‘Come With Me,’ Said The U.S. Soldier To The German Woman In Ruined Berlin….

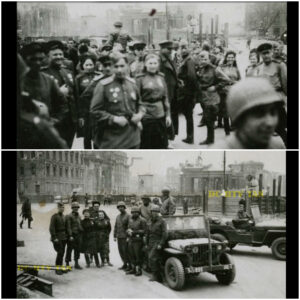

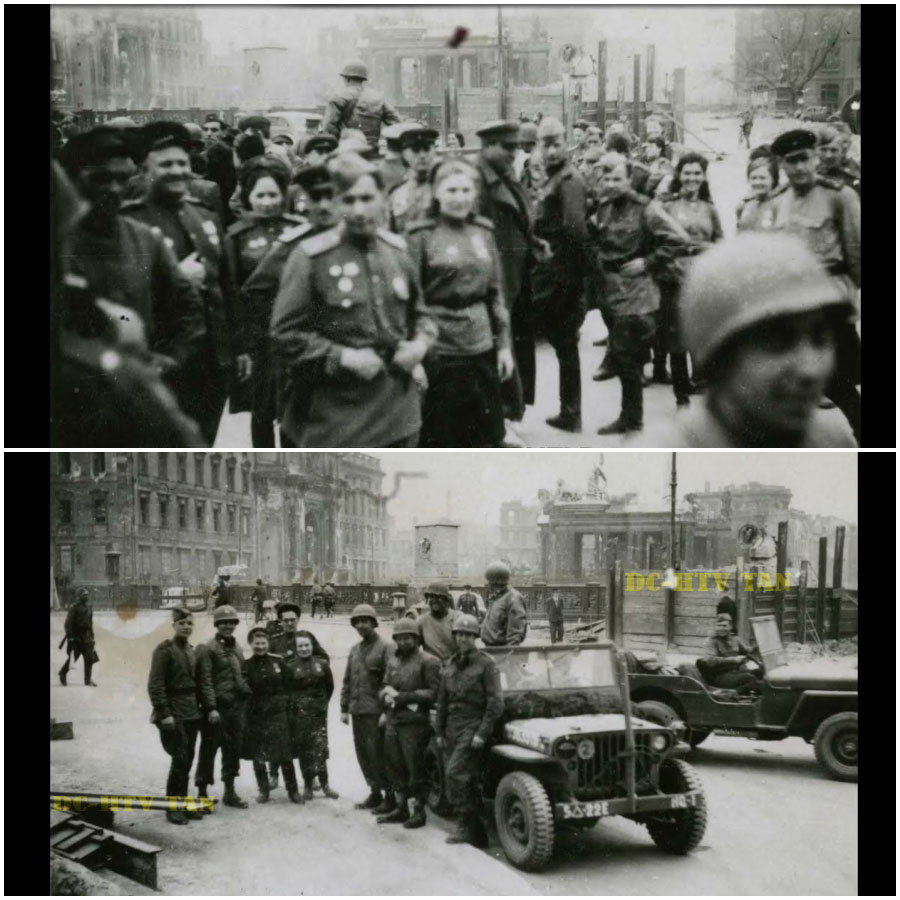

Berlin, May 1945. The city wasn’t destroyed. It was erased. Roofs collapsed. Walls split. The air thick with lime dust, smoke, and decay. The smell of death mixed with rain and plaster. People moved like shadows through streets of rubble. Silent, slow, eyes gray from hunger and fear.

On May 3rd, the first American armored units entered the western districts. A Sherman tank stalled at Vittenberg Plats. No fuel left. The soldiers climbed out, lit cigarettes, and stared at the ruins. From a nearby doorway, a barefoot woman appeared, waving a white sheet tied to a broom handle. She didn’t speak. One soldier handed her a tin of rations.

