Why Rommel Changed His Mind About American Soldiers After Kasserine Pass….

The M3 halftracks with 75 mm guns were vulnerable in direct combat. They had thin armor. A German shell would penetrate easily. But positioned forward in concealed positions, they could engage German tanks at first contact, disrupt German formations, force the Germans to deploy prematurely.

Then the tank destroyers could withdraw to secondary positions while the hidden Shermans engaged. He positioned his artillery in depth with pre-registered fire zones covering every likely avenue of approach. The artillery included 11 batteries totaling over 60 guns. Most were 105 mm howitzers, standard American Divisional artillery. They had good range, good accuracy, good hitting power against both armored and soft targets.

Properly coordinated, they could deliver devastating firepower. Robinet worked with his artillery commander to establish pre-registered concentrations. They identified locations where German forces would likely assemble, approach routes they would probably use, positions where they might establish support weapons.

Each location received a concentration number. When forward observers called for fire on a specific concentration, every battery knew exactly where to aim. The shells would arrive quickly, accurately, in volume. He positioned his infantry on the flanks with clear fields of fire. The infantry came from the first infantry division, Terry Allen’s command. They were experienced soldiers.

They had fought in North Africa for 3 months. They knew how to dig foxholes, establish firing positions, coordinate with supporting arms. Robinet placed them where they could cover the tank positions, protect the artillery from infiltration, seal off the flanks against German attempts to envelop the defense. Most importantly, he coordinated everything. He held a commander conference on the evening of February 20th.

Every battalion commander, every company commander attended. He showed them a map of the defensive position. He explained how each unit fit into the overall plan. He showed the tank commanders where the tank destroyers would be. He showed the infantry commanders where the tanks would be.

He showed everyone where the artillery observers would be positioned and how to call for fire. He established communication procedures. Every unit had radio contact with every other unit. If the praise Germans attacked anywhere, everyone would know immediately. If one unit needed support, help could arrive quickly.

If artillery was needed, observers could call it in within minutes. The entire defensive position functioned as a single integrated system. Robinet worked through the night of February 20th. His units were exhausted. They had been retreating for 6 days. They had watched other units get destroyed. They had low confidence.

He walked among them, talked to platoon leaders and company commanders, explained the defensive plan, showed them how the position would work. He told them the Germans would come, probably at dawn, probably with tanks leading. He told them to hold their positions, trust the plan, fight as a team. At 0450 on February 21st, German reconnaissance elements probed the American position.

