December 24th, 1857, Christmas Eve, Savannah, Georgia. A date forever marked as the most brutal night in the history of slavery in the American South. Phyllis, that was the name of the woman who, armed with a firewood axe and a memory too wounded to forgive, forever changed the fate of the Chamberlain family, one of the wealthiest and most violent landowning dynasties in the region.

a house slave, 28 years old, born and raised on Riverbend Plantation, trained to serve at the table, to remain silent in the face of violence, and to smile even when bleeding on the inside. But that Christmas night, Phyllis did not serve. She did not stay silent. She did not obey. Phyllis killed.

With the same axe she had used for years to keep the big house warm, she butchered Jonathan, Paul, Samuel, and Thomas Chamberlain. Four brothers, four masters, four demons dressed as gentlemen. What began as another lavish Christmas dinner filled with laughter and wine turned into a storm of blood, steel, and vengeance. In less than 3 minutes, the heirs were reduced to pieces on the marble floor.

Phyllis wasn’t driven by madness. She was driven by love betrayed. Freedom denied, silence imposed, and the name Isaiah Carter, the man they promised to free and killed without warning. This is the true story of Phyllis, a slave who decided that Christmas would not be a night of peace, but of justice. Before we continue with the video, drop a comment telling us where you’re from and what time it is over there.

And don’t forget to subscribe to the channel. While the city glowed with Christmas candles, the slave quarters trembled in silence. The moon hung low over Savannah, swollen and pale, like an eye too tired to cry. Across the city, windows danced with candlelight. Fireplaces crackled in parlors trimmed with garlands.

Children dreamt of gifts behind warm quilts while their mothers basted turkeys and glazed hams. It was Christmas Eve 1857, a night of hymns and fat bellies, of polished shoes and silver cutlery. But in Riverbend Plantation, the air was different. There, the cold bit through wooden planks like teeth. The smell wasn’t roasted meat, but old sweat and damp cotton.

The only fire burned low in the slave quarters. Not enough to warm bones, only enough to see the rats pass. No songs, no laughter, just coughs, chains, and the whisper of wind slipping under the doors. Phyllis sat near the fire, her dress stiff with ash and lie. She looked like any other house slave, apron tied, head down, back straight, but her eyes, her eyes had stopped blinking. She was staring at the flames, but seeing something else, someone else, Isaiah. His face would not leave her.

His laugh, once bright as brass, now came to her like a drum beat beneath the earth. His last words, “Wait for me!” But he never came. They sold him two counties west to a man with no patience and a whip soaked in tobacco spit. He tried to escape the second week. They broke both his legs, made the others watch, then let the heat finish him off.

When the word came back, Phyllis didn’t cry. She cooked dinner like any other day. She scrubbed the floors. She pressed the Chamberlain brothers coats, and then she stopped being human. Not to them, she never was, but to herself. Earlier that evening, she chopped firewood behind the kitchen.

The axe handle had splinters, worn down by years of use. She tested its weight again. Swing, breathe, swing, listen. She wasn’t thinking of firewood. Inside the big house, the Chamberlain brothers were celebrating. Four men, all pale, tall, wreaking of rum and perfume. Jonathan, the oldest, believed himself a philosopher. He quoted Latin while ordering lashings. Paul II, preferred little girls.

Samuel III, was a man of God who led prayer before beatings. And Thomas, the youngest, had a temper so short he once shot a slave for sneezing during his sermon. Tonight they drank brandy and sang carols, a turkey roasted in the brick oven. Phyllis had basted it herself, fingers moving like memory. She had served the table.

She had bowed, nodded, smiled, but she had also counted one bottle, two. They were almost where she needed them. Back in the quarters, an old man named Elijah looked at her. “You quiet tonight, girl,” he muttered. “Phyllis didn’t turn, just said.” “Quiet don’t mean empty,” he grunted. “Christmas Eve ain’t no night for spirits to wander.” She finally looked at him. “That’s why they wander.

” The wind pushed against the door again, as if trying to listen. Behind her, tucked into a bundle of kindling was the axe, clean, heavy, waiting. Tomorrow the papers would call it savagery. The courts would call it madness. But tonight it was justice with a handle.

