On December 14th, 1950, 31 miners descended into the Bracken Ridge coal mine in Hazelton, Pennsylvania for the night shift. None of them ever came back up. The official report stated that a catastrophic cave-in at 11:47 p.m. killed all men instantly. The company paid generous settlements to the families, double the standard rate, with one condition.

Never speak publicly about that night. The mine was sealed with industrial concrete and Hazelton moved on from its tragedy. But 55 years later, when a demolition crew broke through a sealed basement while clearing the old Bracken Ridge mining offices, they found something that shouldn’t exist. Wire spool recordings from the mine’s emergency radio system preserved in an engineer’s lockbox.

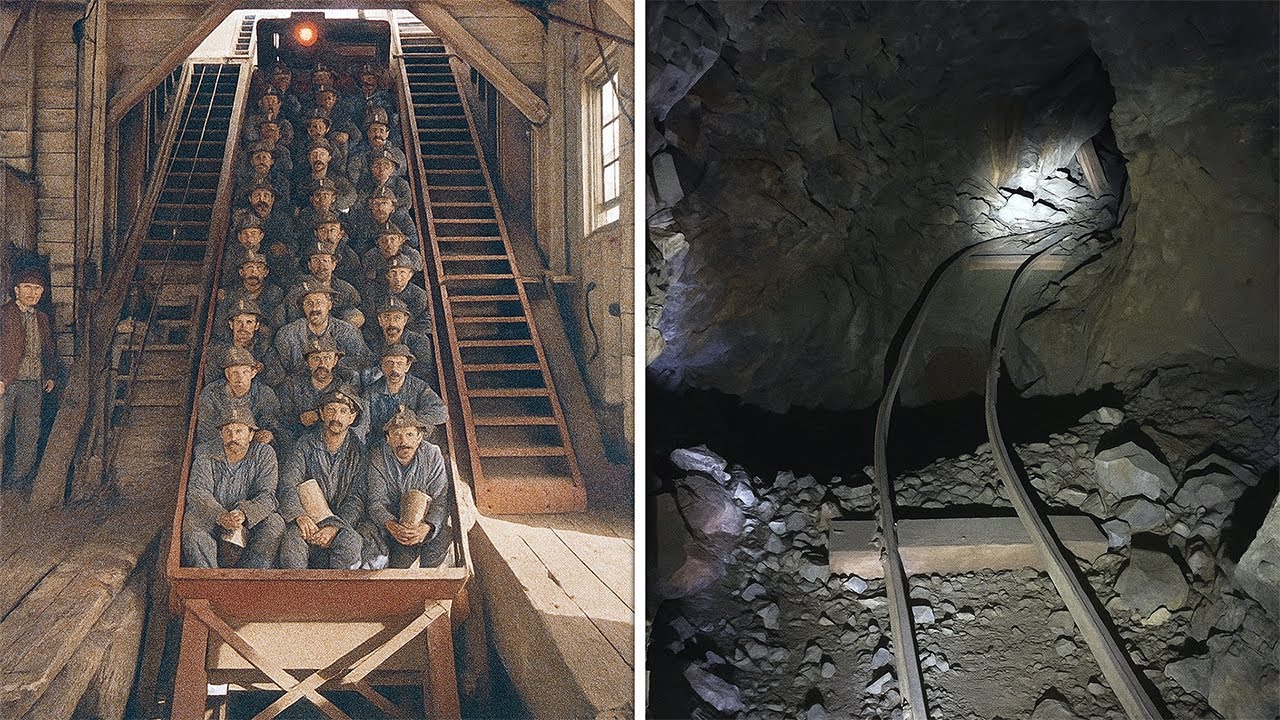

The recordings captured 47 hours of desperate transmissions from the trapped miners. 47 hours after they were declared dead while rescue equipment drilled in the wrong direction and concrete trucks arrived to seal them in forever. What investigators heard on those recordings would reveal that 31 men didn’t die in an accident.

They were murdered by the men who listened to their pleas for help and chose to bury them alive. The sledgehammer connected with the wall and Jake Mitchell felt the floor shutter wrong. Not the solid thought of impact against good foundation, but that hollow drumlike vibration that meant empty space where there shouldn’t be any.

He’d been on enough demolition crews to know the difference. “Hold up,” he called to Tommy Garner, who was winding up for another swing at the loadbearing beam. “Something’s off.” They were 3 days into tearing down the old Bracken Ridge Mining Company headquarters in Hazelton, Pennsylvania. The building had been empty since 1987.

Windows boarded, copper pipes long since stripped by scavengers, but the bones of the place were solid. That old-fashioned construction with beams thick as tree trunks and foundations that went down deep. Tommy lowered his hammer. What is it? Jake knelt, pressing his palm flat against the floorboards.

The wood was warped with age, that particular ripple that comes from decades of humidity with no climate control. But underneath, where the subfloor should have been solid on concrete, he felt it again. That wrongness. Get me the pry bar. The first board came up easy. Too easy. The nails were rusted through, barely holding. Underneath, instead of the expected subflooring, there was a gap.

Jake aimed his flashlight down through the hole. Jesus Christ. What? Tommy crowded in beside him. There’s another room down there. Not just a crawl space or a utility gap. Jake could see furniture edges in the darkness, a desk, what looked like filing cabinets, a hidden basement level that didn’t appear on any of the building schematics they’d been given. It took them 40 minutes to pull up enough flooring to make an entry point.

Jake went down first, the wooden ladder they’d improvised creaking under his weight. The smell hit him immediately, not mold or rot like you’d expect, but something else. Paper, old paper and leather, and that particular staleness of air that hasn’t moved in decades. His flashlight swept across the space.

It was an office, frozen in time. The desk was metal, military surplus style, covered in a thick layer of dust. Filing cabinets lined one wall. But what made Jake’s throat close up was the wall behind the desk, covered in maps. Mining maps with sections marked in red ink, dates written in careful handwriting. December 1950.

Jake, you okay down there? He didn’t answer. Couldn’t because he just seen the name plate on the desk, barely visible under the dust. Robert Sterling, chief engineer. His grandfather had died in the Bracken Ridge mine in December 1950. Jake’s hands were shaking as he opened the first desk drawer. Empty.

Second drawer, same, but the third was locked. He grabbed the pry bar, not caring about preservation. The lock snapped with a sound like a gunshot in the closed space. Inside was a metal lock box, heavy enough that he needed both hands to lift it. No lock on this one, just a simple latch that opened with a soft click. The contents made no sense at first.

several round metal canisters, the kind that looked like film reels, but different, heavier. There was a folded paper on top, brittle with age. Jake opened it carefully. It was a shift log. December 14th, 1950. Night shift. 31 names listed in neat columns. Third name down, Carl Mitchell. Foreman, Jake’s grandfather. His chest went tight.

that familiar ache that came whenever he encountered some unexpected reminder of the grandfather he’d never met. But this was different. This was hidden, deliberately concealed. Why would the chief engineer hide a routine shift log in a secret office? Tommy’s voice drifted down. Jake, we need to get down here now.

Tommy descended, followed by their supervisor, Bill Hutchkins, who took one look at the space and pulled out his cell phone. We need to stop work. This is This could be historical. But Jake wasn’t listening. He’d found more papers under the metal canisters, receipts, delivery orders, all dated December 15th to 16th, 1950. The day after the mine collapse that killed his grandfather, 47 tons of industrial-grade concrete rushed delivery. His stomach dropped through the floor.

“Why would they need concrete?” he said, not really asking anyone. The mine collapsed. You don’t pour concrete on a collapse. Bill was examining the maps on the wall now using his own flashlight. Jake, you need to see this. The map showed the Bracken Ridge Mine layout in detail. Tunnels spreading like veins beneath the town. But there were two versions layered on top of each other.

The official layout in black ink and another version in red showing additional tunnels. tunnels that went where they shouldn’t go, under the Suscuana River. “That’s illegal,” Bill said quietly. “Mining under a river without federal permits. That’s a federal crime,” Jake finished. He turned back to the desk, pulling out everything now.

“More receipts, equipment rentals, and then at the very bottom, a leatherbound journal. Robert Sterling’s personal notes.” Jake opened it to December 1950. The handwriting was cramped, desperate. December 14th, 11:47 p.m. Water breach in section 7. Men trapped but alive. Bracken Ridge ordering seal. This is mu

rder. December 15th, 200 a.m. They’re still transmitting. Can hear them on the emergency frequency. 31 voices. Bracken Ridge won’t let rescue crews through. December 15th, 8:00 a.m. Concrete trucks arriving. God forgive us. Jake’s hands were shaking so bad he nearly dropped the journal. Tommy was reading over his shoulder. Holy They were alive. There was more. So much more. But Jake’s eyes locked on one line.

