Japanese Soldiers Couldn’t Believe The Firepower Americans Unleashed With Their Heavy Machine Guns….

December 1942, Guadal Canal. Late afternoon. Private Kenji Watanabi of the Imperial Japanese Army crawled through jungle undergrowth, sweat pouring down his back, rifle clutched tight. His squad had been ordered to silence an American position holding the ridge above the Mataniko River.

They expected a brief firefight, perhaps a few rifles, maybe a light machine gun. What they encountered instead froze them in disbelief. From the ridgeeline came a steady, thunderous roar. Not bursts, but streams of fire so thick they seemed to stitch the jungle itself together. Branches snapped, earth erupted, and men fell screaming before they ever saw the enemy.

Watanabe flattened himself against the ground, eyes wide. How can they fire so long without stopping? He thought. It was his first encounter with the weapon that would come to symbolize American firepower in the Pacific. The heavy machine gun. For Japanese soldiers, the shock lay not only in the weapon’s lethality, but in its relentlessness.

The US Army and Marines fielded the Browning M1917 water cooled and the M250 caliber heavy machine gun. Both descendants of John Browning’s genius designs. These weapons combined high rates of fire with near indestructible reliability. In battles across Guadal Canal, Tarawa, Saipan, Ioima, and Okinawa, Japanese attackers who had trained to charge bravely through rifle fire were cut down in waves by guns that never seemed to tire.

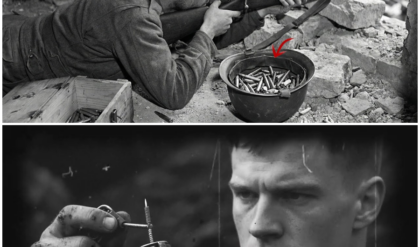

The Browning M1917, chambered in 3006, could sustain 450 rounds per minute for hours thanks to its water cooled barrel. Unlike Japanese light machine guns, which overheated quickly, the M1917 kept firing as long as ammunition belts arrived. Marines told stories of gunners holding the trigger until their hands blistered, cooling jackets steaming like kettles.

Yet, the gun kept spitting death. Japanese soldiers used to their type 96 or type 99 light machine guns that jammed or overheated in prolonged bursts were stunned. They had never imagined a weapon that could maintain such steady, crushing fire. Then there was the bigger nightmare, the Browning M250 caliber. Nicknamed Madus, it fired half-in bullets at 2,900 ft pers.

Able to tear through walls, trucks, and even thin armor. Mounted on tripods, tanks, aircraft, and landing craft, the M2 transformed the battlefield. Japanese soldiers hiding behind palm trees watched in horror as rounds splintered trunks into shards. Caves they thought safe collapsed under withering 50 caliber fire.

One survivor from Saipan recalled, “We believed we were behind stone, but the American bullets broke the stone.” The psychological impact was devastating. Japanese doctrine emphasized courage, bayonet charges, and close combat. But machine guns robbed these tactics of power. At Guadal Canal, night after night, Japanese commanders launched banzai charges, columns of shouting men surging toward American lines.

At first, the Marines were shaken, but when Browning machine guns opened, the charges dissolved into slaughter. Whole battalions vanished in minutes. One Marine officer described it bluntly. It was like mowing grass. Japanese survivors could not comprehend how Americans poured fire without pause, belt after belt, until no man was left standing.

One lesserk known fact, American logistics made this possible. Machine guns are hungry weapons devouring thousands of rounds in hours, but US supply lines delivered. On Guadal Canal, despite constant shortages of food and medicine, crates of ammunition still arrived. Marines sometimes joked they had more bullets than beans. Japanese soldiers, by contrast, often rationed ammunition.

five rounds per man, sometimes less. Their machine guns sputtered, then fell silent. The Americans never did. At Terawa in November 1943, Japanese defenders fortified the atole with bunkers and machine guns of their own. But when Marines stormed the beaches, Browning heavy machine guns mounted on amphibious tractors fired back with such volume that Japanese positions disappeared in plumes of sand and blood.

Survivors reported disbelief that a single American vehicle could unleash more fire than an entire platoon. When the Marines established their beach head, water cooled Brownings were set up immediately, fields of fire overlapping. Japanese counterattacks died before they reached the surf. The 50 caliber M2 became even more terrifying when mounted on aircraft.

Japanese soldiers on Buganville described watching P40 Warhawks and F4U Corsair’s strafe positions with six or eight heavy machine guns at once. Each pass unleashed thousands of rounds, ripping through bunkers, trenches, and even tanks. A Japanese lieutenant wrote, “The Americans fire from the sky with weapons stronger than our cannons.

We hide in caves, but even caves are not safe. On Ewima, the climax of firepower, browning heavy machine guns lined every ridge and beach. Marines advancing yard by yard brought them forward on tripods, clearing caves with fire so sustained that the ground itself seemed to tremble. Tank crews mounted multiple M2s, sweeping slopes with arcs of fire.

Survivors wrote of the hopelessness. Everywhere there is the sound of the big gun. We cannot move. We cannot stand. We cannot live. Another overlooked fact. Japanese soldiers were shocked at how Americans integrated machine guns into every unit. In a Japanese squad, the light machine gun was the centerpiece, supported by riflemen.

But American doctrine gave each squad rifle firepower and added heavy machine guns at the platoon and company level. This meant overlapping layers of automatic fire. Japanese attackers advancing on one gun often ran into two more. To them, it seemed endless. An inescapable web of bullets. The industrial arithmetic sealed the shock.

By 1945, America had produced over 2.5 million Browning machine guns of all types. Japan produced fewer than 100,000 light machine guns and even fewer heavy ones. American gunners trained relentlessly, firing thousands of rounds in practice before ever entering combat. Japanese gunners often lacked even enough ammunition for live training.

When battle came, the difference was catastrophic. Psychologically, heavy machine guns became symbols of American invincibility. Japanese survivors of battles like Pleu confessed that courage was useless. One wrote after capture, “We charged bravely, but the Americans had guns that never stopped.

It was as if they had more bullets than we had men.” Prisoners interrogated after Okinawa often repeated the same phrase. Their fire never ends. For American troops, the Browning machine gun was a lifeline. Marines pinned down by snipers called for heavy guns to sweep treetops. Soldiers advancing against bunkers watched tracers chew through embraasers.

Many credited their survival to the unyielding thunder of Madus. It became not just a weapon but a psychological comfort. When you heard her firing, one Marine said, you felt like nothing could get through. By the war’s end, Japanese soldiers who had once believed courage could overcome steel faced the bitter truth.

America’s heavy machine guns were more than weapons. They were factories at the front line, spewing bullets with mechanical inevitability. Against that tide, bravery dissolved into despair. For Private Watanabe on Guadal Canal, that first encounter with the Browning defined the war to come. He survived that day, crawling deeper into jungle shadows, but his squad was gone.

Years later, reflecting on the war, he admitted, “We thought Americans were soft, but their guns, their guns never rested. That was the end of.