Because while Savannah sang to the birth of a child in Bethlehem, Phyllis was preparing a different kind of arrival, the rebirth of a woman who remembered everything. And when the clock struck midnight, one by one, the lights would go out on the farm. Before the fire in her hands, before the steel beneath her silence, there had been a promise. Small, soft, spoken like honey, but just as sticky and just as false.

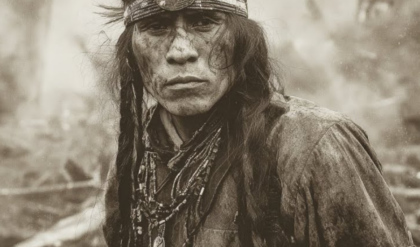

Phyllis remembered the day Isaiah arrived at Riverbend. He walked with shoulders squared, a rare posture among men who had learned to stoop young. His eyes were sharp, not rebellious, but not yet broken. He had the kind of presence that made others stand straighter when he passed, even if they didn’t know why. He was not born in chains, not entirely.

His mother had once been a freed woman until someone signed a paper that turned freedom into illusion and blood into property. In the beginning, Isaiah was sent to the fields. He worked hard without complaint. By the third week, he was helping break horses.

By the fifth, the overseer started calling him boy with a little less venom, not out of kindness, but because he saw usefulness. And by the second month, Isaiah was speaking with Phyllis behind the smokehouse in the dark where only the stars could hear. He spoke of Ohio, of clean air, of mornings without orders. He told her he would save enough someday, somehow to buy their freedom. Phyllis didn’t speak much.

She just listened. But every time he touched her hand, something buried inside her fluttered like wings against a cage. One evening, Jonathan Chamberlain called Phyllis into the parlor. The fire was lit, the curtains drawn, and the scent of cherry tobacco filled the air.

He poured himself a glass of port and stared at her with the same look he gave when inspecting a horse. “I’ve seen the way you and Isaiah look at each other,” he said, swirling the drink. Phyllis didn’t reply. “You want to be free?” he asked. “You keep working hard through Christmas. Keep your head down. Make the house shine and come spring,” he paused, smiling. “Maybe I’ll write the papers.

” He didn’t mention Isaiah again, but the implication hung in the air like smoke. Freedom not just for her, but for both. A future not under the yoke, but under their own roof. That night, Phyllis said nothing to Isaiah. She simply pressed her forehead to his chest and held him until the lanterns burned out.

For the first time in years, she let herself imagine yellow dresses and laughter, not followed by silence. she let herself believe. Two weeks later, Isaiah was gone, sold overnight. No warning, no goodbye. Phyllis found out from one of the older field hands, who had overheard Samuel Chamberlain bragging about the deal, said he got a fine price for a fine mule.

The man laughed when he said it. She went to Jonathan the next morning, face still, voice calm. “You said spring,” she murmured. Jonathan looked over the rim of his cup. “He wasn’t part of the bargain.” She stared at him a moment longer. “And me,” he smirked. Spring’s still coming. Be a good girl, Phyllis. She didn’t reply. She turned and left quietly.

But as she passed the kitchen doorway, her hand brushed the edge of the cleaver hanging beside the hearth. She let her fingers rest on the worn wood of the handle for just a second. Just enough. Days passed. Then came the story. Isaiah had tried to run. They caught him near a creek, dragging one bad foot. He’d broken free from chains, but not far enough.

The overseer at the new plantation was known for cruelty. They stripped him down, tied him to a tree, and took turns breaking him in front of the others, leg by leg, bone by bone. By the time he died, there was barely a face left to recognize. The news came like wind under the door. No one said it directly to Phyllis. They didn’t have to.

The way she folded the laundry that day, tighter, slower, like wrapping something sacred was enough. She didn’t cry, didn’t scream. But the next time she washed the Chamberlain brothers coats, she checked the inside seams where they kept their pocket watches. their knives.

She memorized the size of their boots, the way they smelled when they came home drunk, the creek of the second stair outside their rooms. She began rising earlier, going to bed later, working harder. No one noticed that the firewood was being chopped finer, cleaner. No one noticed that the axe was moved, cleaned, dried with more care. No one noticed how her eyes never followed the ground anymore. The promise had been broken.

