Japanese POWs Couldn’t Believe Hamburgers and Coca-Cola in American POW Camps….

The metal cup trembled in Hiroshi Tanaka’s weathered hands as he took his first sip of ice cold Coca-Cola. The sweet, fizzy liquid hit his parched throat like liquid lightning. Around him, fellow Japanese prisoners of war stared in bewilderment at the American guards distributing hamburgers wrapped in paper.

French fries served in cardboard containers and bottles of soda pop that sparkled like liquid amber in the harsh Nevada sun. It was August 1945, and for these men who had spent years believing they would die fighting for the emperor, this moment represented something far more shocking than military defeat.

They were witnessing their first encounter with American abundance, a glimpse into a world so alien, it might as well have been another planet. Tanaka, a former sergeant in the Imperial Japanese Navy, had expected death or torture when he was captured during the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

What he hadn’t expected was to find himself sitting at a picnic table in Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, watching American soldiers casually toss halfeaten sandwiches into trash bins while he and his fellow prisoners received better meals than many Japanese civilians had seen in years. The cultural shock was so profound that some prisoners initially refused to eat, convinced the abundant food was either poisoned or part of some elaborate psychological warfare. But this story isn’t just about hamburgers and Coca-Cola.

It’s about a collision between two worlds. One driven by scarcity, honor, and sacrifice. The other by abundance, efficiency, and mass production. When Japanese prisoners of war encountered American prison camps during World War II, they weren’t just experiencing captivity. They were getting their first taste of a consumer culture that would eventually reshape their homeland and the entire world.

The year was 1942, and the Pacific War was consuming both nations in a spiral of violence that would ultimately claim millions of lives. For Japan, this was a fight for survival against Western imperialism, a sacred war where death was preferable to surrender. The Bushidto code, deeply embedded in Japanese military culture, taught soldiers that capture meant dishonor, not just for themselves, but for their families and ancestors. This wasn’t mere propaganda.

It was a belief system so powerful that Japanese soldiers would literally choose death over captivity, often taking their own lives rather than face the shame of surrender. Meanwhile, across the Pacific, America was mobilizing its industrial might on a scale never before seen in human history. Factories that once produced automobiles now churned out tanks and aircraft.

Assembly lines that had revolutionized consumer goods were retoled for instruments of war. But perhaps most remarkably, the American military was also revolutionizing how it fed its troops and its prisoners. The contrast couldn’t have been starker.

Japanese soldiers carried rice balls and dried fish when they were lucky enough to have rations at all. Many subsisted on whatever they could forage from jungle environments or captured from enemy supplies. Their equipment was often improvised. Their supply lines stretched impossibly thin across thousands of miles of ocean. They fought with the ferocity of men who believed their very souls depended on victory.

But they fought hungry, sick, and increasingly desperate. As the war dragged on, American forces, by contrast, were backed by an industrial machine that could produce not just weapons and vehicles, but an endless stream of processed foods, bottled beverages, and manufactured goods. The same country that had invented the assembly line and mass production was now applying those innovations to warfare on a global scale. When American soldiers went into battle, they carried Krations that included chocolate bars,

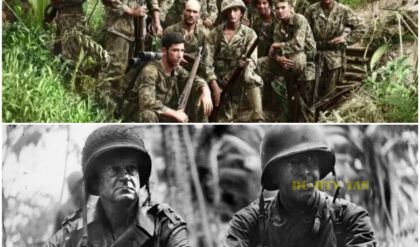

cigarettes, and instant coffee. When they established prison camps, they brought with them the entire apparatus of American consumer culture, including the fast food and soft drinks that would soon astonish their Japanese captives. The first major wave of Japanese prisoners began arriving in American custody following the Guadal Canal campaign in late 1942 and early 1943.

These were not the broken, demoralized soldiers that American commanders might have expected. Many were elite troops, marines, paratroopers, and naval aviators who had been at the forefront of Japan’s early victories across the Pacific. They had conquered Singapore, Hong Kong, and the Dutch East Indies. They had bombed Pearl Harbor and dominated the seas from the Philippines to the Solomon Islands.

Now, suddenly, they found themselves prisoners in a land that seemed to operate by completely different rules. The shock began the moment they were processed into American custody. Sergeant Yukio Matsumoto, captured during the fighting on Saipan, later described his amazement at the medical treatment he received.

