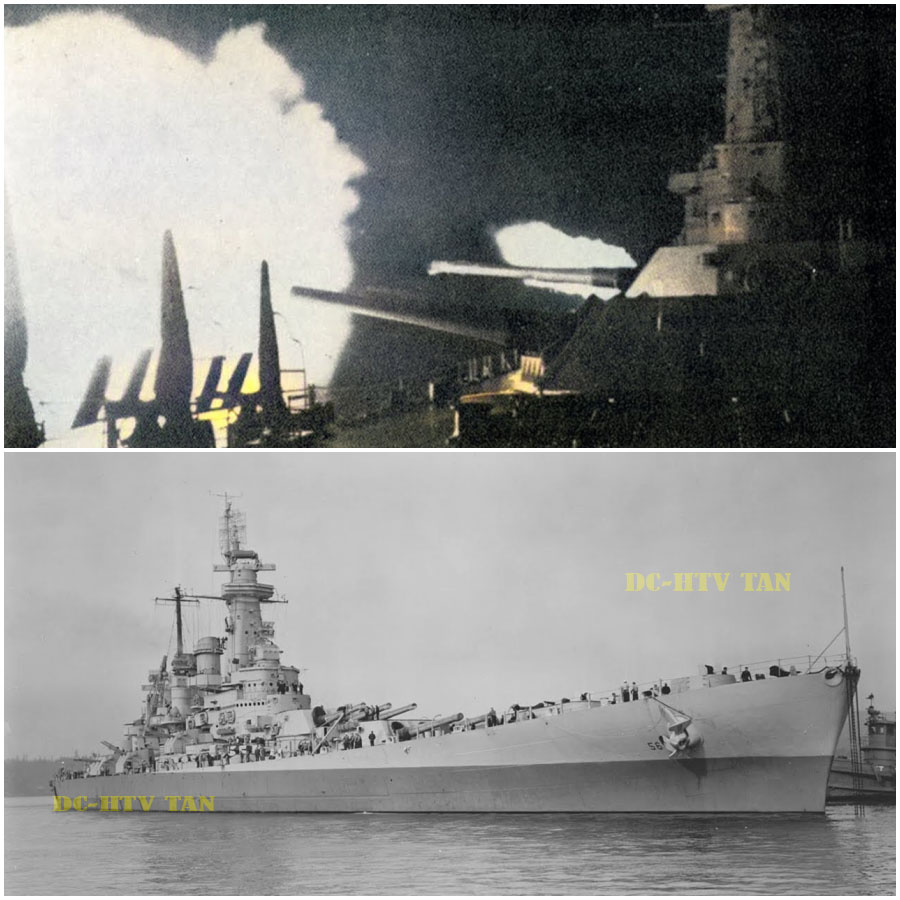

USS Washington Sank Japanese Battleship At Night With 9 Hits In 7 Minutes Using Radar….

At 0100 hours on November 15th, 1942, USS Washington’s radar operators watched a large contact appear on their SG surface search radar scope, range 8,400 yd, bearing 330°. The target was a battleship. She was moving slowly through Iron Bottom Sound, unaware that American guns were tracking her through the darkness.

Four American destroyers were already sinking or burning. USS South Dakota, the other battleship in Task Force 64, had been battered by Japanese gunfire after electrical failures knocked out her systems. Japanese search lights swept the water, searching for more targets, but they couldn’t find USS Washington.

The Japanese battleship Kiroshima had no radar. Her lookout strained to see through pitch darkness. Her optical rangefinders were useless without light. Her fire control officers had no idea an American battleship was less than 5 mi away. Guns trained on their ship, waiting for to the order to fire.

On Washington’s bridge, Rear Admiral Willis Augustus Lee stood next to Captain Glenn Benson Davis. Lee had been tracking the Japanese force on radar for 20 minutes. He knew exactly where every enemy ship was. The Japanese knew nothing. Lee had spent years preparing for this moment. He understood radar better than any flag officer in the United States Navy.

Now he would prove that electronics could defeat experience, training, and superior numbers. What happened in the next 7 minutes would change naval warfare forever. Night naval combat in 1942 was dominated by the Imperial Japanese Navy. For two decades, the Japanese had perfected tactics that made darkness their ally. Intensive training in low light conditions. Superior optical equipment.

Aggressive doctrine built around rapid torpedo attacks and close-range gunnery. Japanese destroyermen practiced night maneuvers until they could fight blind. Their commanders understood a fundamental truth. Darkness neutralized American advantages in firepower and industrial strength.

This doctrine had produced devastating victories. In August 1942, at the Battle of Seavo Island, Japanese cruisers surprised an Allied force and sank four heavy cruisers in 32 minutes. American ships had early radar systems, but commanders didn’t trust the technology. By the time Lookouts made visual identification, Japanese long lance torpedoes were already in the water.

The battle became a case study in what went wrong when radar was available but not properly used. USS Chicago had SC air search radar. The operator detected contacts at 43,000 yd, but the information took too long to reach the bridge. By the time the captain was informed, Japanese ships were already within visual range. The radar warning provided no advantage.

USS Ralph Tolbert, serving as a radar picket, detected Japanese ships, but reported them as friendly. The formation commander didn’t trust the radar data and didn’t order his ships to battle stations. The Japanese achieved complete surprise despite American radar detecting them miles away. In October at Cape Esperance, American forces achieved surprise using radar, but then lost control when the formation maneuvered into confusion. Rear Admiral Norman Scott had positioned his cruisers and destroyers in column formation. When

radar detected Japanese ships, Scott maneuvered to cross their tea, a classic tactical advantage. But in darkness, with ships maneuvering independently, the formation fell apart. Ships fired at contacts without knowing if they were friendly or enemy. USS Duncan engaged what she thought were Japanese ships. Some were friendly.

Duncan was hit by American shells, then hit by Japanese shells and sank. USS Boise was illuminated by Japanese search lights and took multiple hits before American ships could support her. The Americans won tactically, sinking a Japanese heavy cruiser and destroyer. But the battle revealed how easily radar advantages could be lost through poor coordination.

On November 13th, the first phase of the naval battle of Guadal Canal became a point blank brawl. American cruisers and destroyers engaged Japanese battleships at ranges under 3,000 yards. Ships fired at muzzle flashes. Search lights blinded gun crews. USS Atlanta took 19 shell hits and a torpedo.

USS Juno limped away damaged only to be torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine hours later. Rear Admiral Daniel Callahan and Rear Admiral Norman Scott both died in the action. They were the only two American admirals killed in surface combat during the entire Pacific War. The Americans had stopped the Japanese bombardment of Henderson Field, but at catastrophic cost.

Four destroyers sunk, two light cruisers sunk, multiple ships damaged, over 700 American sailors dead. The tactical victory came at a price that couldn’t be sustained. The cruiser force was shattered. Most at surviving ships needed repairs. Henderson Field had been saved for one more night, but the Japanese were coming back.

The Japanese lost battleship Hay, crippled in the engagement and finished by aircraft on November 13th and two destroyers, but they were preparing another attempt. Vice Admiral Noatake Condo was bringing battleship Kiroshima South with cruisers and destroyers to shell Henderson Field on the night of November 14th.

If the airfield was destroyed, Japanese reinforcements could land unopposed and retake Guadal Canal. The strategic situation was desperate. Guadal Canal represented the first American offensive of the Pacific War. If it failed, the entire strategy of island hopping toward Japan would be called into question. The Marines on Guadal Canal were exhausted. They’d been fighting for 3 months with inadequate supplies and constant Japanese attacks.

Henderson Field was their lifeline. Aircraft from Henderson provided air cover for supply ships and attacked Japanese reinforcement convoys. Without Henderson, the Marines couldn’t hold. Admiral William Holsey had almost nothing left to stop Condo’s bombardment force. The cruiser force was shattered.

He had one operational aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise, but carrier aircraft couldn’t fight at night. Hse option was to strip Enterprise of her battleship escorts and send them into Iron Bottom Sound for another night engagement. It was a calculated risk. If the battleships were sunk, Enterprise would be vulnerable. But if Henderson Field was destroyed, Guadal Canal would be lost anyway. The problem was that night engagements favored the Japanese.