December 16th, 400 p.m. Carl Mitchell still organizing the men. His transmissions are clear. He knows we can hear him. He knows we’re not coming. Jake set the journal down carefully, his vision going blurry. 31 men, including his grandfather, trapped underground, alive, calling for help, while the company poured concrete to seal them in. “We need to call the police,” Bill said.

“But Jake had found something else in the lockbox. A photograph, black and white, creased, but clear. The entrance to the Bracken Ridge mine, not collapsed, not damaged, being filled with concrete while men in suits watched the date stamp in the corner. December 15th, 1950, 9:47 a.m. 10 hours after the supposed cave-in, while 31 men were still alive underground, Jake lifted one of the metal canisters.

It was heavier than expected, and there was something printed on the side in fading letters. Wire recording. Emergency mine frequency. December 14 to 17, 1950. His grandfather’s voice might be on these recordings. his last words, his calls for help that were deliberately ignored. “Don’t touch anything else,” Bill said, but his voice sounded far away. “This is a crime scene.” Crime scene. 55 years old, but yes, this was evidence of murder.

31 counts of murder covered up with concrete and cash settlements and decades of silence. Jake stood there in Robert Sterling’s hidden office, surrounded by evidence of the worst betrayal imaginable. His grandfather hadn’t died in a mining accident.

He’d been murdered by men who heard his cries for help and chose to bury him alive rather than face federal charges for illegal mining. The metal canisters sat there holding voices from the dead. Voices that had been silenced for 55 years. But not anymore. Call the police, Jake said, his voice steady now despite the rage building in his chest. and tell them to bring whoever handles cold cases because 31 men were murdered in 1950 and I’ve got the proof right here.

He picked up the photograph again. Those men in suits watching the concrete pour. One of them would be William Brackenidge, the mine owner. Standing there in his expensive coat, checking his pocket watch while 31 men called for help on the emergency radio frequency just hundreds of feet below.

Jake wondered if they could hear the hammering from underground, the desperate pounding of men who knew they were being sealed in. Or maybe they were too deep. Maybe all Brackenidge heard was the rumble of concrete trucks and the clink of coffee cups as they watched a mass grave being poured.

The rage was cold now, crystallized into something harder. These recordings would change everything. The town’s history. The families who’d been paid for their silence. the Brackenidge dynasty that still owned half the county. 55 years of lies were about to end. Jake Mitchell sat in Vernon Holt’s cluttered repair shop, watching the old man’s hands shake as he threaded the wire recording onto the playback machine.

Three days had passed since the discovery in Sterling’s hidden office. Three days of police tape and evidence teams and questions Jake couldn’t answer, but they’d released the recordings to him. copies, they said after confirming he was Carl Mitchell’s grandson. “Haven’t seen one of these in 30 years,” Vern muttered, adjusting the playback head with a jeweler’s precision.

His workshop smelled of solder and old electronics, shelves stacked with radios and televisions from every decade since the 1940s. Wire recordings were already obsolete by 1950, but mines used them because they were durable, could survive conditions that would destroy tape. Jake’s father, Dennis, sat in the corner, arms crossed, jaw tight. He hadn’t wanted to come.

Nothing good will come of this, he’d said. But he was here now, watching Vern work with the kind of attention that suggested he was fighting not to leave. Your dad know we’re doing this? Dennis asked. Dad, you are my dad. I mean, Bill Holt, Vern’s father. Does he know? Vern’s hand stilled for a moment. My father’s been dead 12 years.

But yeah, he would have wanted to know. He glanced back at Dennis. His dad died down there, too. Roy Henderson. The machine was ready. Vern had explained it would take time. The wire was fragile. Could snap if played too fast. They’d have to go careful, patient. Jake wanted to tear through all of it. Hear everything immediately.

But Vern set the speed low, gentle. Here we go, Burn said and hit play. Static first, then crackling, then emergency frequency check. This is Bracken Ridge Mine section 7. Foreman Carl Mitchell reporting. We have 31 men accounted for. Water breach in the main tunnel, but we’ve reached high ground. Requesting immediate assistance.

Jake’s throat closed. His grandfather’s voice. calm, professional, alive, not panicked, not desperate, just doing his job, making his report, expecting rescue. Time is approximately midnight, December 14th. We’re in the auxiliary chamber above section 7. Air is good. We have water and lunch pales, approximately 2 gall total. Battery power on the emergency transmitter is strong.

Please confirm receipt of this transmission. Silence. Then Carl’s voice again, still steady. Bracken Ridge control, this is Mitchell in section 7. 31 souls requesting assistance. We can hear water moving below us, but our position is secure. Please respond. Dennis made a sound low in his throat. His hands were white knuckled on his knees, more ecstatic.

Then another voice, younger, frightened. Why aren’t they answering, Carl? They’re probably organizing the rescue. Save the battery, boys. 10 minutes every hour. That’s all we broadcast. Vern fast forwarded carefully. The wire sang as it spooled through. He stopped at another marker. Hour four.

Carl’s voice slightly less steady now. This is Mitchell. Section 7. 31 men awaiting rescue. We can hear drilling. Repeat. We can hear drilling, but it sounds like it’s moving away from us. Please confirm you have our position. We are in section 7, auxiliary chamber, above the water line. Jake heard it then in the background. Faint but definite.

The sound of drilling equipment, but Carl was right. It sounded distant, getting more distant. They’re drilling the wrong way, Jake said. Vern nodded grimly. Keep listening. Hour eight. Mitchell section 7. The drilling has stopped. Please advise on rescue status. We’ve distributed the water.

Eddie Coleman has a broken shoulder from the initial collapse, but he’s stable. The men are in good spirits, but we need to know you’re coming. Please respond. Please. That last please. The first crack in Carl Mitchell’s professional composure. Dennis stood abruptly. I can’t sit down, Jake said, surprised by the hardness in his own voice. You need to hear this.

Hour 12. The recording continued. Different voice now, also professional, but with an undertone of worry. This is Roy Henderson taking over transmission duties. Foreman Mitchell is conserving his strength. We can hear new equipment above us. Heavy machinery. Sounds like trucks. Multiple trucks. Please advise on rescue timeline. The men want to know if you’ve notified our families. Vern’s face had gone pale.

That was his father’s voice. Roy Henderson, dead at 32, leaving behind a pregnant wife and three kids. Hour 16, Roy continued. We’re now hearing what sounds like concrete mixers. That can’t be right. Please confirm the sounds we’re hearing are rescue equipment. The men are getting concerned.

Jake felt his stomach turned to ice. 16 hours after the collapse, and the concrete trucks were already there. Carl’s voice returned, exhausted now. Hour 20. This is Mitchell. We need confirmation that you’re attempting rescue. The water’s rising slower than expected, but it is rising. We’ve moved to the highest point. I’m going to read the names of all men present for the record. He began reading.

31 names each said clearly, carefully. Jake heard his grandfather give weight to every single name, making sure they’d be remembered. Roy Henderson, Dale Watson, Jimmy Sullivan, Frank Morrison, Eddie Coleman, Tom Garrett, on and on. All present, all alive, waiting for rescue. Static, then barely audible, someone in the background.

They’re not coming, are they? They’re coming, Carl said, but not into the transmitter. To his men. They have to be coming. Vern stopped the playback. His hands were shaking worse. Now there’s more. Hours and hours more. But I need to tell you something first. He looked at Dennis, my mother, Royy’s wife. She swore she heard his voice on the radio.

December 15th, middle of the day. She had my father’s emergency frequency radio in the kitchen. Always did when he was on shift. She said she heard him calling. Dennis’s face was gray. My mother said the same thing. said she heard Carl on the radio calling for help. The company told her it was impossible.

That grief was making her imagine things. “They were transmitting on the emergency frequency,” Jake said slowly. “Any radio tuned to that frequency would pick it up.” “Unless someone was jamming it,” Burn said. “He pulled out a box of papers. I’ve been researching since you called.

” December 15th, 1950, the FCC received complaints about radio interference across northeastern Pennsylvania. Powerful jamming on the emergency mine frequency. The investigation was dropped after Bracken Ridge Mining made a donation to the FCC commissioner’s re-election campaign. Jake wanted to punch something to tear the whole shop apart.

They jammed the signals. The families might have heard fragments, pieces that got through, but not enough. Not enough to prove their men were alive while the concrete was being poured. Play more, he said. Hour 24. Carl’s voice now. We know you can hear us. The drilling earlier, it was in section three. We’re in section 7. You’re going the wrong way. Please.

Section 7. Write it down. Tell the rescue crews. Section seven. A different voice angry. They know where we are. They have to know. Why are they? Stay calm. Carl, firm despite exhaustion. Panic is the enemy. We stay calm. We stay alive. Hour 30. Roy Henderson again. The concrete sound is getting louder.

