re still maintaining scene integrity. He crouched by the opening. Powerful LED work lights illuminating the space beyond. “Follow me, and try not to touch anything.” The crawl space smelled of old earth and something else, a mustiness that spoke of long disuse.

Norah had to duckwalk, following Martinez’s flashlight beam across hardpacked dirt. The space extended about 12 ft before reaching what looked like a deliberate clearing. Then she saw it. A filthy red mattress lay on the ground, child-sized, its fabric stained with dirt and other substances she didn’t want to identify.

Attached to the nearest support post, a heavy chain ended in an open padlock, the metal still gleaming despite surface rust. On the concrete block wall, secured with yellowing tape, hung a Hello Kitty poster. The edges curled, colors faded, but unmistakably the same style Lily had loved. But it was the clothes that broke her.

Scattered across the mattress like discarded dolls clothing were Lily’s denim overalls, the ones with the embroidered sunflower on the front pocket that Norah had sewn herself. The green and yellow striped shirt lay beside them. The fabric somehow preserved in the dry environment. The pink backpack slumped in the corner, its cartoon character decoration still visible beneath the grime. “Oh god,” Norah whispered, her knees hitting the dirt.

“Oh god, she was here.” “There’s more,” Martinez said gently. He directed his light to two ceramic plates stacked near the mattress, remnants of food petrified on their surfaces. A plastic water bottle, child-sized, lay on its side. We found DNA evidence throughout the space, hair samples, fingerprints on the plates and bottle. The lab is running everything now.

How long? The question came out strangled. Based on the wear patterns on the mattress and the accumulated debris, forensics estimates extended occupation weeks, possibly months. He paused, choosing his words carefully. Mrs. Whitfield. We’ve also found evidence throughout the main house. Whoever held your daughter here had full access to the property.

Norah reached toward the striped shirt, stopping just short of touching it. She’d ironed that shirt the night before Lily disappeared using the lavender water her daughter loved. Some part of her mind registered Martinez explaining about the preservation conditions, how the crawl space’s consistent temperature and low humidity had prevented decay.

But mostly she just stared at the small clothes that had once held her baby. Who owned this place? She asked finally. Frank Morrison, age 78. He’s been in assisted living for 2 years. The property was rented through a now defunct management company called Riverside Realy.

They went out of business 5 years ago, but we’re tracking down their records. And the renter? Martinez’s expression darkened. Morrison says it was a long-term lease paid in cash. He met the tenant only once during the initial showing, described him as ordinary, quiet, kept talking about needing storage space.

The rent came in cash-filled envelopes, always on time, so Morrison never had reason to visit. Outside the crawl space, Nora noticed a faded sign partially hidden by Virginia Creeper. Riverside realy for lease. The phone number was too weathered to read. We’re going through everything. Martinez assured her. The state crime lab is sending additional technicians. If there’s any evidence that leads to who did this, we’ll find it.

Norah looked back at the house, its blank windows reflecting the afternoon sun. Somewhere in those empty rooms, her daughter had been held. While she’d been printing flyers and organizing searches, while the community had combed through forests and dragged ponds, Lily had been here 15 miles away, invisible.

The rental payments, she said suddenly. There must be records of the rental payments. We’re already on it. Morrison’s nephew is searching through his uncle’s papers. The property management company’s records were supposed to be transferred to another firm, but Martinez shrugged helplessly. Paper records from 8 years ago aren’t always carefully preserved.

As they walked back to the vehicles, Norah memorized every detail of the property. The rusted mailbox, the gravel driveway, the stand of birch trees that would have bloomed white in spring. Lily would have seen those trees through whatever windows weren’t boarded over.

Had she watched them change with the seasons? Had she counted their leaves as a way to pass time? “What happens now?” she asked. “We process every inch of this property. We track down every lead from the rental records and Mrs. Whitfield.” Dot dot dot. Martinez met her eyes. We don’t stop until we find who did this. Leaving the crime scene, Norah intended to drive straight home, but her hands seemed to have their own memory.

Without conscious thought, she found herself turning onto Maple Street, following the route that had been seared into her mind 8 years ago. The old neighborhood looked both familiar and foreign, trees grown taller, houses repainted, driveways repaved. Where her small rental house once stood, a modern duplex now crowded the lot, its beige siding and twin garage doors erasing all traces of the home where Lily had eaten her Cheerios that last morning. She parked at the curb and sat for a moment, gripping the steering wheel. How

many times had she made this drive in those first desperate weeks? 50? 100? each time hoping to spot something missed, some clue that would lead to her daughter. Now knowing Lily had been held captive while everyone searched, the familiar street felt like a mockery.

Norah stepped out and began walking the route, Lily would have taken two blocks. That’s all it had been. A 5-minute walk for a six-year-old short legs. She passed the Henderson’s house where Max, the golden retriever, used to bark hello through the fence. The fence was gone now, replaced by a low hedge.

The big maple tree, where Lily liked to collect helicopter seeds, had been cut down, leaving only a two smooth patch of lawn. At the intersection of Maple and Third, she stopped. The crossing guard post still stood, its octagonal stop sign now automated with flashing LED lights. No need for a human presence anymore. Technology had replaced Harold Walsh’s watchful eyes and warm smile.

The morning sun cast the same shadows it would have eight years ago, and Norah could almost see him there in his fluorescent vest, one hand holding the stop sign, the other waving children across. Harold had been there every morning for over a decade, she remembered.

He knew every child’s name, asked about soccer games and spelling tests, kept a pocket full of stickers for kindergarteners brave enough to cross without their parents. The intersection felt hollow without him. At the corner, a small memorial marker caught her eye. The bronze plaque was weathered but clean, surrounded by fresh maragolds.

