They left her out there to die. Not fast, not loud, just slow and quiet. Like throwing a broken dog out in the heat and waiting for the sun to finish the job. It was July in Mojave, one of them months where the air don’t breathe back. Ridgerest lay still under the kind of sun that makes old wood split and horses go blind if they run too long.

Jack Mercer, 42, had lived through enough hell to know when something wasn’t right. He wasn’t soft, not after burying a brother, burning a house, and losing a woman who once called him home. But what he saw that day, that ain’t the kind of thing a man forgets. She was standing on the edge of his ranch.

Near the fence post he hadn’t mended in years, barefoot, dress soaked to the knees, a sack tied hard over her head, grain burlap, no slits, no mercy, wrists bound, rope cuts deep enough to shame barbed wire. And still, she didn’t move, didn’t run, didn’t scream. She just waited like she already knew no one was coming.

Now tell me, you ever seen something so wrong it makes your teeth ache? Jack stepped down from his horse. Didn’t say a damn word. Just walked slow like a man approaching a cliff edge he couldn’t see the bottom of. The girl whispered, voice so dry it cracked mid syllable. Please take them off. Not loud, not dramatic, just empty like the words were the last thing she owned.

Jack’s fingers, rough from fence posts and firewood, reached up to the knot. It was tied tight with hate. Took three whole minutes to undo. And when the sack dropped, what he saw underneath wasn’t cursed. It was 19 years of someone else’s cruelty. Wrapped in silence, Jack didn’t ask her name. Didn’t ask where she came from or what the hell happened.

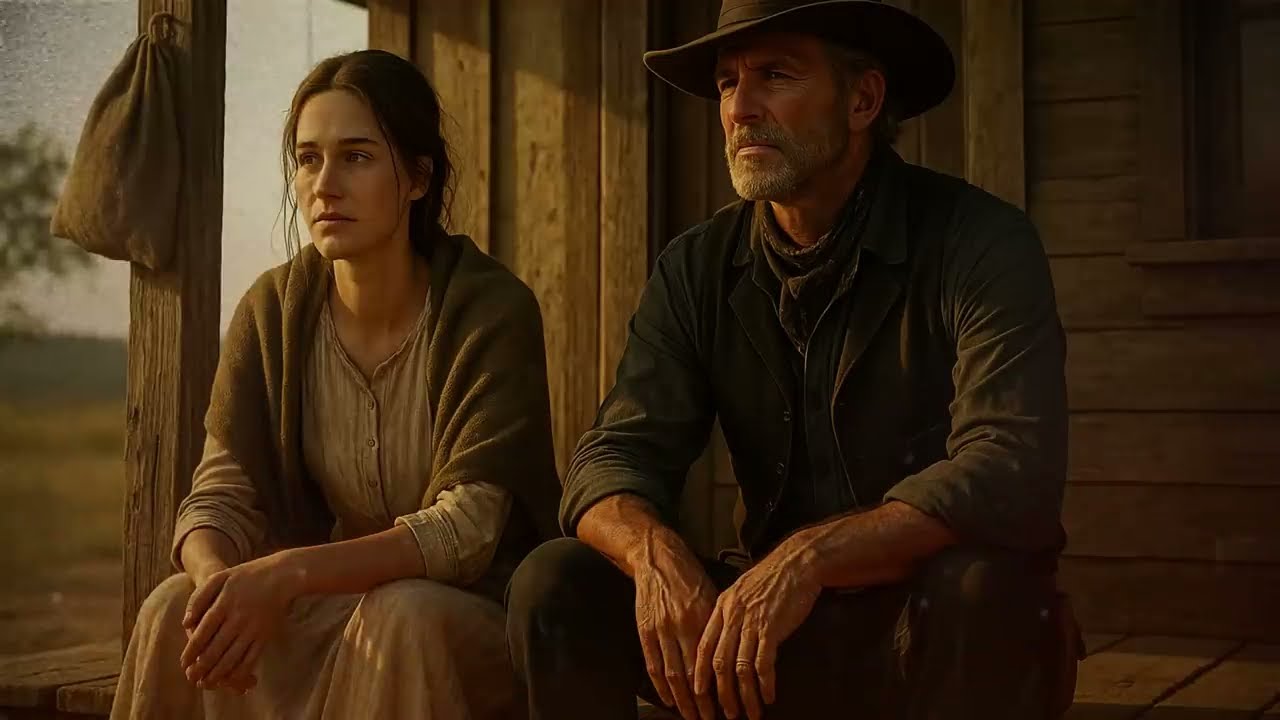

He just helped her up on the saddle, real gentlelike, and rode slow back to the cabin. The ride was quiet, but not awkward quiet. More like the kind of silence that shows up when two folks know they both seen too much. Back at the ranch, Jack poured her a tin cup of water. She drank it like it hurt, but she didn’t spill a drop.

He boiled a potato, left her the bigger half. Didn’t say why. Didn’t need to. She sat near the fire, wrapped in one of his old blankets. Didn’t speak for near 20 minutes. Jack didn’t push. Hell pushing ain’t never helped nobody open up. Not out here. Finally, she looked at him and said real soft. They said if a man looked too long, he’d get cursed.

Jack didn’t blink. Doesn’t sound like a curse. Sounds like cowards. She smiled. Small crooked, but it was something. Next morning, Jack found her hanging his shirts on the line. She wasn’t asking to stay, but she wasn’t asking to leave either. But word in a town like Ridgerest moves faster than a rattler in dry brush by sundown.

