At 2:47 in the afternoon on March 24th, 1942, the Supermarine Spitfire stopped being an airplane and became a falling argument with gravity.

Flight Lieutenant Bill Ash felt it before he saw it—the shudder through the airframe, the sudden slackness in the controls, the way the engine’s note changed from a steady growl into something sick and uneven. Smoke spilled past the canopy like a dark ribbon. His right hand tightened on the stick. His left hovered, useless, over switches that suddenly seemed like wishful thinking.

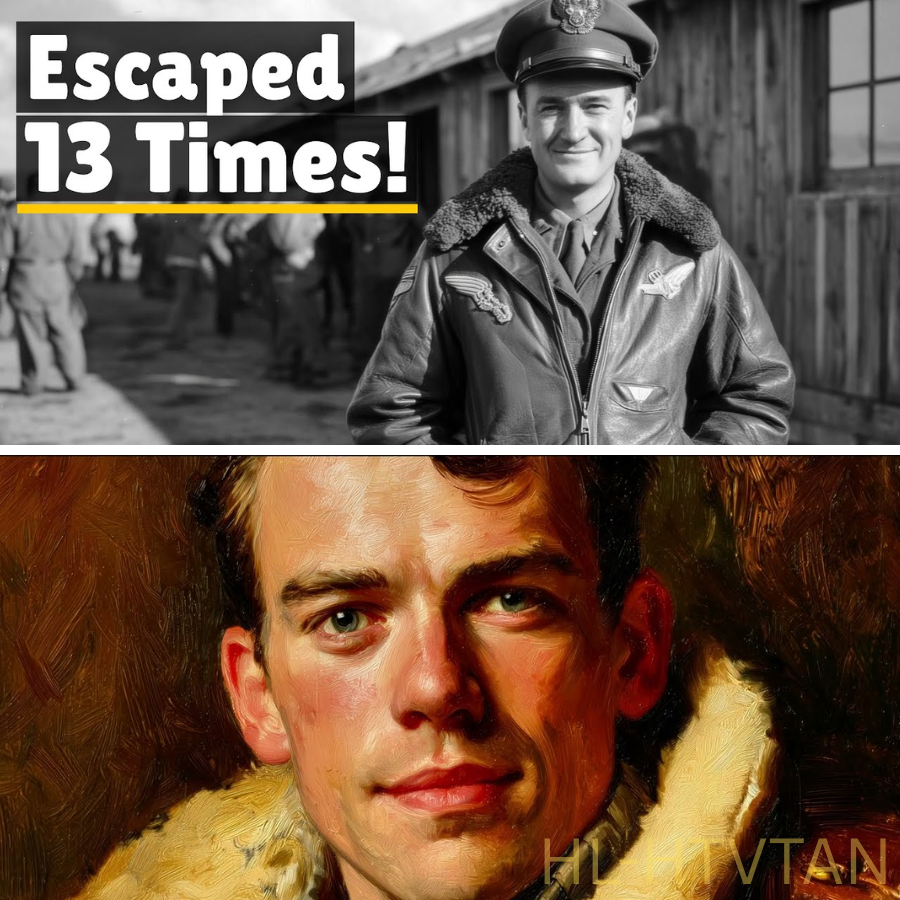

He was twenty-four years old. He spoke with a Texas drawl that never quite left him no matter how many months he spent in English mess halls. He had exactly one confirmed kill in his entire combat career, which made him, by the standards of men who counted victory in tallies, a footnote. But there was a difference between being mediocre in the air and being soft on the ground. The sky could judge you harshly. The ground, Bill Ash had learned, rewarded a different kind of skill.

German fighters had jumped his formation over a power station in occupied France. He’d done what he was supposed to do—keep the target in sight, keep the flight together, keep moving—until the Spitfire took hits and the engine began to die. He tried to limp back toward the Channel. He got as far as eight thousand feet.

Then the engine quit.

Silence hit like a punch. Not total silence—there was wind, there was vibration, there was the whistle of air tearing around wings—but the comforting mechanical heartbeat was gone. A pilot in that moment didn’t think about philosophy or patriotism. He thought about angles, distance, fields, fences, and whether the machine would give him one last chance.