But something else had taken its place. colder, older, patient like frost waiting beneath soil. Isaiah was gone, but Phyllis, Phyllis was still here, watching, waiting, and the axe no longer belonged to the firewood. It was just a tool, heavy, worn, smoothed by years of calloused hands and the sweat of backs that never got rest.

Phyllis had held that axe for seven winters, splitting logs, chopping fatwood, feeding the kitchen hearth that warmed the food of men who fed off her silence. But that morning, as frost covered the dead grass and the Christmas sun peaked over the pines, she lifted it like it was something more than wood and iron. She tested the grip, balanced it with one hand, swung low just once, and listened.

The sound it made wasn’t the thump of labor. It was the whisper of reckoning. The yard behind the kitchen was still quiet. Most of the others were indoors, preparing pies, plucking poultry, setting tables, and arranging garlands under the stern eyes of the Chamberlain wives. The frost hadn’t yet melted, and each breath left ghosts in the air. Phyllis stood alone. She swung again.

A thick log cracked down the center. Clean, efficient, no wasted motion. It would have seemed ordinary to anyone watching, a house servant doing her chore. But there was something in her stance, a stillness between the movements. As if she wasn’t just cutting wood, she was listening, remembering.

Each blow of the axe became a heartbeat in reverse. One for every lie she’d been fed, one for every scar Isaiah carried, one for each of the four men who would die before dawn. Later that morning, she returned to the house. Her apron was clean, her eyes lowered, her hands folded before her like a hymn.

To the Chamberlains, she was still the quiet one, the obedient house girl who never raised her voice, never challenged a command. Jonathan sat in the parlor, oiling his boots. Samuel was at the piano, humming a hymn between sips of whiskey. Paul watched the younger house girls move about the room like prey in a cage and Thomas. Thomas hadn’t come downstairs yet.

Phyllis moved between them like breath. She placed firewood beside the hearth. She lit candles. She dusted the frame where the portrait of their father hung. A man whose name was carved into deeds, slave ledgers, and tombstones alike. The Chamberlains were his legacy, molded in his image, arrogant, cruel, confident in their invincibility.

But none of them noticed that Phyllis’s hand lingered on the mantle. that her fingers traced the edges of the fire iron rack, that her eyes flicked briefly to the large key ring hanging near the back door. At midday, she returned to the quarters, not to rest.

She hadn’t rested in years, but to gather the things no one else would think to notice, a rag soaked in lard to muffle hinges, a spare apron to wrap the ax in, and a threadbear shaw that smelled of old smoke and bone dust. She tucked everything behind the stacked crates near the smokehouse, covered it with salted rags and fish barrels. She walked slowly, deliberately, never rushing, not because she feared being seen, but because she wanted to remember every step, every breath, every beat of her heart before it changed its rhythm forever. That evening, as the sun began to drop behind the pine line, Phyllis watched the Chamberlain brothers gather

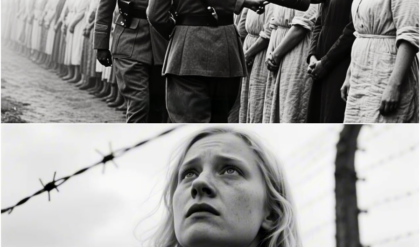

in the great room. They laughed loudly, drank brandy warmed by the fire. The scent of roasted duck filled the house. A string trio, slaves borrowed from a neighboring estate, played softly in the corner. Glass clinkedked, boots stomped. They were celebrating because they believed themselves untouchable because no one had ever told them otherwise.

Because no one like Phyllis had ever been given the chance. But something else filled the air that night. Not just music, not just smoke. It was memory, thick, bitter, and rising like sap through the floorboards. The axe remembered, and so did she. Tomorrow the walls would be soaked, but tonight they were still clean.

Villis moved through them with quiet grace, and with every step, the weight of the wrapped axe near the smokehouse pulled the future closer. Inch by inch, heartbeat by heartbeat. It was no longer just a tool. It was a name she hadn’t spoken aloud yet. But soon, the axe would speak for her. They wore their cruelty like fine coats, tailored, polished, passed down from their father, Jonathan, Paul, Samuel, and Thomas Chamberlain. Four brothers born into land, liquor, and lawlessness.