In memory of Lily Whitfield, forever six years old, a laminated card tucked among the flowers bore familiar handwriting. Still praying for answers, Mrs. Chen. Norah’s throat tightened. Even after 8 years, the old neighbor maintained the small shrine. She touched the marker gently, remembering how Harold had been inconsolable when he learned about Lily’s disappearance.

He’d blamed himself terribly for having that doctor’s appointment, convinced that if he’d been at his post, Lily would have made it safely to school. For months afterward, he’d organized weekend search parties, printed flyers with his own money, walked through woods and fields, calling her name until his voice grew.

At the one-year memorial service, he’d wept openly, apologizing to Nora over and over for not being there. The weight of the morning’s discoveries pressed down on her. While Harold was organizing searches, while the whole community was looking, Lily had been trapped in that crawl space, 15 mi away, close enough to hear the search helicopters, perhaps, but impossibly far from help.

Norah turned from the memorial and continued toward the school. The route took her past the police station where she’d spent so many hours first giving statements, then reviewing security footage, then simply haunting the lobby for updates. Past St. Andrews Church, where Father Martinez had held special prayer services every week for 6 months.

Past Riverside Park, where volunteers had walked in grid formations, checking every bush, every culvert, every hidden space, except apparently the one that mattered. The elementary school appeared unchanged as she pulled into the visitor parking area. The same cheerful yellow paint, though perhaps a bit more faded. The same playground equipment where Lily had loved the spiral slide.

The same flag pole where they’d lowered the flag to half staff for a week after the disappearance. The bike racks stood empty in the afternoon sun. The same racks where Lily would have locked her bike when she was older if she’d had the chance to grow older. here. Norah sat in her car for a moment, gathering strength.

Inside that building were people who might remember that terrible morning, who might have some forgotten detail that could help make sense of what happened. She needed to know who else had left, who might have had reason to harm a child. The crawl space discovery had opened new questions that demanded answers. The elementary school’s main entrance still featured the same heavy wooden doors. though they now required a buzzer for entry.

Norah pressed the button and identified herself to the secretary, hearing the electronic lock click open. The hallway smelled exactly as she remembered. Floor wax, cafeteria food, and that indefinable scent of childhood energy. Her footsteps echoed on the polished lenolium as she made her way to the main office.

A young woman emerged from the principal’s office, extending her hand with a professional smile that softened when she recognized Norah’s name. Mrs. Whitfield, I’m Dr. Sarah Coleman. I’ve been expecting someone might come by after this morning’s news. Please come in. Dr. Coleman couldn’t have been older than 35 with neat auburn hair and kind eyes behind stylish glasses. Her office was organized but welcoming.

children’s artwork decorating one wall, a small zen garden on the windowsill. I want you to know, she began, settling behind her desk, that although I’ve only been here 3 years, I’m very familiar with Lily’s case. Her memorial plaque in the hallway ensures we never forget.

You weren’t here when Norah let the sentence trail off. No, I took over when Principal Morrison retired, but I’ve read all the files, and the staff who were here have shared their memories. It affected everyone deeply. She turned to her computer. I understand you might want to know about staff members from that time. I can access our employment records. The district digitized everything 5 years ago.

Her fingers flew across the keyboard, pulling up spreadsheets and personnel files. This might be helpful. I’m showing 12 employees who left within two years of Lily’s disappearance. She angled the monitor so Nora could see. Three teachers took early retirement. Mrs. Gonzalez, Mr. Peterson, and Miss Kumar. Two transferred to other districts.

The art teacher, Miss Williams, went to Riverside Elementary and Coach Bradley moved to the middle school. The head janitor, Carl Brennan, left after a background check revealed an old assault charge the district had somehow missed initially. Norah leaned forward. An assault charge from his 20s. Apparently, a bar fight that got out of hand.

It should have shown up in his initial screening, but there was some confusion with his records. When it came to light during a routine recheck, the district had to let him go. Dr. Coleman scrolled further. Two cafeteria workers moved out of state. The Jennings sisters. They were twins. Our music teacher, Mr. Yamazaki passed away from cancer about 18 months after after the incident and Harold Walsh retired from his crossing guard position 13 months ago.

“That’s a lot of people leaving,” Norah observed. Dr. Coleman nodded thoughtfully. “It was an unusually high turnover rate. The trauma of losing a student, especially under such circumstances, it takes a toll on everyone. Some people just couldn’t face coming back to work every day.” A knock on the door interrupted them. An older woman peered in, gray-haired, wearing a cardigan despite the warm weather, with reading glasses on a beaded chain.

“Dr. Coleman,” I heard. Oh my goodness, Nora. Mrs. Fitzgerald, Norah said, recognizing the longtime secretary. Elellanar, please join us, Dr. Coleman said. Mrs. Fitzgerald has been here for 22 years. She knew Lily well. Eleanor Fitzgerald entered, her eyes already misting. Oh, honey, I heard about what they found this morning.

I’m so sorry. She settled into a chair, clutching a tissue. That sweet little girl, she always said good morning to me when her class walked past the office. Such beautiful manners. Mrs. Fitzgerald, we were just discussing staff members who left after Lily’s disappearance, Dr. Coleman explained. Eleanor’s expression hardened slightly. The police interviewed everyone extensively back then.

They were particularly interested in Carl Brennan once that assault charge came to light. Spent hours with him. What happened with that? Norah asked. Nothing ultimately. Carl had an airtight alibi. He was at a mandated counseling session that morning as part of his probation from that old charge. Had to sign in.

was on camera at the counseling center the entire time Lily would have been walking to school. The detective said there was no way he could have been involved. Elellanar dabbed at her eyes. You know who really took it hard? Harold Walsh. That man blamed himself something terrible. He organized search parties every single weekend for months, printed thousands of flyers with his own retirement money when the official search scaled back.

