German POWs Couldn’t Believe Ice Cream And Coca-Cola in American Prison Camps…

Summer 1943. Camp Crossville, Tennessee. The brown liquid fizzing in the bottle mesmerized the German soldier who had never seen anything like it. After 2 years fighting in North Africa, subsisting on hard biscuits and Ursat’s coffee. This sweet carbonated drink called Coca-Cola represented impossibility made real.

It cost 5 cents from the camp canteen, the same price guards informed him that American children paid with their allowances. Across American prison camps that summer, 371,683 German PS would confront a reality that contradicted everything Nazi propaganda had taught them about American weakness.

They discovered a nation where ice cream was routine dessert, where soft drinks were everyday beverages, where candy bars were so common that guards gave them away. These simple foods, treats that most German children had never tasted, would systematically demolish Nazi ideology more effectively than any propaganda program.

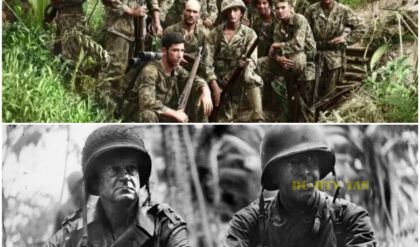

The mathematics of abundance were being written in sugar and carbonation, in chocolate and ice cream, revealing an American industrial capacity that rendered German deprivation not noble sacrifice, but needless suffering. What began as amazement at American confections would evolve into complete psychological transformation. The desert’s end. The Africa Cors surrender in Tunisia during May 1943 brought approximately 250,000 German and Italian soldiers into Allied captivity.

These veteran desert fighters who had pushed the British back to Egypt under RML’s leadership expected harsh treatment as prisoners. Nazi propaganda had prepared them for American brutality and starvation. Instead, within hours of surrender, they encountered American Krations.

These field rations, which American soldiers routinely complained about, contained treasures: crackers, processed cheese, candy, fruit bars, instant coffee, sugar tablets, and cigarettes. German soldiers who had survived on minimal rations for months treated these emergency meals as feasts. According to military records, at the processing camps in North Africa, the US Army served pancakes with syrup, fresh eggs, and milk, foods that had vanished from German military rations years earlier.

The systematic feeding of enemies with superior food began immediately, though its psychological impact would only be understood later. A German officer later testified to the International Red Cross, “We expected to be starved as prisoners. Instead, the Americans fed us better than our own army had. This confusion about American resources began our education.

The Liberty ships carrying PWs across the Atlantic in summer 1943, provided intensive education in American abundance. These vessels, mass-roduced at unprecedented rates, one completed every 42 hours at peak production, transported up to 30,000 prisoners monthly to the United States.

Naval records show that prisoner rations aboard these ships matched or exceeded standard crew provisions, approximately 3,500 calories daily, including fresh bread, meat, vegetables, and coffee with sugar and milk. The ship’s refrigeration systems, standard equipment on American vessels, maintained fresh food throughout the twoe crossing. Most remarkably, documented accounts confirm that ice cream was served on multiple occasions during Atlantic crossings.

The USS General MB Stewart’s log from July 1943 records serving ice cream to prisoners on July 4th using the ship’s ice cream maker that produced 10 gallons per batch. For men who hadn’t seen ice cream since before the war, this frozen dessert in the middle of the ocean defied understanding. When ships docked at ports like Norfolk and Newport News, German PSWs encountered an America that Nazi propaganda had declared impossible.

The Norfolk Naval Base, covering 4,300 acres with extensive waterfront facilities, handled more cargo daily than major German ports managed weekly. At the port exchanges, shops for dock workers, prisoners glimpsed shelves stocked with candy bars from major manufacturers like Hershey, Mars, and Nestle.

Military procurement records from 1943 show these exchanges stocked dozens of candy varieties, selling them at standard prices, 5 cents for most candy bars, the same price charged across America. The Journey inland by train provided further education. Unlike the cattle cars used for transport in Europe, German PSWs traveled in passenger coaches, the dining cars served full meals.