She took it with both hands like a sacred object. Of Berlin’s 4.3 million pre-war residents, barely 2 million remained. Half were women. 400,000 children, 60,000 elderly, and countless uncounted, buried, missing, vanished somewhere between the elder and the odor. The US Army called them displaced persons. They called themselves alive. Orders were strict.

No fratoninization, no private contact with civilians. But orders don’t survive hunger. A can of spam meant safety. A cigarette meant a favor. In the ruins, everything had a price. The Americans came searching for archives, officers, documents. What they found were basement full of survivors.

Women and children wrapped in blankets, eyes empty, faces white with plaster dust. A sergeant wrote later in his log, “We came as victors. We arrived as witnesses to extinction. The tear garden park had turned into pasture. Horses grazed among bomb craters. There was no power, no clean water, no transport. People burned books and furniture for heat.

Whole families lived in cellars lit by candles made from melted soap. By day, American patrols mapped sectors. By night they shared coffee and canned meat with those who dared to approach. Every exchange blurred the line between occupation and mercy. One of those women was Margaret Went, 27, former typist at Seammens.

Her husband was killed at Ceilo Heights two weeks earlier. On the evening of May 4th, she approached a US jeep at Kur Fendam and asked in broken English, “You from America?” “Yes, then I live.” She began cleaning the soldiers quarters, sweeping floors, washing uniforms, sometimes just sitting near their stove. In return, they gave her food.

Within a week, they called her Maggie. The official police log for May listed 1,482 disciplinary incidents, civilian contact in the American sector. The real number was likely 10 times higher. Each case was filed, investigated, and quietly forgotten. Berlin existed in a new kind of balance.

The conquerors didn’t feel victorious. The conquered didn’t feel guilty. Between them stretched a silence that replaced morality with necessity. When an American said, “Come with me.” It wasn’t romance. It was survival. It meant warmth, bread, protection for one more night. That was the new language of peace.

Short, hungry sentences exchanged in the ashes of a dead empire. Berlin slept without lights. After sunset, the city disappeared, replaced by shadows and memory. The blackout wasn’t enforced. It was total. No electricity, no street lamps, no trains, only the faint red glow of smoldering ruins. People navigated by smell and habit. The official curfew began at 9.

Patrols moved through streets that no longer had names. Their orders were simple. Maintain order. Report incidents. avoid contact. But order meant nothing in a place without law. At 10:15 p.m., Sergeant Willard Dunn noted in his patrol book. Light seen behind curtains. Canstraasa 71. Checked. One woman, two children, candlestub, said she was waiting for her husband.

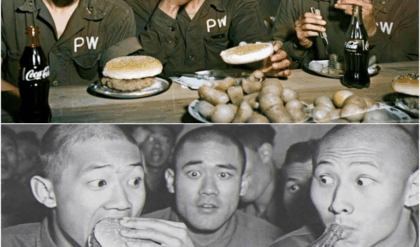

Didn’t ask which army he was in. By then, most of Berlin’s surviving men were either prisoners or corpses. The women handled the negotiations of existence. They lined up at American kitchens and whispered in English they barely knew. Bread, please. Work, help. The first supply convoys reached the US sector on May 5th.

19 tons of powdered milk, 11 of wheat flour, 2,000 gallons of kerosene. The rations were intended for soldiers only, but within hours portions vanished into side streets and basement. Cigarettes replaced coins. Coffee replaced loyalty. Margaret Vent understood faster than most. She started translating between locals and American quarter masters.

Simple words, gestures, lists. She wasn’t paid officially, but soldiers handed her chocolate, sugar cubes, soap. She carried them home wrapped in newspaper-like treasure. On May 6th, the order arrived from Sheriff headquarters. All fratonization with enemy nationals remains strictly forbidden under penalty of court marshall.

The same day, military police reported 300 new violations. Berlin’s moral structure collapsed in silence. Hunger dictated its own hierarchy. One cigarette could buy a kiss. a loaf of bread or an hour of safety from another patrol. The city turned into a marketplace of fear. A diary recovered years later from a bomb department read, “They came not as monsters, but as men with food, and that’s what breaks you.

