August 1943, Quebec City. The Château Frontenac rose above the St. Lawrence like a fortress from another century—stone walls, steep roofs, the kind of grand hotel that looked built for diplomats and honeymooners, not for the math of death. Rain had scrubbed the streets clean that morning, leaving everything slick and reflective, and yet inside the war room the air was anything but fresh. It was thick with cigar smoke, tension, and the quiet certainty that somewhere far away men were already dying while the men in this room decided how many more would.

A long mahogany table stretched across the center, polished to a sheen so glossy it caught the pale overhead lamps and bounced their light back in hard rectangles. Across that wood lay reconnaissance photos—black and white, grainy, stamped TOP SECRET in red so bold it looked like a wound. The photos showed a crescent harbor fringed by volcanoes, jungle slopes scarred with roads and revetments, and an impossible density of artillery pits and bunkers tucked into every ridge line like the island had grown teeth.

Rabaul.

Even before anyone spoke, every officer in the room understood what those photographs meant. This wasn’t a target; it was a trap. Airstrips cut into volcanic rock. Concrete bunkers. Camouflaged pillboxes. Coastal guns aimed like accusing fingers toward the sea. Ships docked in the deep water harbor, sheltered by the natural walls of the land and the manmade armor of the Imperial Navy’s obsession.

Franklin D. Roosevelt sat forward in his wheelchair, expression unreadable. He didn’t need a briefing to understand the message the photos delivered. A man could look at Rabaul and see the future—rows of landing craft burning in surf, Marines pinned on beaches, bodies piled where the tide could not wash them away. Another Tarawa. Another meat grinder. Another place that would be remembered in America by the names carved on headstones.

Somebody’s watch ticked too loudly. Paper rustled like a small animal trying to escape.

General George C. Marshall broke the silence first, voice calm in the way surgeons sound when they point to the knife. “We’ll need two corps minimum if we take it head-on. The casualty estimates…” He paused, as if even saying the number aloud would summon it. “They’re unacceptable.”

Admiral William Leahy leaned back, cigar glowing faintly. “You’re talking about fighting into a volcano lined with concrete and machine guns,” he said, and there was no drama in it—only blunt recognition. “You don’t ‘capture’ a place like that. You pay for it.”

Another map slid onto the table then, not a reconnaissance photo but a clean operational chart with neat lines and arrows. It didn’t go through Rabaul.

It went around it.

The red line traced an arc—Bougainville, the Admiralties, Cape Gloucester—touching the outer edges of the Japanese perimeter like a hand circling a wasp nest without ever closing into a fist.

The idea hanging in the air was so strange it felt wrong. In every war room in history, the instinct was the same: you destroy enemy strongholds. You don’t leave them behind you. You don’t let a fortress sit at your flank, watching you pass.

A voice—steady, confident, as if describing weather—put the unspoken into words.

“We don’t take the fortress,” MacArthur said. “We starve it.”

For a heartbeat the room didn’t react because minds needed time to catch up. Then faces shifted. Brows lifted. Even men who had seen the impossible in war looked unsettled.

Admiral Halsey—who normally had no trouble filling any silence with opinion—stopped short, lips parting as if the words had to be inspected before they were allowed out. “General,” he said finally, careful now, “you’re suggesting we leave the strongest Japanese base in the Pacific untouched.”

MacArthur didn’t flinch. “No, Admiral. I’m suggesting we turn it into their tomb.”

The sentence landed heavy. Not because it was cruel—war had already stripped everyone in that room of the luxury of delicate language—but because it was new. It was a strategy that didn’t look like the wars they’d studied. It flew in the face of West Point and Annapolis doctrine. Strongholds were meant to be smashed, captured, raised on poles as proof of dominance.

This was something else.

A siege without walls. A chokehold without a battlefield.

Roosevelt looked down at the map again, his gaze settling on the dotted ring that encircled Rabaul without touching it. His face didn’t show triumph or dread. It showed calculation.