Documented menus from July 1943 show fried chicken, vegetables, pie, and coffee. Ps discovered this wasn’t special treatment, but standard American rail service. The prison camp system constructed across America housed PWS in conditions that exceeded Geneva Convention requirements.

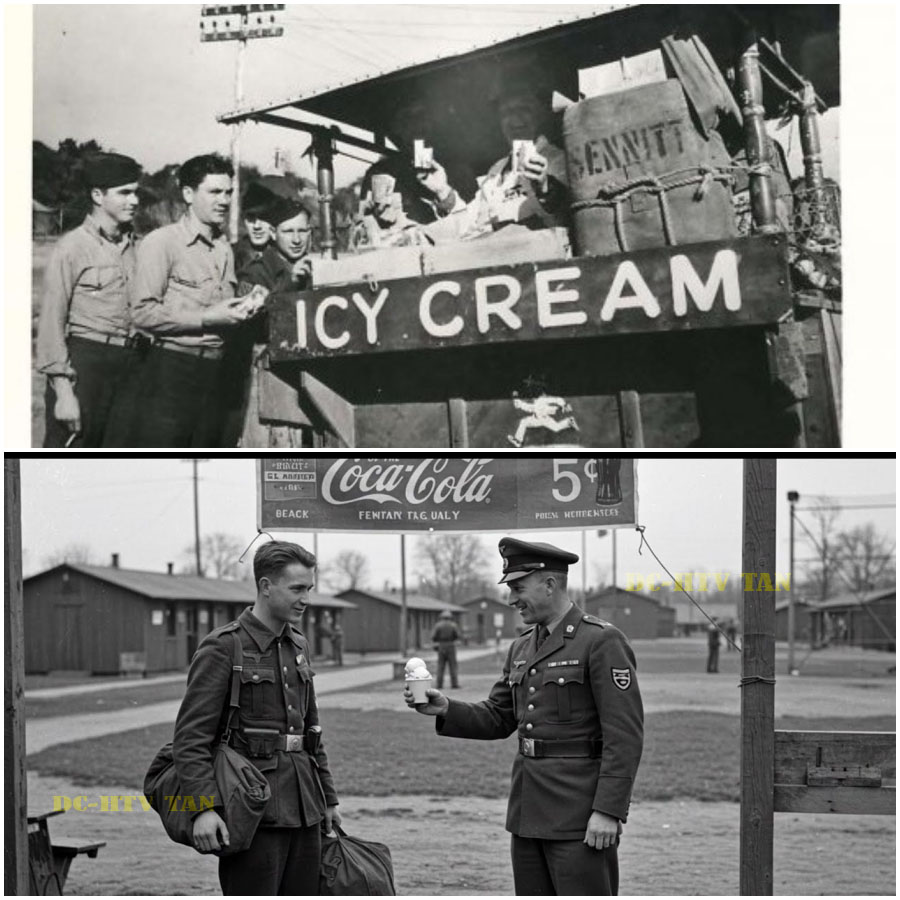

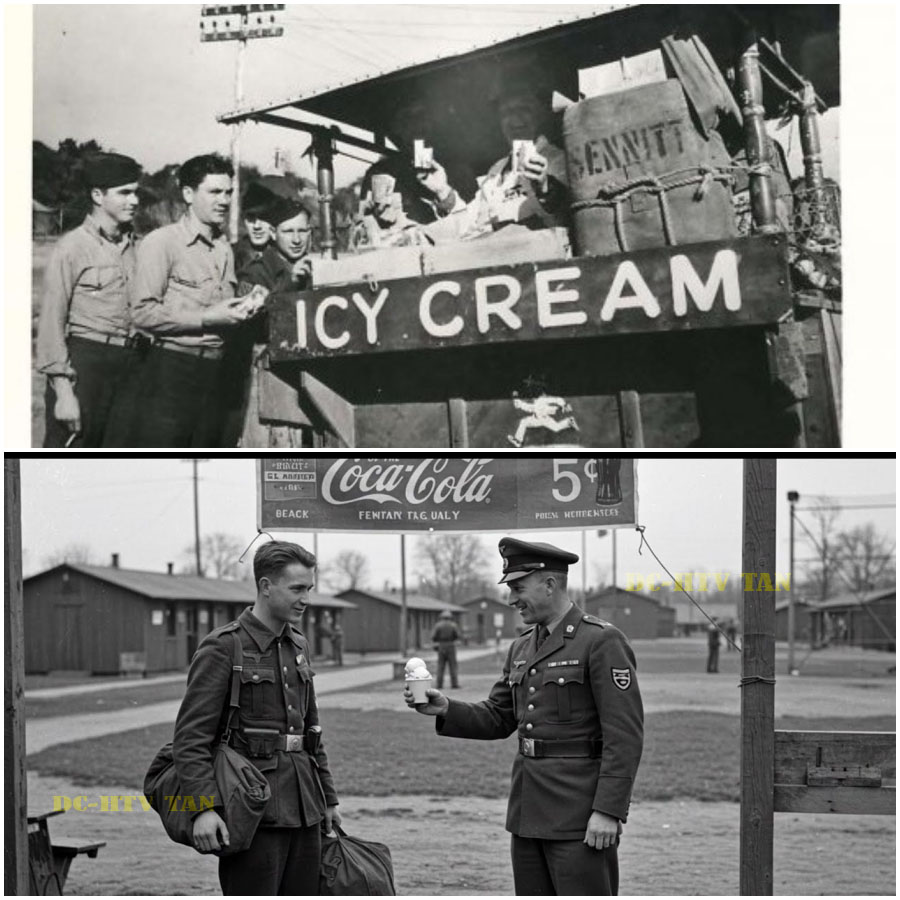

Camp Crossville, Tennessee, typical of the larger facilities, included electric lights, hot water, flush toilets, and heated barracks. But the camp exchanges, the PX stores, delivered the deepest impact. According to Army Quartermaster Records, camp exchanges stocked multiple soft drink brands, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Dr.

Pepper, RC Cola, various candy bars and confections, ice cream where refrigeration permitted, cigarettes and tobacco, fresh fruit and snacks, beer, 3.2% alcohol content. Prisoners earned 80 cents daily for labor, later raised to $1. With candy bars at 5 cents and Coca-Cola at the same price, a day’s wage could purchase 16 items abundant beyond German imagination, where such products, if available at all, required special connections.

Coca-Cola became the symbol of American industrial democracy. The Coca-Cola Company’s wartime production reached remarkable levels. Company records show 5 billion bottles produced in 1943 alone. The military contract guaranteed 5-cent Coca-Cola to American servicemen worldwide. A commitment requiring unprecedented logistics. German prisoners discovered that this soft drink, unknown to most before capture, was ubiquitous in America.

Every camp received regular deliveries. Work details observed vending machines and coolers everywhere, gas stations, factories, schools. Americans of all ages and classes drank it casually, discarding half empty bottles without thought. The standardization astounded technically minded prisoners.

Coca-Cola tasted identical whether consumed in Maine or Texas, a feat of quality control exceeding anything German industry achieved. The syrup concentrate manufactured in Atlanta and distributed nationwide to bottling plants represented industrial coordination that challenged Nazi assumptions about American chaos. Historical records from the Coca-Cola Company archives confirmed that many prison camps received weekly deliveries of 200 to 300 cases, each containing 24 bottles.

Camp Hearn, Texas alone, consumed approximately 7,000 bottles weekly during summer 1943. Ice cream in American prison camps seemed impossible to Germans who hadn’t seen it since before the war. Yet, Army records confirmed that ice cream was regularly served in camps with adequate refrigeration during summer months. The military considered ice cream essential for morale, so important that specialized ice cream ships were built for the Pacific Fleet.