I remember finding him crying by the crossing post one afternoon, saying he’d failed that little girl. Norah’s phone buzzed. Detective Martinez’s name appeared on the screen. Excuse me, I need to take this. Mrs. Whitfield, Martinez’s voice was urgent. We’ve made some progress on the rental payments. They were sent to a P.O. box at the downtown postal center. Always postal money orders purchased with cash.

Virtually untraceable, unfortunately. When did they stop? Norah asked, aware the others were politely pretending not to listen. That’s the interesting part. The payments were made quarterly, never late, until exactly one year ago. Then nothing. No forwarding address, no contact information, just stopped.

Norah’s eyes drifted back to the computer screen to the list of departures. Harold Walsh retired 13 months ago, several others around the same time. Coincidence? Surely. She was seeing patterns where none existed, her desperate mind trying to force connections. Thank you, detective. Keep me updated. She ended the call and looked at the expectant faces. They’re tracing the rental payments.

Dead end so far. Dr. Coleman leaned forward. Mrs. Whitfield, I’d be happy to reach out to some of our retired teachers if you think it would help. Sometimes people remember things years later that didn’t seem significant at the time. That’s kind of you, Nora said, suddenly exhausted.

Let me let me process everything first. This has been a lot to take in. Eleanor reached over and squeezed her hand. We’re here if you need anything. The whole school community never stopped caring about Lily. Norah thanked them and made her way back through the hallways. She paused at the memorial plaque near the entrance, a simple bronze square with Lily’s school photo and the dates that marked too short a life. Fresh flowers sat in a small vase beneath it, and someone had left a teddy bear.

Outside, the afternoon shadows stretched long across the parking lot. Eight years had scattered everyone who might have seen something that morning, dispersed them like seeds on the wind. The janitor, with his confirmed alibi, the retired teachers in their new lives, Harold Walsh, no longer at his post.

All these people who had been part of Lily’s daily world now moved on while Lily herself had been trapped in that horrible crawl space. The frustration built in her chest as she walked to her car. Every lead seemed to end in a wall, every trail grown cold with time. But something nagged at her. The timing of those rental payments stopping the cluster of retirements. Probably nothing, she told herself.

Just her desperate mind grasping at straws. The fuel gauge needle hovered just above empty as Norah drove through town, her mind still processing the horrors of the crawl space and the frustrating dead ends at the school.

She’d been running on adrenaline since Detective Martinez’s call that morning, but now exhaustion crashed over her like a wave. Her hands trembled on the steering wheel, and she knew she needed to stop before she became dangerous on the road. The Chevron station on the edge of town appeared like a familiar beacon. How many times had she pulled in here during those desperate weeks eight years ago? The owner, Dev Patel, had been one of the first to put up her missing person flyers, taping them to every pump and window.

His employees had joined search parties on their days off, walking through fields and forests in the summer heat. This place had been a refueling stop in more ways than one during those dark days. She pulled up to pump three and went through the motions of inserting her credit card, but the machine beeped angrily. “See cashier,” the screen demanded. “Of course, nothing could be simple today.

” Leaving the nozzle in her tank, she trudged toward the store entrance. The familiar bell chimed overhead as she pushed open the glass door. The same faded lenolium, the same humming refrigerator cases, the same rack of air fresheners by the register. Even the smell was unchanged.

A mixture of coffee, industrial cleaner, and gasoline fumes. Two customers stood in line ahead of her, and she mindlessly studied the candy display while waiting. The man at the counter was purchasing an odd assortment. a pint of strawberry ice cream, a small propane canister, and a pack of D batteries. His voice, when he thanked the cashier, sent a jolt of recognition through her.

That gentle cadence, the slight whistle on his s, sounds from ill-fitting dentures. Harold Walsh. He’d aged in the year since she’d last seen him. His shoulders curved inward more pronouncedly, and his thick white hair had thinned to wisps combed carefully over his scalp.

The fluorescent lights cast deep shadows under his eyes, and his crossing guard’s confident posture had given way to the cautious movements of the elderly. As he turned from the counter, receipt in hand, his pale blue eyes met hers. They widened with recognition, and his weathered face creased into that familiar sad smile that she’d seen so often during the searches.

Nora,” he said softly, shifting his purchases to one arm. “I heard about what they found this morning. I’m so, so sorry.” The genuine pain in his voice made her throat constrict. “Here was someone who’ truly cared, who’d walked miles searching for Lily, who’d wept at the memorial services.” “Harold,” she managed. “I heard you retired.

How How are you doing?” He glanced toward the parking lot where she now noticed an old Winnebago parked at the far pump. The RV had seen better days. Rust spotted its cream colored sides and duct tape patched one window. Getting by. Been doing some traveling with my niece. He paused, adjusting his grip on the ice cream. Well, adopted niece really. Her parents passed when she was young, so I took her in. Seemed the Christian thing to do.

Through the open door of the camper, Nora could see movement. A girl, maybe 14, sat at the small dinette table, visible through the side window. Long blonde hair pulled back in a ponytail around her face than Lily would have, wearing a faded blue t-shirt. The girl was focused on something, a book perhaps, absently licking an ice cream spoon.

“That’s wonderful of you,” Norah said, meaning it. After losing his wife to cancer decades ago, Harold had never remarried. She’d assumed he was alone in his retirement. Taking in a child at your age, that’s quite a commitment. “Family is family,” Harold said simply, moving toward the door.