Ash glided the crippled Spitfire down toward a patchwork of fields. He picked one that looked flat enough and empty enough. He came in hard. The landing gear collapsed. The aircraft skidded through wet ground, plowing mud like a reluctant plow horse, and finally stopped against a fence with a violent jolt that snapped his head forward. His ears rang. Blood warmed his upper lip.

For ten seconds he sat in the cockpit breathing hard, hands still on the controls like he could will the plane back into the air.

Then he looked up.

German soldiers were running across the field toward him.

Bill Ash unbuckled his harness and climbed out into cold air that smelled of damp soil and burning oil. His legs shook, not from fear exactly—fear had a cleaner taste in the air—but from adrenaline and impact and the sudden understanding that this wasn’t a bad landing. This was captivity.

He stood beside the wreckage, raised his hands, and waited.

The first German to reach him was barely more than a boy, cheeks round, eyes bright. He wore a grin like capturing an enemy pilot was a prize. Other soldiers gathered, rifles pointed. Someone shouted a command.

Ash stared at the young private and, in that slow Texas accent that sounded almost friendly even when it wasn’t, said, “You boys are gonna be real disappointed. I’ll be out of here before the month’s over.”

The private laughed. The others laughed too. It was a good joke, a cocky joke, the kind of thing that made a captured pilot sound like he was trying to hold onto bravado because he had nothing else.

They didn’t know it wasn’t bravado.

It was a promise.

Bill Ash had been born into the kind of poverty that didn’t have romance in it.

Depression-era Dallas didn’t care about dreams. It cared about rent, about food, about whether the lights stayed on. His father was what Bill later called a “failed salesman,” which sounded gentler than the reality. The family lived, as Bill put it, not in white-collar circumstances but in frayed-collar ones—clothes worn thin, shoes patched, pride held together with stubbornness.

When the stock market crashed, it wasn’t abstract to Bill. It ate his future in dollars and cents. He’d scraped together two hundred dollars—every penny earned stacking shelves, taking small jobs, writing essays for rich kids who didn’t bother doing their own homework—and watched it vanish like smoke.

He worked his way through the University of Texas anyway. He rode freight trains as a hobo during the worst years, sleeping where he could, learning the hard math of hunger. He boxed in amateur matches for extra money, because violence was one of the few markets that always had demand. He took punches and learned which ones were survivable. That lesson would matter later, in ways he couldn’t have predicted.

He hated fascism with a kind of personal intensity, not because he’d read the right books—though he read plenty—but because he hated bullies. The world, in his experience, was full of men who wanted to dominate others and call it order. Fascism was that impulse given uniforms and flags.

He nearly went to Spain to fight with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade before the war there ended. It felt like missing a train you’d been ready to jump onto. So when Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany in 1940, Bill didn’t wait for America to get involved. He didn’t wait for permission.

He crossed from Detroit to Windsor and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

It cost him his American citizenship. Joining a foreign military meant forfeiting it automatically. The paperwork said he wasn’t American anymore.

Bill didn’t care. He wanted to fight fascists more than he wanted a passport.

The RCAF sent him to Britain. He trained on Spitfires. He flew with squadrons over the Channel, escorting bombers, attacking ships, defending convoys. He watched the sky fill with contrails and death. He learned quickly that courage didn’t make you good at aerial combat. Skill did. Instinct did. Luck did.

In two years of fighting, he shot down one German aircraft.

One.

His fellow pilots had five, ten, fifteen. They were aces. They were legends. Bill was… serviceable. Competent. Brave. Not great. He knew it, and he carried it like a private irritation. He wanted more. He wanted to be the kind of pilot who made a difference in the air.

Instead, his real legend would be built in places where there was no sky at all.

After the crash, the Germans did what Germans did with captured officers: they processed him.

At a local command post they asked the usual questions—name, rank, serial number. Bill gave them exactly that and nothing more. When they asked about his squadron, his base, aircraft performance, he stared at the wall as if the wallpaper fascinated him.

Two hours later, they sent him to a transit camp.

Within a week, the French Resistance made contact.

They were good at their work—quiet networks of courage that moved men like pieces across a board. Downed pilots were smuggled through safe houses, hidden in barns, guided to routes leading south toward Spain. The Resistance told Bill to stay hidden, keep his head down, wait. They spoke to him like a man who needed to be protected from his own impatience.

Bill listened politely.