“Expected resistance on Bougainville?” he asked.

“Manageable,” came the reply. “Garrisons, yes. Not this.”

Roosevelt’s hand hovered near the operational orders. Outside the windows, the St. Lawrence River shimmered like a silver blade, cutting through Quebec. Inside, the silence turned almost sacred. Because everyone understood what this decision meant, even if no one said it aloud.

Bypassing Rabaul wasn’t just tactical. It was human.

It meant leaving one hundred thousand enemy soldiers trapped on a volcanic island with no way out. It meant months—maybe years—of hunger, disease, and slow psychological collapse under the steady rhythm of bombs and the creeping certainty of abandonment. But it also meant not sending tens of thousands of young Americans into a fortress designed to turn courage into casualty lists.

Roosevelt picked up his pen.

The scratch of ink on paper was quiet, almost delicate. But the moment it happened, the room changed. That signature didn’t just authorize an operation. It tilted the war.

Operation Cartwheel had begun.

The next morning rain swept across Quebec like a gray curtain, but inside the conference halls the air still carried the shock of what had been approved. Not everyone was comfortable with it. There were men who had built careers on the idea that you never leave a threat behind you. There were officers whose instincts screamed that bypassing Rabaul was tempting fate, that the Japanese would strike out from their fortress the moment the Allies turned away.

And yet the new war—this war of airfields and logistics—didn’t obey old instincts. It obeyed reach, fuel, tonnage, runway length, radio range. It obeyed who could move supplies and who could stop supplies from moving. It obeyed maps more than it obeyed flags.

Ten thousand miles away, Rabaul stood defiant on the northeastern edge of New Britain, carved into volcanic ridges like a monstrous scar. From the air, Simpson Harbor almost looked peaceful—blue water cupped by green hills. But beneath that surface lay two years of backbreaking labor and engineering obsession. Five operational airfields. Reinforced shelters thick enough to swallow bombs and survive. Coastal guns stacked along the shoreline. Tunnel networks drilled into rock so deep they felt like a second world.

The Imperial Navy called it the Gibraltar of the Pacific.

Japanese officers stationed there believed it, too. To them, Rabaul wasn’t merely a base—it was destiny. A symbol of Japan’s dominance in the South Pacific. A place built not to be taken, but to be feared.

While they poured more concrete and laid more wire, they imagined the invasion coming like a storm. They pictured American ships on the horizon, landing craft grinding forward, the waves turning red. They rehearsed that future with the confidence of men who believed a fortress could bend fate.

They didn’t know that far away, in rooms filled with smoke and maps, someone had decided the invasion would never come.

In Brisbane, Allied headquarters began assembling a different kind of attack. Intelligence officers pinned aerial photos on boards and circled gun emplacements hidden beneath jungle camouflage. They tracked radar stations on ridgelines. They counted aircraft revetments, fuel dumps, shipping berths. They measured Rabaul not as something to conquer, but as something to contain.

The old guard muttered. “Madness,” some said. “You don’t leave a beast like that alive.”

But the airmen and the logisticians had a colder view. A fortress, they argued, was only powerful if it could reach. If it could send planes, ships, supplies. If you could cut those arteries, the fortress could sit there bristling forever and still be nothing but a cage.

So convoys began to move—not loaded with invasion ladders and beach gear, but with bulldozers, runway steel matting, cement, aviation fuel. These weren’t the tools of assault. They were the tools of a noose.

Seabees and engineers landed on islands that didn’t look like much on a map—just green bumps in endless water—and turned them into airfields. They worked under rain that came sideways, under heat that made men faint, under the constant fear of ambush. They flattened jungle with machines and muscle. They laid down runways like strips of authority. Every new airstrip pulled the ring tighter. Every mile of runway extended the reach of bombers and fighters. Every base carved into jungle was another finger closing around Rabaul’s throat.