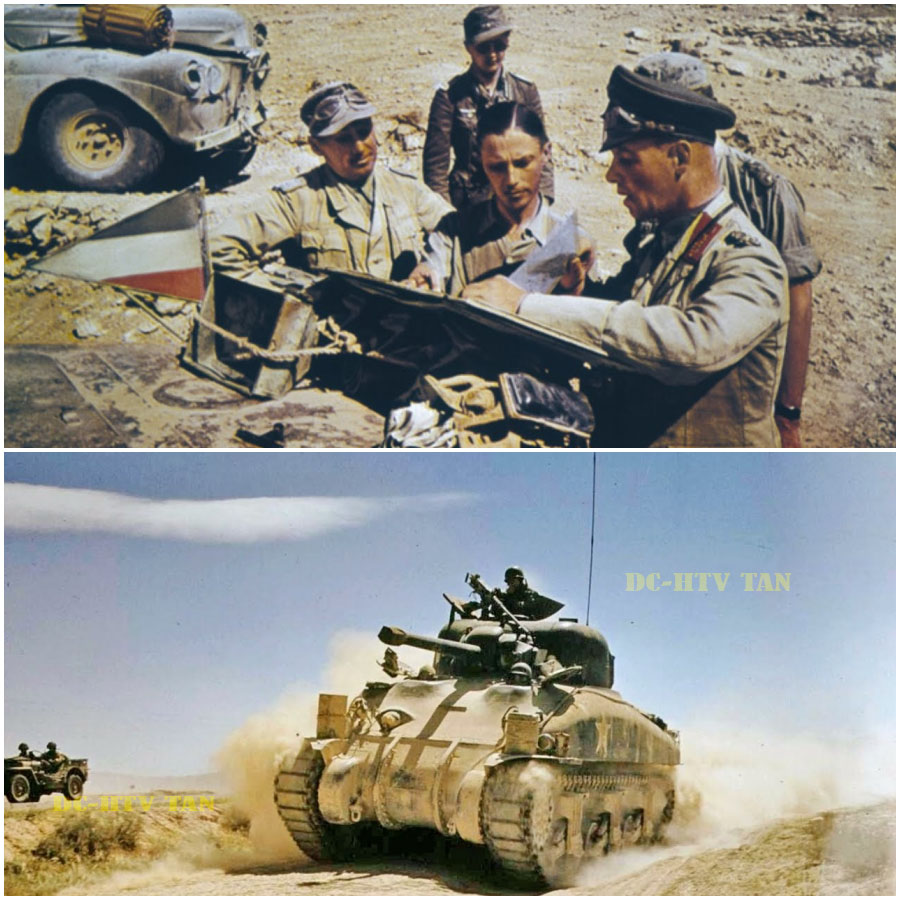

They reported back to RML that Americans were dug in along the valley in significant strength. RML decided to attack anyway. He had momentum. He had veteran troops. He believed the Americans would break like they had broken everywhere else. He was wrong. The German attack came at 1,400 hours on February 21st. 40 Panzas from the 10th Panza Division advanced up the valley floor with Italian Bersalei infantry and trucks behind them.

They expected to find disorganized Americans retreating in panic like every other engagement. Instead, they found a coordinated defensive position. American tank destroyers engaged from the forward line at 1500 yd. German tanks took hits, stopped, some burned. The panzas returned fire, knocked out several tank destroyers, kept advancing.

The tank destroyers fell back to secondary positions. Then the hidden Shermans opened fire from hull down positions in the Wadis. The Germans had not seen them. Suddenly they were taking fire from three directions. More tanks hit. More vehicles stopped. The Italian trucks carrying infantry tried to maneuver off the road. American artillery started falling.

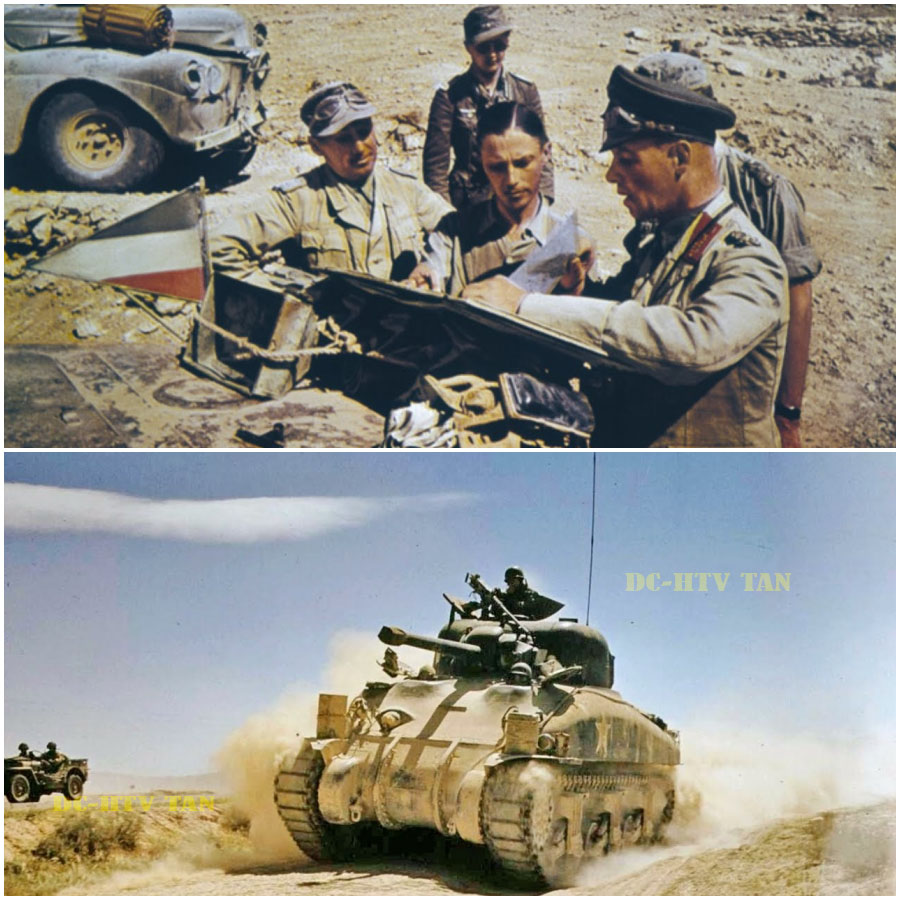

Pre-registered fire. Forward observers had called in concentrations. Shells landed among the trucks, destroyed them, killed infantry. The German attack stalled. Raml came forward personally to assess the situation. He could see American positions clearly now. They were not retreating. They were not panicking.