Then he did the opposite.

Paris, to him, was an irresistible temptation. Not because he wanted romance or adventure. Because he refused to behave like a hunted animal. He walked the streets like a tourist. He went to museums. He wandered art galleries. He sat in cafés and drank bitter substitute coffee that tasted like regret. He swam in public pools. He looked at the city as if it belonged to everyone, as if German occupation was temporary—because in his mind, it was.

The Resistance handlers were horrified.

“Paris is crawling with informers,” they warned. “The Gestapo is everywhere. You will get caught.”

Bill shrugged with that Texas stubbornness. He said he’d been in prison camps before—he hadn’t, but he’d been hungry and poor and he’d learned you could survive a lot if you refused to bow your head.

In late May 1942, the Gestapo arrested him in a café on the Left Bank.

They didn’t treat him like an ordinary POW. He was in civilian clothes. Under German law, that made him a spy. Spies were not protected the way captured officers were. Spies could be executed without trial, without negotiation.

They took him to Fresnes.

Fresnes wasn’t a normal prison. It was where the Gestapo sent people they planned to kill.

Bill spent three weeks expecting a walk down a corridor that ended in a wall. He spent those weeks refusing to give the Gestapo what they wanted. They beat him. They kept him in darkness. They demanded names of Resistance contacts. Bill gave them nothing.

Fear was real in Fresnes, but it didn’t control him. He had always been poor. He had always been stubborn. The Gestapo could hurt him, but they couldn’t bargain with him.

A Luftwaffe officer eventually intervened. Someone, somewhere, understood that executing an Allied pilot would invite reprisals against German airmen held by Britain. Bill was transferred back into Luftwaffe custody.

That transfer probably saved his life.

It also ensured he would spend years making German camp commanders regret it.

Oflag 21B in occupied Poland was where the Germans sent captured Commonwealth officers. It was surrounded by tall wire fences, guard towers, searchlights, dogs. The commandant gave new arrivals a speech about futility. Escape was impossible. Attempting it would earn punishment. Repeat attempts would lead to worse.

He looked directly at Bill when he said it.

Bill smiled right back.

The first time Bill walked out of the camp, it wasn’t through a tunnel or a brilliant trick. It was through a simple identity swap.

A work detail was leaving the camp—men marched out under guard to dig ditches and do labor outside the perimeter. Bill traded identity with someone assigned to the detail. The guards checked numbers, not faces. Bill marched out through the front gate like he belonged there.

For a couple hours he worked with a shovel, head down, body moving like any other prisoner. Then, when the guards’ attention drifted, he simply… walked away.

He made it less than a kilometer before a guard on horseback ran him down.

Back in camp, the commandant sent him to “the cooler”—solitary confinement. A small cell. Cold. Minimal food. Nothing to do but sit with your own thoughts.

The Germans believed solitary confinement broke men. Sometimes it did.

With Bill, it sharpened him.

He used the cold days in the cooler the way he used time on the ground before flights: he rehearsed, reviewed, and adjusted. What had he done wrong? Where had he been seen? How could he do it better?

The second major attempt involved a bigger effort—dozens of men, a long tunnel, hope stretched into the dark. Bill crawled out beyond the wire and felt the night air hit him like freedom. He walked for days, hiding, scavenging, trying to reach a city where underground contacts might exist.

They were caught at a station when a local policeman looked at their forged papers and knew—immediately—that something was wrong.

Bill returned to the camp with thirty days of solitary confinement waiting.

Thirty days in cold darkness stripped weight from his body and left him with a cough that clung like a ghost. When he stumbled back into the barracks, men helped him to his bunk, angry and worried and impressed in equal measure.

A senior officer—one of the respected leaders—told Bill bluntly to stop.

“You’re hurting morale,” the man said. “Every time you get caught, they punish everyone. Every time you risk it, you make things worse.”

Bill listened politely, nodding the way he did when he didn’t want to argue.

Then he started planning again.

Because for Bill Ash, not trying felt like surrender. And surrender felt like collaboration. If the Germans wanted him compliant, they were going to have to kill him to get it.

That was the line in his head.

When the Germans transferred him to Stalag Luft III, they thought they were moving a problem into a tighter cage.