On Bougainville, men dug and built and sweated until their uniforms turned the same color as the mud. They worked while artillery thumped in the distance. They worked while mosquitoes swarmed like smoke. They worked because they were building something the enemy couldn’t easily destroy: proximity.

And above it all, aircraft began to prowl.

Japanese officers inside Rabaul started noticing the change first as a nuisance. Recon planes circling more often. Shadows crossing the harbor. A distant engine note that lingered longer than usual. They reported it. Logged it. Cursed it. But their minds framed everything through the expectation of invasion. More reconnaissance meant the Americans were preparing to hit the beaches.

They couldn’t imagine a war where the beach never mattered.

By mid-October 1943, the first hammer blows fell.

American bombers broke through cloud cover over Rabaul and came in low and fast, formation tight, engines roaring like an oncoming storm. B-25 Mitchells. P-38 Lightnings slicing the air with predatory grace. B-24 Liberators higher up, steady and relentless.

From the Japanese command bunker beneath volcanic ridges, General Hitoshi Imamura adjusted his field glasses and watched smoke rise from Tobera airfield. His men fired anti-aircraft guns until the sky bloomed with angry black bursts, but the attackers kept coming—not once, but again and again, like the sea returning to a shore it intended to claim.

Within seventy-two hours, dozens of Japanese aircraft were destroyed, many of them on the ground, parked too close together, caught before pilots could scramble. The fortress had been built to withstand naval bombardment and invasion assaults. But no one had prepared for a siege delivered from altitude, repeated daily, and measured in wear rather than conquest.

The bombers didn’t stay to admire their work. They struck, turned, vanished back toward their island bases. And then they came again.

Imamura’s frustration hardened into something colder. He had built defenses for a fight that was not arriving. And yet he was being attacked as if he were already defeated.

Outside the bomb craters and smoke, Rabaul still looked alive. Ships moved under camouflage netting. Gun crews drilled. Orders were barked. But cracks were forming where no concrete could reach: in supply lines, in fuel calculations, in stomachs.

MacArthur’s staff ran the numbers with the unemotional precision of accountants. A garrison of that size didn’t just need bullets. It needed food, medicine, fuel, spare parts, morale. Thousands of tons of supplies. Every day.

And the Americans were now controlling the sea and sky around those supply routes like hands closing on a valve.

Japanese ships that tried to run the blockade started dying in pieces. A destroyer pushing south with aircraft engines and medical supplies took bombs before it could reach safety and went down with men who never saw the enemy’s faces. Cargo vessels loaded with rice and canned fish were strafed until they capsized in flames. Every attempt to bring life into Rabaul ended in fire on the water.

Inside the fortress, the pattern became impossible to ignore.

The Americans weren’t trying to break in.

They were sealing it shut.

At first, ration cuts were small enough to disguise. A little less rice. Vegetables stretching thinner. Officers telling men to tighten belts and remember discipline. The Imperial Army had endured hardship before. Hardship was part of its mythology. Hardship was supposed to forge honor.

But hunger isn’t impressed by mythology.

November dragged on, and half rations became routine. Fresh vegetables disappeared. Medical supplies dwindled until doctors reused bandages and operated without anesthesia, teeth clenched, hands steady, prayers swallowed. Men who had trained for glory began to look at their own hands and see bones pushing forward under skin.

Discipline held, because discipline was what they had. But morale began to rot.

Some tried to flee. It sounds absurd now—where would you go, in open ocean, hundreds of miles from any safe shore? But desperation makes men gamble on impossible odds. A few were caught building rafts from oil drums and parachute canvas. Others simply vanished into jungle trails and were never seen again. The sea took some. The jungle took others. Rabaul took the rest.

And still the fortress fought—at least in appearance.

Imamura had no orders to surrender and no inclination to do so. He turned inward. Engineers reinforced bunkers with salvage steel. Coastal crews drilled at night to avoid detection. Fighters were grounded to conserve fuel, saved only for reconnaissance or last-ditch interception. The fortress shifted from outward aggression to inward endurance. It stopped thinking like a spear and started thinking like a shelter.