They were fighting from prepared positions with coordinated fire. His casualties were mounting. His fuel situation was critical. His ammunition was running low. He ordered another attack the next morning, February 22nd. Same axis, more force. Bring up everything available. breakthrough to Tobessa. The attack on February 22nd hit at 11:25 hours after delays caused by fog.

German tanks and Italian infantry pushed up the valley again. Again they met coordinated American resistance, tank destroyers, tanks in defilade, artillery fire, infantry with anti-tank weapons. The Germans made some progress, reached within 2 mi of the American artillery positions. Then American artillery opened up with mass fire.

11 batteries, 132 guns, all firing on pre-registered coordinates. The valley floor became a killing zone. German tanks took direct hits. Infantry in the open were cut down by shrapnel. Italian bezelieri units were decimated. Two battalions were effectively destroyed in 30 minutes of sustained bombardment. German forward momentum stopped. RML watched from his command post. He could see his attack falling apart. He could see casualties mounting.

He received reports that Montgomery’s 8th Army had reached the Marath line to the south, threatening his rear. He received reports that Allied reinforcements were arriving hourly at the passes. At 1600 hours on February 22nd, RML made his decision. He ordered a withdrawal. All units pull back through Casarine Pass. returned to starting positions. The offensive was over.

The Germans withdrew through February 23rd and 24th. American and British forces reoccupied Casarine Pass on February 25th. The battle was finished. American casualties totaled 6,600 men killed, wounded, or captured. They lost 183 tanks, 104 halftracks, 208 artillery pieces, 512 vehicles.

It was the worst American defeat in North Africa. But it was not the defeat RML expected. In his journal after the battle, he wrote something that surprised his staff. The tactical conduct of the American defense had been first class. The Americans had recovered quickly after the first shock and had succeeded in damning up the German advance by grouping their reserves to defend the passes.

They had positioned their artillery skillfully. They had employed combined arms effectively once they established proper defensive positions. This was not the assessment of an easy enemy. This was respect. What RML saw at the end of Casarine Pass changed his opinion of American forces fundamentally. The early battles at City Build and Spatler had shown him poorly coordinated American attacks and disorganized withdrawals.

But the defensive stand east of Tbessa, the artillery fire on February 21st and 22nd, the coordinated combined arms defense, that showed him something different, that showed him Americans could learn fast, that showed him Americans could adapt, that showed him Americans properly led and properly positioned could fight. Other German commanders missed this. They saw the first three days, the chaos, the retreats, the captured equipment.

They concluded Americans were weak. That conclusion would cost them dearly later. Field marshal Albert Kessler, Raml’s superior, believed the Casarine victory proved German forces could defeat Americans easily. He advocated for continued offensive operations in Tunisia. Most German staff officers agreed with Kessle Ring.

They looked at the statistics. Over 6,000 American casualties, nearly 200 tanks destroyed, thousands of prisoners captured. They saw overwhelming German victory. Raml saw the whole battle. He saw the first three days. He also saw the last two. He saw how quickly Americans stabilized.

He saw how effectively they used artillery once they established proper fire direction. He saw how well they fought from prepared positions with clear fields of fire and coordinated support. Most importantly, he saw the speed of adaptation from chaos at city bus on February 14th to effective defense at Tbessa on February 21st, 7 days.

That speed of learning was unprecedented in RML’s experience. The British had taken months to adapt after early defeats in North Africa. The French had never adapted after their defeat in 1940. The Italians had struggled with adaptation throughout the war, but the Americans had learned critical lessons in one week of combat.

That worried RML more than any tactical victory could satisfy him. RML saw the whole battle. He saw the first three days. He also saw the last two. He saw how quickly Americans stabilized. He saw how effectively they used artillery once they established proper fire direction. He saw how well they fought from prepared positions with clear fields of fire and coordinated support.

He wrote a second assessment two weeks after the battle. In it, he warned German high command not to underestimate American forces. Americans had superior equipment, superior logistics, superior numbers. What they lacked was experience. But they were gaining experience rapidly. Each battle taught them lessons. They adapted faster than British forces had.