The American doctors cleaned my wounds with supplies I had never seen, he recalled in postwar interviews. They had bandages that came in sealed packages, medicines in glass bottles with printed labels, and instruments that gleamed like silver. In Japan, even our military hospitals were running short of basic supplies. Here, they seemed to have an endless amount of everything.

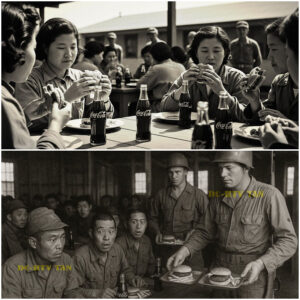

But it was the food that truly boggled their minds. American military doctrine during World War II emphasized keeping prisoners healthy and well-fed. Partly for practical reasons. Sick prisoners required more resources, but also as part of a broader strategy to demonstrate American superiority.

The Geneva Conventions provided a baseline for prisoner treatment, but American camps often exceeded those requirements by substantial margins. The first meal many Japanese prisoners received in American custody was often their introduction to mass-roduced American food. Canned meat, processed cheese, white bread that seemed impossibly soft and sweet compared to the coarse grain products they knew from home.

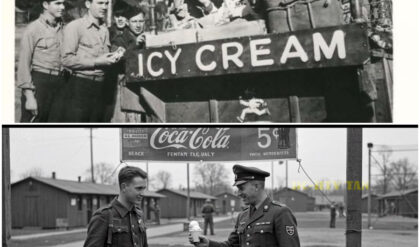

But perhaps nothing symbolized the cultural divide more than Coca-Cola. By 1943, Coca-Cola had become so integral to American military culture that the company had established bottling plants near major bases and even in war zones. The sweet carbonated drink was seen as a taste of home for homesick gis. But for Japanese prisoners encountering it for the first time, it represented something almost incomprehensible.

A beverage that served no nutritional purpose, provided no sustenance, yet was consumed purely for pleasure, and widely available even in wartime. Lieutenant Commander Saburro Hayashi, shot down over the Marshall Islands, described his first encounter with American prison camp life in vivid detail.

They brought us to a place that looked like a small city. There were buildings laid out in perfect rows with electricity, running water, and paved roads. The American guards moved with a casualness that shocked us. They chewed gum, smoked cigarettes freely, and seemed completely unconcerned about conserving resources.

When they offered us lunch, I thought it was some kind of test. The lunch in question was hamburgers, French fries, and Coca-Cola, a meal that would become legendary among Japanese prisoner communities. The hamburger, an assembly line creation of ground beef, processed cheese, and mass-produced buns, represented the pinnacle of American industrial food production.

The French fries, cut to uniform sizes and deep fried in abundant cooking oil, showcased a level of resource availability that seemed almost magical to men who had been fighting a war of extreme scarcity. And the Coca-Cola with its complex formula and global distribution network embodied the reach and sophistication of American consumer capitalism.

Many prisoners initially refused to eat these strange new foods. Some suspected poison. Others worried that accepting American hospitality would somehow dishonor their oath to the emperor. But hunger has a way of overcoming ideology. And gradually, cautiously, the prisoners began to sample what their capttors offered.

The taste experiences were revoly. Japanese cuisine, refined over centuries, emphasized subtle flavors, seasonal ingredients, and careful preparation. American fast food, by contrast, was designed for mass appeal, bold flavors, and efficient consumption. The hamburgers were salty, greasy, and satisfying in ways that rice and fish could never be.

The French fries delivered concentrated calories and satisfaction. The Coca-Cola provided an intense sugar rush that many prisoners found almost addictive. But beyond the sensory experience was something even more profound, the realization of what these foods represented. Here was a nation that could afford to feed its prisoners better than many Japanese civilians were eating.

Here was a military that had so much surplus production capacity that it could manufacture soft drinks and distribute them freely. Here was an enemy that seemed to possess resources on a scale that made Japan’s entire war effort look like a desperate gamble.

Private First Class Kenji Nakamura, captured during the fighting on Ewima, put it most succinctly. We had been told that Americans were soft, that they were weak because they loved comfort more than honor. But when I saw how much they could produce, how easily they could create abundance, even in prison camps thousands of miles from home, I began to understand that we had been fighting a war we could never win.