We don’t understand what’s happening up there. If you’re sealing secondary tunnels to prevent further flooding, please be advised we are above the water line. Repeat. We are above the waterline. We have time. You have time to reach us. Then, terrible in its clarity, a younger voice. Oh, God. Oh, God. They’re sealing us in. They’re sealing the mine. That’s not possible, Carl Sharp. The company wouldn’t.

Then what’s the concrete for, Carl? What’s the concrete for? Vern stopped the playback. The shop was silent except for the hum of old electronics. There’s 17 more hours, Burn said quietly. 17 more hours of them slowly realizing what was happening, organizing the remaining water, sharing the last of their carbide for light.

Carl keeps them together, keeps broadcasting even after they all know. Dennis was crying silently, tears running down weathered cheeks. Jake stood, pacing, hands clenched. We need to get these to the police, to the FBI, to someone. There’s more you need to hear first, Burn said. He forwarded to near the end. Hour 45. Carl’s voice, barely a whisper now, but still clear.

If someone finds these recordings, know that we didn’t die in the collapse. 31 men survived. We called for help for 2 days. They heard us. I know they heard us because we could hear them working above us, sealing us in. William Brackenidge, if you’re listening to this, you murdered us.

You murdered 31 men to hide your illegal mining operation. Our blood is on your hands. A pause, then stronger. To our families, we love you. We talked about you constantly. Every memory, every story. You kept us human down here in the dark. We’re scratching our names into the walls so you’ll know we didn’t just disappear. We existed. We fought. We tried. Tell our children we were brave.

Tell them we The recording cut to static. Battery died, Vern said unnecessarily. The shop was tomb silent. Dennis stood abruptly and walked out, the bell above the door chiming inongruously cheerful. Jake started to follow, but Vern caught his arm. There’s something else. My father, before he died, he told me something.

Said there was a man who came to the house in 1951 late at night, gave my mother an envelope full of cash and said it was from concerned citizens who wanted to help. But the man said if she ever talked about hearing Royy’s voice on the radio, the money would stop and other things might happen. Threats. My mother took the money. Five kids to feed, no husband.

She took it and never spoke about the radio transmissions again except to my father years later and he told me. Vern looked at the wire recorder. They all knew Jake. The whole town knew something was wrong, but Bracken Ridge Money kept everyone quiet. Jake picked up the container with the remaining wire spools. Not anymore. These recordings are going public tonight. Bracken Ridge’s grandson is a state senator now.

They still own half the county. I don’t care if they own the whole state. 31 men called for help while they were being buried alive. Everyone’s going to hear their voices. He walked toward the door, then stopped. Make copies first. Multiple copies. Hide them in different places. Vern nodded. What are you going to do? Jake thought of his grandfather’s voice, calm and professional, even while being murdered, keeping his men together, maintaining dignity in the face of unthinkable betrayal.

I’m going to finish what he started. I’m going to make sure everyone knows their names. The wire recordings spread through Hazelton like wildfire. Jake had uploaded them to the internet at 3:00 a.m. And by noon, Carl Mitchell’s calm voice, counting off 31 Living Men, was playing on every news station in Pennsylvania. But Jake wasn’t watching the news.

He was back in Vern’s shop, listening to hour after hour of recordings they hadn’t played yet. Hour 18. Roy Henderson’s voice crackled through the old speaker. The men want their families to know specifics. I’m going to let them talk. A younger voice, maybe 20. Ma, it’s Tommy. Tommy Garrett. I’m okay. We’re all okay. Tell Susan I love her. Tell her we were going to have that June wedding after all.

When I get out, I mean when they get us out. Another voice, older, grally. This is Frank Morrison. Helen, I left the mortgage payment in the coffee tin above the stove. Don’t let them tell you I’m dead, Helen. We’re not dead. We’re right here. Jake’s throat burned. These weren’t last messages. These were men who still believed rescue was coming. The bell above the shop door chimed.

Jake looked up, expecting another reporter. Instead, an elderly woman stood there, backbone straight despite her walker, eyes sharp as broken glass. “You’re the Mitchell boy,” she said. It wasn’t a question. “Yes, ma’am.” “I’m Grace Sterling, Robert Sterling’s daughter. She moved into the shop with surprising speed.

I’ve been waiting 55 years for someone to find those recordings. Vern stood, offered his chair. She waved him off. I was 23 in 1950, she said. Home from college for Christmas break. December 15th. My father came home at dawn. He looked like he’d aged 10 years overnight. Went straight to his study and locked the door. I heard him crying. My father never cried, not even when mother died.

She pulled an envelope from her purse, hands liver spotted, but steady. He left me these, said if anyone ever asked about the mine to give them these. No one ever asked until now. Jake opened the envelope. Inside were photographs, black and white, grainy but clear. The first showed the mines’s command center, a room full of radio equipment, maps on the walls, men in suits clustered around a table.

One man was circled in red ink. William Brackenidge. The second photo was worse. It showed Brackenidge holding a radio microphone and in the background, clearly visible, a sign that read, “Emergency frequency, receiving transmission.” They were listening. They had proof the men were alive and they were listening. There’s more on the recordings,” Burn said quietly.

He’d been working while Jake and Grace talked, cataloging each hour. Hour 22. You need to hear this. Carl Mitchell’s voice, tired, but still strong. Mr. Brackenidge, I know you’re listening. We can hear your response team directly above us. They’re less than 40 ft away. We’ve been tapping on the pipes. The sound is carrying. Your engineers know exactly where we are.

Please, William, I’ve worked for you for 15 years. These men have families. It’s 3 days before Christmas. Please. Silence. Then, barely audible, someone crying in the background. That’s Eddie Coleman. Another voice said, “His wife just had a baby.” 2 weeks old. Grace Sterling’s face was stoned.

My father tried to override Bracken’s orders. tried to redirect the rescue teams. Bracken Ridge had him removed from the command center, threatened to have him arrested for interfering with emergency operations. Hour 28. Vern continued the playback. Roy Henderson. Now we’ve figured it out. The illegal mining under the river.

That’s what this is about, isn’t it? You hit water where you weren’t supposed to be digging and now you’re covering it up. But we won’t tell anyone. The men have agreed. We’ll say it was an accident. a natural pocket of water. We’ll sign whatever you want. Just get us out. Please, God, just get us out. Jake slammed his fist on the workbench. Tools jumped and scattered.

They offered to lie for him, he said. They offered to cover up his crime, and he still 32, Burn said, forwarding the wire. This is when it changes. Carl Mitchell again, but different now. Harder. Since you’re listening but not responding, I’m going to make a record for whoever finds this. We are in section 7, auxiliary chamber.

Coordinates on the mind map are L7, approximately 200 ft below surface. The water breach occurred at approximately 11:35 p.m. when Bracken Ridge Mining was illegally extracting coal from beneath the Suscuana River. Federal maps will show this area as offlimits. Compare them to Bracken Ridg’s extraction records. The evidence will be clear. A pause.

The following men are still alive as of a rustling sound. 8 a.m. December 16th, 1950. He began reading names again, but this time after each name, he added something personal. Roy Henderson has three kids and one on the way. Coaches little league at St. Mary’s. Dale Watson, wife Margaret, teaches school, just bought the house on Elm Street.

Jimmy Sullivan, mother is sick with cancer. He’s her only support. Frank Morrison has twin daughters, age seven. They’re in the Christmas pageant tomorrow night. On and on. 31 names. 31 lives, not just minors, fathers, sons, husbands, brothers. Real people being murdered in real time. While their killer listened. My father kept a journal, Grace said suddenly. I brought that, too. She pulled out a leather book.

December 16th, 1950. Jake read aloud. Bracken Ridge brought in federal inspectors at noon after the concrete had set, showed them the collapsed entrance. They never asked to check the emergency frequency. They never asked why we used 47 tons of concrete on a simple collapse. The Mitchell boy is still transmitting.

His voice is getting weaker, but he’s still trying. God help me. I can’t stand it. Hour 36. Vern said new voice on the recording. Weak, desperate. This is Dale Watson. Carl’s Carl’s resting, saving strength. We’ve decided to take turns. Keep the record going. The water’s at knee level now. We’ve moved everything to the highest point. Some of the men are praying.

Some are writing letters with pencil stubs on lunch bags. Jimmy Sullivan keeps saying his mother will think he abandoned her. She won’t understand. Can someone tell her? Can someone tell her he didn’t leave on purpose? Background voices murmuring. Then Dale again. We can hear the concrete setting. It makes a sound like like bones settling. That’s what we’re hearing. The tomb being sealed.

Grace Sterling stood. I need to show you something else. Both of you come with me. They followed her outside to her car. a pristine 1980s Cadillac. From the trunk, she pulled out a metal box. “My father went back,” she said. January 1951, after everything was sealed, after the families were paid off, he went back with recording equipment. Jake’s blood went cold.

What did he record? Nothing, Grace said. For 3 hours, he sat with his equipment pressed against the concrete seal. Nothing. But then just as he was leaving, he heard it. She pulled out another wire spool, this one marked differently. “We should go back inside to play this,” Burn said. “No,” Grace said. “You need to hear it out here in the open.

