At 6:58 a.m. on October 25th, 1944, the sky off Samar looked like it couldn’t decide what it wanted to be. The rain came in curtains—thin in one direction, thick in another—dragged sideways by wind that whipped the sea into short, angry chop. Visibility flickered with every squall: one moment you could see the horizon, the next it was erased as if someone had wiped the world clean.

Commander Ernest E. Evans stood on the bridge of USS Johnston and watched the horizon reappear in pieces.

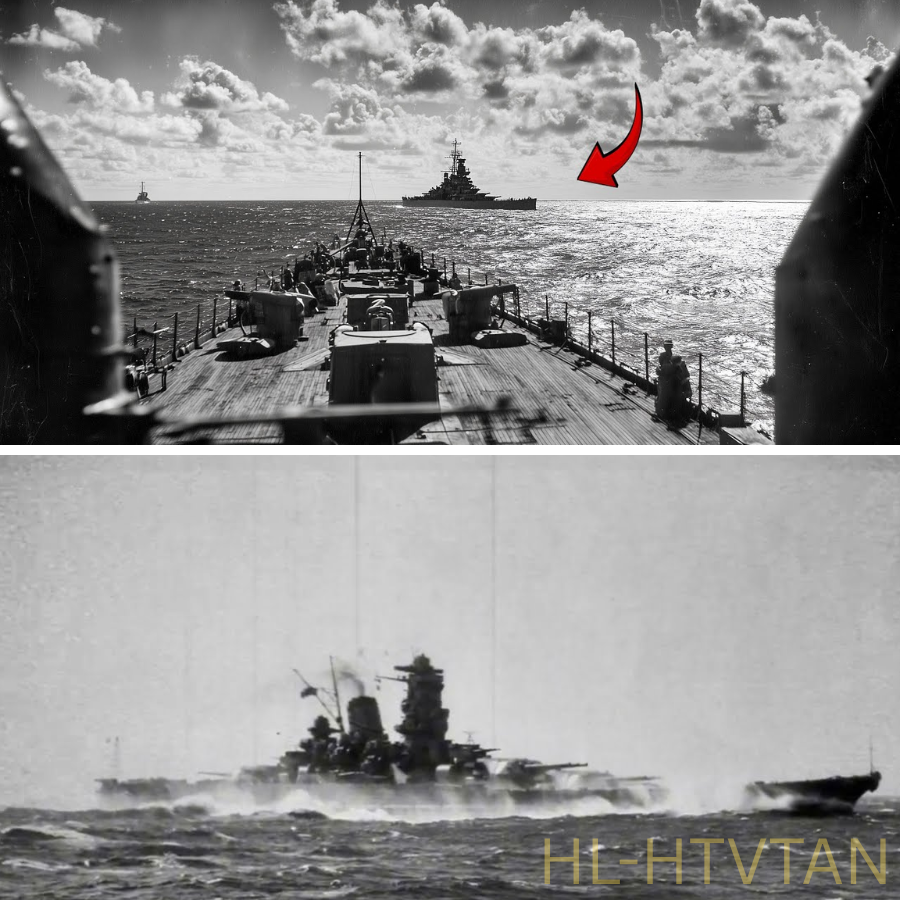

First the sea line. Then the vague dark silhouettes. Then—like monsters stepping out of fog—the pagoda masts and tall superstructures of warships that did not belong in this part of the ocean.

Four battleships.

Six heavy cruisers.

Light cruisers. Destroyers.

And leading them—vast beyond reason—was Yamato, the biggest battleship ever built, a floating fortress that had been designed to kill other fortresses.

In a different kind of war, men might have stared in awe.

Evans stared with calculation.

He was thirty-six years old, with Cherokee and Creek ancestry and a childhood that had taught him something useful long before the Naval Academy did: if you were going to be judged, you might as well be judged for doing something bold. He had grown up in Oklahoma. He had graduated from Annapolis in 1931. He had spent thirteen years rising rank by rank in a Navy that was now fighting at full speed in two oceans at once.