Sons of Colonel William Chamberlain, a man known across Georgia not for justice, but for how efficiently he could turn people into property. When he died, he left behind a house of brick, 400 acres of cane and cotton, and a legacy of blood dressed in wealth. Each brother had learned a different lesson from their father.

Each one carried it in his own way and each would soon pay for it. Jonathan was the eldest, 42, the thinker, the one who quoted scripture and Shakespeare while ordering punishments. He believed in order, not justice, not mercy. Order, a system with him at the top, and everyone else nailed beneath.

He took pride in his logic, in his restraint, in how cleanly he could command a man’s breaking without raising his voice. He once had a field hand whipped for stealing time, the crime, pausing too long to wipe his brow. Phyllis had served him the longest, watched him sip tea and discuss abolition like it was a far-off rumor, irrelevant and inconvenient.

He was the one who offered her the lie, that sweet spoken promise of freedom. His voice had been calm that day, assured, as if he believed his own deceit. Paul came next, 38. Slippery as oil, always smiling, always watching, he rarely raised his hand in violence. Not because he was gentler, but because his pleasures didn’t require bruises on the outside. Paul preferred girls young, unready, frightened.

He told them it was favor, that it was better to be chosen than ignored. Phyllis had kept distance from Paul for years, but she’d seen the aftermath in the kitchen. The girls too quiet, the bloodstained rags hidden behind the stove. She remembered a child named Elsie, 11, gone within weeks, claimed to have been sent north, but no wagon had ever come.

Samuel III was the preacher. 35. A man who wore a cross like armor and carried a Bible like a weapon. Every Sunday he read from the good book while the slaves stood in the dirt, heads down, hearing sermons about obedience and divine order. God made us masters, he’d say, to teach the rest their place. But his real scripture was pain.

He believed punishment was purification. That screaming was the soul shedding sin. He kept a ledger of offenses in his study, names, dates, infractions, number of lashes, neat, tidy, like accountancy of human suffering. He was the one who had tied Isaiah to the whipping post that night before he was sold. Phyllis hadn’t seen it, but she heard it.

Every crack of the whip like a nail hammered into her memory. Then came Thomas, youngest, 28. Thomas didn’t hide behind religion or charm. He was pure temper. A storm in boots and bourbon. He beat men for coughing too loud, punched horses in the face when they didn’t obey.

Once he fired a pistol at a slave child for crying during his card game, missed the head, shattered the girl’s arm. Unlike the others, Thomas didn’t believe in hierarchy or legacy. He believed in fear. It was the only language he spoke. He carried a pistol at all times, even in church. Once shot at his own brother during a drunken argument, laughed when he missed.

Phyllis knew Thomas would be the hardest, not to kill, but to control. Because men like him didn’t think. They lunged. They raged. They forced you to be faster than your grief. That night all four brothers sat in the parlor full of wine and roasted duck, speaking of profits, of new shipments, of which slave would fetch the highest price come spring.

They spoke of Phyllis as if she were a fixture, a broom leaning against the wall. One even joked about the way she moved. Like a shadow trained to pour, she heard every word, smiled once, just enough. She served them each their favorite slice of meat, topped off their drinks, took note of which one was already slurring, and then she stepped into the hallway where the light was low and the shadows long.

In the distance, a door creaked shut. The wind howled faintly beyond the pines. The fire popped inside the hearth, and Phyllis Phyllis began to count the minutes until midnight. four men, four debts, and one axe, sleeping quietly behind the smokehouse. She never prayed again after Isaiah.

The last time she’d closed her eyes and whispered to the sky, his body was still warm in her arms. Just days before they took him away. Since then, her lips had learned to stay shut. Not because she stopped believing, but because prayers hadn’t saved anyone. Not her mother. Not the baby she lost in the winter of 52. Not Isaiah. What she did now wasn’t prayer. It was remembrance.

names, dates, faces recited not to heaven but to herself. Phyllis sat on a low stool near the back pantry, her apron clean, her hands folded over her knees like a woman waiting to be summoned. The chamber behind her pulsed with drunken laughter and the shuffle of boots on polished wood. It would be soon. The wine had worked. The fire was low.