“Norah followed, oddly comforted by this unexpected encounter with someone who’d shared her loss. “I’d love to meet her,” Norah said as they stepped into the afternoon heat. It’s nice to think of you having company after everything. She trailed off, walking alongside him toward the Winnebago. The change was instant and jarring. Harold’s shuffling gate suddenly quickened.

His shoulders went rigid, and he stepped sideways, putting himself between Nora and the camper. “She’s very shy with strangers,” he said, his previous warmth evaporating like morning dew. “We really need to get going. Long drive ahead. Oh, I didn’t mean to intrude, Norah said, taken aback by his sudden coldness. I just thought, “Sarah, get away from the door,” Harold called sharply, practically jogging the remaining distance to the RV.

The girl looked up, confused, and in that brief moment, Norah’s breath caught the freckles. Even from 20 ft away, even in the shadow of the camper, that distinctive pattern was visible. a perfect triangle of three freckles on the bridge of her nose with two smaller ones forming a line below. Not scattered randomly like most children’s freckles, but a specific constellation that Norah had kissed goodn night thousands of times.

Harold was already at the camper, yanking the door shut with a bang that made the girl jump. Through the window, Norah saw her mouth move, asking a question perhaps, before Harold’s hand pressed her away from the glass. He climbed into the driver’s seat without a backward glance, starting the engine with a roar of black exhaust. “Harold,” Norah called, but the Winnebago was already moving, pulling away from the pump with the gas hose still connected to his tank.

It popped free with a metallic clang, the safety valve shutting off the flow as the hose recoiled. Harold didn’t stop, didn’t even slow down, just accelerated onto the highway, heading north. Norah stood frozen in the parking lot, watching the Winnebago disappear around the curve. The cashier had come out, shouting about the damaged pump, but his words were just noise.

All she could see was that pattern of freckles, that unique constellation that the forensic artist had carefully replicated in every age progression photo. She was being paranoid. Eight years of false sightings had trained her to see Lily everywhere. The girl looked nothing like her daughter would. Wrong coloring, wrong build, wrong everything except except those freckles and Harold’s reaction. The gentle old crossing guard who’d organized searches who’d wept at memorials had practically fled rather than let her near that girl. His transformation from sympathetic friend to panicked stranger left her deeply

unsettled, a cold weight settling in her stomach that had nothing to do with the day’s earlier revelations. The kitchen felt too quiet as Norah stood at the stove, watching water refuse to boil. She’d pulled out a box of pasta 20 minutes ago, but her hands kept stilling, her mind drifting back to that gas station encounter.

The pot sat forgotten as she stared through the window at nothing, seeing only that brief glimpse of freckles across a teenage girl’s nose. She forced herself to move, dumping pasta into water that was barely simmering. The girl looked nothing like Lily would look now. Wrong hair, blonde where Lily’s had been, that distinctive red brown, heavier build when Lily had been slight, almost elfen, different facial structure entirely.

Thousands of girls had freckles, millions. She was doing what she’d sworn she’d stopped doing years ago, seeing her daughter in every young face. But Harold’s reaction. The pasta water boiled over, hissing against the burner. Norah yanked the pot off the heat, not even bothering to clean up the mess.

That transformation from sympathetic old friend to panicked stranger played on repeat in her mind. The way he’d practically shoved the girl back, slammed the door, fled with his gas hose still attached. That wasn’t grief making someone protective. That was fear. She abandoned the pasta entirely, and reached for her phone. “Detective Martinez,” she said when he answered. “I’m sorry to bother you again.

” “No bother, Mrs. Whitfield. What can I help you with?” She tried to keep her voice casual, reasonable. I was wondering during the original investigation, was Harold Walsh ever looked at the crossing guard. She heard typing the click of a mouse. Let me pull up the old files. Harold Walsh, age 70 at the time.

Yes, he was interviewed along with all school personnel. Clean background check, no criminal history, not even a parking ticket, 30-year reputation as a devoted school employee. Says here he was devastated by the disappearance. organized multiple search parties. More clicking. Is there a reason you’re asking about him specifically? Norah hesitated.

How could she explain a feeling? A pattern of freckles. A moment of strange behavior. I ran into him at the gas station today. He has custody of a young girl now. Adopted niece, he said. He just seemed oddly defensive when I tried to meet her. Practically ran away. Martinez’s voice carried gentle understanding. Mrs.

Whitfield, I know today has been incredibly difficult. Finding that crawl space, reliving everything. It’s natural that you’re seeing things through a different lens. Grief and trauma affect everyone differently. Many people who were involved in Lily’s case became extremely protective of children afterward. It’s a common response. You’re right, Norah said, feeling foolish. I’m sorry.

It’s been a long day. Nothing to apologize for. We’re following every lead from the rental house. If anything concrete comes up, you’ll be my first call. After hanging up, Norah found herself at her laptop typing Harold’s name into the search bar. The results were sparse. No Facebook profile, no LinkedIn, no social media presence at all. just scattered mentions in archived school newsletters.

Crossing guard Harold Walsh celebrates 25 years of service. Walsh receives community safety award. Photos showed a younger man with thick white hair and kind eyes, always surrounded by children. She nearly closed the browser when a newer result caught her eye. An article from the Pine Creek Gazette dated 13 months ago. Pine Creek RV Park celebrates 20 years.

She clicked through to find a fluff piece about the park’s anniversary featuring profiles of various residents. There, halfway down the page, was a photograph of Harold standing beside his Winnebago, the same battered vehicle she’d seen today.

Harold Walsh, our newest permanent resident, says he chose Pine Creek for its peace and quiet after retiring from his position as a school crossing guard. It’s the perfect place to enjoy my golden years with my adopted niece,” Walsh told the Gazette. The article included the park’s address, which Norah found herself copying into a notebook, her hand moving almost without conscious thought.