American ships had better radar than they’d had at Tsavo Island or Cape Espirants, but radar alone hadn’t prevented disasters. The technology had to be used correctly. It had to be integrated into tactics and command decisions. Most American flag officers in November 1942 still thought of radar as an interesting experimental tool, not a weapon that could dominate combat.

They’d been trained in an era when visual spotting and optical rangefinders were the only way to fight. Radar challenged decades of doctrine and experience. Most admirals were cautious about relying on it completely. Admiral Willis Lee was different. Lee understood radar because he’d studied it. He’d worked with engineers developing fire control systems.

He’d examined British reports on radar directed gunnery. He trained his crews to fight using radar as their primary sensor. When other admirals said radar was unproven, Lee said radar would decide who controlled the Pacific. Willis Augustus Lee was 54 years old in November 1942.

Born in Kentucky in 1888, he graduated from the Naval Academy in 1908. His expertise wasn’t in traditional naval skills. Lee was a marksman. At the 1920 Antworp Olympics in Belgium, he won seven medals in shooting competitions, five gold, one silver, one bronze. He was the most successful athlete at those games.

His Olympic performance remained a record for 60 years until it was equaled in 1980. His specialty was longrange rifle shooting where tiny variations in wind, temperature, and distance determined hits or misses. Lee understood that hitting targets at distance required precise measurement and calculation. Small errors accumulated over range. Wind drift had to be calculated. Temperature affected powder burn rates. Barometric pressure affected bullet trajectory.

Lee became expert at measuring all these variables and incorporating them into his shooting. Lee understood precision. He saw battleship guns as instruments that required the same attention to variables that rifle shooting demanded. Range, speed, wind, ship motion, shell ballistics. Every factor had to be calculated correctly.

For decades, navies had relied on optical rangefinders and visual spotting to provide that data. Lee recognized that radar could provide better data more accurately. Optical rangefinders measured range by comparing images from two lenses separated by several meters. The operator adjusted the images until they aligned, then read range from a scale.

The process required good visibility, steady hands, and practice. Accuracy was typically 1% of range at best. At 10,000 y, the error could be 100 yard or more. In darkness or poor visibility, optical rangefinders were nearly useless. Radar measured range by timing radio wave reflections.

Radio waves traveled at the speed of light. The radar transmitted a pulse, measured how long until the echo returned, and calculated range from the time delay. The measurement was electronic, instantaneous, and unaffected by darkness, smoke, or weather. The Mark III fire control radar on Washington could measure range to within 40 yard plus.1% of range.

At 10,000 yd, the error was less than 54 yd. This was twice as accurate as optical rangefinders in daylight and infinitely better than optical rangefinders at night. Between the wars, Lee served as director of fleet training at the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. He worked on gunnery development and fire control systems.

When radar technology emerged in the late 1930s, Lee immediately understood its implications. Radar could measure range more accurately than optical rangefinders. Radar could track targets in darkness, fog, or smoke. Radar could see over the horizon. If properly integrated with fire control computers, radar could revolutionize naval gunnery. Lee pushed for radar development and integration into fleet operations.

He studied British reports on radar use in the Atlantic. He attended technical briefings on radar equipment. He visited research facilities developing radar systems. By the time radar equipped ships began deploying to the fleet in 1941 and 42, Lee probably understood radar capabilities better than anyone at flag rank.

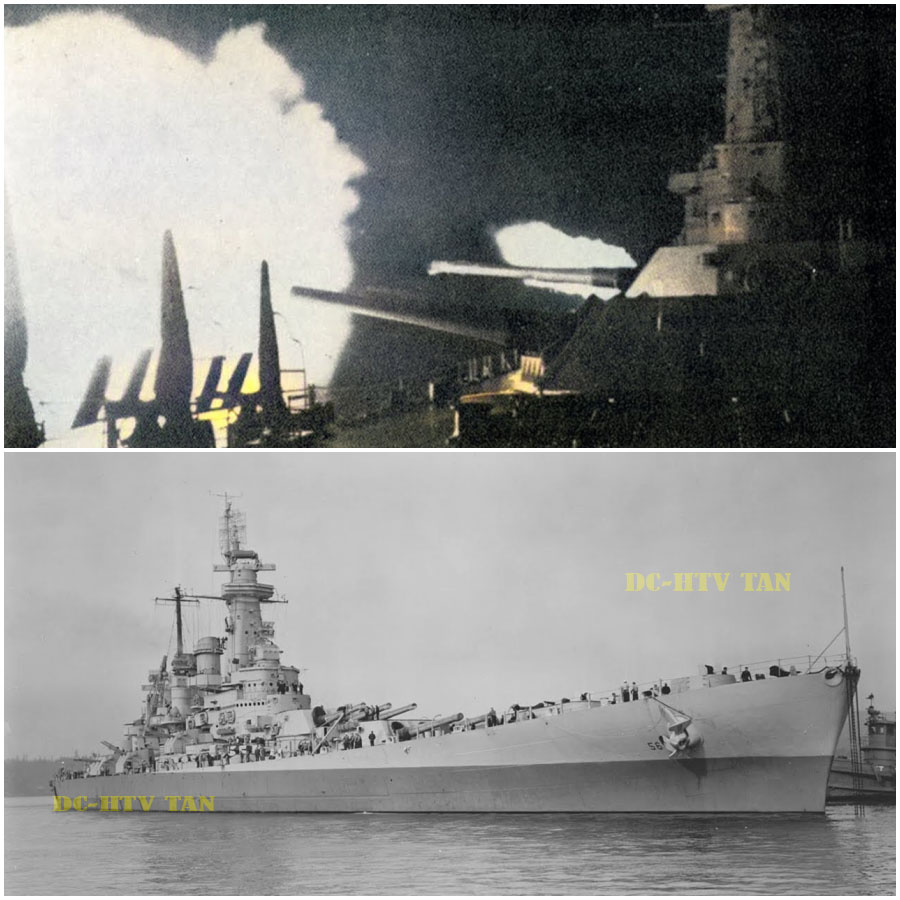

Lee was given command of battleship division 6 in August 1942. The division consisted of two new North Carolina class battleships, USS Washington and USS South Dakota. Both ships carried nine 16-in guns in three triple turrets. Both had advanced radar systems. Both were fast, capable of 28 knots. Lee made Washington his flagship and immediately began training his crews in radar directed gunnery. Lee’s approach was radical.

Traditional doctrine said radar was a backup to visual systems. Use radar to find targets, then switch to optical control for firing. Lee made radar the primary sensor. He reorganized Washington’s fire control procedures. So, radar operators worked directly with the gun directors and plotting rooms.

Information flowed from radar to fire control without going through layers of bridge officers who might question or delay the data. Lee drilled his crews constantly. Track targets on radar. Calculate firing solutions from radar data. Fire without visual confirmation. Trust the electronics. USS Washington fired her main battery at night twice in January 1942 during training exercises in Casco Bay, Maine.

Both times the gunnery was directed entirely by radar. No visual sighting of the targets, no optical range finding, just radar providing data to the fire control computer. The results convinced Lee that radar could control accurate fire at ranges where visual spotting was impossible. Washington’s shells landed close enough to the target sleds that Lee knew the system worked, but convincing the Navy required proving it in combat against a shooting enemy.

Training exercises were one thing. Combat with ships maneuvering and shooting back was entirely different. The test came on November 14th, 1942. Intelligence reports indicated Vice Admiral Noutake Condo was bringing a bombardment force to Guadal Canal. The force included battleship Kirishima, heavy cruisers Atago and Takao, light cruisers Sai and Nagara, and nine destroyers. Their mission was to destroy Henderson Field and land reinforcements.

The Japanese had tried this twice in the previous two nights and been turned back both times. Now they were coming with overwhelming force. Holy ordered Lee to take Task Force 64 and stop them. Lee had USS Washington, USS South Dakota, and four destroyers, USS Walk, USS Benham, USS Preston, and USS Gwyn. It was everything available.