At Camp Shelby, Mississippi, the July 4th, 1943 celebration included ice cream made on site. Prisoners watched as handc cranked freezers produced gallons using ice, salt, cream, sugar, and flavorings. The casual use of scarce resources, ice in July, cream, sugar for entertainment food, demonstrated priorities Germans couldn’t fathom.

By 1944, many camps had electric ice cream makers. The variety available, chocolate, vanilla, strawberry, butter pecan, exceeded what German ice cream parlors offered before the war. Prisoners could purchase ice cream bars for 10 cents, ice cream sandwiches for the same price, or cups of various flavors. Army procurement records show that larger camps ordered 50 to 100 gall of ice cream weekly during summer months.

The frequency varied by location and season, but prisoners regularly enjoyed this frozen luxury that had vanished from German life. Sugar consumption in American prison camps delivered particularly powerful impact. In Germany, sugar was strictly rationed. Civilians received 280 gram monthly when available. In American camps, sugar sat in bowls on mesh hall tables for unlimited use.

Quartermaster records from 1943 to 1945 show camps receiving 100 pound bags of refined sugar weekly. Camp bakeries used sugar liberally. Cakes, cookies, and pies appeared regularly on menus. The mess halls sweetened coffee, tea, cereals, and desserts without restriction.

One documented incident from Camp Aliceville, Alabama, illustrates the contrast. In August 1943, humid weather hardened several hundred pounds of sugar, making it difficult to use. Rather than steam and recover it, as Germans would have, kitchen staff discarded it and ordered replacement supplies. German prisoners working in the kitchen were reportedly distressed by this waste.

American chocolate consumption patterns revealed democratic abundance. Major manufacturers Hershey, Mars, Nestle produced millions of bars monthly despite wartime restrictions. The military alone purchased 380 million pounds of chocolate products during the war years. Prison camp exchanges stocked multiple chocolate varieties.

The standard Hershey bar, dations, emergency chocolate bars, and various candy bars containing chocolate were available for 5 to 10 cents. Prisoners discovered Americans had preferences among chocolate brands, casually choosing one over another. Red Cross packages distributed monthly to prisoners included chocolate bars among other items.

The American Red Cross records show that standard parcels contained chocolate or candy bars, two instant coffee, processed cheese, crackers, canned meat, cigarettes, soap. These packages supplemented regular rations, providing luxury items that exceeded what German civilians received as basic rations.

Thanksgiving 1943 introduced German prisoners to American holiday abundance. This purely American celebration demonstrated national coordination of consumption that dwarfed German organizational efforts. Army records confirm that all prison camps served traditional Thanksgiving dinner roast turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes and gravy, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, vegetables, pumpkin pie, coffee and milk.

The logistics required providing turkey dinners to 425,000 PS millions of American servicemen worldwide showcased organizational capacity. The fact that German prisoners received the same meal as American soldiers emphasized equality of treatment that contradicted Nazi racial hierarchy. Christmas 1943 brought unexpected generosity from American civilians. Church groups, civic organizations, and individuals sent packages to German PWs.

The American Friends Service Committee alone distributed 50,000 Christmas packages to enemy prisoners. These packages typically contained homemade cookies, candy, toiletries, games and books, cigarettes, writing materials. Local communities near camps often provided additional support.

In Tonkawa, Oklahoma, towns people delivered homemade treats to German prisoners at Camp Tonkawa. In Hearn, Texas, church groups brought Christmas cookies and candy to Camp Hearn. This civilian kindness toward enemies challenged Nazi ideology fundamentally. Americans who had family members fighting against Germany nevertheless showed charity to German prisoners, demonstrating strength through mercy rather than vengeance.