She climbed the stairs to Lily’s room, preserved exactly as it had been 8 years ago, down to the homework on the desk and the stuffed animals on the bed. From the closet shelf, she pulled down a banker’s box filled with photos and documents. Her hands knew exactly what they were looking for. The photo was one of her favorites. Lily at the beach the summer before she disappeared, face turned up to the camera with a gaptothed grin.

The sun highlighted every freckle in perfect detail. There they were, three freckles forming an equilateral triangle on the bridge of her nose about a centimeter apart. below that two smaller ones in a vertical line. The forensic artist had called it highly distinctive when creating the age progression images.

Norah pulled out those progression photos. Now Lily at 8, at 10, at 12, at 14. The computer generated images showed how her face might have lengthened, how her features might have matured, but always, always that freckle pattern remained constant. a constellation as unique as a fingerprint. She set the 14-year-old progression next to the beach photo.

If she imagined the hair blonde instead of Auburn added some weight to the cheeks number, she was torturing herself with impossibilities. Harold Walsh had been a fixture at that crossing for decades. He’d helped hundreds of children safely to school. He’d wept at Lily’s memorial, spent his retirement savings on search flyers. The girl was his adopted niece, just as he’d said.

The freckles were coincidence, nothing more. But as Norah closed the photo box, her eyes drifted to the notebook where she’d written the Pine Creek RV Park address. Just to put her mind at ease, she told herself, just to prove she was being paranoid. She’d drive by tomorrow, see the girl clearly in daylight, confirm she looked nothing like Lily, and put this delusion to rest.

The pasta pot still sat on the stove, contents congealed into an inedible mass. Norah dumped it in the trash and went to bed hungry, the Pine Creek address burning in her mind like a brand. Sleep had been impossible. Nora had lain in bed staring at the ceiling, seeing that constellation of freckles every time she closed her eyes.

By 4:00 in the morning, she gave up pretending and made coffee, sitting at the kitchen table with the Pine Creek RV Park address circled in her notebook. By 5:30, she was in her car, telling herself she was just going for a drive to clear her head. The RV park sat on the outskirts of town where development gave way to Pine Forest. A modest sign marked the entrance. Pine Creek RV Park.

Weekly, monthly, yearly rates available. The early morning sun cast long shadows across neat rows of recreational vehicles from massive luxury motor homes to modest travel trailers. A few early risers walked small dogs or sat under awnings with coffee cups. The office was a double wide trailer with flower boxes under the windows.

A bell chimed as Nora entered and a woman in her 50s looked up from a crossword puzzle. Her name tag read Deb manager and her face lit up at the prospect of a potential customer. Good morning. How can I help you today? I’m interested in monthly rates, Nora said, surprising herself with how easily the lie came. for a small RV. I’m going through a transition.

” “Oh, honey, aren’t we all?” Deb said warmly, pulling out a colorful brochure. “We’ve got several spots available. Let me show you around. I always say you can’t get a feel for a place without walking it.” They strolled down the main path, gravel crunching under their feet. Deb kept up a steady stream of chatter, pointing out amenities, the laundry facility, the communal fire pit, the showerhouse for folks with smaller rigs. She introduced passing residents with the ease of someone who knew everyone’s

business. That’s Robert in Space 12, retired Navy, makes the best barbecue you’ve ever tasted. The Hendersons in Space 20 just had their first grandchild. They’re over the moon. And way down at the end there, space 38. That’s Harold Walsh. Keeps to himself mostly. Norah’s pulse quickened. Seems like a nice mix of people.

Oh, it is. Harold’s a quiet one, though. Keeps odd hours, often gone during the day. Sweet girl he’s got with him. They’ve been here about a year now. Deb lowered her voice conspiratorally. He homeschools her. Says the regular schools don’t challenge her enough. Must be true. I’ve seen her reading college level textbooks.

That’s dedicated. Homeschooling at his age, Norah observed. Family is everything, Deb said, echoing Harold’s own words from yesterday. Well, I’ll let you wander around, get a feel for the place. Just stop back at the office before you go, and we can talk specifics about rates and availability. Norah thanked her and continued down the path, pretending to evaluate the facilities.

She paused at the communal area, studied the bulletin board covered in community announcements, all while gradually making her way toward the far end of the park. Space 38 was indeed private, backed against a thick stand of pines.

Harold had enhanced that privacy with a makeshift fence of lattice panels and blue tarps strung between posts. It created an enclosed area around the Winnebago’s entrance, shielding it from casual view. A small awning extended from one side with two folding chairs and a camp table beneath it. Norah approached slowly, ears straining for any sound. Then she heard it, a young girl’s voice humming tunelessly from inside the RV.

The melody was unfamiliar, meandering, the kind of song someone makes up as they go along. The windows all had heavy curtains drawn, but one had a gap where the fabric didn’t quite meet. Heart pounding, Nora moved closer, positioning herself where she could see through that small opening. The girl sat at the dinette table, bent over what looked like a sketchbook, colored pencils scattered around her.

Her blonde hair was loose today, falling forward to curtain her face as she drew. On the table beside her sat an open container of ice cream, Strawberry, the same brand Harold had purchased at the gas station. The girl absently took a spoonful. Her attention focused on her drawing. As she did, a bit of melted ice cream dripped onto her left arm. Without looking, she scratched at the spot with her other hand.

Norah’s breath caught. Even from 10 ft away, she could see the angry red welt rising on the girl’s skin near her elbow. The reaction was immediate and localized. A raised inflamed patch about 2 in across. The skin swelling and reening as Norah watched. The memory crashed over her like a physical blow.