” The American soldiers didn’t think of themselves as occupiers. They were young, restless, drunk on adrenaline and relief. They handed out rations to women twice their age, shared blankets, sometimes laughter, then in the morning wrote it all down as incident report. Margaret’s nights blurred into routine. Scrubbing, washing, sleeping beside her jacket to stay warm.

She learned the rhythm of army life. Real at dawn, rations at noon, curfew at dusk. The soldiers joked, played cards, argued about going home. She listened, smiled when they did, ate when they let her. The city adapted. Black markets grew in sellers and tram stations. A gold ring was worth 14 pounds of flour. A bar of soap, half a kilo of coal.

Every object translated into calories. Even human attention became a currency. Margarette began keeping notes again. the habit of a cler who once recorded factory shipments. Only now her entries were trades. Two eggs, one soap, bread, one hour washing, meat, one body. When asked months later why she wrote it down, she said, “Because numbers don’t lie, even when people do.

” By miday, Berlin was divided into invisible zones of barter. Soviet rations on one side, American cigarettes on the other. Between them, women walked miles each night carrying baskets filled with whatever could be exchanged. Soldiers called them market girls. Civilians called them the moving ones. A phrase began circulating among the Americans. Come with me.

They said it half jokingly, half command. It was the new password of power. Short, universal, undeniable. In a city of ruins, everyone followed someone. By the end of May, the first flowers appeared between shell craters. The war was over, but the peace that followed it had no language yet, only gestures of survival. By June 1945, Berlin was starving with discipline.

The city’s average daily ration for civilians had fallen below 950 calories. The US Army Medical Corps reported outbreaks of typhus in Moabitet and Wedding. Their solution was DDT sprayed from jeeps like snow covering children, bread stalls, and corpses alike. It worked against lice, not despair. In the American sector, every object became negotiable.

A gold watch equaled 14 pounds of flour. A wedding ring equaled two cans of spam. One night with an American soldier could mean a week’s worth of rations. Nothing was theft anymore. It was arithmetic. Margaret went wrote her own math in a notebook once used for seaman’s invoices. Flower, two cigarettes. Soup, one smile. Bed, three cans.

Her handwriting stayed precise, the tone detached. Numbers gave control where morality could not. US intelligence officers called this phase economic reorientation. The truth was simpler. Survival through trade. Cigarettes were the new currency and soldiers were its bankers. At Tear Garden, Sergeant Dunn’s patrol noted women approaching supply trucks in organized groups.

Organized was the wrong word. It was instinct. They waited for engines to stop. Hands already out, not begging, just calculating. He wrote, “You start thinking about what hunger costs when you realize it’s cheaper than guilt. The Americans confiscated German money. Worthless Reich’s marks printed by the millions.

Cigarettes took over completely. A lucky strike equaled 10 marks. A pack could buy a family’s week. By midsummer, entire underground markets formed around army depots. One report estimated 3.1 tons of goods traded daily in unofficial exchange. Margaret adapted faster than most. She found an interpreter’s job at Templehof, translating for quarter masters.

Her payment wasn’t in cash. Chocolate, soap, coffee, small things that smelled of civilization. She shared some with her neighbors, who in turn shared rumors. In a city without laws, kindness was also currency. The Red Army looted the east side relentlessly. Factories stripped, machines shipped to Moscow by the ton.

The Americans pretended to enforce discipline, but theft ran both ways. Soldiers traded gasoline for gold, ammunition for whiskey, rations for company. The official term was local adjustment. One internal memorandum from the counter intelligence corps dated July 1945 stated bluntly, “Fratonization is uncontrollable.