As labor shortages intensified, German PWs worked increasingly outside camps, witnessing American food production firsthand. By 1944, approximately 100,000 prisoners worked in agriculture and food processing, gaining intimate knowledge of American abundance. In Michigan orchards, prisoners picked cherries destined for mariskino production, those bright garnishes topping ice cream sundaes. The volume staggered them.

Single orchards producing tons of fruit for decorative purposes. At caneries, prisoners observed quality control that rejected perfectly edible food for minor imperfections. Delmonte records from 1944 show that approximately 15% of fruit was rejected for canning due to size irregularities or minor blemishes, typically diverted to animal feed.

Sugar beet processing in Colorado and Nebraska revealed agricultural mechanization beyond German achievement. Single farms produced more sugar beatets than entire German regions. Prisoners learned that American sugar production from both cane and beets reached approximately 7 million tons annually, explaining the casual abundance they witnessed.

German prisoners working near schools witnessed early versions of organized school lunch programs. Children received hot lunches including milk, protein, and vegetables. The National School Lunch Act would formalize this in 1946, but precedent programs operated during the war. The milk program particularly impressed German observers.

Many schools provided fresh milk to children daily. The logistics of daily delivery to thousands of schools demonstrated organizational capacity that Germany couldn’t achieve for military supplies. Some school cafeterias offered ice cream for additional purchase.

The concept of children buying frozen desserts at school while German children faced food shortages created profound impact among prisoner observers. When minimum security prisoners ate at American diners under guard, they encountered democratic abundance. These small restaurants offered menus that would have graced elite German establishments available to anyone with modest funds. Documented prices from 1944 show hamburger 25, Coca-Cola 5, pie slice 15 cents, ice cream sundae 25, full dinner special 65 to75.

The equality of service, anyone could order anything, contradicted German social stratification. A factory worker and bank president ate identical meals at adjacent counter stools served by the same waitress for the same price. As prisoners gained access to American publications, they discovered production statistics that dwarfed German efforts.

1944 American production documented figures. Sugar approximately 7 million tons. Chocolate and cocoa products 380 million pounds military alone. Coca-Cola 5 billion bottles 1943 figure. Ice cream over 500 million gallons. Milk 119 billion. German production same period. Sugar heavily rationed primarily from beets. Chocolate military priority only. soft drinks, minimal production.

Ice cream virtually non-existent. Milk severely rationed. These numbers published openly in American media demonstrated that America’s wartime production exceeded Germany’s peaceime peaks. By late 1944, German PWs were sending food packages to Germany rather than receiving them.

Using camp wages, prisoners purchased American products to mail home, chocolate bars, instant coffee, canned goods. International Red Cross records confirm this reversal. German prisoners in America sent approximately 11 million parcels to Germany during their captivity, most containing food items. The impact on German families receiving American abundance from imprisoned relatives while they faced starvation in freedom profoundly undermined Nazi ideology.

American rationing implemented during the war revealed the gulf between societies. Americans complained about sugar rationing of two monthly per person, more than triple the German allowance when available. American meat rationing at 28 ounces weekly per person exceeded what Germans received monthly. Even rationed, Americans maintained consumption levels. Germans considered impossible luxury.

The Office of Price Administration records show Americans purchased 74 of sugar per capita in 1944 despite rationing, 10 times German consumption. Beyond Coca-Cola, prisoners discovered America’s soft drink industry. Pepsi Cola, Dr. Pepper, RC Cola, Orange Crush, and regional brands competed nationwide.

The variety itself, multiple companies producing similar products, demonstrated market abundance impossible under German controlled economy. Bottling plants operated in every major city. The technology, carbonation, bottling, capping, labeling was standardized and efficient. Single plants produced millions of bottles annually. The distribution network reached every small town, gas station, and grocery store.

American soft drink production reached billions of bottles annually by war’s end, dozens of bottles per American citizen yearly. This single industry’s output exceeded entire sectors of German consumer production. Spring 1945 brought the final blow. As American forces advanced through Germany, German PS in America watched news reels of GIs distributing chocolate and gum to German children.