Within a few months, RML predicted American forces would be formidable opponents. German high command ignored this assessment. Hitler and his staff believed the early Cassarene reports. Americans were weak, poorly led, would collapse under pressure. This belief shaped German strategy for the rest of the North African campaign. It also shaped German expectations for future campaigns in Sicily and Italy. The belief was wrong.

RML knew it was wrong. He had seen the evidence. The battle had taught the Americans critical lessons. First lesson, combined arms coordination. American forces learned that tanks, infantry, and artillery had to work together continuously. Splitting them into separate task forces weakened everyone. Tanks without infantry support were vulnerable to infiltration.

Infantry without tank support lacked mobile firepower. Artillery without forward observers could not respond to changing tactical situations. Everything had to work as an integrated system. Second lesson, proper positioning. Defensive positions needed mutual support. Clear fields of fire, roots of withdrawal. Isolated positions got surrounded and destroyed.

The infantry battalions on the hills at city bus had been too far apart to support each other. German armor had bypassed them, cut them off, left them irrelevant to the battle. Proper positioning meant units close enough to provide covering fire with overlapping fields of observation, able to reinforce each other quickly. Third lesson, artillery effectiveness.

American artillery properly coordinated with forward observers and pre-registered fire was devastating. It could stop German attacks cold. At Tbessa, American artillery had fired over 9,000 rounds on February 21st and 22nd. That weight of fire had destroyed German tank formations, disrupted infantry attacks, forced Raml to withdraw. The artillery had proven to be the most effective weapon system Americans possessed. But it required proper coordination.

Forward observers needed to be positioned where they could see. Fire direction centers needed accurate maps and communication with observers. Artillery batteries needed to be positioned with good fields of fire and protected from counter fire. Fourth lesson, leadership matters. The early disasters at city Bozid and Spitler happened under confused command structures.

Fred Andol had split the first armored division into multiple combat commands, given them separate missions, failed to coordinate their actions. The successful defense east of Tbessa happened under clear command with officers who understood their sectors and could coordinate their units. Robinet had unified command of combat command B. He knew every unit under his control. He knew the terrain.

He knew his mission. That clarity enabled effective action. Fifth lesson, preparation beats improvisation. The early American responses were improvised, hasty, poorly thought through. Units were committed peacemeal without reconnaissance or coordination. The later responses were deliberate, carefully planned, rehearsed. Robinet had spent two days positioning his forces at Tbessa.

He had studied the ground. He had positioned every unit deliberately. He had rehearsed fire missions with his artillery. That preparation made the difference between defeat and victory. American commanders took these lessons seriously. Major General Lloyd Fredendel, who commanded second core during Casarine, was relieved.

On March 6th, Major General George Patton replaced him. Patton immediately instituted aggressive training and rigid discipline. He required all officers to know their units, know their sectors, know their support relationships. He required units to practice combined arms coordination daily. Patton’s first action was to establish accountability.

He inspected every unit in second core personally. He asked commanders about their missions, their units, their supporting fires. If commanders could not answer immediately, Patton relieved them on the spot. Within two weeks, every battalion commander in second core knew exactly what was expected.

Clarity replaced confusion. His second action was to enforce standards. He required proper uniforms, clean weapons, military discipline. Soldiers who had grown sloppy during the retreat were brought back to standard. Patton believed discipline in garrison led to effectiveness in combat. He was correct.

Units that maintained standards in small things maintained standards in combat. His third action was to rebuild confidence. He visited forward positions daily. He talked to soldiers. He asked about their equipment, their training, their morale. He listened to their concerns. He made changes based on what he heard.

Soldiers saw that leadership cared about their welfare and their survival. Morale improved rapidly. His fourth action was to fix tactical problems. He required defensive positions to be properly cited with mutual support and clear fire plans. He required infantry and tanks to train together until they understood how to support each other.

He required artillery forward observers to work with every maneuver unit so they understood how to call for fire effectively. He required tank destroyers to practice ambush tactics from concealed positions rather than fighting tanks head-to-head. His fifth action was to prepare for offense. Casarine had been defensive, but Patton knew second core would need to attack.

He required units to practice assault tactics, movement to contact, breakthrough operations. He required logistics units to practice rapid resupply during mobile operations. He required engineers to practice clearing mines and building bridges under fire. Everything was rehearsed repeatedly until it became automatic. The results showed immediately.