Outside the wind moved slow across the cane fields, brushing the long blades like hands over the backs of the forgotten. She closed her eyes and began the list. Elsie, Isaiah, Mama, Binta, Moses, Hector, Grace. One name for each step she would take through that house. One for each swing of the blade.

Each name await, each a drum beat in her chest. She was not alone. They were all with her now. She rose slowly. The kitchen clock clicked behind her, ticking toward midnight. The others were either asleep in the quarters or curled in corners, too afraid to lift their heads. No one questioned her movements anymore.

Not since she had become so perfectly predictable. She moved through the servant halls with steady steps, her shoes soft against the floorboards. Every candle she passed flickered as if recognizing her. Outside she reached behind the barrels into the hidden gap she’d prepared days earlier. Her hands found the cloth bundle. Unwrapped it.

The axe gleamed in the moonlight, not polished, but sharp. The kind of edge that only time and fury could grind. She tested the weight once more. Her arms didn’t tremble. They remembered, just as the axe did. Inside the house, the Chamberlain brothers were in different rooms now. Jonathan had retreated to his office, thumbming through his ledgers.

Paul had followed a girl upstairs, one too young to know what was coming. Samuel had passed out near the fireplace, still holding a glass of wine. And Thomas, restless, wandered the hall, pistol swinging lazily from his belt. They were scattered. Good. Phyllis had planned for that. Not in words, not on paper, but in bone, in silence, in the corners of her mind where rage lived like a coiled snake. She inhaled deeply through her nose. The air smelled of cinnamon, cedar, and smoke.

The smoke was from the kitchen fire, but she imagined it rising from something older. The kind of fire that once lit the way for runaways in the swamp, the kind of fire that signaled war. She stepped inside the back hallway. The floor creaked once and then held. She tightened her grip.

From this point forward, there would be no turning, no mercy, no last words, only the axe and the names. Grace, Thomas, Isaiah, Samuel, Elsie, Paul, Mama, Jonathan. She didn’t say them aloud. They pulsed in her chest. Outside, the final bell of the church began to toll for midnight. Inside, no one knew it would also toll for the end.

Phyllis took one more breath, not as a servant, not as a slave, but as a woman who remembered everything. The house had never been so loud or so blind. Laughter roared from the parlor like thunder over the cane fields. Bottles clinkedked, cards slapped on oak tables, boots thudded across rugs woven in distant lands. Outside the slave quarters flickered with quiet, oil lamps burning low, whispers buried under layers of fear and fatigue. But the big house, swollen with noise and wine, had no idea that the silence beyond its walls was watching.

Phyllis moved through that noise like fog. She brought out platters of roast duck and cornbread, refilled glasses, cleared bones left gnawed and bloodied on the edge of porcelain. Her feet made no sound on the floor. Her hands trembled only once, and not from fear, but from restraint, because everything was in place now.

The axe was hidden in the hallway linen chest beneath folded sheets. The doors were unlocked. The locks had been loosened earlier. The path was clear. She only needed time and darkness, and for each of them to be alone. Jonathan was the first to separate. He said the noise gave him headaches.

He left the parlor with a mutter, holding his ledger like scripture, always writing, always planning. Phyllis knew where he’d go, the office with the red rug and the iron key above the fireplace. She dusted it that morning. Paul had disappeared with a young house girl just after dessert. The girl hadn’t spoken all day.

Phyllis had watched her hands shake as she served the wine, had seen the way Paul’s palm lingered on her waist as they left the room. She was 15, maybe. Phyllis didn’t know her name. Samuel sat by the fire whispering scripture through lips stained red with port. He quoted lines about order, sin, obedience. None of the words reached God. His head lulled back on the chair, the Bible resting open on his lap. His fingers twitched.

He was slipping under. And Thomas, Thomas paced. He always paced when drunk, like a hound sniffing out trouble before it had a scent. His pistol swung at his side, still holstered, but loose. He’d punched a wall earlier, furious that the girl he’d wanted had escaped to the cook house. He’d shouted that someone would pay.