The prison camps themselves reinforced this message at every turn. Camp Shelby in Mississippi, Camp McCoy in Wisconsin, Camp Livingston in Louisiana. These facilities were constructed with the same industrial efficiency that characterized everything else in wartime America. barracks built to standard designs, mess halls capable of feeding thousands, recreational facilities that included libraries, sports fields, and even movie theaters. The contrast with Japanese facilities were stark.

Japan’s own prisoner of war camps were notoriously harsh, partly due to cultural attitudes towards surrender, but also because Japan simply lacked the resources to maintain large-scale detention facilities. Japanese military doctrine had never anticipated having to house and feed large numbers of enemy prisoners, and the country’s strained supply lines couldn’t support such operations, even if the will had been there. American camps, by contrast, operated like small cities.

They had their own power plants, water treatment facilities, and supply networks. Trucks arrived daily with fresh food, medical supplies, and consumer goods. The waste generated by these facilities, food scraps, packaging materials, worn out clothing, often exceeded what entire Japanese military units had available for their own use.

For Japanese prisoners, watching this daily display of abundance was both fascinating and demoralizing. Many began to keep detailed mental notes of what they observed, not just out of curiosity, but as intelligence that might someday prove valuable. What they discovered was a nation that had essentially industrialized warfare, applying the same mass production techniques that had revolutionized consumer goods to every aspect of military operations.

The food service alone was a marvel of logistics. Meals were planned weeks in advance. Ingredients sourced from suppliers across the continent. Preparation standardized to ensure consistency across different facilities.

The kitchen equipment, industrial stoves, mechanical mixers, refrigeration units, represented technology that most Japanese had never seen outside of major urban centers. Even the serving utensils were mass-produced to consistent specifications, a far cry from the improvised equipment that characterized much of Japan’s military infrastructure. But perhaps most shocking of all was the casual waste.

American guards would discard halfeaten sandwiches, pour out unwanted coffee, throw away damaged packaging without a second thought. For prisoners from a society where every grain of rice was precious, where families saved and reused everything from string to metal scraps, this apparent disregard for resources was almost incomprehensible.

Some prisoners tried to collect and save items that Americans casually discarded. Guards would often look the other way as Japanese PS carefully folded used paper napkins, saved empty bottles, or collected scraps of wood and metal. What the guards saw as harmless collecting, the prisoners saw as gathering precious resources that might have value in a post-war world where scarcity would surely return.

The cultural exchange worked both ways. American guards, many of them young men from small towns and rural areas, were often equally fascinated by their Japanese captives. Here were representatives of a mysterious enemy culture. Men who had fought with legendary ferocity, but who now seemed almost childlike in their wonder at American abundance.

Some guards began to see their prisoners not as faceless enemies, but as individuals with their own stories, fears, and dreams. Corporal James Mitchell from Iowa, who worked as a guard at Camp McCoy, later wrote about his experiences. At first, we thought they were all fanatics who would try to kill us the first chance they got.

But watching them react to simple things like ice cream or a candy bar, you realize they were just soldiers like us. Except they’d been fighting a war with almost nothing while we had everything we could want and more. These personal connections formed over shared meals and simple human interactions would prove crucial in the months and years to come.

As the war ground toward its inevitable conclusion, many Japanese prisoners began to realize that their pre-war assumptions about American society had been not just wrong, but dangerously naive. The fast food and Coca-Cola were just the most visible symbols of a deeper truth. that America possessed not just superior military technology, but superior productive capacity on every level.

The same factories that could churn out thousands of identical hamburgers could also produce tanks, aircraft, and ships at rates that Japan could never match. The same distribution networks that delivered soft drinks to remote prison camps could also supply ammunition, fuel, and equipment to armies fighting on multiple continents simultaneously.

As 1944 turned into 1945 and reports of American bombing raids on Japanese cities began to filter into the prison camps, many Japanese prisoners began to grapple with an uncomfortable realization. They had been fighting a war against an enemy whose resource base was so vast that they could afford to treat prisoners better than Japan could treat its own soldiers.

The implications were staggering, and they would only become more apparent as the war rushed toward its dramatic conclusion. The stage was set for revelations that would shake these prisoners to their core, challenging everything they had believed about their homeland, their enemy, and the nature of modern warfare itself.