Stalag Luft III was the Luftwaffe’s showcase camp for captured airmen. Built on sandy soil to make tunneling difficult, with barracks elevated, seismograph-like measures, watchtowers, searchlights. The commandant, von Lindeiner, prided himself on order and an “escape-proof” reputation.

He told the prisoners that no one had successfully escaped.

Bill heard that as a challenge.

In Stalag Luft III, Bill found a partner in stubbornness: a fellow pilot named Pat—battle-hardened, experienced, equally obsessed. Together they attempted absurd plans that were half desperation and half brilliance. Once they tried to exploit drainage systems from a shower block—dark, cramped, foul, and nearly impossible. They hid for hours, hoping to slip out under cover of night.

Instead, guards arrived early, tipped off by someone watching too closely.

When guards tore away the cover and light flooded in, Bill and his partner faced a choice: protect the food supply other prisoners had risked to give them, or let it be confiscated.

They ate it.

All of it—dense survival mix meant to last days—cramming it down fast with guards staring. They emerged smeared with chocolate, absurd and defiant, like children caught stealing sweets.

One guard shook his head in disgust. Another laughed.

Bill’s partner laughed too.

Then they went back to solitary.

That was Bill in a sentence: the refusal to lose not just physically, but psychologically. If the Germans wanted him miserable, he’d deny them even that pleasure.

Still, the Stalag Luft III escape committee didn’t want him as part of their biggest project. They were building something massive—multiple tunnels, a coordinated breakout—an operation that required discipline, secrecy, and men who could follow strict orders.

Bill was many things. He was not, by reputation, obedient.

He wasn’t one of the men who would quietly wait for his assigned turn in a line. He was the man who would improvise because waiting felt like death.

So the committee kept him out.

Bill argued. He claimed experience. They didn’t budge.

Instead, he was assigned to a different plan: identity swaps tied to prisoner transfers. If he could move to a new camp, he might escape in an environment where guards didn’t recognize his face.

He traded names with a Canadian pilot scheduled for transfer. The guards checked papers. Faces blurred together when you processed enough prisoners.

Bill boarded the transport train under another man’s identity and watched Stalag Luft III disappear behind him.

At the new camp, he didn’t wait.

Within weeks he was out past the wire with companions, moving through forests and fields with the hungry, tense focus of men trying to become invisible. The plan was ambitious: reach the Baltic coast, steal a boat, try to reach neutral Sweden.

They made progress. They hid. They moved at night. They endured cold and hunger.

Then, near a beach, Bill saw a boat and decided to gamble.

He stood up and called out in English, hoping to find locals who might help.

Men turned toward him.

Gray-green uniforms.

German soldiers—working a field like farmers.

Bill’s heart sank with a familiar mixture of disbelief and bitter humor. He put his hands up again. The soldiers didn’t even look surprised. One of them spoke a little English and asked, with dry amusement, whether Bill really expected German troops to help an escaped prisoner.

Bill admitted he’d hoped they were locals.

The sergeant laughed and said locals would have turned him in faster.

Forty days in solitary followed. Forty days of cold that gnawed at bones, of food so minimal it felt like deliberate slow murder. Bill came out with frostbite on his toes, weight stripped away, skin yellowed with sickness.

Men told him to stop. To rest. To recover.

Bill rested for a week.

Then he began again.

Because a man like Bill didn’t escape only because he wanted freedom. He escaped because it was the only action that made captivity feel temporary. If he stopped trying, the Germans won more than his body. They won his mind.

By spring 1944, Bill’s record was infamous.

Eight escapes attempted. Eight failures. Months in solitary. Guards knew him by sight. Commandants kept thick files on him. He became a walking problem—an American-born Canadian RAF officer with a stubborn smile who treated fences like suggestions.

Other prisoners began calling him “the Texan” as if the label itself explained his insanity.

The Germans developed their own nickname for him, half contempt, half reluctant respect.

Bill did not care what they called him.

Then March 24th, 1944 arrived—two years to the day since his Spitfire crashed in France.

That night, the great breakout happened at Stalag Luft III—dozens of men using a tunnel painstakingly built, a coordinated attempt at freedom so ambitious it almost felt like victory.

Bill was not part of it. He was in solitary confinement again for yet another attempt that had gone wrong.