Lily at 4 crying in the kitchen, her arm covered in that same angry rash. The rushed trip to urgent care. The allergist’s explanation. It’s unusual. Most strawberry allergies present as systemic reactions, hives all over, respiratory issues. But Lily has what we call localized contact dermatitis. Her skin cells in that specific area have an extreme sensitivity to strawberry proteins. It’s quite rare.

They’d had to be so careful after that. No strawberry anything in the house. Always checking labels, warning every babysitter, every teacher, and that specific spot. Always the left arm near the elbow where her skin was most reactive. The allergist had said it was like a fingerprint, that unique presentation in that exact location.

The girl in the RV scratched again at the spreading rash, finally looking down with annoyance. She grabbed a paper towel and wiped the ice cream away, but the damage was done. The rash would last hours now, Norah knew, just like it always had with Lily. She backed away from the window, her legs barely supporting her. In her car, she fumbled for her phone.

Detective Martinez’s number blurring through tears. She didn’t remember starting to cry. The strawberry allergy. She gasped when he answered. Left arm near the elbow. Localized contact dermatitis. It’s in her medical records. Dr. Patel at Children’s Hospital documented it extensively. No one else would have that exact reaction in that exact spot.

The odds are impossible. Martinez’s professional calm cracked. You’re certain. You saw this reaction? I watched it happen. She’s eating strawberry ice cream right now. The rash is spreading exactly like it did with Lily. Same location, same pattern, same everything. Where are you exactly? Pine Creek RV Park near space 38. But I can move.

Return to the main office area immediately. Park where you can see the entrance but not the specific space. Units are already rolling. This is substantial enough for intervention. Mrs. Whitfield, we’re coming now. Norah forced herself to drive slowly back to the front of the park, each yard feeling like a mile.

She parked near the office where Deb waved cheerfully through the window, oblivious to the police units racing toward them. From here, she couldn’t see Space 38. Couldn’t see if Harold was home. couldn’t see anything but the main entrance where Martinez’s units would arrive.

She gripped the steering wheel until her knuckles went white, checking the rearview mirror every few seconds, praying Harold wouldn’t choose this moment to leave. Praying the girl, Lily, it had to be Lily, would still be there when help arrived. Three police units rolled into the park without sirens, their quiet arrival more ominous than any wailing alerts.

Detective Martinez’s unmarked sedan led the convoy. He parked beside her and approached her window, his expression professionally neutral, but his eyes sharp with urgency. Mrs. Whitfield, I need you to stay here. We’re going to check space 38. If this is your daughter, we need to handle it carefully. I understand, she said, though every fiber of her being wanted to run toward that distant RV space.

She watched the officers move down the main path, their movements coordinated and purposeful. Other residents emerged from their RVs, curious about the police presence. Deb hurried out of the office, her crossword puzzle forgotten, mouth open in confusion. The weight was excruciating. Nora could see the officers disappear around the bend toward the back of the park.

Could imagine them approaching space 38 surrounding the Winnebago. Any moment now, they’d have answers. Any moment now, 8 years of agony might end. Martinez’s radio crackled. Even from inside her car, she could hear the tension in the officer’s voice. Unit one. The space is empty. RV’s gone. Fresh tire tracks. Looks like a hasty departure. Norah’s heart plummeted.

She was out of her car before she realized she’d moved, rushing toward Martinez as he jogged back from the rear of the park. Deb intercepted them both, her face flushed with anxiety. What’s happening? Why are police here? Is everyone okay? Martinez pulled out his phone, showing her a photo of Harold. This man, Harold Walsh in Space 38.

When did you last see him? Harold? He He paid his monthly fee yesterday, but I saw his rig pull out maybe 20 minutes ago. 25. He used the back service exit. She pointed toward the rear of the park. It connects to the old logging road. Folks use it sometimes to avoid traffic on the main highway. Did something happen? Where would he go? Martinez pressed. Does he have a favorite camping spot? Somewhere isolated.

Deb’s hands fluttered nervously. He mentioned yesterday when he paid, he said something about his favorite spot near Cedar Creek. said he was thinking of taking his niece camping for her birthday. “It’s an old Forest Service clearing,” he said. No one ever bothers him there. “Where exactly?” Forest Service Road 47 about 12 mi up the mountain, past the old fire tower.

It’s pretty remote. No cell service, nothing up there but trees in the creek. Her voice rose with worry. “Is the girl okay? Is Sarah okay?” Martinez was already moving, barking orders into his radio. Roadblocks on the highways, units to Forest Service Road 47. All available backup to converge on the mountain.

He turned to Norah, his expression stern. You need to stay here. This could be dangerous. But Norah was already backing toward her car. That’s my daughter up there, Mrs. Whitfield. She was in her car and following the convoy before he could finish his protest. If Martinez radioed for someone to stop her, she didn’t know.

All she knew was that Lily was 12 mi up a mountain with a man who’d stolen 8 years of their lives. The police units ahead maintained steady speed on the winding mountain road. Dense pine forests pressed in on both sides, the morning sun barely penetrating the canopy. The road switched back and forth, gaining elevation with each turn.

Norah’s car strained on the steeper sections, but she kept pace, her hands steady on the wheel despite the trembling in her chest. 10 m 11. The abandoned fire tower appeared through the trees, its skeletal frame rusty with age. 12 m. The lead unit’s brake lights flared and Martinez’s voice crackled over someone’s radio loud enough for her to hear.

Winnebago spotted. Clearing ahead. All units prepare for approach. The clearing opened up like a wound in the forest, a flat area maybe 50 yards across, surrounded by towering evergreens. Cedar Creek gurgled along the far edge, its water dark with tannins. And there, parked half-hazardly near the treeine, sat Herald’s battered Winnebago.