But that transformation was still to come, hidden in the months ahead like a secret ingredient in a Coca-Cola formula, waiting to change everything these men thought they knew about the world. By the spring of 1945, the impossible had become routine in American prison camps across the continental United States.

Japanese prisoners who had once viewed a single grain of rice as precious now watched American guards casually open fresh cans of Coca-Cola, take a few sips, and abandon them half-finish. Men who had been taught that death was preferable to surrender were learning to operate ice cream machines in camp mess halls. The transformation wasn’t just dietry.

It was philosophical, challenging the very foundations of everything these prisoners had believed about strength, honor, and what it meant to be a powerful nation. Captain Ichiro Sato, formerly of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 32nd Infantry Regiment, had spent 3 months at Camp Livingston in Louisiana, when he experienced what he would later describe as his moment of complete awakening.

It was a sweltering afternoon in May 1945, and the camp’s American commander had arranged for a special treat. A Coca-Cola truck would visit the prison compound, and each prisoner would receive a ice cold bottle of the famous soft drink. Sarto watched in fascination as the red truck pulled up to the camp gate.

The driver, a cheerful man in his 50s with a company uniform, began unloading cases of bottles with practice efficiency. Each bottle was identical, each cap perfectly crimped, each label printed with the same flowing script that Sato had now learned to recognize as the Coca-Cola trademark. But what struck him most profoundly wasn’t the uniformity of the product.

It was the casual abundance of the entire operation. This truck, Sato later wrote in his memoirs, served not just our camp, but a dozen other facilities across Louisiana. The driver told us through an interpreter that his company produced millions of these bottles every day, not just for the military, but for ordinary civilians who could buy them at any corner store. I tried to imagine millions of bottles being produced daily, and I could not.

In Japan, we treasured a single orange. Here, they were manufacturing liquid refreshment on an industrial scale that boggled the mind. The Coca-Cola distribution system that seemed so routine to Americans represented something revolutionary to Japanese prisoners.

Here was a single company that had managed to establish production and distribution networks spanning an entire continent and beyond. Coca-Cola plants were operating in war zones on remote islands wherever American forces were stationed. The same logistical capability that could deliver soft drinks to the middle of Louisiana could deliver ammunition to the front lines in the Pacific, fuel to aircraft carriers, and medical supplies to field hospitals.

But it wasn’t just the scale that impressed the prisoners. It was the apparent effortlessness of it all. American abundance seemed to flow as naturally as water from a tap. Food appeared in mesh halls three times a day without fail. Clean clothing was distributed weekly. Medical supplies never seemed to run short.

Entertainment, movies, books, sports equipment arrived regularly, as if someone somewhere was carefully monitoring the morale of enemy prisoners and ensuring they had access to diversions that most Japanese civilians could only dream of. Lieutenant Masau Fujiwara, a naval aviator who had been shot down over Guadal Canal, found himself assigned to work in the camp’s kitchen as part of the prisoner labor program. What he discovered there challenged everything he thought he knew about food production and military

logistics. The kitchen received daily deliveries of meat, vegetables, dairy products, and processed foods in quantities that would have fed his entire squadron for weeks. Industrial-sized cans of vegetables, massive blocks of cheese, sides of beef that required multiple men to carry. The sheer volume of food flowing through a single prison camp was staggering.

I had been taught that Americans were weak because they were soft because they preferred comfort to sacrifice. Fujiwara later reflected. But working in that kitchen, I began to understand that their softness was actually a kind of strength we had never imagined. They had built a society so productive, so efficient that they could afford to be generous even to their enemies. This wasn’t weakness. It was power of a completely different kind.

The kitchen work also gave Fujiwara insights into American food culture that went far beyond simple abundance. He learned that many of the foods he was helping to prepare, hamburgers, hot dogs, French fries, were relatively recent innovations, products of industrialization and mass production rather than ancient culinary traditions.

The hamburger he discovered had been invented as a quick, efficient way to serve meat to factory workers. French fries were a standardized product that could be prepared identically in restaurants across the country. Even Coca-Cola, with its closely guarded secret formula, was ultimately a triumph of industrial chemistry and mass marketing. These foods weren’t just nutrition.