When Johnston was commissioned a year earlier, Evans had stood in front of his crew and told them plainly what kind of ship they were going to be.

A fighting ship.

A ship that would go into harm’s way.

A ship whose captain would not hesitate.

If anyone didn’t want to go along, he’d said, get off now.

No one got off.

Now, in the rain off Samar, those words stopped being a speech and became a sentence.

The mathematics were insulting.

Yamato displaced about 72,000 tons. Johnston displaced about 2,700. Yamato’s main guns fired shells that weighed roughly as much as a pickup truck—over 3,000 pounds—projectiles that could cross miles of sea and hit with such force that they didn’t merely punch holes; they erased steel. Johnston’s main battery fired 5-inch shells—fifty-five pounds each—good weapons against destroyers and aircraft, capable of tearing open a cruiser’s superstructure if you got close enough, but not weapons designed to duel battleships in daylight.

Behind Johnston and the other escorts, the ships they protected weren’t even “real” carriers in the way people imagined carriers. Taffy 3—Task Unit 77.4.3—was a group of six escort carriers: Fanshaw Bay, St. Lo, White Plains, Kalinin Bay, Kitkun Bay, and Gambier Bay. They were converted merchant hulls with flight decks welded on, built to provide anti-submarine patrol and close air support for troops. Their aircraft—FM-2 Wildcats and TBM Avengers—were tough and useful, but they weren’t meant to stop a line of battleships. They were meant to hunt submarines and bomb beach targets.

And now those slow little carriers were about to be hunted.

Three destroyers screened them: Johnston, Hoel, and Heermann. Four destroyer escorts—smaller ships, less armored, less armed—rounded out the protection: Samuel B. Roberts, Dennis, John C. Butler, and Raymond.

That was it.

Seven warships guarding six escort carriers and the broader invasion support shipping behind them.

Against the last powerful surface action group the Imperial Japanese Navy could still assemble.

The enemy force wasn’t supposed to be here.

American intelligence had said the Japanese battleships were hundreds of miles north, tangled up with Admiral Halsey’s fast carriers. That assumption had been comfortable. It had been wrong.

Halsey had chased a decoy. The Japanese had executed a three-pronged plan. The northern force—the decoy—had done its job perfectly, pulling American carriers away. The central force had slipped through San Bernardino Strait in the night, unseen and unopposed, and now it had the invasion beaches in front of it.

It wasn’t just a surprise.

It was a knife sliding in behind the ribs.

At 6:47 a.m., lookouts on the escort carriers had first spotted the pagoda masts. At 6:58, Yamato opened fire from about seventeen miles away. The first salvo fell short of White Plains—but the shell splashes weren’t like normal splashes. Each impact threw up a column of water as tall as a building, geysers that made the sea look like it was erupting.

And the splashes were colored.

Japanese gunnery crews dyed shells—red for one ship, blue for another, green for another—so spotters could identify whose rounds were landing where. To an American sailor watching, it looked surreal: colored plumes blooming in gray water, as if the ocean itself was bleeding ink.

Admiral Clifton Sprague, commanding Taffy 3 from Fanshaw Bay, ordered the carriers to make smoke and launch every aircraft. He ordered the escorts to lay smoke and prepare torpedo attacks. He ordered the carriers southeast, toward a rain squall eight miles away—a natural curtain they could hide behind for precious minutes.

But the carriers could make seventeen knots at best.

The Japanese battleships could make twenty-five.

At that closing speed, the enemy would overtake them quickly.

Evans didn’t wait for a formal command to attack.

At 7:00 a.m., he ordered flank speed and turned Johnston directly toward the Japanese fleet.

It was not a romantic choice.

It was a tactical one.

If the battleships and cruisers kept their guns focused on the carriers, the carriers would be slaughtered and air support for the Leyte landings would be wiped out. The invasion—MacArthur’s return—would collapse under the weight of Japanese naval gunfire and air attack.

The carriers needed time.

Time to run.