These children’s joy at receiving American candy their own government couldn’t provide completed the ideological demolition. The contrast was stark. American soldiers advancing through enemy territory carried enough candy to give away, while the German state that promised triumph delivered starvation. Films of concentration camp liberations showed American troops sharing rations with skeletal survivors, demonstrating humanity toward victims of the regime German soldiers had served.

Between 1945 and 1946, German PSWs returned to a destroyed homeland. Many prisoners had gained significant weight in American captivity, while their families lost weight to starvation in German freedom. They brought knowledge of abundance to a land of absolute scarcity. Medical examinations showed German PS generally returned healthier than when captured.

They returned to families weakened by deprivation. This physical evidence of American plenty versus German deprivation was undeniable. Many prisoners brought final Red Cross packages home. Chocolate, coffee, and canned goods that became family treasures. Children who had forgotten chocolate’s taste received Hershey bars from fathers who had eaten ice cream regularly in prison camps.

Former PWs became unexpected advocates for the Marshall Plan. They had witnessed American abundance that wasn’t zero sum, prosperity through production rather than conquest. Their testimony that Americans could afford to rebuild enemies influenced German acceptance of American aid. These men understood that American power came from productive capacity, not extraction. They had seen a society wealthy enough to waste food while fighting a global war.

This mental model, creation rather than conquest, shaped West Germany’s economic approach. The German economic miracle of the 1950s was partially built on knowledge gained in American prison camps. Former PWs who had witnessed American production methods, distribution systems, and consumer abundance applied these lessons to German reconstruction. They had learned that mass production could make luxuries affordable.

Standardization enabled quality and efficiency. Consumer abundance created political stability. Industrial democracy could outproduce authoritarian control. These lessons learned through Coca-Cola and ice cream shaped a generation of German business and political leaders.

The transformation of German PWS through American food abundance is documented in military quartermaster records, international Red Cross reports, corporate production records, particularly Coca-Cola archives, PW correspondents, censored but preserved, post-war interviews and memoirs, academic studies, particularly Arnold Kramer’s extensive research.

Arnold Kramer, the leading historian of German PSWs in America, concluded that food abundance was central to ideological transformation. His research confirmed that casual American plenty accomplished what formal re-education programs couldn’t complete demolition of Nazi superiority myths.

The statistical summary, the numbers tell an irrefutable story. Average P consumption 1943 to 1946. Daily calories 3,300 to 3,600. Sugar 4 monthly available. Meat 32 oz weekly. Milk 1 quart daily available. Ice cream served regularly during summer. Soft drinks unlimited at 5 cents each. German civilian rations, same period. Daily calories, 1,200 to 1,500.

Sugar, 280 g monthly when available. Meat 10.5 o weekly, often unavailable. Milk severely rationed. Ice cream non-existent. Soft drinks none available. These disparities weren’t propaganda, but documented reality. Enemy prisoners ate better than German civilians, proving American abundance extended even to defeated foes.

The P experience with American food culture influenced postwar Germany profoundly. Coca-Cola returned to West Germany in 1949, becoming a symbol of American alliance. Ice cream parlors modeling American soda fountains appeared in German cities. Candy bars and chewing gum became symbols of recovery.

Former prisoners of war often became importers of American food products, understanding their appeal from personal experience. They knew these products represented more than taste. They symbolized abundance, democracy, and modernity. The introduction of supermarkets to Germany in the 1950s was championed by former PWs who had witnessed American grocery stores. They understood that democratic abundance required new distribution methods, not just production increases.

In various post-war interviews and memoirs, German PSWs consistently identified food abundance as transformative. A former Africa Corps officer stated in a 1975 interview, “We expected to defeat a weak, divided America. Instead, we found a nation that could give ice cream to enemies. That’s when we knew we had lost more than a war.