American operations resumed in mid-March 1943 with a methodical advance toward the eastern dorsal on March 17th. Second core launched an offensive toward Gaffsa. Patton’s forces moved with coordinated combined arms. Infantry secured high ground while tanks provided mobile firepower. Artillery prepared each objective before troops advanced.

Engineers cleared mines and improved roads for supply vehicles. The capture of Gaffsa on March 17th was unopposed. German forces had withdrawn eastward, but Patton did not pause. He pushed second core forward immediately. On March 18th, American forces secured Elgatar, an oasis town 30 mi east of Gaffsa.

The first infantry division under Major General Terry Allen, established defensive positions in the hills surrounding the Oasis. The Germans counteratt attacked on March 23rd. The 10th Panza Division, the same unit that had smashed American forces at City Busid 5 weeks earlier, came west with 50 Panzas and mechanized infantry. They expected to drive the Americans back like they had done in February.

They were wrong. American artillery opened fire at maximum range. Forward observers positioned in the hills had clear fields of observation across the valley approaches. They called in concentrations on German assembly areas before the panzas even began their attack. Shells fell among the tanks. Some were hit, others were forced to maneuver. The attack lost cohesion before it started.

The panzas came forward anyway. They advanced across open ground toward American positions. American tank destroyers positioned hull down on reverse slopes engaged at 1500 yd. The tank destroyers were the same M3 halftracks with 75 mm guns that had failed at City Bozid.

But now they were properly positioned with clear fields of fire and infantry support on their flanks. They knocked out German tanks systematically. 28 Panzas destroyed in 4 hours of fighting. The German attack broke apart. Some tanks withdrew. Others tried to flank the American position. American artillery shifted fire to interdict the flanking movement. More German tanks were hit. The attack stalled completely.

By evening on March 23rd, the 10th Panza Division had withdrawn with heavy losses. The Americans held Elgar. This was the first time American forces had decisively defeated a German armored counterattack. The difference from City Busid was stark. Same German division, same American equipment, but completely different outcome. The change was leadership, training, and preparation.

Patton had spent four weeks rebuilding second core. The results were visible on the battlefield. The Germans attacked Elgetta again over the following week. Each attack failed. American defensive positions were too strong. American artillery was too effective.

American infantry and armor worked together too well. By early April, German forces in southern Tunisia were retreating eastward toward their final defensive lines. RML did not command at Elgar. He had been evacuated to Germany on March 9th for medical treatment. But he heard the reports. American artillery devastated German armor. American defensive positions were properly coordinated.

American forces held against everything. the Germans threw at them. This was exactly what he had predicted. The Americans in March 1943 were not the same Americans from February. They had learned, they had adapted, they had taken the lessons from Casarine and applied them systematically.

Patton had rebuilt Second Corps into an effective fighting force in 30 days. RML understood this faster than any other German commander. He understood it because he had seen the transition happen in real time during the Casarine battle. He had seen Americans break at Cid Busid, panic at Spitler, then stabilize and fight effectively east of Tbessa. The difference was not in the soldiers. It was in the leadership and the preparation.

American soldiers properly led and properly positioned fought as well as anyone. This understanding shaped RML’s later assessments of Allied capabilities. When he returned to Europe and took command of Army Group B in France in late 1943, he repeatedly warned Hitler that Allied forces, particularly American forces, should not be underestimated.

He argued that Germany’s only chance in Normandy was to defeat the invasion at the beaches before Allied forces could build up strength inland. Once established, properly supplied Allied forces with their superior equipment and artillery would be impossible to dislodge. RML’s strategic assessment was based on mathematics and logistics, not mystical beliefs about German superiority.

He calculated that Allied industrial production outweighed German production by factors of 5:1 or 10:1 depending on the weapon system. American factories were producing tanks, aircraft, and artillery at rates German factories could never match.

American logistics were bringing those weapons across the Atlantic Ocean despite German submarines. American training systems were producing competent soldiers faster than German casualties could be replaced. The combination was insurmountable. German tactical superiority could win battles. It could not win the war. The only German hope was to prevent Allied forces from establishing themselves in Europe.

Once established with their full logistical support, they would grind Germany down through sheer weight of material. RML had seen this process beginning at Casarine. American forces had poor tactics in February, but they had excellent equipment, excellent logistics, and they learned fast. By March, they had improved tactics. By May, they were winning consistently.