Time to hide.

Time to launch aircraft that could at least harass the attackers, force maneuvers, break fire-control solutions, create confusion.

Time, in war, is bought with blood.

Evans was about to spend his ship like currency.

In the engine room, Lieutenant Joseph Worthington pushed the machinery hard. Johnston surged to about thirty-three knots, throwing spray and cutting through chop with the aggressive forward lean of a destroyer at full throttle. Smoke poured from funnels as the ship laid its own artificial fog, joining the smoke from other escorts until the sea behind Taffy 3 began to vanish in a white-gray wall.

Evans ordered all weapons manned.

Ten 5-inch guns in five twin mounts. Ten torpedo tubes in two quintuple mounts. 40mm and 20mm anti-aircraft batteries. A destroyer’s arsenal—fast-firing, sharp, dangerous—built for screens and attacks, not for trading punches with battleships.

But Evans wasn’t planning to trade punches.

He was planning to stab.

Lieutenant Robert Hagen, the gunnery officer, stood in the main battery director above the bridge. The director was an armored box with optics and mechanical computers, a brain that translated range and bearing into firing solutions. Hagen watched the Japanese ships grow larger through the optics while calling out ranges.

Thirty-five thousand yards.

Thirty thousand.

The carriers were already taking fire. Huge splashes bracketed Fanshaw Bay. Salvos landed on both sides of White Plains almost simultaneously, like the sea snapping shut.

Johnston ran through her own smoke, then curved to the northwest—evading, closing, using the smoke as a moving shield. It was a classic torpedo attack approach: hide the approach, close to effective range, launch, then disappear again before the enemy can concentrate fire.

The textbook version of that tactic assumed you had other heavy ships supporting you.

Evans had no heavy ships.

He had only intention.

At 7:10, Johnston punched out of the smoke about 18,000 yards from the Japanese line. The first clearly visible target was a heavy cruiser—Kumano—with Yamato looming behind like a dark cliff. Hagen’s rangefinder locked on.

18,000 yards.

Still too far for torpedoes. The Mark 15 torpedoes had their own mathematics: at high-speed settings, their effective range was around 10,000 yards. Evans needed to close another 8,000 yards under the gaze of battleships and cruisers that could erase his ship with a handful of hits.

At 7:13, Japanese shells began to fall around Johnston.

The first salvos were short. They were calibrating.

The next straddled. Water columns rose on both sides, so close the spray slapped the destroyer’s decks and rattled fittings.

Then came hits.

Three 14-inch shells—likely from a battleship—hammered Johnston’s stern. The shock was physical, as if the ship had been punched by a giant. Explosions tore through compartments. Men in the aft engine room died instantly. Machinery screamed and went silent. One of Johnston’s two engines was knocked out.

Speed fell.

Thirty-three knots to seventeen.

Steering from the bridge went dead.

Evans didn’t retreat.

He ordered steering shifted to aft control. He ordered Worthington to keep the remaining engine running.

And he kept closing.

Fifteen thousand yards.

Thirteen.

Shells landed continuously now, many missing, some hitting. Johnston’s armor—thin by design—was meant to stop fragments, not full-caliber shells. When big rounds hit, they punched through hull plates like a fist through cardboard, detonating inside the ship, turning corridors into storms of metal and fire.

But a destroyer’s advantage was that it could move unpredictably. Evans maneuvered hard, zigzagging, changing speed when he could, using smoke and squalls like chess pieces.

At 7:16, Johnston reached torpedo range—about 10,000 yards.

Evans ordered all torpedoes fired.

Ten Mark 15s splashed into the sea and ran straight at forty-five knots, invisible killers racing beneath waves toward steel giants.

Immediately, Evans swung the ship hard to starboard, reversing course back toward the carriers and smoke.

That turn exposed Johnston’s side to the Japanese line—and the punishment intensified.

A shell slammed into the bridge area. Glass and metal erupted. Three officers died in that instant. Shrapnel tore into Evans, ripping his shirt and taking two fingers from his left hand.