But the Americans kept coming, and the rhythm became cruelly predictable.

Morning raids. Afternoon strikes. Night patrols hunting ships. Bombs like metronomes. Pressure without pause.

Not a single American rifle landed on New Britain.

That was the part that began to break men in ways hunger could not. Because hunger you could frame as sacrifice. Hunger could be endured if you believed relief was coming, if you believed the suffering bought something—time, victory, honor.

But what did you call suffering that bought nothing?

From above, American reconnaissance flights started seeing strange sights. Gardens carved into bomb craters—rows of green where explosions had bitten the earth. Chickens raised inside former aircraft hangars. Soldiers digging vegetable trenches beside machine gun nests. The fortress was becoming a subsistence colony, a military graveyard where the dead hadn’t yet fallen.

American pilots, young men strapped into steel with thousands of pounds of explosives beneath them, began writing odd things in their logbooks. Not about dogfights—there were fewer and fewer of those. Not about flak—there was less of that too. They wrote about stillness.

One crewman scrawled in a journal: Feels like we’re bombing ghosts.

At Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nimitz glanced at an intelligence chart covered in red pins. One pin on New Britain hadn’t moved in months. He tapped it, dry as ever. “That one isn’t a threat anymore. It’s a warehouse full of uniforms and bones.”

And that was the strangest part: Rabaul was still enormous, still armed, still bristling with guns and tunnels and concrete. But relevance had drained out of it like blood from a wound.

The war moved on.

American forces leapfrogged forward—toward the Philippines, toward the next stepping stone, always leaving behind islands that were still technically “enemy” but strategically dead. Rabaul sat there like a clenched fist that couldn’t reach anyone.

Inside the command tunnels, Imamura paced as his world shrank. Weekly reports became lists of absence: fuel nearly gone, ammunition down, medicine nonexistent, food stores measured in days rather than months. The fortress that once consumed thousands of tons a day was now starving on scavenged rice and boiled rainwater.

The psychological damage deepened.

Men trained for heroic death now lived like trapped animals. No mail. No victories. No movement. Just the daily reminder from the sky that they were seen, monitored, punished. Leaflets drifted down like ash—messages in crude Japanese: You have been abandoned. Japan cannot reach you. Surrender and live.

Some burned the leaflets immediately. Others hid them in helmets, tucked into shirts, kept like secret evidence of a reality they weren’t allowed to speak.

A sergeant attempted to cross the harbor on a door panel, clinging to wood like a child. He didn’t make it. His body washed up days later, and in his waterlogged hand was a scrap of paper with words written in charcoal: I miss the sky.

By April 1944, fuel was so scarce that aircraft sat intact but useless. Engines dry. Tires rotting. Imamura rationed aviation gasoline like morphine, reserving it for emergencies that never arrived. Mechanics scavenged scrap metal to forge tools. Units stripped aircraft for parts. One fighter’s aluminum skin became roof plates for a sick ward. Another was buried simply to keep rats from nesting in fuel tanks.

When you run out of purpose, you begin repurposing everything.

Typhoons came. Monsoons flooded tunnel systems. Corridors collapsed. Latrines overflowed. Gardens drowned. Disease followed—malaria, dysentery, cholera moving through weakened bodies like fire through dry grass. With no medicine, sickness became its own siege, an enemy the fortress could not shoot.

Reports of mental collapse started appearing among officers—things whispered late at night, shameful and real. A major speaking softly to a tree as if it were his wife. A communications man standing in surf, motionless, staring into open sea, as if waiting for the ocean to give him orders. Men who had once been steel now unraveling thread by thread.

Imamura responded the only way he knew how: with discipline. With silence. With routine.

He ordered readiness drills for landings that would never come. Soldiers practiced bayonet charges on empty jungle paths with boots that had rotted and rifles that had no ammunition. Coastal batteries cleaned barrels they would never fire again. One anti-aircraft gun was disassembled—not in surrender, but because they needed the metal for cooking pots.