Phyllis had watched him from the shadows. She didn’t flinch. She’d spent too many years serving his anger in silver dishes to fear it now. By now, the house had dimmed. Most candles had burned low. The music had stopped. The string trio had been dismissed. The halls echoed with the kind of silence that doesn’t come from peace.

But from the moment before something breaks, Phyllis returned to the kitchen once more, washed her hands, folded the towel. She looked around. The knives were clean. The fire was low, everything exactly where it should be. She took the long hallway back toward the main house, steps slow, breathing calm. When she passed the window, she looked outside.

The moon was high now, cold, wide, watching. The same moon that had watched Isaiah scream, that had watched her mother crawl through blood after childbirth, that had seen every lash, every lie, every night she’d pretended not to hear the cries from upstairs. Tonight, it would watch her, too. But it would see something new.

At the foot of the stairs, she paused, listened. One man upstairs, one in the study, one unconscious by the fire, and Thomas, still roaming. She didn’t pray. She just reached into the linen chest, wrapped her fingers around the wooden handle, and lifted. The axe felt lighter than it ever had because it no longer carried wood. It carried memory.

And what Phyllis had to do now was not for freedom. It was for balance. The office smelled of pipe smoke, leather, and old ink. The scent of ledgers, of decisions made in quiet rooms, while others screamed elsewhere. Jonathan sat alone, as she knew he would. A half empty glass of brandy rested on the desk beside the plantation accounts.

He read with his boots propped on a stool, fingers tapping gently along the edge of the page. The oil lamp cast long shadows across his face, softening the lines that arrogance had carved into him over the years. Phyllis stood outside the door, silent. She held the axe low, wrapped in a kitchen cloth, still warm from the hearth.

She didn’t hesitate, not because it was easy, but because she had already done this in her mind over and over until it no longer felt like a beginning. It felt like a return. She stepped into the doorway. He didn’t look up. She stepped closer. He heard her now. Glanced toward the sound, eyes sluggish, unfocused.

Phyllis, he asked, voice dry from drink. Something wrong with the fire? She said nothing. She just stared, his brow furrowed, confused by the silence. He began to rise, and that’s when she stepped forward. One quick stride, both hands gripping the axe. The blade came down, not in rage, but in rhythm. A single arc.

The edge found the crown of his head with a sound like wet wood splitting. The body twitched. The glass of brandy tipped from the desk and shattered. Blood pulled across the ledges. The numbers bled with him. She did not look away. She stepped back once, watched his chest for movement. There was none. No breath, no voice, no more lies.

He had spoken of freedom like it was charity. Had held her hopes in one hand and the whip in the other. Now both hands hung useless at his sides. The lamp flickered. She turned it down. No need to draw attention yet. She closed the door gently behind her as she left as if he were only sleeping.

She moved through the hall again, breath steady, steps soft, one name struck, three to go. In the distance, thunder rumbled low across the horizon, but inside the house there was only silence, the kind that comes after a secret has finally spoken. Phyllis gripped the axe tighter. It was warm now, not with effort, with memory.

She passed the parlor where Samuel still slept, mouth open, Bible crumpled in his lap. Not yet. She needed him conscious. She needed him to see. Upstairs, Paul’s door creaked. A soft whimper from behind it. That would be next. But first, the girl. Phyllis climbed the stairs careful. Each board knew her weight. Each creek she had memorized. At the top, she paused.

The hallway stretched long, a corridor of ghosts and decisions. Behind the third door, she heard it. Paul’s voice low, coaxing, then silence. Then a shift in the bed. She tightened her jaw. Isaiah had called her strong. He never saw this part. She reached for the door, gripped the axe, swung it over her shoulder like a question only she could answer, and knocked.

The knock was gentle, almost polite. Paul didn’t answer right away. Inside the room, there was a shuffle, the sound of fabric moving, of fear being pressed into a corner. Phyllis heard him murmur something, then footsteps across the wooden floor. The door cracked open. Paul’s face appeared, lit only by the dim hallway lamp.

His shirt was half buttoned, hair tousled, eyes glinting with suspicion. And something else, that smug, sick charm he wore like perfume. Phyllis, he said, voice slick. You need something? She didn’t speak. She stepped forward and swung. The axe met bone with a sickening thud. Not the head. Not this time. The blow landed at the base of his neck where collar meets shoulder.