Prevention no longer feasible. Recommend silent tolerance.” At night, the markets became social gatherings. Women came with baskets. Soldiers came with duffles. Someone played an accordion. Someone laughed too loud. Deals were struck with gestures more than words. Morality faded into routine. Berlin’s churches filled again, not for worship, but for food lines.

Priests distributed powdered milk under crucifixes made from salvaged iron. In sermons, they didn’t speak of forgiveness, only endurance. Margaret’s American friend, Private Keller, helped her once when her ration card was stolen. He forged another, copying an officer’s signature by memory. She asked why. He said, “You do the same for me.” She didn’t answer.

By late July, mortality dropped for the first time since the surrender. People were learning to live on less, to measure success in grams. But with each passing week, something invisible eroded. The sense that life might one day return to what it was. The official Allied report for that summer reads, “Civilian order restored.

Morale acceptable.” The streets told a different story. Kids scavenged in uniform pockets. Women cut their hair to trade it for soap. Men came back from camps thin as wires, looking for homes that no longer existed. Berlin wasn’t rebuilding. It was learning to function while broken. And through it all, the same phrase echoed through stairwells, alleys, and checkpoints.

Come with me. Sometimes it meant food. Sometimes it meant shelter. Sometimes it meant nothing at all. But in a city built on ashes, it was the only sentence still alive. Autumn 1945. The air over Berlin turned to dust again. But now it was organized. What hunger had created. Bureaucracy perfected.

Every building with a roof became an office. Every survivor a file. Americans called it reconstruction. The Germans called it routine. The Reichs mark was worthless. inflation above 600%. Cigarettes had replaced paper money entirely. One lucky strike equaled 10 marks. One carton could buy a bicycle. The real power belonged not to generals or politicians, but to anyone with access to American supply depots.

A cook with a key could feed a family. A driver with a truck could control a district. Private Keller was assigned to logistics at Tear Garden Depot. His daily records listed cargo in tons, 23 of flour, seven of coffee, four of gasoline, and miscellaneous humanitarian goods. The goods never reached their destinations, some ended in the black market, some in officers quarters, some in the hands of women waiting outside the fence.

Official loss ratio 18%. Unofficially, no one bothered counting anymore. Margaret saw the system forming and learned to survive within it. She was now an interpreter for the Economic Division, translating German requests for American permits. Every conversation began the same way. We need paper. Everyone ended the same way.

We’ll see what we can do. She discovered the real currency wasn’t food anymore. It was permission. A new class of Berliners appeared. The intermediaries. Not soldiers, not civilians. People who could translate between chaos and order. They wore American jackets over German shirts. Spoke both languages with equal cynicism. Margaret became one of them.

The Americans liked efficiency. The Germans liked the illusion of rules. Together, they built a machine that ran on signatures instead of fuel. In three months, the city issued 112,000 new ration cards, 34,000 work permits, 5,000 marriage licenses, and countless forged documents that look just as official as the real ones.

In August, an American major named John Tully wrote in his field report, “We are maintaining order by manufacturing paperwork faster than the Germans can eat.” The contradiction didn’t matter. On paper, Berlin was healing. On the ground, it was feeding on itself. Margaret used her position to help others, sometimes honestly, sometimes not.

She arranged passes for neighbors, filed fake medical exemptions, even hid a few wanted names in translation errors. When Keller confronted her, she said, “The truth doesn’t feed anyone.” He didn’t argue. At the same time, the Soviets stripped the eastern factories bare. From the AEG and Seaman’s plants alone, 380,000 tons of equipment were shipped east by train.

The Americans, unwilling to appear weak, quietly began their own extraction under the name Operation Paperclip. Scientists and engineers disappeared overnight. Flown to bases in Texas and Ohio. In official records, they were listed as missing. The people left behind learned silence.

You didn’t ask where someone went. You didn’t ask why. Berlin existed between two truths. One printed in newspapers, the other whispered in kitchens. A German phrase spread through the city that autumn. Bessa kind of frogen. Better not to ask. By September, the first cafes reopened, serving acorn coffee and black bread.