They were symbols of a society that had learned to standardize pleasure, to mass-produce satisfaction, to turn even eating into an efficient, optimized experience. The contrast with Japanese cuisine with its emphasis on seasonal ingredients, careful preparation, and aesthetic presentation couldn’t have been more stark.

Both approaches had their merits, but only one could feed millions of soldiers fighting a global war. As 1945 progressed and news of the war’s progress filtered into the camps, many Japanese prisoners began to experience a profound psychological transformation. The abundance they witnessed daily in American prison camps forced them to reconsider everything they had been told about their enemy and about the nature of their own country’s war effort.

Sergeant Hiroshi Yamamoto, captured during the fighting on Saipan, put it bluntly in letters he wrote after the war. We had been told that America was a nation of weaklings who would collapse at the first sign of real hardship. But here I was, a prisoner of war, eating better than I had eaten in years of military service in Japan.

If this was how they treated their enemies, how well did they treat their own people? And if they could afford such generosity in wartime, what did that say about the true balance of power in this conflict? The question haunted many prisoners as the summer of 1945 wore on. Reports from the Pacific Theater were becoming increasingly grim for Japan.

American bombers were ranging freely over Japanese cities, and the prison camp guards spoke openly of inevitable victory. Some prisoners clung to hope that Japan’s legendary fighting spirit would somehow prevail. But the evidence of American industrial might was all around them, as visible as the Coca-Cola bottles that accumulated in waste bins and the hamburger wrappers that littered picnic tables.

The end, when it came, was swift and shocking. On August 15th, 1945, Emperor Hirohito’s surrender broadcast reached the prison camps through Japanese language radio programs. For many prisoners, the news was devastating, not just because their country had lost, but because the reality of defeat forced them to confront how completely they had misunderstood the nature of the conflict they had been fighting.

In the days following Japan’s surrender, something remarkable happened in American prison camps. The psychological barriers between captives and captives began to break down in ways that would have seemed impossible just weeks earlier. American guards, many of whom had lost friends and family members in the Pacific War, found themselves sharing meals and conversations with former enemies who now seemed less like dangerous fanatics and more like fellow humans trying to make sense of a changed world. The fast food and soft drinks that had once symbolized an alien

culture now became bridges to understanding. Japanese prisoners who had initially been suspicious of hamburgers and Coca-Cola now found comfort in these familiar camp foods. Some guards began teaching prisoners how to prepare American dishes, while prisoners shared techniques for preparing rice and vegetables in ways that American cooks had never imagined.

Private Kenji Suzuki, who had spent over a year at Camp McCoy, described the post-surrender period as a time of profound learning. Before the surrender, I ate American food because I was hungry and had no choice. After the surrender, I began to understand what this food represented. It wasn’t just about feeding people efficiently. It was about creating a shared experience, a common culture that could unite people from different backgrounds.

When I watched American soldiers from different states, different ethnic backgrounds, all enjoying the same hamburgers and Coca-Cola, I began to understand something important about how American society worked. This insight would prove prophetic.

In the months following Japan’s surrender, as prisoners began to be processed for repatriation, many found themselves reluctant to return to a homeland they now realized they barely understood. The Japan they had left was a society built on scarcity, hierarchy, and sacrifice. The America they had discovered was built on abundance, efficiency, and mass consumption. The contrast raised uncomfortable questions about which model would prove more successful in the postwar world.

The repatriation process itself provided one final lesson in American organizational efficiency. Prisoners were processed through massive staging areas where they received new clothing, medical examinations, and documentation. The logistics were staggering.

Thousands of former prisoners of war, each requiring individual attention, processed through a system that moved with clockwork precision. And throughout it all, the familiar comforts of American mass culture were present. Hot meals served on standardized trays. Cold soft drinks available at every stop. Entertainment and diversion provided as routinely as medical care. Many prisoners received care packages for their journey home containing items that would have been luxury goods in wartime Japan.

Chocolate bars, cigarettes, canned foods, and yes, bottles of Coca-Cola for the long ship voyage back to their devastated homeland. The generosity was both touching and strategic, a final demonstration of American abundance that would send these former enemies home with a very different understanding of the nation they had fought.

The ships that carried Japanese prisoners back to their homeland in late 1945 and early 1946 were themselves symbols of American industrial might. Many were Liberty ships, mass-produced cargo vessels that had been churned out by American shipyards at the rate of one every few days during the war’s peak. These vessels, loaded with repatriated prisoners and relief supplies, represented the same productive capacity that had made hamburgers and Coca-Cola available in remote prison camps throughout the war.