Police units fanned out in practiced formation, blocking any escape route. Officers exited their vehicles, using them as shields, weapons drawn, but held low. Norah pulled in behind the last unit and was immediately approached by an officer who tried to direct her back, but Martinez waved him off.

“Let her stay, but keep her behind the line,” he ordered, then raised a bullhorn. Harold Walsh, this is Detective Martinez with the County Sheriff’s Department. We need you to exit the vehicle with your hands visible. Silence. Even the forest seemed to hold its breath. No birds sang. The creek’s babble sounded too loud in the stillness. Harold, we know you have the girl. We know it’s Lily Whitfield.

Let’s resolve this peacefully. Come out and talk to us. More silence, then muffled from inside the RV, a girl’s voice, scared, confused. Norah’s knees nearly buckled at the sound. After 8 years, her daughter’s voice changed by time, but still holding that particular timber she’d know anywhere. The Winnebago’s door opened slowly.

Harold appeared first, and Norah gasped at the transformation. Gone was the gentle crossing guard. His face was haggarded, eyes wild, and in his right hand he clutched a hunting rifle. His left arm was wrapped tightly around the girl, pulling her against him as a shield. The girl was sobbing, mascara streaming down her cheeks.

When had Lily started wearing makeup, she looked exactly as Norah had imagined, and nothing like she’d expected. The blonde hair threw her, as did the fuller figure, but those freckles were unmistakable, even from across the clearing. Grandpa, what’s happening? The girl cried. Why are there police? What did we do? Shh, Sarah. It’s okay, Harold said, his voice cracking. Then louder to the officers. You don’t understand. I saved her.

Her parents, they didn’t deserve her. Letting a six-year-old walk to school alone in this world. I gave her everything. I taught her everything. She’s my daughter now. Harold. Martinez’s voice through the bullhorn was steady, calm. No one wants anyone to get hurt. Put the weapon down and let’s talk. There’s nothing to talk about.

Harold’s voice rose to nearly a scream. 8 years. 8 years I’ve been her family. I’m all she knows. You can’t just take her away. Somewhere to Norah’s left, an officer’s radio crackled with static. The sharp sound made Harold jerk toward it, the rifle barrel swinging momentarily away from the girl’s temple. In that split second of distraction, the girl must have felt his grip loosen.

With the instinct of a trapped animal, she wrenched free and ran. Her blonde ponytail streamed behind her as she sprinted toward the police line, toward safety, toward a mother she didn’t remember. For one hearttoppping moment, Harold swung the rifle toward her retreating form. Norah screamed, the sound ripping from her throat.

Officers shouted commands. The girl kept running, stumbling on the uneven ground, but not stopping. Then Harold’s face crumpled. As officers moved in from their positions, he turned the rifle toward himself, placing the barrel under his chin.

Two officers, who had positioned themselves closest, Norah hadn’t even noticed them creeping forward, rushed him with tasers. The electrical charge hit him before his finger found the trigger. Harold convulsed and collapsed, the rifle falling harmlessly to the pine needle-covered ground. The officers were on him in seconds, kicking the weapon away, securing his hands behind his back while he sobbed incoherently into the earth.

The girl had reached the police line, but stood frozen, watching the takedown with horror. When Norah broke past the officers, calling, “Lily, Lily!” The girl shrank back, her tear streaked face full of confusion and fear. “My name is Sarah,” she said, her voice small and broken. “My parents are dead.

Who are you? Why is everyone lying?” She wrapped her arms around herself, backing away from this stranger who claimed to be her dead mother, looking desperately for the only parent she remembered. The old man, now face down in handcuffs, still sobbing about saving her, about giving her a better life. An officer gently stepped between them, speaking softly to the girl. You’re safe now. No one’s going to hurt you.

We’re going to take you to the hospital to make sure you’re okay. I don’t need a hospital. The girl’s voice rose with panic. I need my grandpa. He’s sick. He has diabetes. He needs his medication. She tried to push past the officer toward Harold. Grandpa, tell them. Tell them about the accident. Another officer had approached Nora, placing a gentle hand on her shoulder.

Ma’am, we need to let the paramedics check her out. You can follow us to the hospital. Norah nodded numbly, watching as EMTs approached the terrified girl with careful, practiced movements. They spoke to her softly, calling her Sarah, not challenging her reality yet. One of them, a woman with kind eyes, managed to coax her toward the ambulance with promises that they were just making sure she wasn’t hurt, that someone would explain everything soon.

As they guided her past where Harold lay on the ground, the girl broke free for a moment, dropping to her knees beside him. I’ll find a lawyer, Grandpa, like you taught me. I know my rights. I won’t let them take me away. Her young voice was fierce with determination, even as tears rolled down her cheeks. You’re all I have. You’re all I’ve ever had.

The EMTs gently pulled her away, and this time she didn’t resist, stumbling toward the ambulance like a sleepwalker. At the doors, she turned back one more time, her eyes scanning the clearing until they found Nora. For just a moment, something flickered in her expression. Not recognition exactly, but a shadow of confusion, as if some deep part of her mind was trying to reconcile what she saw with what she’d been told.

Then the moment passed, and her face hardened again. “My mother is dead,” she stated flatly, climbing into the ambulance. “Whoever you are, my mother is dead.” The doors closed and Norah stood in the mountain clearing, surrounded by police and chaos, watching the ambulance carry her living daughter away.

A stranger wearing Lily’s freckles, carrying 8 years of someone else’s lies. The hospital’s pediatric ward smelled of disinfectant and floor wax, institutional scents that brought back memories of Lily’s birth 14 years ago. But the girl in the examination room bore little resemblance to the child Norah remembered. She sat rigid on the hospital bed, arms crossed defensively, her blonde hair tangled and her face set in stubborn denial.