That trajectory would continue. Hitler ignored these warnings. Most German generals ignored these warnings. They believed the myth of German tactical superiority. They believed Allied forces, particularly American forces, were soft, inexperienced, poorly led. They pointed to Casarine as evidence. They remembered the American tanks burning at city bus.

They remembered American prisoners being marched through Tunisian villages. They remembered the chaos of the American retreat. They forgot the last two days of the battle. RML pointed to Casarine as evidence of the opposite. Americans at Casarine had their first battle, took massive losses, learned from those losses, and adapted within 72 hours.

That adaptation prevented Raml from achieving his objectives. That adaptation stopped the Africa Corps at the gates of Tbessa. That adaptation multiplied across an entire army would eventually overwhelm Germany completely. The key moment in Raml’s reassessment came on February 21st at 1400 hours when he watched the German attack stall in the Bah Fusana Valley.

He had expected to see Americans retreating in disorder like they had retreated everywhere else. Instead, he saw organized defensive fire. He saw coordinated artillery. He saw tanks fighting from prepared positions. He saw a combined arms defense that matched anything British forces had done. He immediately understood what this meant. Americans had lost battles for 9 days straight. But they had not lost their cohesion.

They had not lost their will to fight. They had fallen back, regrouped, learned, adapted. That kind of resilience was dangerous. That kind of adaptive capacity combined with American industrial strength and logistical superiority would eventually decide the war. RML expressed this view to his staff on February 23rd as they prepared to withdraw.

The Americans had taken their beating and would come back stronger. The Germans had won the battle but lost the larger opportunity. They should have destroyed second core completely in the first 3 days. They had not. Now, second core would rebuild, learn, improve. The next time they met, the Americans would be far more dangerous. His staff did not understand.

They saw the captured equipment, the prisoner counts, the territory gained. They saw victory. RML saw missed opportunity and future threat. The historical record proves RML right. American forces in North Africa improved dramatically after Casarine. By April, they were holding their own against German attacks. By May, they were leading offensives.

By May 13th, when Axis forces in Tunisia surrendered, American forces had evolved into competent, effective combat units. The same pattern repeated in Sicily in July 1943. Initial American difficulties, rapid adaptation, eventual success again in Italy in September 1943. initial setbacks, quick learning, steady advance.

By June 1944, when Allied forces landed in Normandy, American units were among the most effective forces in the European theater. RML never fought Americans again after Casarine. He left North Africa in March, spent time in Italy, then moved to France to prepare defenses against the expected invasion. But his experience at Casarine informed his strategic thinking for the rest of the war.

He knew what Allied forces, properly equipped and properly led, could accomplish. He knew Germany’s only chance was to prevent them from establishing a foothold. Once established, they would be unstoppable. On June 6th, 1944, Allied forces landed at Normandy. Raml was not at his headquarters. He was in Germany celebrating his wife’s birthday.

By the time he returned on June 7th, Allied forces had established their beach head. By June 10th, they had landed over 300,000 troops and were pushing inland. Raml immediately recognized the situation. The Allies were established. They would build up strength. Germany could not stop them. The war was lost.

He was injured on July 17th when Allied aircraft strafed his staff car. He was recovering when he was implicated in the July 20th plot to assassinate Hitler. Given the choice between a trial and suicide, he chose suicide on October 14th, 1944. He was 52 years old. His assessment of American forces, written after Casarine and refined over the following year, remained in German military archives. Historians found it decades later.

It stands as one of the most accurate early evaluations of American military potential in World War II. Paul Robinet survived the war. His defensive stand east of Tbessa on February 21st was officially credited with stopping the German advance and saving Tbessa.

He was wounded on May 5th, 1943 when German artillery hit his jeep. His left leg was severely damaged. He was evacuated to the United States and retired from combat operations. He later commanded the armored school at Fort Knox until the end of the war. Robinet never received widespread recognition for his role at Casarine. The battle was remembered as an American defeat.

The early disasters at City Build and Spitler dominated the historical narrative. The successful defensive stand that stopped RML was overshadowed by the earlier losses. But Robinet knew what he had accomplished. his careful preparation, his coordination of combined arms, his deliberate defensive positioning, these had stopped the desert fox at the moment when German victory seemed inevitable.