Most other American warships in the area were damaged or low on fuel or ammunition. Lee knew the odds. Six ships against one battleship, four cruisers, and nine destroyers. The Japanese had overwhelming numerical superiority. They had more guns. They had more torpedoes. They had better night fighting experience.

They had the tactical initiative because they knew where they were going and when they needed to arrive. Lee would have to intercept them in waters. The Japanese knew intimately. Lee’s only advantage was radar. He intended to use it completely. His plan was simple. Position his force to intercept the Japanese as they approached Guadal Canal.

Use the destroyers as a screen to deal with Japanese destroyers and absorb the initial torpedo attacks. Keep the battleships back in darkness where Japanese visual spotting couldn’t find them. Use radar to track Japanese capital ships. Wait until the range was right, then open fire with radar directed salvos. The plan required perfect radar performance, perfect fire control calculations, and enough luck to avoid being hit by torpedoes or found by Japanese search lights.

Lee accepted these risks because any other approach meant fighting on Japanese terms, and fighting on Japanese terms meant losing. Task Force 64 approached Guadal Canal from the south on the afternoon of November 14th. Japanese reconnaissance aircraft spotted the formation and reported the sighting. The Japanese identified the force as one battleship, one cruiser, and four destroyers.

The identification was wrong, but close enough to alert Condo that American ships were in the area. Both sides knew a battle was coming. The question was who would gain advantage when the fighting started. At 2300 hours, Lee’s force rounded the western tip of Guadal Canal and headed north into Iron Bottom Sound.

The passage between Guadal Canal and Tsavo Island was about 8 mi wide. It was a confined space for battleship operations. Maneuvering room was limited. The water was filled with wrecks from previous battles. Survivors from earlier engagements were still in the water on rafts. The tactical situation was as bad as it could be for capital ships. But Lee had no choice.

If he stayed outside the sound, the Japanese would bombard Henderson Field unopposed. He had to engage them here. The night was dark. No moon. Low clouds blocked starlight. Visibility was less than one mile. The sea was f calm with a light chop. The air was hot and humid. Temperature was about 85°. The smell of jungle vegetation drifted across the water from Guadal Canal.

Occasional lightning flashed in distant thunderstorms. It was perfect weather for radar and terrible weather for visual spotting. Washington’s SG radar began picking up contacts beyond Tsavo Island at 2305 hours. Multiple groups of ships moving south. Lee watched the radar plot display. He counted contacts.

More than a dozen vessels in three groups. The Japanese bombardment force was approaching on schedule. Lee positioned his destroyers in line ahead of the two battleships. Walker, Benham, Preston, Gwyn. The destroyers would screen against torpedo attacks and engage enemy destroyers. The battleships would hang back and use their radar advantage to engage the larger enemy units from distance. Lee sent a message over the TBS radio to all ships.

This is Lee. We’re going into a big fight. Keep your heads. Stay alert. Trust your instruments. The technology that gave Washington her advantage had a remarkable history. Radar development in the United States began in the 1930s, but early systems were primitive. The breakthrough came from Britain.

In September 1940, a British technical mission arrived in the United States carrying a black box containing the cavity magnetron. This device could generate microwave frequency radio waves at power levels useful for radar. British scientists had invented it at Birmingham University. They shared the technology with America in exchange for American industrial capacity to mass-roduce radar systems.

The radiation laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology received the Magnetron in November 1940. Within months, engineers developed the first microwave radar prototypes. The SG Surface Search radar emerged from this work. It operated at approximately 3,000 megahertz using 10 cm wavelength. This was revolutionary.

Earlier radars used wavelengths measured in meters. The SC air search radar that many ships carried operated at 200 megahertz with a wavelength of 1.5 m. The shorter wavelength of the SG provided much better resolution. Contacts appeared as distinct points rather than fuzzy blobs.

The SG had another innovation, the plan position indicator display. Previous radars showed returns as spikes on an oscilloscope. The operator watched a horizontal line sweep across the screen. When the radar pulse hit something, a spike appeared on the line. The operator had to interpret the spike height and position to determine bearing and range. It required training and concentration. The PPI display was completely different.

It was a circular screen 9 in in diameter showing a map-like view. Washington appeared at the center as a bright dot. North was at the top. Contacts appeared as bright points of light at their actual bearing range relative to Washington. The display updated continuously as the antenna rotated at 15 revolutions per minute. An operator could see the entire tactical situation at a glance. Formation positions were obvious.

Contact courses could be determined by watching how the points moved. Multiple contacts were easy to track. It was intuitive and required less training than the oscilloscope displays. USS Augusta received the first operational SG radar in April 1942.

Washington received hers during her August 1942 refit at Philadelphia Navy Yard. By November, fewer than 50 American warships had SG radar. It was still cuttingedge technology. Many officers viewed it skeptically. The equipment was complex and could malfunction. The vacuum tubes failed regularly and had to be replaced. The antenna motors sometimes jammed. In rough seas, the mast head motion could affect the antenna position.

Officers who’d served their entire careers without radar weren’t convinced it was worth depending on. The SG antenna was mounted on the forward face of Washington’s main tower structure. The antenna was a rectangular frame about 2 feet by 3 ft containing the transmitter and receiver. It rotated continuously, scanning 360°.

The mounting position on the forward tower gave excellent forward and side coverage, but created a blind sector to the rear. Contacts directly a stern might not be detected. Lee accepted this limitation because most contacts would be ahead of Washington as she advanced into the engagement area. Maximum range on battleship-sized targets was approximately 30 mi in good conditions.

Smaller ships like destroyers could be detected at 15 to 18 mi. Light cruisers appeared at around 20 m. The bearing accuracy was within one degree. Range accuracy was within 100 yards at maximum range, improving to within 50 yard at closer ranges. These were impressive specifications, but the real advantage was that radar worked in complete darkness.

Visual lookouts were limited to a mile or less in these conditions. Radar could see six to eight times farther. Washington also carried Mark III fire control radar on her main battery directors. Two Mark 38 directors controlled the main battery. One director was mounted on top of the forward tower structure. The second was mounted on a tower aft of the second funnel. Each director had a Mark III radar antenna mounted directly on it.

The Mark III operated at a different frequency than the SG, approximately 100 megahertz. It was specifically designed for gun laying, not search. The antenna was smaller and focused its energy in a narrow beam. This gave precise ranging but covered only the area where the director was pointed.

The Mark III measured range with exceptional accuracy within 40 yard plus.1% of the range. At 8,000 y the total error was less than 50 yard. At 15,000 y the error was about 190 y. This was far better than optical rangefinders. Navy optical rangefinders were typically 26 ft long using the maximum separation possible on a ship.

In ideal daylight conditions with a clear target, a skilled operator might achieve 1% ranging accuracy. At 10,000 yard, that meant errors of 100 yard. At night with a dark target, errors could be several hundred yard. Many times the optical rangefinder simply couldn’t get a reading at all. The Mark III radar worked in any visibility conditions and provided consistent, accurate ranging.

The Mark III fed range data to the Mark 8 rangeeper, an analog mechanical computer weighing several tons. The rangeeper was installed in the plotting room below the armored deck. It was essentially a room-sized calculator built from gears, cams, and servo motors. The machine was about 12 ft long, 6 feet wide, and 7 ft tall. It required three operators to input data and monitor its operation.

The rangekeeper accepted inputs for own ship course and speed, target bearing, target range, target course, target speed, wind direction, wind speed, air temperature, and dozens of other variables affecting shell trajectory. From these inputs, it calculated where to point the guns. So shells fired now would intersect with the targets future position when they arrived.

The calculation had to account for shell flight time, typically 20 to 30 seconds. During that time, both Washington and the target would move. The shells would follow a ballistic arc affected by wind, air density, and the Earth’s rotation. All these factors had to be continuously recalculated. The rangekeeper updated continuously as radar provided new range data every few seconds. The computer recalculated as Washington maneuvered.

The computer compensated for the change in bearing and relative motion. The gun orders went electronically to the turrets where motors trained the guns in bearing and elevated the barrels. The entire process from radar measurement to gunpointing took seconds.