He wrapped a handkerchief around the wound and kept giving orders from the bridge wing like pain was a minor inconvenience.

Hagen, knocked backward by the blast, staggered back to his station and resumed calling ranges. The director was damaged. The fire-control radar was gone. But the optics still worked. If you could see a target, you could still shoot.

At 7:18, one of Johnston’s torpedoes struck Kumano.

The explosion blew off a chunk of the cruiser’s bow—forty feet of forward hull gone in an instant. The heavy cruiser turned away, flooding forward, speed collapsing. Out of the fight.

A destroyer had just crippled a heavy cruiser at the heart of a battleship formation.

Evans pushed Johnston back into smoke.

The first attack run had lasted minutes, but in those minutes Johnston had done what larger ships were supposed to do: force the enemy to maneuver, disrupt formation, and make the attacker pay attention to the screen instead of the carriers.

Inside the smoke, damage control teams fought flooding. Men carried hoses. Men passed stretchers through narrow corridors. The after engine room was flooded. One fire room was out. The ship was down by the stern, listing. One 5-inch mount was destroyed. A 40mm mount was wrecked.

Twenty dead. Fifteen wounded.

And yet the ship still moved.

Seventeen knots wasn’t enough to outrun battleships.

But it was enough to keep fighting.

At 7:20, Sprague finally ordered the destroyers to make torpedo attacks. Hoel and Heermann moved out to do what Johnston had already done.

Evans brought Johnston out of smoke to support them with gunfire.

He watched Hoel make a direct run at the battleships like a man charging a firing line. Commander Leon Kintberger fired torpedoes around 7:27 at roughly 9,000 yards. The Japanese battleships turned away to evade—whether the torpedoes hit or missed mattered less in that moment than the fact that they forced the big ships to maneuver.

Maneuvering broke the gunnery solutions. Maneuvering burned time.

But the price was terrible.

Japanese shells found Hoel. Hits piled up. Flooding spread. Speed dropped. The destroyer was reduced to a wounded animal, surrounded by cruisers that closed in for the kill. Eventually, Kintberger ordered abandon ship. Hoel capsized and sank.

Meanwhile Heermann completed her torpedo run, launching at closer range, then slipping away under smoke with luck and skill. She survived.

And Johnston, now without torpedoes, returned to the role of bodyguard—placing itself between Japanese cruisers trying to flank and the vulnerable carriers fleeing southeast.

This was the heart of the Battle off Samar: chaos threaded through smoke and rain, with tiny American ships turning themselves into moving walls.

The carriers had reached a rain squall, disappearing briefly. But by around 7:30 they emerged again, exposed. Japanese cruisers—fast, heavy-gunned—began moving to intercept from the east. If they succeeded, the escort carriers would be trapped between battleships and cruisers.

Evans saw the shape of the trap.

He turned Johnston toward the cruisers and opened fire at 7:38.

At fourteen thousand yards, 5-inch shells couldn’t punch through cruiser armor belts. But they could do something else: they could wreck the exposed parts that made cruisers lethal—fire-control stations, rangefinders, communications gear, gun crews.

The shells splashed around Tone and forced the cruiser’s gunners to adjust. More importantly, they forced Tone to pay attention.

Tone and Chikuma returned fire. Great fountains rose around Johnston as 8-inch shells landed close. Evans maneuvered continuously—zigzagging, slipping into smoke, darting out to fire, then vanishing again.

The destroyer wasn’t trying to win by damage.

It was trying to win by disruption.

At 7:50, another American ship joined the fight in a way that still seems almost impossible to imagine.

USS Samuel B. Roberts, a destroyer escort—smaller than a destroyer, less armed, less armored—charged into the cruiser fight like it was a battleship.

Lieutenant Commander Robert Copeland closed to around 5,000 yards from Chikuma and launched torpedoes. One struck, jamming the cruiser’s rudder. Chikuma began to circle, crippled by a ship it should have ignored.