They weren’t defending a place anymore.

They were defending an idea: that they had not been forgotten.

But by late 1944, even Tokyo’s messages came less frequently, and when they came they were thin and ritualistic. Hold your position. Serve until called home. It sounded like faith, but it felt like abandonment.

Above Rabaul, American raids shifted from tactical to psychological. Bombs dropped on movement, on smoke from cook fires, on anything that suggested life. Not because Rabaul had to be destroyed—it had already been neutralized—but because the Americans understood something brutal: the most effective weapon now was the reminder.

We see you. Every day. And we still don’t need to come.

One B-24 pilot wrote after a July 4th raid that dropped hundreds of tons of explosives on an airfield that no longer launched planes: Rabaul doesn’t fight back anymore. It just takes it.

War stripped of glory looks like that. Not charging beaches. Not flags. Just mechanical attrition, routine violence delivered on schedule.

By early 1945, the fortress resembled a skeleton wrapped in steel. Recon photos showed rusted fuel drums overgrown with vines, trenches filled with stagnant rainwater, airfields being swallowed by jungle. Nature reclaiming ambition. The soldiers inside weren’t dead yet, but they were becoming something else—ghosts living in a place that history had already passed by.

And still Imamura refused to yield. His duty burned stubbornly, not because he believed victory was possible, but because duty was the only remaining structure that could hold men together in a world that had turned to hunger and silence.

Then, in August 1945, the world cracked open.

On August 6th, a single bomb erased Hiroshima.

Word reached Rabaul through broken channels, like sound traveling through water. Not an explosion they could see, but a message that carried its own shockwave: Japan was preparing to surrender.

Imamura received the communiqué through neutral channels. In his underground bunker, he read it in silence. No outburst. No grand speech. An aide watched him trace the kanji with a trembling finger as if confirming they were real. Then Imamura folded the paper and tucked it into his uniform pocket, like a man placing a funeral notice close to his heart.

Outside, soldiers still dug ditches and repaired collapsed bunkers and scraped mold off medical stations, not because it mattered, but because they had forgotten how to stop. Routine had become a survival mechanism. Motion had become a prayer.

When the official surrender came weeks later, it didn’t feel like defeat in the dramatic sense. It felt like gravity returning after a long absence. Many men wept—not with grief, but with the hollow shock of realizing no one was coming to fight them, no one was coming to honor them, no one was coming to validate the suffering. They had been left behind not by enemy force, but by enemy choice.

For soldiers trained to die with honor, being bypassed was the deepest humiliation.

On September 6th, 1945, in a dim command bunker lit by oil lamps and thin sunlight filtering through cracks in concrete, General Hitoshi Imamura met Colonel Harold Regleman, representing MacArthur. There was no grand ceremony. No cheering troops. No band. Just two men in uniforms that carried the weight of empires.

Imamura removed his katana slowly. The gesture was careful, almost ritualistic, as if he were unspooling the last thread of something ancient. He handed it over without a word. Then he bowed.

In that moment, the siege ended—not with a battle, but with a handoff.