Because once you hear it, you’ll understand why my father drank himself to death by 1952.” She had a small batterypowered player in the box, old but functional. She threaded the wire with practiced ease. static long empty static then so faint it might have been imagination tapping rhythmic deliberate morse code SOS burn whispered that’s SOS January 15th 1951 Grace said a full month after the collapse someone was still alive down there tapping on the pipes my father said the pattern continued for 6 hours then stopped forever Jake couldn’t breathe couldn’t think. Someone had survived for a month in the dark, in the cold, in the

tomb Brackenidge had made. Who? He managed to ask. Grace shook her head. No way to know. But my father believed. He thought it might have been Carl. Your grandfather. He was the strongest, my father said. The most determined. If anyone could have rationed the food, the water, the carbide, could have survived on pure will alone.

Hour 40, Vern said suddenly, he’d brought the player outside. There’s something you need to hear. Carl’s voice, very weak now, but clear. If one of us survives longer than the others, he’s to keep signaling as long as possible. We’ve agreed. Whoever lasts longest has to try to leave proof we didn’t just give up. Frank Morrison knows Morse code.

He’s teaching it to the rest of us. Simple pattern. SOS. If you hear tapping after we stop talking, know that someone is still fighting, still trying. Don’t give up on us. The recording continued. Background voices teaching each other the pattern. Three short, three long, three short. Over and over, practicing for the unthinkable, being alone in the dark after the others were gone.

The families never knew about the January recording. Grace said my father couldn’t bear to tell them. To let them know someone might have been alive that long. The guilt killed him. He wrote in his journal that he could have saved them all on December 15th if he just had the courage to shoot William Brackenidge and take over the rescue. She pulled out one more photograph.

This was taken December 17th, 1950 at the sealed mine entrance. The photo showed a group of men in expensive suits, champagne glasses raised in a toast. William Brackenidge in the center smiling. Behind them, fresh concrete gleamed wet in the flash. “They’re toasting,” Jake said, his voice flat with disbelief. “They just buried 31 men alive, and they’re toasting.

” “The federal inspectors had just left,” Grace said. Bracken Ridge was celebrating. The illegal mining evidence was sealed away. The company was safe. Stock prices would remain stable. That’s my father on the edge of the photo, the only one not holding a glass.

Jake stared at the photo, at Bracken Ridg’s satisfied smile. At the champagne glasses catching the light, at the wet concrete that was still settling over 31 men who were at that very moment still breathing, still hoping, still tapping their names into the walls. “We’re going to destroy them,” Jake said quietly.

Every last person in this photo who’s still alive, every company that benefited, every official who looked the other way, they’re all going to pay. Grace Sterling smiled for the first time. A terrible satisfied expression. My father would like that. He spent two years gathering evidence before the drinking got too bad. I have it all. Every document, every receipt, every name. Hour 47.

Burn said the last transmission. Carl Mitchell’s voice, barely a whisper. This is the final broadcast from section 7. Our batteries are nearly dead. Most of the men are unconscious. We’ve carved our names into the walls as deep as we could. 31 names. Don’t forget them. Don’t let them disappear. We mattered. We lived.

We were betrayed by men we trusted, but we didn’t betray each other. Not once. We stayed together until the end. Tell our families we weren’t afraid. Tell them we talked about them constantly. Tell them the recording ended. Somewhere in town, church bells were ringing. It was Sunday. 55 years after 31 men realized they weren’t being rescued, their voices were finally being heard.

But Jake couldn’t shake the sound of that tapping. January 15th, 1951. Someone, maybe his grandfather, alone in the absolute darkness, still fighting, still signaling, still believing someone might care enough to listen. 30 days of darkness before the tapping stopped. “We need to open that mine,” Jake said. “We need to get them out.” “It’s been 55 years,” Vern said gently.

“I don’t care.” They scratched their names in the walls. “They’re still down there waiting. We’re going to bring them home.” Grace Sterling touched his arm. I know who can help. Some of the rescue crew from 1950 are still alive. They were ordered to stop digging. They’ve been waiting 55 years to finish the job. Grace Sterling’s living room looked like a war room.

Every surface was covered with documents, photographs, maps. She’d been preparing for this day for 55 years, and it showed. Jake stood at the dining table staring down at two maps of the Bracken Ridge Mine. One official stamped by the Federal Mining Commission, the other handdrawn in his grandfather’s careful script. The differences were staggering.

The official map shows the mine stopping here. Grace traced a finger along a thick black line. 300 yd from the river, safe, legal. But look at your grandfather’s map. Carl Mitchell had drawn the real tunnels in pencil annotated with dates and distances. The mine went another half mile directly under the Suscuana River.

They were stealing coal, Dennis said. He’d been silent since arriving at Grace’s house, but now his voice was hard with anger. Coal that belonged to the federal government. Coal they had no right to touch. Worth approximately 12 million in 1950, Grace said. She pulled out a ledger. Bracken Ridge Mining Company embossed on the cover. My father calculated it.

$12 million of stolen coal extracted over three years. All of it off the books. Vern was examining another document, a water table survey from 1949. Jesus Christ, they knew. Look at this. Extreme danger of water breach if mining continues eastward. Signed by Robert Sterling, chief engineer. My father begged them to stop. Grace said, “But Brackenidge had debts.

The company was bleeding money from a failed operation in Kentucky. The illegal coal was keeping them afloat.” Jake found another map. This one showing the rescue operation or what was supposed to be the rescue operation. Red arrows indicated where teams were sent. All of them in the wrong direction. They had them dig here. He pointed to section three and here section five.

But the men were in section 7. They knew exactly where they were, and they sent rescue teams everywhere else. It’s worse than that, Grace said. She pulled out a receipt. Look at the time stamp. It was a delivery order for industrial concrete, 47 tons. Timestamped 11:15 p.m. December 14th, 1950.

Jake’s stomach dropped. That’s That’s 30 minutes before the breach. They ordered the concrete before the accident even happened. Not an accident, Dennis said quietly. They knew the breach was coming. They felt it building and instead of evacuating, they prepared to cover it up. Grace nodded. My father’s journal from that day.

Bracken Ridge ordered concrete standing by. Says it’s for routine maintenance, but he’s had us monitoring the river wall all week. He knows what’s coming. Jake picked up a photograph from December 14th taken at 300 p.m. during shift change. 31 men heading into the mine for night shift. His grandfather in front hard hat tilted back laughing at something someone had said.

7 hours later, William Brackenidge would be ordering their tomb sealed. I found something else. Burn said he’d been going through a box of radio equipment Grace had provided. These are transcripts. Someone was writing down everything the men transmitted. The pages were typewritten neat and horrible. 12:47 a.m. Mitchell reports all me

n accounted for requests immediate assistance. 1:15 a.m. Mitchell reports hearing drilling in section 3. Corrects rescue team direction to section 7. 2:30 a.m. Henderson statesmen can hear concrete mixers and written in pen beside this entry in different handwriting. continue with seal WB William Bracken’s initials. He was reading their words as they begged for help, Jake said, and initializing orders to keep sealing them in. Grace pulled out another document, the payoff records.

Every family received $10,000, five times the standard death benefit. But look at the stipulation. Jake read the legal text. recipients acknowledge complete satisfaction with settlement and agreed to make no public statements regarding the circumstances of the accident in perpetuity. Buying silence, Dennis said.

My mother never told me about any payment because she never got it. Grace said she showed them another list. Three families refused to sign the silence agreement. Mitchell, Henderson, and Morrison. They got nothing. The company blacklisted them. Your grandmother Jake, she had to leave town to find work.

Took your father to Pittsburgh. That’s why I barely knew about grandpa. Jake said. Mom didn’t know the full story. Dad never talked about it. The families that took the money couldn’t talk about it, Burn said. And the ones who didn’t were driven out of town. Grace stood walked to a locked cabinet. There’s one more thing.

The thing my father died trying to forget. She pulled out a realto-re tape different from the wire recordings. 1951 Bracken Ridg’s private office. My father planted a recording device during a meeting. She had an old player set up. The tape crackled to life. The Mitchell woman came again. A secretary’s voice. Christ’s sake.

Bracken Rididge’s voice irritated. Give her another thousand. Tell her it’s charity from concerned citizens. She says she doesn’t want money. She wants to know where exactly her husband died. She wants to visit the spot. Tell her the entire mine is unstable, too dangerous. Tell her anything, just get rid of her. A door closing then Bracken Ridg’s voice again talking to someone else.

The families are breaking. Most of them took the money. The holdouts will cave eventually. What if someone talks? another man’s voice. What if they heard the transmissions? Who’d believe them? Grieving widows claiming they heard dead men on the radio. The FCC says it was interference from a ham radio operator in Scranton.