As these ships approached the Japanese coastline, many former prisoners got their first glimpse of what American bombers had done to their homeland. Cities lay in ruins, harbors were clogged with sunken ships, and the industrial infrastructure that had once seemed so impressive to Japanese eyes was now revealed as primitive compared to what they had witnessed in America.

The contrast was heartbreaking and illuminating in equal measure. Hiroshi Tanaka, the former naval sergeant whose story opened our narrative, stood at the rail of a repatriation ship as it entered Tokyo Bay in December 1945. In his baggage was a nearly empty bottle of Coca-Cola that he had been saving for this moment. As he looked out at the devastated landscape of his homeland, he took a final sip of the sweet, fizzy drink that had come to symbolize everything he had learned about American power and abundance. I realized, he later wrote, that we had been fighting

not just a war, but an entire way of thinking about what a modern society could become. We had approached the conflict as if it were still the 19th century, as if willpower and sacrifice could overcome industrial capacity and technological innovation. The Americans had approached it as an engineering problem to be solved through mass production and efficient distribution.

Looking at the ruins of Tokyo, it was clear which approach had proven more effective. But the story doesn’t end with defeat and devastation. In the years that followed, many former prisoners of war became bridges between the two cultures, helping to rebuild Japan according to principles they had first encountered in American prison camps.

The abundance they had witnessed, the efficiency they had observed, the casual prosperity that had once seemed so alien. All of these became models for Japan’s remarkable post-war reconstruction. The fast food and soft drinks that had once shocked Japanese prisoners were among the first American cultural exports to gain acceptance in occupied Japan.

By the 1950s, Coca-Cola was being bottled in Japan itself, and Americanstyle restaurants were becoming popular in major cities. The former enemies had become students, eager to learn the secrets of abundance and efficiency they had first encountered as prisoners of war.

Some of the very men who had once stared in amazement at hamburgers and French fries became entrepreneurs in the new Japan, establishing businesses based on principles of mass production and standardization they had observed in American prison camps. Others became educators, teaching a new generation of Japanese about the importance of industrial efficiency and consumer satisfaction.

A few even became diplomats, helping to forge the alliance that would transform former enemies into close partners. The transformation wasn’t just economic, it was cultural and psychological. The Japan that emerged from occupation was a nation that had learned to embrace abundance rather than scarcity, efficiency rather than sacrifice, prosperity rather than mere survival.

The young Japanese who grew up in this new society would find hamburgers and Coca-Cola as familiar as rice and tea, symbols not of foreign occupation, but of modern prosperity. Today, Japan is one of the world’s most prosperous nations, a leader in technology and manufacturing, a society that has mastered the art of mass production and efficient distribution. Visitors to Tokyo or Asaka can find McDonald’s restaurants serving hamburgers and Coca-Cola on virtually every street corner, indistinguishable from their American counterparts.

The foods that once represented an alien culture have become as Japanese as sushi and sake. But perhaps the most profound legacy of those prison camp encounters lies not in the spread of fast food, but in the transformation of thinking about what a society can achieve when it prioritizes abundance over scarcity, efficiency over tradition, and pragmatic solutions over ideological purity.

The Japanese prisoners who marveled at American abundance in 1945 lived to see their own country become a model of prosperity and efficiency that other nations would study and emulate. The metal cup may no longer tremble. The hamburgers may no longer seem strange and the Coca-Cola may have lost its power to shock. But the lesson remains as relevant today as it was in those sweltering prison camps of 1945.

That true strength in the modern world comes not from the willingness to sacrifice but from the capacity to create, to produce, to build abundance where once there was scarcity. In the end, the Japanese prisoners who couldn’t believe fast food and Coca-Cola in American prison camps discovered something more valuable than any military intelligence or strategic secret.

They discovered the power of a different way of thinking about human potential. one that would ultimately help transform not just Japan, but the entire modern world. The fizzy drink and the paper wrapped hamburger had carried within them the seeds of a revolution that would reshape the global economy and redefine what it meant to live in prosperity and peace.

The war was over, but the real victory, the triumph of abundance over scarcity, of efficiency over waste, of hope over despair, was just beginning.