I want to see my grandpa, Lily said for the 10th time, her voice rising. “You can’t keep me here. I know my rights. He taught me about false imprisonment.” The nurse adjusting her IV looked helplessly at Nora, who stood frozen by the door, afraid to move closer and trigger another outburst. The first time she’d approached, Lily had screamed and thrown a water pitcher. “Sweetheart,” the nurse tried again. “You’re safe here. We just need to My name is Sarah.

” Lily’s eyes flashed with anger. Sarah Walsh. My parents died in a car accident when I was six. June 15th, interstate pileup, three cars, instant. She recited the words like a mantra, her fingers twisting the hospital blanket. Grandpa showed me the newspaper articles. He kept them in a folder so I wouldn’t forget them.

Norah’s heart shattered with each word. The fabrication was so detailed, so thoroughly constructed. Lily, please stop calling me that. The girl’s voice cracked. My mom is dead. Dead? Why is this woman lying? Why won’t anyone tell me the truth? She turned, pleading eyes to the nurse. Please, I need my grandpa. He’s all I have.

He’s probably so worried. When Norah stepped forward instinctively. Lily became hysterical. She ripped the IV from her arm, blood spotting the white sheets, and lunged for the door. It took two orderlys to gently restrain her while the doctor administered a mild seditive. “I want to go home,” Lily sobbed as the medication took effect.

“Please, I want my grandpa. We were going camping for my birthday.” He promised. 20 m away, in a gray interrogation room at the county police station, Harold Walsh sat across from Detective Martinez. The old man looked smaller without his crossing guard authority. His shoulders curved inward, handscuffed to the table. His confession came in fits and starts punctuated by justifications and tears.

My wife died 30 years ago, he began, his voice barely above a whisper. She was pregnant. I lost them both to cancer. The loneliness. You can’t understand what 30 years of it does to a person. Martinez remained silent, letting him talk. I watched those children every morning for decades. Watched parents who didn’t appreciate what they had.

That morning, seeing little Lily walking alone again, his face contorted. Something just snapped. I’d already called in sick. I’d been thinking about it for weeks, how unsafe it was. A six-year-old walking alone. So, you took her? I saved her, Harold insisted. I told her there was an emergency at home that her mother asked me to pick her up. She trusted me. I’d been helping her across the street for months.

I love her. I took care of her. She loves me, too. Please don’t take her away from me. The newspaper clippings about the accident. Harold’s eyes darted away. I made those. Had an old desktop publishing program. Spent weeks getting the details right. Whenever she’d question things, remember things, I’d show them to her. Tell her the trauma was making her confused.

Tell me about the house on Willow Creek Road. The old man’s face crumpled. 7 years we lived there. I homeschooled her, kept her safe. When she’d fight me about her memories, when she’d insist her parents were alive. He paused, swallowing hard. The crawl space was time out, never more than a few days.

I tried to make it comfortable. Brought her poster, her favorite foods. You chained her in a crawl space. Only when she was being difficult, when she wouldn’t accept reality. Harold’s voice rose defensively. I gave her everything. Education, love, safety. The hair dye was to help her start fresh. I told her it was medicine, vitamins to keep her healthy. She believed me.

She learned to trust me. Why leave the evidence behind? Harold’s shoulders sagged. The district mandated retirement age. I couldn’t be the crossing guard anymore. Had to leave quickly, find somewhere new. I thought the house would be demolished. Never imagined. Martinez leaned forward.

When did she stop fighting you? Two years in, Harold whispered. She stopped asking about her parents, started calling me grandpa. She was happy. We were happy. I gave her a better life than parents who’d let her walk alone. Back at the hospital, Dr. Patricia Moreno sat with Nora in a quiet consultation room.

The child psychologist’s expression was kind but serious, her words carefully chosen. Lily has experienced severe psychological manipulation and trauma bonding, she explained. The false memories Harold created are deeply embedded. Her real memories aren’t gone, but they’re buried under 8 years of consistent false narrative.

Will she remember me? Norah’s voice was barely audible. The memories of her early life exist. The brain doesn’t simply delete experiences, but accessing them through the layers of manipulation will take time, extensive therapy, years, possibly. And I need to be honest. There’s no guarantee she’ll fully recover those early memories. But she’s alive, Norah whispered. She’s alive. Dr. Moreno squeezed her hand.

She’s alive and she’s safe. Everything else we take one day at a time. Through the observation window, Nora watched her daughter sleep. The sedative had smoothed the angry lines from her face, and in rest, she could see traces of the six-year-old who’d walked to school that morning 8 years ago. The freckles were unchanged, that distinctive constellation that had led her home.

But everything else, the blonde hair, the suspicious eyes, the defensive posture even in sleep, belonged to a stranger named Sarah Walsh. In her hands, Norah held Lily’s medical file. The blood work confirmed what she already knew. Severe strawberry allergy, localized reaction typical at the left anterior elbow. Such a small thing, a quirk of skin cells and histamines.

Yet, it had broken through 8 years of lies, revealed a truth Harold had tried to bury. She pressed her palm against the window, watching her daughter breathe, and made a silent vow. However long it took, however many therapy sessions, however many rejections and setbacks, she would help Lily remember. Or if the memories stayed buried, they would build new ones.

The six-year-old was gone, but the 14-year-old was here, alive, found. The medical files pages rustled in her trembling hands that confirmation of the strawberry allergy a bitter irony that something so small, so specific to her daughter’s body had revealed eight years of captivity when everything else had failed.