Paul screamed, staggered backward, arms flailing. Blood gushing across the floorboards like wine spilled at a cursed feast. Phyllis followed him in. She didn’t hesitate, didn’t pause. The second swing found his chest. The third crushed the ribs beneath it.

Paul tried to crawl, mouth gurgling nonsense, fingers reaching toward the hearth poker by the fireplace. Phyllis stepped on his hand, looked him in the eyes. Her name, she said, voice low, steady, was Elsie. The final blow came like thunder, and Paul Chamberlain stopped moving. In the corner of the room, the girl trembled under a blanket. She couldn’t have been older than 15.

Phyllis lowered the axe, breathing hard now, blood soaking her apron. She turned to the girl. The girl flinched wideeyed. Phyllis stepped closer, kneelled, voice soft. You don’t have to run. The girl stared at her like she wasn’t real, like she’d just seen a ghost tear open the earth. Phyllis reached out slowly, took the girl’s hand. Go to the cook house, she said. Stay with Auntie May.

Don’t open the door. The girl nodded, ran. Phyllis stood again, legs heavy, chest pounding. Two down. Back in the hall, the light felt different now. The axe dripped as she moved, footsteps behind her. She turned fast, just in time to see Samuel stumbling from the parlor, still holding the Bible, blinking at the blood on the floor. He froze when he saw her.

Phyllis, what is this? He slurred. Where’s Jonathan? What? What have you done? She said nothing. He looked at the axe at the trail of blood leading from Paul’s door, then at her eyes. No, he whispered. No, girl. Don’t you know what you’re doing? She stepped forward. He backed away. It’s Christmas, he pleaded. You can’t You can’t do this on his day.

She stopped, looked him dead in the eye. “His day came and went,” she said. “This one’s mine.” Samuel turned to run, made it to the top of the stairs, slipped, fell hard. His Bible flew from his hand, tumbled down the steps. Phyllis followed him one step at a time, axe in hand, calm as Sunday rain.

At the bottom, he lay groaning, blood on his mouth. He tried to speak, quoted scripture, but she wasn’t listening anymore. He’d preached forgiveness while ordering pain, sung hymns while others buried their children. Now his voice cracked like old wood. She raised the axe and ended the sermon. Three. Three down. Only Thomas remained.

The loudest, the crulest, the one who never hid what he was. Phyllis turned, walked through the hall, blood trailing behind her like ink on the final page of a book long overdue to close. Somewhere in the house, a door slammed. A scream not hers. Thomas had found a body. He was awake now, armed and hunting. Good. Let him come. She gripped the axe. The storm wasn’t over.

It was just beginning. The house was breathing now. Not with life, but with heat, blood, and something older. The kind of breath that rises from graves. The kind that knows names. Smoke hung low in the corridors. The oil lamps had burned down to a dim orange haze, casting shadows that moved like ghosts along the walls.

Blood painted the floorboards. Three bodies lay where power once sat. Jonathan in his chair, Paul in the bedroom, Samuel at the foot of the stairs. Only one remained, and he was ready to kill. Thomas Chamberlain’s boots thundered through the house, each step a threat. He called her name now, not quiet, not cautious. Phyllis, it echoed. Come out, you damn witch.

You think I don’t know what you done? She heard the of his pistol. You hear me? I’ll shoot you slow. He was hunting. But the thing he didn’t understand, the thing none of them had was that Phyllis hadn’t run. She hadn’t hidden. She was waiting because Thomas wasn’t a surprise. He was the final obligation. She stepped into the dining room.

The long table was still set. Silver forks, crystal glasses, the duck halfeaten, wine bottles half drained. The fire had died down. Ashes glowed faintly in the hearth. She walked to the head of the table and sat. Placed the axe beside her on the polished wood. The blood had dried now, black around the handle. Her hands were steady, her breathing calm.

She faced the hallway and waited. It didn’t take long. Thomas stormed in, eyes wild, pistol raised, shirt open, face red from rage and drink. He saw her sitting there, quiet as stone, his lip curled. You think this is over? She didn’t answer. Get up, he spat. She stayed seated. I said, “Get.