Human rangefinder operators and manual calculators needed minutes to achieve the same result, assuming they could see the target at all. The system worked when properly integrated, but it had limitations that Lee understood perfectly. The Mark III radar couldn’t distinguish shell splashes from the target return. During daylight gunnery, spotters in the directors watched where shells landed through optical instruments. They called corrections, up, down, left, right.

The rangekeeper adjusted the solution and the next salvo landed closer. This process of firing and spotting produced accurate shooting within a few salvos. In darkness, spotting was impossible. Washington would fire calculated salvos without being able to observe where they landed.

The only feedback would be if shells hit and started fires visible to lookouts. Otherwise, Lee would simply trust that the radar ranging was accurate and the fire control solution was correct. This was the gamble. Lee was betting everything on electronics that had never been fully tested in combat this way. If the radar lost track of the target, the guns would fire at empty ocean.

If the fire control computer made an error in the calculations, shells would miss by hundreds of yards. If Japanese ships maneuvered unpredictably, the solutions would be wrong by the time the shells arrived. If the radar data was slightly off, the entire firing solution would be degraded. Lee accepted these risks because fighting without radar meant certain blindness.

Fighting with radar meant at least having a chance to see and shoot first. In night combat, shooting first usually meant winning. At 2317 hours, Washington’s SG radar detected multiple contacts emerging from behind Tsavo Island, range 18,000 yards. The contacts were moving south in two groups. Lee ordered his formation to battle stations. General quarters had already been set hours earlier, but Lee’s message emphasized that contact was imminent.

The four destroyers were arrayed in column ahead of the battleships. Walker leading, then Benham, Preston, and Gwyn. The destroyers were spaced about 600 yardds apart. Washington followed about 2,000 yards behind Gwyn. South Dakota was supposed to follow Washington by another 2,000 yd, but Captain Gat maneuvered independently, and South Dakota’s position varied throughout the engagement.

Commander Thomas Fraser on Walker had the most advanced radar in the destroyer force. His SG radar, similar to Washington’s, picked up the Japanese destroyer screen at 12,000 yd. Fraser was an experienced destroyer commander who understood radar capabilities. He recognized the contacts as enemy destroyers and reported to Lee.

Fraser requested permission to launch torpedoes at the torpos contacts. Destroyers carried 10 torpedoes in two quintupal mounts. Launching early would allow the torpedoes to run toward the enemy formation. Some might hit. More importantly, Japanese ships detecting incoming torpedoes would maneuver to avoid them, disrupting their formation.

Lee refused the request. He had a specific reason. He didn’t want American torpedoes and Japanese torpedoes running in the same water space. In darkness, with multiple ships maneuvering, nobody could be certain where all the torpedoes were. An American ship might maneuver to avoid Japanese torpedoes and run into American torpedoes instead.

Friendly fire from torpedoes was a real danger in night combat. Lee ordered the destroyers to engage with guns only and maintain their screening position. Hold fire until the enemy was close. Keep the formation between the Japanese and the battleships. Absorb the initial attacks. The destroyers understood their mission.

They were expendable. The battleships weren’t. The Japanese spotted the American destroyers first. Destroyer Iron Army leading the Japanese destroyer screen detected ships ahead at approximately 11,000 yards. The Japanese had no radar, but their optics were excellent, and their lookouts were rigorously trained for night combat.

Japanese destroyers carried powerful optical rangefinders and excellent binoculars. The lookouts had been dark, adapted for hours. They could see farther than most people would think possible. Ayanami’s commander, Lieutenant Commander Sato Tomokatsu, immediately identified the contacts as enemy warships and made his decision.

He would attack with torpedoes first, then illuminate with search lights and open fire. Iron Army launched a spread of type 93 torpedoes. The type 93 called Long Lance by the Americans was the best torpedo in the world. It was 24 ft long and weighed 2 tons. The warhead contained 1,000 lb of high explosive.

The torpedo was powered by oxygen enriched kerosene which produced no visible wake. American torpedoes left white trails of bubbles that could be seen from miles away. The long lance was nearly invisible. The torpedo ran at 48 knots with a range of 20 m at that speed. American torpedoes typically ran at 45 knots with a range of 6,000 yd.

The long lance could hit from three times farther away at higher speed. It was a devastating weapon that gave Japanese destroyers a huge advantage in night combat. Iron army launched eight torpedoes in a spread pattern. The torpedoes entered the water and accelerated to speed.

They would take about 8 minutes to reach the American formation at current ranges. Sarto then ordered his search light operators to illuminate the lead American destroyer. A powerful search light snapped on, its beam stabbing across the dark water. The light found Waler immediately. She was illuminated perfectly, silhouetted against the darkness.

Iron Army opened fire with her. 5-in guns at a range of 8,000 yd. Light cruiser Nagara following behind the destroyer screen also opened fire. Within seconds, multiple Japanese ships concentrated on the illuminated target. Walker was being hit before Fraser could fully react. Commander Fraser ordered hard left rudder to evade torpedoes and returned fire.

Walk’s 5-in guns engaged arami. Several hits were observed on the Japanese destroyer. Ayonami’s search light went out, knocked out by American shells. But more Japanese shells were hitting Walkie. Her forward superructure was struck repeatedly. Fires started on the bridge. The forward 5-in mount was knocked out by a direct hit.

Fraser launched all 10 torpedoes to clear his tubes and continued firing with his remaining guns. The situation was desperate. Walk was heavily engaged against multiple enemy ships. Fires were spreading. Casualties were mounting. At 23 26 hours, a shell penetrated Walk’s forward magazine. The magazine contained several tons of ammunition for the 5-in guns and smaller weapons.

The explosion was catastrophic. The entire forward section of the ship from the bow to the bridge disintegrated in a massive fireball. The blast killed everyone forward instantly. Walk broke in two. The forward section sank immediately. The aft section remained afloat for perhaps 30 seconds before capsizing and sinking.

Commander Fraser died instantly. Most of the crew died in the explosion or went down with the ship. 76 men were killed. Approximately 60 survivors went into the water wearing life jackets. They would spend hours in the darkness waiting for rescue. Preston was second in line about 600 yd behind Walk. Lieutenant Commander Max Storms saw Walker explode ahead.

He continued forward toward the enemy. Preston’s radar showed multiple Japanese ships. Storms ordered his guns to engage the nearest contacts. Preston’s 5-in battery opened fire at destroyer Ionami and light cruiser Nagara. Japanese destroyers Uranami and Shikinami returned fire. Preston was hit almost immediately. Multiple shells struck within seconds.

One hit destroyed the SG radar antenna. Another penetrated the after engine room. High-press steam lines ruptured. Superheated steam filled the compartment, killing everyone inside instantly. Preston lost power to her after guns and half her propulsion. More shells hit. The pattern was consistent with multiple ships firing at Preston simultaneously.

Her bridge was struck, killing several officers, including the executive officer. Communications were cut between the bridge and the rest of the ship. Fires spread amid ships where fuel oil tanks had been ruptured. The ship was dying. At 2330 hours, a type 93 torpedo slammed into Preston’s starboard side amid ships. The massive explosion broke the destroyer’s keel.

The ship’s back was literally broken. She began settling rapidly. Storms ordered abandoned ship. He stayed on the bridge helping men escape. Less than 30 seconds after the abandoned ship order, Preston rolled over to starboard and sank Bow first. 116 men died, including Captain Storms. About 90 men survived and went into the water.

Benham was third in line. Lieutenant Commander John Taylor saw both lead destroyers sinking ahead. Explosions lit up the darkness. Burning fuel oil spread on the water. Taylor ordered emergency turn to starboard to avoid collision with wreckage and survivors. As Benham turned, a type 93 torpedo struck her bow.

The torpedo hit at the water line about 30 ft back from the stem. The explosion was enormous. The entire forward section from the bow back to the bridge was blown off. The forward gun mounts simply disappeared. The bow structure vanished. anchor chains, cable lockers, forward crew birthing spaces, forward magazines, all gone. About 60 ft of the ship ceased to exist.

But the torpedo hit forward of the main watertight bulkhead. The bulkhead held. Water rushed in through the destroyed bow section, but stopped at the bulkhead. Benham’s stern section from the bridge aft remained intact and watertight. Taylor managed to stabilize the ship. The engines still worked.