When he was released and learned what happened, the news hit him like grief disguised as cold air. Seventy-six men had gotten out. Seventy-three were recaptured. Fifty were executed on Hitler’s orders—shot, murdered, made into an example.

Men Bill had known. Men who had shared bunks, shared jokes, shared cigarettes, shared a sense that they were still alive because they refused to surrender psychologically.

Now they were dead.

The camp fell silent in the way only grief could silence hardened soldiers. Escape operations shut down. The risk was too high. The punishment too brutal.

Even Bill understood that.

For about two months, he didn’t plan anything.

He sat in the barracks and stared at walls. He listened to men cough. He watched shadows move. He felt the weight of guilt tug at him—guilt that his constant attempts brought punishment, guilt that he survived when others died.

Then the guilt hardened into something else: determination.

If the Germans could shoot fifty men and still not break the spirit of the camp, then the spirit was worth defending. And Bill defended spirit the only way he knew how.

By refusing to stop.

His later attempts were less grand and more desperate—wire cuts, identity swaps, reckless climbs. Each failure earned more time in solitary. Each release left him thinner, older-looking, more exhausted.

But he never quit.

In a strange way, his stubbornness became its own morale.

When men felt hopeless, they watched Bill crawl out of solitary confinement again, coughing and shivering, and thought: If that man is still trying, maybe the war isn’t over.

He was contagious.

Not like disease. Like defiance.

By April 1945, the world outside the wire was collapsing.

The Soviet army closed in from the east. Allied forces pressed from the west. German guards grew nervous. Some became brutal. Some became careless. The camp’s rigid routines began to fray.

The Germans decided to evacuate Stalag Luft III, force-marching thousands of prisoners west away from the advancing front.

It began in early April. A column of exhausted men trudging through snow and mud, guards shouting, rifles ready. Those who couldn’t keep up risked being left—or worse. The war was ending, but endings could still kill.

Bill, by then, was sick. Jaundice tinted his skin. He could barely walk. His body was more stubbornness than strength. Other prisoners helped him, supporting his weight, because even men who called him reckless understood that leaving him behind was unthinkable.

On the third day of the march, artillery fire crashed nearby—British shells landing close enough to throw dirt and snow into the air. Guards scattered for cover. Prisoners scattered too, dropping into ditches, throwing themselves behind trees.

Bill fell into a ditch and lay there for minutes, heart hammering, lungs burning.

Then he realized something.

No one was watching him.

The guards were focused on survival. The prisoners were scrambling. The column was chaos.

For three years, Bill had tried to escape through fences, through paperwork, through tunnels and drains and disguises.

Now the war itself had opened a door.

Bill climbed out of the ditch and started walking.

Not running—he didn’t have the strength. Just walking. Steady, stubborn, eastward, toward the sound of the guns. Toward the British lines. Toward a future he had been chasing for three years.

He walked through a battlefield littered with the debris of an empire collapsing: burning vehicles, abandoned equipment, German troops retreating with hollow eyes. He kept his hands visible. He kept moving.

At some point he heard voices in English.

A column of British soldiers advancing west.

A young private raised his rifle at the sight of a gaunt figure in ragged clothing emerging from the smoke. An officer shouted, “Don’t shoot—he’s British!”

Bill stopped and raised his hands anyway, because caution was survival.

He tried to speak and heard his own voice crack with exhaustion.

“Actually,” he said, voice raw but still carrying that Texas drawl, “I’m American and Canadian and British.” He paused, then added with a tired grin, “It’s a long story.”

The officer stared at him, then laughed once—disbelieving and relieved.

“You from a POW camp?” the officer asked.

Bill nodded. “Been trying to get out for three years.”

The officer shook his head slowly. “Well,” he said, “you finally made it.”

Bill sat down in the mud.

His hands shook.

Then he started laughing—deep, unstoppable laughter that sounded almost like sobbing. It wasn’t joy exactly. It was release. It was the absurdity of spending three years clawing at wire only to walk out during a barrage because the world finally became chaotic enough to slip through.

He couldn’t stop laughing.

The British soldiers watched him, uncertain, then one of them crouched beside him and offered a cigarette. Bill took it with trembling fingers.

For the first time in years, the air he breathed didn’t belong to the Germans.

Bill Ash was officially liberated on April 12th, 1945.