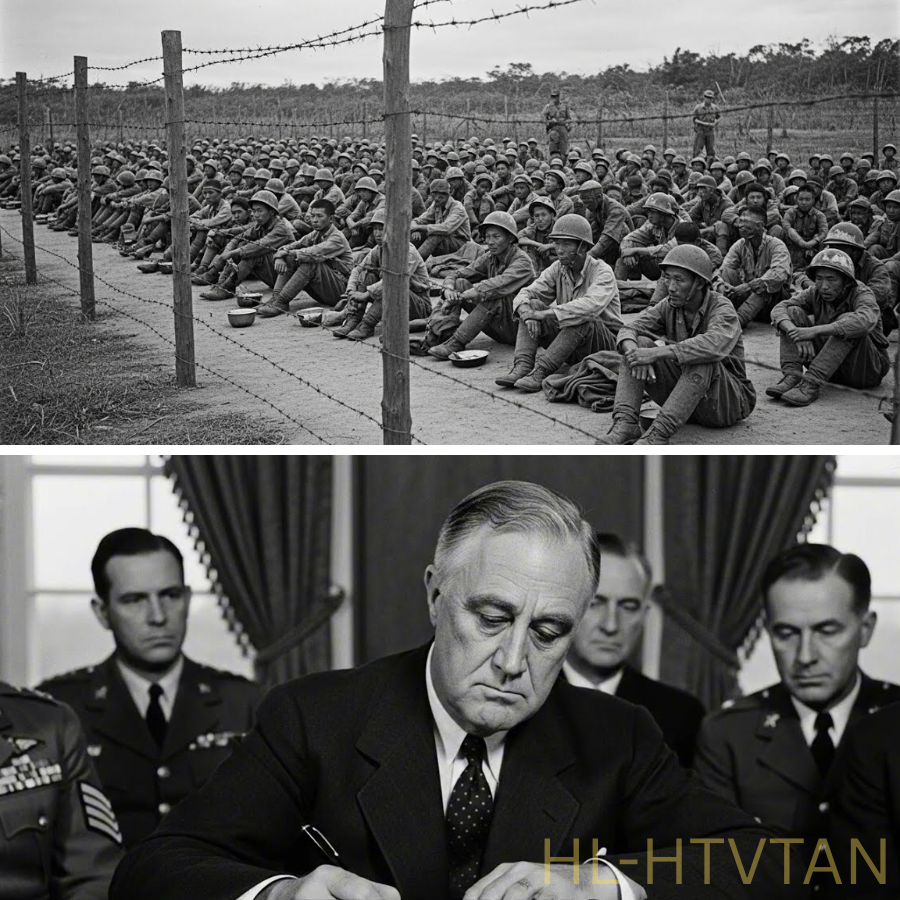

The Americans had braced for fanatic resistance, expecting a garrison that would fight to the last breath. What they found shocked them: men weighing ninety pounds, bodies wasted by disease, eyes sunk deep into faces that looked too old even for war. Hospital units with no anesthetics. Bandages reused until they were more stain than cloth. Men who had lived underground for months like cave-dwellers, emerging only to farm craters and collect rainwater.

And yet even then, the discipline was eerie. Not a single Japanese soldier had broken rank in the final surrender. They lined up, silent, hollow, like a force preserved by stubbornness rather than strength.

Colonel Regleman toured the fortifications afterward—six-foot-thick bunkers, anti-aircraft batteries aimed at skies that had already won, interlocking fields of fire that had never fired a shot in defense against a landing. He walked through tunnels built for a battle that never came. He saw the fortress as it had been intended: a place designed to kill thousands of Americans on beaches.

And he understood, with a chill that had nothing to do with weather, what bypassing had prevented.

Had the Allies invaded, Rabaul would have been Saipan and Peleliu and Iwo Jima stitched together into one long scream. Instead, it had been reduced by starvation, isolation, patience. Not blood on beaches, but time doing the killing.

A GI wrote home afterward, stunned by what he’d seen: We didn’t fight them. We didn’t bomb them to death. We just let time do it.

That was the strange, modern horror of Operation Cartwheel. It proved you didn’t have to storm a fortress to destroy it. You only had to isolate it, outlast it, and let its strength become its burden.

Rabaul—the mightiest Japanese base in the Pacific—had been neutralized without a single Allied boot landing in its heart. Not conquered in the way old wars conquered, but rendered irrelevant, starved into silence, turned from a weapon into a prison.

In the end, it didn’t fall with a roar.

It faded.

And when it finally surrendered, it did so not because it had been beaten in battle, but because the war had ended elsewhere—leaving behind a tomb-sized fortress full of men who had spent two years waiting to die in a war that had moved on without them.