Steering was functional using the rudder, but Benham could only make five knots with her bow gone. The water resistance was too great. She was out of the fight. Taylor withdrew south toward Guadal Canal, hoping to beach the ship for emergency repairs. Remarkably, Benham stayed afloat all day November 15th. She attempted to reach Guadal Canal, but couldn’t make headway. Finally, at 1938 hours, after nearly 20 hours a float with her bow missing, Benham was scuttled by gunfire from USS Gwyn. All crew members survived.

Nobody was killed by the torpedo hit. It was the only good news from the destroyer engagement. Gwyn was fourth and last in line. Lieutenant Commander John Fellows saw three to lead destroyers hit ahead. Explosions and fires indicated the destroyer screen was being overwhelmed.

Fellows ordered Gwyn to engage with all guns and prepare to maneuver independently. Gwyn’s 5-in battery fired at multiple Japanese targets. At 2332 hours, a Japanese shell hit Gwyn’s after engine room. The explosion killed several men in the engineering spaces and disabled one engine, but Gwyn remained operational on her remaining engine.

She could still make about 20 knots. Fellows continued engaging until Lee ordered the surviving destroyers to withdraw at 0045 hours. In 15 minutes, the American destroyer screen had been effectively destroyed. Two destroyers sunk with heavy loss of life. One crippled and withdrawing with her bow blown off, one damaged, but still operational.

The Japanese destroyer and cruiser screen had executed their night combat doctrine perfectly. They’d engaged aggressively with torpedoes and gunfire. They’d overwhelmed the American destroyers with concentrated fire. They’d broken through the screening force and cleared the way for Kirishima and the heavy cruisers to engage the American battleships.

This was exactly what Japanese destroyer doctrine called for. Destroy the screening units, then allow the capital ships to engage the enemy battle line. This was exactly the scenario Lee had feared but accepted as unavoidable. His destroyers couldn’t match Japanese destroyers in night combat.

The Japanese had better torpedoes, better training, better tactics, and more experience. But Lee had positioned his destroyers to absorb the initial attack and protect the battleships. The destroyers had done their job at terrible cost. Now it was up to Washington and South Dakota to complete the mission.

Everything depended on the battleships using their radar advantage before the Japanese found them. USS South Dakota had maneuvered independently when the destroyer action started. Captain Thomas Gatch was an aggressive officer who wanted to close with the enemy. He moved South Dakota ahead of Washington to engage. At 2338 hours, South Dakota’s SC air search radar picked up surface contacts at 18,000 yd.

The SC radar was less capable than the SG, but it could detect large ships at long range. Gatch ordered his main battery to prepare to engage. The gun crews loaded armor-piercing shells. The fire control team began tracking the contacts. South Dakota was preparing to fire when disaster struck. South Dakota’s electrical system failed.

The failure was caused by human error compounded by poor design. During the afternoon, electrical repairs were being conducted. A circuit breaker tripped. The chief engineer manually reset the breaker while it was still under load. Navy regulations prohibited this because it could cause cascading failures. That’s exactly what happened. Resetting the breaker under load caused it to trip again.

When it tripped, caused other breakers in the circuit to trip. The failures cascaded through the electrical distribution system. Within seconds, the entire ship lost power. Everything went dark. Radar screens went black. Gun directors lost power. Fire control computers shut down. Communications went dead. Ventilation stopped. Even emergency lighting failed in some compartments.

Damage control teams worked frantically in complete darkness trying to restore power. They had flashlights and battle lanterns, but resetting breakers and troubleshooting electrical systems in darkness was nearly impossible. The engineering crew managed to restore partial power within about 5 minutes, but the damage was done.

South Dakota’s combat capability was shattered at the worst possible moment. Without radar, South Dakota was blind. Her lookouts could see the burning American destroyers a stern, but they couldn’t see Japanese ships ahead. Without fire control power, her main battery couldn’t be aimed.

Without communications, Captain Gat couldn’t coordinate with Lee or with his own gun crews. South Dakota continued moving forward on momentum and manual steering. She was heading directly toward the Japanese force without sensors or working weapons. It was a nightmare scenario. At 0001 hours, power was partially restored. Some radar systems came back online. Fire control systems rebooted, but the ship had drifted during the power failure.

South Dakota had sailed to within 5,000 yds of the Japanese force, far closer than Gat intended. Japanese cruiser Atargo detected the American battleship at close range and illuminated her with a search light. The powerful beam found South Dakota immediately. She was perfectly silhouetted by the burning American destroyers behind her, backlit by the fires.

Every Japanese ship in range opened fire. Kirishima fired her main battery of 14-in guns at a range of 5,500 yds. This was pointblank range for battleship guns. The Japanese shells crossed the distance in about 8 seconds. Heavy cruisers Atarago and Takao fired their 8-in guns. Light cruiser Sendai fired 6-in guns.

Multiple destroyers fired 5-in guns. South Dakota was hit by shells of every caliber. The ship was struck at least 27 times in 3 minutes. Most hits came from 8 in, 6 in, and 5-in guns. These shells couldn’t penetrate South Dakota’s armored belt or turret faces, but they destroyed everything topside. The forward main battery director took a direct hit from a 14-in shell.

The shell didn’t penetrate the armored director, but the impact destroyed the optics and knocked out the crew inside. Men were killed by concussion even though the shell didn’t explode. The radar antennas were shattered by shell fragments. Gun mounts were hit. The number three turret took an 8-in shell hit on the barbette, but the shell didn’t penetrate.

Fires started in multiple locations. The superructure was riddled with holes. 39 men were killed. 59 were wounded. The ship looked like she’d been through a scrap metal shredder. South Dakota’s armor did its job. None of the hits penetrated vital spaces. The engines kept running. The ship maintained speed. The main battery turrets could still fire in local control without the directors.

But South Dakota was effectively out of the fight. She couldn’t use radar. She couldn’t use centralized fire control. She was partially blind and heavily damaged. Captain Gat ordered an emergency turn to Starboard to escape the Japanese formation. South Dakota turned hard and disappeared back into darkness, heading south away from the enemy. Her sacrifice had achieved one critical result.

She’d drawn every Japanese ship’s attention. While South Dakota was being pounded, USS Washington was invisible in the darkness, tracking Japanese ships on radar, preparing to fire. The Japanese thought they’d won. In less than 20 minutes, they’d destroyed or driven off every American ship they’d engaged. Four destroyers sunk or crippled.

One battleship damaged and retreating. Admiral Condo on cruiser Atargo congratulated his force on their success. He ordered the formation to reform and proceed north to bombard Henderson Field. The primary mission could now proceed unopposed. Japanese commanders didn’t know that USS Washington existed.

Every Japanese ship had been focused on the destroyers and South Dakota. Washington had stayed back in darkness, tracking everything on radar, waiting for the perfect moment. In Washington’s plotting rooms and directors, the radar operators and fire control teams had complete information.

The SG radar showed all Japanese ship positions clearly. The returns were distinct and easy to track. The Mark III fire control radar on the forward director was locked onto the largest contact, tracking it continuously. The radar measured range every few seconds. The Mark 8 range keeper computed the firing solution continuously updating as both ships moved.

Target bearing, target range, target course and speed estimated from radar plot tracking. Own ship course and speed. Wind, all the variables fed into the computer. The solution was ready. All turrets were loaded with armor-piercing shells. The guns were trained on target and elevated to the calculated angle. Everything was ready. Washington just needed permission to fire.

Admiral Lee stood on the bridge with Captain Davis. Lee wore a headset connected to the radar plot and fire control circuits. He could hear everything the operators were saying. He watched the radar plot display showing the tactical situation. He could see the Japanese battleship clearly on the screen. Range 8,400 yd. The target was moving slowly northwest heading toward Henderson Field.

The Japanese ship had no idea Washington existed. Lee had the perfect setup. His ship was invisible. His target was fully illuminated on radar. His guns were ready. This was the moment everything had been building toward. Lee looked at Captain Davis and said simply, “Stand by Glenn. Here they come.” Davis gave the order that changed everything.