The saloon was buzzing with stories. Some said she was Comanche. Some said she was a witch. One old drunk even said she was a ghost Jack dug up and fell in love with. Jack didn’t give a damn what they thought. He had fences to mend, a horse with a limp, and now a girl with rope burns who flinched every time he coughed too loud.

But that evening, things changed. Two men on horseback came up the south road. Didn’t wave, didn’t smile, just sat there looking at the house like it owed them something. Jack stepped onto the porch, shotgun still hanging on the rack above the door. Inside, the girl went still, hands shaking, eyes wide, like she recognized the smell of these men without even seeing them. They hadn’t come to say hi.

And Jack knew if they were here now, more would follow. Jack didn’t recognize the two men. But he knew the type. Too clean for ranch hands, too quiet for travelers. And they sat their saddles like men who thought they owned whatever they looked at. The taller one tipped his hat. Looking for a girl, he said. red hair.

Where’s a sack? Jack didn’t blink. Haven’t seen her. The other one laughed low. She limped a little. Pretty if you can get past the silence inside, the girl was holding her breath. Hands gripped the edge of the table like it might float her away. Jack stepped down off the porch. Real calm. She ain’t here. You can ride on.

Thing is, the first man said, “She ain’t yours to keep now. That that did it.” Jack’s voice dropped low, but it hit like thunder. She ain’t anyone’s to keep. She’s not cattle. She’s not property. She’s a person. The men didn’t push further. Not yet. They turned their horses and rode off.

But the way they looked back told Jack one thing clear as day. They weren’t done. That night, the girl didn’t cry. She didn’t speak. She just sat by the fire holding a hawk feather she’d found near the fence earlier that morning. Funny thing about feathers, they always show up after storms. She looked at Jack, voice barely there. They’ll come back.

Maybe, he said. Next morning. She wasn’t hiding. She was walking the fence line in Jack’s old boots, shirt tucked in like she belonged. And when Jack asked if she wanted to stay, she didn’t say yes. She just said, “I’m tired of running.” Now, I’ll tell you something. If you followed this story this far, you’re the kind of person who believes people can change, who believes maybe the West didn’t kill all the kindness after all.

And if that’s you, you might want to stick around soon cuz the worst part of this story, the part that still haunts folks in Ridgerest, it’s coming up next. So go on, hit that little subscribe button and don’t miss how this ends. But trust me, it it’s worth the wait. They came back on the third night, not two this time. Four.

No lanterns, no greetings, just the sound of hooves. Slow, deliberate, like men who weren’t afraid of the dark. Jack heard them before they reached the gate. He always did. The way a man hears things after years of sleeping with one ear open. He stepped outside with the shotgun. Didn’t raise it. Didn’t need to. Not yet. A leader.

Same fella from before. Dismounted Grant Teller. That name had floated around border towns for years. Girls gone missing, cards marked, whiskey debts unpaid. Grant spit in the dirt. She belongs to the man who paid,” he said. Jack didn’t flinch. “She’s not property.” Grant stepped forward. “She’s a curse inside.” She heard every word.

But she didn’t curl up this time. She didn’t hide in corners or behind blankets. She opened the door barefoot, wrapped in Jack’s old quilt. Eyes steady. “You afraid of me?” she asked. The other men turned confused. Grant took a half step back before catching himself. You beat me, she said. You sold me. You left me in the dirt.

Said I’d bring ruin. But look who’s shaking now. Jack raised the shotgun. Calm a sunrise. You’ll ride out now, he said. And if I see you near this ranch again, you won’t ride out at all. They didn’t argue, didn’t threaten, just turned their horses and disappeared into the dark. And when they were gone, she sat on the porch, not crying, just breathing like someone who hadn’t in a long time.

And Jack, he just sat beside her. Didn’t say much, didn’t need to. After that night, things got quiet. Not the kind of quiet that comes from fear, but the kind you earn. The kind that settles in when storms pass and nothing breaks anymore. She didn’t hide. She didn’t flinch. She walked the fence lines at dawn like she owned the sun. And Jack, he didn’t ask questions.

He just watched like a man who knew he was watching something heal. Then one day, a wagon came up the trail. Slow, tired. Inside was a woman, dress faded, shoes cracked, a child asleep on her lap. She stepped down, looked at the girl, and whispered, “I was with you back in Texas before they split us.

” The girl didn’t cry. She just helped her down, cradled the child in her arms, and led them inside. That night, Jack didn’t say much. Just opened the barn door, pointed to the loft. There’s room. And that’s how it started. Not with fanfare, not with speeches, but with people who’d been thrown away. Deciding they weren’t done, they fixed up the old south room.

The new woman stitched quilts out of canvas and shirts. The girl planted herbs near the cotton tree. The kids sorted nails by size and sang when she thought no one heard. By spring, the town stopped whispering. Some folks waved. Some dropped off canned peaches. No one asked questions. She never wore the sack again.

But one day she pulled it from the drawer, walked to the edge of the pasture, and hung it from the fence. Let the wind take it. Didn’t chase it, didn’t look back. Now, let me ask you this. How many folks you know been treated like less than dirt and still got up and kept going? How many got told they were cursed and still found the courage to be kind? Sometimes the strongest people ain’t the loudest.

They’re the ones who don’t ask permission to matter. They just do. And if her story hit something in you. If it made you think of someone who survived more than they should have had to, go on and hit that like button. Maybe even subscribe. Because out here in the West, we don’t bury people in silence.

We tell their stories. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll stick around for the next ones.