We had lost our entire world view. Another veteran interviewed for a documentary in 1985 recalled, “My first Coca-Cola was like drinking the future. It was sweet, fizzing, completely unnecessary, and available to anyone for a nickel. That drink contained everything Nazi Germany wasn’t. Abundant, democratic, joyful.” These testimonies collected across decades confirm that American food abundance achieved what military defeat alone couldn’t, complete ideological transformation.

The men who arrived as Nazi warriors left as witnesses to democratic prosperity. Historians recognize the German P experience in America as remarkably successful re-education through abundance rather than propaganda. The program succeeded because it relied on observation rather than instruction. PS saw American society functioning at peak productivity while treating enemies with dignity. The food aspect was crucial because it was universal.

Everyone understands hunger and satisfaction. Undeniable. Weight gain and health improvement were visible. Continuous three meals daily plus canteen purchases. comparative prisoners knew German deprivation intimately. Every meal became a lesson in American industrial capacity.

Every Coca-Cola demonstrated standardization and distribution. Every ice cream Sunday showed that abundance could be democratic. Children of prisoners of war grew up hearing about American abundance in prison camps. These stories, initially seeming fantastic, were validated as West Germany recovered and American products became available.

The mythology of American plenty, born in prison camps, shaped generations of German American relations. Many P children later studied or worked in America. Drawn by their father’s stories of impossible abundance, they found the reality matched the tales. Supermarkets stocked with variety.

Soda fountains serving Sundays, candy aisles offering dozens of choices. This multigenerational impact extended beyond individuals. West German business culture absorbed lessons about consumer abundance, quality standardization, and democratic markets. The economic miracle wasn’t just about production, but about creating abundance for ordinary citizens.

Today, McDonald’s operates over 1,400 restaurants in Germany. Coca-Cola is ubiquitous. Ice cream is ordinary. The transformation from scarcity to abundance, initiated in American prison camps, is complete. Yet, the historical lesson remains powerful. Ideological transformation through abundance rather than deprivation.

Kindness rather than cruelty, demonstration rather than propaganda. The German PS who couldn’t believe ice cream and Coca-Cola in American prison camps witnessed democracy’s ultimate weapon. The ability to create such abundance that it could be casually shared with enemies. The story of German PS and American food abundance represents history’s most unusual victory.

A war won through generosity, an ideology defeated by ice cream, a world view shattered by soft drinks. These men experienced transformation not through punishment but through plenty. They arrived believing in German superiority and American weakness. They left understanding that American strength came from productive capacity so vast it could waste resources without concern.

The society that could give Coca-Cola to prisoners for 5 cents possessed power beyond military might. The ice cream sundae with its layers of excess ice cream, syrup, whipped cream, nuts, cherry, became a metaphor for American abundance. Each component alone exceeded German dreams.

Combined, they represented impossible luxury made routine. That enemies could order seconds, while German children faced hunger revealed the totality of Nazi failure. Former PS often recalled specific moments of revelation. The first Coca-Cola’s fizz, the first spoonful of ice cream, the first bite of a Hershey bar. These sensory memories carried more power than any argument. They had tasted democracy, and it was sweet.

The transformation was complete and irrevocable. Men who had marched for the Third Reich returned as apostles of abundance, carrying the revolutionary message that prosperity came from freedom, not conquest. They had learned that America’s secret weapon wasn’t military might, but the ability to give ice cream to enemies. In the end, the bottles of Coca-Cola and dishes of ice cream served in American prison camps achieved what armies could only attempt, the complete transformation of enemy hearts and minds.

The German PS who couldn’t believe such abundance existed became its greatest witnesses. Carrying home the truth that democracy tasted like chocolate and freedom fizzed like carbonation. Their story reminds us that sometimes the greatest victories are won not through destruction but through demonstration, not through taking, but through giving, not through hatred, but through the simple act of serving ice cream to enemies on a hot summer day.

The men who experienced American abundance as prisoners became freedom’s most unlikely ambassadors, transformed forever by the impossible reality of Coca-Cola and ice cream in American prison camps. Please.