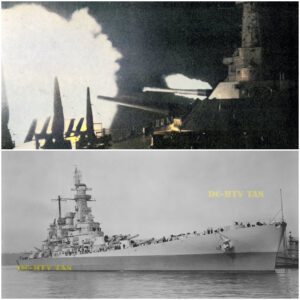

Main battery commence firing at 0100 hours. Exactly 1:00 in the morning of November 15th, 1942, USS Washington opened fire. All nine 16-in guns in three triple turrets fired together in a single massive salvo. The sound was indescribable. The blast pressure was so intense it could rupture eard drums. The muzzle flash lit up the entire sky like lightning.

The ship shuddered and healed slightly to starboard from the recoil force. Nine shells weighing 2,700 lb each flew toward Kiroshima at 2600 ft pers. That’s about 1,800 mph. The shells were in the air for approximately 20 seconds while they covered 8,400 yd. Each shell was ozer, an armor-piercing projectile. The shell body was forged steel.

The nose was hardened to penetrate armor. Inside was about 40 lb of high explosive with a base detonating fuse. The fuse was designed to explode after penetration, not on impact. The shell would punch through armor plate, travel into the ship, then explode inside where it would cause maximum damage.

The ballistic trajectory was carefully calculated. The shells left Washington’s guns at 45° elevation. They arked upward to a peak height of about 20,000 ft, then descended at a steep angle toward the target. The steep angle meant the shells would penetrate Kirishima’s deck armor, which was thinner than her side armor. The Japanese on Kirishima had no warning. They couldn’t see Washington.

Their lookouts were focused forward toward Henderson Field. The first indication they had of danger was when nine shells arrived. The first salvo hit Kirishima’s superructure and for deck. Two shells struck the forward superructure. Both exploded. The bridge area was smashed. The rangefinder on top of the bridge tower was destroyed.

Fire control equipment was wrecked. Communications lines were cut. Electrical cables were severed. Fires started immediately as fuel lines and hydraulic lines ruptured. Hiroshima’s captain, Sanji Iwabuchi, was on the bridge when the shells hit. He was knocked down by the concussion but survived. Most of the bridge crew was killed or wounded.

Iwabuchi got to his feet and tried to assess the damage. Smoke filled the bridge. Electrical power flickered. Communications to other parts of the ship were cut. He couldn’t determine where the firing was coming from. He ordered return fire, but wasn’t sure what target to fire at. The gun crews could see muzzle flashes off to the south, but the range was unknown.

Washington’s gun crews were already reloading. The hydraulic rammers pushed new shells into the breaches. Each shell was mechanically lifted from the magazine below, brought up through the turret structure, and loaded. Powder bags followed. Each gun required six powder bags. The breaches closed and locked automatically. The entire loading cycle took about 30 seconds.

The second salvo was ready to fire. The fire control solution had been updated based on the latest radar ranging. Washington fired again at 01030. This salvo hit Kiroshima forward and amid ships. One shell penetrated the armored deck near turret number one, the forwardmost turret.

The shell went through the deck and exploded in a compartment just above the forward magazines. The explosion caused fires and flooding. Damage control parties immediately flooded the magazines to prevent detonation. This saved the ship from catastrophic explosion, but it also disabled turret number one. With the magazine flooded, the turret couldn’t be supplied with ammunition.

Another shell hit the forward superructure and destroyed the backup fire control position. A third shell hit the formast and brought down the main fire control director. The director fell onto the deck, crushing men below. Kirishima’s main battery fire control was now effectively destroyed. Kirroshima tried desperately to return fire.

Her aft turrets, turrets three and four, were still operational. The local gun captains in those turrets could see muzzle flashes from Washington’s guns. They trained their turrets toward the flashes and fired. Kirishima got off several salvos of 14-in shells at Washington, but without working fire control systems and without radar, the Japanese gunners had no accurate range.

They estimated Washington was about 10,000 yd away based on the brightness of the muzzle flashes. They were close. Washington was actually at 8,600 yd, but close wasn’t good enough. The Japanese shells flew toward where Kiroshima’s gunners thought Washington was.

The shells passed over Washington’s masts, missing by perhaps 200 ft. One witness on Washington said, “They must have been mighty close, but close doesn’t count.” Washington’s third salvo fired at 0101. All nine guns again. This salvo concentrated amid ships. Three shells hit Kiroshima’s machinery spaces. One shell penetrated the side armor and exploded in the forward engine room.

The explosion was devastating. Boilers were ruptured. Steam lines burst. Turbines were damaged. The engineering crew was killed or driven out by superheated steam. Another shell hit near the after engine room with similar results. Kiroshima started losing power. Her speed dropped from 20 knots to 15 then to 10. The ship was dying. The fourth salvo fired at 010130.

Two more penetrating hits amid ships and aft. One shell went through the deck and exploded in a machinery space near the steering gear. The hydraulic lines that powered the steering were destroyed. Kirishima lost steering control. The ship began turning slowly in a poin circle. Unable to control her direction.

Another shell destroyed the hydraulic pumps that powered the training mechanism for turrets three and four. Kirishima’s aft main battery was now useless. The turrets couldn’t be trained or elevated. The ship had lost all main battery capability. The fire control teams in Washington’s plotting rooms watched the radar return.

They could see the target was slowing and appeared to be turning. Something was clearly wrong with the Japanese ship. The fire control solution was updated for the changing target motion. The fifth salvo fired at 0102. Two more hits. One shell exploded in crew birthing spaces on the port side. Over a 100 men were killed instantly.

The other shell hit the after superructure and destroyed the emergency steering position. Fires were now burning from bow to stern. Kirishima was completely ablaze. The sixth salvo fired at 010230. One massive hit near the water line on the starboard side. The topped shell penetrated the side armor and exploded in a compartment already damaged by earlier hits. Water poured in through the hole.

The flooding was uncontrollable. Kiroshima developed a list to starboard that grew steadily worse. The pumps couldn’t keep up with the flooding. More compartments were being deliberately flooded to prevent magazine explosions. The weight of water was dragging the ship down. In 7 minutes, Washington had fired 7516in shells in nine salvos.

At least nine shells hit Kiroshima in vital areas with devastating effect. Modern analysis of the wreck using sonar surveys suggests 17 to 21 total hits, many below the water line where they couldn’t be observed during the battle. Washington’s 5-in secondary battery also fired throughout the engagement. The 5-in guns engaged multiple targets, including cruisers and destroyers.

Approximately 1075-in shells were fired. 17 to 20 hit Kirroima. These smaller shells couldn’t penetrate armor, but they destroyed everything above deck. Gun mounts were knocked out. Search lights were shattered. Boats and davits were destroyed. The superructure was riddled with holes. Men caught in the open were killed by fragments.

At 0107, 7 minutes after opening fire, Lee ordered ceasefire. Kiriroshima was clearly finished. She was dead in the water, burning from multiple fires, listing heavily to starboard, unable to steer or fight. There was no point wasting ammunition on a sinking ship. Washington had other concerns. Japanese destroyers were launching torpedoes. Lee had to maneuver to avoid them.

Type 93 torpedoes were already in the water. Every Japanese destroyer had launched their full load out when they detected Washington’s muzzle flashes. Dozens of torpedoes were running toward Washington’s last known position. The torpedoes ran at 48 knots with almost no visible wake. They were nearly impossible to see at Braum night.

Lee ordered emergency maneuvers. Hard left rudder, increase speed to 25 knots, then hard right rudder, then left again. Washington zigzagged through Iron Bottom Sound at high speed. Lookouts on Washington spotted torpedo wakes crossing ahead of the ship. More wakes past a stern.

Washington was surrounded by torpedoes running in multiple directions, but Lee’s constant maneuvering kept the ship clear. The Japanese had aimed at where Washington should have been based on her gun flashes. They couldn’t adjust aim without radar. Lee’s zigzag pattern meant Washington was never where the torpedoes expected her to be. It was a close call. Several torpedoes passed within a 100 yards, but none hit.

Washington maneuvered through the torpedo water and emerged without damage. At 0300 hours, Lee ordered Task Force 64 to withdraw south. The mission was accomplished. Kiroshima was sinking. The Japanese bombardment had been stopped. Henderson Field was safe. There was no reason to stay and risk further damage.