Samuel B. Roberts hammered the cruiser with 5-inch fire at near point-blank range, starting fires, killing crew, smashing equipment.

Japanese return fire was merciless. The little escort was torn apart. Flooding took engines. Guns were knocked out. Copeland eventually ordered abandon ship. Samuel B. Roberts sank.

The escort carriers were still running.

The destroyers and destroyer escorts were dying.

And the Japanese force—so much larger, so much stronger—began to lose cohesion.

That was the strange, fragile truth of Samar: Kurita’s battleships and cruisers were powerful, but power depends on clarity. Smoke screens and relentless torpedo threats denied clarity. Aircraft—Avengers and Wildcats—kept swooping in, dropping whatever they had, even depth charges when bombs weren’t available, forcing the Japanese to maneuver and break formation.

American pilots attacked knowing their weapons weren’t ideal. They attacked anyway, because any disruption mattered.

By around 8:10, Japanese cruiser Chokai closed and landed heavy hits on Johnston, wrecking aft structures and disabling steering again. Evans shifted to manual rudder control below decks. Sailors turned a massive wheel by hand, responding to shouted orders relayed through voice tubes and runners.

It was slow. It was crude.

It worked.

At 8:20, the escort carriers launched another wave. The sky above Samar filled with desperate American aircraft—Avengers carrying torpedoes and bombs, Wildcats dropping 500-pounders. Some torpedoes hit or forced evasions. Yamato herself reportedly turned away temporarily under torpedo threat, a huge battleship forced to maneuver by aircraft that were never meant to duel it.

The Japanese gunnery problem worsened. Battleship guns are lethal when they can compute a solution and hold it. If targets vanish in smoke and rain, if you keep turning to dodge torpedoes, if aircraft keep forcing you to break formation, even the largest guns become frustrated giants.

But frustration doesn’t save ships forever.

By 8:30, the escort carriers were battered. Gambier Bay slowed. Fires burned. Hits accumulated. The Japanese were still closing.

And Johnston kept fighting, placing her battered hull between the cruisers and the carriers like a man throwing his own body into a doorway to hold it shut.

Her 5-inch guns fired and fired. Ammunition crews fed shells. Hagen kept directing with optics in a director that had been blown open, standing amid ruin and still doing his job.

At 8:40, the fight caught up to Johnston.

Japanese heavy cruiser fire—8-inch shells—slammed into the destroyer. Three hit nearly together. One destroyed the forward engine room. The last functioning engine died. Power vanished. Another shell destroyed a forward gun mount, killing its crew. Fires spread through wrecked compartments.

Johnston went dead in the water.

A destroyer is a predator because it moves. Without movement, it becomes prey.

Evans assessed the ship quickly, as if reading a casualty list in his own hands. Both engines destroyed. Fire rooms flooded or out. Emergency batteries only. Three of five main gun mounts out. The remaining guns still firing on local control, crews doing their jobs without central direction.

But the ammunition hoists were dead. Shells had to be passed by hand.

When a ship loses power, it begins to die in slow motion.

Evans ordered the remaining guns to keep firing until they could not.

Japanese destroyers began to close in, sensing blood.

At 9:00, three Japanese destroyers approached within a few thousand yards and opened fire. Torpedoes splashed into the sea. Shells tore into Johnston at point-blank range. The destroyer—already battered, listing, burning—was being executed.

Evans ordered abandon ship at 9:20.

Men went over the side. Some were wounded. Some couldn’t swim. Sailors helped each other, pushed rafts into water, pulled friends along. The sea that had been background a few hours earlier now became the last battlefield—a cold, rolling place where survival depended on strength, luck, and whether rescue arrived in time.

Japanese destroyers ceased fire and moved away. One Japanese captain reportedly saluted as Johnston sank—an acknowledgement that what they had witnessed was not merely resistance, but defiance.

At 9:45, Johnston rolled and went down stern-first. The bow rose, held for a moment like a monument, then slipped beneath the sea.

Commander Ernest E. Evans did not leave his ship.