That’s the official story. But Sterling Sterling’s a drunk now. Crawled into a bottle after Christmas and hasn’t come out. No one will listen to him either. The federal inspector wants to check the site again. Show him the same sealed entrance. The concrete’s aged enough now. Looks like it’s been there for years. A pause. Then Bracken Ridge again. Colder.

Those men were dead the moment they saw where we were mining. Even if we’d pulled them out, they’d have talked. Federal investigation would have destroyed us. 31 men versus the livelihoods of 3,000 who depend on this company. I made the only choice I could. You think they’re dead by now? A long silence.

What does it matter? They’re 300 ft underground behind 50 ft of concrete. They might as well be on the moon. The tape ended. Grace turned it off with shaking hands. He justified it, Jake said, his voice hollow. He turned it into some kind of noble sacrifice. There’s more, Grace said. She pulled out engineering diagrams. These are the structural plans for the seal. Look at this. The diagram showed the mine entrance, but also something else. Ventilation shafts, three of them.

They sealed the main entrance, but these vents were capped, but not filled. Grace finished. My father noted it. Small air flow would have continued for days, maybe weeks. That’s how someone survived until January. That’s how they were able to tap on the pipes for so long. Jake traced the ventilation shafts on the map.

three narrow channels that could have been rescue routes. Instead, they were simply capped with steel plates, leaving the men below to suffocate slowly as the oxygen ran out. “Hour 39 of the recordings,” Vern said suddenly. He’d been listening while they talked. “Listen to this.” Roy Henderson’s voice weak but clear. “We found the ventilation shaft in the southeast corner.

The air is still flowing, just barely. If you could drop a rope. The shaft is only 18 in wide, but Jimmy Sullivan is small enough he could fit. Please, if anyone is listening, check the ventilation shafts. Southeast corner of section 7 were directly below. They’d known the trapped men had found a possible escape route and radioed its exact location, and Brackenidge had kept it instead. “My father tried,” Grace said, pulling out one more document.

January 2nd, 1951, he filed an injunction to reopen the mine for additional rescue attempts. A judge blocked it. The judge’s campaign had received $20,000 from Brackenidge two months earlier. Jake picked up the photo of Brackenidge toasting with champagne at the sealed mine, studied each face. Are any of these men still alive? Grace smiled grimly. Three.

Howard Brackenidge, William’s son, who’s now 81 and still CEO of Brackenidge Industries. Thomas Garrett, no relation to Tom, who died in the mine. He was the federal inspector who signed off on the false report. He’s 93 in a nursing home in Harrisburg. And James Wickham, the company lawyer who drew up the silence agreements. 91, retired in Florida. They’re about to have their retirement interrupted, Jake said.

Dennis stood, walked to the window. Outside, news vans were gathering. Someone had leaked that Grace Sterling had evidence. “It won’t bring them back,” he said quietly. “No,” Jake agreed. “But they’ve been waiting 55 years for justice, for someone to prove they weren’t just casualties of a mining accident.

They were murdered, and their murderers got rich off their deaths.” Grace pulled out one final item, a brass plaque tarnished with age. It read, “In memory of the 31 brave men lost in the Bracken Ridge mine disaster, December 14th, 1950. They gave their lives to the profession they loved.” “This is on the monument in town square,” she said. Brackenidge commissioned it himself.

Had the nerve to speak at the dedication, called them heroes who died doing what they loved. She dropped the plaque on the table with a clang. They didn’t give their lives. Their lives were stolen and they didn’t die doing what they loved. They died begging for help that was deliberately withheld.

It’s time the real monument was built. One that tells the truth. Jake looked at all the evidence spread across the table. Maps, recordings, receipts, photographs. 55 years of secrets finally exposed. But something was still missing. We need to get into that mine, he said. We need to find them. The physical evidence, their bodies, the scratched names, everything.

Without that, Bracken Ridg’s lawyers will call all of this circumstantial. The minds on private property now, Grace said. Bracken Ridge Industries still owns it. Then we go anyway, Jake said. Tonight, while the news has everyone distracted. That’s trespassing, Vern pointed out. Criminal trespassing. Jake picked up the photo of his grandfather laughing as he headed into his last shift.

Carl Mitchell, who’d spent 47 hours trying to save his men, who might have survived alone in the dark for 30 days, tapping SOS that no one would answer. Then I’ll trespass. They’ve been waiting 55 years. They’re not waiting another night. Dennis turned from the window. You’re not going alone, Dad. He was my father. I never knew him because of what they did. I’m going.

Vern stood. My father’s down there, too. Count me in. Grace Sterling smiled. My father always kept mining equipment in the garage. Industrial cutting tools that can handle concrete. He knew someday someone would need them. I think he’d be proud to know it’s today. Jake looked at the map one more time. Section 7. Auxiliary chamber. 200 ft below surface.

31 men who’d carved their names into the walls, determined not to disappear. “We’re coming, Grandpa,” he said quietly. “5 years late, but we’re finally coming.” The wire recordings played in the darkness of Vern’s van as they drove toward the abandoned mine. Jake had insisted on listening to all of it, every hour, every voice, every moment of his grandfather’s final two days.

They needed to understand what happened in those 47 hours to know what they were looking for. Hour 25. Carl Mitchell’s voice filled the van. Weaker now, but still organizing, still leading. We’ve divided the remaining water. Each man gets 2 ounces every 3 hours. The carbide is almost gone. We’ll be in darkness soon.

I’ve asked everyone to share one memory of sunlight, something to hold on to when the black comes. a younger voice trembling. I remember fishing with my dad at Hawk Creek. Sun was so bright on the water it hurt to look at. Another My daughter’s hair in summer goes golden like wheat. Jake’s throat closed as 31 men shared their sunlight memories, voices overlapping, creating a chorus of life in what was becoming a tomb.

Hour 29. Roy Henderson. Now the waters at waist level. We’ve moved to the highest shelf. Had to leave some things behind, but we saved the lunch pales. Don’t know why. Seems important to keep them. Dennis gripped the door handle hard enough to make it creek. Pull over. Dad, pull over. Vern stopped the van.

Dennis stumbled out, dropped to his knees in the grass, and vomited. Jake went after him, put a hand on his father’s shoulder. We don’t have to do this tonight, Jake said. Dennis wiped his mouth, stood slowly. Yes, we do. I’m 58 years old, Jake. I’ve spent my whole life wondering what his voice sounded like. Now I know.

He sounded capable, strong, even at the end. He looked at his son. We’re not stopping. They got back in the van. Grace had been silent, clutching a canvas bag of her father’s tools. Now she spoke. Play hour 35. Everyone needs to hear this part. Carl Mitchell’s voice again. Different now. Formal. This is foreman Carl Mitchell making an official report for whoever recovers this recording.

At approximately 0800 hours, December 16th, 1950, we observed concrete dust filtering through cracks in the chamber ceiling. This confirms the main entrance is being permanently sealed. We are being deliberately intombed. I want the record to be clear. We did not die in an accident. We are being murdered. A pause.

Then the following men are witnesses to this crime. He read all 31 names again, but this time each man responded, “Roy Henderson, I’m here. I’m alive. This is murder. Dale Watson, still breathing. This is murder. Jimmy Sullivan, age 19. They’re killing us. This is murder. On and on. 31 voices, each declaring their murder while it was happening.

Vern pulled into an overgrown access road. Ahead, barely visible in the moonlight. The sealed entrance to the Bracken Ridge Mine rose like a concrete tombstone. Yellow warning signs covered it. Danger. Unstable mine. No trespassing. Hour 38. The recording continued as they unloaded equipment. This is Frank Morrison. Carl’s resting, saving air.

We’ve been tapping on the pipes in Morris code like he taught us. SOS over and over. Maybe the sound will carry somewhere the radio won’t reach. Maybe someone will hear the sound of tapping in the background. Three short, three long, three short. Grace pulled out her father’s old surveying equipment. The ventilation shafts should be.

She checked a compass pointed northeast about 40 yards that way. They fought through decades of overgrowth. Jake carried the industrial concrete saw, its weight making his shoulders burn. The first ventilation shaft was exactly where Grace said it would be. A steel plate bolted into concrete, rusted but solid. Hour 41.

Eddie Coleman’s voice. Young, terrified. The carbide’s gone. We’re in the dark now. Complete dark. You can’t imagine. It’s not like closing your eyes. It’s like your eyes stop existing. Some of the men are seeing things. Lights that aren’t there. Their minds making up for what’s missing. Jake started the concrete saw.

The sound was deafening, but he didn’t care about stealth anymore. Let Brackenidge Industries call the police. Let them try to explain why they were stopping a rescue 55 years overdue. Hour 43. Carl again, barely a whisper. We’ve made a decision. Our bodies might not be recovered for years, decades maybe. So, we’re leaving proof. Each man is carving his name into the wall with whatever we have left.