Lee formed up with the damaged South Dakota and surviving destroyers and headed back toward Guadal Canal. Behind Washington, Kiroshima was in her death throws. Japanese destroyers Asagumo and Teruzuki came alongside to evacuate survivors. Captain Iwabuchi and most of the crew abandoned ship. Over 2,000 men were rescued.

Light cruiser Nagara attempted to take Kiroshima in tow, but the damage was too severe. The battleship was flooding in multiple compartments. The list to starboard reached 18° and kept increasing. The ship was settling by the bow. At 0325 hours, 3 hours and 25 minutes after Washington’s first salvo, Kiroshima capsized and sank. 212 men went down with her.

The ship sank about 7 and 12 mi northwest of Tsavo Island in water over 2,000 ft deep. USS Washington had accomplished what no other American battleship would achieve during World War II. She had defeated an enemy battleship in a one-on-one surface engagement. More importantly, she had proven that radar could dominate naval combat.

Washington had tracked Kirishima on radar for over 20 minutes while remaining invisible to Japanese lookouts. Washington had fired nine salvos of calculated fire without visual spotting and achieved devastating accuracy. The engagement demonstrated that electronics had become more important than eyesight in naval warfare, but understanding the full significance of the victory took time. The official Navy action reports focused on Admiral Lee’s tactical skill and crew training.

Captain Davis wrote in his report that radar was critical, but many readers interpreted this as radar being helpful rather than decisive. Senior officers still thought of naval combat in terms of visual range gunfire and torpedo attacks.

The idea that ships could fight entirely by electronics was difficult for men trained in traditional methods to fully accept. Captain Davis understood what had happened. In his action report, he made a statement that would prove prophetic. Radar has forced the captain or officer in tactical command to base a greater part of his actions on what he is told rather than what he can see. This was revolutionary.

For centuries, naval commanders had operated by looking at the enemy and making decisions based on visual information. They could see the enemy formation. They could see where shells were landing. They could see damage on enemy ships.

Now they would sit inside ships and make decisions based on electronic displays showing dots and numbers. The nature of naval command had fundamentally changed. But changing command required more than technology. It required new doctrine, new training, and new organizational structures. In November 1942, these didn’t exist. They were created in the months after Guadal Canal based on lessons from Washington’s victory.

The Navy began developing formal procedures for organizing radar information. Before Guadal Canal, radar operators worked in scattered locations around ships with no standardized procedures. After Guadal Canal, the Navy began centralizing radar displays, plotting tables, and communication systems into dedicated spaces.

By January 1943, the Navy formally designated these spaces as combat information centers. Trained personnel staffed the CIC to maintain situation awareness for the commanding officer. The CIC concept was developed directly from lessons learned at Guadal Canal.

If Washington had possessed a fully developed CIC in November 1942, the battle might have been even more one-sided. As it was, Washington’s crews improvised effective procedures that became the foundation for future CIC doctrine. The Navy also created formal training programs for radar operators and CIC personnel. Before Guadal Canal, radar training was minimal and inconsistent.

After Guadal Canal, the Navy established schools teaching operators how to interpret radar returns, track multiple targets, maintain plots, and communicate effectively with bridge officers and weapons stations. Officers received training in how to command using radar data as their primary information source. The curriculum emphasized that radar wasn’t a backup to visual systems.

It was the primary sensor, especially at night. Tactical doctrine changed fundamentally. Before Guadal Canal, formations were designed around visual signaling and optical fire control. Ships operated in columns or lines where each ship could see the next. Flag signals controlled maneuvers.

After Guadal Canal, formations were designed around radar coverage. Ships with superior radar systems were positioned where they could track the most contacts. Multiple ships coordinated fire using radar data shared by radio.

Task force commanders were required to use ships with the best radar as flagships regardless of which ship was most powerful. This represented a complete inversion of traditional doctrine. The impact became clear within a year. In November 1942, American forces were barely holding their own in night battles against the Japanese. By November 1943, Japanese ships avoided night engagements unless they had overwhelming numerical superiority.

Three night surface actions in the second half of 1943 demonstrated American dominance. At Vela Gulf in August, American destroyers using radar detected Japanese destroyers at long range maneuvered into position and destroyed three Japanese destroyers with radar directed torpedo attacks before the Japanese knew American ships were present.

At Empress Augusta Bay in November, American cruisers and destroyers defeated a Japanese force using radar directed gunfire at Cape St. George. In November, American destroyers intercepted and destroyed three Japanese destroyers in a night action entirely controlled by radar. American forces took minimal damage in all three engagements. Night combat had become an American advantage.

The Japanese tried desperately to adapt. They examined wreckage from sunken American ships and found radar equipment. They understood the principle of using radio waves to detect ships, but they were years behind in development. Japanese radar in 1943 was roughly equivalent to American radar in 1941.

The equipment was less reliable, had shorter range, and lacked the sophisticated displays that American systems featured. By the time Japan developed working surface search radar comparable to the American SG, it was 1945 and the war was nearly over. Even then, Japanese radar was fitted to only a handful of ships. Japanese commanders also struggled with the psychological impact of fighting an enemy they couldn’t see.

For 2 years, Japanese destroyer and cruiser captains had dominated night battles through superior training and aggressive tactics. They developed confidence that bordered on arrogance. Japanese night fighting doctrine was taught throughout the Navy as the gold standard.

Now they were being beaten consistently by ships they couldn’t see, firing from ranges where visual spotting was impossible. The confidence built over 20 years of training evaporated. Captains who had been aggressive became cautious. Units that had pressed attacks began withdrawing when radar equipped American ships appeared. The psychological shift was as important as the tactical shift.

Several experienced Japanese commanders were killed in late 1942 and throughout 1943 trying tactics that had worked perfectly before Guadal Canal. They closed to short range for torpedo attacks and were destroyed by radar directed gunfire before they could launch.

They tried to use search lights to illuminate targets and were hit by ships firing from beyond search light range. They attempted to evade by maneuvering at high speed and were tracked continuously by radar. The fundamental problem was that they were fighting an enemy using a technology they couldn’t detect and couldn’t counter.

It’s impossible to develop effective tactics against a capability you don’t understand. Admiral Lee understood this completely. After the battle, he wrote a letter to Admiral Holy that demonstrated remarkable insight and humility. Lee stated that American superiority at Guadal Canal was due almost entirely to radar. He wrote explicitly, “We realized then, and it should not be forgotten now, that our entire superiority was due almost entirely to our possession of radar.

Certainly, we have no edge on the Japs in experience, skill, training, or performance of personnel.” Lee was absolutely correct. Japanese crews were superbly trained. Japanese officers had more combat experience. Japanese doctrine was more developed. Japanese equipment, especially torpedoes, was in many ways superior. The only American advantage was radar, and that one advantage was decisive.

Lee never received full public credit for this insight during his lifetime. He was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions at Guadal Canal. The citation praised his leadership and tactical skill. He was promoted to vice admiral in 1944 and given command of all fast battleships in the Pacific Fleet.

As commander battleships Pacific Fleet, he participated in every major campaign from 1943 through 1945. But most histories of Guadal Canal focused on the desperate surface actions of November 12th and 13th, where Admirals Callahan and Scott died leading close-range attacks against overwhelming odds. Those actions had clear heroes and dramatic sacrifice.

Lee’s victory on November 14th and 15th received less attention because it appeared too easy. Washington suffered zero casualties. She wasn’t even scratched. It didn’t look like the same kind of heroic struggle. But Lee’s victory was actually harder than it appeared. The decision to trust Radar completely was radical in November 1942. Most admirals considered radar interesting but unproven.

They’d been trained in an era when visual spotting and optical instruments were the only reliable methods. Radar challenged everything they’d learned. Lee bet his entire force on technology that others viewed skeptically. If the radar had failed, if the data had been wrong, if the fire control solutions had been off by even a few degrees, Washington would have sailed blind into a superior Japanese force and been destroyed.

The consequences of failure would have been catastrophic. Henderson Field would have been destroyed. Guadal Canal would have been lost. The entire Pacific offensive would have stalled. Lee’s genius was understanding that radar was more reliable than human vision in darkness and then having the courage to act on that understanding.