They filled with men in borrowed uniforms and women in borrowed smiles. Outside the rubble women kept working passing bricks handto hand 12 hours a day 7 days a week. The posters said offbound nishclen build. Don’t complain. They did both anyway. For the Americans life settled into rhythm. Inspections, convoys, reports.

For the Germans, it settled into endurance. The black markets didn’t disappear. They went underground. The cigarettes were now just symbols of something larger. A system built entirely on unspoken bargains. And in that silence, the phrase remained. It outlived regulations, papers, orders. Soldiers said it softly. Civilians repeated it with resignation.

Come with me. Sometimes it was an invitation. Sometimes a command, sometimes a warning, but it always meant the same thing. Someone had something the other needed. Spring 1946. The ruins began to bloom again, but the soil was still poisoned by memory. The rubble women kept passing bricks like metronomes.

12 hours a day, 70 g of bread per shift. Officially, Berlin was rebuilding. In reality, it was rehearsing a version of hope it no longer believed in. The Americans reported progress in numbers. 81 million cubic meters of debris removed. 12,000 power lines repaired. 48 schools reopened. The statistics looked clean. The air still smelled like smoke and rain.

Margaret worked now for the public information division, translating propaganda scripts for news reels. Every line began with the same phrase, “The new Berlin rises.” She read it so often that the words lost weight. The films showed children smiling beside American soldiers, cafes reopening, church bells ringing. None of them mentioned starvation, prostitution, or the bodies dug up when the frost melted.

She’d once written everything in her notebook. Now she stopped. Paper had become dangerous. A single sentence could decide your future. Private Keller was transferred to the information service, driving film reels between districts. His job was to deliver images of peace. He’d seen enough of the real city to know they were lies, but lies were lighter cargo.

One day in a theater on Potama Plats, he watched the new real play. It showed women sweeping rubble, soldiers handing out chocolate, children waving at the camera. The narrator’s voice said, “Democracy rebuilds what tyranny destroyed.” The audience sat in silence. When the lights came up, no one clapped.

Someone whispered, “They film us like animals.” Keller left before the next showing. By summer, the city had learned to function like a machine again. Efficient, exhausted, obedient. The black markets became permanent. The cigarettes turned into Deutsche marks. People with connections became officials. People without them became ghosts. Margaret saw it all from behind her desk.

Stamping forms for work permits, marriage licenses, relocation passes. The names changed. The hunger stayed. Once she saw Keller’s name on a file, transfer to Frankfurt. She didn’t call him. There was nothing left to say. The official documents described her as translator, reliable, cooperative. The reality was simpler. A survivor who’ traded everything except her silence.

The Americans began leaving in waves. New faces replaced old ones. Trucks rolled out of the city, loaded with typewriters, spare parts, and stolen paintings. The soldiers left behind tried to believe they’d done something noble. They hadn’t conquered evil. They just inherited its ruins. In the final Allied Report of 1946, a single line summarized the entire experiment.

Reconstruction achieved through managed memory. The phrase was perfect. Nothing about Berlin was whole, but on paper it was finished. Winter came early that year. Keller, now stationed near Frankfurt, received his discharge papers. He carried nothing home except his uniform, his notebook, and a small photograph, blurry, overexposed, of a woman standing among ruins, holding a white bed sheet like a flag.

He didn’t remember when he took it. Back in Berlin, Margaret walked through Kurenam as snow began to fall again. The city had lights now, weak, yellow, trembling, but it was enough to see her breath. A group of American trucks passed slowly, engines humming. She stopped, watched them disappear, and whispered something to herself that no one heard.

History would later call that period peace. The archives would list it as postwar normalization. But to the people who lived it, peace wasn’t a date. It was an echo somewhere in the ruins. The same words that began everything still hung in the air. Half command, half mercy. Come with me. And the city, tired of choosing sides, finally obeyed.