Belt buckles, pocket knives, fingernails if necessary, deep as we can. So, you’ll know we were here. We existed. We fought. The concrete around the ventilation shaft cracked, split, fell away in chunks. The steel plate came loose, and Jake pulled it aside. A rush of stale air came up so foul he staggered back. That’s not just stale air, Vern said.

That’s death, Grace finished. 55 years of it. They lowered a work light on a rope. The shaft went down 20 ft before opening into a larger space. Jake could see reflections of water at the bottom. The chamber flooded eventually, Dennis said. Groundwater seepage over the decades. Hour 45. Multiple voices now.

Some praying, some singing hymns, some just talking to keep the dark at bay. Then Carl’s voice cutting through. If someone’s listening to this because they found our bodies know this, we could have lied. Could have agreed to cover up Bracken Ridg’s illegal mining to save ourselves. We refused. not from nobility. We just couldn’t let them get away with it. Couldn’t let our deaths fund their crimes.

So, if you’re listening to this, finish what we started. Expose them. Every last one of them. Jake rigged a harness and rope. I’m going down. Like hell, Dennis said. I’m his son. I’m going. I’m younger, Dad, and I know what we’re looking for. Before anyone could stop him, Jake swung into the shaft.

The walls were slick with moisture and mineral deposits. 20 ft down, he emerged into a larger space. His headlamp swept across horror. The auxiliary chamber was smaller than he’d imagined, maybe 30 ft across. The water was kneedeep, black, stagnant.

But above the waterline, covering every inch of wall he could see, were names scratched deep into the rock, overlapping, desperate. Carl Mitchell, husband to Rose, father to Dennis. Roy Henderson, tell my children I was brave. Dale Watson, Margaret, I love you, Jimmy Sullivan, mother, I’m sorry, over and over. 31 names with messages. Some had scratched more than once. The letters getting shakier, more desperate as time passed. Hour 46.

Carl’s voice from above, from the recorder. Vern was still playing. The waters rising faster. Some of the men have stopped responding. We’re running out of time. I want to say his voice broke. the first time in 46 hours. Rose, if you hear this, I love you, Dennis, my son. Grow up strong. Grow up kind. Don’t let what happened here make you hard.

And someone, anyone, remember us. Remember, we didn’t give up. Remember, we static. The batteries had died. Jake’s light found something else. In the corner, arranged in a perfect circle just above the waterline, were the lunch pales, 31 of them, placed with care, like an offering, like a final act of dignity in chaos. He waited over, his legs numb from the cold water.

The first pale had a name scratched on it. T Garrett. Inside, wrapped in waxed paper that had somehow survived, was a note. The pencil was faint but readable. Marcy, use the insurance money to get out of town. Don’t let them buy your silence. Love, Tom. Every pale had a note. 31 final messages protected in waxed paper, waiting 55 years to be found.

Jake’s lights swept the chamber again and found them. The bodies, or what remained? They were against the far wall above the eventual flood line, not scattered in panic, but arranged, sitting against the wall in a line, shoulder-to-shoulder. They’d faced the end together, deliberately with dignity. One body was separate from the others, positioned near the ventilation shaft, smaller than the rest.

“Jimmy Sullivan,” Jake whispered. He’d been trying to climb out. 19 years old, small enough to fit. He tried to reach the shaft that was being capped above him. His light caught something else. On the wall, separate from the names, carved larger and deeper than anything else, was a message. William Brackenidge knew we were alive. William Brackenidge murdered us. S.

December 14th to 17th, 1950. 31 men. This was not an accident. below it in different handwriting scratched with something sharp and deliberate. C Mitchell Foreman I stayed conscious longest. I heard you sealing us in. I heard you celebrating God sees what you did. December 20th, 1950. December 20th. Carl had survived 6 days.

Six days in the dark, in the cold, surrounded by the dead, still scratching truth into stone. Jake’s hands shook as he photographed everything. The names, the messages, the bodies, the lunch pales, the final accusation, evidence that would destroy Bracken Ridge Industries, that would rewrite history, that would finally, finally bring justice. Hour 47. Burns voice called down.

Jake, there’s a 47th hour. We missed it before. It’s not Carl. It’s I think it’s Bracken Ridge. Jake climbed up quickly, lungs burning from the foul air. Vern had found another wire spool labeled differently. He played it. William Brackeng’s voice, cold, matter of fact. December 17th, 1950. 2 a.m. for the company records, sealed separately.

The situation in section 7 has been contained. Federal inspectors have accepted the cave-in explanation. Families are being approached with settlements. The concrete will hold indefinitely. The illegal extraction zone is now permanently inaccessible. Company assets are protected. A pause. They stop transmitting 3 hours ago. It’s finished. Another pause. Longer.

Robert Sterling suggests we attempt recovery in a few years when attention has died down. I’ve overruled him. The bodies stay where they are. The evidence stays buried. This recording will be sealed in the company vault as insurance against future liability. The official story stands. 31 men died instantly in a cave-in. Heroes of American Industry.

The recording clicked off. Jake stood in the darkness covered in the muck of his grandfather’s tomb, holding the evidence of premeditated mass murder. “We’ve got them,” he said. “We’ve got everything.” Grace Sterling was crying. Dennis stood silent, staring at the mine entrance. Vern was already on his phone calling news stations.

There’s one more thing, Jake said. He pulled out one of the lunch pales he’d brought up. Carl Mitchell’s inside. Along with the note to Rose and Dennis was another piece of paper, fresher. It must have been written days later when Carl was alone in barely legible scratching. If my grandson finds this, I dreamed of you. In the dark, I dreamed I had a grandson.

Strong, determined, the kind of man who wouldn’t let injustice stand. I’m probably delirious. But if you’re real, if you’re reading this, you are my light in this darkness. You are my proof that something good came from my life. Find us. Free us. Tell the truth. Grandpa Carl. December 19th, 1950. Couch still fighting.

Jake held the note against his chest and sobbed. Dennis embraced his son. Both of them crying for the man they’d never known. Who had thought of them in his final hours, who had refused to surrender, even when surrender would have been mercy. In the distance, sirens wailed. Police probably, maybe FBI. It didn’t matter. They had the evidence. They had the truth. 31 men were about to come home.

The FBI had seized everything from the Bracken Ridge Industries headquarters before dawn. Jake watched from across the street as agents carried out box after box of documents, their evidence tape gleaming in the morning sun. But he wasn’t satisfied. The wire recordings had mentioned a command center, the place where Bracken Ridge had listened to the dying men.

It had to still exist somewhere. Found it, Vern said, approaching with a folder of archived newspapers. December 15th, 1950. The Hazelton Gazette. Rescue operations coordinated from Bracken Ridge Executive Mine Office. Address 1247 Mountain Road. That’s the old administrative building near Shaft 2. That’s been condemned for decades, Dennis said.

Roof partially collapsed in the 80s. Perfect place to hide evidence, Jake said. Grace Sterling pulled up in her Cadillac. Since their discovery three nights ago, she’d been working with federal prosecutors, but she looked exhausted. “They arrested Howard Brackenidge this morning,” she said.

“But his lawyers are already fighting the charges, saying the evidence is too old. Chain of custody issues. We need more.” “Then let’s go get it,” Jake said. The drive to the old administrative building took them through the abandoned part of Hazelton’s mining district. Empty company houses lined the streets, windows dark, porches collapsed.

This whole section of town had died when the mine closed. The building at 1247 Mountain Road was a two-story brick structure, its windows boarded, condemned signs plastered across the entrance. But Jake noticed something immediately. Fresh tire tracks in the overgrown parking lot. Someone’s been here recently, he said. They entered through a side door that had been pried open years ago.

Inside the building was a maze of empty offices, fallen ceiling tiles, and scattered furniture. But Jake was looking for something specific. A room with radio equipment, maps on the walls. They found it in the basement. The door was locked, but the wood was rotted. Dennis kicked it open. Inside, frozen in time like a museum of murder, was the command center. Radio equipment covered one wall.

1950s era transmitters and receivers, dials and switches. Maps of the mine covered every wall, marked with red X’s showing where rescue teams had been sent, all in the wrong places. But it was the corkboard that made Jake’s blood run cold. Pinned to it were photographs. Not just any photographs, pictures of the 31 miners, their company, ID photos.

Each one had a red line drawn through it with a time written beneath. Time of death, Grace whispered. They were marking when each man stopped talking. Carl Mitchell’s photo had the latest time. December 17th, 3:47 a.m. Final transmission. Jake pulled out his camera documenting everything. Then he saw it. A metal filing cabinet in the corner, locked, but not impregnable.

The prybar made quick work of it. Inside were transcripts, not just of the minors transmissions, but of the response team’s discussions. Someone had documented every word spoken in this room during those 47 hours. Jake read aloud. December 14th, 11:58 p.m. Brackenidge. How many heard the transmission? Sterling, just us. The emergency frequency is closed circuit.