He had shown that Americans, properly led and properly prepared, could defeat German forces on equal terms. George Patton knew it, too. When he took command of second corps in March, he met with Robinet and asked for detailed debriefs on the defensive actions east of Tbessa.

Patton used those lessons to rebuild second core. Everything Robinet had done, the combined arms coordination, the artillery preparation, the defensive positioning, pattern made standard practice across the entire core. By May 1943, second core was a different force. They advanced across Tunisia, fought through German defensive lines, captured thousands of prisoners.

On May 7th, they entered Berser. On May 13th, all Axis forces in North Africa surrendered. Total prisoners captured, 275,000 German and Italian soldiers, more than were captured at Stalingrad. The transformation took 12 weeks from the disaster at Casarine in midFebruary to total victory in mid-May. 12 weeks of learning, adapting, training, fighting.

12 weeks that proved RML’s assessment correct. American forces were not inferior to German forces. They were inexperienced. Experience could be gained. Lessons could be learned. Mistakes could be corrected. The speed of that learning process determined outcomes. At Casarene, Americans learned in 72 hours. At city Bozid and Spitler, they fought poorly.

East of Tbessa, they fought well. That transition compressed into three days of combat showed what American forces were capable of when properly led. RML saw this. Most German commanders did not. That difference in perception shaped how different commanders approached the war. RML advocated for realistic assessments and defensive strategies based on Germany’s deteriorating strategic position.

Other commanders advocated for offensive operations based on assumed German superiority. The offensive approach failed repeatedly in Tunisia, in Sicily, in Italy, in France. German forces attacking well-prepared Allied positions suffered heavy casualties and gained little. The defensive approach worked better, but could not change the strategic situation.

Germany lacked the resources to defeat the combined Allied forces regardless of tactics. By early 1944, RML had concluded the war was unwinable. His experience at Casarine had taught him that Allied forces once established and properly supplied could not be defeated by tactical superiority alone. Germany needed a political settlement. Germany would not get a political settlement.

Therefore, Germany would lose. He was correct. But his correctness changed nothing. Germany fought on until May 1945. Millions more died. Cities were destroyed. Europe was devastated. All of it might have been prevented with realistic assessments. In 1943, Kasarine Pass was one of those moments where reality became visible. The early battles showed American weaknesses.

The later battles showed American strengths. Raml saw both. He understood what the combination meant. He tried to warn his superiors. They did not listen. That is how military failure happens. Not through lack of courage or skill, but through false assessment and wishful thinking.

German commanders in 1943 wanted to believe Allied forces were weak. Some evidence supported that belief. The disaster at city Buzz, the chaos at Spitler, the early breakthrough at Casarine Pass. But other evidence contradicted it. The defensive stand east of Tbessa, the artillery fire that stopped German attacks, the rapid American adaptation. RML weighed all the evidence.

He concluded the contradictory evidence was more important than the supporting evidence. Americans could learn. Americans could adapt. Therefore, Americans would eventually win. That conclusion was unpopular. It was also accurate. The Battle of Casarine Pass ended 79 years ago. Historians still debate its significance.

Some emphasize the American defeat, the casualties, the captured equipment. Others emphasize the lessons learned, the rapid adaptation, the successful defensive actions that stopped Raml short of his objectives. Both perspectives are partially correct. Casarine was a defeat. Americans lost more men, more equipment, more ground than the Germans. But Casarine was also a learning experience.

Americans figured out combined arms coordination under fire. They figured out artillery effectiveness. They figured out defensive positioning. They applied those lessons immediately. RML understood that paradox. You can lose a battle and learn enough to win the war. You can win a battle and miss strategic realities that guarantee eventual defeat.

Kasarine was both simultaneously an American tactical defeat that became a strategic lesson. A German tactical victory that revealed American potential. The field where Paul Robinet positioned his defense on February 21st is empty farmland now. No markers, no monuments. The wadis where he hid his tanks are still there. The ridgeel lines where his artillery observers called in fire are still there.

The valley floor where German panzas were destroyed is still there, but nothing marks what happened. Most people driving through do not know a battle was fought there. RML’s headquarters at Casarine is gone. The pass itself is now a modern highway. Tourists drive through without knowing its history.

The hills where American and German soldiers fought are quiet, but the lessons remain. Proper preparation matters. Combined arms coordination matters. Leadership matters. Realistic assessment matters. These lessons learned at great cost in February 1943 shaped how American forces fought for the rest of the war. RML learned those lessons, too.