” She stood fast and that motion was enough. He fired. The shot missed, the bullet thudding into the chair behind her. She didn’t flinch. He cursed. Tried to reload. Too late. She crossed the room in three strides. He raised his arm to block her. The axe came down, not once, but again and again. Not wild, not angry, precise.

Thomas screamed, fell, tried to crawl. She followed him to the floor. This time, she didn’t say a word. When it was done, the only sound was the crackling of dying embers. Phyllis stood in the center of the room, soaked to her elbows, her apron red, the blade dripping onto the marble tiles. All four were gone now. The Chamberlain name choked by its own root.

She looked at the feast they’d left behind. the duck, the silver, the wine, all untouched by justice until now. She picked up a glass, poured a small measure of red wine, and sat again at the head of the table. The blood on her hands clashed with the crystal, but she raised it anyway, not in celebration. In memory, for Isaiah, for Elsie, for her mother, for the ones whose names had been swallowed by silence, she drank alone.

When the morning light broke through the windows, it found her still sitting there, still calm, eyes open, not afraid, not finished, only free. Not because the law would spare her, it wouldn’t, but because the truth had finally spoken. And in that silence, after screams, after steel, there was peace.

The kind you don’t find in prayers, only in reckoning. They came for her just after sunrise. A neighbor had seen the smoke and sent a rider. The sheriff arrived with six men, all armed, all pale. When they stepped into Riverbend, the silence was thick, like walking into a church after the last hymn. They found the bodies where she left them.

Jonathan slumped over his books. Paul in his blood soaked bed. Samuel with his Bible open to Exodus. Thomas sprawled across the dining room floor, pistol still in hand, eyes wide like he’d seen judgment walk into the room with a kitchen apron and an axe. And Phyllis, she was still at the table, back straight, hands folded, waiting.

They didn’t ask questions. They didn’t read her rights. They bound her wrists with rope tight enough to bleed and dragged her outside. As they led her down the steps, she turned her face to the fields. She looked out over the rows of Cain, now brittle and frozen in the winter air.

The same fields where Isaiah once sang to make the labor bearable, where children had been born in the dirt, and old men had died standing, fields that had swallowed screams for decades. Now they whispered something different, her name. Word spread fast. By nightfall, the city of Savannah was already ablaze with gossip. The Riverbend Massacre, they called it.

Four white men butchered by a house servant. The newspapers didn’t print her full name, just the phyis. They called her mad, said it was sudden, but the people in the quarters knew better. In hushed tones behind cook fires and well buckets, they spoke of her with awe, with fear, with reverence. Her story traveled faster than any whip.

The girl who didn’t run, who didn’t scream, who turned the axe around and wrote a different ending. The trial lasted two days. No defense, no mercy. The courtroom smelled of ink and sweat and sawdust. The jury took 30 minutes guilty. They sentenced her to hang. In the jail cell, Phyllis didn’t beg, didn’t speak. She sat by the window where a sliver of sky peaked through rusted bars.

Every now and then she would close her eyes, not to dream, but to listen to names, to footsteps, to the sound of chains beginning to loosen. On the day of her execution, they dressed her in white. They said it was tradition. They said it was proper. They didn’t understand what they were doing because white was not their color.

It belonged to her now. To the woman who walked to the gallows like it was a wedding altar, like she wasn’t ending something, but sealing it. The crowd watched in silence. Some jered, some wept, some couldn’t look away. When they asked if she had last words, she looked straight ahead and said, “I only did what they taught me.

” And then she stepped forward. But Phyllis didn’t die that day. Her breath may have stopped. Her heart may have stilled, but her story, her story sharpened. It traveled the coast by whisper down into the Carolinas, into the fields of Alabama, through the rice swamps of Louisiana.

Her name was spoken under breath, carved into trees, sewn into lullabibis passed between mothers and daughters. She became more than a woman. She became reminder that even the quiet ones remember, that even the bound ones can cut deep, that even the darkest night can carry a blade. They tried to bury her beneath shame, but she was already planted in memory, and memory grows wild.

If this story burned something inside you, it’s because it wasn’t told in vain. Subscribe, leave your mark, and share it with those who carry in their blood the memory of those who dared to fight