That understanding came from years of study. Lee had spent three years as a director of fleet training studying gunnery systems. He’d worked with engineers developing radar equipment. He’d read British reports on radar use in the Atlantic. He’d attended technical briefings. He’d trained his crews extensively. He knew the capabilities and limitations of radar better than any flag officer in the Navy.

When the moment came, he trusted his knowledge over conventional wisdom. That kind of leadership is rare in any era. USS Washington remained in service for the duration of the war. She participated in nearly every major Pacific campaign from 1943 onward. She screened fast carriers at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, where American carrier aircraft destroyed hundreds of Japanese planes in what became known as the Great Mariana’s Turkey Shoot.

She was present at the Battle of Lee Gulf in October 1944. Though she didn’t engage in surface combat, she bombarded Japanese positions during the assaults on Ewo Jima in February 1945 and Okinawa in April and May 1945. She was present at the Japanese surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay on September 2nd, 1945. After the war, Washington was used to transport soldiers home as part of Operation Magic Carpet.

She made two trips across the Atlantic in November and December 1945, carrying over 1,600 soldiers from Europe to the United States. She was decommissioned on June 27th, 1947 at the New York Navy Yard and placed in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. She remained in reserve for 13 years while the Navy decided what to do with World War II era battleships.

By 1960, it was clear that battleships had no place in modern naval warfare. Aircraft carriers and guided missiles had made gunarmed surface ships obsolete except for shore bombardment. Washington was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on June 1st, 1960. She was sold for scrap on May 24th, 1961 to Lipet Division of Lura Brothers Company in New York.

The ship was towed to the scrapyard and systematically dismantled. Her 16-in guns were cut apart with torches. Her armor plates were removed and melted down. Her superructure was dismantled piece by piece. By the end of 1961, USS Washington had ceased to exist except as scrap metal. A few artifacts were preserved before scrapping. The ship’s bell was saved. The ship’s wheel was preserved.

Some commemorative plaques and deck fittings survived. These items are held in various naval museums and archives. Captain Glenn Benson Davis remained in the Navy after the war. He was promoted to Rear Admiral and commanded battleship division 8 during the Mariana’s campaign in 1944. He continued advancing and became vice admiral.

He served as commandant of the Washington Navy Yard from 1950 to 1952 and as commandant of the sixth naval district in Charleston, South Carolina. He retired from the Navy in 1954 after 43 years of service. Davis died on September 9th, 1984 in Bethesda, Maryland at age 92. His contributions to radar doctrine and his partnership with Admiral Lee were recognized by naval historians, but he remained modest about his role.

In interviews late in his life, Davis consistently credited Lee’s vision and the crews training for Washington’s success. Admiral Willis Augustus Lee never saw the end of the war. On August 25th, 1945, 10 days after Japan surrendered, Lee suffered a massive heart attack. He was being fed in a motor launch across Casco Bay from his shore headquarters to his flagship USS Wyoming.

Anchored in the harbor of Portland, Maine, Lee collapsed in the boat and died before reaching Wyoming. He was 57 years old. The cause was acute coronary thrombosis, essentially a massive heart attack. Three years of constant stress commanding battleship forces in combat had taken their toll. Lee had been in combat operations almost continuously from August 1942 through August 1945.

He’d commanded during some of the most intense naval battles of the war. The physical and mental strain had been enormous. Lee was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. His grave is marked with a simple white marble headstone.

The inscription lists his name, rank of vice admiral, and dates of birth and death. It mentions his seven Olympic medals. It doesn’t mention Guadal Canal. It doesn’t mention that he proved radar could revolutionize warfare. It doesn’t mention that his understanding of technology gave the United States a decisive advantage in the Pacific War. Lee would probably have preferred it that way.

He was never interested in glory or recognition. He was interested in solving problems and winning battles. The engagement between USS Washington and Kirishima lasted 7 minutes from first salvo to cease fire. In that time, Washington fired 75 rounds of 16-in ammunition and 107 rounds of 5-in ammunition. The 16-in shells alone weighed over 100 tons.

The propellant charges for those shells weighed another 70 tons. The total ammunition expenditure was approximately $150,000 in 1942 prices, equivalent to about $2.5 million today. The ammunition cost was insignificant compared to the strategic value of the victory. Washington’s victory saved Henderson Field from bombardment.

Japanese forces never again seriously attempted to destroy the airfield with naval gunfire. Without Henderson Field, American forces on Guadal Canal couldn’t maintain air superiority. Without air superiority, supplying and reinforcing the Marines would have been nearly impossible. Japanese aircraft and ships would have dominated the pose. The waters around Guadal Canal.

The campaign might have been lost. If Guadal Canal had been lost, the entire American offensive strategy in the Pacific would have been called into question. The island hopping campaign toward Japan depended on establishing forward bases. If the first major attempt at establishing a base failed, it would have taken months or years to rebuild the forces and try again.

But the greater long-term impact was proving that radar could dominate surface naval combat. Before November 15th, 1942, radar was viewed as experimental technology that might be useful in some circumstances. After that night, radar became recognized as the foundation of modern naval warfare. Every navy in the world began intensive radar development programs.

Ships were retrofitted with radar. New ships were designed from the keel up with radar as a primary sensor. Tactics and doctrine were rewritten around radar capabilities. The era of visual range combat ended. The era of electronic warfare began. The transformation happened remarkably quickly. In January 1942, fewer than 100 American warships had any kind of radar.

By January 1945, virtually every American warship had multiple radar systems. Fire control radar, air search radar, surface search radar, identification systems. Ships carried half a dozen different radar systems, each optimized for different functions. The electronic equipment became as important as the guns.

Some historians argue that radar was the single most important technology of World War II naval warfare, more important than aircraft carriers or submarines or any weapon system. The lesson from USS Washington’s victory isn’t ultimately about technology. It’s about leadership willing to trust new technology when conventional wisdom says otherwise.

Admiral Lee had decades of experience in an era when battleships fought with visual spotting and optical rangefinders. Every instinct developed through 34 years of naval service should have told him to be cautious with experimental electronics. His career had been built on mastering traditional gunnery. He was probably the best gun expert in the Navy.

He could have relied on traditional methods because that’s what he knew best. Instead, Lee abandoned those methods completely. He committed entirely to radar because he’d done the intellectual work to understand it. He’d studied the engineering principles. He’d examined combat reports. He’d trained his crews extensively. He tested the systems in exercises. He knew radar would work because he’d verified it through study and practice.

When the moment came in pitch darkness with destroyers sinking and another battleship crippled and a superior Japanese force approaching, Lee trusted his radar operators and fire control teams to do something unprecedented. He ordered Washington to fire at a target nobody could see using data from electronics that most officers didn’t fully trust.

The crews didn’t let him down. The radar tracked perfectly. The fire control computer calculated accurately. The guns fired precisely. Nine salvos in 7 minutes destroyed a Japanese battleship. Zero American casualties. The victory validated everything Lee had believed about radar. It proved that electronics could be more reliable than human senses.

It demonstrated that properly integrated technology could overcome numerical inferiority and tactical disadvantage. Most importantly, it showed that innovation succeeds when leaders understand new capabilities deeply enough to trust them completely. That kind of leadership remains rare. Most commanders follow established procedures. They trust proven methods.

They avoid risk by doing what has always been done. Innovation requires doing something that hasn’t been proven in combat. It requires accepting risk that others won’t accept. It requires trusting technology or tactics that haven’t been validated by experience. Admiral Lee did all of these things. He organized his ship around unproven technology.

He trained his crew to fight in ways no navy had fought before. He committed his entire force to a battle plan that depended on radar working perfectly and he succeeded. The result changed naval warfare forever. Night combat, which had been a Japanese advantage for 2 years, became an American advantage almost overnight. The technology that Admiral Lee trusted in November 1942, became the foundation for every navy in the world.

The radar displays and fire control computers that seemed revolutionary in 1942 evolved into the modern combat systems that control warships today. The lessons Lee demonstrated that electronics can provide better information than human senses and that technology properly used can overcome superior numbers remain relevant 80 years later.