Bracken Ridge, keep it that way. Start the concrete delivery. Sterling. Sir, they’re alive. All of them. Bracken Ridge. They’re dead men walking. They’ve seen the illegal shafts. Unknown voice. We could get them out and pay them to Bracken Ridge. You think 31 miners will keep quiet about federal crimes? Use your head. Dennis grabbed another transcript, his hands shaking.

December 15th, 4:00 a.m. Radio operator. Mitchell’s asking for his wife. wants to talk to her. Bracken Ridge. Absolutely not. Radio operator. Sir, just to say goodbye. Bracken Ridge. No contact. Any transmission from us could be traced later. Let them talk to the walls. They heard everything. Vern said, reading another page.

Every plea, every prayer, every message to their families, and they sat here discussing it like a business problem. Grace found something else. a leather journal hidden behind the filing cabinet. She opened it carefully. “It’s my father’s,” she said. “His real journal, not the one he kept at home.

” She read December 15th, 10:00 a.m. I’ve become complicit in mass murder. The men below are organizing their own funeral, scratching their names into walls while we pump concrete into their tomb. Bracken Ridge sits here eating sandwiches, checking his watch like he’s waiting for a train.

I’ve recorded everything on wire spools, hidden copies. If I die, someone needs to know what happened in this room. Jake found a box labeled evidence destroy after settlement. Inside were more photos, the rescue teams drilling in the wrong directions, obviously staged for the cameras. Bracken Ridge shaking hands with federal inspectors in front of the sealed mine. But one photo was different.

It showed the command center during the crisis. Men in suits clustered around the radio equipment and in the reflection of a window barely visible. The photographer himself. Robert Sterling. Grace said, “My father took this. He documented their crime while participating in it.” “There’s more equipment,” Dennis said from a closet. He pulled out a dusty box containing more wire recording spools.

“These are labeled differently. Outgoing transmissions.” Vern’s eyes widened. They did respond. They recorded their own responses. They didn’t have playback equipment here, but Jake carefully packed the spools. Then he noticed something else. A map with a route marked in pencil. It led from the mine to a location marked secondary containment.

What’s secondary containment? Jake asked. Grace studied the map. That’s that’s Riverside Cemetery. That’s where they built the memorial. The memorial is built over something, Dennis said slowly. What did they bury under it? They left the command center and drove to Riverside Cemetery.

The Bracken Ridge Mining Memorial stood on a hill overlooking the town, a black granite monument listing the names of the 31 dead men. Flowers lay at its base, fresh ones from the recent news coverage. It was built in summer 1951, Grace said. Bracken Ridge paid for everything, insisted on the location, the specific spot. Jake walked around the monument.

The foundation was much larger than necessary for a simple memorial. Concrete poured deep. “We need ground penetrating radar,” he said. “Something’s under here.” “Or,” Vern said, pointing to a maintenance shed. “We could check the cemetery records.” The shed was locked, but they were passed carrying about trespassing.

Inside, filing cabinets held burial records going back a century. Vern found 1951. Here he said special interment July 1951. Sealed concrete vault 8 ft by 8 ft x 6 ft deep. Contents mining equipment and personal effects from Bracken Ridge disaster. Sealed by order of William Brackenidge. Personal effects.

Jake said they buried evidence. His phone rang. It was the FBI agent handling the case. Mr. Mitchell, we need you to come to the federal building. Howard Bracken’s lawyer is claiming the wire recordings are fabricated. We need you to I’ll do you one better, Jake said. Bring an excavation team to Riverside Cemetery. We’re standing on top of more evidence.

3 hours later, the cemetery looked like an archaeological dig. The FBI had cordoned off the area, and workers carefully removed the memorial piece by piece. When they reached the concrete vault beneath, Jake could see it had been sealed with unusual care.

Multiple layers, reinforced steel, built to last forever. It took industrial equipment to break through. When they finally opened it, the FBI agents stepped back, letting Jake and the families go first. Inside the vault were 31 mining helmets, each tagged with a name. 31 broken watches, all stopped between 11:47 p.m. December 14th and 3:47 a.m.

December 17th, and 31 small boxes, each containing personal effects that should have been returned to families, wedding rings, pocket watches, photographs the men had carried. But there was more. A metal strong box sealed separately. Inside, William Brackenidge had left his insurance policy. detailed documentation of the entire coverup. Receipts, signed orders, even photographs of the men’s bodies taken through the ventilation shafts before they were sealed.

He’d kept proof of his own crime as protection against his co-conspirators. The FBI agent whistled low. This is a signed confession. He documented everything. Jake picked up his grandfather’s helmet. Inside the leather band was tucked a small photo. Rose Mitchell holding baby Dennis dated 1949. Carl had carried his family with him into the dark.

There’s one more spool, the agent said, lifting a wire recording from the bottom of the box. It’s labeled final statement WB January 1951. They played it right there in the cemetery with the town spreading below them. William Bracken’s voice older tired. This recording is my insurance. If anyone attempts to expose the events of December 1950, remember that I have documented every official who took bribes, every inspector who falsified reports, every town leader who accepted our money.

The list includes two senators, a federal judge, and the governor’s chief of staff. If I go down, northeastern Pennsylvania goes with me. A pause. The 31 men in that mine were heroes. I suppose they chose truth over life. Admirable if pointless. But I had 3,000 employees depending on Bracken Ridge Industries. I chose the many over the few.

History will judge me, but history is written by the survivors. And I survived. Another pause longer. Sterling’s boy keeps saying he can still hear tapping from the mine. Morse code SOS. I’ve had the ventilation shafts filled with additional concrete. If someone is still alive down there, well, they won’t be for long. This is my final word on the matter. The mine stays sealed. The truth stays buried. The company survives. The recording ended.

He knew, Dennis said, his voice breaking. He knew someone might still be alive, and he sealed the vents anyway. January 15th, Jake said quietly. Grace’s father heard the tapping on January 15th. Brackenidge had the vents filled on January 10th. The tapping Robert Sterling heard it was through solid concrete.

Someone, maybe my grandfather, was still tapping SOS through solid concrete 5 days after the vents were sealed. The FBI agent was on his phone calling prosecutors. We have enough to charge Howard Brackenidge with conspiracy to commit murder, even if he was only 26 when it happened. He inherited this evidence. He knew. He kept it hidden. But Jake wasn’t listening. He was looking at the recovered evidence, the carefully preserved proof of mass murder.

William Brackenidge had saved it all, thinking it protected him. Instead, it would destroy everything he’d built. The sun was setting over Hazelton, painting the old mining district gold. Somewhere beneath their feet, 31 men still waited in their tomb. But their voices had finally been heard. Their truth was finally free.

“We need to have a proper funeral,” Jake said. “Once they’re brought up, all 31 buried properly with their real stories told.” Grace Sterling nodded. “My father would want to be there.” His ashes, I mean, he never forgave himself for his role. Maybe this will let him rest. As they left the cemetery, Jake noticed people gathering at the fence.

Families of the dead miners, some he recognized from old photos. They stood silent, watching, waiting. 55 years of questions were finally being answered. But one question remained. When they opened section 7, what else would they find? What other messages had the dying men left in those final days? Tomorrow, the real excavation would begin.

Tomorrow, 31 men would finally come home. The mine entrance loomed in the darkness, concrete seal intact, despite 55 years of weather. Jake, Dennis, Vern, and Grace had arrived at 2:00 a.m. with industrial cutting equipment from Grace’s father’s collection. No permits, no permission, just determination. This is illegal, Burn said again. But he was already unloading the concrete saw.

They’ve been illegal for 55 years, Jake replied. We’re just balancing the scales. The concrete was harder than expected. Industrial-grade, poured thick. It took 3 hours of cutting to breach it, the noise splitting the night. Jake kept expecting police, but none came. Maybe Grace had made some calls. Maybe God was finally paying attention.

When the hole was wide enough, Jake rigged a harness and rope. The shaft dropped into blackness. I’m going down, he said. Jake, my grandfather, my risk. He descended through the jagged concrete opening, headlamp cutting through darkness that hadn’t been disturbed in 55 years. 20 ft, 30. Then his boots hit water. The auxiliary chamber was smaller than he’d imagined.

Knee deep water, black and still. But his light caught something that made his breath stop. The walls. Every inch above the waterline was covered in scratched names, deep gouges in stone overlapping desperate. Carl Mitchell, husband to Rose, father to Dennis Roy Henderson. Tell my children I was brave. Jimmy Sullivan, mother, I’m sorry.

31 names with messages carved by fingernails and belt buckles and anything they could find. His light swept left and found them. The bodies were against the far wall above what must have been the eventual flood line. Not scattered in panic, but arranged, sitting in a line, shouldertosh shoulder, facing the entrance they’d known would be sealed. Waiting with dignity for a rescue that never came.