He was flown back to Britain and spent weeks in a military hospital recovering from malnutrition and exhaustion. Doctors told him he was lucky to be alive. Bill didn’t feel lucky. He felt tired in a way that went beyond muscles.

Tired down to the soul.

In 1946, he stood in Buckingham Palace wearing his RCAF uniform, ribbons neat, shoes polished. King George VI awarded him the MBE for his repeated escape attempts and refusal to cooperate with the enemy.

The ceremony was formal, polite, the kind of ritual that tried to make war seem orderly.

When the King asked how many times he had tried to escape, Bill answered honestly.

“Thirteen times, sir.”

The King raised his eyebrows. “That shows remarkable persistence.”

Bill smiled with that dry, self-deprecating humor he used to blunt the edges of his own legend. “Shows remarkable stupidity too,” he said, “but I appreciate the medal.”

People laughed politely. The King smiled.

But men who had lived behind wire understood. Thirteen attempts wasn’t stupidity. It was defiance as identity.

After the war, Bill faced a problem that had nothing to do with fences.

He had no American citizenship anymore. He had given it up willingly to fight fascism before America entered the war. Canada offered him citizenship, but Bill had fallen in love with Britain—the place that had taken him in, trained him, and, indirectly, built his legend.

Britain granted him citizenship. In 1946 he became British officially.

He enrolled at Oxford—Balliol College—and studied politics, philosophy, and economics. He wasn’t content to let war be the only shaping force in his life. He wanted to understand systems. He wanted to understand ideology. He wanted to understand why humans built cages in the first place.

He graduated with honors. He worked for the BBC as a correspondent. He went to India and watched a new nation wrestle with its future. He became influenced by socialist policies. He became an avowed Marxist—loudly, unapologetically.

It got him fired from the BBC.

Bill didn’t apologize.

He spent the rest of his life writing—books, plays, political essays—leading left-wing groups in England, arguing with the same stubbornness he’d used against German wire. The war hadn’t made him compliant. If anything, it had made him more convinced that systems should be challenged.

In 1963, a movie called The Great Escape came out. It told the story of the March 1944 breakout from Stalag Luft III. Steve McQueen played a character—Virgil Hilts, the “Cooler King”—an American pilot known for repeated escape attempts and constant time in solitary.

People who knew Bill watched McQueen’s character and laughed quietly.

They recognized the shape of him.

Bill always denied it publicly. He pointed out, correctly, that he wasn’t part of that specific breakout. The film was about a particular event, not his entire record.

But everyone who knew him understood the deeper truth: the Cooler King was a composite, and one of its strongest threads was Bill Ash’s refusal to stop.

In 2005, near the end of his life, Bill wrote his autobiography with co-author Brendan Foley. It was called Under the Wire. It became a bestseller in Britain and was largely ignored in America.

Bill didn’t care. He had given up America once and never regretted it.

He died in London on April 26th, 2014.

Ninety-six years old.

He outlived most of his fellow prisoners. He outlived commandants and guards. He outlived the Gestapo officers who threatened him. He outlived the Reich that captured him. He outlived the war that built him.

And when people tried to measure his legacy the way they measured aces—by kill count—Bill’s story refused to fit.

He shot down one enemy aircraft.

One.

He failed twelve escapes and succeeded only when chaos finally made a gap.

Yet his name mattered behind wire because his contribution wasn’t measured in confirmed kills.

It was measured in refusal.

Refusal to accept that captivity was his story.

Refusal to become compliant.

Refusal to let the enemy win by breaking the thing that mattered most: the will to try.

The Germans could lock him in a cell. They could starve him. They could freeze him. They could threaten him. They could punish him until his body looked like it belonged to an old man.

But they could never make him quit.

And that stubborn, reckless, magnificent refusal rippled through the camps like a quiet anthem.

When men felt despair creep in, they watched Bill Ash crawl out of solitary again with a cough and a grin and thought, If that crazy Texan is still trying, maybe I can try too.

That was his real victory.

Not the plane he shot down.

Not the times he got past the wire.

But the idea he embodied: that courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s being afraid and trying anyway. Again and again and again.

Wire is a physical thing.

But surrender is internal.

Bill Ash never surrendered.

And because he didn’t, hundreds of men who should’ve been broken remembered, even in the coldest cells, that the war wasn’t over until you stopped fighting it in your mind.