He was last seen on the bridge. His body was never recovered.

Of Johnston’s crew of 327, 186 died.

Some died in action. Others died in the water—wounds, exhaustion, exposure. Rescue ships didn’t arrive until two days later. Men who had survived the battle itself drifted and waited and died under sun and shark and salt.

And yet even with those losses—Gambier Bay sunk, Hoel sunk, Johnston sunk, Samuel B. Roberts sunk—Taffy 3’s sacrifice did something that still feels almost impossible when you look at the numbers:

It stopped Kurita.

Admiral Takeo Kurita had expected to fight American fleet carriers protected by battleships and heavy cruisers. He believed he had stumbled into the edge of a much larger American force. Smoke screens prevented accurate identification. Torpedo attacks came with such aggressiveness that Japanese officers assumed larger ships must be present. The destroyers fought with the ferocity of capital ships, and the constant air attacks—however imperfect—added to the sense that Kurita was facing more than he actually was.

The Japanese formation scattered. Cruisers took damage. Destroyers were pulled into evasive maneuvers. Yamato turned away at least once, temporarily abandoning a direct pursuit.

At 9:25, Kurita ordered his ships to regroup. They turned north, away from the carriers. Reports reached him—false reports—that American fleet carriers were approaching from the east. Kurita believed he might be trapped between two American forces.

At 12:36, he ordered withdrawal.

The Japanese force turned back through San Bernardino Strait and abandoned the attack.

The invasion shipping survived. The carriers—what remained of them—survived. MacArthur’s Leyte operation continued.

The Japanese Navy never again seriously threatened American amphibious operations in the Philippines.

The cold arithmetic of the battle is grim. Taffy 3 lost ships and men. The Japanese lost heavy cruisers and thousands of sailors. But the key outcome wasn’t a neat exchange ratio.

It was time.

Taffy 3 bought time.

Three hours of time that protected an invasion.

Three hours that kept air support alive.

Three hours that changed a campaign.

That was the strange, brutal power of sacrifice at sea: a small ship could be destroyed, but in the act of being destroyed it could alter the decisions of giants.

After the war, Evans received the Medal of Honor posthumously. His crew received decorations in numbers that still stand out: Navy Crosses, Silver Stars, Bronze Stars—testimony that what happened off Samar was not a routine fight, but something closer to legend made real.

Japanese officers later admitted, in postwar interviews, that the American destroyers fought with a ferocity they had rarely seen. One specifically mentioned a destroyer that kept firing even after losing power and being surrounded.

That destroyer was Johnston.

Decades later, in 2019, the wreck of Johnston was located deep in the Philippine Sea—more than 21,000 feet down, in darkness so complete it feels like another planet. Remote vehicles photographed the hull. Damage matched battle reports: the number still visible, the forward mount destroyed, the stern shattered.

The wreck was declared a protected war grave.

No artifacts were recovered.

Because some places are not museums.

They are tombs.

The last survivors of Johnston held reunions for years, gathering as old men to remember what they had been as young men. In interviews before the last of them died, they were asked why Evans charged the fleet alone.

They said Evans never explained.

He simply gave the order—flank speed, turn toward the enemy—and the crew trusted him completely.

They were asked if they were afraid.

They said yes.

Everyone was afraid.

But fear didn’t matter.

The job was to protect the carriers.

So they did the job.

That is the uncomfortable, unromantic truth beneath the romance of heroism: courage is often just the willingness to do what must be done while fully aware of the odds.

Evans knew Johnston would probably sink.

Most of the crew knew it too.

But the carriers had to be protected.

Someone had to buy time.

Johnston bought it.

And in the rain squalls off Samar, where battleships fired shells heavier than trucks and a destroyer answered with fifty-five-pound rounds and torpedoes, the victory did not belong to the side with the larger guns.

It belonged to the side that refused to accept the logic of retreat.

The mathematics favored Japan.

The courage favored Johnston.

And that morning, courage bent mathematics just long enough for history to change course.