One body sat apart from the others near the center. Even after 55 years, Jake could tell from the position from the foreman’s helmet still on the skull. Carl Mitchell. He’d positioned himself in front of his men, facing the entrance as if standing guard. In the corner, arranged in a perfect circle just above the waterline, were the lunch pales, 31 of them, placed with care.

Jake waited over, his legs numb from the cold water. The first pale he opened had a name scratched on it. T Garrett. Inside, wrapped in waxed paper that had somehow survived, was a note. Marcy, don’t let them buy your silence. Tom. Every pale held a note. 31 final messages protected and waiting. But it was Carl Mitchell’s pale that made Jake’s hands shake.

Along with the note to Rose and Dennis, there was another paper written later when Carl must have been alone. If my grandson finds this, I dreamed of you. In the dark, I dreamed I had a grandson. Strong, determined. You are my light in this darkness. Find us. Free us. Tell the truth. Grandpa Carl. December 19th, 1950. Still fighting, Jake photographed everything.

The bodies, the carved names, the lunch pales, the messages. Evidence that would destroy Brackenidge Industries. Then his light caught the largest carving separate from the names. William Brackenidge knew we were alive. William Brackenidge murdered us 31 men. This was not an accident. Below it in different scratches.

See Mitchell, I stayed conscious longest. I heard you sealing us in God Sees What You Did December 20th, 1950. 6 days. Carl had survived 6 days near another body, smaller, younger, more scratching. J. Sullivan, January 10th, 1951. Still here, still tapping. Mom, I’m sorry.

The 19-year-old had lived almost a month in absolute darkness with 30 corpses, still tapping SOS that no one would hear. Jake, Dennis called down. Police are coming. Jake grabbed Carl’s lunch pail and climbed quickly. As sirens approached, he looked back at the hole they’d cut. 31 men were visible now. Found witnessed. Let them arrest us,” Jake said, holding his grandfather’s final note. “We got what we came for. Proof they didn’t just die.

They were murdered while begging for help, and we can finally bring them home.” The police cars pulled up, lights flashing. But Jake noticed the FBI was with them. Someone had made calls. The real excavation would begin at dawn, 55 years late, but the rescue had finally come. The excavation of section 7 had taken three weeks.

Jake stood at the edge of the open mineshaft, watching as the first body bag was raised to the surface. The FBI had wanted to handle it all, but the families had fought for the right to be present, to witness, to receive their dead properly after 55 years. The 31 bodies had been found exactly as Jake had first seen them, arranged against the wall, shouldertoshoulder, with one exception.

Jimmy Sullivan, the 19-year-old who’d tried to climb the ventilation shaft, whose fingernails had been torn away from clawing at the sealed steel plate above. But it was what they found with Carl Mitchell’s body that changed everything. Mr. Mitchell, the forensic technician called, “You need to see this.” Jake descended into the mine one last time.

His grandfather’s body was still where they’d found him, separate from the others, positioned near a wall covered with his final messages. In his lap, protected by his jacket, and wrapped in what looked like pages torn from a maintenance log book, was a bundle of papers. The technician carefully lifted them, placed them in an evidence bag.

He protected these deliberately, wrapped them in waterproof cloth from a equipment tarp, then kept them under his jacket. Whatever these are, he wanted them preserved. In the temporary forensics tent, they carefully separated the pages. Jake, Dennis, and Grace watched as the technician used special lights and preservation techniques to make the faded pencil visible. The first page was dated December 17th, 1950. 4 a.m.

Just minutes after the batteries had died, after the last radio transmission, Carl Mitchell’s handwriting, shaky but clear. The radio is dead. The men are unconscious or sleeping. I remain awake. Someone must witness. Someone must record. I will write until I cannot. Roy Henderson died at 3:15 a.m. He was talking about his children. Said their names over and over.

I promise to remember them. Thomas, age seven. Margaret, age 5. Susan, age three. Baby unnamed. Do Christmas. Jake’s throat burned as his grandfather documented each death. Each man’s final words. Final thoughts. December 18th. Noon. I think. No way to tell time except by counting. Dale Watson died holding a photo of his wife. Kissed it before he went. Asked me to tell her he wasn’t afraid. He was afraid. We all are.

But the lie might comfort her. Frank Morrison went quietly, carved his daughter’s initials into his palm with a nail. Said Pain reminded him he was still alive, still their father. I am now alone with 27 dead men. The water has receded some. I’ve moved the bodies above the water line. They deserved dignity.

Dennis covered his face, shoulders shaking. Grace gripped Jake’s arm hard enough to hurt. The next pages were different. Carl had started writing smaller, conserving paper. December 19th. Found Jimmy Sullivan’s hidden stash of carbide. The boy was saving it, probably hoping to signal if rescue came. Used it to see while I arranged the men properly.

They will not be found scattered like animals. They’ll be found as they were. Brothers. I’ve been thinking about Dennis, my son. He’ll grow up without me. Rose is strong. She’ll remarry. I hope he’s kind to my boy. I hope Dennis knows his father loved him. I hope he knows I thought of him every hour down here. The tapping continues. I’ve been doing it so long it’s automatic now. SOS SOS SOS.

My knuckles are raw, but the pain keeps me focused. Someone might hear. Someone might come. then dated December 20th. William Brackenidge, I know you’ll read this someday. Your guilt will make you check. You’ll want to know what we said about you in the dark. Here it is. We forgave you, not for your sake, for hours.

Hate takes energy, and we needed our energy to survive. But forgiveness is not absolution. You are a murderer. You killed 31 men for money. God sees. History will see. your children will see. To whoever finds this, we could have saved ourselves by agreeing to Brackeng’s crimes. We refused, not from nobility, but from knowing that more men would die in those illegal tunnels. Our silence would have killed others.

So, we chose to die speaking truth. The next section was different. The handwriting was worse, wandering across the page. December 21st. I think the dark is complete. The carbide is gone. I write by touch, hoping these words are legible. The human mind isn’t meant for absolute darkness. I see things. Lights that aren’t there. Faces of the dead.

Rose sometimes standing in the corner telling me to come home. I know she’s not real, but I talk to her anyway. I’ve been thinking about legacy. What we leave behind. I’m leaving behind a son who will never know me. These words, the truth on these walls. Is it enough? How do you compress a life into scratches on stone? Jake turned the page. The writing was larger now.

Desperate. December 22nd. Water rising again. Moved to highest point. Can barely feel my hands. Still tapping. Always tapping. Someone might hear. Someone might come. The dead men watch me. I arrange and rearrange them. They deserve dignity. We all deserve dignity. I dreamed I had a grandson. Strange dream for a dying man, but clear. A young man, strong, determined.

He was reading these words. He was bringing us home. Probably delusion from lack of oxygen, but a comfort. If your real grandson know that you were my light in this darkness. That was the passage Jake had found in the lunch pale. But there was more. December 23rd. 7 days. Seven days in the dark with the dead.

I’ve carved everyone’s names again. Deeper. The stone is hard, but I have nothing but time. Each name a life. Each life a story. The stone will remember even if the world forgets. Can hear something. Drilling? No. Different. Softer. Concrete being poured. They’re sealing the ventilation shafts. The last air will go soon, but I keep tapping.

SOS SOS. Someone might hear. The next page was barely legible. The writing wandering wildly. December 24th, Christmas Eve. Rose will be at her mother’s. She makes ham on Christmas Eve, turkey on Christmas. Dennis will get the rocking horse I built hidden in McGra’s barn. Someone tell her the boy should have his gift.

The dead men and I are having Christmas dinner. Imaginary feast. Morrison says the turkeyy’s too dry. Henderson wants more gravy. We laugh. The dead men laugh with me in the dark. Is this madness? Does it matter? Still tapping. Knuckles bleeding but still tapping. It’s my heartbeat now. SOS. I exist. I exist. I exist. Then the last entry.

The writing so faint they needed special equipment to read it. December 25th, 1950 Christmas. Alone, always alone, but also not alone. 30 brothers sleep around me. We came down together. We’ll leave together someday. To Rose, I loved you from the moment I saw you at the church social. You wore a yellow dress. You laughed at my terrible jokes. Thank you for Dennis.

Thank you for 7 years of morning coffee and evening conversations. Thank you for loving a simple minor. To Dennis, be good to your mother. Be kind. Be brave. Be better than the men who did this to us. I’m proud of you, son, for the man you’ll become. To William Brackenidge, I forgive you. But forgiveness is not forgetting. These words are my witness against you. You thought you were buying 31 men.

You were buying 31 ghosts. We will haunt your legacy forever. I stop writing now. Stop tapping. Stopping. The dark is complete and I am. The sentence ended midword. The tent was silent except for Dennis’s broken sobbing. Jake held the pages like they were made of gold. His grandfather had survived 11 days. 11 days in absolute darkness, surrounded by death.